Abstract

In this chapter we use rich longitudinal data to examine the typical growth of vocabulary in children as they age from 4 years onwards. Vocabulary is a robust indicator of language development and of early cognitive growth. The data demonstrate the surprising variability among children of similar ages in their early cognitive growth. This variability leads to difficulties in predicting early vulnerability and in subsequently selecting children for targeted interventions. By examining the developmental circumstances that accelerate or retard changes in the growth of this aspect of language development we assess the implications of the findings for the subsequent population reach and actual participation of children in programs designed to reach those who are variously vulnerable.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

At the outset of the twenty-first century, Australian social and economic circumstances have prompted a relentlessly increasing demand for, and supply of, a range of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) services as parents—particularly women—have moved into the labour force to support their family needs and protect their own futures. This demand has produced a decade of volatility in the number, design, and provision of ECEC services that seek to improve the development of infants and children. The distribution, cost and regulation of the standards and quality of ECEC services have been the subject of intense debate and scrutiny. Along with these developments, and because of the demand for such services at ever-earlier points in child development, there has been a rising focus upon the instrumental role that early years opportunities play in establishing and advancing developmental capacities important for onward learning achievement—particularly those that concern cognition and social skills.

Accompanying all of this has been a burgeoning scientific evidence base linking early infant and childcare programs, and the nature of the opportunities and expectations that they provide, to the subsequent capabilities of children to achieve more optimal outcomes in education and onward into adult life. Consistent with a life course approach, early infant and childhood programs, typically in the epoch from birth to the commencement of formal schooling, have been identified as one of the key mechanisms to break the intergenerational cycle of deep and persistent disadvantage, and to reduce inequalities in educational outcomes across socio-economic groups (Heckman, 2006). For example, foundational research such as the Perry/High Scope and Abecedarian studies has demonstrated the long-term benefits of early childhood education programs for children from disadvantaged backgrounds (Campbell et al., 2012; Schweinhart, 2013). Such findings have prompted great enthusiasm among the Early Years sector.

And yet, amid the impressive array of scientific evidence about the positive impact and role of early experiences on subsequent neurobiological (Shonkoff, 2016), cognitive (Heckman, 2006) and non-cognitive maturation (Gutman & Schoon, 2014; Niles et al., 2006) in typically and atypically developing children, the science on the delivery of programs that actually change the level and rate of development and growth in infants and young children is far more sobering. In their meta-analysis of 84 carefully controlled experiments (i.e., “trials”) of early infant and child interventions that met minimum scientific standards spanning the period from 1955 to 2010, Duncan and Magnuson (2013) confirmed that such programs were indeed efficacious across a range of outcomes. However, the authors were explicit in noting that the average weighted effect size across all programs was small (0.21, measured in standard deviation units). Duncan and Magnuson also noted that programs designed by researchers imparted larger effects (0.39) than did programs designed by non-researchers (0.18) and that programs before 1980 produced significantly larger effect sizes (0.33) than did those that began after 1980 (0.16). This decline of program effect sizes over time likely reflects the fact that children in the control groups were increasingly being exposed to some centre-based care and were also benefiting from improved home environments (notably increases in maternal education) relative to those children in the control groups of earlier epochs.

In Australia, the ECEC sector provides a range of child care and preschool services. Families partake of ECEC via a mixture of informal care (grandparents, other relatives, friends, neighbours or nannies) and formal care (provided predominantly through long day care and outside-school-hours care) and preschool programs which are structured play-based learning programs delivered by early childhood teachers. The proportions of these types of care exhibit age-dependent variations: Typically, prior to the age of 1 year, parents use more informal care while from ages beyond 1 year increasing amounts of formal care are used (Baxter 2015; Baxter & Hand, 2013). Children may be exposed, at any age, to both informal and formal care. In 2014, among children aged 0–4 years, 22% used formal care only, 18% used informal care only, 12% used both types of care with the remaining 45% of children not attending child care (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2014). Long day care was the main source of formal ECEC to children under school age, with its use peaking at age 2–3 years although it is notable that about 30% of 1-year-olds and 4-year-olds were also in long day care (Baxter, 2015).

Not all families use ECEC and where they do, there are striking differences in the mix and use of ECEC by families that have differing structures and capabilities. For example, single parent families are early and heavy users of formal care: Where single parents are employed, 65% of their 0–2 year-old children are in formal ECEC (Baxter, 2015). This contrasts to 49% of children in couple families where both parents are employed. These proportions drop to 23% where a sole parent is not employed and to about 14% where one of the parents is not employed in a couple family. From the age of 3 years onwards the use of ECEC by parents markedly interacts with offers of, and expectations about, enrolment in education in the period before children are expected to commence full-time in Year 1. In dual employed families, 32% of children were in preschool, while the percentage was lower (23%) in families of employed single parents. In combination, the variation in effect sizes between different services and the different rates of enrolment of children in ECEC by families with differing structures and capabilities, is seen to either deepen existing, or impart onward developmental inequalities in outcomes among specific groups of children. These inequalities extend also to the quality of ECEC received by some children in relation to others.

ECEC classrooms within the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) areas have been found to have lower levels of instructional support provided to children than those in the highest SES areas (Tayler, 2016). Such differences accumulated across pre-kinder and kinder programs (approx. commencing ages 4–5 years) and led to children being approximately 3.3–4.9 months behind their peers in more advantaged neighbourhoods (on measures of verbal ability). These differences in the quality of, and child growth responses to, early childhood programs, suggest that the pragmatic considerations of how well such opportunities are arranged and resourced to deliver developmental advantage to children is of substantive importance. The enthusiasm for these opportunities is evident by their growing promotion and use. The promise of improved life chances for children who participate in them has enormous popular appeal and is policy relevant in societal settings that seek more equal outcomes for all children. These programs are designed with the intent to change the level and rate of developmental growth in participating children. However, the empirical data on the actual starting levels and onward rates of developmental growth of children are strikingly absent in contemporary research findings. What is available suggests caution in enthusiasm for the size of growth effects imparted to children by such programs, the uniformity of these effects across different groups of children and the need for greater precision, reach, and proportionality in the delivery of these programs.

With these observations as our motive, we add to the literature on the delivery of early years opportunities by describing typical growth patterns in very young children. We go on to estimate the extent to which developmental circumstances accelerate or retard changes in early cognitive growth and later literacy and numeracy. Finally, we assess the implications of these findings on the subsequent population reach and actual participation of children in these programs particularly regarding the very groups often in the target range for program benefit.

Measuring the Developmental Growth of Children Is Not Easy

The defining feature of infancy and childhood is growth, and longitudinal studies are a mainstay for evidence about growth in early life. Yet, many contemporary longitudinal studies are extremely challenged to meet the requirements of consistent, repeated measurement of growth characteristics that permit appropriate growth modelling (Zubrick, 2016). Moreover, growth phenomena are not easy to capture during periods when children are rapidly changing.

Some measures, such as weight, height, girth, head circumference, muscle mass and strength lend themselves more easily to repeated measures with the same metrics over long periods of time. Other growth characteristics are considerably harder to repeatedly measure—some cognitive abilities including reading and numeracy, and time-based activity measures appear in longitudinal studies and may do so with enough consistent repetition to allow growth modelling. In contrast though, growth of subjective decision making, risk aversion, emotional regulation and introspection are examples of important developmental characteristics for which growth measures are either absent or studies using them over time, lacking.

In this chapter we use early childhood growth in receptive vocabulary to observe important aspects of growth and its variability and to characterise patterns and circumstances of this growth relevant to the design and implementation of developmental opportunities in the early years. Vocabulary is a robust indicator of development across the lifespan (Powell & Diamond, 2012; Vasilyeva & Waterfall, 2011). Comprising the words we understand, receptive vocabulary can be measured from about 8 months of life onwards and thereafter throughout life. Vocabulary growth is rapid, expanding from infancy to about 200 words at age two to 20,000 words at age 8 (Anglin et al., 1993; Fenson et al., 2007). The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) is one such measure that is well-standardised and can be used repeatedly across the life course (Dunn et al., 1997). Unless otherwise noted, it is used as the principal measure throughout this chapter.

In the findings we present here, we model the growth of vocabulary from variables principally collected in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) (Taylor et al., 2011). The generalisations we derive from these findings describe modelled data. These models are best thought of as heuristic, or exploratory, devices to illustrate general principles. Where there are significant limitations to our generalisations arising from these models, we describe these.

Risks That Predict Low Language Performance Are Weak

There is an extensive literature on the selection and modelling of risks and their association with child development outcomes with cumulative risk models being frequently constructed (Evans et al., 2013). A range of risks is examined using statistical techniques to permit them to be added together to calculate a cumulative total. Despite their advantage, and simplicity of interpretation, cumulative risk models are limited in their capacity to capture aspects of duration and timing, nor do they provide insight into underlying, and perhaps more universal, mechanisms that link adversities to outcomes of interest (McLaughlin & Sheridan, 2016). In addition to this, developmental risks not only have the propensity to cluster or aggregate over time as well as spatially, but individuals within the same gender, ethnic category or social class are likely to share common constellations of risks (Kagan, 2018). These constellations, as we will show, impart differing rates of growth.

Language development is truly one of the endowments unique to human beings and so clearly manifest through the interplay of the child’s endowments with their environmental circumstances. The clear growth of language would suggest a virtually unimpeded, steady, and “rocket” like trajectory upwards. And yet, systematic studies of language growth return a picture of surprising variability within and between children in the growth of their vocabulary specifically and language more generally. The initial onset of language development is principally dominated by factors internal to the child (Zubrick et al., 2007) and most children who start late, subsequently catch up (Reilly et al., 2010). This has significant implications for those interested in early intervention strategies that seek to promote child development as well as early identification of children for specific treatment.

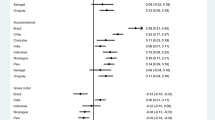

Table 3.1 shows risks associated with lower language ability at the age of 4 years. A total of 28 candidate predictors was selected from the LSAC data based on empirical evidence. Sixteen of these variables were individually associated with vocabulary growth differences of at least 6 months over a six-year period (Christensen et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2013). In the multivariable modelling, ten of these variables were associated with lower vocabulary growth.

This growth modelling of individual risks also showed that a large set of well-selected and measured predictors explained very little of the variation in children’s language growth from 4 to 8 years of age. For most risk variables, adjusted effect sizes were negligible to small. The total amount of variance in vocabulary growth that the risk variables account for was an additional 7% after adjusting for advancing age, which accounted for another 52% of the variance in vocabulary development. This 7% is a surprisingly small percentage of increase in variance accounted for by the risk variables over and above that accounted for by the child merely getting older.

Predicting the Children Who Will Need Help Will Miss Many Children

The findings here are important because they signal a critical feature about child development: It is characterised by large variability within children and between them. The findings show that age is the biggest explanatory source of variation related to vocabulary growth. Closer scrutiny of the children’s growth reveals additional insights. First, when age is appropriately accounted for, vocabulary growth varies by where children start their growth (Fig. 3.1, upper). Those in the bottom 15th percentile at age 4 display more rapid growth relative to children whose starting positions are higher. Second, when these individual children are observed over this same period they display striking positional movement (Fig. 3.1, lower). Some children progress to higher levels of vocabulary performance but some also display declines in their performance.

What does this mean when we try to predict who needs help? Our predictive models reveal that we are very good at predicting those children who will not have low receptive vocabulary status at age 8. Of the children we predicted at age 4 to not have low receptive vocabulary at age 8, we will have only misclassified 5.9% of these who actually go on to have low receptive vocabulary at age 8. This might be deemed a tolerable level of predictive error.

However, we are typically interested in predicting those children who are likely to be developmentally challenged—after all, it is these children we would like to offer programs to improve their early developmental skills. Unfortunately, for the children at age 4 who were predicted to go on to have low receptive vocabulary at age 8, 74.2% of these children actually go on to be classified as not having low receptive vocabulary at age 8. In other words, it is possible that considerable resources will be deployed towards children who, in all likelihood, would not need intervention. Decisions would need to be made as to whether this represents a tolerable use of resources for monitoring and/or intervention to assist the 25.8% of children classified at age 4 who would otherwise have a low receptive vocabulary status at age 8. In summary, our findings exhibit low predictive utility (Christensen et al., 2014).

Early child development is certainly characterised by growth—and some of it, quite rapid. But our findings and those of others demonstrate that development is also highly variable and characterised by children moving up and down in their skill levels. These features align with the observation that most early development interventions are characterised by small effect sizes. After all, interventions are designed based on assuming or predicting which children will benefit (or not) from early interventions by using predictors identical or similar to the variables in our models. These interventions are “pushing into” growth characteristics of the children that are in and of themselves highly variable. This variability would contribute to weaker effect sizes.

It would be easy to adopt a gloomy view about the benefits and use of early developmental programs based on observations like these. Instead, our view here is to posit that high variability is a basic feature of early child development and that it invites a broader understanding of how policies, funding and practices might be arranged to influence better outcomes for all children. We turn to this in the following sections.

Moving from Individual Risks to Describing Developmental Circumstances

The variability in children’s vocabulary growth from ages 4 to 8 makes an important transition to reading literacy at age 10 years. This permits an extension of the period over which to observe stability and change in growth characteristics (Fig. 3.2) from age 4 to age 10 (Zubrick et al., 2015).

Positional movement in language at ages 4, 6, 8 to literacy at age 10. (From Zubrick et al., 2015, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0135612.g002. Source: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children)

The measures in this model have been standardised to capture children performing at or below the 15 percentile in vocabulary (ages 4–8) and reading (age 10). The children above the 15th percentile are classified as having middle to high performances. In this series of observations on the same children, there are 24 or 16 possible combinations of movement in and out of “low” to “middle-high” levels of performance. With this, it becomes possible to focus on patterns of stability and change as early development progresses. Children can remain stable (i.e., in the same performance category) or they can change category as they develop.

When studied this way, the most prevalent developmental pattern was for children to start in the middle-high category and remain so—69% of the children studied were performing in the middle-high group throughout the 6-year period of observation. We refer to this pattern as “Developmentally Enabled”.

One of the least common developmental patterns was the stable low pattern: Only 1% of children were persistently low at all age points. There are, of course, intermediate pathways in which there is change in developmental status which results in improving patterns (8%), declining patterns (10%), and fluctuating patterns (12%) of development. These findings highlight that children move in and out of developmental vulnerability and that the patterns observed here continue to point towards high levels of variability in developmental status through these early years.

Can the sixteen individual exposures to risk for developmental vulnerability that we display in Table 3.1 be used instead to describe clusters or classes of risk circumstances that would better characterise developmental growth, its variability, and how interventions might be considered? While risks to development undoubtedly accumulate the pattern of their association, this does not suggest simple additivity. Different risks accumulate for different children.

The average number of risk exposures at the age of 4 for any one child was about 2.5 risks. 14% of children were exposed to none of the designated risk factors, almost two thirds of children had two or more risk exposures, with 42% of children experiencing three or more risks. These sixteen possible risk factors allowed for 216 (65,536) possible combinations of risk factors. But of these, 1585 combinations were observed in the data.

Figure 3.3 displays a “heat map” of the dichotomised individual risks from Table 3.1 that are associated with low vocabulary growth. This figure shows how some risks cluster together more strongly than others. We used a statistical technique to identify substantively meaningful clusters or “classes” of risks within which participants have a similar response pattern (Christensen et al., 2017). The results of the latent class analysis distinguished six different groups of risks—or, developmental circumstances—that children experience. These circumstances are not mutually exclusive. Our statistical approach instead estimated the probability of children belonging more to one group over another and we assigned children to the group for which they had the largest estimated probability.

The clustering of risks for low language development at age 4. (See Christensen et al., 2017. Source: Longitudinal Study of Australian Children)

The first developmental circumstance (i.e., the reference group) we described as Developmentally Enabled. This group made up 46% of the sample. On average, each child in this group was exposed to only 1.0 risk at age four. The distinguishing feature of children who were Developmentally Enabled was consistently lower than population average proportion for each of the risk factors, with a likelihood of zero risk for teenage motherhood, being in families with four or more siblings, and the study child not being read to at all.

The next developmental circumstance comprised Working Poor (20%) families. On average, each child in this group was exposed to 2.8 risks. Relative to the overall population proportion, this group had a similar proportion of mothers who were unemployed (44%) when the child was 4 years old. But, children in this group were more likely to exhibit low school readiness, have mothers with low education, have four or more siblings, and live in disadvantaged areas. Non-English speaking status families were not in this group.

The third circumstance, which we termed Overwhelmed (10%) was typified by multiple risk factors across all domains. On average, each child in this group was exposed to 6.1 risks. Relative to both the Developmentally Enabled and the population average, this group had an increased likelihood of all risk factors, other than maternal non-English speaking background.

The fourth circumstance was characterised by a combination of factors that were unique to the individual child and which we termed Developmental Delay (9%). On average, each child in this group was exposed to 3.8 risks. Higher proportions of children in this group had low temperamental persistence (47%) and reactive temperament (40%).

Making up 8% of the sample, the fifth circumstance was typified by Low Human Capital and can be contrasted to those in the Developmentally Delayed circumstance because of the higher proportion of teenage mothers (9%) and maternal low education (53%) in this group. Maternal unemployment (65%) is very high in this circumstance relative to the population proportion. On average, each child in this group was exposed to 3.8 risks. This group has the highest proportion (97%) of families in the lowest income quintile and has the highest healthcare card use (84%). Importantly, the proportion of children in the Low Human Capital group with low school readiness (14%) is comparable to the overall population average.

Finally, the sixth circumstance we describe as Resource Poor non-English Speaking (7%). On average, each child in this group was exposed to 4.7 risks. This group included 44% of the non-English speaking mothers. It had an increased proportion of mothers with maternal psychological distress (42%), low parenting consistency (35%), four or more siblings (11%), low income (33%), healthcare card (35%), neighbourhood disadvantage (35%), and not reading to the study child (14%). This group did not show any increased likelihood for study child Indigenous status, child reactive temperament, or teenage motherhood.

With these groups now described, we wanted to know if their rates of developmental growth, as measured by vocabulary and literacy differed in initial starting levels and onward rates of growth.

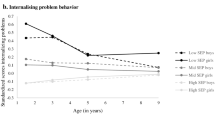

Children in Different Developmental Circumstances Have Different Rates of Growth

When we studied the rate of vocabulary growth in children from age 4 to age 8, there were striking differences in the rate of growth for children who were in each of these different developmental circumstances (Christensen et al., 2017). The findings demonstrate that developmental circumstances were associated with both differing initial starting levels of vocabulary ability and then, differing rates of onward growth. Importantly where there were similarities in starting levels of vocabulary and onward growth, there were differences in developmental circumstances that would need different policy prerogatives and intervention approaches in order to deliver better targeted interventions.

Developmentally Enabled children were characterised by “on time” vocabulary growth. That is, at each point of observation at ages 4, 6, and 8, these children’s vocabulary performance was, on average, appropriate for their age—they were “on time”. This group of children was used to compare the vocabulary growth of children in other developmental circumstances. What this showed was that children in the Working Poor circumstance started 5.8 months behind at age 4 and were almost 5.9 months late, or behind, in their vocabulary growth by the time they were 8 years of age—that is, they fell slightly further behind. Children in the Developmental Delay circumstances started 9.6 months behind and were 7.2 months late by the time they were 8 years of age, and children in the Low Human Capital circumstances were 6.1 months behind at age 4, and 4.7 months late in their vocabulary growth by the time they were 8 years—in other words, children in these groups were slowly catching up.

Children in the remaining groups showed even larger differences. Those children in the Resource Poor Non-English Speaking circumstance started 26.3 months behind at age 4, but had closed this gap to 10.4 months by the time they were 8 years. Children in the Overwhelmed circumstance started 18.9 months behind and were over a year behind—13.1 months—at age 8. As can be seen, each of these groups had different rates of growth with the Non-English Speaking group having the highest (most rapid) rate of growth. It could well be that these children would close this gap were we to observe them over a longer period of time.

How persistent are these patterns and circumstances over time? As noted above, longitudinal data on developmental growth are difficult to come by. One domain, however, that offers some scope for such study is school—specifically the growth of reading and numeracy. Australia conducts the National Assessment Program-Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) gathering information on these student competencies in school years (i.e., Grades) 3, 5, 7, and 9 covering the developmental range from approximately age 8 to 15 years. Using NAPLAN data, and a similar composition of ten risk exposures, continued to produce four classes of risk circumstances that represented substantively different developmental circumstances that influenced the onward growth of NAPLAN literacy (Taylor et al., 2019).

The largest group (62%) was again characterised as Developmentally Enabled and was characterised by a very low exposure to any of the modelled risks. Another 25% were in a circumstance characterised by, principally, Sociodemographic Risks with low maternal education, low family income, indigeneity, and area disadvantage predominating. Smaller proportions of children (11%) were in a Child Development risk profile with low school readiness, lower non-verbal intelligence and vocabulary, and low task attentiveness and behavioural problems. Finally, a very small proportion (2.4%) of children experienced Double Disadvantage with high exposures to risks spanning both Sociodemographic and Child factors.

These groups revealed differences in the growth of their reading competencies over time relative to the Developmentally Enabled group. Students whose circumstances were Developmentally Enabled in Year 3 had average reading achievements in Year 9 benchmarked at 10.4 years—they were ahead of their year level. However, students with a sociodemographic risk profile were 1.2 years behind the reference group in Year 3 and by Year 9, they had fallen 2.1 years behind their developmentally enabled peers. Students with a Child Development Risk profile were 2.0 years behind the reference group in Year 3 and by Year 9, had fallen 3.3 years behind their developmentally enabled peers. Finally, students with a Double Disadvantage risk profile were 2.7 years behind the reference group in Year 3 and by Year 9 were 5.3 years behind their developmentally enabled peers. These are substantial gaps in growth and development.

Comparing developmental effects for vocabulary and for reading competency in two studies from the same birth cohort illustrates that developmental circumstances are associated with marked differences in rates of growth in these capacities, and that the impact of developmental circumstances on school outstrips the effect of developmental circumstances on vocabulary.

Developmental Circumstances Reduce Participation in Interventions

Developmental opportunities and expectations are—of course—designed and offered with the intention of assisting children in their early development and, particularly, to assist those children who are vulnerable to or falling developmentally behind. Many of these opportunities and expectations take the form of participation in play groups, library programs, and early childhood education and care programs, and entry to, and attendance at school. Participation in these is explicitly designed to encourage optimal development, prevent developmental delay or disadvantage, or close emerging skill gaps in some children relative to others.

What are the relationships between the developmental circumstances we describe here and the likelihood of participating in these opportunities? School is one such opportunity and is notable because it is a socially sanctioned developmental expectation that is typically legislated and mandated for all children. Attending school is expected and school attendance offers one type of measure of exposure to a developmental opportunity that is explicitly organised to change child development.

Using LSAC data, Hancock et al. (2018) identified four classes of risk exposure (e.g., developmental circumstances). Most children (56%) were exposed to minimal risk, 20% were exposed to parenting, child development, and mental health risks only, 15% were exposed to a greater extent to financial risks only, and 9% had a higher probability of exposure to all risks. Hancock et al. (2018) found a great deal of heterogeneity in the association between persistent non-attendance at school and developmental circumstances. One-third of persistent non-attenders were actually in the low-risk circumstance. But, persistently non-attending children were eight times more likely to face circumstances characteristic of the high-risk group than regular attenders.

In another study, Taylor et al. (2021) examined a large population cohort of very young children from ages birth to 5 years to examine the participation of these children and families in universal early childhood services located in Tasmania, Australia. These universal services included community-based child health services, a parent-child early learning programme and entry into and participation in ECEC in Kindergarten.

Taylor et al. (2021) found patterns of participation by families and children and characterised these as Regular, Low and High service use. These service use patterns emerge at the outset of a child’s birth and remain stable over time and across different service types. That is, families with low participation in services tended to have low contact with all services throughout the five-year period. The finding that low service use was consistent across service types suggests that risk factors influencing levels of service use are not necessarily sector- or service-specific. The propensity or capability to participate appears to be a relatively fixed characteristic of children’s family and social circumstances. What these data show is that some vulnerable children remain in persistent circumstances that challenge current models of service delivery to reach them.

Intervention and Prevention Opportunities Matched to Places and Circumstances

The birth of a child into a family is most often heralded with celebration and excitement and is typically a welcome event. So much of the common narrative about child rearing and child development is narrated through the dual lens of time and money—two of the resources parents typically mention in the balance between work and family. In truth, time and income are but two of the several resource domains essential in the development of children. In addition, human capital, social capital and psychological capital are needed above and beyond just time and money (Zubrick et al., 2005, 2014). Child development is about growth and change. And in this chapter our focus has been on a narrow, albeit critical, component of that growth: Namely, vocabulary and literacy in the population of Australian children. These are two of the markers of the wider skill that language development entails.

What we have seen so far is that early growth (as measured by vocabulary acquisition and later literacy) is typically highly variable. Children of similar ages may commence their growth from higher starting points and with higher capacities than other children. Some children grow more rapidly than others and some children who may be developmentally “on track” at one point in time, may fall behind their peers at other points. The variability of this growth makes the prediction and selection of some children over others for developmental services, on the basis of their growth and performance at one point in time, at best, inefficient and at worst, inequitable.

What we have also seen is that while individual risks are individually and collectively poor predictors of changes in child development, their clustering, patterning, and persistence nonetheless imparts changes in the starting levels of their growth and the onward rate of this growth over time. Quite importantly, while some children outwardly appear to have similar rates of slower development, the underlying circumstances associated with this growth are different. These differences in developmental “circumstances” as we call them here, invite different approaches to how governments, agencies, and services plan and deliver developmental expectations and opportunities for young children and their families (Taylor et al., 2020).

Table 3.2 details some of the policy and service prerogatives for child development interventions and prevention strategies for which there is robust evidence of efficacy. These strategies are best thought of in terms of their impact on large populations or sub-populations of children. Clearly there are important universal strategies that apply across all developmental circumstances. Critically, children and families experiencing other circumstances would benefit from a wider, more selected or targeted range of services that address some of the unique features of their lived lives.

At the outset, it is important to appreciate that the absence of a tick in many of the boxes of Table 3.2, does not imply that the policy or service is not needed or relevant to other developmental circumstances. Instead, the indicators in Table 3.2 highlight where policies and service prerogatives are particularly relevant to the developmental circumstances we have studied here. Table 3.2 reflects where there are specific opportunities to improve developmental expectations and opportunities and how they impact on particular groups in need.

Two features of this schema should be highlighted here. First, consideration of the mix of these policies and services can be tailored to match developmental characteristics of community populations. Populations of children and families vary in their developmental circumstances and this variation is frequently spatially determined: By suburbs, regions, and areas. “Place-based” developmental planning can better match developmental circumstances to policy and service delivery. Population demography, service use characteristics, and data integrated from a variety of sources can be used to better select the mix of intervention opportunities for specific areas. Where funds are made available, how might these characteristics guide improvements best tailored to lift developmental capacities in these areas?

Second, it is important to also note the level at which the proposed policy or service prerogative is targeted. For example, a unique feature of families with Low Human Capital is the preponderance of children whose mothers are very young. These children, relative to children in the Working Poor or Overwhelmed circumstance, show a gradual growth in their early vocabulary. While these children undoubtedly benefit from universal services, their parents (mothers particularly) would also benefit from policies that support family planning and maintain maternal engagement in education and onward training and employment. In this instance, the target level of the intervention is a parent.

Conclusion and Discussion

This chapter has focused on variations in population child outcomes as they relate to changes and patterns in the growth of child language, literacy, and subsequent school attendance. These are benchmark performances that portend future capabilities as theorised by life course approaches to human capital development. We believe the benefit of modelling the characteristics of growth in early childhood is evident and that the findings suggest important ways of thinking about how we address early child development in the context of disadvantage.

Child development as modelled here shows us that it is highly variable over time and it is much more unpredictable than is typically presented. There are striking variations in the growth of young children that can be demonstrated in their starting capacities and in the onward rate of growth of these capacities. This variability predisposes children to move in and out of vulnerability and consequently their need for appropriate services and inventions.

The predictive utility, that is, the reliability and efficiency of predicting which children will do poorly, is very poor using a wide range of empirically selected risks. Predicting with certainty which children are behind or falling behind in their development will inevitably misclassify many at one point in time. Indeed, some who are not in need early will be found to subsequently need help. This means services and developmental opportunities need to have “open doors” across a wide developmental age range.

What emerges from this view of early child development is not so much about what “works” to improve child development—there is an ample evidence base detailing the range of effective strategies (see Table 3.2)— but rather, a challenge of “how” we arrange the provision of these opportunities through services and policies to meet the developmental circumstances of children. In addressing how we arrange provision of services and policies, there have been consistent calls for early developmental interventions and opportunities that are proportionately or progressively universal (Lynch et al., 2010; Marmot et al., 2010); That is, individuals across the population are entitled to benefits proportionate to their needs. But what does this actually mean in practice? How is “proportionality” or progressive universalism achieved?

Our findings suggest ways of thinking about this regarding early years interventions. First, recognise that at the earliest points of development, early years services and opportunities are best provided universally to all families and children with essentially no access or selection thresholds placed on means or needs. This is the entry point in life where services can assess, reach, invite, and establish developmental opportunities and begin to make provision for those in greater need. The major challenge here is ensuring that universal services are available and that they are obligated to pro-actively reach the population fairly and equitably.

Second, adjust intervention intensity and complexity against the distribution of developmental circumstances in area populations. Intervention intensity is more than just increasing the “dose,” or providing more of the same of an existing program or service offered to a family or child with greater needs. For example, families who are Overwhelmed are restricted in their very capability to participate. The issue for these families is not access to service—but the effort and manner by which services reach for them. Addressing this may entail eliminating social barriers by adjusting or implementing policies that guarantee fairness and equity and that provide additional means for reach, access and participation.

Third, in considering the challenges of establishing proportionality, Carey et al. (2015) highlight the essential need to “ensure that decisions and actions are taken as closely as possible to citizens through a multi-layered system” (i.e., subsidiarity). In Australia there is current enthusiasm for “place-based co-designed” services that are responsive to local circumstance and needs, and that are overseen and governed at the local level thereby empowering individuals, families, and communities. Place-based co-design is certainly in line with the Carey et al. schema for proportionality. But as the authors point out, subsidiarity is not an invitation for the higher levels of governance (State and Federal) to abandon their unique responsibilities to govern, legislate and fund in ways to guarantee fairness and equity in provision, access and reach.

In concluding this chapter we return to where we started. There is ample evidence that establishes that expectations and opportunities for children in their early years have a significant impact on their onward capabilities and choices as theorised by life course perspectives and as shown by many empirical studies. While we believe that prevention interventions in the early years have small effects this is not to say that we believe these effects to be trivial or insignificant. To the contrary, it is our view that the variability of growth within and between children reflects the very nature of how development typically occurs.

What we also show is that disadvantage is heterogenous in its effects on child development. This heterogeneity reveals itself in the different developmental circumstances we document in this chapter. Many children are developmentally enabled and progress through their early years relatively unimpeded and without delay and with parents who are seeking optimal outcomes for them. But for many other children development is less orderly, more variable, and accompanied by individual, family and community circumstances that are associated with slower growth and gaps in their development that widen substantially into the middle years. For these children, developmental science documents what works to effectively prevent or reduce these gaps. Our work in this chapter invites a broader research and discourse in how we arrange these expectations and opportunities and create circumstances for better guided actions on the part of governments, agencies and individuals.

References

Anglin, J., Miller, G., & Wakefield, P. (1993). Vocabulary development: A morphological analysis. Monographs for the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(10), 1–186. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166112

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2014). Childhood education and care survey (Cat. 4402.0). Retrieved from Canberra.

Baxter, J. A. (2015). Child care and early childhood education in Australia (Facts Sheet 2015). Retrieved from Melbourne.

Baxter, J. A., & Hand, K. (2013). Access to early childhood education in Australia (Research Report No. 24). Retrieved from Melbourne.

Campbell, F. A., Pungello, E. P., Burchinal, M., Kainz, K., Pan, Y., Wasik, B. H., … Ramey, C. T. (2012). Adult outcomes as a function of an early childhood educational program: An Abecedarian Project follow-up. Developmental Psychology, 48(4), 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026644

Carey, G., Crammond, B., & De Leeuw, E. (2015). Towards health equity: A framework for the application of proportionate universalism. International Journal for Equity in Health, 14(1), 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0207-6

Christensen, D., Zubrick, S. R., Lawrence, D., Mitrou, F., & Taylor, C. L. (2014). Risk factors for low receptive vocabulary abilities in the preschool and early school years in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. PLoS One, 9(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101476

Christensen, D., Taylor, C. L., & Zubrick, S. R. (2017). Patterns of multiple risk exposures for low receptive vocabulary growth 4–8 years in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. PLoS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0168804

Duncan, G. J., & Magnuson, K. (2013). Investing in preschool programs. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27(2), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.27.2.109

Dunn, L. M., Dunn, L. M., & Williams, K. T. (1997). Peabody picture vocabulary test-III. American Guidance Service.

Evans, G. W., Li, D., & Whipple, S. S. (2013). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1342–1396. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031808

Fenson, L. M. V., Thal, D., Dale, P., Reznick, J., & Bates, E. (2007). MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories, user’s guide and technical manual. Brookes.

Gutman, L. M., & Schoon, I. (2014). The impact of non-cognitive skills on outcomes for young people. Literature review, 21 November 2013. Institute of Education.

Hancock, K. J., Mitrou, F., Taylor, C. L., & Zubrick, S. R. (2018). The diverse risk profiles of persistently absent primary students: Implications for attendance policies in Australia. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10824669.2018.1433536

Heckman, J. J. (2006). Skill formation and the economics of investing in disadvantaged children. Science, 312(5782), 1900. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1128898

Kagan, J. (2018). Kinds of individuals defined by patterns of variables. Development and Psychopathology, 30(4), 1197–1209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941800055X

Lynch, J. W., Law, C., Brinkman, S., Chittleborough, C., & Sawyer, M. (2010). Inequalities in child healthy development: Some challenges for effective implementation. Social Science & Medicine, 71(7), 1244–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.008

Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., Boyce, T., McNeish, D., Grady, M., & Geddes, I. (2010). Fair society, health lives: The Marmot review. Retrieved from London, UK.

McLaughlin, K. A., & Sheridan, M. A. (2016). Beyond cumulative risk: A dimensional approach to childhood adversity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(4), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721416655883

Niles, M. D., Reynolds, A. J., & Nagasawa, M. (2006). Does early childhood intervention affect the social and emotional development of participants? Early Childhood Research and Practice, 8(1).

Powell, D., & Diamond, K. (2012). Promoting early literacy and language development. In R. Pianta (Ed.), Handbook of early childhood education (pp. 194–216). The Guilford Press.

Reilly, S., Wake, M., Ukoumunne, O. C., Bavin, E., Prior, M., Cini, E., … Bretherton, L. (2010). Predicting language outcomes at 4 years of age: Findings from early language in Victoria study. Pediatrics, 126(6), e1530. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0254

Schweinhart, L. J. (2013). Long-term follow-up of a preschool experiment. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 9(4), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-013-9190-3

Shonkoff, J. P. (2016). Capitalizing on advances in science to reduce the health consequences of early childhood adversity. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(10), 1003–1007. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1559

Tayler, C. (2016). The E4Kids study: Assessing the effectiveness of Australian early childhood education and care programs Overview of findings at 2016. Retrieved from https://education.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/2929452/E4Kids-Report-3.0_WEB.pdf

Taylor, C. L., Maguire, B., & Zubrick, S. R. (2011). Children’s language development 0–9 years. In Australian Institute of Family Studies (Ed.), The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children Annual Statistical Report 2010. AIFS.

Taylor, C. L., Christensen, D., Lawrence, D., Mitrou, F., & Zubrick, S. R. (2013). Risk factors for children’s receptive vocabulary development from four to eight years in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. PLoS One, 8(9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0073046

Taylor, C. L., Zubrick, S. R., & Christensen, D. (2019). Multiple risk exposures for reading achievement in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, jech-2018-211323. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-211323

Taylor, C. L., Christensen, D., Stafford, J., Venn, A., Preen, D., & Zubrick, S. R. (2020). Associations between clusters of early life risk factors and developmental vulnerability at age 5: A retrospective cohort study using population-wide linkage of administrative data in Tasmania, Australia. BMJ Open, 10(4), e033795. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033795

Taylor, C., Christensen, D., Jose, K., & Zubrick, S. (2021). Universal child health and early education service use from birth through Kindergarten and developmental vulnerability in the Preparatory Year (age 5 years) in Tasmania, Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.186

Vasilyeva, M., & Waterfall, H. (2011). Variability in language development: Relation to socioeconomic status and environmental inputs. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early literacy research (pp. 36–48). The Guilford Press.

Zubrick, S. R. (2016). Longitudinal research: Applications for the design, conduct and dissemination of early childhood research. In A. K. Farrell, S. L. Kagan, & K. Tisdall (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of early childhood research (pp. 201–222). Sage.

Zubrick, S. R., Silburn, S. R., & Prior, M. (2005). Resources and contexts for child development: Implications for children and society. In S. Richardson & M. Prior (Eds.), No time to lose: The well being of Australia's children (pp. 161–200). Melbourne University Press.

Zubrick, S. R., Taylor, C. L., Rice, M., & Slegers, D. W. (2007). Late language emergence at 24 months: An epidemiological study of prevalence, predictors and covariates. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 50, 1562–1592.

Zubrick, S. R., Lucas, N., Westrupp, E. M., & Nicholson, J. M. (2014). Parenting measures in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children: Construct validity and measurement quality, Waves 1 to 4. Research Publications Unit, Strategic Policy Research. Retrieved from http://www.growingupinaustralia.gov.au/pubs/technical/index.html

Zubrick, S. R., Taylor, C. L., & Christensen, D. (2015). Patterns and predictors of language and literacy abilities 4–10 years in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children. PLoS One, 10(9), e0135612. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135612

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zubrick, S.R., Taylor, C., Christensen, D., Hancock, K. (2022). Early Years and Disadvantage: Matching Developmental Circumstances in Populations to Prevention and Intervention Opportunities. In: Baxter, J., Lam, J., Povey, J., Lee, R., Zubrick, S.R. (eds) Family Dynamics over the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-12223-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-12224-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)