Abstract

Loneliness is emerging as a significant issue in modern societies with impacts on health and wellbeing. Many of the existing studies on loneliness focus on its contemporaneous correlates. Drawing on life course and cumulative disadvantage theory and data from qualitative interviews with 50 older adults living in the community, we examine how past events shape variations in later-life loneliness. We identify four factors that are of significance for understanding loneliness: (1) Formation of social networks; (2) history of familial support; (3) relocation and migration, and (4) widowhood and separation. Our findings point to the importance of maintenance of social ties over the adult life course while at the same time highlighting how disruptions to social networks impact on later-life loneliness. We also find that loneliness and disadvantage, like other social or health outcomes, compound over time.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

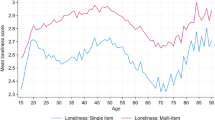

Loneliness is the discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships, both in terms of quality and quantity (Cacioppo et al., 2015). Loneliness has received much attention in recent years, and has been especially highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic (Luchetti et al., 2020; van Tilburg et al., 2020). Older adults are one population of concern for loneliness, as age and loneliness have a U-shaped relationship, with young adults and young-old adults (65–85 years old) experiencing the highest prevalence of loneliness (Nicolaisen & Thorsen, 2017; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001). An Australian study found that loneliness prevalence among Australian older adults closely resembles that found overseas in Europe and Great Britain, with 7% of older Australian adults in their Western Australian sample severely lonely, and a further 31.5% sometimes lonely (Steed et al., 2007). A more recent study using data from the nationally-representative Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey reports that 16.1% of older adults (65+ years) reported loneliness, agreeing with a single-item statement ‘I often feel very lonely’ (Kung et al., 2021). Loneliness is significant through its associations with a range of health and wellbeing outcomes (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2016) including higher all-cause mortality (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015; Leigh-Hunt et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2012; Rico-Uribe et al., 2018) and dementia (Rafnsson et al., 2017).

This chapter draws on interview data with older adults to examine how experiences throughout the life course may explain variation in later-life loneliness. This shows that loneliness, like other social or health outcomes, is not only the result of current circumstances and conditions, but may be traced back to earlier life events. Thus, the reduction of later-life loneliness requires not just examining circumstances at the later life stage but may be supported by intervention earlier in the life course. Literature on the correlates of loneliness to date has focused predominantly on contemporaneous factors, such as partner status, living arrangements, health and socioeconomic status (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2016; De Koning et al., 2017; Pinquart & Sorensen, 2001). Some studies also pay attention to how experiences of life-changing events, such as widowhood or divorce, may also lead to subsequent changes in loneliness (Dahlberg et al., 2015; Peters & Liefbroer, 1997). Lim et al. (2020) describe a conceptual model in which entry into loneliness depends on ‘triggers’; that is, life events associated with a change in social identity.

While there is robust evidence of the significance of these factors, unexplained variation remains which may be better explained by a life course perspective. This is because even in longitudinal studies of loneliness, researchers may often overlook the importance of stability of family and work life conditions and circumstances, given their inherent focus on change, or the observation of varied events (Dahlberg et al., 2015; Dykstra et al., 2005; Victor & Bowling, 2012). The timeframes focussed upon in such research, ranging from 5 years (Newall et al., 2014), to 20 years (Wenger & Burholt, 2004), and 28 years (Aartsen & Jylhä, 2011), as well as a focus on changes observed in later life, may also overlook factors or events that may be of significance up to that point in the adult life course.

Taking a qualitative, inductive approach, we highlight important explanatory factors of later-life loneliness. Our findings point to four themes that are significant for understanding later-life loneliness, namely: (1) history of familial support; (2) formation and maintenance of social networks; (3) relocation and migration; and (4) widowhood and separation. These highlight the importance of continuity of social ties and the impact of change on later-life loneliness. In the next section, we start to build the case for examining earlier life influence. We draw on the life course perspective and cumulative disadvantage theory to underscore the value of taking a broader view of the adult life course to understand later-life loneliness.

Literature Review

A body of research has investigated the prevalence, correlates, and predictors of loneliness among older adults (65+ years old). The literature describes a multifaceted relationship between old age and loneliness that is mediated by changes in physical, social and psychological circumstances that occur during aging (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2016). Loneliness is an important issue and has been found to relate to a number of socio-demographic factors, including partnership status (Boger & Huxhold, 2020), health (Burholt & Scharf, 2014), educational attainment (Bishop & Martin, 2007), and economic status (Hawkley et al., 2008).

Being partnered is a protective factor against loneliness, although the quality of the relationship is a significant moderator. Having a supportive partner is associated with lower levels of loneliness while having a strained partner relationship is associated with higher levels of loneliness (Shiovitz-Ezra & Leitsch, 2010). Studies of older adults’ social networks consistently find that having a diversity of social ties is related to the lowest levels of loneliness (Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011). Better health, higher income and wealth as well as higher educational attainment are also related to lower levels of loneliness (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 2016; Savikko et al., 2005). Higher income and educational attainment may afford an individual the resources to access and participate in more social activities, offsetting the risk of loneliness (von Soest et al., 2018).

Prospective studies have also recently begun to investigate how the experience of specific events or life stage transitions may relate to changes in loneliness, particularly those typical in later life. Changes in marital status, health, social networks or living arrangements are associated with increased loneliness, because they frequently lead to losses to independence, mobility and social participation (Victor & Bowling, 2012). The loss of a supportive partner through widowhood for instance is strongly associated with increased loneliness (Dahlberg et al., 2015). Declines in health status, such as in functional health, vision and hearing, are associated with increased loneliness, possibly because they create barriers to social interactions (Savikko et al., 2005; Dykstra et al., 2005). Negative changes may have a stronger impact than positive ones, with health declines associated with a greater magnitude of increase in loneliness when compared with improvements in health and their association with decreases in loneliness (Dykstra et al., 2005). Overall, partner status, relationship quality, health, and economic, social and educational resources are all key factors associated with loneliness.

The Life Course Perspective and Mechanisms Linking Life Course Disadvantage and Later-Life Loneliness

The life course perspective suggests that the trajectory of a person’s life is shaped by the sequence and timing of life events. These are influenced by their historical and geographical location, and importantly for the study of loneliness, also by their own agency, and relationships with others—‘linked lives’ across their life course (Elder & Giele, 2009). Under this perspective, it can be expected that the cumulative effect of life events over the life course, such as childhood positive and negative experiences, partner status, parental status, bereavement, and migration experiences, influence the experience of later-life loneliness in ways that contribute to, but may be distinct from, the current situation of the older adult.

Cumulative disadvantage theory states that negative events or conditions can compound over the life course. We understand loneliness as a phenomenon in relation to the existence and quality of a social network, filtered by an individual’s perception. Thus, cumulative disadvantage is expected to be relevant to loneliness in two ways; through its influence in shaping a supportive social network across the life course, and through the development of psychological skills for coping with loneliness-provoking social contexts, such as a sense of agency and self-efficacy (Fry & Debats, 2002; Gerino et al., 2017). Early inequalities may not only limit the direct opportunities for development of appropriate social and psychological skills, but also influence other life domains. Social advantage increases exposure to social opportunities, such as stable living and working arrangements which maintain stable social relationships, or sufficient resources and good health to enable high levels of social participation. These circumstances may then afford people further opportunities for social support and connection. Conversely, disadvantage in one of these life domains may increase the risks of psychological and financial stresses, placing the individual at greater risk of isolation from their social network. Examining loneliness among older adults as a function of their life course experiences provides the benefit of describing the mechanisms linking past events and present circumstances.

Longitudinal and retrospective research linking a range of childhood and adult experiences with later-life loneliness adds credence to investigating loneliness through cumulative disadvantage. These studies tend to focus upon diminished later life social resources as the key domain of disadvantage relevant to loneliness, suggesting that disadvantage compounds as a result of either maladaptive social skills (Ejlskov et al., 2020; Hensley et al., 2012), or social censure or conflict (Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer, 2018; Wu & Penning, 2015). Negative childhood experiences, including poverty or lack of positive engagement with parents, are associated with loneliness in later life (Merz & de Jong Gierveld, 2016; Kamiya et al., 2014). These retrospective studies suggest, as a mechanism, developmental deficiencies which persist into adulthood, such as a lack of parental investment in childhood social development which affects the social skills at their disposal (Case et al., 2005) or the development of maladaptive attachment behaviours (Andersson & Stevens, 1993). These mechanisms of impaired social abilities originating in childhood are not overcome, but continue to affect the individual throughout their life, although these studies do not investigate to what extent they affect subsequent life events. The extant studies which have considered social or other adversities that occur during adulthood (Ejlskov et al., 2020; Peters & Liefbroer, 1997) are limited because they are most interested, not in the accumulation of disadvantages, but in loneliness effects which remain for older adults independent of their current social situation. They find that previous experiences of damaged or lost relationships are associated with increased loneliness independent of current social relationships. This suggests that continuity in relationships is protective against loneliness. A cumulative disadvantage perspective highlights that inequalities like low income, poor education, or poor health may directly influence available social opportunities across the life course, thus significantly differentiating individuals’ risk of loneliness by the time that they reach old age.

Divergence from the normative script of life events, such as delays or non-entry into partner relationships and parenthood, is also related to later-life loneliness. This confirms the relevance of applying a life course perspective to the study of loneliness, with its interest in the sequence and timing of events. The suggested mechanisms consist of social censure or lack of support from surrounding social networks, or life-long lack of a common source of social or material support (Zoutewelle-Terovan & Liefbroer, 2018; Van Humbeek et al., 2016). However, the loneliness associated with singlehood may be moderated by the role of choice or constraint, with those who never married by choice expressing satisfaction in their later life, while those who were never-married by constraints—such as caring responsibilities or economic factors—experience loneliness and discontent with their unmarried status (Timonen & Doyle, 2014). Other proposed moderating factors are the role of stability throughout the life course (Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 2004), or the practice of ‘anticipatory socialization’ to maintain the personal and social resources required for wellbeing (Koropeckyj-Cox, 1998). This suggests that where single people have exercised agency over their own social circumstances, they are less susceptible to loneliness.

These findings regarding human agency introduce an important counterpoint for avoiding a determinist interpretation of the accumulation of disadvantage. The life course perspective affirms that within their constrained circumstances, people plan and make choices (Elder & Giele, 2009). Resilience can be understood as a deliberate, purposive response based on recognition of one’s structural circumstances (Schafer et al., 2009). In relation to loneliness, where the person perceives themselves to be in an adverse social situation, resilience consists of being able to identify corrective action to counter the adversity, and being able to activate appropriate resources to do so (Schafer et al., 2009). These may be practical, social, or psychological resources, as older adults seek to make changes within their activities or social networks or reframe their experiences within the context of their life, in order to reduce their loneliness. Resilience is not a magic bullet, because it depends upon the ability to mobilise resources. Cumulative disadvantage theory highlights that events which diminish these resources can be expected to have ongoing, compounding effects exposing the individual to greater risks of social losses with fewer opportunities for social gains. As a result, we may expect older adults to recall a range of adulthood factors that play a role in their understanding of later-life loneliness.

Data and Methods

This chapter draws on data collected as part of a broader research project “Understanding Daily Activities in Later Life” which aimed to provide up-to-date evidence on the experience of daily activities and loneliness for a group of older Australians. It has a specific focus on understanding the patterns and rhythms of daily life and how these relate to older Australians’ wellbeing. It was designed and conducted with the assistance of a home care organisation in Southeast Queensland, Australia. This mixed-methods project comprised an initial survey that was conducted to collect data on health, social interactions, family structure and personal relationships. A total of 182 older individuals (aged 65 years plus) returned the self-report questionnaire. From this sample, a subset of 50 individuals who represented a range of socio-demographic characteristics was then selectively contacted for follow-up one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Queensland.

Interviews took place at the location of choosing of respondents. The majority took place in home residences, with the exceptions being in the common area of 7 retirement villages or the lobby of apartment buildings. The interviews ranged from around 30 minutes to 2 hours. During the interview, we attempted to get a sense of the daily lives of the respondents, posing statements such as “Tell me about your day yesterday,” “Tell me about your week this past week” and “Tell me about your relationships and support”. Given that the interviews were semi-structured, respondents also at times discussed their life histories, providing a broader overview of how they understood their current circumstances in relation to past events. They likely felt further encouraged to reflect in this way by the questions “Have you experienced any major life events recently? Has that changed anything in your life?”. For example, in one interview, a participant described his whole family life history, from the time of birth while describing this alongside a photo album of photos since his childhood, documenting various events along the way. Although this is one extreme, as the respondent was engaged in a project around his family ancestry, other participants also brought up discussions around past life events.

The mean age of the respondents was 82, and the overwhelming majority were women. About half were widowed (50%), a quarter married (28%), and the remainder divorced, separated, or never married. The average respondent reported being ‘reasonably comfortable’ in terms of their financial situation and reported being somewhere between ‘good’ and ‘moderate’ in terms of their health.

Interviews were recorded with the consent of the participants and audio files were transcribed and uploaded onto a qualitative software, NVivo, which we drew on to further analyse the data. We undertook inductive coding to explore themes that might arise from the interview data. The lead author and two undergraduate research assistants coded several of the same interview transcripts and met at the initial stages to establish inter-rater reliability. As the analysis progressed, the research team met and established fifteen distinct themes. For the purposes of the current chapter, we focused on data with mentions of past events and family life history to understand how these are significant factors for the respondents’ current circumstances. While respondents often focussed discussion on present-day activities and relationships, such as around care arrangements, discussion of the past was quite common around themes such as family, friendships, support network, and community. From these, our data highlights for older adults in our sample the importance of different factors that relate to their loneliness.

Results

Our findings highlight the importance of social network and ties over the life course for understanding later-life loneliness. While prior research examining the impact of life events on later-life loneliness highlights the role of change (via an observed event), it has paid less attention to the importance of stability and history of family social support. Our data however highlights this as a crucial factor. Not only is stability of social ties highlighted, but the role of human agency is instrumental in shoring up family support as well as in creating a support network. Consistent with previous research, our findings also showed that the experience of events such as migration and relationship dissolution impact on later-life loneliness through the disruption of ties. While existing studies have primarily focused on the occurrence of such events in later life, for example the observation of events at age 50 or older as is common in most gerontological studies, our study highlights how events earlier in the life course are also of significance and have longer term implications. Our findings show the importance of four themes: history of familial support, formation of social networks, relocation and migration, and widowhood and separation.

History of Familial Support

Support from the family unit throughout the life course was linked to decreased later life loneliness. Many participants associated the support, or lack thereof, of their family across the life course with lesser, or greater, feelings of loneliness in later life. Several participants identified how they developed a familial culture of support across their life history. One participant detailed the culture of open and honest communication that had developed in their family from a history of encouraging conversation with one another, “We’ve always believed in family discussion and I think that’s a lot of it where they’ve picked up things from me” (Female, Aged 86, Widowed, Living Alone). The participant detailed how this led to a “very, very close” family relationship, which did not leave her feeling at all isolated. Other participants echoed this sentiment, benefitting socially from close relationships with their family members.

Another participant indicated that their family had become geographically distant over the years, and throughout their family history there had been few occasions where the family had come together as adults. The participant stated, “It just doesn’t kind of work that way in our family.” (Female, Aged 88, Married, Living with Spouse). Yet, after a traumatic health event that led to the hospitalisation of her and her spouse, the family converged from all over the world and were immediately present to assist. This family event shifted her perception of her connection with her family. She stated, “It taught me about my family and the care and the fact that each one contributed some of their own specific gifts to me at that time, their specific caring gifts.” This highlights both that across her family history she had cultivated social ties that could be called upon in times of need, and that this life event acted as a catalyst for her family network to connect with her differently, changing her perception of the social support available to her. A widowed woman aged 88 and living alone, also highlighted the social support she received from close relationships with all of her children, especially in the aftermath of her husband and brother passing away. Another widowed woman (77, living alone) described a sequence of events which had left her a self-described “hermit”. Like the others, after the death of her spouse, her daughter had provided her with a sense of available support, as she also dealt with health issues that limited her ability to leave the home for social engagements. It was only after her daughter’s subsequent move to another state that she felt a lack of support, describing herself as “a ship in the ocean; drifting”, demonstrating the compounding influence of successive life events.

Other participants identified alternate positive outcomes from vastly different family histories. One female participant, aged 75, talked of her life as a single person, having never been married. She claimed this as being a large mitigating factor in avoiding loneliness in later life. She attributed loneliness to the isolation of widowhood, and stated, “They haven’t got [the same skills as me] because I’ve been by myself and I’m single.” (Female, Aged 75, Never Married, Living Alone). The skills developed across the life course as a single person were identified as steeling her against events in later life that would, speculatively, cause loneliness in others. Another woman, aged 75 and living with her spouse, credited her upbringing in a rural setting with an ability to “just get on with it” in older age.

Some participants tended to attribute loneliness to distance from family, both emotionally and physically. A participant described a series of accusations that had been levelled at her by her daughter. This caused a discrepancy between her ideal relationship with her daughter, and her actual relationship, “It’s not as warm as it used to be, or as warm as I’d like it to be.” (Female, Aged 82, Married, Living with Spouse). Another participant, aged 77, widowed and living alone, spoke of the physical distance from her cousins. After the death of her parents early in life, she was raised by her aunt, and these cousins were essentially adoptive sisters. However, in later life, one of these cousins was situated in Sydney and the other had recently moved into a nursing home. The participant implied that this geographical isolation from her closest family heightened her feelings of loneliness.

There were also those that accounted for stronger feelings of loneliness and isolation through descriptions of their early life history. A 100 year-old lady, widowed and living alone, spoke of the deaths of her parents and sister. With these deaths, her relationship with her nieces soured and left her isolated from family members.

Formation of Social Networks

A second theme of the findings was the role of the formation of social networks. In accordance with the literature, the formation and maintenance of social networks across the life course proved to be a strong theme through the project’s interviews. There were a variety of perspectives provided as to how these networks developed, and how they are best maintained in later life.

Several participants discussed forming and maintaining social networks through formal social, hobby or activity groups. A female participant, aged 91, widowed and living alone, spoke of the importance of cultivating a strong social network early in the life course and carrying it into old age. The woman anecdotally evidenced this with her craft, church, and tennis groups that she had regularly attended for many years. She stated, “I think it’s something you need organised before you get retired. Just think about it when you’re young … Get into something, because it does help immensely.”

There were other accounts of the importance of formal socialisation. One woman, aged 76 and widowed, spoke of the social benefits she had received from a book club that she had been a part of for the best part of a decade. Another woman, aged 88 and married, continued to engage with choirs and craft groups into later life. She reported a benefit from being able to utilise skills and interests developed earlier in the life course. The participant advocated, much like others, for older people to “make an effort to join a group” in order to curb isolation.

Similarly, another participant, a 79 year old male living with his spouse, encouraged older people not to be forced into being a part of programs they have no interest in, but to, instead, maintain connection with people they enjoy the company of. His perspective was grounded in a “men’s group” that he had formed with some acquaintances earlier in life, as well as networks through church and exercise. The men’s group was explicitly identified as being a “mutual help society”, which provided an important source of social support. He attested to the social power of being a part of formal social groups, stating, “Get into the groups … which allow you to understand other people like you.” There is a clear consensus through all of these accounts that there is a social benefit to seeking out formal networks of others that align with one’s interests or hobbies.

There was another identifiable theme of building networks through local community. One widowed woman, aged 76 and living alone, spoke of the friendships she had maintained in the tight area around where her children had gone to school. Another participant spoke of the social value brought to her by neighbours she had when her children were young. It is clear that the community situation had played an important role in the formation of social networks across the life course. When discussing the current structure of her social networks, one female participant stated, “I’ve worked with either in nursing or we’ve worked in the same organisation. So, we have been friends for many years. I’ve been [in this house] since 1966.” (Female, Aged 80, Divorced, Living Alone). This outlines the importance of life course consistency in maintaining a social network.

The conclusion implied or stated by many of these individuals is that a diverse and active social network, vital for the mitigation of loneliness in later life, is a product of developing connections across the life course. A female participant succinctly summarised this point in answering whether her current friend group was more new or old friends, “It’s over a lifetime really. You make new friends and then they sort of become old friends … It’s a matter of coordinating everything. That’s more difficult than making new friends.”(Female, Aged 83, Widowed, Living Alone). She makes it clear that developing new friends across the life course ensures a pool of established social support in later life, but made the point that maintaining these networks is more complex than establishing them. Similarly, a 66-year old female participant describes, “around the 90s I met a group of friends who I’ve maintained… I know other people, but I tend to like just seeing good friends occasionally.” This reliance on the maintenance of longstanding connections for close connections in older adulthood highlights the importance of stability and the risk posed by late-life social network disruptions.

There were others, however, that were less optimistic about maintaining and developing social connection in later life. Some participants indicated that a breakdown of socialisation and growth of isolation were inevitable in older age. An example of this comes from a woman, aged 81, widowed and living alone, who detailed how her social group had broken down after her husband passed away and other members began to move into retirement living. These events, widowhood and retirement living, are closely linked to the later life course, leading to increased social isolation in later life. Another participant outlined the difficulty faced by already isolated older people, “Sometimes if they haven’t got a network of friends when they’ve been fit and healthy, then it’s very hard to get a network going when you’re not well and not going outside the house. So I think it starts a lot earlier.” (Female, Aged 83, Widowed, Living Alone).

Relocation and Migration

We also found that migration was a key event that affected feelings of loneliness. There were frequent suggestions from participants that relocation, both international and in-country, as an event from any point across the life course, played a large part in increased isolation and, consequently, increased feelings of loneliness in later life. For instance, one widowed woman, aged 92 and living alone, detailed losing social connections after moving to South-East Queensland from elsewhere in Australia. She stated, “We used to live in Sydney. Once you move, you lose contact with friends.” She discussed the adverse effects of that relocation in relation to the impacts of the death of close friends in Queensland. This suggests that she felt that she had decreased social support, due to migration, in those times of grieving. Another participant detailed a near-parallel story. She stated that friendships formed through church groups and raising children had “kind of dwindled” after moving to the city from a relatively nearby town (Female, Aged 81, Widowed, Living Alone). One other woman, aged 86, widowed and living alone, spoke of leaving well-established social networks in New Zealand and in New South Wales to move closer to family in Queensland. She spoke about not being able to click with similar social groups as she had earlier in life, and stated, “I don’t think I have any friends. I had a lot of friends.” The timing of relocation during the life span was significant to participants, with another participant articulating, “When you move to someplace when you’re older you don’t have the same friendships really.” Conversely, other participants highlighted that residing in the same area for 60+ years had supported long-term friendships (Female, 80 Years Old, Divorced, Living Alone), with one woman noting that 12 friends came to her birthday party, expressing pride in these long-standing friendships (Female, Aged 74, Divorced, Living Alone). Although they came from “up the coast, down the coast” to attend, it is clear that her long-term friendships were supported by her network remaining within travelling distance over many decades.

There was a recurring theme of people relocating in order to be geographically closer to their children. In these cases, there were mixed accounts of people feeling separated from their developed networks while also feeling increased social support from family. One female participant, aged 83 and widowed, spoke explicitly of experiencing this. The relocation, reportedly, led to conflicting experiences of losing easy access to her social networks developed through the life course, but having increased social support available to her from her family. Others discussed the influence family had on this decision, considering the opinion of their family members more important than any material or social connections with long-term friends (Female, Aged 90, Widowed, Living Alone). One 86-year old widow identified her daughter’s move overseas as a “trigger” for her own move to Brisbane, to be near other family members (Female, Aged 86, Widowed, Living Alone).

There was also evidence of later-life impacts from immigration and relocation earlier in the life course, though there was less indication that this impacted feelings of loneliness than for later-life relocation. A woman, aged 85 and widowed, spoke of the experience of moving throughout Africa and developing social networks with her husband. She implied that, while possible, maintaining any firm handle on these connections became difficult with relocation to Australia and then to South-East Queensland in later life. Another participant spoke of feelings of loneliness and associated them with an inability to develop social networks over the life course due to a transient life of constant relocation. This man, aged 79, separated and living with his child, talked of moving all over Australia for work throughout his life. He identified some social connections formed in later life, but he expressed that his only long-term social support figure, his wife, had been lost with an Alzheimer’s diagnosis and subsequent move to a support facility. Two further participants talked about their immigration experience earlier in life, from Germany (Male, Aged 87, Married, Living with Spouse) and England (Female, Aged 86, Widowed, Living Alone). While they showed some signs of connection to their respective places of origin, there was no clear indication this impacted on their feelings of loneliness.

A final participant associated relocation with a decrease in loneliness. This was an outlying case that incorporated a variety of factors including re-partnership and a move to be closer to his partner’s family. His outlook on this major shift was that any people of importance would work to stay in touch, “We shifted to start a new life, and if they want you, they’ll come after you, and you’ve got to go with that.” (Male, Aged 83, Married, Living with Spouse). With this framing, he assigns himself a non-active role in the maintenance of social ties. This attitude may be protective against loneliness because reduced connections are thus not understood as an avoidable lack or internalised as the result of a personal failing. However, it is also possible that he had simply developed a sufficiently supportive social network post-relocation.

Widowhood and Separation

Participants revealed that a history which involved a separation event could drastically affect social connection and feelings of isolation in later life, in a variety of ways. Several participants attributed feelings of loneliness to the deaths of their significant others. These feelings were commonly associated with the deep connection that forms between spouses over the life course. Participants highlighted the connection formed in 71 years of marriage (Female, Aged 95, Widowed, Living Alone) and, when asked if there were any wishes that they had, expressed the desire to have a husband back (Female, Aged 82, Widowed, Living Alone). One participant succinctly summarised this sentiment, stating, “You need someone who understands you and knows your weak points and your good points and your… everything.” (Female, Aged 92, Widowed, Living Alone).

There were implications of widowhood on broader social networks. An 81-year-old, widowed woman who lived alone, noted how, since the death of her husband, her connections with her social group had gradually deteriorated. She stated, “[Connection with my social group] has disintegrated, because, first, my husband went … So yeah, that’s sort of something you can’t control any longer.” The way in which she talked portrayed a perception of inevitability surrounding this decline in social interaction. Another 91-year-old participant described how she felt most alone after the death of her spouse because she no longer had someone to talk to about her day when she returned to an empty house, and this diminished her enjoyment of social outings.

Divorce was also described by some as a factor that impacted on their loneliness. One divorced woman, aged 81 and living alone, described the isolation that resulted from her marriage breaking down earlier in life. When asked about her current mental state, the participant described having experienced deep depression and resentment caused by the separation that made her earlier life “unmanageable”. However, she framed this experience as one that had built her resilience in the face of recent conflict with her daughter and a relocation: “When you’re a few disasters over the way, you learn a bit.” She describes actively making choices to maintain her friendships, such as ensuring that her new residential address was close to public transport, and does not feel lonely in the present.

Interviews indicate that modelling loneliness as a linear function of widowhood events is not a certainty. Several participants detailed the complexities of their relationships with their significant other, indicating that their separation had actively benefitted them. One widowed woman, aged 86 and living alone, detailed that her 60 year marriage had been more of a long-run “pal”, and the marriage never resulted in the participant feeling love. The interview made it clear that, while there was clearly a sense of loss, the loss of her partner did not impact on her as would be normatively expected of a typical widowing. Another perspective was brought by a widowed woman, aged 76, who accounted for her continued unmarried status with an unhappy marriage to her late husband. The participant described an unwillingness to pursue any future partnership with men as, she perceived, the patriarchal nature of marriage is overly controlling. She described her situation, “You’re lonely, but it’s peaceful.” She identifies feelings of loneliness, but utilises the term outside of its usual negative connotation.

Finally, one male participant, aged 83 and living with his spouse, detailed how re-partnership had mitigated feelings of loneliness in the wake of widowhood. After re-marriage, the newlyweds moved to a different area and found it easy to rebuild a social network as a couple. The man indicated that, in general, married couples seem to be happier and less lonely than those on their own.

Conclusion

The insights offered in this chapter demonstrate how a life course perspective can contribute to advancing our understanding of later-life loneliness. While the contemporaneous correlates of loneliness are well established, and research has indicated an association with earlier life events, the qualitative accounts in this study extend this body of knowledge by describing which life events are relevant, and the processes by which they may lead to loneliness among older adults. The principles of the life course perspective provide a useful lens for interpreting these findings, particularly linked lives and human agency, which were applied throughout to explain the four key themes within the findings. These themes were the formation of social networks, migration and relocation, a history of familial support, and widowhood and divorce. Across these themes, the findings provide further detail to three broad observations about the nature of loneliness; that social support develops over the life course and is difficult to replace at later stages, how individuals’ perceptions of their circumstances shape their loneliness, but also sometimes empower them to take action, and the varied effects of relationship disruptions, particularly with family or a partner.

Participants valued the qualities of ‘old’ friendships, tied to a life history. This emphasis on long-standing relationships for supporting valued social connections highlights the difficulty of supporting older adults who have, for various reasons, already become socially isolated. Studies of older adults’ social networks have found robust associations between diverse- or friend-focused social networks and the lowest levels of loneliness, which support the participants’ emphasis on seeking out a variety of interest-based social groups (Litwin & Shiovitz-Ezra, 2011). This mosaic of social connections may be disrupted in cases where childhood or adulthood events affected the development of social skills, or where significant past life events disconnected friendships, such as through relocation or conflict (Case et al., 2005; Ejlskov et al., 2020; Hensley et al., 2012). Two participants attributed their past circumstances to having shaped their expectations and coping mechanisms, and thus having better prepared them, mentally and emotionally, for their current life circumstances. However, participants’ discussion of life events primarily centred on past events which were continuing to influence their current circumstances. When participants discussed relocation, they focused on previous networks lost, and social gains from the move centred predominantly on family. This suggests that older adults are less likely to form new friendships, particularly after a loss of old ones. This finding aligns with socioemotional selectivity theory, which suggests that as people age, they refine their social connections, focussing on strengthening existing close relationships and pruning more distant or less rewarding connections (Löckenhoff & Carstensen, 2004). The theory suggests that when people perceive their remaining time as limited, they switch from future-oriented goals seeking novelty, to present-oriented goals seeking emotionally meaningful experiences.

Across the older adult participants’ responses, active and ongoing socialising during earlier life stages emerged almost as an assumed prerequisite to successful socialising in late life. However, the relationship between social isolation and loneliness is not linear, and experience of loneliness has been correlated with childhood and adulthood events even where the individual is not socially isolated in their older age (Ejlskov et al., 2020). According to the loneliness literature, the mediator may be how comfortable individuals feel with their current situation, and how much it matches the expectations that they have for their life. It may be that the participants who highlighted the need to seek out social situations to develop a diverse social network are those who have expectations of maintaining a large social network in old age. For these participants, life events which create discontinuities are likely to instigate loneliness. Conversely, some older adults may be satisfied with a small number of close connections. Across the sample, participants appeared to be highly conscious of their own agency and to feel empowered to make changes in response to perceived deficits in their friendships. Our sample of older adults were all community-dwelling, in affluent suburbs, and so likely were well-resourced to combat loneliness in their own lives. However, with the exception of relocating, they did not discuss taking actions to improve their family relationships.

Regarding family relationships, participants’ loneliness was similarly related to the distinction between desired and actual circumstances. Family relationships have many normative connotations of intrinsic support, care and permanence, and where these were met, participants expressed satisfaction, while where conflict or separation from family members meant that these relationships failed to have these intrinsic qualities, participants expressed dissatisfaction and loneliness. Partnership and its dissolution, through widowhood or divorce, appear as a complex issue in the interviews. While there is a strong body of knowledge that having a partner is protective against loneliness, this is moderated by the quality of the relationship, and is generally stronger for men than for women (Dykstra & de Jong Gierveld, 2004; Shiovitz-Ezra & Leitsch, 2010). These empirical findings are reflected in the interviews, as some participants identified increased loneliness following widowhood due to the loss of a close emotional relationship, but conversely several female participants indicated that marriage had been an unfulfilling or traumatic experience with lasting effects upon their emotional wellbeing and related to subsequent life choices not to repartner.

Stability and continuity of relationships arose as a key factor in prevention of loneliness. This suggests that people’s ability and inclination to make new social connections decreases, or simply that relationships strengthen with time, making longstanding ones more valuable in prevention of loneliness. The value of linked lives across the life course was most represented where participants described loss of these connections, through relocation and geographical distance, bereavement, family estrangement and relationship dissolutions. Furthermore, we can understand the importance of stability through cumulative disadvantage, as losses create the social and emotional context for subsequent difficulties. Participants referred to stable relationships which later provided support, lessening the impact of difficult circumstances, and conversely, discussed how lack of support, through migration and bereavement, increased their difficulties in coping with later negative circumstances.

Our findings are limited to a particular sample of older adults in Australia, and future studies drawing on a larger, more diverse and representative sample could re-examine the findings reported in this chapter. Future research might also examine the relative impact of different life events on later life loneliness and consider a longer span of the life course in relation to later life loneliness. Our findings also suggest the importance of greater knowledge and education on the benefits of maintaining strong social support and ties. Similar to health messaging on exercise and diet, health messaging could alert people to the importance of maintaining social networks and ties to reduce loneliness and increase wellbeing.

References

Aartsen, M., & Jylha, M. (2011). Onset of loneliness in older adults: Results of a 28 year prospective study. European Journal of Ageing, 8, 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0175-7

Andersson, L., & Stevens, N. (1993). Associations between early experiences with parents and well-being in old age. Journal of Gerontology, 48(3), 109–116.

Bishop, A. J., & Martin, P. (2007). The indirect influence of educational attainment on loneliness among unmarried older adults. Educational Gerontology, 33(10), 897–917.

Boger, A., & Huxhold, O. (2020). The changing relationship between partnership status and loneliness: Effects related to aging and historical time. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 75(7), 1423–1432.

Burholt, V., & Scharf, T. (2014). Poor health and loneliness in later life: The role of depressive symptoms, social resources, and rural environments. Journal of Gerontology, Social Sciences, 69(2), 311–324.

Cacioppo, S., Cacioppo, J. T., & Goosens, L. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249.

Case, A., Fertig, A., & Paxson, C. (2005). The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. Journal of Health Economics, 24(2), 365–389.

Cohen-Mansfield, J., Hazan, H., Lerman, Y., & Shalom, V. (2016). Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(4), 557. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1775318646

Dahlberg, L., Andersson, L., McKee, K. J., & Lennartsson, C. (2015). Predictors of loneliness among older women and men in Sweden: A national longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 19(5), 409–417. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13607863.2014.944091

de Koning, J. L., Stathi, A., & Richards, S. (2017). Predictors of loneliness and different types of social isolation of rural-living older adults in the United Kingdom. Ageing and Society, 37(10), 2012–2043.

Dykstra, P. A., & de Jong Gierveld, J. (2004). Gender and marital-history differences in emotional and social loneliness among Dutch older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 23(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1353/cja.2004.0018

Dykstra, P. A., Van Tilburg, T. G., & de Jong Gierveld, J. (2005). Changes in older adult loneliness: Results from a seven-year longitudinal study. Research on Aging, 27(6), 725–747.

Ejlskov, L., Bøggild, H., Kuh, D., & Stafford, M. (2020). Social relationship adversities throughout the lifecourse and risk of loneliness in later life. Ageing and Society, 40(8), 1718–1734. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19000345

Elder, G. H., & Giele, J. Z. (2009). The craft of life course research. Guilford Press.

Fry, P., & Debats, D. (2002). Self-efficacy beliefs as predictors of loneliness and psychological distress in older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 55(3), 233–269.

Gerino, E., Rolle, L., Sechi, C., & Brustia, P. (2017). Loneliness, resilience, mental health, and quality of life in old age: A structural equation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2003.

Hawkley, L., Hughes, M., Waite, L., Masi, C., Thisted, R., & Cacioppo, J. (2008). From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 63(6), S375–S384.

Hensley, B., Martin, P., Margrett, J. A., MacDonald, M., Siegler, I. C., Poon, L. W., & The Georgia Centenarian Study 1. (2012). Life events and personality predicting loneliness among centenarians: Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1–2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.613874

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1745691614568352

Kamiya, Y., Doyle, M., Henretta, J. C., & Timonen, V. (2014). Early-life circumstances and later-life loneliness in Ireland. The Gerontologist, 54(5), 773–783. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt097

Koropeckyj-Cox, T. (1998). Loneliness and depression in middle and old age: Are the childless more vulnerable? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 53(6), S303–S312.

Kung, C. S., Kunz, J. S., & Shields, M. A. (2021). Economic aspects of loneliness in Australia. The Australian Economic Review, 54(1), 147–163.

Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., & Caan, W. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

Lim, M. H., Eres, R., & Vasan, S. (2020). Understanding loneliness in the twenty-first century: An update on correlates, risk factors, and potential solutions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 55(7), 793–810.

Litwin, H., & Shiovitz-Ezra, S. (2011). Social network type and subjective well-being in a national sample of older Americans. The Gerontologist, 51(3), 379–388.

Löckenhoff, C. E., & Carstensen, L. L. (2004). Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1395–1424.

Luchetti, M., Lee, J. H., Aschwanden, D., Sesker, A., Strickhouser, J. E., Terracciano, A., & Sutin, A. R. (2020). The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. American Psychologist, 75(7), 897–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000690

Luo, Y., Hawkley, L. C., Waite, L. J., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2012). Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Social Science & Medicine, 74(6), 907–914.

Merz, E., & de Jong Gierveld, J. (2016). Childhood memories, family ties, sibling support and loneliness in ever-widowed older adults: Quantitative and qualitative results. Ageing and Society, 36, 534–561. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14001329

Newall, N. E., Chipperfield, J. G., & Bailis, D. S. (2014). Predicting stability and change in loneliness in later life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(3), 335–351. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0265407513494951

Nicolaisen, M., & Thorsen, K. (2017). What are friends for? Friendships and loneliness over the lifespan—From 18 to 79 years. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 84(2), 126–158.

Peters, A., & Liefbroer, A. (1997). Beyond marital status: Partner history and well-being in old age. Journal of Marriage and Family, 59(3), 687–699. https://doi.org/10.2307/353954

Pinquart, M., & Sorensen, S. (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245–266. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1207/S15324834BASP2304_2

Rafnsson, S. B., Orrell, M., d’Orsi, E., Hogervorst, E., & Steptoe, A. (2017). Loneliness, social integration, and incident dementia over 6 years: Prospective findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx087

Rico-Uribe, L. A., Caballero, F. F., Martín-María, N., Cabello, M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Miret, M. (2018). Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. PLoS One, 13(1), e0190033. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0190033

Savikko, N., Routasalo, P., Tilvis, R. S., Strandberg, T. E., & Pitkälä, K. H. (2005). Predictors and subjective causes of loneliness in an aged population. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 41(3), 223–233. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0167494305000361#bib16

Schafer, M. H., Shippee, T. P., & Ferraro, K. F. (2009). When does disadvantage not accumulate? Toward a sociological conceptualization of resilience. Schweizerische Zeitschrift fur Soziologie. Revue suisse de sociologie, 35(2), 231.

Shiovitz-Ezra, S., & Leitsch, S. (2010). The role of social relationships in predicting loneliness: The national social life, health, and aging project. Social Work Research, 34(3), 157–167. Retrieved 15 July 2020 from www.jstor.org/stable/42659760

Steed, L., Boldy, D., Grenade, L., & Iredell, H. (2007). The demographics of loneliness among older people in Perth, Western Australia. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 26(2), 81–86. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2007.00221.x

Timonen, V., & Doyle, M. (2014). Life-long singlehood: Intersections of the past and the present. Ageing and Society, 34(10), 1749–1770. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000500

Van Humbeeck, L., Dillen, L., Piers, R., Grypdonck, M., & van den Noortgate, N. (2016). The suffering in silence of older parents whose child died of cancer: A qualitative study. Death Studies, 40(10), 607–617. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/07481187.2016.1198942

van Tilburg, T., Steinmetz, S., Stolte, E., van der Roest, H., & de Vries, D. (2020). Loneliness and mental health during the COVID 19 pandemic: A study among Dutch older adults. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(7), e249–e255. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa111

Victor, C. R., & Bowling, A. (2012). A longitudinal analysis of loneliness among older people in Great Britain. The Journal of Psychology, 146(3), 313–331. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00223980.2011.609572?src=recsys

von Soest, T., Luhmann, M., Hansen, T., & Gerstorf, D. (2018). Development of loneliness in midlife and old age: Its nature and correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2018-49054-001.pdf

Wenger, G. C., & Burholt, V. (2004). Changes in levels of social isolation and loneliness among older people in a rural area: A twenty–year longitudinal study. Canadian Journal on Aging/la revue canadienne du vieillissement, 23(2), 115–127.

Wu, Z., & Penning, M. (2015). Immigration and loneliness in later life. Ageing and Society, 35(1), 64–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000470

Zoutewelle-Terovan, M., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2018). Swimming against the stream: Non-normative family transitions and loneliness in later life across 12 nations. The Gerontologist, 58(6), 1096–1108. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx184

Acknowledgements

We are especially grateful for the time of the research participants for speaking with us as well as the support for recruitment from the home care organisation. We would also like to acknowledge the support of the research assistants who took part in this project, for assistance with recruitment, data collection and analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lam, J., Dickson, C., Baxter, J. (2022). Ageing and Loneliness: A Life Course and Cumulative Disadvantage Approach. In: Baxter, J., Lam, J., Povey, J., Lee, R., Zubrick, S.R. (eds) Family Dynamics over the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-12223-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-12224-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)