Abstract

Married couples generally experience higher levels of subjective wellbeing than cohabiting couples or single people, though the relationship between wellbeing and partnering is context-specific. Marriage has different benefits for different demographic and subgroups and varies by gender, nativity, birth region, and country contexts. We find that across several measures of socioeconomic wellbeing, married individuals show better outcomes than their cohabiting counterparts and single individuals. Married individuals are more likely to be employed, own a home, and have access to emergency funds, net of various socioeconomic and demographic controls. These advantages remain even when we consider their outcomes after they have transitioned to marriage controlling for unobserved and observed bias. We find no substantive differences in health and wellbeing across individuals of different marital statuses. We conclude that policies aimed at supporting individuals to achieve fulfilling lives must recognise increased diversity in partnership arrangements and provide strong supports to those who choose not to pursue traditional marital arrangements.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

There have been numerous changes in marriage and cohabiting patterns in Australia over the last few decades signaling shifts in the meaning and place of marriage in the life course. Marriage remains a relevant milestone for Australians with most still marrying, but how, why and when marriage takes place has changed markedly (Qu, 2020). As is the case for other western countries, the crude marriage rate in Australia (marriages per 1000 head of population) has declined steadily since the 1970s from over 9% in 1970 to 4.5% in 2019 (Baxter et al., 2015; ABS, 2019a). In 1981, over 80% of individuals aged 40–44 were married while in 2016 the comparable figure was only 60% (Qu, 2020). Single-parent families currently comprise about 12% of family households, with single-male-parent households projected to be the fastest growing family type over coming decades (ABS, 2019b).

How people marry has also changed with only about 20% of marriages in Australia in 2020 performed by a minister of religion, down from 70% in the 1970s. This signals not only a decline in religiosity but also changing views about the role of religion in endorsing personal relationships (Qu, 2020). At the same time, unmarried cohabitation has become much more common, both as a precursor to marriage and as an alternative. In Australia, the percentage of people cohabiting was almost 20% in 2016 compared with only 5% in 1986 (Qu, 2020). While cohabitation is more common among younger individuals, it has increased across all age groups in Australia. Overall, aggregate trends suggest that cohabitation is becoming a more important and permanent means of partnering in Australia. Views on marriage have also changed with about 29% of people who participated in the Australia Talks National Survey (Zhou, 2021) reporting marriage is an outdated institution, with a higher proportion of women (33%) feeling this way compared to men (24%) and a much higher proportion of younger women aged 18–39 years feeling this way (43%) compared to older women over age 75 (13%) (Zhou, 2021).

These figures portray important changes in the ways Australians think about and organise their personal and family lives. They also have important implications for understanding patterns of disadvantage in families. In general, marriage has long been associated with social advantage, conferred status, and economic security (Sassler & Schoen, 1999; Smock et al., 1999). Single-parent households are consistently found to be amongst the most vulnerable in Australia in terms of poverty, housing insecurity and reliance on income support (Wilkins et al. 2020). There is evidence to suggest that those with higher socioeconomic positions are more likely to marry while those with lower socioeconomic positions are more likely to cohabit (Carlson et al., 2004; Baxter et al., 2015; Perelli-Harris et al., 2019). The relationship between marriage and social advantage likely reflects a combination of causal and selection effects with marriage both leading to economic advantage and those with economic advantage more likely to marry.

In this chapter we examine marriage, cohabitation and singlehood in the Australian context with a focus on how partnering is related to variations in social disadvantage and wellbeing for men and women. First, we discuss recent theories that explain the changing place of marriage in life course trajectories. We also review evidence on who gets married, who cohabits or remains single and their associated outcomes. Second, we utilize longitudinal data that enables us to examine, within individuals, how marriage and cohabitation affect outcomes relating to social disadvantage and wellbeing. Third, we discuss implications for life course theories, current understandings of partnering and family relationships and policy implications.

Marriage as a Foundation or Capstone?

Cherlin (2004, 2009) has argued that trends over the last few decades suggest that marriage is undergoing a process of deinstitutionalization where there is a weakening of the norms and behaviour patterns that characterise marriage. The emergence of new forms of family, such as cohabitation, the increase in age at first marriage, increasing numbers remaining single, the rise of childbearing outside marriage, and increase in divorce all suggest that marriage is optional, and that those who marry and stay married are unusual. As laws have changed to enable alternatives to marriage and new forms of partnering have become more socially acceptable, marriage may have lost its practical and social significance. Legislation also increasingly recognises and protects shared financial, family and estate contributions for both partners, and particularly women, if the relationship should end, enabling financially viable pathways out of unhappy relationships. In Australia, alternative partnering options include registered partnerships which provide cohabiting couples with many of the same legal arrangements as traditional marriage and same-sex marriage which became legal in 2017.

Marriage was traditionally a springboard to adulthood, a life course event that indicated the beginning of adulthood entailing leaving the family of origin home, setting up a new household, economic independence, employment and start of parenthood (Marini, 1978). However, as discussed in Chap. 8 in relation to emerging adulthood, young people are increasingly delaying marriage, perhaps due to the difficulty in attaining social and financial independence. Increasingly, marriage is associated with a certain level of financial stability and those with fewer financial resources and less stable employment are more likely to delay marriage (Edin, 2000; Aldo, 2014). As a result, marriage has shifted from a springboard into adulthood to a capstone that must now wait until several milestones have already been achieved (Cherlin, 2004; Edin & Kefalas, 2005; Holland, 2013). If true, this has implications for both the meaning and returns to marriage. In particular, those who are the most disadvantaged may not be able to reach this capstone making it a desirable but unachievable life course event.

One implication of the deinstitutionalization of marriage and its shift to a capstone event is that some of the social and psychological gains of belonging to a well-recognized and established institution are also diminishing. As cohabitation becomes more widespread and institutionalised, it may, in turn, produce similar social and psychological benefits as marriage. Research has identified several advantages associated with marriage. Married individuals have reported greater subjective wellbeing, mental and physical health (Waite & Gallagher, 2000), and economic resources (Sassler & Lichter, 2020). Given that cohabitation is increasingly similar in form and function to marriage, it is possible that these benefits may now extend to those who cohabit (Musick & Bumpass, 2012). There are several similarities between cohabitation and marriage. Cohabitating unions mark the start of coresidential partnerships and also increasingly represent settings for having and raising children (Perelli-Harris & Sanchez Gassen, 2012). As cohabitation becomes more widely accepted, it is possible that we are witnessing a convergence of the benefits of marriage and cohabitation (Sassler & Lichter, 2020).

Nonetheless, there are some important differences between marriage and cohabitation that may lead marriage to retain distinct benefits. Cohabitation may represent a less stable family type, even among those who have children (Andersson et al., 2017; Musick & Michelmore, 2018). This may negatively affect wellbeing with cohabitors more likely to have lower life satisfaction (Soons & Kalmijn, 2009) lower relationship quality (Wiik et al., 2012), higher levels of depression (Brown, 2000; Lamb et al., 2003), and worse health (Musick & Bumpass, 2012). In general, it may be that cohabitation is associated with a pattern of disadvantage that continues across the life course, including less stable relationships, less financial security, higher unemployment, and lower wellbeing.

Who Marries and Who Cohabits?

One reason why the benefits to marriage may differ is because cohabiting couples and married couples differ in their composition. Though this has changed over time, cohabitation has been previously more common amongst those with lower economic resources or educational attainment (Heard, 2011; Evans, 2015). In Australia, individuals with higher education levels are more likely to marry than those with lower education (Hewitt & Baxter, 2011; Evans, 2015; Heard, 2011).

Much of our understanding of the link between marital patterns and social disadvantage is based on the United States which varies from Australia in several key ways that are related to marital patterns and social disadvantage. Although the United States and Australia are often considered liberal welfare states with a limited safety net and reliance on means-tested benefits, Australia offers more universal benefits overall (Arts & Gelissen, 2002; Esping-Andersen, 1990). In turn, women in Australia may be less dependent on marriage for financial security. Furthermore, married and cohabiting couples in Australia share many of the same rights and this is much less true in the United States (Perrelli-Harris et al., 2018). For instance, in Australia, cohabitors share similar access to family courts in the event of union dissolution and similar rights to inheritance (Evans, 2015). Overall, Australia provides greater state support for cohabiting couples than the United States, which may reflect the general acceptance of cohabitation and in turn, lower incentives for marriage. Moreover, there is a strong link between cohabitation and disadvantage observed in the United States in a way that is not the case in Australia (Perelli-Harris & Lyons-Amos, 2016). Therefore, it is possible that the strong links between marital patterns and social disadvantage are more characteristic of US society than Australian society. To examine these issues and to provide an overview of the associations between different forms of partnering and social disadvantage, we address the following questions in this chapter:

-

1.

What are the characteristics of individuals who marry and are there differences with those who cohabit in Australia?

-

2.

Is partnership status associated with variations in social disadvantage and wellbeing?

-

3.

Are observed variations explained by selection of individuals with certain characteristics into partnerships or do partnerships lead to variations in outcomes?

Results

Who Marries and Who Cohabits in Australia? Evidence from HILDA

To answer these questions, we use data from The Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, waves 1–18. To address our first two research questions, we examine three groups of individuals: individuals who are singleFootnote 1 (never married and not living with a partner but could be partnered) throughout the 18 waves of the survey (n = 38,330); individuals who move from single to cohabiting (never married and living with partner) (n = 19,966); and those who transition from single to married (n = 189,39).Footnote 2 We restrict our sample to men and women who were single in their first wave of the survey so that we can observe the effects of the transitions to partnership on various outcome measures. We use multinomial logistic regression to predict whether individuals transition from single to cohabitation, single to married, or stay single (reference category) and to examine the characteristics of those who make these different transitions.

This approach allows us to extend the existing literature by examining the outcomes of those who stay single along with those who transition to cohabitation and marriage. While most previous research has compared outcomes for the latter two groups of partnered individuals, we widen our lens to include single individuals as a way of understanding the broader effects of marital status and coresident partnerships. By including singles as a reference category, we can compare outcomes for those who cohabit and marry as well as make comparisons between coresident partnerships and other individuals. Additionally, given our interest in the relationship between marital status and social disadvantage, including single individuals expands the depth of our knowledge.

We include several independent variables in our model: gender, racial/ethnic background (Indigenous Australian, English Speaking Background Immigrant, Non-English Speaking Background Immigrant, and non-Indigenous Australian educational attainment (high school degree, diploma or certificate, Bachelor’s degree, graduate/postgraduate degree, and less than high school), individual income, age, labour force status (unemployed, not in the labour force, and employed), remoteness (inner regional Australia, outer regional Australia, and major city), presence of children (age 14 or less) in the home, and survey wave.

Figures 10.1 and 10.2 present the predicted probabilities of being in each marital status by racial and ethnic background for women and men, respectively. The predicted probabilities are based on the regression model with independent variables held constant at their means. Taken together, both Figs. 10.1 and 10.2 show that across all racial/ethnic groups, about half stay single over their duration in the survey. Among those who partner, women and men who are Indigenous Australians and immigrants from English-Speaking Backgrounds show a greater probability of cohabitating than marrying. In contrast, immigrants from non-English speaking backgrounds show a greater probability of marriage. Thus, we see that despite being foreign-born, immigrant background influences partnership pathways.

Marital status by race/ethnicity for women.

Note: Predicted probabilities of marital status are based on regression analysis controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, personal income, age, labour force status, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Marital status by race/ethnicity for men.

Note: Predicted probabilities of marital status are based on regression analysis controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, personal income, age, labour force status, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Additionally, when we compare how the relationship between marital status and racial and ethnic background differs by gender, we find that relative to their female counterparts in each racial/ethnic group, men show higher probabilities of staying single, but lower probabilities of cohabiting across each group. Men and women show similar probabilities of marriage by racial/ethnic group. For instance, among non-Indigenous native-born Australians, we find that relative to men, women are less likely to be single (0.47 versus 0.52), more likely to cohabit (0.28 versus 0.24), and less likely to marry (0.25 versus 0.24). This suggests that among men, staying single is the most common but for those who do partner, they are slightly more likely to marry. In contrast, women are more likely to transition into cohabitation.

Both men and women with Indigenous backgrounds show the highest probabilities of being single or cohabiting and immigrants from non-English speaking backgrounds show the highest probabilities of marriage. Overall, Figs. 10.1 and 10.2 show large racial and ethnic differences in the probability of staying single, transitioning to cohabitation, and transitioning to marriage. We find that the racial and ethnic variation across marital status is consistent for men and women despite men showing higher probabilities of staying single and smaller probabilities of cohabitation.

We also examine how marital status differs by education level and gender. Figure 10.3 presents the predicted probabilities of marital status for those with a high school degree and bachelor’s degree or higher by gender. For both men and women, we find that those with a high school degree show the highest probabilities of staying single though this is slightly higher for men (0.47 versus 0.51). Moreover, the likelihood of cohabitation is also higher among women and men with a high school degree (0.28 versus 0.24). Men and women with at least a Bachelor’s degree show the highest probabilities of marriage (0.36 versus 0.37). Overall, Fig. 10.3 shows that education is positively associated with marital status where those with higher levels of education are more likely to marry whereas those with lower education levels are more likely to stay single or cohabit.

Marital status by education level and gender.

Note: Predicted probabilities of marital status are based on regression analysis controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, personal income, age, labour force status, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Figure 10.4 also presents the predicted probabilities of marital status by labour force status and gender. In general, we see some variation in employment across marital status particularly when we focus on the role of unemployment and not in labour force in predicting marital status. Figure 10.4 shows that single men and women have the highest probabilities of unemployment (53.3 and 58.3) and not being in the labour force (54.8 and 59.6) respectively. In contrast, women and men who transition to marriage (15.4 and 14.8) or transition to cohabitation (31.3 and 27) have lower probabilities of unemployment respectively. Thus, this indicates that those who are unemployed or not in the labour force are more likely to be single or cohabitating relative to married individuals.

Marital status by labour force status and gender.

Note: Predicted probabilities of marital status are based on regression analyses controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, personal income, age, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Taken together, the findings thus far illustrate the role of racial and ethnic background, educational attainment, and labour force status on the probability of staying single, transitioning to cohabitation, or transitioning to marriage. Overall, those who marry are the least disadvantaged while those who remain single appear to be the most disadvantaged with cohabitors somewhere in between. Understanding why Indigenous Australians and English Speaking Background immigrants have higher probabilities of cohabitation whereas Non-English Speaking Background immigrants show higher probabilities of marriage has important implications for social disadvantage. These differences may be linked to cultural variations in the importance of marriage and family or may stem from compositional differences in the socio-economic characteristics of Indigenous and NESB groups.

Is Partnership Status Associated with Variations in Social Disadvantage and Wellbeing?

A second aim of this chapter is to examine the relationship between marital status and social disadvantage by observing how single, cohabiting, and married individuals differ along several health, wellbeing, and socioeconomic indicators. Our analyses will show descriptively how individuals across the three marital statuses compare in their health and wellbeing and socioeconomic status. We exploit the longitudinal feature of HILDA data to examine, within individuals, how marriage and cohabitation affects outcomes relating to wellbeing and disadvantage.

Subjective Wellbeing

Several studies have found that married individuals have higher levels of subjective wellbeing than non-married individuals (Mikucka, 2016; Stutzer & Frey, 2004; Waite & Gallagher, 2000), including cohabiting couples (Waite & Gallagher, 2000). Perelli-Harris et al. (2019) and Wilkins et al. (2020) find that married men and women in Australia have higher subjective wellbeing scores than those who are cohabiting, separated, divorced, widowed, or never married. Similarly, married individuals report greater satisfaction with all aspects of employment, finances, housing, safety, and leisure (Wilkins et al., 2020).

We add to this body of work by showing descriptively the long-term mental health outcomes of those who stay single, those who transition from single to cohabiting, and those who transition from single to married in Australia. Figures 10.5 and 10.6 show the predicted mental health scores by marital status over time for women and men, respectively, with independent variables held constant at their means. The predicted probabilities are based on random-effect linear regression models predicting mental health scores controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, individual income, age, labour force status, presence of young children, and survey wave. We measure mental health using the Mental Component Summary (MCS) score, which is drawn from a patient-reported Short Form 36 (SF-36) (Butterworth & Crosier, 2004). It is created from several subscales measuring mental health, emotional problems, and social functioning. The scale ranges between 0 and 100 with a higher score representing better mental health. In Figs. 10.4 and 10.5, higher predicted scores on the vertical axis indicate better self-assessed mental health.

Predicted mental health scores for women by marital status over survey wave.

Note: Predicted probabilities of mental health scores are based on random-effect linear regression analysis controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, personal income, age, labour force status, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Predicted mental health scores for men by marital status over survey wave.

Note: Predicted probabilities of mental health scores are based on random-effect linear regression analysis controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, personal income, age, labour force status, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Figures 10.5 and 10.6 show that across all marital status groups, mental health scores decline over time for both men and women. Nonetheless, we find that those who transitioned from single to married consistently show the highest mental health scores, followed by those who transitioned from single to cohabiting and those who remain single. We find that these patterns hold for both men and women, though men in each marital status show better mental health scores than their female counterparts. This indicates a selection effect with men and women with better mental health more likely to select into marriage than either cohabitation or remaining single.

Additionally, Figs. 10.5 and 10.6 show that men have better mental health scores than women. Specifically, married men report the highest mental health scores as indicated on the top line in Fig. 10.6 and single women report the lowest scores as indicated by the bottom line in Fig. 10.5. In fact, the mental health of married women is roughly equivalent to that of single men. This supports arguments showing that men experience a “marriage premium” though this has typically focused on the effects of marriage on men’s labour market outcomes (Cohen, 2009). To sum up, Figs. 10.5 and 10.6 show that net of controls, individuals who transition to marriage consistently show the greatest predicted mental health scores, especially men, whereas those who remain unpartnered show the lowest predicted mental health scores, with unpartnered women being particularly vulnerable to poor mental health. Likewise, we find that people transitioning to marriage also start with greater mental health as indicated by their higher mental health scores, which suggests a likely selection effect in which those with greater health are more likely to select into marriage.

Economic Wellbeing

Another possible benefit of marriage is greater financial security and economic wellbeing (Hardy & Lucas, 2010; Sweeney, 2002). Married individuals are more likely to pool and jointly manage their resources than cohabiting partners (Brines & Joyner, 1999; Treas & De Ruijter, 2008). Cohabitation is not associated with the same norms of sharing finances suggesting divergent patterns in how married and cohabiting individuals organise their relationships (Hardy & Lucas, 2010). In Australia, married individuals have higher household incomes than cohabiting individuals. Perrelli-Harris report that around 26% of married men were in the highest household income quintile compared with only 11% of cohabiting men in 2013 (Perrelli-Harris et al., 2019). Additionally, in the same year, nearly 18% of cohabiting men were in the lowest income quintile compared to 8% of married men (Perrelli-Harris et al., 2019).

We measure economic wellbeing using two indicators: access to emergency funds and employment. We measure access to emergency funds as a dichotomous variable with no access to emergency funds as the reference category. These are derived from several questions in the HILDA survey asking respondents how difficult it would be to raise $2000 for an emergency (“easily”; “with some sacrifices”; “would have to do something drastic”; or “couldn’t raise emergency funds”). We measure employment as a dichotomous variable capturing employed versus unemployed/not in the labour force. This is derived from annual survey questions about current labour force status (employed, unemployed, or not in the labour force).

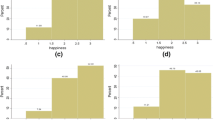

Figures 10.7 and 10.8 show the predicted probability of access to emergency funds for women and men respectively. A higher value on the vertical axis indicates a higher probability of access to emergency funds. The predicted probabilities are based on random-effect logistic regression models predicting access to emergency funds or not, controlling for gender, racial/ethnic background, educational attainment, individual income, age, labour force status, presence of young children, and survey wave. Overall, Figs. 10.7 and 10.8 show that men and women of all partnership statuses develop greater financial security over time. Likewise, both men and women who transitioned from single to marriage show the highest probability of financial wellbeing, followed by individuals who transitioned from single to cohabiting and single individuals. However, men show larger disparities in access to financial wellbeing by marital status than their female counterparts, suggesting a larger association between whether men transition to cohabitation or marriage and their access to emergency funds over time. This gender disparity may be shaped by our subjective measure of financial wellbeing, rather than an objective measure. Related, it is possible that men may feel a greater need to reach a certain level of financial wellbeing before transitioning to partnership.

Predicted probability of access to emergency funds for women by marital status over survey wave.

Note: Predicted probabilities of access to emergency funds are based on random-effect linear regression analysis controlling for gender, educational attainment, personal income, age, labour force status, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Predicted probability of access to emergency funds for men by marital status over survey wave.

Note: Predicted probabilities of access to emergency funds are based on random-effect linear regression analysis controlling for gender, educational attainment, personal income, age, labour force status, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

We also consider the relationship between marital status and employment for men and women (figures not shown). Not surprisingly, we find that men’s employment probability is higher than their female counterparts. Even among those who stay single, men consistently show higher employment probabilities than their female counterparts. For both men and women, the probability of employment slightly increases over time but it remains relatively flat. Again, we see that employment probabilities differ with those who transitioned to marriage showing the highest probabilities, followed by those who transitioned to cohabitation, and single individuals showing the lowest probabilities. We see the same pattern for women and men though again, the gaps in employment by marital status are larger for men.

In sum, our analyses show that, those who transition from single to married show the strongest mental health and financial wellbeing, net of controls. Additionally, we find that those who do not partner show the worst outcomes across these indicators. We find that these differences persist over time and are consistent for men and women, though men have higher wellbeing, employment, and financial security than women.

Is Marriage Selective or Protective?

Central to the discussion about the positive association between marriage and social advantage is whether the effect is causal or selective (Osborne et al., 2007; Perelli-Harris et al., 2019). In other words, is the greater subjective and economic wellbeing observed among married individuals an effect of marriage or is it explained by the advantages that select individuals into marriage (Stutzer & Frey, 2004)? Relatedly, are the poorer outcomes observed among cohabiting individuals an effect of cohabitation or a result of cohabitation being selective of disadvantage (Kennedy & Bumpass, 2008; McLanahan & Percheski, 2008; Perelli Harris et al., 2018)?

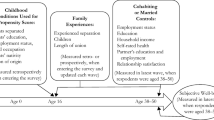

While it is beyond the scope of this chapter to establish causality, we contribute by observing whether there are differences in subjective wellbeing and self-rated health, financial stability, home ownership, and employment by marital status. We include two additional measures—self-rated health and homeownership—to broaden our understanding of the relationship between marital status and social disadvantage. We include self-rated health which is known to be a valid measure of physical health (Noymer & Lee, 2012). In addition, we include homeownership as it is viewed as an indicator of material wellbeing and is an important source of wealth accumulation in Australia, but also central for promoting equality of opportunity (Kuebler & Rugh, 2013; Lewin-Epstein & Semyonov, 2000). Home ownership is measured as a dichotomous variable capturing whether individuals own their home or not (reference category). This is derived from an annual question in HILDA where respondents are asked about their housing status (own their home, rent it, or live rent free).

Using the longitudinal feature of the HILDA data, we examine how these various wellbeing, health, and socioeconomic outcomes vary among individuals who are single, cohabiting, and married. We used fixed effects models to account for within-individual transitions in marital status and the subsequent effects on each of the outcome variables. Fixed effects models allow us to address possible selection bias in which more advantaged individuals are more likely to select into marriage. Fixed effects models eliminate between-person variation that may confound the relationship between marital status and wellbeing and socioeconomic outcomes (Allison, 2009; Wooldridge, 2010). In turn, these models account for within-person changes in outcomes so respondents are compared to their own averages over the event of a move into cohabitation or marriage and thus, controls for some observed and unobserved factors.

In Figs. 10.9 and 10.10, we present the predicted health and socioeconomic outcomes across three marital statuses, for women and men respectively. We focus first on self-rated health, which ranges from 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating better health. This is derived from a question asking survey respondents to rank their health as “poor”, “fair”, “good”, “very good”, and “excellent”. A higher value on the vertical axis indicates greater self-rated health.

Wellbeing and socioeconomic outcomes after transition to partnership, by marital status for women.

Note: Predicted probabilities based on fixed effect regression analysis controlling for marital status, educational attainment, personal income, age, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Predicted wellbeing and socioeconomic outcomes by marital status for men.

Notes: Predicted probabilities based on fixed effect regression analysis controlling for marital status, educational attainment, personal income, age, remoteness, presence of young children in the home, and survey wave. (Source: Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey, Waves 1–18)

Figure 10.9 shows virtually no differences across the groups of women in relation to health or employment. On the other hand, when we examine homeownership, we find that about 74% of married women own a home compared with only 66.4% of single women and 57.4% of cohabiting women. Figure 10.9 also shows married women have much greater access to emergency funds (60.5%) than cohabiting (53.6%) and single (47.1%) women. We also show the wellbeing and socioeconomic outcomes by marital status among men in Fig. 10.10. Here we see similar patterns. Amongst men, there are no substantive differences in self-rated health or mental health across the groups. But like women, married men are much more likely than cohabiting and single men to own their own home and to have access to emergency funds.

Interestingly, we find that cohabitors have a lower probability of home ownership than their married or single counterparts. This suggests that home ownership may represent an important milestone or step for cohabiting individuals that influences whether they transition to marriage. Finally, the results also show a clear gap between married and non-married individuals in access to emergency funds. Single (56.6%) and cohabiting (60.7%) individuals show much lower financial security in this regard relative to married individuals (64%). This indicates that financial security may be an important milestone that individuals or couples achieve before transitioning to marriage.

Taken together, Figs. 10.9 and 10.10 illustrate disparities across marital status depend on the specific outcome. We find that married men and women have greater financial stability relative to cohabiting and single individuals, a result that is consistent with previous studies (Lee & Ono, 2012). We find no differences in relation to health. We also find some gender differences in how marital status shapes employment. In particular, we find that partnership increases the likelihood of employment among men whereas we find the opposite for women, although the differences for women are small. Specifically, partnered women show slightly lower employment than single women whereas partnered men show higher employment than single men. For women these patterns are consistent with persisting gender divisions of labour in households where women do more unpaid care and domestic work than men. Australia still largely conforms to traditional gender roles with men serving as breadwinners and women taking up greater unpaid care and domestic work (Baxter et al., 2008; Baxter & Tai, 2016). Overall, our results show that even after controlling for selection, we find that married individuals show greater socioeconomic outcomes indicating that selection alone is unlikely to explain these outcomes observed among married individuals.

Discussion

Partnership transitions are important life course events that influence wellbeing and disadvantage outcomes. On average, individuals who do not transition to marriage fare worse than those who do on a number of the indicators considered here. Overall, we find that across several measures of socioeconomic wellbeing, married individuals show better outcomes than their cohabiting counterparts and single individuals. Married individuals are more likely to be employed, own a home, and have access to emergency funds, net of various socioeconomic and demographic controls. Additionally, these advantages remain even when we consider their outcomes after they have transitioned to marriage controlling for unobserved and observed bias. While it is beyond the scope of this study to determine whether such differences are due to selection or the returns to partnership, it is clear that cohabiting individuals are more socioeconomically disadvantaged than their married counterparts and single individuals are the most disadvantaged. In sum, our findings suggest that the socioeconomic advantages incurred by married individuals is unlikely to reflect selection alone. We find no substantive differences in health and wellbeing across individuals of different marital statuses and no evidence that marriage is associated with greater subjective wellbeing or health. An avenue for future research may be to consider why marriage provides greater socioeconomic benefits relative to cohabiting and single individuals but not the same benefits for subjective wellbeing and health.

Across gender, nativity, and Indigenous background, we find a strong association between marriage and social advantage and similarly, strong associations between being single and social disadvantage. Across all groups, we find that married individuals continue to show greater socioeconomic outcomes, health, and wellbeing. However, we find that the gap between married and cohabiting individuals varies by gender, nativity, and Indigenous backgrounds. This lends support to the idea that selection into marriage, cohabitation, or staying single varies by subgroup. Similarly, this may reflect variation in the meanings attached to marriage and cohabitation and differences in whether groups view cohabitation as a stepping stone or a final partnership destination. Future work may consider how group membership alters our understanding of marriage, cohabitation, and being single. It is possible that the meaning of marriage or the acceptance of cohabitation may vary by subgroup in complex ways. Additionally, it is clear that the effects of cohabitation may lead to greater benefits for some outcomes but not others. Therefore, greater research in understanding where cohabitation acts as a proxy for marriage and where it provides similar outcomes to those who are unpartnered can extend our knowledge on the unique benefits of marriage.

Conclusion

Marriage patterns have changed over time and there is considerable evidence that Cherlin (2004) is correct in arguing that marriage is now more effectively viewed as a capstone life course achievement rather than a springboard into adulthood. Policies aimed at supporting individuals to achieve fulfilling lives must recognise increased diversity in partnership arrangements and provide strong supports to those who choose not to pursue traditional marital arrangements. In this chapter, we show that individuals who do not partner have the greatest disadvantage and this is exacerbated for single women. Whether single individuals have disadvantages that preclude their opportunities for partnership or whether their disadvantages accrue by not partnering, our findings show that their longstanding disadvantages in the labour market and limited financial stability suggest greater needs for social and economic support. This suggests a clear need for policy supports that focus on single individuals, especially single women and parents.

We also find those who cohabit show greater disadvantages across several outcomes relative to their married counterparts. In some cases, cohabiting individuals show only slightly better outcomes than single individuals. This highlights the need for policies that focus on unmarried individuals. Tailored policy approaches are required as policies for all unmarried individuals do not focus specifically on the challenges facing single individuals. Likewise, among single individuals, women are particularly disadvantaged and need additional resources to address their specific challenges.

Notes

- 1.

It is not possible in HILDA to distinguish between individuals who are unpartnered from individuals who are partnered and not living together. It is likely that some of the respondents are in relationships as 22% report having children under 14.

- 2.

Individuals who transitioned from single to married do not include those who were previously cohabiting. In our analyses, we drop individuals who moved from single to cohabiting to marriage to isolate the effects of moving from single to cohabiting only and single to married only.

References

Aldo, F. R. (2014). Debt, cohabitation, and marriage in young adulthood. Demography, 51, 1677–1701.

Allison, P. D. (2009). Fixed effects regression models. Sage.

Andersson, G., Thomson, E., & Duntava, A. (2017). Life-table representations of family dynamics in the 21st century. Demographic Research, 37(35), 1081–1230.

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. Journal of European Social Policy, 12(2), 137–158.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019a). Marriages and divorces, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/marriages-and-divorces-australia/latest-release#data-download

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2019b). Household and family projections, Australia, 2016 to 2041. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/household-and-family-projections-australia/latest-release

Baxter, J., & Tai, T. (2016). Unpaid domestic labour. In S. Edgell, H. Gottfried, & E. Granter (Eds.), Sage handbook of the sociology of work and employment (pp. 444–465). Sage.

Baxter, J., Hewitt, B., & Haynes, M. (2008). Life course transitions and housework: Marriage, parenthood and time on housework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 259–272.

Baxter, J., Hewitt, B., & Rose, J. (2015). Marriage. In G. Heard & D. Arunachalam (Eds.), Family formation in the 21st century Australia (pp. 31–51). Springer.

Brines, J., & Joyner, K. (1999). The ties that bind: Principles of cohesion in cohabitation and marriage. American Sociological Review, 64(3), 333–355.

Brown, S. L. (2000). The effect of union type on psychological well-being: Depression among cohabitors versus marrieds. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(3), 241–255.

Butterworth, P., & Crosier, T. (2004). The validity of the SF-36 in an Australian National Household Survey: Demonstrating the applicability of the household income and labour dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey to examination of health inequalities. BMC Public Health, 4(44), 1–11.

Carlson, M., Mclanahan, S., & England, P. (2004). Union formation in fragile families. Demography, 41(2), 237–261.

Cherlin, A. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66, 848–861.

Cherlin, A. (2009). The marriage-go-round. The state of marriage and the family in America today. Alfred Knopf.

Cohen, P. N. (2009). Racial-ethnic and gender differences in returns to cohabitation and marriage: Evidence from the current population survey (Population Division Working Paper, No.35) (pp. 1–11). U.S. Bureau of the Census.

Edin, K. (2000). What do low-income single mothers say about marriage? Social Problems, 47(1), 112–133.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. University of California Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). Three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Evans, A. (2015). Entering a union in the twenty-first century: Cohabitation and ‘living apart together’. In G. Heard & D. Arunachalam (Eds.), Family formation in the 21st century Australia. Springer.

Hardy, J. H., & Lucas, A. (2010). Economic factors and relationship quality among young couples: Comparing cohabitation and marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1141–1154.

Heard, G. (2011). Socioeconomic marriage differentials in Australia and New Zealand. Population and Development Review, 37(1), 125–160.

Hewitt, B., & Baxter, J. (2011). Who gets married in Australia? The economic and social determinants of a transition into first marriage 2001–2006. Journal of Sociology, 48(1), 43–61.

Holland, J. A. (2013). Love, marriage, then the baby carriage? Marriage timing and childbearing in Sweden. Demographic Research, 29, 275–306.

Kennedy, S., & Bumpass, L. L. (2008). Cohabitation and children’s living arrangements: New estimates from the United States. Demographic Research, 19, 1663–1692.

Kuebler, M., & Rugh, J. S. (2013). New evidence on racial and ethnic disparities in homeownership in the United States from 2001 to 2010. Social Science Research, 42, 1357–1374.

Lamb, K. A., Lee, G. R., & DeMaris, A. (2003). Union formation and depression: Selection and relationship effects. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(4), 953–962.

Lee, K. S., & Ono, H. (2012). Marriage, cohabitation, and happiness: A cross-national analysis of 27 countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 953–972.

Lewin-Epstein, N., & Semyonov, M. (2000). Migration, ethnicity, and inequality: Homeownership in Israel. Social Problems, 47(3), 425–444.

Marini, M. M. (1978). The transition to adulthood: Sex differences in educational attainment and age at marriage. American Sociological Review, 43(4), 483–507.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

Mikucka, M. (2016). The life satisfaction advantage of being married and gender specialization. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 759–779.

Musick, K., & Bumpass, L. (2012). Reexamining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in wellbeing. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 1–18.

Musick, K., & Michelmore, K. (2018). Cross-national comparisons of union stability in cohabiting and married families with children. Demography, 55, 1389–1421.

Noymer, A., & Lee, R. (2012). Immigrant health around the world: Evidence from the world values survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15, 614–623.

Osborne, C., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2007). Married and cohabiting parents’ relationship stability: A focus on race and ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(5), 1345–1366.

Perelli-Harris, B., & Lyons-Amos, M. (2016). Partnership patterns in the United States and across Europe: The role of education and country context. Social Forces, 95(1), 251–282.

Perelli-Harris, B., & Sánchez Gassen, N. (2012). How similar are cohabitation and marriage? Legal approaches to cohabitation across Western Europe. Population and Development Review, 38(3), 435–467.

Perelli-Harris, B., Hoherz, S., Addo, F., Lappegård, T., Evans, A., Sassler, S., & Styre, M. (2018). Do marriage and cohabitation provide benefits to health in mid-life? The role of childhood selection mechanism and partnership characteristics across countries. Population Research and Policy Review, 37, 703–728.

Perelli-Harris, B., Hoherz, S., Lappegård, T., & Evans, A. (2019). Mind the “happiness” gap: The relationship between cohabitation, marriage, and subjective well-being in the United Kingdom, Australia, Germany, and Norway. Demography, 56, 1219–1246.

Qu, L. (2020). Couple relationships. Australian Institute of Family Studies, Melbourne. Retrieved from https://aifs.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication-documents/2007_aftn_couples.pdf

Sassler, S., & Lichter, D. T. (2020). Cohabitation and marriage: Complexity and diversity in union-formation patterns. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82, 35–61.

Sassler, S., & Schoen, R. (1999). The effect of attitudes and economic activity on marriage. National Council on Family Relations, 61(1), 147–159.

Smock, P. J., Manning, W. D., & Gupta, S. (1999). The effect of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. American Sociological Review, 64(6), 794–812.

Soons, J. P. M., & Kalmijn, M. (2009). Is marriage more than cohabitation? Well-being differences in 30 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(5), 1141–1157.

Stutzer, A., & Frey, B. S. (2004). Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? The Journal of Socio-Economics, 35, 326–347.

Sweeney, M. M. (2002). Two decades of family change: The shifting economic foundations of marriage. American Sociological Review, 67, 132–147.

Treas, J., & de Ruijter, E. (2008). Earnings and expenditures on household services in married and cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(3), 796–805.

Waite, L., & Gallagher, M. (2000). The case for marriage. Why married people are happier, healthier and better off financially. Broadway.

Wiik, K. A., Keizer, R., & Lappegård, T. (2012). Relationship quality in marital and cohabiting unions across Europe. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 389–398.

Wilkins, R., Botha, F., Vera-Toscano, E., & Wooden, M. (2020). The household, income, and labour dynamics in Australia survey: Selected findings from waves 1–18. Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic & Social Research, University of Melbourne.

Woolridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press.

Zhou, C. (2021, May 26). Australia Talks National Survey reveals what Australians think about marriage and children. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-05-26/australia-talks-national-survey-children-marriage/10014639

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lee, R., Baxter, J. (2022). Marriage Matters. Or Does It?. In: Baxter, J., Lam, J., Povey, J., Lee, R., Zubrick, S.R. (eds) Family Dynamics over the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 15. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-12223-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-12224-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)