Abstract

Transdisciplinary research projects offer practical learning environments and great opportunities for students and project partners to collaborate. This chapter presents two examples of practical seminars that provide open spaces for collaboration within the ENaQ Project in the Helleheide Urban Living Lab in Oldenburg, Germany. In these seminars, students worked directly with the project partners finding answers to actual research questions from within the project. Based on the reflections from all stakeholders and the takeaways from the seminars’ format, the authors introduce an iterative collaboration process. Transdisciplinary research projects can use it to develop the theory-practice interactions further and create a win-win collaboration in a long-term profit for all parties.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Sustainable Development in general and energy transition, in particular, are goals in which Higher Education Institutions (HEI) play an essential role, as seen, for example, in Radinger-Peer and Pflitsch (2017)). Other stakeholders are also important players in achieving these goals, and when it comes to regional transitions, the collaboration between HEI and other stakeholders is particularly relevant. Teaching spaces offer one possibility for such collaborations (Hoinle et al., 2021). In this sense, transdisciplinarity research is understood as scientific cooperation between not only different disciplines but also with nonacademic actors. It has the explicit aim of finding solutions to complex societal problems. Its results are transferable to both society and academia, enabling mutual learning processes to become increasingly relevant (Jahn et al., 2012; Lang et al., 2012).

Therefore, conceptualizing teaching and learning formats that integrate content and questions from transdisciplinary research projects can be an innovative teaching approach that can help promote regional sustainability. In this way, students, project partners, and lecturers can benefit from collaboration and knowledge exchange. As we will see in Section 3, practice-oriented learning or experiential learning offers opportunities for students to apply their theoretically gained knowledge and prepares them for their professional careers (Kolb, 2014; Gentry, 1990). Project partners can profit from new and innovative ideas from a mostly younger generation, bringing in external views that can stimulate the project process. Finally, lecturers also benefit from an innovative and integrated teaching experience.

The transdisciplinary research project ENaQ [Energetic Urban Neighbourhood] (in German: Energetisches Nachbarschaftsquartier Fliegerhorst Oldenburg) aims at designing a sustainable neighborhood in the city of Oldenburg, GermanyFootnote 1 and offers an ideal environment for this type of collaboration in teaching. ENaQ strives for a regional energy transition and social innovations. Participation plays a significant role as 21 project partners from industry, science, and local administration are part of the project. Furthermore, it takes place in the Helleheide Neighborhood, a hybrid urban living lab (Brandt et al., 2021). Thus, this chapter is based on the experiences from two practical seminars at two academic institutions that are partners in the project. One seminar was designed and implemented by the chair of Social Entrepreneurship at the Sustainability Faculty at the Leuphana University Lüneburg in collaboration with the Chair of Business Information Systems from the University of Oldenburg and the other by the chair of Ecological Economics also at the University of Oldenburg.

Taking into consideration that seminars are a teaching format that has existed for a long time and are well-known for its characteristic of active students’ participation, with room for discussions, exchange, and learning from peers (Bates, 2014), we want to specify that practical seminars are those in which on top of the above mentioned characteristics the theory is not only discussed, it meets the real-world praxis. One goal is that practical seminars are oriented toward the professionalization of students since they take the theory out of the classroom and into the world, as seen in Germany with, for example, teachers’ training (Dohrmann & Nordmeier, 2020; Krofta et al., 2012). Furthermore, such practical seminar formats align with the proposal of meaningful or deep approach learning. The students’ interest goes beyond a grade or credit points, and a genuine interest in the topic, for example, motivates the learning experience. In this sense, approaches such as problem solving and critical thinking fit very well in this kind of learning (Bates, 2014) and are found in the practical seminars introduced in this chapter.

Furthermore, in the examples introduced here, we use extensive teaching models. The students work in compressed time periods, so-called block seminars, instead of the regular weekly sessions (Davies, 2006). This was particularly helpful in coordinating the work with the partners and the excursion to the project site. Furthermore, practical seminars could be categorized as a form of experiential learning (Kolb, 2014; Gentry, 1990). They are also very similar to how Halberstadt et al. (2019), describe as service learning approach: bringing the classroom and the real world together. However, in our examples, instead of working with community service, the collaboration is within a transdisciplinary research project in an urban living lab.

The question remains what is then an innovative teaching format. We adopted the definition of Ferrari et al. (2009), in which innovative teaching goes hand in hand with creative learning. This best fits the seminar’s goals and align with the project: "any learning that involves understanding and new awareness, which allows the learner to go beyond notional acquisition, and focuses on thinking skills. It is based on learner empowerment and centeredness. The creative experience is seen as opposite to the reproductive experience. Innovation is the application of such a process or product in order to benefit a domain or field—in this case, teaching. Therefore, innovative teaching is the process leading to creative learning, the implementation of new methods, tools and contents which could benefit learners and their creative potential” (Ferrari et al., 2009, p. iii).

In the context of the seminars, the students benefited from learning by being directly involved in research that engages with a real transdisciplinary project. The nexus of research and teaching, although sometimes criticized, is not recent. Humbolt already called for universities to always be in research mode; others claim that it is essential for the students’ engagement and motivation, not only for the students but also for the lecturers (Healey, 2007; Healey et al., 2010; Griffiths, 2004).

In Sect. 2, we introduce the seminars’ concepts, overall context, and the contents of the different sessions. Secondly, Sect. 3 summarizes the results derived from short surveys containing qualitative and quantitative questions which project partners and students answered after the course and which the lecturers used in their reflection. Thirdly, based on the reflections from all stakeholders, we have determined eight key takeaways for future seminars which can be found in Sect. 4. In these, you find what we believe is essential advice for those planning the same or similar formats. Fourthly, in Sect. 5 we introduce a collaboration process based on the experiences and the gained learning. We propose what a long-term collaboration between a transdisciplinary research project and HEI through such formats could look like, and we finalized with a summary and limitations.

2 Conceptualizing Practical Seminars

A key aspect of the transdisciplinary ENaQ project is to offer various possibilities for stakeholders to participate. The participation process design includes four dimensions that enables different participation formats. Incorporating project content and questions into teaching formats is found within the Neighborhood Research dimension, including seminars, student research projects, bachelor’s or master’s theses, or student projects. A thorough description of the participation process design can be seen in Brandt et al. (2021).

As academic project partners, the Leuphana University LüneburgFootnote 2 and the University of Oldenburg offered practical seminars to create a space for exchange, cooperation, and learning. Both seminars were (partly) facilitated by researchers who were also working on the project. In this section goals, frameworks, and a description of the two seminars from each University are presented.

A summarizing table including some commonalities and distinctions can be found at the end of this section Fig. 3.

2.1 Practical Seminar at the Leuphana University Lüneburg

The seminar at the Leuphana University Lüneburg took place in the winter term of 2018/19, with 35 participants from seven different study programs, including, for example, Sustainability Science, Cultural Studies, or Management and Engineering. It was one of the elective seminars within the required module: Connecting Science, Responsibility and Society. As mentioned before, it was carried out by the Junior Professor for Social Entrepreneurship with her researchers in collaboration with the Chair of Business Information Systems from the University of Oldenburg.

As part of the seminar Innovations and Inmovations for Energetic Neighborhoods at the Leuphana University Lüeburg, students were actively involved in the ENaQ research project. The seminar aimed to get to know and experience the application-oriented approach of a living lab in Oldenburg. The lecturers facilitated a setting to conduct practical research in small groups, working closely with the project partners. The seminar offered the opportunity to gain insights into a flagship project in a smart city context and to enter into an active dialogue with various stakeholders and participating social actors to develop visions for sustainability in ENaQ.

The seminar was organized in the form of a block seminar divided into three sessions, plus up to two individual meetings with the project partners. The first session was half a day kick-off event in Lüneburg. In this session, we introduced the concept, framework conditions, and issues to be dealt with in the Fliegerhorst context. The seven participating project partners introduced themselves via video conference (Skype) and each presented a few slides on their role and task in the project as well as on the research question(s) or task(s) they wanted to collaborate on. Some of the topics were, for example:

-

A lighting concept for the neighborhood considering the needs of the citizens

-

A conceptual design for a common room based on scientific literature and further derivation of best practice examples

-

How can citizens in the ENaQ area be more aware of energy (electricity, heat, mobility) in the neighborhood? How can measurement data (electricity, heat, mobility) be presented clearly?

The students were then able to select one of the various questions they would want to work with. The seminar facilitators ensured that the groups were as heterogeneous as possible, particularly in relation to the study programs. The team’s size was three to four students, except for a team of two. The teams were then asked to use an Idea Canvas, as seen in Fig. 1. This canvas was designed by two of the facilitators. It was inspired by the classic business model canvas (Osterwalder et al., 2011) and based on the facilitators’ previous experiences with other seminars in which the canvas was very helpful.

The idea canvas goal is to record the first ideas for the respective question in ten fields: to define the goal, the direct and indirect target groups, to think about resources, potential partners, and communication, as well as first considerations on costs, profit, and a simple timetable with the next three steps for the team to define.

Following this first session, the ten teams independently contacted their respective project partners to clarify further details and expectations concerning the question or task. The lecturers informed the project partners in advance that a maximum of two individual meetings should be sufficient for the student research groups to start.

Seven weeks later, the second session took place as a one-day excursion to Oldenburg. The students could visit the site where the project was being developed at the former airbase site Fliegerhorst and personally meet the partners involved. In this context, the students gave a first short presentation on their ongoing results and presented questions essential to clarify for the final presentation. This task was solved very successfully and promisingly by all ten teams. Feedback was first collected in the plenary session, followed by an intensive exchange of the teams individually with the respective partner they worked with.

For this purpose, the students used a four-field feedback matrix, as it can be seen in Fig. 2, which was also designed again by two lecturers specifically for this purpose. It was inspired on a SWOT analysis matrix as seen in, for example Gomer & Hille (2015) but adapted and further extended to evaluate the intermediate status of ideas. On the one hand, it is about what previous results are and where problems may arise, how the stakeholders can overcome possible obstacles, what is promising and should be deepened, and finally, what a first prototype for the idea could look like and what next steps are.

With the feedback from this context, the teams were asked to refine their previous ideas over the next six weeks and, if necessary, to work out the first prototype. At the end of the semester, the final session took place in which all ten teams presented their results. For this session, we invited all partners in the consortium. The teams made 10–15 min presentations, followed by questions from the partners, lecturers, and fellow students. This session took place at the University, and the partners participated online via Skype. Finally, the students handed in a thorough report on their recommendations for action for the partners, which was also the assignment. The lecturers recommended including a reflection on the seminar’s learnings in their final assignment, but this was optional.

2.2 Practical Seminar at the University of Oldenburg

The practical seminar at the University of Oldenburg took place in the winter term 2020/21, and researchers of the chair of Ecological Economics were the facilitators. The students that took part in the seminar were from the Sustainability Economics and Management or Landscape Ecology study programs.

The general seminar concept aims to give students a theoretical understanding and an idea of practical concepts of citizen participation. Additionally, the student groups had to develop a participatory format for the ENaQ project on a concrete topic or question, which they had to carry out by the end of the semester. Choosing an adequate participatory format according to the intention behind the topic was entirely the students’ responsibility within the seminar time frame. Therefore, students applied the theoretical knowledge they had acquired in practice and reflected on their procedure afterward. The facilitators asked all project partners to submit possible topics that the students could address within a citizen participation format framework.

The semester started with an introductory session. The project partners presented their submitted topics to the students during the first part. After which, the students formed groups of no more than five people, according to the student’s interests. One exception has been made with one group of six students. In the second part of the first session, the students joined a guided walking tour through the project area. Several project partners presented different project-relevant topics like housing and neighborhood or application fields for hydrogen technology. During the seminar, the lecturers offered two theoretical input sessions during the first weeks. The lecturers allocated the rest of the seminar time for self-organized group work. The lecturers provided consultancy hours upon request.

In the eighth week of the semester, the three student teams presented their interim results to the other groups and to the project partners who submitted the topics. The presentations included:

-

Theoretical background information about the topic.

-

The aim of the individual participation process.

-

The definition of the target groups as well as an outreach strategy for those groups.

-

The choice of the participation format.

-

The selected method.

-

Challenges the teams were facing during the preparation time.

During the online presentations, the lecturers used the digital tool Mural to collect feedback and questions from the project partners and their peers, which was helpful for the students to get feedback about the ideas they had developed. The student groups carried out their participatory formats within the last four weeks of the lecture time. One group developed and carried out an online citizens workshop on "Living without a car: How can we promote the use of car-free mobility concepts in Oldenburg? - Working out new ways together!" The two other groups designed and conducted online surveys on "Energy visualization and energy feedback" and "Guide to living in a sustainable neighborhood."

The students presented their results to the project partners and their peers in the last session. The lecturers again prepared the digital tool Mural to collect feedback remarks and questions on each student group’s presentations. The students submitted a written assignment by the end of the semester, including a procedure description, results, reflection, and learning. This seminar occurred during COVID-19-related contact restrictions; all sessions except the first one were carried out digitally.

In Table 1, you can see the general information of each and which similarities and differences they have. In both seminars, the students had the opportunity and the time for a high level of independent and self-organized group work, experiencing project and team management and coordination as further learning.

We invite you to use the tools we introduced here in your seminars.

3 Reflection

The two seminars were evaluated by the students and the involved project partners by taking part in a short online survey that the lecturers conducted. We use some of the same questions from a general Leuphana evaluation survey which is conducted every semester. The survey contained qualitative and quantitative questions on a scale from 1 to 5. The results of this survey are used to derive learnings for academic–practice collaborations and especially for the involvement of students as academic actors in research projects. The results are additionally used to improve the concepts for future practical seminars within the ENaQ project.

3.1 Perspective of the Students

The survey outcome revealed different aspects of the students’ motivation to participate in the seminar and the strengths and weaknesses of the seminar concepts. Furthermore, the students were asked to assess their experiences of the theory–practice interplay within the course. The two main aspects that sparked the interest in the seminars and motivated the students to select them were, on the one hand, their interest in the topics of renewable energies, urban living districts, or the local context of the Fliegerhorst district and the living lab Helleheide. On the other hand, the practical setup includes collaboration with real project partners.

The students highlighted the following aspects of the seminar as positive. Firstly, the practical context, working on an actual project, cooperating with project partners, and possible implementation of the results. Secondly, the students appreciated the freedom of making independent decisions on the selection and the design of the questions or tasks to work with or the participatory formats. Thirdly, the group work was also considered a positive aspect.

In contrast to these positive aspects, they were also asked to state the deficits of the course. The main points mentioned were that they perceived the communication between the lecturers and the project partners as not sufficient due to unclear expectations. Furthermore, they addressed the lack of introduction of a wider variety of participatory formats as a theoretical input to choose from, the lack of time for the presentation of the project, the concept, and partners, and for the discussion.

Apart from these qualitative statements, the students were asked to evaluate various aspects of the seminar by indicating to which level they agree or disagree with certain statements.

The statement "In the course, theoretical content was meaningfully linked to the practical topics/practical examples." was agreed on by 23% of the students, whereas 31% were indifferent and 46% rather disagreed. This outcome is reflected as well in the mentioned weaknesses of the course. Most of the students did not consider the theoretical inputs as relevant to the practical context. In addition, the following statement, "For me personally, the course offered the opportunity to apply what I had learned in theory practically." confirms the missing linkage between theory-practice compatibility as 15% rather agreed, 54 percent were indifferent, and 31% rather disagreed.

The following statement, "I was able to bring in my own practical experience into the course." was answered by 69% rather positive, 15% indifferent, and 15% rather disagreed. The comment "During the course I was able to acquire professional skills." was answered by 53% of the students positively, 38 percent were indifferent, and 8% rather disagreed. Both results show the overall positive assessment of the course in having created an open practical space where students could bring in their own competencies and at the same time acquire other relevant skills. In one free-text field, one student appreciated the "opportunity to try out practical things and make mistakes," which underlined the idea of creating an experimental space with own responsibility for students. The statement "I consider the content and methods taught as well as the experience gained to be relevant to my (future) professional practice." was rather agreed on by 54% of the students, 31% were indifferent, while 15% rather disagreed. The majority perceived the course content as practically relevant, highlighting the beneficial setting of student-practice interactions.

Eighty-five percent agreed with the comment "I found the collaboration with practice partners to be enriching." while 15% were indifferent. This outcome points out the benefits of collaborations between students and practical partners.

It is relevant to mention that the number of students that took part in the survey is a limitation. In the case of Leuphana, out of 35 students, only 11 responded to the evaluation survey. In the survey at the University of Oldenburg there were 13 respondents.

3.2 Perspective of the Project Partners

The results from the project partners’ survey show the strengths and weaknesses of the seminar from their perspectives. Furthermore, they were asked to assess their experiences in collaborating with students and the achieved outcomes.

As a strength, the partners mentioned the value of a critical view from outside the project to get direct feedback. Additionally, they described the active exchange with students as fruitful, which led to new ideas and ultimately usable results.

There were also some aspects which they considered as having a potential for improvement. These included: more time is needed, more interdisciplinary teams, and the communication between the lecturers and the project partners should be more regular.

Apart from these qualitative statements, the project partners were asked to evaluate various aspects of the seminar by indicating to which level they agree or disagree with certain statements. The results are as follows:

All involved project partners agreed on the statement, "I found the collaboration with the students enriching." which shows the overall satisfaction with the seminar. Fifty percent of the project partners rather agreed with the statement "New ideas emerged as part of the collaboration with the students." whereby 33 percent were indifferent, and 17% rather disagreed. The assessment of the comment "The results of the student groups were constructive and valuable." shows that 83% rather agreed with it while 17 were indifferent. Also, this demonstrates that the partners somehow benefited from the outcomes.

Sixty-seven percent of the partners rather agreed with the statement "The effort of accompanying the student groups was appropriate." while the rest did not respond to this question. "The effort of accompanying the student groups was worth it." was rather agreed on by 83%, whereby 17% did not answer this question. Ultimately, all project partners agreed, "I can imagine having students working on a topic as part of a practical project and supervising it content-wise.”

The response quota was of six from eight partners that collaborated in one or both seminars.

3.3 Perspective of the Lecturers

From our perspective as co-lecturers, we believe that the cooperation with the project partners was fruitful. We were able to see the research project from different perspectives and have learned more in terms of content. Furthermore, it was possible to observe how the students became increasingly confident in communicating and working with their project partners and that they continuously expanded these skills.

Concerning the results of the student groups, the developed ideas were refreshing and positively surprising. From the partners’ perspective, there were different positions, but for us as lecturers, a significant knowledge gain and options, which ultimately benefited the overall project, resulted from the seminars.

We completely underestimated the time required for communication with the students. The limited number of face-to-face interactions and exchange sessions prompted more questions from the partners and even more so from the students. Answering these appropriately and giving feedback on their work processes took enormous time.

The communication within the research project was more accessible for the Oldenburg seminar since the partners already had experienced a first practical project seminar at Leuphana and therefore already knew the procedure and the added value, therefore they could better estimate the effort and adjust their overall questions and topics accordingly. Thus, establishing a long-term and sustainable cooperation with the project partners could bring added value for all parties involved. Therefore, in Sect. 5. we introduce a collaboration process in which different student groups can work with research questions and ideas beyond the duration of only one semester

4 Lessons Learned

Based on the reflections in the previous Sect. 3, we have defined the following eight key learnings and advice for future seminars:

-

1.

Give your students a chance:

In exchanges with other lecturers, we sometimes hear that students may not yet have enough knowledge or experience to work independently and being responsible for actual project tasks. We want to emphasize that the results of the students’ work often exceeded our expectations. The students are young adults who enjoy being taken seriously and, given the opportunity, will, in most cases, give their best. Therefore, have confidence in your student teams, and you will not be disappointed.

-

2.

More exchange with the project partners:

Additional interaction between lecturers and project partners could help with a smoother collaboration and might have led to even better results. For example, after the presentations mid-semester, it would have been a good time to point out again as a lecturer what the project partners noticed or to be able to provide concrete assistance from the lecturer’s perspective. The project partners did not complain that they had to give too much input. In this respect, this would surely be a worthwhile additional investment for the lecturers and the partners.

-

3.

Use of canvas model and feedback matrix:

Using an idea canvas at the beginning of the project has proven very effective. Thanks to the framework set up with the help of the canvas, the students quickly knew what was important when developing ideas, and the tasks were thus somewhat more comparable. Therefore, our recommendation would be to always use such a canvas as a framework that can guide the students and support the process of refining the topic further and further. The same goes for the feedback matrix. It is helpful when important aspects are summarized on one page and given a specific structure. Such canvases or matrices can always be adapted to the seminar’s goals and needs.

-

4.

Incentives to create a prototype:

Unfortunately, the students did not create hardly any noteworthy (haptic) prototypes that would have made the respective ideas even more tangible. This may have been since the students were asked to analyze and make recommendations for action, which is primarily done in writing. An incentive could be, for instance, that the project partners provide a small budget or that the best prototype is awarded a prize at the end of the seminar. This would give the students the experience of how helpful and motivating the development of a prototype can be, which is particularly essential in business model development. A short input in one of the sessions or an extra session for this purpose should also be considered.

-

5.

Use comparable questions and evaluation criteria for the examinations:

We noted that the comparability of the different project groups and results and evaluating their performance was difficult due to the various questions. Here, our recommendation is to consider with the project partners at an early stage and determine how the tasks can be designed as similarly as possible in terms of scope and workload. This also affects the comparability concerning the examination performances. The students want to understand why their grades may differ. For this purpose, transparent evaluation criteria should ideally be defined jointly by lecturers and project partners in advance.

-

6.

Do not underestimate the time required for organization and support:

Potential for improvement and optimization was seen primarily in time management. Students recommended having an even more detailed presentation of the neighborhood concept and the partners to understand the research project’s goals better. In addition, the need for more time for discussion in the individual meetings was made clear. Therefore, our recommendation is to plan more time for communication with students and project partners from the start and to include appropriate time slots in the seminar format.

-

7.

Courage to go digital:

The two seminars took place at different times: The Oldenburg seminar was in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic when we were accustomed to using digital tools. The Lüneburg seminar took place when we could hardly imagine lockdowns and the mobility restriction to the extent we experienced in 2020/21 when the Oldenburg Seminar took place. Nevertheless, because of the different locations with a distance of 200 kilometers, around 50 percent of the Leuphana Seminar took place with the help of digital tools and phone calls. Therefore, long distances should not be an obstacle to holding seminars with project partners. On the contrary, given digital developments, these will be even better and easier to carry out in the future!

-

8.

Strive for long-term cooperation!

The effort for a practical seminar is particularly worthwhile if the cooperation with the partners can be repeated or continued several times. As we will describe in Sect. 5 the most significant added value of collaborating with research projects lies in the possibility of working with questions and ideas that different project teams over several semesters can further develop. Therefore, consider whether you can offer a seminar format over several semesters if possible.

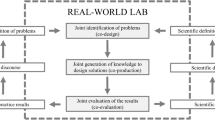

5 Collaboration Process

After two practical seminars in two different universities within the living lab project ENaQ and after reflecting on the learnings from all three different perspectives, comparing both seminars, and looking into synergies that could be beneficial, we want to introduce a collaboration process in which universities and transdisciplinary research projects can further work together while profiting even further from the collaboration.

As we learned in the previous section, partners benefit from the input and ideas of the students. We also learned that a straightforward research question or task helps create a sound output. Considering that the seminar time is limited, it should always be kept in mind that finding answers to a very extensive or lengthy research question or task is not possible. Therefore, we propose an iterative collaboration process in which the research question is divided into smaller aspects that different groups can deal with and build upon during several semesters in an iterative process together with the project partners. After each semester, the students give a detailed report to the partner who uses the results, applies them, or develops them further. The following semester, or if required, two semesters later, a new group of students receives the first report from the previous group plus the development done by the partner and a follow-up research question or task they will work with. This process can continue for several semesters, as seen in Fig. 3. Each semester, a new student group works on a research question or task, building upon the students’ work in the previous semester and the implementation or test by the partner.

Such a process has the following advantages:

-

It is possible to work with broader research questions, which can be broken down into more minor aspects for each semester.

-

There is a higher chance to use the work of the students given the iterative process, building upon the previous ideas.

-

The students and the partners can see and learn from the evolution of the ideas and previous results.

Such a process requires a particular effort on the side of the partners: a longer commitment to work with students, the processing or evaluation of the results, and to make sure to have clear communication in the form of a report for the new group. On the side of the students, reporting and communication become even more critical since the following semester, a new group of students will be working further with the materials, information, and ideas.

Seeing how the ideas and results presented in the two ENaQ seminars in both Leuphana University Lüneburg and the University of Oldenburg, we are confident that such an iterative collaboration process would have been profitable for all parties, the learning experience would be richer, and the input for the project larger.

One concrete example within the ENaQ project in which we could visualize such a collaboration process is the energy signal lamp. This lamp could help or motivate the residents to improve the use of, for example, local energy (Klement et al., 2022). An initial student group can work with a survey asking users about the interest, needs, and likes of a visualization tool that informs households about their energy consumption. A partner who develops this technology can better understand which elements are considered relevant from a user perspective using this information. Having a first prototype developed next semester, a new group of students can design workshops with users to test the prototype and develop the ideas further. In an iterative process, a partner can further develop the outcome of the prototype, and the third group of students can check the usability of the tool. After three semesters, a user-oriented tool, developed through citizens’ participation and allowing students to be an active part of the research, has been developed and can be used in the living lab. The process can end here, or a fourth group can take the task of evaluating the use of the visualization tool or working on a business model.

As mentioned above, this collaboration process enlarges the options of research questions and tasks and therefore widens the possibilities. The iteration allows the lecturers to improve the seminar and gives the students the chance to work on an actual research project theoretically and experience it in practice. We believe such a process can be helpful not only in the context of living labs but in transdisciplinary research projects in general and has the potential to make the relationship between the partners, universities, and companies stronger, given a more extended time commitment of working together.

6 Conclusion

As we have seen in this chapter and in the description of the practical seminars, particularly with the feedback from the different stakeholders, it is clear that theory–practice interactions between student groups and partners in real transdisciplinary research projects offer great potential for experiential learning and exchanging new, innovative ideas. From our experiences, we formulated key learnings for those interested in trying out the same or similar formats. The eight key learnings in Sect. 4 provide valuable advice on successfully carrying out collaboration. Furthermore, Sect. 5 introduces an iterative collaboration process that would help involve more broad topics or long-term aspects to be developed during several semesters. With this process, feedback and new outcomes can be applied and integrated in between the consecutive semesters. Thus, the time-wise limitation to one semester can be overcome. Thus far, this collaboration process is an idea we would like to implement in the near future. Further development could also include cooperation between student seminars from different involved universities within a project. In this way, student teams can be, for example, more interdisciplinary. Apart from developing the content and research questions, the structure of the seminar can be adjusted by the lecturers according to the project partners and students’ needs.

Notes

- 1.

More background information and insights into the project can be found in (Brandt et al., 2021).

- 2.

The Leuphana University Lüneburg was partner until 2018, changing from 2019 to the University of Vechta.

References

Bates, A. (2014). Teaching in a digital age by Anthony William (Tony) bates. Tony Bates Associates Ltd Vancouver BC.

Brandt, T., Schmeling, L., Alcorta de Bronstein, A., Schaefer, E., & Unger, A. (2021). Smart energy sharing in a German living lab. from participation to business model. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics Governance.

Davies, W. M. (2006). Intensive teaching formats: A review. Issues in Educational Research, 16(1), 1–20.

Dohrmann, R., & Nordmeier, V. (2020). Die verknu¨pfung von theorie und praxis im lehr-lernlabor-blockseminar als unterstu¨tzung der professionalisierung angehender lehrpersonen. In Lehr-lern-labore (pp. 191–207). Springer.

Ferrari, A., Cachia, R., & Punie, Y. (2009). Innovation and creativity in education and training in the EU member states: Fostering creative learning and supporting innovative teaching. JRC Technical Note, 52374, 64.

Gentry, J. W. (1990). What is experiential learning. Guide to business gaming and experiential learning, 9, 20.

Gomer, J., & Hille, J. (2015). An essential guide to SWOT analysis. The Millennium Cities Initiative, Earth Institute Columbia University. http://mci.ei.columbia.edu/files/2012/12/An-Essential-Guide-to-SWOT-Analysis.pdf

Griffiths, R. (2004). Knowledge production and the research–teaching nexus: The case of the built environment disciplines. Studies in Higher education, 29(6), 709–726.

Halberstadt, J., Schank, C., Euler, M., & Harms, R. (2019). Learning sustainability entrepreneurship by doing: Providing a lecturer-oriented service learning framework. Sustainability, 11(5), 1217.

Healey, M. (2007). Linking discipline-based research and teaching to benefit student learning. In Meeting of institutional contacts and project directors (Vol. 25).

Healey, M., O’Connor, K. M., & Broadfoot, P. (2010). Reflections on engaging students in the process and product of strategy development for learning, teaching, and assessment: an institutional case study. International Journal for Academic Development, 15(1), 19–32.

Hoinle, B., Roose, I., & Shekhar, H. (2021). Creating transdisciplinary teaching spaces. Cooperation of universities and non-university partners to design higher education for regional sustainable transition. Sustainability, 13(7), 3680.

Jahn, T., Bergmann, M., & Keil, F. (2012). Transdisciplinarity: Between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecological Economics, 79, 1–10.

Klement, P., Brandt, T., Schmeling, L., Alcorta de Bronstein, A., Wehkamp, S., Penaherrera Vaca, F. A., et al. (2022). Local energy markets in action: Smart integration of national markets, distributed energy resources and incentivisation to promote citizen participation. Energies, 15(8), 2749.

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT press.

Krofta, H., Fandrich, J., & Nordmeier, V. (2012). Professionalisierung im Schülerlabor: Praxisseminare in der Lehrerbildung.

Lang, D. J., Wiek, A., Bergmann, M., Stauffacher, M., Martens, P., Moll, P., et al. (2012). Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7(1), 25–43.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Oliveira, M. A.-Y., & Ferreira, J. J. P. (2011). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers and challengers. African journal of business management, 5(7), 22–30.

Radinger-Peer, V., & Pflitsch, G. (2017). The role of higher education institutions in regional transition paths towards sustainability. Review of Regional Research, 37(2), 161–187.

Acknowledgments and Funding

The authors thank all the other ENaQ project partners for support, inspiration, and fruitful discussions before, during, and after the seminar. They also want to thank the students in both universities for their active participation and contribution, Prof. Jantje Halberstadt and Prof. Jorge Marx Gómez, co-lecturers at the Leuphana Seminar, and Dr. Theresa Anna Michel and Dr. Torsten Grothmann, co-lecturers in the seminar at the University of Oldenburg. This research was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWi) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) of Germany in the project ENaQ (project number 03SBE111).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Unger, A., Alcorta de Bronstein, A., Timoschenko, T. (2023). Transdisciplinary Learning Experiences in an Urban Living Lab: Practical Seminars as Collaboration Format. In: Halberstadt, J., Alcorta de Bronstein, A., Greyling, J., Bissett, S. (eds) Transforming Entrepreneurship Education. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11578-3_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11578-3_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-11577-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-11578-3

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)