Abstract

This chapter considers the role of positive emotions in religion/spirituality. We begin by reviewing key conceptual frameworks of positive emotions (e.g., Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions) while focusing on self-transcendent positive emotions such as awe, gratitude, love, and compassion. We then review scientific research on the bidirectional relationship between religion/spirituality and positive emotions. First, we examine various pathways through which religion/spirituality promotes the experience of positive emotions. For example, research has shown that religion/spirituality is related to specific valued emotions and particular emotion-regulation strategies. In addition, religious/spiritual (R/S) practices provide the opportunity to experience positive emotions, partly through emotional embodiment. Second, we propose four effects of positive emotions related to religion/spirituality. Positive emotions support R/S beliefs, and when they are felt during R/S practices, they function as promoters of well-being, prosocial intentions and behaviors, and continued R/S practices (the Upward Spiral Theory of Sustained Religious Practice). We close by offering some applications of these findings for mental health practitioners, religious leaders, and religiously/spiritually oriented people.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

In The Brothers Karamazov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky alludes to a kind of spiritual ecstasy achieved through religious devotion: “My friends, pray to God for gladness. Be glad as children, as the birds of heaven” (Dostoyevsky et al., 1933, p. 335). Indeed, in literature, philosophy, as well as everyday life, religion/spirituality is closely associated with positive emotions.

However, despite the important role positive affect plays in religion/spirituality, the relationship between positive emotions and religion/spirituality has received little attention from empirical researchers. In this chapter, we first conduct a systematic review of existing research on the bidirectional relationship between positive emotions and religion/spirituality. We show that religious/spiritual (R/S) practices generate the experience of positive emotions via multiple means and reflect the expression of positive emotional experiences. We also discuss the practical implications of this relationship, focusing on four major effects of positive emotions in religion/spirituality: (a) supporting beliefs, (b) improving well-being, (c) promoting prosocial behaviors, and (d) maintaining R/S practices (the Upward Spiral Theory of Sustained Religious Practice; Van Cappellen et al., 2021).

Positive Emotions

Positive emotions are brief mental, physiological, and behavioral responses to changes in how someone interprets (appraises) their current circumstances (Fredrickson, 2013). Positive emotions tend to share three distinguishing characteristics: (a) they serve an adaptive (health-promoting) function, (b) they engage in an approach (appetitive) motivation, and (c) they involve pleasant feelings (Smith et al., 2014). There are a wide variety of positive emotions, including joy, gratitude, serenity (contentment), hope, interest, pride, amusement, inspiration, awe, admiration, or love (Fredrickson, 2013).

According to the Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions (Fredrickson, 2013), feeling momentary positive emotions broadens one’s mindset (momentary repertoire of thoughts and actions) and enables one to think and act more creatively. As these brief moments of positive emotions accumulate and compound over time, positive emotions build enduring psychological (e.g., resilience, purpose in life), biological (e.g., reduced illness symptoms, cardiac vagal tone), and social (e.g., good quality relationships, received social support) resources for survival. In addition, positive emotions may have an “undoing effect” (Fredrickson et al., 2000, p. 237) on negative emotions. The effects of negative emotions often linger after the negative circumstances that caused the negative emotions are no longer present, but the experience of positive emotions speeds up recovery from these lingering effects (Fredrickson et al., 2000).

Yet positive emotions do not all have the same qualities and effects (Fredrickson, 2013; Sauter, 2010). One subset of positive emotions is called self-transcendent positive emotions, because they have a self-transcendent quality to them. These emotions include awe, gratitude, love, compassion, and admiration. Self-transcendent emotions are a subset of self-transcendent experiences, and as such, they are “marked by decreased self-salience and increased feelings of connectedness” (Yaden et al., 2017, p. 143). Indeed, Haidt (2003) has described them as emotions that rise above self-interest and often are associated with the welfare of others. As reviewed below, even more so than other positive emotions like pride or amusement, self-transcendent positive emotions seem universally central to R/S experience.

Religion/Spirituality and the Promotion of Positive Emotions

Although for many people it may not come as a surprise that religion/spirituality can generate the experience of positive emotions, empirical research on the topic is fairly nascent. Overall, extant studies suggest that R/S beliefs and practices are related to positive emotions (Myers, 2018), especially to self-transcendent emotions such as gratitude (Emmons & Kneetzel, 2005; Kim-Prieto & Diener, 2009). Daily experiences of spirituality are positively related to happiness (Ellison & Fan, 2008), and deep religious and mystical experiences are often accompanied by intense positive emotions such as joy, peace, and reverence (Yaden et al., 2017). For example, in a cross-cultural study among Black, White, Latinx, and Korean members of Pentecostal and Presbyterian churches, linguistic analyses showed that narrative accounts of closeness to God and spiritual transformations were filled with references to positive emotions, especially gratitude (Abernethy et al., 2016).

How exactly does religion/spirituality promote positive emotions, especially self-transcendent ones? Below we emphasize two paths. One path targets R/S beliefs as a source of valuing self-transcendent emotion and of guiding adaptive emotion regulation. Another path targets R/S practices that provide opportunities to experience positive emotions; here we present new work from our team on the role of embodiment in religious practice.

Emotion Regulation and Values

R/S beliefs shape the kind of emotions that the people who hold those beliefs value. In general, R/S people value positive emotions more than people who are less religious do (Vishkin et al., 2019). Specifically, Christians value high-arousal positive affect, whereas Buddhists value low-arousal positive affect (Tsai et al., 2007). Members of most major religious groups (Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus—but not Jews) report valuing the positive emotions of love, gratitude, and happiness to a greater extent than the positive emotion of pride (Kim-Prieto & Diener, 2009). In addition, according to Belief Maintenance theory (Vishkin et al., 2020), people who embrace R/S beliefs tend to seek out certain affective experiences that are congruent with their beliefs. Therefore, they are particularly motivated to pursue self-transcendent positive emotions that strengthen their beliefs. For instance, in two large-scale, cross-cultural studies, Catholics, Jews, and Muslims rated how often they wanted to experience various emotions (e.g., awe, gratitude, and pride) and how often they usually experienced these emotions. Results showed that regardless of religious affiliations, religious people were more likely to value self-transcendent emotions (e.g., awe) than self-conscious emotions (e.g., pride; Vishkin et al., 2019).

In addition, religion/spirituality affects emotion-regulation strategies. Emotion regulation refers to the process in which people monitor and manage what emotions they have, when they have those emotions, and how they interpret, experience, and express them (Gross & Thompson, 2007). Research in a sample of American Catholics, Israeli Jews, and Muslim Turks has found evidence of relationships between religion/spirituality and two adaptive emotion-regulation strategies: situational acceptance and cognitive reappraisal (Vishkin et al., 2019). First, people who are R/S tend to think of themselves as existing within a larger system that is organized by a higher order. They believe that instead of fighting against this order, they should learn to live harmoniously with it. Hence, people with higher (vs. lower) religion/spirituality are apt to use situational acceptance as an emotion regulation strategy, allowing them to come to terms with a given situation and gain secondary control by adjusting their mindsets. Second, people who are R/S also tend to perceive their experiences (both personally significant events and seemingly mundane daily occurrences) as part of a larger meaning system. This tendency to reinterpret emotional events coincides with a specific emotion regulation strategy called cognitive reappraisal, which involves reframing an emotional event by changing its perceived meaning (Gross & John, 2003). Again, people with higher (vs. lower) R/S were apt to engage more frequently in cognitive reappraisal (Vishkin et al., 2019). This adaptive strategy allows R/S people to think of their negative experiences differently and to look actively for the silver lining around the cloud, which often leads to positive emotional outcomes (Gross & John, 2003).

Given that most of the work referenced in this section is recent, there is ample room for future research. In particular, researchers can explore the extent to which specific R/S practices represent practical exercises for certain emotion-regulation skills. For example, collective rituals can offer opportunities for large fluctuations in emotions (ranging from negative to positive and low arousal to high arousal) and for habitual patterns of meaning making out of emotional events. Religion/spirituality may also impact other “moments” in the emotion regulation process (Gross & John, 2003), such as selecting different emotional situations or regulating the expression of an emotion. Commendably, considerable research on this topic has been conducted with people from different religious traditions and different countries. Previous research revealed that although the examined associations did not vary widely between religious traditions, they did show some variations depending on the cultural/national context (e.g., U.S. Hindus compared to Indian Hindus), and these variations, of course, should be studied further.

Embodied Religious/Spiritual Practices

R/S practices such as meditation, prayer, and collective worship provide opportunities to experience positive emotions. Many studies, including longitudinal studies of novice meditation practitioners, indicate that meditation increases positive emotions in the moment and in daily life (Fredrickson et al., 2017; Fredrickson et al., 2008). Similarly, the practices of prayer (Lambert et al., 2009) and church attendance (Krause, 2009) increase feelings of gratitude over time (see Long & VanderWeele, Chap. 25, this volume). Moreover, the physical space in which these R/S practices take place also influences emotional experiences during them. Naturally, many places of worship are designed to elicit awe through their monumental architectures (Joye & Verpooten, 2013).

Although there are many ways in which R/S practices can affect people’s emotions, Van Cappellen’s Belief, Affect, and Behavior Lab at Duke University has recently explored the role of an understudied aspect of religion/spirituality practices—the fact that these practices involve embodied (physical) motions, gestures, and postures. Indeed, the body plays a central role in prayer, collective worship, meditation, and yoga. Postures both express and construct people’s emotional experiences. This reciprocal relationship between body and affect is supported by decades of research in affective science (Barrett & Lindquist, 2008) and grounded cognition (Winkielman et al., 2015). For example, expansive and upright postures are associated with positive feelings, whereas constrictive and slumped postures are related to negative emotions (LaFrance & Mayo, 1978).

Van Cappellen and Edwards (2021a) have reviewed such literature and discussed the implications of prayer and worship postures (which are ubiquitous in R/S practice) for people’s R/S experiences. On the one hand, these postures visibly express emotions. On the other hand, adopting certain prayer and worship postures may support the experience of particular emotions. Van Cappellen and Edwards’s (2021a) theoretical review supported both ideas. They examined two common types of postures that varied along two postural dimensions: postural orientation (upward vs. downward) and use of space (expansive vs. constrictive). Upward and expansive poses involve looking up and raising hands, whereas downward and constrictive poses involve looking down, kneeling down, clasping hands, bowing one’s head, or bowing from the waist.

In one study, U.S. Christian community participants used a small mannequin to show how they would use their full body to express various prayer orientations (prayer, worship, praise, thanksgiving, repentance, confession, and anger toward God) and emotions that varied on the affective dimensions of valence and dominance. Postures were analyzed to derive measurements of the body’s vertical, horizontal, and total space, and a coding system was developed to code for components of the body, such as head and arm positions. Results showed that postures representing prayer were systematically oriented more downwardly and constrictively than postures representing worship. Furthermore, postures representing praise and thanksgiving were more expansive and oriented upward, similar to postures representing positive emotions and dominance. By comparison, postures representing confession and repentance were more constrictive and oriented downward, similar to postures representing negative emotions and submission (Van Cappellen & Edwards, 2021b).

In another study, U.S. Christian community participants reported about the kind of body postures they adopted while attending a Sunday worship service, as well as their overall affective experiences during that same service. Participants who adopted more frequent upward and expansive postures during the church service also reported feeling more positive and high-arousal affect during the same service (more data were collected beyond emotions and can be found in Van Cappellen et al., 2021). Moreover, other studies have found that directly manipulating physical postures modifies affective experiences. Across two experiments, adults who listened to a piece of emotionally ambiguous music while raising their hands and looking upward (upward and expansive posture) experienced more positive emotions than those who listened to the same or similar piece of music while clasping their hands in prayer and looking downward (downward and constrictive posture; Van Cappellen et al., 2020).

In sum, although each of these summarized effects was small, these studies suggest the embodied nature of R/S practices provides another pathway by which religion/spirituality connects with positive emotions—by expressing and generating positive emotions. In addition, because postures are visible displays of people’s emotions, they create opportunities to recognize the emotions others are feeling and then potentially join in, thereby spreading and amplifying the experience. Further research on R/S practices, including their embodiment and how they influence emotion intensity, frequency, fluctuation, or contagion, is needed.

Positive Emotions and the Promotion of Religion/Spirituality

As reviewed above, positive emotions (experienced in any context) have the capacity to broaden the scope of attention, build enduring personal resources, and undo the effects of negative emotions (Fredrickson, 2013). In this section, we summarize research on the effects of positive emotions in relation to R/S and on the effects of positive emotions that are felt in the context of R/S practices. The first effect we describe is how positive emotions support people’s R/S beliefs. The other three effects we describe are the benefits that positive emotions experienced during R/S practices can have on health and well-being, prosocial intentions and behaviors, and continued engagement in these practices.

Positive Emotions Support R/S Beliefs

First, research shows that self-transcendent positive emotions promote R/S beliefs (e.g., “There is a higher plane of consciousness or spirituality that binds all people”). In a series of experiments, participants randomly assigned to experience awe (a self-transcendent emotion) reported greater spirituality than participants assigned to experience either amusement (a non-self-transcendent positive emotion) or no particular emotion (control condition; Saroglou et al., 2008). In two other experiments, inducing self-transcendent positive emotions of elevation (elicited by witnessing other people exemplifying moral beauty) and admiration (elicited by witnessing others’ extraordinary talents and skills) led to increased spirituality, relative to amusement and control conditions. In addition, perceived meaning in life and positive worldviews (e.g., a basic belief in the benevolence of others) explained (mediated) the relationship between self-transcendent positive emotions and spirituality. This relationship was moderated by preexisting levels of religion/spirituality. Somewhat counterintuitively, elevation (as opposed to amusement) led participants who were initially less R/S to show a higher increase in spirituality than participants who were initially more religious (Van Cappellen et al., 2013). In sum, these studies suggest that self-transcendent positive emotions such as awe, elevation, and admiration may make people more open to spiritual and transcendental experiences.

Positive Emotions Felt During R/S Practices Enhance Health/Well-Being

A second effect of positive emotions is related to their impact on health and well-being, broadly defined. The observed relationship between religion/spirituality and subjective well-being (Koenig et al., 2012) has led psychologists to investigate specifically how religion/spirituality may affect well-being. Positive emotions, which have been shown to support well-being (Fredrickson, 2013), offer one possible pathway. Correlational studies have found that dispositional gratitude uniquely predicted subjective and psychological well-being amongst Iranian Muslims and Polish Christians (Aghababaei & Tabik, 2012). Similar patterns were found in a series of studies conducted in Thailand; engaging in Buddhist practices and adhering to Buddhist values were related to higher happiness and lower negative affect, which predicted better health outcomes (Winzer & Gray, 2019). Three other studies found that religion/spirituality promoted teleological explanations of an event, which in turn increased positive emotions and thereby enhanced well-being (Ramsay et al., 2019). Finally, in another large study, Catholic participants completed questionnaires after attending their Sunday service, assessing their church experiences and subjective well-being. Results showed that religion/spirituality was related to greater well-being because of increased positive emotions felt during church, especially self-transcendent emotions. The effects of positive emotions emerged above and beyond the measured social and cognitive benefits of attending church (Van Cappellen et al., 2014). Taken together, these results lend support to the theory that positive emotions are at least partly responsible for the relationship between religion/spirituality and health/well-being. However, additional evidence from longitudinal and/or experimental studies is needed to provide more convincing support for this theory (see Chap. 8, this volume).

Positive Emotions Felt During R/S Practices Enhance Prosociality

A third effect of positive emotions—particularly self-transcendent emotions—felt in the context of R/S practices may be to promote prosociality. Because self-transcendent positive emotions promote prosocial attitudes and behaviors (Stellar et al., 2017), one study tested whether self-transcendent positive emotions felt while engaging in R/S practices might be at least partly responsible for the well-established association between religion/spirituality and prosocial behaviors. In the aforementioned sample of Catholic participants who completed questionnaires after attending their Sunday church service, the relationship between their experience while at church and their prosocial behavior intentions was assessed. Participants were asked to imagine they had just won €100,000 (around $117,000 US) at the lottery; then they were asked to describe what they would do with the money. Coders categorized these expenses as directed toward oneself or toward others (family, friends, or charities). Results indicated that higher levels of religion/spirituality were associated with greater reported willingness to share the money spontaneously with others. The self-transcendent emotion of love partially explained (mediated) the positive relationship between religion/spirituality and prosociality (sharing), whereas pride (a self-conscious emotion) was inversely associated both with religion/spirituality and with sharing (Van Cappellen et al., 2016).

In sum, preliminary evidence suggests that self-transcendent positive emotions felt while engaging in R/S practices may enhance people’s prosocial attitudes, intentions, and behaviors. However, the correlational nature of this single study in a Catholic sample limits its generalizability. Future research should test this possibility in diverse samples and directly manipulate positive emotions felt during worship, in order to explore its impact on prosociality.

Maintaining Practice: The Upward Spiral Theory of Sustained R/S Practice

The final effect of positive emotions that we will highlight stems from their role in motivating behavior maintenance (Fredrickson, 2013). Specifically, positive emotions that are experienced during R/S practices may motivate, energize, and further sustain these practices over time. R/S practices (such as worshipping, praying, or meditating) are costly in time, energy, and resources. Although it is notoriously hard to maintain costly behaviors (e.g., exercising), R/S practices surprisingly are highly prevalent and often maintained over time, despite people’s changing circumstances (e.g., moving, good or bad life events). One useful theory for explaining the social motivation for participating in collective R/S practices is the costly signaling theory (Atran & Henrich, 2010), which posits that continued engagement in costly R/S practices signals to others that one is truthfully committed to the groups’ beliefs and values. However, this hypothesis does not adequately explain the maintenance of private R/S practices (e.g., prayer), for which social signaling does not apply. We focus on the affective motivation to participate in private and collective R/S practices and suggest that when positive emotions are experienced while worshipping, praying, or meditating, they act as a motivational factor for fueling the continuation and likely recurrence of that practice.

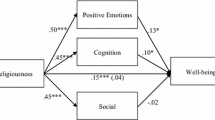

The Upward Spiral Theory of Sustained R/S Practice (Van Cappellen et al., 2021) is an empirically based explanation of the mechanisms through which positive emotions that are experienced during R/S practices build long-term maintenance of those practices. Of course, pleasant activities are repeated simply because they are pleasant. However, other mechanisms explain the relationship between feeling positive emotions during an activity and repeating that activity, as represented in the light-grey inner loops of the figure. First, positive emotions create nonconscious motives for engaging in these practices: cues related to the practice start looming larger in the environment and spontaneously pop into attention, increasing their salience in everyday life. Furthermore, positive emotions elicited by R/S practices are imbued with sacredness and connected to a broader (religious) meaning system. These sacred emotions might be more potent in driving engagement (relative to their “secular” versions) because what is considered sacred becomes salient, more powerful, and significant in people’s lives, and it further drives their engagement in activities thought to promote this sacredness (Espinola & Badrinarayanan, 2010). Over time, positive emotions felt in everyday life can also be connected back to religion/spirituality in a process of sanctification, acquiring transcendent quality and significance (Pargament & Mahoney, 2005). Together, these processes energize people’s motives for and engagement in R/S practices, providing repeated opportunities for concurrent positive emotional experiences.

Moreover, as represented in the black outer loops in the figure, positive emotions that are experienced during R/S practices and accumulated over time will gradually build enduring psychological, biological, and social resources (cf. the aforementioned Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions, Fredrickson, 2013), which will further enable the experience of positive emotions in the future. For example, sacred positive emotions experienced during collective worship will over time build social resources such as feelings of belonging within the group, which in turn will facilitate even greater enjoyment while worshipping with this group in the future. Other built resources include savoring (the ability to attend to, appreciate, and enhance positive emotions; Bryant & Veroff, 2007) or psychological well-being. In a R/S context, further spiritual resources, such as developing positive attitudes toward God (e.g., trust in God, love of God, gratitude toward God), finding spiritual strength (Van Tongeren et al., 2019), meaning (Park et al., 2017), and support (Krause, 2016), may also be gained. This process of building resources that amplify the positive emotional response to repeated practices is responsible for the namesake of the theory, and it creates upward spirals between positive emotions and R/S practices.

In Van Cappellen et al. (2021), we review the available empirical evidence supporting several paths from the model represented in Fig. 20.1. Here we only highlight areas that need further empirical studies. In particular, the behavior of meditation has received more empirical scrutiny in the context of this theory than the practices of individual and collective worship and prayer. For example, only one correlational study has demonstrated that more frequent expressions of praise and gratitude to God are associated with more frequent worship participation (Schneller & Swenson, 2013). Additional correlational and experimental studies are needed to test the hypotheses that variations in positive emotions experienced during individual and collective R/S practices (a) create nonconscious motives (e.g., positive spontaneous thoughts, salience) and (b) predict long-term maintenance of the practice. In addition, the specific flavors of positive emotions and their types of sanctification warrant further research.

Conclusion: Practical Implications and Applications

Positive emotions—especially self-transcendent positive emotions such as awe, gratitude, and love—are valued and experienced frequently by people who identify as R/S and practice religion/spirituality. As reviewed above, these positive emotions are consequential. They not only feel good, but they also have individual and collective benefits. Each effect described above provides another compelling reason for cultivating positive emotions within and outside of R/S practices. We describe the implications and applications of these findings for three groups of people.

Although not all mental health practitioners may feel comfortable engaging with their client’s R/S beliefs, they may still want to consider engaging with their clients’ R/S practices. These practices, especially if they are habitual, may provide vehicles for the experience of positive emotions that can, over time, enhance clients’ mental health and resilience. In addition, mental health practitioners may want to help clients identify other activities that for them can generate experiences of self-transcendent positive emotions (e.g., nature walks, counting blessings), which in turn may function to build clients’ meaning and religion/spirituality. Finally, mental health practitioners can teach their clients useful skills for evoking, maintaining, or increasing positive emotions. We suggest that beyond helping clients build skills for coping with negative emotions, practitioners should spend time to helping clients choose activities (and appraise such activities) in ways that support the experience of meaningful positive emotions.

Religious leaders are well-positioned to evoke positive emotions during R/S activities. For example, they can carefully consider the content of the sermon or the prayers they lead, in order to promote the experience of self-transcendent positive emotions (e.g., thanksgiving and love). Music and the physical space in which R/S practices take place are also elements that can be conducive to positive emotions. In addition, the religious leader’s own emotions can influence the mood of the entire group (Sy et al., 2005), providing another way to elicit positive emotions. Moreover, other aspects of R/S practices can be considered in order to amplify positive emotions. Collective practices allow for the experience of one person’s positive emotions to spread to others (Neumann & Strack, 2000) and get amplified by the group (cf. collective effervescence, Durkheim, 1912; Páez et al., 2015). We note that this process is facilitated by in-person collective activities because it allows for mimicry and biobehavioral synchrony. We also re-emphasize the role that embodied processes play in the visible expression and communication of positive emotions, as well as in the generation of positive emotions. In sum, we suggest that religious leaders consider strategically infusing positive emotions into their collective and embodied R/S practices, especially in contexts in which emotions can be shared and amplified.

Finally, religiously/spiritually oriented people can make efforts to seek out, notice, and savor the experiences of positive emotions that arise from their R/S practices. According to the research reviewed above, we already know that R/S people highly value the experience of self-transcendent positive emotions. Drawing on this value, R/S people can develop habits of engaging in R/S practices (and other activities) that promote the experience of positive emotions. Emotion regulatory skills can facilitate this process, such as demonstrating flexibility in choosing the right activity (e.g., leaving a group that becomes toxic) and developing the ability to attend to, appreciate, and enhance one’s own habitual positive activities, as well as the positive experiences in one’s life (cf. definition of savoring; Bryant & Veroff, 2007).

In closing, we highlight the need for more research on the bidirectional relationship between religion/spirituality and positive emotions. On the one hand, future research can focus on expanding our understanding of the ways through which religion/spirituality, and, in particular, R/S practices foster the experience of positive emotions as well as the implications of experiencing such emotions specifically during religious/spiritual practices. On the other hand, we need much more research on how positive emotions are expressed in and further support R/S beliefs and practices. Overall, while the affective correlates of meditation and collective religious practice have received some attention, we do not yet know as much about the practice of prayer. Finally, these research efforts should continue the recent trend of recruiting culturally and religiously diverse samples of participants and moving beyond convenience samples of mostly Western Christians. We argue that such research is important because it may shed light on processes that ultimately benefit individual and collective good.

References

Abernethy, A. D., Kurian, K. R., Uh, M., Rice, B., Rold, L., vanOyen-Witvliet, C., & Brown, S. (2016). Varieties of spiritual experience: A study of closeness to God, struggle, transformation, and confession-forgiveness in communal worship. Journal of Psychology & Christianity, 35(1), 9–21.

Aghababaei, N., & Tabik, M. T. (2012). Gratitude and mental health: Differences between religious and general gratitude in a Muslim context. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16(8), 761–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2012.718754

Atran, S., & Henrich, J. (2010). The evolution of religion: How cognitive by-products, adaptive learning heuristics, ritual displays, and group competition generate deep commitments to prosocial religions. Biological Theory, 5(1), 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1162/BIOT_a_00018

Barrett, L. F., & Lindquist, K. (2008). The embodiment of emotion. In G. Semin & E. Smith (Eds.), Embodied grounding: Social, cognitive, affective, and neuroscience approaches (pp. 237–262). Cambridge University Press.

Bryant, F. B., & Veroff, J. (2007). Savoring: A new model of positive experience. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dostoyevsky, F., Robinson, B., & Garnett, C. (1933). The brothers Karamazov. Halcyon house.

Durkheim, E. (1912). Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse [The elementary forms of religious life]. Alcan.

Ellison, C. G., & Fan, D. (2008). Daily spiritual experiences and psychological well-being among US adults. Social Indicators Research, 88, 247–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9187-2

Emmons, R. A., & Kneetzel, T. T. (2005). Giving thanks: Spiritual and religious correlates of gratitude. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 24, 140–148.

Espinola, A., & Badrinarayanan, V. (2010). Consumer expertise, sacralization, and event attendance: A conceptual framework. Marketing Management Journal, 20(1), 145–164.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

Fredrickson, B. L., Boulton, A. J., Firestine, A. M., Van Cappellen, P., Algoe, S. B., Brantley, M. M., Kim, S. L., Brantley, J., & Salzberg, S. (2017). Positive emotion correlates of meditation practice: A comparison of mindfulness meditation and loving-kindness meditation. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1623–1633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0735-9

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M. A., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. M. (2008). Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1045–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013262

Fredrickson, B. L., Mancuso, R. A., Branigan, C., & Tugade, M. M. (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 24(4), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010796329158

Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Gross, J. J., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–24). Guilford Press.

Haidt, J. (2003). The moral emotions. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of affective sciences (pp. 852–870). Oxford University Press.

Joye, Y., & Verpooten, J. (2013). An exploration of the functions of religious monumental architecture from a Darwinian perspective. Review of General Psychology, 17(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029920

Kim-Prieto, C., & Diener, E. (2009). Religion as a source of variation in the experience of positive and negative emotions. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271025

Koenig, H., King, D., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Krause, N. (2009). Religious involvement, gratitude, and change in depressive symptoms over time. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19(3), 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508610902880204

Krause, N. (2016). Assessing supportive social exchanges inside and outside religious institutions: Exploring variations among Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks. Social Indicators Research, 128(1), 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1022-6

LaFrance, M., & Mayo, C. (1978). Cultural aspects of nonverbal communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 2(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(78)90029-9

Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Braithwaite, S. R., Graham, S. M., & Beach, S. R. (2009). Can prayer increase gratitude? Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 1(3), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016731

Myers, D. G. (2018). Religious engagement and living well. In J. P. Forgas & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), The social psychology of living well (pp. 137–160). Routledge.

Neumann, R., & Strack, F. (2000). “Mood contagion”: The automatic transfer of mood between persons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.211

Páez, D., Rimé, B., Basabe, N., Wlodarczyk, A., & Zumeta, L. (2015). Psychosocial effects of perceived emotional synchrony in collective gatherings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(5), 711–729. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000014

Pargament, K. I., & Mahoney, A. (2005). Sacred matters: Sanctification as a vital topic for the psychology of religion. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 15(3), 179–198. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr1503_1

Park, C. L., Currier, J. M., Harris, J. I., & Slattery, J. M. (2017). Trauma, meaning, and spirituality: Translating research into clinical practice. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/15961-000

Ramsay, J. E., Tong, E. M. W., Chowdhury, A., & Ho, M. R. (2019). Teleological explanation and positive emotion serially mediate the effect of religion on well-being. Journal of Personality, 87(3), 676–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12425

Saroglou, V., Buxant, C., & Tilquin, J. (2008). Positive emotions as leading to religion and spirituality. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760801998737

Sauter, D. (2010). More than happy: The need for disentangling positive emotions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409359290

Schneller, G. R., & Swenson, J. E., III. (2013). Talking to god: Psychological correlates of prayers of praise and gratitude. Christian Psychology, 39–50.

Smith, C. A., Tong, E. M. W., & Ellsworth, P. C. (2014). The differentiation of positive emotional experience as viewed through the lens of appraisal theory. In M. M. Tugade, M. N. Shiota, & L. D. Kirby (Eds.), Handbook of positive emotions (pp. 11–27). Guilford Press.

Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A. M., Piff, P. K., Cordaro, D., Anderson, C. L., Bai, Y., Maruskin, L. A., & Keltner, D. (2017). Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review, 9(3), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916684557

Sy, T., Côté, S., & Saavedra, R. (2005). The contagious leader: Impact of the leader’s mood on the mood of group members, group affective tone, and group processes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.295

Tsai, J. L., Miao, F. F., & Seppala, E. (2007). Good feelings in Christianity and Buddhism: Religious differences in ideal affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206296107

Van Cappellen, P., Saroglou, V., Iweins, C., Piovesana, M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Self-transcendent positive emotions increase spirituality through basic world assumptions. Cognition & Emotion, 27(8), 1378–1394. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.787395

Van Cappellen, P., Toth-Gauthier, M., Saroglou, V., & Fredrickson, B. (2014). Religion and well-being: The mediating role of positive emotions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9605-5

Van Cappellen, P., Saroglou, V., & Toth-Gauthier, M. (2016). Religiosity and prosocial behavior among churchgoers: Exploring underlying mechanisms. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 26(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2014.958004

Van Cappellen, P., Ladd, K. L., Cassidy, S., Edwards, M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2020). Documenting and measuring the effects of full-body postures associated with positive and negative affect. Manuscript Under Review.

Van Cappellen, P., Edwards, M. E., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2021). Upward spirals of positive emotions and religious behaviors. Current Opinion in Psychological Science, 40, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.09.004

Van Cappellen, P., & Edwards, M. E. (2021a). The embodiment of worship: Relations among postural, psychological, and physiological aspects of religious practice. Journal for the Cognitive Science of Religion, 6(1–2), 56–79. https://doi.org/10.1558/jcsr.38683

Van Cappellen, P., & Edwards, M. (2021b). Emotion expression in context: Full body postures of Christian prayer orientations compared to secular emotions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-021-00370-6

Van Cappellen, P., Cassidy, S., & Zhang, R. (2021). Religion as an embodied practice: Documenting the various forms, meanings, and associated experience of Christian prayer postures. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000412

Van Tongeren, D. R., Aten, J. D., McElroy, S., Davis, D. E., Shannonhouse, L., Davis, E. B., & Hook, J. N. (2019). Development and validation of a measure of spiritual fortitude. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(6), 588–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000449

Vishkin, A., Ben-Nun Bloom, P., Schwartz, S. H., Solak, N., & Tamir, M. (2019). Religiosity and emotion regulation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 50(9), 1050–1074. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022119880341

Vishkin, A., Schwartz, S. H., Ben-Nun Bloom, P., Solak, N., & Tamir, M. (2020). Religiosity and desired emotions: Belief maintenance or prosocial facilitation? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 1090–1106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219895140

Winkielman, P., Niedenthal, P., Wielgosz, J., Eelen, J., & Kavanagh, L. C. (2015). Embodiment of cognition and emotion. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, E. Borgida, & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Vol. 1. Attitudes and social cognition (pp. 151–175). American Psychological Association.

Winzer, L., & Gray, R. S. (2019). The role of Buddhist practices in happiness and health in Thailand: A structural equation model. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 411–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9953-z

Yaden, D. B., Haidt, J., Hood, R. W., Jr., Vago, D. R., & Newberg, A. B. (2017). The varieties of self-transcendent experience. Review of General Psychology, 21(2), 143–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000102

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Van Cappellen, P., Zhang, R., Fredrickson, B.L. (2023). The Scientific Study of Positive Emotions and Religion/Spirituality. In: Davis, E.B., Worthington Jr., E.L., Schnitker, S.A. (eds) Handbook of Positive Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10274-5_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10274-5_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-10273-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-10274-5

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)