Abstract

One essential prerequisite for successful agile retrospective sessions is to accomplish a psychologically safe environment. Creating a psychologically safe environment for the co-located team is challenging. Further, it becomes more demanding with online agile retrospective teams. Literature sheds little light on creating a psychologically safe online environment for conducting agile retrospectives. Our study aims at addressing this knowledge gap and asks the research question: how does the usage of online tools influence psychological safety in online agile retrospectives? A single case study was conducted with a major software company’s Research and Development team. We analysed a recorded online retrospective session of the team to identify patterns of the usage of online tools associated with the online meeting platform they used and how that usage influenced the psychological safety level of the team. Our findings show that retrospective participants are psychologically safe if they share opinions, make mistakes, raise a problem, ask questions, and show consent using online tools. Our study contributes online tools that influence psychological safety factors, corresponding levels and behaviours.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Practising agile retrospectives helps the participants to reflect & learn from the experience [20], be more collaborative and contribute to work [18]. Also, it outlines the problems in workflow, makes transparent the work process [20] and overcomes efficiency loss challenges (rise in customer requirements, product complexity and prevention from competitive pressure) [6]. The new normality has pushed agile retrospectives in an online environment [4].

A psychologically safe environment is one key prerequisite for successful agile retrospective sessions, as indicated in the Prime DirectiveFootnote 1, widely embraced by agile software development teams. Safety is a state of mind that lets human beings sense their protectiveness from danger [31]. Psychological safety is a common belief where individuals or participants feel mentally and emotionally safe and willing to share their opinions with others in a group [8, 16]. It ensures participants feel included, can be themselves and enhance their work engagement within a team [16]. Psychologically safe team participants are inclined to be efficient and act responsively in the meetings. They are actively collaborating, contributing and helping their peers to solve problems [8, 9, 16].

While it is challenging to create a psychologically safe environment when software development teams are co-located, it becomes more demanding when agile retrospectives are conducted fully online. In online agile retrospectives (OARs), team members use tools provided by the online meeting platform to communicate. The online tools include video or teleconferencing, breakout rooms, chat and digital boards [10, 29]. Video or teleconferencing tools offer good support to run the online session [17]. The usage of these online tools during OARs can play a vital role in the psychological safety level of a team.

For example, a participant could use an audio or chat window to express opinions [9] on other participant’s opinions about What went well? What did not go well? and What could be done? to obtain improved sprints [18]. Doing so reveals that the participant is psychologically safe, feels included, and contributes to the team. Then a vote or emoji as an online tool allows a team member [12] to express decisions and emotions about the sprint. In a parallel and efficient way, while the participant is speaking during the OAR, a team member could use (raise hand  ) [9] to ask a question or raise a problem [1]. It provides the team to reflect, learn and express faster about the sprint [19] and ensures that participants are psychologically safe [16]. Whereas often, the unsafe participants are hesitant to express themselves. However, they can be anonymous and express their emotions with votes or emojis.

) [9] to ask a question or raise a problem [1]. It provides the team to reflect, learn and express faster about the sprint [19] and ensures that participants are psychologically safe [16]. Whereas often, the unsafe participants are hesitant to express themselves. However, they can be anonymous and express their emotions with votes or emojis.

Few studies mentioned psychological safety explored during online meetings. A software engineering study mentions psychological safety in teams and the norm clarity. The paper outline importance of adopting various norms that could contribute to a safe psychological ambience [23]. Also, a recent study describes psychological safety impacts on agile software development team performance. It might be either directly or indirectly through team reflexivity [3]. Still, there is a lack of studies investigating psychological safety in OAR.

Hence, the research questions formulated for this study is: RQ: How does the usage of online tools influence psychological safety in online agile retrospectives?

The paper is structured as follows. Section two describes the online agile retrospective, psychological safety levels, behaviours and factors. Also, the online tools influence the essence of psychological safety in online meetings. Then in section three, we describe software company information, the data collection and analysis procedure. Section four findings outline the five stages of OAR. In each stage, we found the usage of online tools that influences psychological safety factors, corresponding levels, and behaviours. Section five discusses the specificity of online agile retrospectives, including the meeting content conducted with online tools. Section six concludes the study with the inclusiveness of online meetings and their linkage to psychological safety as an interesting future study.

2 Background and Related Work

2.1 Online Agile Retrospective (OAR)

The idea of conducting a retrospective with participants is to collect information and notify those areas that need closer attention [18, 19]. Hence, that improves the team’s productivity and performance [20]. OAR help participants acquire knowledge gaps existing in the sprint before the next learning sprint begins [4] and insights about the learning activities [14]. During a retrospective session, the objectives or tasks are re-evaluated and then outlined in front of participants before the next iteration [18, 26], which leads to an improved product or service development life cycle [19]. Online retrospective participants use video/teleconference channels to contribute to the reflection of the iteration with other participants. The participants also share the time, location and duration of the retrospective [26]. A team can learn from the experience and share learning with other participants [20]. In retrospect, asking questions and raising a problem is common to learn from other participants [18]. One participant to facilitate the meeting must be present during the retrospective. They help to moderate the communication between the satellite participants [26]. A crucial thing to note during the OAR is to schedule it in advance. OAR is planned previously in online settings, as participants could vary with the working hours and time zones [4]. Online retrospectives cannot be very spontaneous, as different time zones could vary in hours, and the setup of video/teleconference is mandatory. The online environment could require time to set up the internet and other online tools [26]. In OAR, participants must contribute to work by sharing an opinion or asking a question about the previous iteration cycle [11]. In doing so, the participant should feel safe presenting the work [31] and help peers learn better about the iteration [19].

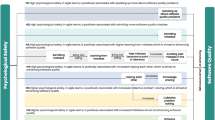

2.2 Psychological Safety

Psychological safety is a shared or common belief where individuals are willing to share opinions, feedback, information, mistakes, raise a problem, ask a question, or even disagree with participants without fear [5, 8, 9]. Figure 1 provides psychological safety levels and behaviours. It is an unsaid belief within participants about feeling safe to be (1) included, (2) learn, (3) contribute, (4) challenge the status quo [5] while working with others.

-

1.

Included: This initial psychological safety level describes the acceptance of the participant to the workgroup, team or environment gathered by various humans who are willing to be together. Once a participant is safe to include, he/she gains acceptance or admittance to the group and attention from others. Feeling included is the opposite of being ignored or rejected by others who are willing to be together in the same environment [5, 8, 16].

-

2.

Learn: The second level is the feeling of being safe to engage and learn with others. Participants need to be heard and engaged by asking about some information, experimenting or making mistakes to discover something. This learning passage helps participants harness confidence, independence, and resilience [5, 8].

-

3.

Contribute: Compared to the previous level, participants are more active with others and observed as qualified contributors. They demonstrate competence in the environment and usually are free to contribute. Participants expected contribution is visible at this level [5, 8].

-

4.

Challenge the status quo: At the final level, a participant is confident enough to challenge the ongoing situation in the environment. It requires courage and proper time to speak the truth when something needs to change or alter the current situation. Participants at this level are confirmed about the facts and could rank themselves in a creative process of contribution [5, 8].

2.3 Psychological Safety Factors

Four factors influence psychological safety: trust, mutual respect, constructive response and confidence [7, 8].

-

Trust: It is a situation when participants have faith in peers. It is the mental attitude of participants that provides a comfort zone for others [7, 8]. A study by Duehr et al. [6] claims that trust among participants provides clarity and understanding of work objectives during an OAR. Also, trust leads to increasing the transparency and contribution of information.

-

Mutual respect: This factor leads to caring for each other and encourages a psychologically safe environment. It might be that there are issues inside a team [3]. However, mutual respect provides being tolerant of dealing with each other’s responses and behaviours [7, 8].

-

Constructive response: A response provided on the mistakes or errors that help a participant improve without feeling discouraged. Errors are typical but should not lead to rejection and discouragement in a team [7, 8].

-

Confidence: It is a clear state of mind believing someone or something is correct, even if the evidence is entirely lacking. It is the ability to assure that something is correct [7, 8].

With the factors mentioned above, participants are willing to be open about the actions they intend to consider and have a feeling of invulnerability in the group. They can share their beliefs without being scared. As a result, information and knowledge are transparent and circulate in a group [5, 7, 8].

2.4 Online Tools

Online meetings are comfortable if participants know or have met each other in person previously. There is a feeling of being connected to other peers, as faces and characters exist behind the names displayed during online meetings. The trend of meeting with online participants is increasing after the pandemic [1, 10], which increases the use of online tools [22]. Below is a list of tools embedded in online meeting platforms that may influence psychological safety in an online environment [9].

-

Video: The video is one of the known tools used during an online conference [1, 10]. It replaces the physical essence of face-to-face conversation and creates an environment that leads to enhanced interaction with the participants [9, 28, 29]. Some participants blur the background or adapt to a banner or theme behind the face because participants do not want to share the room or background [22]. Video dramatically relies on the internet bandwidth. Breaking down or slowing down the internet, meaning participants can see the held faces [29]. A speaker should be encouraged to turn on the video and, if the rest participants prefer, should be allowed to switch it off [9]. Video without audio could be challenging to decipher [25] in the case of silence during the meetings. Participants in the meeting could hold silent for a few seconds [15], and then someone brave enough to break it and present their thoughts. Otherwise, a facilitator should be present at the moderate session [9]. The facilitator could turn on/off the video and the audio to make it comfortable for other participants.

-

Audio-only: Audio helps make the session interactive during the meetings [10]. Crucial is paying acute attention to the speaker to avoid misinterpretation of what the speaker wants to express [28]. For example, a raised question could clear doubts if there is a misunderstanding. Participant’s must not misjudge the silence when there is no audio. A participant’s silence could mean either Yes or No. To overcome, a checkmark is helpful during the meetings [9, 12].

-

Checkmark (Yes/No): Participants who prefer to be silent could use the checkmark to present their opinion. Usually, the tick (

) sign represents the Yes, and the cross (X) sign represents No. These checkmarks act as an agreement or disagreement with the presenter’s voice. However, checkmark has a problem; fully agreeing or disagreeing with speakers’ information. Checkmark is not helpful to present partial agree or disagree opinions. To overcome this, polls or chat should be used [9].

) sign represents the Yes, and the cross (X) sign represents No. These checkmarks act as an agreement or disagreement with the presenter’s voice. However, checkmark has a problem; fully agreeing or disagreeing with speakers’ information. Checkmark is not helpful to present partial agree or disagree opinions. To overcome this, polls or chat should be used [9]. -

Polls/Votes: This online tool improves the shared feedback from participants [29]. However, some participants could be afraid of displaying their names in the poll. In order to make these psychologically safe, anonymous polls/votes provide a fair outcome and valid opinion [9, 12].

-

Chat: Chat is an excellent tool for interaction (such as the risk of asking a question, expressing an opinion or raising a problem). However, messages could also distract from the speaker’s conversation if the text is too long. Messages could become spam if they are redundant and not precise. Hence, participants should be aware of the length and quality. Chat should be applied if it is needed to share the information [9].

-

Breakout rooms: Breakout rooms inside the online meeting provoke natural and safe conversation [29]. These rooms are safe spaces where it is possible to take the risk of raising a problem or making mistakes with a small group and seek feedback. A structured breakout room [29] involves participants interacting about a specific task or topic [9]. Often peers are comfortable and feel included in breakout rooms. Also, in breakout rooms, participants might know peers and could test, validate, and re-build the concepts [9].

-

Emoji (e.g., raise hand

): Emoji functions to interact (raising a problem, opinion or seeking information) with peers. However, participants should think wisely before using them. At some point, an emoji could also create an insecure environment at some speaker’s presentation [9, 12].

): Emoji functions to interact (raising a problem, opinion or seeking information) with peers. However, participants should think wisely before using them. At some point, an emoji could also create an insecure environment at some speaker’s presentation [9, 12]. -

Digital board: Digital boards are online tools that let participants comment, chat, reflect and share opinions on the task [24]. For example, Parabol, Retrium [27], Atlassian, or Mural digital boards conduct agile retrospectives with remote participants supporting psychological safety.

As far as the authors are aware, no study focused on how the usage of online tools can influence the psychological safety of participants of online agile retrospectives. Our study aspires to address this knowledge gap.

3 The Research Approach

A case study is an appropriate methodology to answer “how” research questions [30]. To answer our RQ, we conducted a case study of a research and development team of a sub-branch of a major multi-national software company (company name omitted due to anonymity agreement). The software company offers a solution for cybersecurity, business intelligence, enterprise resource planning, customer relationship management, and system and service management. This sub-branch also helps other companies in the digitalization and innovation processes.

3.1 Data Collection

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic situation, we collected the data in an online settings. Table 1 presents the data collected in the case study and the data collection methods used.

-

Session (A): It is an unstructured group interview session conducted to collect contextual information about the software company, the team studied and how they are doing agile software development. This recorded session displays various questions and answers with the product manager and two leaders.

-

Session (B): It is a complete recording of an OAR session of the team at the end of one Sprint. The recording was done by the team and handed over to the researchers. The researchers were not present at this OAR session.

-

Session (C): It is an unstructured interview session with the product manager who directly manages the studied team. This session helped clarify the data gathered in the previous two sessions.

3.2 Data Analysis

We found various instances of interest from OAR showing the psychological safety of the bracketing technique as a research approach. It is a technique that has been applied increasingly in qualitative research studies [13]. It is the art of picking various episodes of interest from an event and probably, clustering later those instances into another event [13, 21]. It is helpful where key sections of importance exist in the entire event. They could be diverse and assorted but are topics of interest. The researcher should describe precise breakpoints for the different instances of the event. The instances found were time-stamped and coded into transcripts using NVivo12 software, a qualitative data analysis software.

-

Session (A): This session revealed insights about the work routines of the studied team and agile practices involved in the online settings. The company performs various agile practices; sprint planning, standup, retrospective and low-level design meetings. The research and development participants are involved in OAR. Often, the service support members also take part in the OAR. The retrospective lasts between 60 to 75 min. The software company uses the digital board Parabol and the Microsoft Teams for conducting OAR, as shown in Fig. 2.

-

Session (B): We found various thematic codes corresponding to OAR. It is a method of systematically identifying themes or patterns across qualitative data [2]. The thematic codes trust, mutual respect, constructive response, confidence, opinion, information, facilitator, included and contributed emerged under the psychological safety and icebreaker, reflect, group, vote and discuss under the stages of OAR. Under online tools, we found many thematic codes such as video, screen-share, audio, text and emoji.

-

Session (C): While analysing the OAR, various questions occurred about the participants, process and OAR. All notes questions, later in the interview, were asked “Who was the person leading the retrospective meeting? If he is not a scrum master, then? Who all are involved in the software development?” to the project manager.

4 Psychological Safety in OAR

Parabol is an agile meeting tool that provides a digital board helping remote participants to connect, reflect, and monitor the work progress. The board consists of five stages, in sequential order: Icebreaker, Reflect, Group, Vote, and Discuss, shown on the left side of the Parabol (see Fig. 2). The participants start with the Icebreaker stage and conclude the retrospective with the Discuss stage.

4.1 Icebreaker Stage

It is a warm-up stage. In this stage, all participants answer one from the 237 icebreaker questions provided by the digital board. The facilitator shared the screen using Parabol and Microsoft Teams (Fig. 3), where the question “What is a food, smell, or sound that you associate with where you grew up” was displayed. Each participant got a few minutes to answer this question, one by one. During this stage, the participants had the video off, their avatars or photos with their names were visible on the shared screen, and they used audio for verbal responses. We identified the following instances of interest in this stage.

Concerning psychological safety, first-level included. All participants had the feeling of being accepted to OAR. One participant verbally raised a problem- “sorry, can anyone please share the Parabol link with me? My link is not working”. The facilitator then shared an opinion- “yes” and used text to re-send the link. This behaviour gives the participant a safe feeling of being included at the OAR. Also, peers show mutual respect by waiting till everyone is on-board. After a few seconds, the same participant realises that a technical problem exists. The participant boldly explained the information- “I have reset the password and laptop, but still have some technical issues”. The online tool was not working. However, it was essential to respect the OAR schedule and other participants. Hence, the Facilitator gives a constructive response and shares the opinion- “I think we can start the meeting, and once you join” Parabol, “you can be in the Icebreaker question list”.

In some instances, psychological safety could be challenging. A participant should not ignore and must reply to the facilitator’s question if asked. Regarding psychological safety level included. A participant during the OAR did not answer the question. The facilitator called a participant’s name during his turn “we cannot hear you if you are talking”. The participant’s photo with the name was visible on the shared screen, but no replies. It breaks the trust and mutual respect when peers want to contribute during OAR. To overcome if the participant cannot answer, should share information, and raise the issue by chat or breakout room to convey the problem. When there was silence for a short while, and participant did not responded. Another participant shared information- “he is busy, he is in another meeting, but not attending this meeting” using audio.

Concerning psychological safety, third-level contribute using available online tools. The facilitator takes a significant responsibility to run the OAR. Also, ensure that every participant is online connected to Parabol and contributes- “Please let me know when you finish. Thank you”.

A participant involved self-referential humour that created a joyful atmosphere during the OAR. Sharing a joke about oneself could make participants laugh. Concerning psychological safety, level contribute. A participant verbally shared information- “I hope it is not a cliche, I still enjoy it”. The facilitator shared the opinion- “It is a bit of a cliche, I would say,” and in return, the participant laughed at the opinion- “Haha”, and other participants also laughed “Haha”. Later, other participants shared similar information- “The smell of fertilisers from the cow and the sound of (cows and cock) come at 4:00 am when you still have one more hour to sleep, but you cannot sleep. Haha”. One participant used another online tool, which was a funny image or picture, to share an opinion in the chat window.

Concerning psychological safety level contribute. There was a voice break instance when a participant spoke and shared the information about the icebreaker question. However, the other participants and facilitator could not able to hear. Hence, the facilitator asked, “What?What?..”. To reply the participant shared information via text in the chat- “I am facing a sudden power cut and my laptop battery has only 30 min left” and sorry, restarting. Peers showed trust mutual respect and gave a constructive response via text. Some used a checkmark and emoji (Thumbs-up or like:  ) to give a constructive response to the participant’s message.

) to give a constructive response to the participant’s message.

4.2 Reflect Stage

Compared to the previous stage, this stage was challenging to analyse. Each participant must carry an individual reflection about the previous iteration cycle without interaction. Participants used the digital board and wrote down their thoughts on small (post-it notes) cards. Hence, silence existed during this stage. OAR was ongoing on Microsoft Teams, with avatar/photo with name visible on the facilitator shared screen. Concerning psychological safety level included. The facilitator shared the opinion- “when you finish writing, please click on the button so that we can move on to mark the end of this stage and start the next one”. It showed a sign of psychological safety where all participants were included and shared reflection.

4.3 Group Stage

The group stage is similar to the previous stage. Less audio interaction. The facilitator shared a screen with the digital board, which displayed all the inputs. The digital board displayed text inputs and the facilitator clustered them into four columns (Plus, Delta, Ideas, and Flowers) evident from Fig. 4. Each column had a question or topic (What worked well? Things to improve, New things to introduce and Thank the team members who helped) that participants addressed. With respect to psychological safety level contribute. The participant text was written on various cards and placed under the four columns. The facilitator sought the participants feedback by asking the question- “Should we put the..” digital post-it cards “in the sprint? or..”. Some participants contributed by giving their consent- yes and some replied by remaining silent and letting the facilitator continue to arrange the cards under the columns.

4.4 Vote Stage

Participants vote at this stage. The facilitator shared the screen with all the voting options and used audio as an online tool to explain the cluster of cards one by one. The participants used emoji (thumbs-up or like: ) on the digital post-it cards to vote. A negative factor is a finger-pointing or being accused, is not a good practice during OAR. It tampers psychological safety. If done, participants might feel unsafe and less motivated to continue the OAR. Regarding psychological safety, level contribute. A participant finger pointed and asked- “who did not vote? It is exactly one person who did not vote? Maybe..?” and the peer replied, “I voted”. Again the question was raised. “OK, if you voted, who did not vote?”. There might have been several reasons not to vote. Probably not aware of the functionalities of the online tool, or someone may be new to an online platform. Later a participant shared the feedback- “maybe someone did not know how to vote. Hence, this resulted in few votes. It is a constructive response that made OAR psychological safe.

) on the digital post-it cards to vote. A negative factor is a finger-pointing or being accused, is not a good practice during OAR. It tampers psychological safety. If done, participants might feel unsafe and less motivated to continue the OAR. Regarding psychological safety, level contribute. A participant finger pointed and asked- “who did not vote? It is exactly one person who did not vote? Maybe..?” and the peer replied, “I voted”. Again the question was raised. “OK, if you voted, who did not vote?”. There might have been several reasons not to vote. Probably not aware of the functionalities of the online tool, or someone may be new to an online platform. Later a participant shared the feedback- “maybe someone did not know how to vote. Hence, this resulted in few votes. It is a constructive response that made OAR psychological safe.

4.5 Discuss Stage

In the final stage of OAR, shown in Fig. 2 left side, participants discussed the previous stage’s context and the next iteration sprint. This instance existed in the “cross-team” issue cluster. Concerning psychological safety, level challenge. One participant challenged the current situation of the cross-team tasks. The facilitator had a shared screen where participant’s avatar or photo with their name was visible with Parabol. With confidence, the participant raised the problem using audio- “I really did not like” and shared the opinion- “Probably it is a controversial opinion” about the situation, but “it would better if it is done in the other way”. The facilitator appreciated, “I like your opinion, we could try to handle it in this way”. While another participant joined the conversation and, with confidence, showed the consent and shared the opinion- “In the previous sprints, we handled the situation in this way. The wrong part was that we did it all in the same sprint. However, many jobs were there to do. We were forced to work across the team”. Finally, to finish the conversation, the first participant ended up with constructive response and shared the opinion- “OK, in this context. I agree” to you.

Regarding psychological safety, level contribute. The facilitator presented three clusters of digital cards. First, a discussion with 21 cards about the “cross-team” cluster. Then the “sprint” cluster with 16 cards and finally “thanks (miscellaneous)” was clustered with 13 cards. The facilitator read aloud each card’s content and participants shared their opinions through text and emojis.

As evident from Fig. 2, different emojis heart  , smiley face

, smiley face  , neutral face

, neutral face  , sad face

, sad face  , flowers bouquet

, flowers bouquet  , fire

, fire  , rocket

, rocket  peers responded to the facilitator’s question, “Do you want to add something to the cluster of cards? If you think something is underestimated”. One participant shared an opinion using audio, “I think maybe on..card, where i wrote..I work a lot using..” and another participant with a constructive response, shared feedback- “I think it is good idea to add”. Finally, the facilitator shared the opinion- “OK, I will add a task card”.

peers responded to the facilitator’s question, “Do you want to add something to the cluster of cards? If you think something is underestimated”. One participant shared an opinion using audio, “I think maybe on..card, where i wrote..I work a lot using..” and another participant with a constructive response, shared feedback- “I think it is good idea to add”. Finally, the facilitator shared the opinion- “OK, I will add a task card”.

4.6 Summary

Psychological safety is essential for every workplace. We obtained several instances of interest by bracketing technique as a research approach. The finding answers the rq: how does the usage of online tools influence psychological safety in online agile retrospectives? Table 2 presents online tools which influence psychological safety during OAR. The team preferred video (screen share, avatar or photo with name), audio, chat (text, image or picture) and emoji as online tools to moderate the OAR. Instead of video, participants were interested in keeping the camera off and putting the avatar or photo with the name. The table also presents self-referential humour, ignoring, silence, and finger-pointing are the psychological factors and agree as consent or psychological behaviour that participants practised during OAR.

-

It is vital to intermingle with the participants and invest some social time cultivating psychological safety. Since participants are online, it is crucial to start the online retrospective by revealing some fun facts for a team to know peers’ emotional context. The use of an online tool provides a list of icebreaker questions where each participant can intermingle by responding to one question and knowing the team and their emotions.

-

The team that conducted OAR did not have a scrum master. One person among the participants took the role of the facilitator and hosted the OAR. We found out that the digital retrospective board, an online tool, allow a structured and efficient way to conduct a retrospective, although the team was missing the scrum master. If the scrum master is not present to moderate, other participants can become the facilitator using the digital board to run the OAR. The retrospective board was psychological safe and included different stages of agile retrospectives.

-

We also found that the facilitator sharing screen enhances the team’s willingness to share emotions and contributions during OAR. When the team members see anonymous input from peers on the digital cards, they are more motivated to share contributions without fear. Being anonymous gives the team freedom, confidence, and free to express themselves.

-

We discovered it is more convenient for a facilitator to moderate and give more contributions without hassles using an online tool. The facilitator was concentrated and involved with the participants due to online functionalities. For example, using digital post-it notes and commenting on them with participants’ emotions and moods saved the facilitator’s time. Hence, the facilitator invested more time and had feelings of being included during OAR.

-

An efficient time control watch is visible on the shared screen with online tools. In this way, each participant’s input is given equal importance and considered. Hence, allowing participants a feeling of being included in OAR. This psychology helps the team to have a control discussion mechanism.

5 Discussion

Participant’s interaction matters most when online with peers [10, 28], which helps influence psychological safety during OAR. Interesting to discuss is the silence that might occur during the meetings. In terms of psychological safety, participants’ audio and written text messages are easy to decipher, but silence being a participant online is challenging. Silence could be consent that is either yes or no. Short or long enough, silence online could mean differently [15]. Peers might psychologically feel ignored during OAR. A long silence could be awkward [15]. However, it could be that the participant is taking time to think during the reflecting stage 4.2. Whereas during the icebreaker stage,4.1, the participant was silent and, without informing, was busy in another meeting. To overcome if the participant is busy, should share information via online tools such as chat or breakout room to convey the problem to the facilitator.

On the other hand, interaction through audio or writing is crucial [28] to realise psychological safety. Misinterpretation about silence might occur during online meetings [15].

Also, if long enough silence exists, the facilitator could raise a proactive question, what do you think about the situation? [9] to encourage interaction. Online tools do give support to factors and raise the interaction among participants. Suppose participants are introverted and do not like to raise their opinions via audio as an online tool. The team repeated the pattern of using emojis as an online tool during the OAR. Emoji could be a powerful way to share the contribution and speak aloud to the participant’s opinion. Participants were able to present their emotions during the OAR without interrupting the speaker.

Video is one of the most applied online tools [10] during meetings [1], influencing psychological safety [9]. Instead of video, participants with a photo can use audio or other online tools to lead an effectual interaction by sharing opinions and asking questions. An interesting thing to notice was that all the participant’s video was off for the entire OAR. Still, the participants showed they are psychological safety by challenging the status quo during the OAR.

Threats: We analysed one OAR with a single case, the external threat to our study. To what extent does the proposed study apply to other participants involved in the online meetings. The internal threat to our study is the history of the participants. Previously, how much they were familiar or acquainted. Some might acquaint themselves as long time working colleagues who show trust and respect with peers. To overcome, pre-session gave us insights into the entire OAR process and its participants. The session involved the project manager and two teams leaders. Both of them have been working with the company for many years. Then we also did we did a post retrospective FAQ session 3.2 with the team leader, where we asked various OAR questions. We recorded and observed all three sessions thoroughly to know the in-depth phenomena of psychological behaviour of OAR participants. Further analysis of other company participants may be interesting, as switching to other agile software development practices and remote work might affect the various psychological behaviours.

6 Conclusion

OAR provides an opportunity for participants to learn, contribute, and discuss iteration cycles if the team feel psychologically safe. This study outlines how online tools influence psychological safety factors, corresponding levels and behaviours. Due to icebreaker questions, accessible digital inputs, anonymous emotion sharing, commenting, and online retrospective facilitation via structured five stages. For researchers, the study is helpful, as it serves as a base stone that guides psychological safety research focused on the online perspective. Further research could be considered the psychological safety levels, factors and online tools with other online meetings. For practitioners, participants could use the study during the online agile retrospective and other online meetings and see if they feel psychologically comfortable contributing and willing to share their learning.

References

Agusriadi, A., Elihami, E., Mutmainnah, M., Busa, Y.: Technical guidance for learning management in a video conference with the zoom and youtube application in the covid-19 pandemic era. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1783, 012119 (2021)

Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Thematic analysis. (2012)

Buvik, M.P., Tkalich, A.: Psychological safety in agile software development teams: work design antecedents and performance consequences. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.15034 (2021)

da Camara, R., Marinho, M., Sampaio, S., Cadete, S.: How do agile software startups deal with uncertainties by covid-19 pandemic? arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.13715 (2020)

Clark, T.R.: The 4 Stages of Psychological Safety: Defining the Path to Inclusion and Innovation. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Oakland (2020)

Duehr, K., et al.: The positive impact of agile retrospectives on the collaboration of distributed development teams-a practical approach on the example of bosch engineering gmbh. Proc. Des. Soc. 1, 3071–3080 (2021)

Edmondson, A., Mortensen, M.: What psychological safety looks like in a hybrid workplace. Harvard Bus. Rev. 3, 109 (2021)

Edmondson, A.: Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 44(2), 350–383 (1999)

Edmondson, A.C., Daley, G.: How to foster psychological safety in virtual meetings. Harvard Bus. Rev. 25 (2020)

Fauville, G., Luo, M., Queiroz, A.C., Bailenson, J.N., Hancock, J.: Zoom exhaustion & fatigue scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 4, 100119 (2021)

Feitosa, J., Salas, E.: Today’s virtual teams: adapting lessons learned to the pandemic context. Organ. Dyn. 50(1), 100777 (2020)

Frisch, B., Greene, C.: What it takes to run a great virtual meeting. In: Harvard Business Review (2020). https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-it-takes-to-run-a-great-virtual-meeting

Gearing, R.E.: Bracketing in research: a typology. Qual. Health Res. 14(10), 1429–1452 (2004)

Hulshult, A.: Using eight agile practices in an online course. J. High. Educ. Theor. Pract. 19(3), 55 (2019)

Isbister, K., Nakanishi, H., Ishida, T., Nass, C.: Helper agent: designing an assistant for human-human interaction in a virtual meeting space. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 57–64 (2000)

Kahn, W.A.: Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manage. J. 33(4), 692–724 (1990)

Karl, K.A., Peluchette, J.V., Aghakhani, N.: Virtual work meetings during the covid-19 pandemic: the good, bad, and ugly. Small Group Res. 10464964211015286 (2021)

Khanna, D.: Experiential team learning in software startups. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Agile Software Development: Companion, pp. 1–3 (2018)

Khanna, D., Nguyen-Duc, A., Wang, X.: From MVPs to pivots: a hypothesis-driven journey of two software startups. In: Wnuk, K., Brinkkemper, S. (eds.) ICSOB 2018. LNBIP, vol. 336, pp. 172–186. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04840-2_12

Khanna, D., Wang, X.: The buried presence of entrepreneurial experience-based learning in software startups. In: SiBW, pp. 30–39 (2018)

Langley, A.: Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad. Manage. Rev. 24(4), 691–710 (1999)

Lechner, A., Mortlock, J.T.: How to create psychological safety in virtual teams. Organ. Dyn. 100849 (2021)

Lenberg, P., Feldt, R.: Psychological safety and norm clarity in software engineering teams. In: Proceedings of the 11th International Workshop on Cooperative and Human Aspects of Software Engineering, pp. 79–86 (2018)

Masood, Z., Hoda, R., Blincoe, K.: Adapting agile practices in university contexts. J. Syst. Softw. 144, 501–510 (2018)

Raake, A., Fiedler, M., Schoenenberg, K., De Moor, K., Döring, N.: Technological factors influencing videoconferencing and zoom fatigue. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.01740 (2022)

Sureshchandra, K., Shrinivasavadhani, J.: Adopting agile in distributed development. In: 2008 IEEE International Conference on Global Software Engineering, pp. 217–221. IEEE (2008)

Topp, J., Hille, J.H., Neumann, M., Mötefindt, D.: How a 4-day work week and remote work affect agile software development teams. In: Przybyłek, A., Jarzębowicz, A., Luković, I., Ng, Y.Y. (eds.) LASD 2022. LNBIP, vol. 438, pp. 61–77. Springer, Cham (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94238-0_4

Tree, J.E.F., Whittaker, S., Herring, S.C., Chowdhury, Y., Nguyen, A., Takayama, L.: Psychological distance in mobile telepresence. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 151, 102629 (2021)

Vandenberg, S., Magnuson, M.: A comparison of student and faculty attitudes on the use of zoom, a video conferencing platform: a mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 54, 103138 (2021)

Yin, R.K.: Case Study Research: Design and Methods, vol. 5. Sage, Thousand Oaks (2009)

Zhang, Y., Fang, Y., Wei, K.K., Chen, H.: Exploring the role of psychological safety in promoting the intention to continue sharing knowledge in virtual communities. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 30(5), 425–436 (2010)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Khanna, D., Wang, X. (2022). Are Your Online Agile Retrospectives Psychologically Safe? the Usage of Online Tools. In: Stray, V., Stol, KJ., Paasivaara, M., Kruchten, P. (eds) Agile Processes in Software Engineering and Extreme Programming. XP 2022. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, vol 445. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08169-9_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-08169-9_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-08168-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-08169-9

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)

) sign represents the Yes, and the cross (X) sign represents No. These checkmarks act as an agreement or disagreement with the presenter’s voice. However, checkmark has a problem; fully agreeing or disagreeing with speakers’ information. Checkmark is not helpful to present partial agree or disagree opinions. To overcome this, polls or chat should be used [

) sign represents the Yes, and the cross (X) sign represents No. These checkmarks act as an agreement or disagreement with the presenter’s voice. However, checkmark has a problem; fully agreeing or disagreeing with speakers’ information. Checkmark is not helpful to present partial agree or disagree opinions. To overcome this, polls or chat should be used [ ): Emoji functions to interact (raising a problem, opinion or seeking information) with peers. However, participants should think wisely before using them. At some point, an emoji could also create an insecure environment at some speaker’s presentation [

): Emoji functions to interact (raising a problem, opinion or seeking information) with peers. However, participants should think wisely before using them. At some point, an emoji could also create an insecure environment at some speaker’s presentation [