Abstract

While a PhD degree is often considered the first necessary step to an academic career, since 2010 only a small fraction (less than 10%) of doctoral graduates obtained a position in academia within six years of the award of their degree. While we do not have information on their labour market outcomes, we can examine the determinants of this transition in order to study whether entry to an academic job is becoming more difficult. We merge three national administrative data archives covering completed doctoral degrees, postdoc collaborations and new hirings to academia (mostly assistant professor level). We find a decline in appointment probability after 2010, due to the hiring freeze imposed by fiscal austerity. We find, also, that a PhD degree and postdoc experience have a positive effect on the probability of obtaining a position in academia, while being a woman or being a foreign-born candidate has a negative effect. We found no evidence of career disadvantages for candidates from Southern universities.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Traditionally, in Italy, academics are respected. In a famous book, entitled Baroni e burocrati. Il ceto accademico italiano (Barons and bureaucrats: The Italian academic class) Giglioli (1982) compares academics to mandarins whose power over society was legitimized by selective access. In the occupational rankings proposed originally by DeLillo and Schizzerotto (1985), academics (docenti universitari) scored 80.91 out of 100 and in a recent update scored similarly highly (81.13) (Meraviglia & Accornero, 2007), equivalent to a manager (dirigente) in the public administration. However, almost contemporaneous scandals related to public competition for university professorships raised doubts among the public over the fairness of the selection process for entry to an academic profession (Perotti, 2008).

International comparisons (Janger et al., 2013), accounting salary levels, quality of life, doctoral degree, career prospects, research organization, balance between teaching and research, funding and probability of working with high-quality peers, suggest that Italy is one of the least attractive countries at entry to an academic career.Footnote 1 It is difficult to compare data on salaries at entry: a survey conducted on behalf of the European Commission (2007) reports that the average remuneration of an Italian researcher is 34.120 euro in PPP, against the EU-25 average of 40.126 euro and an equivalent US entry salary of 62.793 euro.Footnote 2

Such a large wage differential, combined with the increasing career uncertainty revealed by our empirical analysis, might explain the brain drain among Italian researchers. Nascia et al. (2021) show that Italian researchers working abroad achieve faster career progression than those researchers who remain in the Italian system and they provide evidence of low confidence among Italian researchers of career advancement in Italy. The authors document how the decline in the number of university positions (20% over the period 2009-16) has translated into delayed career advancement and an increase in the average age of university staff. The main driver of migration is the perception that promotion abroad is based more on merit than on seniority-based progressions. This increases the salary differential and works against a domestic career.Footnote 3 The initial transition from doctoral graduate to assistant professor (from R1 to R2 in the OECD ranking) takes 5.5 years in Italian universities and 4.3 in universities abroad.

This evidence is supported by the increasing proportion of doctoral graduates who migrate abroad after finishing their degree (Istat, 2018): in 2018, 15.9% of graduates who obtained their PhD degree in 2012 were living and working abroad, and the percentage for those who were awarded their degree in 2014 was 18.5. Among those doctoral graduates who chose to remain in Italy, only 10.2% were employed as academics six years after the award of their degree, whereas among those who moved abroad, 25.9% achieved a position in academia.Footnote 4

If doctoral graduates decide not to follow an academic career, where do they end up?

Passaretta et al. (2019) use Istat survey data on two cohorts (PhDs obtained in 2004 and 2008)Footnote 5 to show that academic reformsFootnote 6 and the 2009 economic crisis coincided with decreasing employment in academia and increasing chances of having a fixed-term contract, being employed abroad and working in research-related occupations outside academia. In particular, they show that five years after graduation, the proportion of doctoral graduates with tenured positions in academia (i.e. excluding postdocs and temporary assistant professors—ricercatore di tipo A) declined from 36% in the 2004 cohort to 29% in the 2008 cohort.

Ballarino (2020) provides new evidence about the social origins and occupational outcomes of doctoral graduates in Italy. He takes master’s (MA) degree holders as the reference and shows that, after controlling for an equivalent time from degree award, doctoral graduates do not achieve higher incomes and have no greater employment probability. Almalaurea (an agency that interviews graduates on behalf of universities) data for 1999–2009, show that the doctoral graduates’ academic employment probability declines by 0.7% per year, but increases by 1.4% for employment in the private sector. This is consistent with the reduced employment opportunities in academia over that period and, especially, in the social science and humanities disciplines.

The existing evidence supports the conclusion that Italian PhDs are gradually discouraged from entering academia in Italy and are diverted towards foreign universities and/or the domestic private sector. However, the comparative decline in employment of doctoral graduates in universities could be due, also, to use of adjunct professors (professori a contratto) to cover teaching demand promoted by the increase in the courses offered by Italian universities, especially those less well-funded universities in the South of Italy (De Angelis & Grüning, 2020).

The decline in academic occupation opportunities is attributable mainly to the recruitment restrictions imposed on Italian universities: Italian budgetary law restricted new hirings to 20% of past retirements in 2012–2013 and then raised new hirings to 50% in 2014–2015, 60% in 2016, 80% in 2017 and 100% in 2018 (Corte dei Conti, 2021, p. 128). Table 1 presents employment in Italian universities and shows relative stability among teaching staff (+2.2% over 4 years), a marked decline in assistant professor entry level (−8.8%) and an increase in temporary positions (+10.9% for adjunct professor, +3.7% for postdoc, +12.9% for research assistants).Footnote 7 If we examine geographical variations (available in the original source) the picture is starker: based on the ratio of postdocs to assistant professors to proxy for the increased precariousness of academic jobs, this ratio changes from 0.92 to 1.0 in Northern universities and 0.31 to 0.35 in Southern universities. This implies that there are more (temporary) opportunities created in the North compared to the South, likely due to better availability of research funds in the former.

Within this general framework, we study entry to academic jobs since 2010. We address two questions: (1) whether gender, discipline and location affect the decreasing entry opportunities and (2) whether obtaining a postdoc position is advantageous for entry probability.

Our work extends the analysis conducted by Coda and Geuna (2020) who analyse the academic progression of graduates awarded their PhD degree by an Italian university, over the period 1983–2006 (before the hiring freeze and the reform to assistant professor positions). Doctoral graduates who pursued an academic career were identified by matching names to research fields using the list of academics active in Italian universities in the period 1990–2015. The most relevant conclusion is that, in the first 20 years (up to 2003) almost one third (33%) of Italian PhD degree holders were employed in academia (as assistant, associate or full professors). This excludes those awarded their PhD degree by a foreign university (this information is not included in the available databases) and includes the effects of the legal requirement for a PhD degree in order to apply for an assistant professorship (law 210/1998). Coda and Geuna provide various disaggregations (by gender, research field and geographical mobility): the share of PhDs pursuing an academic career is highest among men working in the fields of economics and statistics (52.2%) and lowest among women in medicine (19.2%).Footnote 8 The average time required for transition from PhD degree award to assistant professor is 4.5 years, with a declining trend between 1986 and 1996 and 1997 and 2006.

Our paper extends their analysis in several ways. First, we consider a more recent period: we use data on PhD degrees awarded during 2006–2017 and academic posts attained between 2010 (or earlier) and 2019. The collaboration between ANVUR and MIUR provided access to the list of doctoral graduates, which avoided having to parse them from the Italian National Library in Florence, where PhDs were required to materially deposit a copy of their dissertation.Footnote 9 We were able to exactly match the databases using social security identifiers, which minimized the risks caused by homonyms. The data also allow us to consider both direct transitions (from degree award to professorship, which became less usual) and indirect transitions (from PhD degree to postdocs, and postdocs to assistant professorships, distinguishing between permanent and temporary positions, but not between tenure track and purely temporary positions). We were able, also, to take account of age and citizenship, and a more precise definition of field of study.

2 The Data

The data for the analysis come from three administrative archives, which are not inter-connected, although they are managed by the same agency (CINECA) on behalf of the Ministry of University and Research (MIUR). Each database contains basic information on the individuals included, that is, gender, age, country of birth, research field and university of study/work. Our objective is to study the academic career paths of Italian doctoral graduates as the potential outcome of transitions within the national system: from PhD degree to professorship, possibly including some postdoc experience. The available data do not allow us to include those awarded their PhD degree from a foreign university or those in academic positions abroad; thus, we cannot assess what constitutes a “typical” academic career in Italy.Footnote 10

However, the budget cuts imposed in 2009 and the abolition in 2010 of open-ended contracts for assistant professors (law n.240/2010) significantly modified internal career paths. The open-ended contracts (ricercatore universitario a tempo indeterminato) were replaced by three-year fixed contracts (with the possibility of one renewal for an additional 2 years—ricercatore universitario a tempo determinato di tipo A) and three-year tenure-track contracts (ricercatore universitario a tempo determinato di tipo B), which could be converted into open-ended contracts for associate professors upon attainment of the national qualification (abilitazione scientifica nazionale). Both types of vacancies were allocated according to open competitions at the local level.Footnote 11 The selection procedure was also modified: before the reform, candidates were required to pass two written exams to prove their knowledge of the discipline; after the reform, these exams were abolished and candidate were assessed only on their CVs (although many departments required shortlisted candidates to give a seminar, resembling job market paper interviews in the US system). The sequential nature of this reform, which was aimed at accelerating career progress for the most brilliant candidates, ultimately increased the queue for entry to academia.Footnote 12 Our analysis highlights the consequences of these policy changes.

2.1 The PhD Database

The first archive contains information on PhD students and graduates. At the moment of latest data retrieval (6/5/2019), the archive contained 175,423 individuals. After some data cleaning to exclude inaccurate repeat records, interrupted careers, dual entries for individuals with more than one doctoral degree,Footnote 13 we were left with 172,552 records. Table 2 groups PhD students by cohort of entry, which corresponds to national admission waves (ciclo di dottorato). It can be seen that more than 10% of PhD students did not complete their study course or did not defend their thesis. Since we are interested in the potential advantage from obtaining an Italian PhD for the probability of an academic career in an Italian university, we restrict our analysis to the 107,801 individuals (bold figures in Table 2) who were enrolled in PhD study programmes between the 19th and the 29th cycles, corresponding to completion years between 2006 and 2018.Footnote 14

Table 3 shows the geographical distribution and research area of the PhD degrees. The share in the South declined by approximately 12 percentage points over a decade. In the case of discipline, the meanwhile stem (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) and life (biology, medicine, veterinary science) have expanded by 10 percentage points in both the North and the South, at the expenses of ssh (social science and humanities). Based on information on the labour market transitions of BA and MA graduates, stem and life PhDs confer a significant private sector employment advantages, which might account for the decline in transition to an academic career. Eventually, the gender partition fluctuates with a slight majority to the female component.

2.2 The Postdoc Database

The second archive includes postdoc positions (assegni di ricerca), which were introduced by the 1998 budget law.Footnote 15 The database is organized by events with 186,948 postdoc positions created between 1 September 1998 as starting date and expiration dates reaching 1 May 2022. These positions involved 80,659 scholars, which suggests that more than half obtained more than one position. In order to study the relative contribution of postdoc experience to the probability of an academic career, we retain only those positions that were still active or became active after 1 January 2006, when we start observing completed PhD degrees. Table 4 indicates that most postdoc positions (85%) were in Northern and Central universities, where their repeated use was also more frequent. The market seems segmented since the fraction of individuals who enjoyed a postdoc position in both macro-partitions is small.

The duration of most of these postdocs is one year or less (72% in stem, 71% in life and ssh). Less than 3% of postdoc positions are for more than two years (see Table 5).Footnote 16

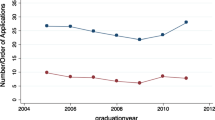

Figure 1 shows that the offer of postdoc positions is a relatively recent phenomenon in Italian academia: they became more frequent after open-ended contracts for assistant professors were abolished in 2010. First, the increase in the assistant professor turnover rate reduced the number of teaching and/or research assistant jobs previously filled by tenured assistant professors, thus creating a demand for collaborators in research and teaching. Second, exempting postdoc scholarships from tax created an incentive to create postdocs rather than other forms of contractual arrangements. Figure 1 shows that, overall, Italy has offered an average of 14,000 new postdoc openings every year since the reform (in line with the aggregate figures in Table 1).

2.3 The Academics Database

The third archive includes administrative data on professors employed in Italian universities between 2010 and 2020. Table 6 shows a significant decline of around 8 percentage points, driven mostly by assistant professors. If we consider open-ended and fixed-term assistant professor contracts, we observe an overall decline of 22% (with an internal reallocation towards the temporary component, currently at 38%), followed by a similar (though smaller) decline of 10% in full professors. Over the same period, we observe a large wave of promotions from open-ended assistant professor to associate professor based on funds aimed at reducing the number of assistant professor positions (described as ruolo ad esaurimento, depletable position).

If we consider the final year (see Table 7), we see a new hiring pattern related to the newly created assistant professor position associated with a fixed-term contract: two-thirds of these individuals were awarded their PhD degree by and/or worked as a postdoc in an Italian university.Footnote 17 Unfortunately we ignore the date of entries to academia before 2010. However, to partially account for this, the right-hand panel in Table 7 includes only academics aged less than 40 years, which corresponds to 10% of the relevant population. For almost all positions, the fraction of doctoral graduates whose degree was awarded by an Italian institution jumps to 81%, confirming that among the most recent cohorts a PhD degree is required to obtain a position in Italian academia. Should we obtain data on PhD degrees awarded by foreign universities, this share would likely be closer to 100%. This is not surprising since law 240/2010 made a PhD degree a necessary requirement for the position of assistant professor with a fixed-term contract, however, it became enforceable only after 2016.Footnote 18

For this reason we focus on new entrants (i.e. hired as assistant/associate/full professors) over the period 2010–19.Footnote 19 Thus, the temporal variations in the relevant share of Italian PhDs among newly hired professors (see Fig. 2) reflect both the limits of our administrative data and variations in the enforceability of the law. If we consider the most recent years as stable, we can argue that, currently, newly hired professors have a PhD degree, two-thirds from an Italian university and (quite likely) one-third from a foreign university. Also, in two-thirds of cases they have proof of research activity as postdocs. We also investigated whether there were variations in this dynamics by gender, but found no significant differences (see Table 8). However, we identified a clear declining trend in university hirings in the South, and a gradual substitutions of social science and humanities positions by life sciences.

3 The Transition to Academic Careers

By merging the three datasets, we obtain a population of 144,446 individuals who completed their PhD degrees in an Italian university between 2006 and 2018 and/or held a (concluded) postdoc position in an Italian university between 2006 and 2019. This population is observed entering Italian academia during the period 2010–2019, and 10,104 had been appointed professor by the end of the sample period (see Table 9).

We first examine the reduced academic opportunities for the most recent cohorts. Given the structure of the data, if individuals enter the sample in different years, but are observed in the same year, older candidates have more time to obtain an academic post. To enable comparability, Table 10 presents the data in a moving window, recording eventual appointments in the six years following award of the PhD degree and/or completion of a postdoc period (choosing the earlier date in the case of both conditions being present).

If we consider all candidates, the probability of appointment declines by 2 percent points over eight years, but this hides a compositional effect: at the start of the period, all candidates awarded a PhD degree were headed towards an academic position and a postdoc position was a threat to promotion. At the end of the period, individuals with a PhD degree and postdoc experience were five times more likely to achieve an academic position compared to individuals with only a PhD degree or a postdoc experience. The disadvantage for the candidate is clear: if we observe the mean waiting period between degree completion and academic appointment (within the 6-year window), we see that it is around two years for only PhD degree and around four years for PhD + Postdoc candidates. The changing composition of the pool of newly appointed professors seems to keep an almost constant age at first appointment: the increasing age for PhD-only candidates is mostly counterbalanced by the declining age for the PhD + Postdoc group. Thus, over the sample period the age of first appointment across a six-year window, increases by one year only.Footnote 20

The worsening conditions for the most recent cohorts who faced the hiring freeze and the reform of the assistant professorship after 2010, are confirmed by applying survival analysis for the risk of being appointed professor. The Kaplan–Meier failure functions (i.e. the share of promoted by year of entry in the sample) reported in Fig. 3 suggest that if we abstract from the small initial cohort (made up of late completers, thus not fully representative of the quality of the candidates), the cohorts completing their degree in the period 2007–2009 benefited from a higher chance of obtaining a position in Italian academia, compared to later cohorts. The convexity of the lines associated to these cohorts is consistent with the effect of reopening vacancies in recent years.

The compositional effects presented in Table 10 can be represented by a different disaggregation of Kaplan–Meier analysis. Figure 4 depicts the failure function by type of credentials: candidates with just one credential (either a PhD degree or a postdoc experience) are at a disadvantage with respect to candidates with both types of credentials.Footnote 21

We are interested, also, in potential heterogeneity in academic prospects. We have shown that there are differences associated to period of completion and the type of credentials obtained by candidates, but need to examine the effects of gender, location and discipline differences. Figure 5 plots failure functions by gender and provides clear evidence of gender discrimination against women. The horizontal distance between the two lines describes the slower queue for females: at five years after completion, a man has a 5.6 point probability of an academic appointment, whereas it takes 7.5 years for women. At 13 years after graduation or postdoc completion, a women has the same chance of obtaining an academic position that a man has after 8 years.

This may be related, in part, to disciplinary differences, since academic career progression is faster in the social sciences and stem disciplines and significantly shorter than in life science disciplines (graph not shown). At 5 years after completion, a social science scholar has a 5.2 points chance of promotion; for stem scholars reaching the same probability requires 5.3 years and for life sciences scholars it takes 7 years. Since women are underrepresented in stem and overrepresented in the other two disciplinary groups,Footnote 22 we can conclude that the disciplinary divide partly explains gender differences as shown in Fig. 6 which depicts both gender and discipline. Figure 6 shows that women in life sciences experience slower career progression, attributable mostly to the long medical study period where the need for both academic and hospital experience imposes a double penalty.

We explored another compositional effect related to the problem of “inbreeding” in Italian academia. In Italy, but not in other countries, universities are allowed to recruit their own PhD graduates: as a consequence candidates are more likely to be co-opted within the faculty if they are PhDs graduates from the same departments (as shown by Fig. 7, where local candidates almost double external ones in the appointment probability between year 3 and year 10 from degree defence).

A final and quite surprising result is the finding that there are no academic career differences between the North-Centre and the South of Italy (see Fig. 8). In Fig. 8, geographical location is the location of the university awarding the PhD degree and/or the location of the postdoc collaboration.Footnote 23 We observe a fraction of “movers”, but only among the most successful graduates: 14.9% of applicants educated in Southern universities were appointed to positions in Northern universities and 8.6% of PhDs and/or postdocs from Northern universities were hired by Southern universities. However, given the non-observability of intended moves, we cannot assess whether moving to a different macro-region increases the probability of appointment and/or speeds up the promotion process. The similar career patterns in both macro-regions and the observed decline in the number of PhD degrees awarded by Southern universities (Table 3) combined with the reduced number of vacancies posted by Southern universities (Table 8) and the reduced mobility noted above, suggest that the Italian academic market is significantly segmented and spill-overs across universities tend to be minimal (consistent with the dynamics in Fig. 7).

We employ a Cox proportional hazard modelling to career dynamics and heterogeneous effects to estimate the relative risk of being appointed professor associated to different covariates; the reference case is a male aged 24 with a social sciences PhD awarded by a Southern university in the initial year (2007). Table 11 presents the estimates for two complementary models in a multivariate context, to study the correlation of each variable keeping into account the effects of the others. The first model is a Cox proportional hazard model of the risk of entering academia and, to enable comparison, we report the coefficients rather than the hazards. The second model is a standard probit, where the positive outcome is being appointed to an academic position. Column 3 reports the marginal effects of the probit model, evaluated at the sample mean, to capture the size of the effect.

Both models show that women, young individuals and candidates born abroad are at disadvantaged in terms of entering an academic career. Working in a stem or social science field increases the likelihood of an academic career compared to working in life sciences. University geographical location in the country shows no differences.Footnote 24 Being an incumbent candidate increases the probability of appointment by 42.1 percentage points vis a vis an external candidate.

In terms of qualifications and experience, candidates with a PhD degree and a postdoc experience have a 7.2 percentage points higher probability of an academic hiring vis a vis candidates with a PhD degree. Postdoc experience without an Italian PhD is associated to a negative premium: this reflects the predominance of short-term collaborations, but no long-term academic aspiration (assegno di ricerca di tipo B). When we consider the cohort dummies, we find that the cohorts between 2010 and 2014 are disadvantaged by the hiring freeze. The time profiles based on the two models differ: the Cox model shows that the cohorts that completed their degrees/experience after 2010 retained their positive advantage with respect to the initial cohort, with the best candidates being hired soonest. The probit model suggests that these cohorts are indistinguishable in the probability of academic appointment with respect to the excluded case.

4 Concluding Remarks

This chapter provides new evidence regarding the initial steps towards an academic career in Italy. Contrary to the literature, which suggests that one in three individuals who complete their PhD degree programmes in an Italian university is appointed to the position of professor, we find that this probability has more than halved. Among those awarded their PhD degrees or completed postdoc experience in 2007, only 12.9% were in an academic position in 2019. This is due mostly to the temporary hiring freeze which affected the whole of Italy’s public administration in the period 2010–14. However, there is also evidence of increased competition from abroad, since half of newly hired candidates do not have an Italian PhD degree (and, therefore, were likely awarded one by a foreign university since a PhD degree is a precondition for applying for an assistant professor vacancy).

We found also that rather than a transition from PhD completion to academic position, the sequence has gradually become doctoral graduate, postdoc experience and then an academic position. This has increased the time from study completion to appointment. If we consider that the average duration of a postdoc position is 2.5 years in our dataset and it gives access at best to a two-year temporary assistant professor contract, we can expect the following sequence. Based on the averages for the individuals in our sample, PhD defence occurs at 32.7 years of age, followed by a transition period of 4 years (including a 2.5 year postdoc position) and for one in ten candidates, at 36.7 years of age, a temporary three-year contract (ricercatore a tempo determinato di tipo A). This equates reaching almost the age of 40 years of age without a permanent position. For the best researchers who have obtained the appropriate qualification (abilitazione scientifica nazionale), application for a tenure track position is possible and, after three years, at around age 43, an associate professor position. Since in 2010, the average age of an assistant professor on an open end contract was 34 years (44 years for associate professor) we can see how much more difficult it has become to obtain a permanent position in academia in Italy.

We found heterogeneity in transition probabilities. Women, young individuals and foreign-born candidates are negatively discriminated, regardless of research field. Internal candidates receive an undue advantage. This should concern policy-makers, since there are no reasons for these selection biases. In the case of gender, it could be argued that the length of transition impinges on and causes conflicts between childbearing and academic aspirations.Footnote 25 Unfortunately, we have no information on the scientific productivity of these candidates since most have few entries in the Web of Science and Scopus databases. If we could identify a proxy for their academic impact, we could investigate whether this negative discrimination is based on productivity or is purely statistical discrimination.

We found an absence of geographical differences in the transition probability, which contradicts claims that Southern universities suffered more than Northern universities from the cuts imposed during the period of financial austerity. However, we found that their share of PhD degrees and vacancies/promotions declined in the period analysed, suggesting the presence of a consistent brain drain. Finally, we found that research field matters: careers in social sciences and stem progress more rapidly than those in life science.

Our study has two main limitations, which suggest caution when interpreting our results. The first limitation is that we do not observe the alternative careers of candidates who emigrate, have experience at a foreign university, and then return to Italy to take up an academic position. Anecdotal evidence suggests that their share is increasing since Italian doctoral graduates are found in postdoc positions in many departments of foreign universities. It would be useful to gather data on this (temporary?) brain drain. The only current source of administrative information on this aspect is AIRE (the registry of Italians residing abroad), but this would underestimate their number. Data could be obtained by parsing the curricula of the applicants to the competition for assistant professorships, but this would be rather time consuming since the information is not organized in a consistent way.

The second limitation is related to outside options for the doctoral graduates. Nine out of ten abandon any academic aspirations and apply for positions in the public administration or the private sector. We do not have information on the monetary return associated with a PhD degree, but it is likely that the quality of the job obtained compensates for the lack of monetary incentives. Otherwise, it would be puzzling that more than 10,000 Italian graduates embark on a PhD degree with no expectation of future outcomes.

Evidence of a brain drain to foreign universities and companies can be seen as confirming the quality of the training offered by Italian universities. Being a net exporter of PhD graduates is the joint outcome of excess supply (recall the doubling of PhD positions over the last decades) and lack of demand (the number of posts in academia has reduced over the same time period), combined with a low price (represented by the options outside of academia). In the absence of indirect proxies for candidate abilities (such as scientific productivity), we are unable to assess whether self-sorting of candidates deprives the country of the brightest individuals.

Notes

- 1.

“With the exceptions of salaries and the teaching load, Italy shows elements of job attractiveness below average, in particular, the quality of peers, funding and career perspectives as well as the quality of life” (Janger et al., 2013, p. 17).

- 2.

However, the corresponding figures for Italy at entry level seem underestimated: the European Commission (2007, Table 12) reports 12.648 euro for a researcher with 0–4 years of experience, against an EU-25 average of 20.374 euro. However, the European University Institute Academic Career Observatory in Florence (https://www.eui.eu/en/academic-units/max-weber-programme-for-postdoctoral-studies/aco-academic-careers-observatory) reports an monthly entry salary for assistant professors in 2007 of 1500 euro (gross of tax, not corrected for PPP) against a corresponding value of 3708 euros in the USA and 3810 euros in the UK.

- 3.

“A drastic divide emerges between researchers in Italy and abroad with regards to the mechanisms of hiring and in terms of remuneration and career prospects. Recruitment in the home institution is considered to be transparent and merit-based by 57% of researchers in Italy and 80% of those abroad. PhDs and younger researchers in Italy have the most critical view of recruitment mechanisms in place. Considering the criteria for career progression, the same gap emerges. Merit is considered as the operating criteria by 54% of researchers in Italy against 75% of those abroad. Tenured positions are considered to be assigned on the basis of merit by 43% of researchers in Italy and by 62% of those abroad … The examination of remuneration shows that the share of researchers reporting to be badly paid or paid just to make ends meet is 47% in Italy and 15% for Italians abroad”. (Nascia et al., 2021, p. 6).

- 4.

All these comparisons are potentially biased by self-selection: the best Italian PhDs could migrate abroad where they achieve faster career progression, simply because they are more productive. This is confirmed by Coda and Geuna (2018), who provide evidence that internationally mobile doctoral graduates perform better and have stronger international networks than their domestic peers.

- 5.

- 6.

“In a nutshell, in the second half of the 2000s, a set of academic reforms (1) cut the funding for the recruitment of new researchers (assistant professors) and for the promotion of academics (Berlusconi reforms—the so-called turnover block [2008]) and (2) abolished open-ended contracts at the start of the academic career (assistant professor) in favour of fixed term contracts, mostly without a tenure track, and put constraints on the renewals of temporary contracts in academia (Gelmini reform [2010])” (Passaretta et al., 2019, p. 545).

- 7.

- 8.

See Table 12 in Coda and Geuna (2020).

- 9.

Our dataset contains more holders than Coda and Geuna (2020). Looking at their Table 1, for the period 2003–2006, they, respectively, count 6680, 8287, 9344 and 6795 PhDs. In our database for the same years, we count 10,665, 11,093, 11,291 and 11,395, suggesting that the parsing from the national library may be defective (for example, PhD schools—istituti a statuto speciale, like the Scuola Normale in Pisa—are excluded) or that a portion of PhDs did not comply with the legal obligation.

- 10.

The MIUR data do not contain information on PhD degrees awarded by foreign universities. If we observe a candidate in an assistant professor position who does not have a PhD degree awarded by an Italian university after 2010, we can assume that the individual was awarded the PhD degree from a foreign university. We still ignore the number of potential applicants and the proportion of candidates with two PhD degrees. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many doctoral students in Italian universities use their study abroad period to enrol in a foreign PhD programme (and obtained a second PhD degree after completing their studies in Italy).

- 11.

The second type was open only to candidates who had already obtained the first type of contract or who had held a postdoc position for at least 3 years. To try to limit fixed-term employment, the law introduced a cap of five years on the cumulative duration of postdocs and fixed-term contracts for assistant professorships. Note that, for the first time, completion of a PhD degree became a prerequisite for application to assistant professor.

- 12.

This is openly recognized in official accounts as systemic failure: “La ratio della riforma attuata dalla legge n. 240/2010 si basava sull’idea che la sostituzione delle figure a tempo indeterminato con quelle a tempo determinato avrebbe dovuto aumentare competitività e selezione basata sul merito, portando i ricercatori più meritevoli a transitare in poco tempo nel ruolo degli associati (tenure track). Tuttavia, il percorso per approdare a professore associato è costellato da una serie di posizioni a tempo determinato, partendo dall’assegno di ricerca (che deve essere preceduto da tre anni di dottorato), per una durata massima pari a quattro anni, cui segue un concorso per ricercatore a tempo determinato di tipo A (la cui durata massima è di cinque anni), per poi giungere al posto di ricercatore di tipo B, della durata di un triennio e suscettibile di conversione in professore associato, nel caso in cui sia stata conseguita l’Abilitazione Scientifica Nazionale” (Corte dei Conti, 2021, p. 135).

- 13.

2490 individuals have two PhD degrees and 75 have more than two PhD degrees. To preserve sample size, we consider the oldest degree.

- 14.

- 15.

See item 6 art.51 in law no.447/1997, which sets a maximum of 8 years (reduced to 4 for PhDs students who benefit from a scholarship). Art.22 of law no. 240/2010 revised the maximum length to 4 years, making postdoc scholarships exempt from tax but liable for social contributions to pension schemes.

- 16.

While we have no information on the type of collaboration, recall that there are two types of postdoc position: assegno di tipo A, typically lasting 2 years, renewable for an additional 2 years, assigned based on open competitions, CVs and individual research projects; and assegno di tipo B, short-term collaborations for specific projects, often lasting only 6 months, based on discretionary hiring of principal investigators of larger research projects. Table 5 shows that this second type was frequent in stem schools and does not necessarily reflect any academic aspirations, but rather temporary job opportunities for new graduates.

- 17.

There is a caveat: we do not have information on Italian PhD degrees obtained before 2006, so it is likely that the shares indicated for full and associate professors constitute lower bound estimates of the actual shares.

- 18.

Item 2b art.24 of law 240/2010 sets out the admission requirements for applying for a fixed-term assistant professor position: “b) ammissione alle procedure dei possessori del titolo di dottore di ricerca o titolo equivalente, ovvero, per i settori interessati, del diploma di specializzazione medica, nonchè di eventuali ulteriori requisiti definiti nel regolamento di ateneo, con esclusione dei soggetti già assunti a tempo indeterminato come professori universitari di prima o di seconda fascia o come ricercatori, ancorchè cessati dal servizio”. The same law (para 13 of art.29) allows 5 years of derogation of this requirement: “13. Fino all’anno 2015 la laurea magistrale o equivalente, unitamente ad un curriculum scientifico professionale idoneo allo svolgimento di attività di ricerca, è titolo valido per la partecipazione alle procedure pubbliche di selezione relative ai contratti di cui all’articolo 24”.

- 19.

Since our academics data start in 2010, we can reconstruct new entries based on differences between 2011 and 2010 (and so on). For the earlier years (say, an assistant professor hired in 2009) we proxy new entries by restricting them to teaching staff existing in 2010 younger than 41, who were most likely hired in the previous decade.

- 20.

Conditions worsen over time, such that candidates completing their degrees and/or postdoc experience in 2006 could be observed until 2019: if we take the average age among all appointees by year of appointment, we observe 34.7 years of age in 2010 increasing to 38.9 years in 2019.

- 21.

Candidates with just postdoc experience could conceal scholars who were awarded their PhD degree by a foreign university and are trying to (re)enter the domestic academic market. However, the flat line in Fig. 4 is not in line with this interpretation, suggesting that candidates with a foreign PhD are also more likely to get postdoc experience abroad and to use this experience to apply for a higher academic position (such as associate professors) in Italy. Table 8 shows that half of new appointees have neither a PhD degree from nor postdoc experience in an Italian university. This can be taken as indirect evidence of the brain drain that has afflicted the Italian highly skilled scholars market.

- 22.

In the present working sample (based on disciplinary allocation of PhDs’ programs and/or postdoc disciplinary requirements), where the gender distribution is 48.8% of men and 51.2% of women, the male distribution is 46.1% in stem, 23.8% in life and 30.6% in ssh, while the corresponding figures for females are 22.8%, 39.9% and 37.3%.

- 23.

Some candidates occupied postdoc positions in both regions: in these cases, location is attributed according to the prevailing length of the postdoc collaboration.

- 24.

This is confirmed if we split the sample into discipline subgroups and re-estimate the model based on subsamples. The estimated marginal impact of being a woman is −0.015 for stem and social sciences and −0.025 for life sciences.

- 25.

See chapter “Academic Careers and Fertility Decisions” in this volume.

References

Ballarino, G. (2020). Come cambia il dottorato di ricerca. Organizzazione istituzionale e sbocchi occupazionali in comparazione internazionale. Rapporto di ricerca per UNIRES.

Coda Zabetta, M., & Geuna, A. (2018). International postdoctoral mobility and career path: Evidence from Italian academia. Mimeo.

Coda Zabetta, M., & Geuna, A. (2020). Italian Doctorate holders and academic career. progression in the period 1986–2015. Carlo Alberto Notebooks n. 629.

Corte dei Conti. (2021). Referto sul Sistema Universitario, Rome.

De Angelis, G., & Grüning, B. (2020). Gender inequality in precarious academic work: Female adjunct professors in Italy. Frontiers in Sociology., 4, 87. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00087

Decataldo, A., Giancola, O., & Trivellato, P. (2016). L’occupazione dei PhD in ambito accademico e nel mercato esterno. La mobilità geografica come vincolo ed opportunità. Comunicazione convegno AIS-Verona, mimeo.

DeLillo, A., & Schizzerotto, A. (1985). La valutazione sociale delle occupazioni. il Mulino.

European Commission. (2007). Remuneration of researchers in the public and private sectors. Carsa.

Giglioli, P. P. (1982). Baroni e burocrati. Il ceto accademico italiano. il Mulino.

Istat. (2010). L’inserimento professionale dei dottori di ricerca. Anno 2009–2010, Statistiche in breve. 14/12/2010.

Istat. (2015). L’inserimento professionale dei dottori di ricerca - Anno 2014, Statistiche Report, 21/1/2015.

Istat. (2018). L’inserimento professionale dei dottori di ricerca – Anno 2018. Statistiche Report 26/11/2018.

Janger, J., Strauss, A., & Campbell, D. F. J. (2013). Academic careers: a cross-country perspective. WWW for Europe Working Paper no 37.

Marini, G., Locke, W., & Whitchurch, C. (2019, March). The future higher education workforce in locally and globally engaged higher education institutions: A review of the literature on the topic of “the academic workforce”. Centre for global higher education working paper n. 43.

Meraviglia, C., & Accornero, L. (2007). La valutazione sociale delle occupazioni nell’Italia contemporanea: una nuova scala per vecchie ipotesi. Quaderni di Sociologia, 45, 19–73.

Moscati, R. (2020). Academics facing unpredictable changes. Scuola Democratica, 3, 405–416.

Nascia, L., Pianta, M., & Zacharewicz, T. (2021). Staying or leaving? Patterns and determinants of Italian researchers’ migration. Science and Public Policy, 2021, 1–12.

Passaretta, G., Trivellato, P., & Triventi, M. (2019). Between academia and labour market. The occupational outcomes of PhD graduates in a period of academic reforms and economic crisis. Higher Education, 77, 541–559.

Perotti, R. (2008). L’università truccata. Einaudi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Checchi, D., Cicero, T. (2022). Is Entering Italian Academia Getting Harder?. In: Checchi, D., Jappelli, T., Uricchio, A. (eds) Teaching, Research and Academic Careers. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07438-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07438-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-07437-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-07438-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)