Abstract

The biodiversity of the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea is valued internationally for its uniqueness and locally for its contribution to human welfare, but it is under growing anthropogenic pressure. We provide an overview of recent progress, ongoing challenges, and future directions for terrestrial and marine conservation. The islands were colonized in the late fifteenth century and have since relied heavily on international markets. Nevertheless, the livelihoods of many islanders depend directly on local natural resources, and growing human populations and economies are intensifying the use of these resources, including timber, land, and fisheries. Here we summarize conservation initiatives on the islands, including pivotal projects and achievements, as well as the rise of civil society and governmental engagement. We also review species and site-based conservation priorities and highlight the need for continuous updating based on ongoing research. Engagement in conservation has increased steadily in recent decades but not fast enough to counteract the growth of anthropogenic pressure on biodiversity. Fostering capacity building, environmental awareness, and research is thus urgent to ensure a thriving future for the islands, able to reconcile economic development and biodiversity conservation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea (Príncipe, São Tomé, and Annobón) are widely recognized as global priorities for biodiversity conservation. Considering their small size, they have exceptionally high numbers of endemic and threatened species (Jones 1994). They are part of the “Guinean Forests of West Africa” biodiversity hotspot (Myers et al. 2000) and of the “Cameroon-Guinea” Centre of Plant Diversity (WWF and IUCN 1994). These islands also retain a high proportion of natural vegetation cover (WWF 2019) compared to other oceanic islands (e.g., Norder et al. 2020), having relatively large extents of well-preserved native vegetation across lowland, montane, and mist forests (Exell 1944). Among the islands, mist forests are exclusive to São Tomé and hold especially high numbers of endemic and threatened plant species (Dauby et al. 2022; Stévart et al. 2022). Being mountainous, the islands function as ecological and evolutionary refugia, offering a wide variety of stable environments whose climates are buffered by the ocean (Ceríaco et al. 2022a). Príncipe and São Tomé also have a few mangrove areas, which despite their small size provide important ecosystem services (Afonso et al. 2021; Cravo 2021). The islands are situated within one of the 18 global hotspots for marine conservation (Roberts et al. 2002) and the most important marine biodiversity hotspot of the “West African Coast” (Polidoro et al. 2017), which connects the eastern and western Atlantic marine faunas (Wirtz et al. 2007). Their marine environments include areas that are key for the life cycles of seabirds, marine megafauna (cetaceans, sea turtles, rays, and sharks), and large, commercially valuable, pelagic, migratory fish species.

Here, we provide an overview of terrestrial and marine conservation in the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea. We start by describing the links between biodiversity and livelihoods on the islands, focusing on the direct dependence of people on natural resources, and on their unsustainable use, to understand current threats to biodiversity. Then, we provide a brief history of conservation initiatives on the islands, summarizing the history of conservation movements and providing an overview of species conservation statuses and of sites prioritized for conservation. Finally, we highlight important lessons and ongoing challenges to define priorities for the future of conservation on these unique islands.

People and Biodiversity: Close Together on Small Islands

The oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea are thought to have been uninhabited until Portuguese sailors reached São Tomé on 21 December 1471, Príncipe on 17 January 1472, and Annobón on 1 January 1473 (Seibert 2016). European colonization of the islands started during the fifteenth century and focused on the slave trade and on exploiting cash crops, such as sugar cane, coffee, and cocoa (Eyzaguirre 1986). The peoples of the islands thus derive mostly from a mixture of African and European settlers (Hagemeijer and Rocha 2019; Almeida et al. 2021). The relatively recent colonization and economic reliance on intensive agriculture are reflected in the somewhat superficial connection to local nature when compared to other African cultures, and instead bear stronger similarity with other colonial-based cultures, such as those of many Caribbean islands (Eyzaguirre 1986). A connection with nature is nevertheless embedded in the traditions of islanders, namely in the cuisine (Gonçalves et al. 2014), medicine (Roseira 1984; Madureira et al. 2008), beliefs, and worldviews (Valverde 2000).

The human population is unevenly split between islands: Príncipe is 139 km2 and has 8778 inhabitants (65/km2), São Tomé is 857 km2 and has 201,462 inhabitants (235/km2—INESTP 2019), and Annobón is 17 km2 and has 5314 inhabitants (313/km2—INEGE 2018). The rugged terrain of the islands has meant that, up until today, most people live by the coast (Norder et al. 2020), benefiting from resources provided by both the ocean and the forest (e.g., Torres 2005; Pereira 2021). In addition, human activities are concentrated in the drier and flatter coasts in the north of the islands, whereas the mountainous south and center are still dominated by rainforest (Jones and Tye 2006). These contrasting landscapes provide ecosystem services that are key for human wellbeing in the islands, and that islanders recognize as essential: forests are important for pure air, water, foraged foods, medicinal plants, and tourism, while plantations are key for agriculture, livestock, and fruits (BirdLife International 2021a).

The economy of Annobón is mostly focused on services and relies on national income resulting from oil revenues (INEGE 2018), while that of Príncipe and São Tomé is heavily dependent on foreign aid and on export crops (INESTP 2019). All islands are heavily reliant on imports, even though internal markets and the subsistence of most islanders are strongly based on agriculture and other activities on the primary sector. Fisheries (Dias 2013), fuelwood and charcoal (Nuno 2021), and timber (do Espírito et al. 2020) are essential to meet basic needs, and thus natural resources are viewed as a primary source of protein, energy, and shelter that also create diverse job opportunities. Some natural resources might play a small role in subsistence overall, such as hunting (Carvalho et al. 2015a) and medicinal plants (Madureira et al. 2008), but their significance should not be overlooked, even if it is predominantly cultural. Economic and cultural importance ascribed to introduced species, some of which are invasive, also has relevant implications for conservation. For instance, the West African giant land snail, Archachatina marginata (Swainson, 1821), is an important source of protein and income, particularly among vulnerable social groups (Pereira 2021). More broadly, there is also a greater awareness of the economic benefits and uses of introduced species than of the endemic-rich native biodiversity, which might hinder willingness to adopt conservation measures (Carvalho et al. 2015b; Panisi et al. 2022).

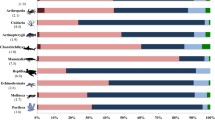

Having an economy largely based on cash crops has been, and still is, the defining factor for the extent and severity of anthropogenic impacts on the environment. Historically, deforestation and other key components of human impacts on the islands have been decoupled from population size (Norder et al. 2020). This is because human populations on the islands are heavily reliant on external markets, producing agricultural goods to export and then importing much of what is consumed on the islands (Eyzaguirre 1986). Nevertheless, both the economy and the human population have been rapidly growing in recent times. These increases are most notable in São Tomé, which has rapidly been growing since the 2000s (Muñoz-Torrent et al. 2022) when malaria infections were greatly reduced (Lee et al. 2010). The impacts of this growth are noticeable in the depletion of many natural resources (Fig. 24.1), including timber (do Espírito et al. 2020), land conversion to agriculture (de Lima 2012; Soares 2017), quarry species (Carvalho 2015), and fisheries (Belhabib 2015; Maia et al. 2018; Nuno et al. 2021). The underlying effects of less direct anthropogenic impacts, such as introduced species and climate change remain largely unstudied (but see Brito 2013; Heleno et al. 2022).

Examples of threats to the endemic-rich biodiversity of the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea: (1) Fire and agriculture shape the landscape in the driest portions of northern São Tomé; (2, 3) Small plots of horticulture around Bom Sucesso threaten the endemic-rich montane forests of São Tomé, encroaching on São Tomé Obô Natural Park; (4) Illegal selective logging is widespread on São Tomé; (5) Several introduced species, such as the Mona Monkey Cercopithecus mona (Schreber, 1774) threaten ecosystem function; (6) Charcoal production is widespread but particularly intensive in the drier north of São Tomé; (7) Hunting threatens several endemic birds, such as the Endangered Sao Tome green-pigeon Treron sanctithomae (Gmelin, 1789); (8) Longline fishing (baited hooks linked to short lines attached to a long main line) is a damaging practice that destroys the ocean floor and results in bycatch and discarded fishing gear. Photo credits: (1–3, 6) Jean-Baptiste Deffontaines, (4, 5) Ricardo F. de Lima, (7) Ricardo Rocha, (8) Luísa Madruga

Major threats to the conservation of terrestrial biodiversity identified by local stakeholders include tree logging, land-use changes derived mostly from agricultural pressure, hunting and collection of threatened and endemic species, invasive introduced species, and the development of macroprojects (BirdLife International 2019). These threats strongly coincide with those that had already been identified for the islands (Jones et al. 1991; Oyono et al. 2014; Ndang’ang’a et al. 2014a, b), and largely match the most salient factors threatening species globally: habitat loss and degradation; overexploitation; invasive species; pollution, and global climate change (Vié et al. 2009).

Less is known about threats in marine environments. The overexploitation of fisheries is certainly relevant: the Marine Trophic Index in São Tomé and Príncipe scored 14.5 in a 0–100 range (Wendling et al. 2020), indicating that species higher in the food web might have been fished out and that fishing is now targeting lower trophic levels. Fisheries in São Tomé and Príncipe consist of small-scale activities focused on the territorial sea, and of European-dominated industrial fleets that extract most of the volume of fish removed from the Exclusive Economic Zone (Porriños 2021). The evaluation of fish stocks and the control of fishing have been almost inexistent, even though fishing agreements with the European Union represent 40% of the non-fiscal revenues of the country and are meant to promote sustainable fishing (FAO 2019). Increased pressure on marine resources is leading to the use of destructive practices that maximize catch in the short-term, but that threaten biodiversity, the livelihoods of coastal communities, and food security on the islands in the long term. The exploration of mineral resources in the oceans is increasingly a threat since large deposits of petroleum were found offshore in the 1990s. These are yet to be extracted but are already boosting the economy of the island (Frynas et al. 2003). Finally, there is also evidence that the waters around Annobón have been used to dump large quantities of toxic waste and that these activities have affected its marine life (Wood 2004).

Conservation Initiatives

Early in the twentieth century, several authors expressed concerns about the environmental implications of deforestation linked to the expansion of cocoa plantations on the islands, mentioning several actions to ensure the future of remaining forests, such as the protection of mountaintops (e.g., Campos 1908; Henriques 1917). These might be the first conservation safeguards known to take place on the islands. However, the collapse of the economy based on export crops (Eyzaguirre 1986), the focus of colonial scientific research on agricultural production, the poor local capacity and, later on, political instability linked to the post-independence period (Cruz 2014) meant that, for many decades biodiversity research was fairly limited (Ceríaco et al. 2022b). Only in the late 1980s, the first initiatives based on modern principles of conservation (Soulé 1985) started taking shape, following a few successful expeditions to the islands (Jones and Tye 1988; Jones et al. 1991; Atkinson et al. 1991).

In 1993, a workshop took place in Jersey (United Kingdom), bringing together several scientists to assess knowledge on the biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea islands (including Bioko) and define priorities for future research and conservation action (Juste and Fa 1994). The Gulf of Guinea Conservation Group emerged from this meeting and was the umbrella under which many scientists visited the islands over the next two decades, in great part thanks to the efforts of Angus Gascoigne, who resided in São Tomé and facilitated links to local institutions (Melo 2012).

Also, in 1993, the European Commission started funding the ECOFAC program, aiming to promote the conservation and sustainable use of forest ecosystems in central Africa (Table 24.1). Besides promoting numerous studies, ECOFAC was fundamental to many of the conservation efforts that have since taken place in São Tomé and Príncipe (Fig. 24.2), such as the establishment of terrestrial protected areas and other environmental legislation, the creation of the Bom Sucesso Botanical Garden and São Tomé and Príncipe National Herbarium (STPH; NYBG 2021), and the training of many islanders and foreigners that still work toward conservation on the islands. The Global Environment Facility has been another key source of funding for conservation on the islands over the last two decades (Table 24.1). More recently, other sources of funding, such as the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF 2021) or the Rufford Small Grants for Nature Conservation (The Rufford Foundation 2021) have allowed smaller projects to develop important complementary tools for conservation. Previous phases of ECOFAC have also covered Equatorial Guinea, where it coincided with the EU-funded project of Conservation and Rational Use of Forest Ecosystems (Conservación y Utilización Racional de los Ecosistemas Forestales—CUREF 1996–2001), aiming to describe ecosystems, to promote sustainable use of natural resources, and to create a network of protected areas (García and Eneme 1997, Angela Formia pers. comm.). However, it is unclear how these have contributed to creating the Annobón Nature Reserve or any other conservation initiative on the island.

Examples of conservation initiatives that have been taking place in the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea: (1) Sign marking the boundary of the São Tomé Obô Natural Park; (2) Small trees being distributed in a school in the buffer zone of the São Tomé Obô Natural Park; (3) An Obô guardian surveying the forests of São Tomé; (4) The orchidarium at the Bom Sucesso Botanical Garden in São Tomé; (5) Sea turtle hatcheries are used to protect nests at risk from feral animal predation, poaching and beach erosion in São Tomé and Príncipe; (6) Inspection of illegal logging activities in a forest in Príncipe; (7) Freshwater macroinvertebrates surveys in Rio Papagaio, Príncipe; (8) Young parabotanist surveying tree diversity in Príncipe. Photo credits: (1) Ricardo F. de Lima, (2) Raphaela Nazaré, (3, 4, 6) Jean-Baptiste Deffontaines, (5) Maria Branco, (7, 8) Vasco Pissarra | Fundação Príncipe

Since 2016, there has been a noticeable and much needed increased investment in coastal and marine conservation, focusing on sustainable fisheries through engagement with coastal fishing communities (Table 24.1), namely through the Omali vida nón project in Príncipe (Nuno 2019; FFI et al. 2021; Fundação Príncipe 2021d), and the Kike da mungu project in São Tomé (Oikos and MARAPA 2021). Building on these, since late 2018, Fauna & Flora International, in close collaboration with the government authorities, has partnered with Fundação Príncipe, Oikos, and MARAPA to establish a network of co-managed marine protected areas across São Tomé and Príncipe (BAF 2018). There have been significant efforts for the conservation of sea turtles on both of these islands (Associação Programa Tatô 2021; Fundação Príncipe 2021a; Ferreira-Airaud et al. 2022). There has also been some research on cetaceans in São Tomé (MARAPA 2021b), and in June 2021 a project has been approved to study the little known but highly threatened shark populations of São Tomé and Príncipe (NGANDU 2021).

Parallel to increased funding, civil society awareness toward conservation has also greatly increased over the past few decades, which is clearly reflected in the number and impact of local environmental non-governmental organizations (Ayres et al. 2022). MARAPA has been active in marine conservation initiatives for São Tomé Island, promoting sustainable fisheries and environmental education since its creation in 1999 (MARAPA 2021a). Associação Monte Pico emerged in 2006 from a group of Santomeans trained by ECOFAC; it has been working for sustainable ecotourism and rurality, and supporting scientific research and the management of protected areas (Associação Monte Pico 2021). Founded in 2015, Fundação Príncipe focuses on marine and terrestrial biodiversity conservation and the socio-economic development of Príncipe Island, in close partnership with regional authorities and communities (Fundação Príncipe 2021b). Since 2017, Rede.Bio has brought together seven environmental NGOs from São Tomé and Príncipe to promote integrated and sustainable development based on the protection and valorization of the natural heritage of the country, namely by reinforcing the participation of civil society in environmental governance (Rede.Bio 2021). Most recently, on October 16, 2020, the Gulf of Guinea Biodiversity Center had its inaugural meeting, bringing together national and international scientists and conservationists in an initiative that aims to facilitate research, education, and conservation of the unique diversity of the plants and animals of the islands (GGBC 2021).

Several international environmental organizations have also increased their presence in São Tomé and Príncipe. BirdLife International has had a long-term interest in these islands and has been increasing its presence especially since 2012, working with park authorities and other governmental institutions, and with communities to promote research, conservation, and empowerment. In 2018, BirdLife opened an office in country (BirdLife International 2021d). Fauna & Flora International has been working closely with Fundação Príncipe since its inception in 2015, to build conservation capacity, conduct research, raise environmental awareness, and diversify the livelihoods of communities on Príncipe (FFI 2021). Oikos—Cooperação e Desenvolvimento has had a growing presence in São Tomé and Príncipe since 2015, working toward the rational use of natural resources and enhanced livelihood in communities (Oikos 2021). In 2018, the international NGO Associação Programa Tatô was created to continue the work on marine conservation focusing on sea turtles that had been initiated by ECOFAC and MARAPA on São Tomé (Associação Programa Tatô 2021).

Little is known about conservation initiatives on Annobón, besides a few small conservation projects led by the national NGO Amigos de Natureleza y Desarollo de Guinea Ecuatorial (ANDEGE).

Over the last few decades, the São Tomé and Príncipe and Equatorial Guinea governments have also shown a strong national and international commitment to developing policies aiming to ensure the conservation of biodiversity (Appendix). In São Tomé and Príncipe, environmental responsibilities are split between the General Directorate for the Environment (part of the Ministry of Infrastructures, Natural Resources and Environment), the Fisheries Directorate, and the Forest and Biodiversity Directorate (both part of the Ministry for Agriculture, Fisheries and Rural Development). Príncipe is an autonomous region that has its own Regional Government, where environmental responsibilities are also split but following a distinct organization. This complex administrative structure, which often changes when a new government takes power, hinders progress and post-project sustainability of conservation initiatives. In Equatorial Guinea, the National Institute for Forestry Development and Protected Areas Management (INDEFOR-AP) from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests has developed a national network of protected areas and is responsible for environmental and wildlife conservation but little is known about the local government structure in the province of Annobón.

Threatened Species

The oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea hold several hundred endemic species, a number that will certainly increase as new endemics are still being described every year, even among the best-known taxonomic groups (de Lima 2016). Many of the endemic species are at risk of extinction and only terrestrial vertebrate species have been thoroughly evaluated (IUCN 2021). Out of 67 endemic species of terrestrial vertebrates, 58 have been assessed, and 18 are threatened. These include 11 birds (Melo et al. 2022), three mammals (Rainho et al. 2022), one reptile (Ceríaco et al. 2022c), and three amphibians (Bell et al. 2022). Of these species, four are Critically Endangered, ten are Endangered, and four are Vulnerable. Among terrestrial vertebrates, there are also seven Data Deficient, seven Near Threatened, and nine species that are not recognized or have not been assessed. Finally, both Príncipe and São Tomé have populations of the non-endemic Endangered Gray Parrot Erithacus psittacus Linnaeus, 1758.

Scientific research in coastal and marine environments is still scarce and mostly dedicated to studies of ichthyofauna. Fishes are the only non-terrestrial vertebrate group with endemic species (but see Flood et al. 2019). Out of 15 endemic species (Costa et al. 2022), only eight have been assessed (IUCN 2021): three Vulnerable and five Data Deficient. There are also large numbers of non-endemic fish species that are threatened including 6 Critically Endangered (all cartilaginous fishes), 15 Endangered (only two bony fishes), and 28 Vulnerable species (of which 16 are bony fishes). Additionally, 58 species are Data Deficient (all bony fishes) and nine are Near Threatened (including three cartilaginous fishes). The remaining threatened marine vertebrates are the Critically Endangered Hawksbill Turtle Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaeus, 1766), the Endangered Green Turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus, 1758), the Vulnerable Sperm Whale Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758, and three Vulnerable sea turtle species (Ferreira-Airaud et al. 2022). Additionally, there are also the Data Deficient Killer Whale Orcinus orca (Linnaeus, 1758), the Near Threatened False Killer Whale Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1846), and ten Least Concern cetacean species (Carvalho et al. 2022).

Very few endemic terrestrial invertebrates have been assessed by the IUCN: four mollusks, two crabs, one butterfly, and one dragonfly species, of which half are Data Deficient, two Near Threatened, one Least Concern, and only the Vulnerable Búzio-d’Obô Archachatina bicarinata (Bruguiere, 1792) is classified as threatened. Among the endemic marine invertebrates, only 23 species of mollusks have been assessed, all of which are Data Deficient, apart from the Vulnerable Haliotis geigeri Owen, 2014.

Among plants, 272 species have been assessed (IUCN 2021) out of a total that should exceed 1700 species (Garcia et al. 2022; Stévart et al. 2022). Out of almost 200 endemic plant species, only 49 have been assessed. These include two Extinct, two Critically Endangered, 14 Endangered, 22 Vulnerable, and 7 Near Threatened. Additionally, there are seven Endangered, 11 Vulnerable, 6 Near Threatened, and 1 Data Deficient plant species that are not endemic. Considering ongoing work, especially focusing on describing and red-listing seed plant species (Fundação Príncipe et al. 2021), it is evident that these numbers will greatly increase soon (Stévart et al. 2022). The situation is even more dire when it comes to fungi, a group for which Red List evaluations are scarce, with none of the species of the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea assessed so far (Desjardin and Perry 2022).

In 2004, amphibians, mammals, and birds were fully assessed for the first time (IUCN 2021). At that point, there were 38 recognized endemic species in these taxonomic groups, of which there were 14 threatened species (five Critically Endangered, three Endangered, and six Vulnerable), compared to the current 17 threatened species (four Critically Endangered, nine Endangered, and four Vulnerable) out of 45 recognized endemics. These trends reflect mostly an improvement of knowledge, showing that even among some of the best-studied groups there have been major changes not only in the Red List status but also in taxonomy. The high numbers of species that are still being described, that have not yet been assessed, or that remain Data Deficient attest to the urgent need for future work in the region. There has been an attempt to list species at the national level in São Tomé and Príncipe (Gascoigne 1995), but in recent years all assessments have been directly linked to the IUCN Red List because most species of interest are endemic, and therefore national assessments are also global.

In addition to the IUCN Red List, there are other tools to define priorities for species conservation. The EDGE of Existence is an example that combines the IUCN Red List status with the amount of unique evolutionary history represented by species of terrestrial vertebrates, cartilaginous fishes, and corals (EDGE 2021). This program has identified 31 species on the islands, including 16 cartilaginous fishes, one amphibian, three sea turtles, one cetacean, and ten birds as high priority. The Critically Endangered Dwarf Olive Ibis Bostrychia bocagei (Chapin, 1923), and the Endangered Newton’s Grassland Frog Ptychadena newtoni (Bocage, 1886) ranked the highest among terrestrial species, while the Critically Endangered Hawksbill Turtle and the Endangered Whale Shark Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828 ranked the highest in the ocean.

After identifying priority species for conservation, it is also essential to define strategies for conservation action. In these islands, so far only the Critically Endangered birds (Ndang’ang’a et al. 2014a, b—currently under review, Fundação Príncipe 2021c) and the Vulnerable Búzio-d’Obô (Panisi et al. 2020) have Species Action Plans dedicated to defining priority activities for conservation, further highlighting the long road ahead toward defining conservation priorities and implementing effective conservation action.

Site-Based Conservation

Several assessments have identified areas of global conservation relevance in the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea (Fig. 24.3). The islands include three Alliance for Zero Extinction sites: “Príncipe Forests” (5712 ha), “Sao Tome Uplands” (28,660 ha), and “São Tomé Lowland Forests” (21,833 ha—AZE 2019). These largely coincide with Key Biodiversity Areas (“Príncipe Forests”: 5708 ha; “São Tomé Montane and Cloud-forests”: 4839 ha; and “São Tomé Lowland Forests”: 21,832 ha—currently under review), of which there are five more on the islands: “Annobón” (2891 ha), “Tinhosas Islands” (18 ha), “São Tomé Northern Savannas” (526 ha), “Parque Natural Obô de São Tomé e Zona Tampão” (45,132 ha), and “Zona Ecológica dos Mangais do Rio Malanza” (231 ha—BirdLife International 2021c). The Tinhosas are a Ramsar site, due to their important seabird colony, as is the whole island of Annobón and surrounding waters (230 km2), mostly due to the threatened species and ecological assemblages it supports (Ramsar 2021). As part of the “Congolian Coastal Forests,” the “São Tomé, Príncipe and Annobón moist lowland forests” (WWF 2019) are listed as Critical or Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World (Olson and Dinerstein 2002) and have been identified among the most important ecoregion for the conservation of forest-dependent birds worldwide (Buchanan et al. 2011). Due to the unique assemblage of bird species, each of the main islands is a separate Endemic Bird Area, and they rank on the three highest priority categories of this assessment: São Tomé is critical, Príncipe is urgent, and Annobón is high (Stattersfield et al. 1998; BirdLife International 2021b). Since 2012, Príncipe has been recognized as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve that includes the Tinhosas, all other islets around the main island, and 576 km2 of surrounding marine environment (UNESCO 2021).

Map of sites prioritized for conservation in the oceanic islands of the Gulf of Guinea: (1) Príncipe Biosphere Reserve (UNESCO 2021); (2) São Tomé Key Biodiversity Areas (BirdLife International 2021c); (3) São Tomé Obô Natural Park, buffer zone and preliminary High Conservation Value areas (BirdLife International et al. 2020; UNEP-WCMC and IUCN 2021); (4) Annobón Nature Reserve (UNEP-WCMC and IUCN 2021). The nuclear terrestrial area of the Príncipe Biosphere Reserve corresponds to the Príncipe Natural Park, and the buffer corresponds to the buffer of the Natural Park. To the southwest of Príncipe Island, the marine protected areas demarcated around the Tinhosas Islets are a Ramsar site and a Key Biodiversity Area. The boundaries of the São Tomé lowland forests Key Biodiversity Area are not aligned with the contour of the island and will be revised in the ongoing national reassessment of Key Biodiversity Areas

As a result of its rich and productive marine life, the region has three Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas: “Tinhosas Islands,” “Lagoa Azul and Praia das Conchas,” and the “Equatorial Tuna Production Zone” (CBD 2021).

At the national level, each island has one protected area: the Annobón Natural Reserve, created in 2000 includes the whole island and surrounding marine environments (230 km2), the São Tomé Obô Natural Park (252 km2), and the Príncipe Obô Natural Park (45 km2), both created in 2006, the latter also including a strip of coastal ecosystems (Fig. 24.3, Appendix—UNEP-WCMC and IUCN 2021). The last two cover the wettest and most rugged portions of each island, where the best-preserved forests remain and are critical for the survival of many endemic species, especially the most threatened (e.g., de Lima et al. 2017; Soares 2017; Fundação Príncipe 2019; Soares et al. 2022). Taken together, they were assessed as the 32nd most important protected area in the world for the conservation of mammals, birds, and amphibians, the 17th if only threatened species are considered, and the 2nd ex aequo if only threatened bird species are counted (Le Saout et al. 2013). Unfortunately, despite having management plans (Albuquerque and Carvalho 2015a–d—currently under review) and receiving significant funding (Table 24.1), the effective implementation and success of both parks is lacking, largely due to a lack of stable and reliable sources of funding (BirdLife International 2019). A sustainable finance plan for protected areas and biodiversity is currently assessing best-revenue options, while several initiatives are already promoting implementation (Natural Strategies 2021). In São Tomé and Príncipe, the first efforts to create marine protected areas are only now taking place (Table 24.1—FFI et al. 2021).

There have been several national initiatives in recent years aimed at identifying additional areas that are relevant for conservation, beyond the strict concept of protected areas (Fig. 24.3). The laws that created both Obô Natural Parks (Appendix) envisaged the existence of a buffer zone, which would extend at least 250 m around the park boundaries, whenever possible, to work as a transition zone that would minimize the impact of human activities in the core protection area. These buffer zones are widely recognized and have received international funding (Table 24.1), but their boundaries and regulations were never clearly defined, and seem to have limited success at minimizing human impacts (Ward-Francis et al. 2017). Since 2018, BirdLife International has been leading the identification of High Conservation Values areas in São Tomé terrestrial and coastal ecosystems (BirdLife International et al. 2020), an initiative that is now being extended to Príncipe (D’Avis 2022). Since 2016, the Ministry of Infrastructures, Environment and Natural Resources of São Tomé and Príncipe, funded by the African Development Fund (Table 24.1) has been working on a national land planning initiative, which has identified large extents around the protected areas on each island as Conservation Areas (MIRNASTP 2021).

These initiatives should be continuously revised, since current knowledge on the distribution of biodiversity is still limited (Dauby et al. 2022; Soares et al. 2022). Ideally, these should be mostly based on the prioritization of ecosystem types to ensure that the best-preserved and most unique components of biodiversity are maintained. So far, the typification of ecosystems on the islands is not yet well established (Dauby et al. 2022). Areas at higher altitudes harbor endemic-rich and threatened ecosystems, even though biased sampling has limited our understanding of patterns along the altitudinal gradient (Stévart et al. 2022). The characterization and distribution of spatially restricted ecosystems, such as wetlands and coastal or rupicolous forests, constitutes a particularly pertinent challenge, since these hold specific plant associations (Diniz and Matos 2002; Dauby et al. 2022) and have unique ecologies that ensure key ecosystem services (e.g., Afonso et al. 2021) and thus deserve targeted conservation action. The peculiar palustrine system of Lagoa Amélia in São Tomé is one such example, holding several species that have highly restricted ranges (e.g., Stévart and Oliveira 2000) and the source of the springs that feed all main rivers in the north of the island. In this regard, the newly developed IUCN Red List for Ecosystems (Keith et al. 2015) might prove an invaluable tool.

Concluding Remarks

Príncipe, São Tomé, and Annobón are widely recognized as global priorities for biodiversity conservation, mostly due to their extraordinary number of endemic species. The value of their biodiversity is also promptly acknowledged by the islanders for the valuable services they provide and is engrained in the local culture. Nevertheless, the fast-growing population and economy, heavily reliant on the exploitation of natural resources, are threatening the long-term persistence of this precious natural heritage. Knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and investment in the conservation of the endemic-rich biodiversity of the islands have improved in recent decades but not fast enough to counteract the growth of anthropogenic pressure on natural resources. Remoteness and insularity, a colonial past and conflicting land tenure structures since independence, inadequate legal frameworks, weak institutional capacity to monitor and enforce laws, social inequity, and poor governance, all contribute to the environmental deregulation that threatens the biodiversity of the islands. While natural resources, like forests and fisheries are state-controlled in theory, high rates of non-compliance mean that these are de facto open access.

Although our knowledge of the biodiversity of the islands is still very incomplete, key priorities for conservation are mostly clear and should be the focus of future conservation activities. The exceptions are marine environments and Annobón, where biodiversity remains particularly understudied. Current knowledge must be used to expand the network of protected areas in marine and terrestrial environments, and to ensure effective protection of the best-preserved and keystone ecosystems. Likewise, management mechanisms that enhance the role of biodiversity for development, for instance through ecotourism, sustainable extraction of forest products, or payment for ecosystem services should be implemented. More broadly, biodiversity-friendly practices and alternative livelihoods should be mainstreamed into the economic and social development of communities to reduce pressure on natural resources by maintaining diverse agroforests, promoting sustainable levels of resource exploitation (e.g., fisheries, hunting, or timber logging), or even enhancing the biodiversity value of sites through business-based restoration mechanisms. More specific activities might also be necessary and highly beneficial for sensitive species or ecosystems, as is the case of restoring degraded wetlands, protecting sea turtle breeding sites, controlling invasive species, or even promoting conservation ex situ of highly threatened species.

There have also been an increasing number of initiatives aiming to improve environmental awareness on the islands (Ayres et al. 2022), which is vital to boost public support and locally-led initiatives, ultimately contributing toward more robust conservation. In addition, making biodiversity information more accessible (e.g., GBIF 2021) will strengthen local capacity and engagement in conservation. All these actions would benefit from continued research, but enough is already known to make biodiversity conservation a political priority and to improve conservation management.

The success of conservation on the islands will ultimately rely on public support, therefore it is pivotal to continue listening, informing, training, and engaging island inhabitants and institutions, to ensure that conservation projects are inclusive. Much has already been done in this regard, and conservation initiatives are increasingly moving toward integrating local needs and sensibilities, particularly through enhanced investment in in-country leadership for successful conservation. Nevertheless, there is still a difficult road ahead, as it is not always straightforward to balance biodiversity conservation with human needs to find truly sustainable development models. Reaching economic development and conservation goals must center on empowerment and equity, while considering trade-offs in a transparent and participatory approach. Only by promoting the involvement of diverse stakeholders working toward a shared vision, and through the co-development of integrative strategies, will we be able to ensure a thriving future for the unique biodiversity and human inhabitants of the islands.

References

Afonso F, Félix PM, Chainho P et al (2021) Assessing ecosystem services in mangroves: Insights from São Tomé Island (Central Africa). Frontiers in Environmental Science 9:501673

Albuquerque C, Carvalho A (2015a) Plano de gestão 2015/2016 do Parque Natural Obô de São Tomé. RAPAC, ECOFAC V, São Tomé, 57 pp

Albuquerque C, Carvalho A (2015b) Plano de gestão 2015/2016 do Parque Natural do Príncipe. RAPAC, ECOFAC V, São Tomé, 48 pp

Albuquerque C, Carvalho A (2015c) Plano de manejo 2015/2020 do Parque Natural Obô de São Tomé. RAPAC, ECOFAC V, São Tomé, 106 pp

Albuquerque C, Carvalho A (2015d) Plano de manejo 2015/2020 do Parque Natural do Príncipe. RAPAC, ECOFAC V, São Tomé, 73 pp

Alliance for Zero Extinction (AZE) (2019) Alliance for Zero Extinction. Available via: https://zeroextinction.org/. Accessed 29 Oct 2021

Almeida J, Fehn A-M, Ferreira M et al (2021) The genes of freedom: Genome-wide insights into marronage, admixture and ethnogenesis in the Gulf of Guinea. Genes 12:833

António M, Mata A, Cruz R (2021) Plano nacional de restauração florestal e paisagística—Uma avaliação de oportunidades de restauração. Direção das Florestas e da Biodiversidade, São Tomé

Associação Monte Pico (2021) Associação Monte Pico. Available via http://montepico.blogspot.com/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Associação Programa Tatô (2021) Associação Programa Tatô. Available via https://www.programatato.org/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Atkinson PW, Peet NB, Alexander J (1991) The status and conservation of the endemic bird species of São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa. Bird Conservation International 1:255–282

Ayres RGS, Aragão JCVC, Carvalho M et al (2022) Environmental education in São Tomé and Príncipe: the challenges of owning a unique biodiversity. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 671–690

Belhabib D (2015) Fisheries of Sao Tome and Principe, a catch reconstruction 1950-2010. University of British Columbia, Vancouver, 13 pp

Bell RC, Ceríaco LMP, Scheinberg LA, Drewes RC (2022) The amphibians of the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp. 479–504

BirdLife International (2019) Biodiversity and ecosystems in São Tomé and Príncipe. A short review. BirdLife International, São Tomé, 105 pp

BirdLife International (2021a) Avaliação rápida dos serviços ecossistémicos fornecidos pelos parques naturais de São Tomé e Príncipe e respetivas zonas tampão. ECOFAC6, São Tomé

BirdLife International (2021b) Endemic bird areas. Available via http://datazone.birdlife.org/eba. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

BirdLife International (2021c) The world database of key biodiversity areas. Available via Key Biodiversity Areas Partnership: BirdLife International, IUCN, Amphibian Survival Alliance, Conservation International, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, Global Environment Facility, Global Wildlife Conservation, NatureServe, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, World Wildlife Fund and Wildlife Conservation Society. http://www.keybiodiversityareas.org. Accessed 29 Sept 2021

BirdLife International (2021d) São Tomé & Príncipe strategic plan, 2021–2030. BirdLife International, São Tomé, 110 pp

BirdLife International, Direção-Geral do Ambiente, Associação Programa Tatô, cE3c (2020) Áreas de alto valor de conservação em São Tomé e Príncipe—Uma breve revisão. BirdLife International, São Tomé, 23 pp

Blue Action Fund (BAF) (2018) Grant fact sheet. Establishing a network of marine protected areas across São Tomé and Príncipe through a co-management approach. Available via Blue Action Fund. https://www.blueactionfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Factsheet_FFI.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Bonfim F, Castro A, Diogo O (2016) Estratégia e plano de acção nacional para o desenvolvimento do sector dos produtos florestais não lenhosos (PFNL). Ministério da Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural, São Tomé

Brito BR (2013) Alterações climáticas e suas repercussões sócio-ambientais. Associação Internacional de Investigadores em Educação Ambiental, Aveiro

Buchanan GM, Donald PF, Butchart SHM (2011) Identifying priority areas for conservation: a global assessment for forest-dependent birds. PLoS One 6:e29080

Campos E (1908) A ilha de S.Tomé. Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Lisboa

Carrasco N, Costa HP, Séca RM (2017) Plano multissectorial de investimentos de São Tomé e Príncipe. Integrar a resiliência às alterações climáticas e o risco de catástrofes na gestão da zona costeira. Banco Internacional para Reconstrução e Desenvolvimento, Associação Internacional para o Desenvolvimento, and Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, Washington, DC, 171 pp

Carvalho M (2015) Hunting and conservation of forest pigeons in São Tomé. PhD Thesis. University of Lisbon, Lisbon

Carvalho LLR, Baía OT (2012) Legislação ambiental de São Tomé e Príncipe. Available via https://chm.cbd.int/api/v2013/documents/7A589779-9AEE-D35A-2169-2D5886F70A72/attachments/LEGISLACAO-AMBIENTAL-DE-SAO-TOME-E-PRINCIPE.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Carvalho M, Rego F, Palmeirim J, Fa JE (2015a) Wild meat consumption on São Tomé Island, West Africa: Implications for conservation and local livelihoods. Ecology and Society 20:27

Carvalho M, Palmeirim JM, Rego F, Solé N, Santana A, Fa JE (2015b) What motivates hunters to target exotic or endemic species on the island of São Tomé, Gulf of Guinea? Oryx 49:278–286

Carvalho SP, Mata AT, António M (2017) Plano nacional de desenvolvimento florestal. Proposta. Direção das Florestas e da Biodiversidade, São Tomé

Carvalho I, Pereira A, Martinho F et al (2022) Cetaceans of São Tomé and Príncipe. In: Ceríaco LMP, de Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: Science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 621–642

CBD (2021) Ecologically or biologically significant marine areas. Available via https://www.cbd.int/ebsa/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

CEPF (2021) Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. Sao Tome and Principe projects Available via https://www.cepf.net/grants/grantee-projects?f[]=field_hotspot:14&f[]=field_countries:1112. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Ceríaco LMP, Santos BS, Lima RF et al (2022a) Physical geography of the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 13–36

Ceríaco LMP, Santos BSS, Viegas S, Paiva J (2022b) The history of biological research in the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 87–140

Ceríaco LMP, Marques MP, Bell RC, Bauer AM (2022c) The terrestrial reptiles of the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 505–534

Costa LM, Maia HA, Almeida AJ (2022) The fishes of the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 431–478

Cravo MM (2021) Fish assemblages at Praia Salgada mangrove, Príncipe Island (Gulf of Guinea). MSc Thesis. University of Lisbon, Lisbon

Cruz GSPV (2014) A democracia em S. Tomé e Príncipe, instabilidade política e as sucessivas quedas dos governos. MSc thesis. ISCTE—Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisbon

Darwin Initiative (2021) Darwin Initiative. Omali Vida Nón. Available via https://www.darwininitiative.org.uk/project/DAR23012. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Dauby G, Stérvart T, Barberá P et al (2022) Classification, distribution, and biodiversity of terrestrial ecosystems in the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 37–70

D’Avis KV (2022) Spatial conservation prioritization on the endemic-rich island of Príncipe. MSc Internship report. University of Lisbon, Lisbon

Desjardin DE, Perry BA (2022) Fungi of São Tomé and Príncipe Islands: Basidiomycte mushrooms and allies. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 189–216

Dias AMP (2013) De piroga não se pesca ao largo! Acordo de parceria no domínio das pescas entre a União Europeia e a República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe: Quais os benefícios para a pesca artesanal santomense?. MSc Thesis. ISCTE-Instituto Universitário de Lisboa, Lisbon

Diniz AC, Matos GC (2002) Carta da zonagem agro-ecológica e da vegetação de S. Tomé e Príncipe. Garcia de Orta, Série Botânica 15:1–72

Espírito ADA, António MDR, Mata AT, Lima RF (2020) Toward sustainable logging in São Tomé, São Tomé and Príncipe—Final Report. Conservation Leadership Programme, São Tomé, p 16

ECOFAC6 (2021) Programme ECOFAC6. Available via https://www.ecofac6.eu/fr. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

EDGE (2021) Evolutionarily distinct globally endangered. Available via https://www.edgeofexistence.org/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

European Commission (EC) (2021) ECOFAC6—Preserving biodiversity and fragile ecosystems in Central Africa. Available via https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/programmes/ecofac6_en. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

European Union (EU) (2021) 11e FED—Action pour la gestion durable des paysages à São Tomé e Príncipe—2020. Available via https://www.welcomeurope.com/calls-projects/11e-fed-action-pour-la-gestion-durable-des-paysages-a-sao-tome-e-principe-2020/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Exell AW (1944) Catalogue of the vascular plants of S. Tomé (with Príncipe and Annobón). British Museum, London, 428 pp

Eyzaguirre PB (1986) Small farmers and estates in São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa. PhD Thesis. Yale University, New Haven

FAO (2019) Estudo do sector dos produtos do mar em São Tomé e Príncipe: Descrição qualitativa/quantitativa das cadeias de abastecimento e de valor. FAO, São Tomé, 74 pp

Fauna & Flora International (2021) Fauna & Flora International. Sao Tome and Principe. Available via https://www.fauna-flora.org/countries/sao-tome-principe. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Fauna & Flora International, Fundação Príncipe, Oikos et al (2021) Omali Vida Nón. Available via https://omaliprincipeen.weebly.com/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Ferreira-Airaud B, Schmitt V, Vieira S et al (2022) The sea turtles of São Tomé and Príncipe: diversity, distribution and conservation status. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 535–554

Flood RL, Lima RF, Melo M, Verbelen P, Wagstaff WH (2019b) What is known about the enigmatic Gulf of Guinea band-rumped storm petrels Hydrobates cf. castro? Bull Br Ornithol Club 139:173–186

Frynas JG, Wood G, Oliveira RMSS (2003) Business and politics in São Tomé e Príncipe: From cocoa monoculture to petro-state. African Affairs 10:51–80

Fundação Príncipe (2019) Understanding the remarkable biodiversity of Príncipe Island. Scientific Report. Fundação Príncipe, Santo António, 33 pp

Fundação Príncipe (2021a) Fundação Príncipe. Projeto Protetuga. Available via https://fundacaoprincipe.org/projetos/conservacao-marinha/protetuga. Accessed 12 Nov 2021

Fundação Príncipe (2021b) Fundação Príncipe. Available via https://fundacaoprincipe.org/. Accessed 12 Nov 2021

Fundação Príncipe (2021c) Single species action plan for the conservation of the Principe Thrush, 2020-2024. Fundação Príncipe, Santo António

Fundação Príncipe (2021d) Projecto Omali Vida Nón. Available via https://fundacaoprincipe.org/projetos/conservacao-marinha/omali-vida-non. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Fundação Príncipe, Missouri Botanical Garden, University of Coimbra (2021) Flora Ameaçada. Available via https://cepf-stp-threat-flora.netlify.app/. Accessed 12 Nov 2021

García JE, Eneme F (1997) Diagnóstico de las áreas críticas para la conservación. Componente unidades de conservación. CUREF, Bata, 88 pp

Garcia C, Sérgio C, Shevock JR (2022) The bryophyte flora of São Tomé and Príncipe (Gulf of Guinea): past, present and future. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 217–248

Gascoigne A (1995) The red data list of threatened animals of São Tomé e Príncipe. ECOFAC–Composante de STP, São Tomé, 15 pp

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) (2021) Unlocking data on plant biodiversity for decision-making in São Tomé and Príncipe. Available via https://www.gbif.org/project/BID-AF2020-127-INS/unlocking-data-on-plant-biodiversity-for-decision-making-in-sao-tome-and-principe. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Global Environment Facility (GEF) (2021) Global Environment Facility projects. Available via https://www.thegef.org/projects. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Gonçalves I, de Lima CD, Brito P (2014) Sabores da nossa terra. N’ga cumé quá téla non. ONG Alisei STP, São Tomé, 198 pp

Gulf of Guinea Biodiversity Center (GGBC) (2021) Gulf of Guinea Biodiversity Center. Available via https://gulfofguineabiodiversity.org/. Accessed 17 Oct 2021

Hagemeijer T, Rocha J (2019) Creole languages and genes: The case of São Tomé and Príncipe. Faits de Langues 49:167–182

Heleno RB, Mendes F, Coelho AP et al (2022) The upsizing of the São Tomé seed dispersal network by introduced animals. Oikos. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08279

Henriques JA (1917) A ilha de São Tomé sob o ponto de vista histórico-natural e agrícola. Boletim da Sociedade Broteriana 27:1–197

INEGE (2018) Resultados preliminares del IV censo de población 2015. INEGE, Malabo, 16 pp

INESTP (2019) Projecção a nível distrital 2012-2020. Available via INESTP. https://ine.st/index.php/component/phocadownload/file/270-projeccao-a-nivel-distrital-2012-2020. Accessed 22 Oct 2021

IUCN (2021) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Version 2020-2. Available via International Union for Conservation of Nature. https://www.iucnredlist.org. Accessed 22 Oct 2021

Jones PJ (1994) Biodiversity in the Gulf of Guinea: An overview. Biodiversity and Conservation 3:772–784

Jones PJ, Tye A (1988) A survey of the avifauna of São Tomé and Príncipe. Study Report 24. International Council for Bird Preservation, Cambridge, UK

Jones PJ, Tye A (2006) The birds of São Tomé and Príncipe, with Annobón: Islands of the Gulf of Guinea. British Ornithologists’ Union, Oxford

Jones PJ, Burlison JP, Tye A (1991) Conservação dos ecossistemas florestais na República Democrática de São Tomé e Príncipe. UICN, Gland, Cambridge, UK, 78 pp

Juste JB, Fa JE (1994) Biodiversity conservation in the Gulf of Guinea islands: taking stock and preparing action. Biodivers Conserv 3:759–771

Keith DA, Rodríguez JP, Brooks TM et al (2015) The IUCN Red List of Ecosystems: Motivations, challenges and applications. Conservation Letters 8:214–226

Lee PW, Liu CT, do Rosario VE et al (2010) Potential threat of malaria epidemics in a low transmission area, as exemplified by São Tomé and Príncipe. Malaria Journal 9:264

Le Saout S, Hoffmann M, Shi Y et al (2013) Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation. Science 342:803–805

Lima RF (2012) Land-use management and the conservation of endemic species in the island of São Tomé. PhD thesis. Lancaster University, Lancaster

Lima RF (2016) Biodiversity conservation in São Tomé and Príncipe: an overview. In: Gabriel R, Elias RB, Amorim IR, Borges PAV (eds) Conference program and abstracts of the 2nd International Conference on Island Evolution, Ecology and Conservation: Island Biology 2016, 18–22 July 2016, Angra do Heroísmo, Azores, Portugal, 18–22 July 2016. Arquipélago Life Mar Sci Suppl 9:136

Lima RF, Sampaio H, Dunn JC et al (2017) Distribution and habitat associations of the critically endangered bird species of São Tomé Island (Gulf of Guinea). Bird Conserv Int 27:455–469

Madureira MCTMB, Paiva J, Fernandes AF et al (2008) Estudo etnofarmacológico de plantas medicinais de S. Tomé e Príncipe. Ministério da Saúde de S. Tomé e Príncipe, São Tomé, 217 pp

Maia HA, Morais RA, Siqueira AC, Hanazaki N, Floeter SR, Bender MG (2018) Shifting baselines among traditional fishers in São Tomé and Príncipe islands, Gulf of Guinea. Ocean and Coastal Management 154:133–142

MAPDRSTP (2010) Plano diretor das pescas. Ministério da Agricultura, Pesca e Desenvolvimento Rural, São Tomé

MARAPA (2021a) MARAPA—Mar, Ambiente e Pesca Artesanal. Available via https://sites.google.com/site/marapastp/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

MARAPA (2021b) Operação Tunhã. Available via https://sites.google.com/site/operacaotunha/home. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Melo M (2012) A biodiversidade de São Tomé e Príncipe ficou mais pobre. Téla Nón May 4, 2012. https://www.telanon.info/sociedade/2012/05/04/10321/a-biodiversidade-de-sao-tome-e-principe-ficou-mais-pobre/

Melo M, Jones PJ, Lima RF (2022) The avifauna of the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell R (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 555–592

MIRNASTP (2021) Plano Nacional de Ordenamento de Território. São Tomé e Príncipe. Available via http://pnot.gov.st/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Muñoz-Torrent X, Trindade NT, Mikulane S (2022) Territory, economy, and demographic growth in São Tomé and Príncipe: anthropogenic changes in environment. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 71–86

Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, Fonseca GAB, Kent J (2000) Biodiversity hotspot for conservation priorities. Nature 403:853–858

NAPA (2006) Plano de acção cacional para adaptação as mudanças climáticas. Ministério de Recursos Naturais e Ambiente, São Tomé, 76 pp

Natural Strategies (2021) Sustainable finance plan for biodiversity and protected areas in São Tomé and Príncipe. BirdLife International, ECOFAC6, São Tomé

Ndang’ang’a PK, Ward-Francis A, Costa L et al (2014a) International action plan for conservation of Critically Endangered birds on São Tomé. 2014-2018. BirdLife International, São Tomé, 30 pp

Ndang’ang’a PK, Melo M, Lima RF et al (2014b) Single species action plan for the conservation of the Príncipe thrush Turdus xanthorhynchus. 2014–2018. BirdLife Int, São Tomé, p 15

NGANDU (2021) NGANDU—The importance of shark populations and sustainable ocean use for human well-being in Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe, West Africa. Available via http://www.ruirosalab.com/ngandu.html. Accessed 16 Nov 2021

Norder SJ, Lima RF, Nascimento L et al (2020) Global change in microcosms: environmental and societal predictors of land cover change on the Atlantic Ocean Islands. Anthropocene 30:100242

Nuno A (2019) Omali vida nón—Summary of project activities and preliminary results. University of Exeter, Exeter, 24 pp

Nuno A (2021) Caracterização da cadeia de valor do carvão vegetal em São Tomé e Príncipe e avaliação de riscos de deslocamento económico no âmbito de iniciativas relacionadas com sustentabilidade florestal. PNUD, DGASTP, Birdlife International, São Tomé, 93 pp

Nuno A, Matos L, Metcalfe K, Godley BJ, Broderick AC (2021) Perceived influence over marine conservation: Determinants and implications of empowerment. Conservation Letters 14:e12790

NYBG (2021) Index Herbariorum. STPH. Herbário Nacional of São Tomé e Príncipe. Available via http://sweetgum.nybg.org/science/ih/herbarium-details/?irn=150668. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Oikos (2021) Oikos—Cooperação e Desenvolvimento. São Tomé e Príncipe. Available via https://www.oikos.pt/pt/onde-estamos/sao-tome-e-principe. Accessed 12 Oct 2021.

Oikos and MARAPA (2021) Kike da mungu. Cogestão sustentável de pescas no sul da ilha de São Tomé. Available via https://kikedamungu.weebly.com/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Olson DM, Dinerstein E (2002) The Global 200: Priority ecoregions for global conservation. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 89:199–224

Osono SFE, Ondó AM, Núñez PF (2015) Estrategia nacional y plan de acción para la conservación de la diversidad biológica. Dirección General Medio Ambiente, Ministerio de Pesca y Medio Ambiente, Malabo

Oyono PR, Morelli TL, Sayer J et al (2014) Allocation and use of forest land: Current trends, issues and perspectives. In: Wasseige C, Flynn J, Louppe D, HiolHiol F, Mayaux P (eds) The forests of the Congo Basin—State of the forest 2013. Weyrich, Neufchâteau, pp 215–240

Panisi M, Sinclair F, Santos Y (2020) Single species action plan for the conservation of the Obô Giant Snail Archachatina bicarinata, 2021-2025. IUCN SSC Mid-Atlantic Island Invertebrate Specialist Group, São Tomé, 22 pp

Panisi M, Pissarra V, Oquiongo G, Palmeirim JM, Lima RF, Nuno A (2022) An endemic-rich island through the eyes of children: wildlife identification and conservation preferences in São Tomé (gulf of Guinea). Conserv Sci Pract. https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.12630

Pereira ARC (2021) The socio-economic importance of the invasive West African Giant Land Snail (Archachatina marginata) in São Tomé Island. MSc Thesis. University of Lisbon, Lisbon

Polidoro BA, Ralph GM, Strongin K et al (2017) The status of marine biodiversity in the Eastern Central Atlantic (West and Central Africa). Aquatic Conservation. Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 27:1021–1034

Porriños G (2021) Characterisation of artisanal fisheries in São Tomé and Príncipe through participatory, smartphone-based landing surveys. Project report. Available via http://www.gporrinos.com/resources.html. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Rainho A, Meyer CFJ, Thorsteinsdóttir S et al (2022) Current knowledge and conservation of the wild mammals of the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 593–620

Ramsar (2021) Ramsar Sites Information Service. Ilots Tinhosas. Available via https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/1632?language=en. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

RDSTP (1998) Plano acional do ambiente para o desenvolvimento durável (1998-2008). Governo de São Tomé e Príncipe, São Tomé

Rede.Bio (2021) Rede.Bio. Available via https://redebiostp.weebly.com/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Roberts CM, McClean CJ, Veron JEN et al (2002) Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science 295:1280–1284

Roseira LL (1984) Plantas úteis da flora de S. Tomé e Príncipe. Medicinais, industriais e ornamentais. Serviços Gráficos da Liga dos Combatentes, Lisboa 100 p

Rufford Foundation (2021) The Rufford Foundation. São Tomé and Príncipe. Available via https://www.rufford.org/projects/?continent=africa&q=sao+tome&sort_by=-created. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Salgueiro A, Carvalho S (2001) Proposta de plano nacional de desenvolvimento florestal 2003-2007. ECOFAC, AGRECO, CIRAD Forêt, São Tomé

Seibert G (2016) São Tomé e Príncipe 1975-2015: Política e economia numa antiga colônia de plantação. Estudos Ibero-Americanos 42:987–1012

Soares FC (2017) Modelling the distribution of São Tomé bird species: Ecological determinants and conservation prioritization. MSc Thesis. University of Lisbon, Lisbon

Soares FC, Hancock JM, Palmeirim JM et al (2022) Species ecology in the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands: distribution, habitat preferences, assemblages and interactions. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 171–188

Soulé ME (1985) What is conservation biology? BioScience 35:727–734

Stattersfield AJ, Crosby MJ, Long AJ, Wedge DC (1998) Endemic bird areas of the world: priorities for biodiversity conservation. BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK

Stévart T, Oliveira F (2000) Guide des orchidées de São Tomé et Príncipe. ECOFAC, São Tomé

Stévart T, Dauby G, Ikabanga DU et al (2022) Diversity of the vascular plants of the Gulf of Guinea oceanic islands. In: Ceríaco LMP, Lima RF, Melo M, Bell RC (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: science and conservation. Springer, Cham, pp 249–272

Torres  (2005) Mionga ki ôbo: Mar e selva. LX Filmes, Lisboa

UNDP (2001) Plano estratégico para o desenvolvimento do turismo em São Tomé e Príncipe. PNUD, Madrid

UNDP (2019) Príncipe 2030. Sustainable Development Plan for the Autonomous Region of Príncipe. Available via https://en.principe2030.com/. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

UNEP-WCMC and IUCN (2021) Protected planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) and World Database on Other Effective Area-based Conservation Measures (WD-OECM). Available at: www.protectedplanet.net. Accessed 16 Oct 2021

UNESCO (2021) Biosphere reserves. Island of Principe Biosphere Reserve, Sao Tome and Príncipe. Available via https://en.unesco.org/biosphere/africa/island-of-principe. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

Valverde P (2000) Máscara, mato e morte em São Tomé. Celta, Lisboa

Vié J-C, Hilton-Taylor C, Stuart SN (2009) Wildlife in a changing world—an analysis of the 2008 IUCN red list of threatened species. IUCN, Gland, 180 pp

Ward-Francis A, Lima RF, Sampaio H, Buchanan G (2017) Reducing the extinction risk of the three critically endangered birds of São Tomé. Final project report. BirdLife International, Cambridge, UK

Wendling ZA, Emerson JW, Sherbinin A et al (2020) 2020 environmental performance index. Available via Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. https://epi.yale.edu/epi-results/2020/country/stp. Accessed 21 Oct 2021

Wirtz P, Ferreira CEL, Floeter SR et al (2007) Coastal fishes of São Tomé and Príncipe islands, Gulf of Guinea (eastern Atlantic Ocean)—an update. Zootaxa 1523:1–48

Wood (2004) Business and politics in a criminal state: The case of Equatorial Guinea. African Affairs 103:547–567

WWF (2019) Ecoregions. Islands of São Tomé and Príncipe of the coast of Equatorial Guinea. Availabe via https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/at0127. Accessed 12 Oct 2021

WWF and IUCN (1994) Centres of plant diversity: A guide and strategy for their conservation. Volume 1: Europe, Africa, South West Asia and the Middle East. IUCN, Gland

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Bastien Loloum, Betânia Ferreira-Airaud, David Bruguière and Muriel Vives for sharing information used to create Table 24.1, and Angela Formia for sharing information on Annobón. RFL benefitted from cE3c structural funding by the Portuguese Government through “Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia” (FCT/MCTES – UID/BIA/00329/2021), who also supported SV with a PhD grant (SFRH/BD/05970/2020). AN acknowledges the support of the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement SocioEcoFrontiers No. 843865.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: International Agreements and National Legislation and Strategies Relevant to Biodiversity Conservation

Appendix: International Agreements and National Legislation and Strategies Relevant to Biodiversity Conservation

International agreements adhered to by the Democratic Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe (STP) and the Republic of Equatorial Guinea (EG):

-

Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992 – STP; 2000 – EG)

-

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (1992 – EG; 2001 – STP)

-

Convention to Combat Desertification (1994 – EG; 1995 – STP)

-

Convention on Biological Diversity (1995 – EG; 1998 – STP)

-

Kyoto Protocol (2000 – EG; 2008 – STP)

-

Bonn Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (2001 – STP; 2010 – EG)

-

Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat (2003 – EG; 2006 – STP)

-

Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (2006 – STP; 2010 – EG)

-

Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing (2016—STP)

-

Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (2017 – STP)

Biodiversity conservation legislation—STP (Carvalho and Baía 2012):

-

Law 10/99 – Basic Law for the Environment

-

Law 11/99—Conservation of Fauna, Flora and Protected Areas

-

Decree-Law 37/99—Environmental Impact Assessment Process

-

Law 5/01—Forests

-

Law 9/11—Fisheries and Fishery Resources (currently under revision)

-

Law 6/06—São Tomé Obô Natural Park

-

Law 7/06—Príncipe Obô Natural Park

-

Regional Decree 3/09—Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles

-

Decree Law 6/14—Capture and commercialization of sea turtles and their products

-

Decree Law 1/16—Hunting regulation

Biodiversity conservation legislation—EG (Osono et al. 2015):

-

Law 8/88—Wild Fauna, Hunting, and Protected Areas

-

Law 1/97—Forest Use and Management

-

Law 1/00—Taxation on timber exports

-

Law 4/00—Protected Areas

-

Law 7/03—Environment

-

Law 10/03—Fishing

-

Law 3/07—Water and Coasts

-

Law 4/09—Land tenure

-

Decree Law 130/04—Fishing

-

Decree Law 171/05—Biodiversity Conservation National Strategy and Action Plan

-

Decree Law 172/05—Trade of wild threatened species of flora and fauna

-

Decree Law 173/05—Environmental inspection

-

Decree Law 61/07—Timber exportation

-

Decree Law 72/07—Primate hunting, selling, consumption, and ownership

-

Decree 60/02—National Institute for Forest Development and Management of the National Protected Area Network

National strategies for biodiversity conservation—STP:

-

National Environmental Plan for Sustainable Development (RDSTP 1998)

-

Strategic Plan for Tourism Development (UNDP 2001)

-

National Forest Development Plan (Salgueiro and Carvalho 2001; Carvalho et al. 2017)

-

National Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation (NAPA 2006)

-

Fisheries Master Plan (MAPDRSTP 2010)

-

Strategy and National Action Plan for Developing the Sector of Non-Timber Forest Products (Bonfim et al. 2016)

-

Multisectoral Investment Plan to Integrate Climate Change Resilience and the Risk of Catastrophes in Coastal Management (Carrasco et al. 2017)

-

National Land Use Plan (MIRNASTP 2021)

-

Sustainable Development Plan for the Autonomous Region of Príncipe: Príncipe 2030 (UNDP 2019)

-

National Plan for Forest and Landscape Restoration (António et al. 2021)

National strategies for biodiversity conservation—EG (Osono et al. 2015):

-

2020 National Plan for Economic and Social Development

-

National Plan for Environmental Management

-

Biodiversity Conservation National Strategy and Action Plan

-

National Land Use Plan

-

National Protected Area Network

-

National Forest Policy Plan

-

National Climate Change Adaptation Plan

-

National Action Plan for Coastal and Marine Ecosystems

-

National Hydrological Plan

-

National Education Plan

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

de Lima, R.F., Deffontaines, JB., Madruga, L., Matilde, E., Nuno, A., Vieira, S. (2022). Biodiversity Conservation in the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands: Recent Progress, Ongoing Challenges, and Future Directions. In: Ceríaco, L.M.P., de Lima, R.F., Melo, M., Bell, R.C. (eds) Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06153-0_24

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06153-0_24

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-06152-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-06153-0

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)