Abstract

Pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behavior have lagged behind the already sparse treatments for suicidal adults, leaving many at-risk youths undertreated. The following is a review of the neurobiological research literature focused on suicide risk in children and adolescents. Topics include the relationship of suicide risk to neuroimaging findings, impulsivity, genetics, and treatment approaches, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), lithium, ketamine, and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS).

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

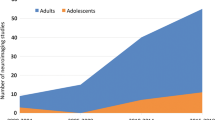

Emergency department visits for youth suicidal thoughts and behaviors are on the rise (Kalb et al., 2019), with the full impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates still unknown. Given all that is at stake, children and adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors need effective treatments. To maximize their effectiveness, clinicians will benefit from a range of treatments that are rapid, safe, and tailored to the specific clinical and biological needs of each patient. Unfortunately, regardless of age, there are few rapid pharmacologic or non-pharmacologic treatments that have demonstrated immediate or lasting impact on suicidal thoughts and behavior. Options are even more limited for medication treatments for children and adolescents with suicidal thoughts, in part due to understandable concerns around enrolling minors into clinical trials with potentially negative and long-term effects on adolescent physiology and brain development. This cautious approach places clinicians in an untenable situation; they are asked to emergently treat youth with suicidal thoughts and behavior but do not have the requisite clinical tools and evidence-based standards from research. Consequently, clinicians cannot provide many suicidal youth with needed treatments without evidence-based guidance from potentially high-risk research and clinical trials. What follows is an overview of specific neurobiological and pharmacologic research focused on suicide risk and treatment. When possible, we highlight the particular needs of adolescents as distinct from adults in critical areas for future research.

Neurobiological Research of Adolescents at Risk of Suicide

First, any discussion of the neurobiology of suicide in adolescents should consider the role of brain development. The human brain does not fully mature until around age 24 years (Gogtay et al., 2004). Between childhood and adulthood, the adolescent brain undergoes many changes that place adolescents at unique risk for impulsive emotional behavior. For example, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which is involved in planning, impulse control, and executive functioning, is one of the last brain areas to fully mature and appears to develop at different rates in males and females (Hammerslag & Gulley, 2016). In contrast, limbic regions associated with emotional reactivity, such as the nucleus accumbens and amygdala, are fully matured in adolescence (Casey et al., 2008). Thus, the adolescent brain is “wired” to have strong emotional reactions, particularly to interpersonal interactions, at a time when their ability to plan and control impulses is less developed. This tendency toward reactive behaviors puts adolescents, particularly males, at risk for impulsive suicidal behavior. Research around functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and adolescent suicide attempters has mostly focused on reactions to emotional stimuli, for example, brain reactivity to perceived angry faces or social exclusion (Harms et al., 2019). Overall, neuroimaging studies suggest that adolescents with a history of suicide attempt show altered neural activity in areas related to emotional processing. One analysis of adolescent suicide attempters, as compared to non-attempters with bipolar disorder, showed reduced functional connectivity between the amygdala (part of limbic system) and PFC associated with suicide attempt lethality and suicide ideation severity (Johnston et al., 2017). Thus, adolescents at highest suicide risk may have altered connectivity between the emotional (limbic) and self-control regions (PFC) of the brain. These changes in brain connectivity represent potential targets for future intervention whether through learning strategies for emotional coping in psychotherapy to strengthen these brain pathways or by impacting the neural connectivity underlying decision-making through pharmacologic or neuromodulation strategies (e.g., transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)).

Second, there are genetic influences on suicidal behavior that place certain adolescents at higher risk of suicide. Family studies have indicated that children of parents with a suicide attempt history are at increased likelihood of suicide attempt, possibly due to influence of impulsive aggression, inheritance of mood disorders, or environmental exposures to suicidal behavior (Brent et al., 2015; Kendler et al., 2020). While there is unlikely to be a specific “gene” associated with suicide risk, analyses that take into account the influence of many genes, termed “polygenic risk scores,” are currently in use to evaluate the multifactorial impact of genetic risk on suicidal behavior. In one example, polygenic risk scores for bipolar disorder predicted risk for suicide attempt in a sample of adolescents and young adults but only in the context of a traumatic stress history (Wilcox et al., 2017). Clearly, both genetic and environmental factors interact in the development of adolescent suicidal behavior within families. These factors suggest possible opportunities for targeted intervention. For example, future programs could treat offspring of parents who attempt suicide to determine whether such intervention impacts later suicidal thoughts and behaviors, particularly for individuals with both parental suicidal behavior and traumatic event experiences.

The next generation of interventions based on current neurobiological research suggests that it may be important to intervene with certain patient groups before they make their first suicide attempt, namely, individuals with impulsivity or familial suicidal behavior. Additionally, it will be critical to understand the behavioral manifestations of these neurobiological markers. For example, adolescents with altered connectivity between emotional and self-control regions of the brain could be evaluated using technologies such as ecological momentary assessment (EMA), which typically involves the repeated assessment of current experiences on smartphone devices (Shiffman et al., 2008), in order to obtain a “real-time” observation of emotional reactivity and impulsivity. Similarly, individuals with parental suicidal behavior could be evaluated using measures of implicit suicide risk, which assess biases toward death and suicide-related stimuli (Nock et al., 2010). By incorporating these exciting new technologies with neurobiological measures, researchers can target their treatments to where it is most needed in order to prevent later suicidal behavior (see also Wang et al., Chap. 3, this volume).

Barriers and Opportunities for Pharmacologic Treatment

Clinical trials for suicide risk are critical but difficult to conduct due to ethical and clinical concerns of enrolling and monitoring individuals at risk for suicide. These concerns are further compounded in trials involving adolescents due to concerns about minor assent/parent consent, adherence to treatment regimens, the possible negative impact of interventions on brain development and long-term consequences, as well as the aforementioned tendency of adolescents to engage in impulsive behavior. As such, adequately powered studies designed to evaluate pharmacologic treatment outcomes for suicidal adolescents are uncommon. The following section discusses two areas relevant to expanding opportunities for effective pharmacologic treatment: (1) understanding the impact of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) “black box” warning for suicide risk and (2) strategies to expand emerging research.

In the early 2000s, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) received reports from pharmaceutical companies that SSRIs, commonly prescribed for depression, were associated with increased risk of suicide attempt in adolescents. These reports led to further FDA investigation and a 2004 black box warning for the use of SSRIs in children and adolescents, due to concerns for suicide risk in youth up to 24 years of age with clear drug efficacy in older adults (for a full account of the FDA evaluation, please see Hammad et al., 2006). This black box warning has been associated with significant controversy; reanalysis of the randomized clinical trial (RCT) data by different groups has reported inconsistent results and questionable coding of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Posner et al., 2007). What is known is that antidepressant prescription rates for children and adolescents sharply fell after this warning (Lu et al., 2014). This drop in prescriptions has been linked to increased adolescent suicide rates suggesting that depressed and suicidal adolescents were no longer receiving needed treatments, although there is also contentious debate about this relationship (Gibbons et al., 2007). Delineating the underlying relationship between SSRIs and suicide is well beyond the scope of this review but does highlight the following principles: (1) a positive relationship between SSRIs and suicide risk is not found for adults, emphasizing the need to evaluate the efficacy and safety of pharmacologic treatments in adolescent samples; and (2) prescribing any psychiatric medication to a child or adolescent requires careful monitoring and extensive documentation, particularly in the first few weeks of treatment. One major concern is that the SSRI black box warning has deterred further pharmacologic investigations into suicide-focused treatments especially for youth. Sadly, research in adult depression clinical trials has suggested that individuals with suicidal thoughts and behaviors are also now more likely be excluded from research (Zimmerman et al., 2015), even as suicide rates continue to increase. We propose that suicide-focused clinical trials in adolescents are needed now more than ever and that concerns around the need for enhanced observation, assessment, and media scrutiny do not outweigh the benefits of preventing death by suicide.

In the absence of such evidence-based treatments, clinicians may consider other off-label treatments. Clozapine, the only FDA-approved medication for the treatment of suicide attempt, is primarily prescribed for the treatment of schizophrenia, has several major side effects, and is rarely used in children and adolescents. Lithium has been associated with reduced suicide attempt rates and aggression in a sample of children and adolescents with bipolar disorder, (Hafeman et al., 2020) but is not FDA approved for suicidal behavior in any age group. Newer treatments, ketamine and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are currently being evaluated for adults; if effective, these will require careful additional evaluation in adolescent populations. Ketamine has a history of being used medically as a dissociative anesthetic but also as a drug of abuse. Subanesthetic intravenous administrations of ketamine are associated with transient reductions in suicidal thoughts within minutes to hours. Initial open-label trials of ketamine have been conducted in adolescents (Cullen et al., 2018), but research is proceeding with understandable caution due to concerns of substance abuse and potential effects on the developing adolescent brain. Even with a sufficient evidence base, a provider might weigh the benefits of transient relief of intractable suicidal thoughts and depression in an at-risk youth with concerns that the individual might then pursue further ketamine administrations to the detriment of other effective pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic therapies. Similarly, TMS involves the noninvasive direct stimulation of the brain using magnetic pulses. While there is an established literature on TMS for depression, which has recently expanded to include initial open-label trials of TMS in adolescents with depression and suicidal thoughts, concerns remain about permanent neural alterations (Croarkin et al., 2018). Therefore, while promising treatments may be on the horizon, clinicians treating at-risk youth have limited pharmacologic resources at their disposal and often must weigh the concerns of treating imminent suicide risk with off-label use of psychiatric medications without a clear evidence base.

Comprehensive evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors are essential. Carefully designed and monitored clinical trials of treatments such as lithium, ketamine, and TMS in adolescents could inform future prescribing practices to understand which individuals are most likely to benefit from which treatments as well as potential side effects. Since it is likely that most youth with suicidal thoughts and behaviors are prescribed medications off-label, standardized patient registries and protocols may be needed for a complete understanding of the potential effects (and unintended side effects) of these treatments. In short, more data on the effects of pharmacologic treatments for adolescents at risk for suicide is necessary for clinicians to aid their clinical decision-making.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Adolescence represents a critical period in development during which the brain is most reactive to emotional stimuli but vulnerable due to underdeveloped planning and impulse control. Furthermore, genetic predisposition and environmental stressors can put an adolescent at additional risk for suicide. Due to key brain changes that occur over the course of early development, it cannot be assumed that treatments for suicide that are efficacious for adults will show similar effects in adolescents. In addition, because of safety concerns, clinical treatment trials in adolescents have been limited. As such, it is likely that suicidal adolescents are undertreated, resulting in a clear call-to-action to develop research studies and clinical trials focused on neurobiological risk factors and treatment targets in adolescents. First, neurobiological research points to areas of intervention before a child or adolescent makes a first suicide attempt, namely, individuals with impulsivity and/or familial suicide risk. Second, for individuals already experiencing suicidal thoughts and behavior, clinical trials are critically needed to understand which treatments provide the most benefit, potentially incorporating new modes of data collection that monitor real-time active and implicit suicide risk. Policy recommendations include providing guidance to ethical review boards on how to evaluate research and clinical trials with suicidal youth as well as disseminating resources to support psychiatrists and primary care practitioners on the effective treatment of youth at risk for suicide including best practice care pathways and treatment algorithms. Without such research and resources, adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors will continue to be undertreated, putting them at further risk of distress, suicidal behavior, and death.

References

Brent, D. A., Melhem, N. M., Oquendo, M., Burke, A., Birmaher, B., Stanley, B., Biernesser, C., Keilp, J., Kolko, D., Ellis, S., Porta, G., Zelazny, J., Iyengar, S., & Mann, J. J. (2015). Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt: A 5.6-year prospective study. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(2), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2141

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1124, 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1440.010

Croarkin, P. E., Nakonezny, P. A., Deng, Z. D., Romanowicz, M., Voort, J. L. V., Camsari, D. D., Schak, K. M., Port, J. D., & Lewis, C. P. (2018). High-frequency repetitive TMS for suicidal ideation in adolescents with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 282–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.048

Cullen, K. R., Amatya, P., Roback, M. G., Albott, C. S., Westlund Schreiner, M., Ren, Y., Eberly, L. E., Carstedt, P., Samikoglu, A., Gunlicks-Stoessel, M., Reigstad, K., Horek, N., Tye, S., Lim, K. O., & Klimes-Dougan, B. (2018). Intravenous ketamine for adolescents with treatment-resistant depression: An open-label study. Journal of Child Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 28(7), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2018.0030

Gibbons, R. D., Brown, C. H., Hur, K., Marcus, S. M., Bhaumik, D. K., Erkens, J. A., Herings, R. M., & Mann, J. J. (2007). Early evidence on the effects of regulators’ suicidality warnings on SSRI prescriptions and suicide in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(9), 1356–1363. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030454

Gogtay, N., Giedd, J. N., Lusk, L., Hayashi, K. M., Greenstein, D., Vaituzis, A. C., Nugent, T. F., 3rd, Herman, D. H., Clasen, L. S., Toga, A. W., Rapoport, J. L., & Thompson, P. M. (2004). Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101(21), 8174–8179. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0402680101

Hafeman, D. M., Rooks, B., Merranko, J., Liao, F., Gill, M. K., Goldstein, T. R., Diler, R., Ryan, N., Goldstein, B. I., Axelson, D. A., Strober, M., Keller, M., Hunt, J., Hower, H., Weinstock, L. M., Yen, S., & Birmaher, B. (2020). Lithium versus other mood-stabilizing medications in a longitudinal study of youth diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(10), 1146–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.06.013

Hammad, T. A., Laughren, T., & Racoosin, J. (2006). Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(3), 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.332

Hammerslag, L. R., & Gulley, J. M. (2016). Sex differences in behavior and neural development and their role in adolescent vulnerability to substance use. Behavioural Brain Research, 298(Pt A), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2015.04.008

Harms, M. B., Casement, M. D., Teoh, J. Y., Ruiz, S., Scott, H., Wedan, R., & Quevedo, K. (2019). Adolescent suicide attempts and ideation are linked to brain function during peer interactions. Psychiatry Research Neuroimaging, 289, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2019.05.001

Johnston, J. A. Y., Wang, F., Liu, J., Blond, B. N., Wallace, A., Liu, J., Spencer, L., Cox Lippard, E. T., Purves, K. L., Landeros-Weisenberger, A., Hermes, E., Pittman, B., Zhang, S., King, R., Martin, A., Oquendo, M. A., & Blumberg, H. P. (2017). Multimodal neuroimaging of frontolimbic structure and function associated with suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults with bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174(7), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15050652

Kalb, L. G., Stapp, E. K., Ballard, E. D., Holingue, C., Keefer, A., & Riley, A. (2019). Trends in psychiatric emergency department visits among youth and young adults in the US. Pediatrics, 143(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2192

Kendler, K. S., Ohlsson, H., Sundquist, J., Sundquist, K., & Edwards, A. C. (2020). The sources of parent-child transmission of risk for suicide attempt and deaths by suicide in Swedish national samples. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(10), 928–935. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20010017

Lu, C. Y., Zhang, F., Lakoma, M. D., Madden, J. M., Rusinak, D., Penfold, R. B., Simon, G., Ahmedani, B. K., Clarke, G., Hunkeler, E. M., Waitzfelder, B., Owen-Smith, A., Raebel, M. A., Rossom, R., Coleman, K. J., Copeland, L. A., & Soumerai, S. B. (2014). Changes in antidepressant use by young people and suicidal behavior after FDA warnings and media coverage: Quasi-experimental study. British Medical Journal, 348, g3596. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3596

Nock, M. K., Park, J. M., Finn, C. T., Deliberto, T. L., Dour, H. J., & Banaji, M. R. (2010). Measuring the suicidal mind: Implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychological Science, 21(4), 511–517. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610364762

Posner, K., Oquendo, M. A., Gould, M., Stanley, B., & Davies, M. (2007). Columbia classification algorithm of suicide assessment (C-CASA): Classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(7), 1035–1043. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1035

Shiffman, S., Stone, A. A., & Hufford, M. R. (2008). Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415

Wilcox, H. C., Fullerton, J. M., Glowinski, A. L., Benke, K., Kamali, M., Hulvershorn, L. A., Stapp, E. K., Edenberg, H. J., Roberts, G. M. P., Ghaziuddin, N., Fisher, C., Brucksch, C., Frankland, A., Toma, C., Shaw, A. D., Kastelic, E., Miller, L., McInnis, M. G., Mitchell, P. B., & Nurnberger, J. I., Jr. (2017). Traumatic stress interacts with bipolar disorder genetic risk to increase risk for suicide attempts. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(12), 1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.09.428

Zimmerman, M., Clark, H. L., Multach, M. D., Walsh, E., Rosenstein, L. K., & Gazarian, D. (2015). Have treatment studies of depression become even less generalizable? A review of the inclusion and exclusion criteria used in placebo-controlled antidepressant efficacy trials published during the past 20 years. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(9), 1180–1186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.06.016

Funding Details

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH (Annual Report Numbers ZIAMH002922 and ZIAMH002927).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ballard, E.D., Pao, M. (2022). Neurobiology of Suicide in Children and Adolescents: Implications for Assessment and Treatment. In: Ackerman, J.P., Horowitz, L.M. (eds) Youth Suicide Prevention and Intervention. SpringerBriefs in Psychology(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06127-1_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06127-1_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-06126-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-06127-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)