Abstract

This chapter studies the exchanges of ideas and experiences related to public information within the Nordic region and beyond. As an empirical case, the analytical focus centres on the Swedish Board of Public Information (Nämnden för samhällsinformation, 1971–1981) and traces the various contacts—through seminars, study visits, conferences, and so on—that the agency initiated and was part of during the 1970s. By examining the archival material through the concepts of epistemic community and circulation of knowledge, the analysis shows how issues of public information attracted various actors—which represented different social sectors (bureaucracy, advertising industry, academia, etc.) and different interests—that met across national borders in attempts to address challenges of communicating societal important information to citizens.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Public information

- Epistemic community

- Board for Civic Information

- Circulation of knowledge

- Governmental information

The 1970s was a decade of information debates. Often, UNESCO’s biannual General Conference in Nairobi 1976 is used as a symbol by scholars to exemplify these intense discussions. At that meeting, delegates from the global south advocated for redistributed flows of information and for enhanced national control over broadcasting and newspaper media—a new world order of information.Footnote 1 Other discussions have not received the same scholarly attention. In parallel with the UNESCO meeting, for example, another conference took place in Oslo in Norway. Here, delegates from the Nordic countries gathered to discuss other kinds of information flows, those between public agencies and citizens, so-called public information. Based on the archived minutes of the Oslo meeting, no such intense debates seemed to have occurred as the ones that took place in Nairobi, and the topic and circumstances were of course different. Still, the Nordic participants considered issues of public information urgent, connected to contemporary and future societal challenges and problems.Footnote 2 Moreover, they were regarded as issues with shared features and challenges that needed to be discussed in a transnational community. Focusing on a specific Swedish agency—the Board for Civic InformationFootnote 3 (Nämnden för samhällsinformation)—this chapter examines how Nordic and international actors exchanged experiences and ideas of public information during the 1970s.

There were several contextual similarities among the Nordic countries related to issues of public information in the 1960s and the 1970s. The heightened attention to how the state should communicate laws and recommendations to its citizens, for example, was fuelled by the increased complexity of an expanding public sector, demands for a strengthening of citizens’ capacity to participate in societal processes, and a changing media landscape. These shared conditions make the Nordic region an interesting case to study how experiences and ideas of public information travelled and were discussed.

This chapter treats public information as an information policy-related problem and at the same time a cross-border problem shared by different countries. Three research questions are posed: Which kinds of experiences and ideas related to public information travelled across the Nordic countries, and in which forums where they discussed? What interests were represented when actors met from different countries? Can we discern an ambition to form a Nordic Model for public information? By analytically approaching this study from a transnational standpoint, it is possible to examine problems and opportunities connected to public information that were shared among stakeholders from different countries, and how these actors could have a potential influence on national policies.

This chapter uses the term “public information”.Footnote 4 This term signals a broader notion than strictly dissemination of information about laws and regulations from state agencies to citizens, so-called governmental information. Public information, in turn, should here be understood as governmental information and other kinds of information that are thought of as important from a societal point of view and delivered by society-oriented organizations and industries, for instance trade unions and state-owned companies. Hence, such information could broadly relate to various aspects that citizens would need to navigate in society, such as workers’ rights and consumer information.Footnote 5 Theoretically, epistemic community and circulation of knowledge are used to unpack public information as a transnational issue in the Nordic region during the 1970s.

Empirically, the chapter foregrounds the Swedish Board for Civic Information, active between 1971 and 1981, and traces its contacts outside the national context. The analysis reconstructs the Board’s international contacts and exchanges through its archived correspondence series. Hence, the representation of countries is empirically defined. Consequently, this has generated an analysis that emphasizes Norwegian and Danish exchanges, some Finnish ones, no Islandic connections, and a few exchanges with countries outside the Nordic region. Due to the principle of public access to government files in Sweden, most meetings of this kind should have resulted in written, and later filed, correspondence between the Swedish and the foreign party. The archived accounts of these meetings—study visits, seminars, and workshops—are unfortunately often scarce in details, especially when it comes to thorough meeting minutes. Only some conferences have left a more detailed documentation. Still, the material provides a solid base to approach the chapter’s research questions.

Research on public information tends to focus on contemporary and best practice-oriented issues.Footnote 6 Scholarly works on its historical developments—especially relating to the 1970s—are scarcer, and those that exist tend to focus on specific countries. Within a Nordic context, and except for some scattered articles and book chapters, there are only a few notable contributions. Fredrik Norén’s PhD thesis, for example, on the formation of governmental information in Sweden between 1965 and 1975, and Jesper Vestermark Køber’s PhD thesis on the concept of local democracy in Denmark in the 1970s, which also touches upon public information policies.Footnote 7 Hence, this chapter contributes to this research body by examining public information as a transnational and Nordic issue during the 1970s.

Epistemic Community and Circulation of Knowledge

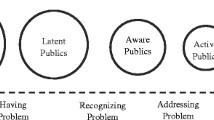

Scholars of information science tend to argue that the field of information policy is characterized by porous boundaries to other related policy fields such as education, security, and health. One reason for this is the ambiguous notion of information, which can allude to different things in various contexts. Consequently, information policy issues have the potential to attract stakeholders from different societal sectors, representing different interests.Footnote 8 These conditions make it relevant to also understand the formation of public information policies in relation to the framework of epistemic community.

Epistemic community is a concept developed by political scientist Peter M. Haas to understand how the complexity and uncertainty of a policy issue, often shared between countries or regions, are addressed. Haas defines such communities as “a network of professionals with recognized expertise and competence in a particular domain and an authoritative claim to policy-relevant knowledge within that domain or issue-area”.Footnote 9 An epistemic community can consist of different governmental and non-governmental professional actors. Together, they embody a shared worldview deriving from a common set of normative and causal beliefs, as well as shared knowledge, notion of validity, and a joint policy mission for which the actors produce relevant knowledge.Footnote 10 In particular, issues that comprise complexity and uncertainty—for example, the principles for and organizational forms of public information in the 1970s—tend to stimulate demands for knowledge exchanges. Steeped in interpretations, such knowledge is a social construct, generated from interacting actors. Ultimately, these communities have the potential to provide knowledge to, and impact, national policy makers.Footnote 11

This chapter will demonstrate how, as an ambiguous and complex issue, public information has the potential to generate an epistemic community of related professionals. And furthermore, that such a community is an arena where knowledge, decisions, and initiatives are steeped in discussions and negotiations at the intersection between various actors and interests. Here, circulation of knowledge constitutes a second perspective to understand the formation processes of public information in the Nordic region.Footnote 12 The perspective can be fruitful to employ when studying how this issue was configured, and reconfigured, by different layers of practically and theoretically oriented ideas and experiences from different societal spheres.Footnote 13 Researchers who study processes of knowledge circulation tend to focus on how ideas, actors, and content, among other things, travelled and were exposed to different arenas and historically situated communities, which might influence these ideas, actors, and content in new directions. However, researchers can also put an emphasis on how such circulation, in turn, creates new forums for exchange and interactions. How letter correspondence, for example, leads to physical meetings, and in turn to deeper collaboration.Footnote 14 In this chapter, the analysis focuses on various Nordic and international exchanges that the Swedish Board for Civic Information took part in during the 1970s. More specifically, it studies different kinds of ideas and experiences connected to public information that were circulated and shared in forums that resemble an epistemic community.

Public Information in the 1960s and 1970s

States have always been keen on using information as a tool to govern. The forms and usages have changed through history depending on societal contexts and dominating communication systems.Footnote 15 The breakthrough of democracy, for example, saw gradually increased demands for the use of information as a deliberative tool for citizens, partly to create a more equal relationship between the authorities and the people.Footnote 16 This was also true for the 1960s and the 1970s. During this period, the Nordic region—as well as other western countries—saw renewed attention to challenges and problems connected to public information that needed to be addressed.

After World War II, information-related issues started to rise up the political agenda in several western countries. Media historian Brendan Maartens has, for example, described the British period after 1945 as follows: “just as ‘imperialism’ and ‘empire’ had been central to discussions of the British state in 1895–1914, ‘information’ became part and parcel of political discourse in the post-war era”.Footnote 17 The notion of information became increasingly integrated in shifting academic disciplines as an important variable to understand and explain society and the human condition, as well as a means to solve societal problems.Footnote 18 During the 1970s, information also became associated with internationally and politically sensitive discussions, later often symbolized by the UNESCO debate about the so-called new world information and communication order, mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. In fact, as argued by media and communication scholar Ulla Carlsson, “never—neither before nor since—have information flows been debated with such passion as in the 1970s”.Footnote 19 To some extent, the attention to information flows also applies to different national contexts.

The expansion of the state in the post-war era, be it welfare states or not, caused a growing complexity of the societal structure, which in turn created increased demands for an informed citizenry.Footnote 20 As social reforms brought about new legislation, citizens needed to be informed if these reforms were to be efficiently implemented.Footnote 21 Moreover, as the democratic bureaucracy grew, so did the body of governmental documents, which also raised the question of transparency. Hence, during the 1960s and 1970s, several countries directed their attention to information-associated legislation, often related to access to public documents.

Internationally, one of the more famous information laws during this period was the Freedom of Information Act in the United States in 1966, which spread interest in and spurred debates on similar laws in other western countries, for instance in West Germany.Footnote 22 In the Nordic region, similar legislation for public access to governmental files was implemented in Denmark in 1970, Finland in 1950, Norway in 1970, and Iceland in 1996 (although there were differences in the implementations). Sweden stands out as the first in the world to implement legislation on access to governmental documents, dating back to 1766.Footnote 23 However, during this time, the debates on information policies were not limited to accessing public information but also related to the right of citizens to be actively provided with information by state authorities.Footnote 24

The 1960s and especially the 1970s are often described as an active and expansive decade for public information in the Nordic region.Footnote 25 In fact, already in 1987, Danish governmental information investigator Lars Nordskov Nielsen described the era as the “classic paradigm” of public information policies.Footnote 26 The expansion of, and increased interest in, public information can be understood in the light of at least three broad and to some extent coinciding societal developments. Firstly, the expansion, centralization, and increased complexity of the welfare state created a need for more information to citizens, as well as a demand for a decentralized state to address the growing divide between the citizens and the political-bureaucratic apparatus. Secondly, the radicalization of society during the 1960s and 1970s made governments address growing citizen demands for increased influence in societal processes. Here, information was perceived as an important instrument for a deepened democracy. The evolving media landscape, which was then perceived to be in a time marked by significant changes, can be characterized as a third process in the formation of public information policies in the Nordic region and elsewhere, for example connected to various media-related legislation, changing patterns of media consumption, and the formation of media studies.Footnote 27

In the Nordic region, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden also had a similar development towards at least partly centralized public information policies, leading to a specific state agency mandated to support other authorities with their external information issues. Although the Danish National Advertising Bureau (Statens annonce- og reklamebureau) was established already in 1937, it was not until 1975—when the agency changed its name to the Danish Information Office (Statens informationskontor)—that its assignments expanded, partly to include co-production of TV spots containing public information from Danish state agencies.Footnote 28 In the late 1950s, a Norwegian debate on governmental advertisement in the press was instrumental in forcing the Norwegian government in 1960 to appoint a committee of inquiry to scrutinize the state’s external information activities towards the citizens.Footnote 29 As a result, and based on the committee’s recommendation, the Norwegian Information Service (Statens informasjonstjeneste) was established in 1965.Footnote 30 This new state agency was assigned with the task of acting as a consultant to ministers and other state authorities in information-related issues, and to some extent helping to plan and implement information campaigns.Footnote 31 A couple of years later, in 1967, the Swedish government in turn appointed the Commission on Public Information, which came to similar conclusions as its Norwegian counterpart.Footnote 32 This prompted the government in 1971 to establish the Swedish Board for Civic Information, assigned with the main task of coordinating state agencies’ public information activities and providing them with consultative help.Footnote 33 From 1972, Sweden also aired TV spots from state agencies, a system that Denmark later adopted. However, the Swedish Board had less to do with this system, which instead was a collaboration between individual authorities and Swedish Radio, the national broadcasting company.Footnote 34

To conclude, the developments that preceded the different information agencies in the Nordic countries could, on a general level, be regarded as similar.Footnote 35 As could the critical opinions against the state authorities’ communication strategies, which were built on comparable ideas such as criticism towards one-way information, manipulation, and outdated communication techniques.Footnote 36 Moreover, during the post-war era, the Nordic countries launched various information and media-oriented and cross-border projects, for example related to radio, television, satellite and telecommunication.Footnote 37 Such conditions are likely to have strengthened the will to reach out in order to learn and share experiences across the Nordic countries.

The Swedish Board for Civic Information and Its Transnational Forums

In 1971, the Swedish government issued the newly established Board for Civic Information with instructions to guide the agency’s work. These included surveying, investigating, and coordinating state agencies’ external information activities, as well as supporting agencies with recommendations, consultation, and education related to this area.Footnote 38 Organizationally, the agency was divided into a politically appointed steering board, and an office with employed officials responsible for implementing the government’s instructions. Initially, the office had five full-time employees its director Bernt Björck—but would soon expand to nine officials,Footnote 39 and a couple of years before its disestablishment in 1981, the office had increased to 14 employees.Footnote 40

Up until 1975, the Board for Civic Information only had a few filed correspondence and exchanges with actors outside Sweden (see Fig. 1). Nevertheless, even these early activities—including official James Brade’s participation in the Helsinki seminar “An afternoon on public information” (arranged by the European Association of Advertising Agencies and the Finnish Association of Advertising Agencies), and Björck’s 1973 seminar visit to Bergen along with participants from Norwegian advertising agencies—give an indication of the Swedish Board’s interest in the advertising industry.Footnote 41 This interest was mutual, since advertising agencies seemed attentive to official public information activities. After the Bergen seminar in 1973, for instance, a representative from the well-known Swedish advertising firm Ervaco wrote to Björck and described the director’s talk about the Board’s work in terms of “respect and admiration”.Footnote 42

Later, during the second half of the 1970s, the Board’s Nordic and international contacts and exchanges intensified. Beyond correspondence by letter, these took place in three types of forums: study visits, seminars and workshops, and conferences, of which study visits were the most common forum. In retrospect, the agency viewed such contacts as important to “study the development in other countries and take part in experiences from others who have been in a similar or the same situation”.Footnote 43 Furthermore, when representatives from Nordic countries met on different occasions and discussed public information-related issues, they often recognized a joint set of “problems and attitudes”—as a participant at the 1976 Oslo conference on public information expressed it—despite some differences in, for instance, organizational solutions.Footnote 44 These contact forums resemble Haas’ description of how a transnational epistemic community is formed by actors from different countries to address the uncertainty and complexity of a specific issue. In such forums, participating actors’ notions of challenges and solutions about a specific issue are circulated and interpreted.Footnote 45

Analysing the Board’s archived correspondence series, it becomes clear that the different meetings between the Nordic countries centred around some recurring themes that represent the uncertainty and complexity of public information. On the one hand, information was perceived as a tool to solve problems in society and, on the other hand, as something that created societal problems, which in turn needed to be addressed with additional information policies—for example issues related to information divides. These themes can be summarized in five, to some extent overlapping, categories connected to (1) effects and evaluation of disseminated information; (2) information divides in society; (3) demand for more or better information; (4) techniques, methods, and best practices; and (5) organizational issues of public information.

The five categories above can be understood as pressing issues that different countries shared an interest in dealing with. Furthermore, and relating to the concept of epistemic community, these matters attracted professional representatives from Nordic countries to discuss their related experiences and challenges on the topic. These were not arenas for competing and negotiating actors, but rather forums to discuss and find practically oriented (epistemic) solutions to various perceived problems that needed to be solved. In September 1976, as a typical example, a delegation from the Norwegian Information Service conducted a study visit to Stockholm, coordinated by the Board for Civic Information, to learn about how “Sweden has solved—or wants to solve—a number of questions related to public information”. These questions concerned, for instance, information practices at the municipality level, immigrant information, and contacts between Swedish broadcasting and public authorities. During the stay, the delegation visited representatives from, among others, the Swedish Educational Broadcasting Company (Utbildningsradion), the Swedish Immigration Agency (Statens invandrarverk), and Södertälje Municipality.Footnote 46 Similar study visits from Norway and Denmark were also conducted during the latter half of the 1970s, with representatives from the bureaucracy, advertising industry, academia, and journalism.Footnote 47

At the Nordic meetings, practically oriented discussions on public information dominated. This was, for example, the case when the Swedish Board visited other countries outside the Nordic region, such as the international “Public Service Advertising Conference” arranged by the International Advertising Association (IAA) in Brussels in 1979, which gathered some 350 participants from all over the world. The purpose of the conference was indeed practically oriented: “to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas and information concerning the creation, development and implementation of public service advertising campaigns.”Footnote 48

Still, some exceptions regarding more theoretical and philosophical discussions are also notable in the archive material. One such example was at the “Research in Public Information” conference in Gothenburg in 1981, where a panel discussed the conceptualizations of society and the citizen in relation to public information.Footnote 49 This panel gathered academics from different disciplines—Göte Hanson from psychology, Jörgen Westerståhl from political science, Preben Sepstrup from market economics, to mention a few—as well as official representatives from Nordic municipalities and state agencies. Another example was the Nordic Media-Forsk conference in 1975 (today the NordMedia conference), which took place in Denmark. One of the conference’s working groups was dedicated to “public information and information divides”—chaired by Swedish media and communication scholar Kjell Nowak and Dan Lundberg—and gathered researchers and officials, for example James Brade from the Board for Civic Information, to discuss different theoretical communication models and how to prevent inequalities related to public information.Footnote 50

The overall focus on practically oriented discussions can partly be linked to the influence that social sciences had on media and information policies, as well as on the formation of media studies at that time—in Sweden as well as in other countries.Footnote 51 Still, it should be mentioned that the so-called behavioural research ideal was continuously confronted by loudly critical left-wing opinion. Instead of focusing on how best to create information with desirable effects and feedback loops of various kind, the opposing voices often emphasized the need for mutual dialogue between bureaucracy and citizens, and to use information as a way to enhance citizen participation in society. These voices were, however, more heard in the public debateFootnote 52 and rarely entered the arenas where the Board discussed public information outside Sweden. When critically oriented perspectives were discussed, it was often in contexts where researchers participated, as in the example from the two conferences above.

The examples above indicate that the Swedish Board for Civic Information was drawn to and became involved in forming an epistemic community of certain perspectives, ideas, and experiences related to public information. “Members of an epistemic community tend to pursue activities that closely reflect the community’s principled beliefs and tend to affiliate and identify themselves with groups that likewise reflect or seek to promote these beliefs”, as Peter M. Haas describes it.Footnote 53 This community, in turn, made it more difficult, and perhaps less attractive, for critically oriented actors, such as researchers, to participate in the discussions.

Public Information in the Intersection Between Different Sectors and Interests

One would suspect that policies for public information were a concern for selected groups of bureaucrats and policy makers. However, tracing the paths of the historical actors, the archived correspondence material from the Swedish Board for Civic Information shows that different actors from academia, the advertising industry, bureaucracy, news media, and political parties initiated meetings and were represented at study visits, seminars, and conferences, at which experiences and ideas of public information were exchanged and discussed. In fact, it is fascinating how seemingly naturally stakeholders from different sectors during this era reached out, met, and interacted.

Study visits were a common exchange activity and had different initiators, such as advertising companies, state agencies, universities, and broadcasting institutions. In June 1975, for example, the advertising company Ervaco arranged a study visit in Sweden, coordinated by its branches in Oslo and Stockholm. For three days the delegates—including staff from the Norwegian Information Service—met and talked to information officers from Swedish state agencies, municipalities, and trade unions, as well as the principal of the Institute for Communication and Advertising Education, and took part in a concluding panel discussion led by Bernt Björck, the director of the Board for Civic Information.Footnote 54 Two years later, Ervaco re-visited Stockholm, where about 60 people met to discuss issues of public information (Fig. 2).Footnote 55

In 1977, the advertising company Ervaco’s Norwegian branch organized a study visit to Stockholm. Forty people from Norway and twenty from Sweden, representing different interests and societal sectors, met during three days and discussed issues of public information. This is the front page of the study visit programme. From National Archive of Sweden, Board for Civic Information, E1A:66

Another example includes a study visit to the Swedish Board by a group of students from the media programme at Volda University College in Norway. It took place in 1975, and like Ervaco’s study visits, this seems to have been appreciated by the student group, since it was followed up by a similar tour the next year. Based on the wishes of the Volda coordinator, the Board also arranged an activity programme that, among others, included meetings with representatives from the Stockholm School of Journalism, the Swedish Educational Broadcasting Company, Liber (a publisher of educational material), as well as information officials from state and municipality agencies.Footnote 56

Furthermore, the Board for Civic Information went on its own study visits, both to Nordic countries—such as various visits to the Norwegian Information Service—and outside the region.Footnote 57 Regarding the latter, the Board, together with representatives from other Swedish state agencies, went on an ambitious five-day visit to the UK in 1980 (Fig. 3). There, the 16 delegates met with representatives from the Central Office of Information’s advertising division, the Department of Social Services, Greater London Council’s public relations branch, an advertising agency (used in “government information campaigns”), the Post Office, and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). At the BBC, the delegation discussed, among other things, issues related to “dissemination of public information material” over the radio. Some of the BBC’s “TV spots” were also shown to the delegation, who also received a cassette with copies of these short films, which were later shown and discussed back home in Sweden.Footnote 58 Other countries outside the Nordic region that the Swedish Board visited during the period were France and West Germany.Footnote 59

These intersecting meetings between different societal sectors show that various interests, perspectives, and agendas were made known to each other. Public information could hence be understood as a form of knowledge that evolved through circulation between actors from different countries, and related to commercial, academic, and administrative interests.Footnote 60 This observation is also aligned with Haas’ view that these community meetings could be interpreted as “channels through which new ideas circulate from societies to governments as well as from country to country” and that these ideas were carried by actors who function as both “cognitive baggage handlers as well as gatekeepers governing the entry of new ideas into institutions”.Footnote 61

Besides advertising and broadcasting companies, the Swedish Board for Civic Information also had established connections with academic institutions in Sweden and abroad. Sverker Thorslund was one such key figure, an employed official at the Board with a licentiate degree from Stockholm School of Economics Institute for Research. Among other activities, he took part in the previously mentioned Nordic media and communication conference Media-Forsk, where he participated in the working group “The Local Communication System”. Thorslund also gathered knowledge related to public information from different intuitions—UNESCO, UC Berkeley, the Australian Embassy, and so on—and was present when a delegation from the Government of Quebec’s Department of Communication visited Stockholm in 1975.Footnote 62

Furthermore, the Board for Civic Information was involved in various activities in which researchers participated. Besides the previously mentioned conferences, other such meetings included different seminars on public information. One such seminar was held in Oslo, arranged by the Norwegian Information Service, at which Stein Bråten—then professor of sociology—talked about communication issues.Footnote 63 The presence of researchers in these meetings can partly be understood as a way of positioning themselves and pushing the perspectives they represented—such as behavioural science approaches or critical theory perspectives—in relation to the policy-oriented actors such as the staff at the Board for Civic Information.

The different meetings reveal a developed network, with a low boundary and little friction between bureaucracy, industry, and academia when it came to establishing contacts and performing knowledge exchange. As ideas and experiences about public information were exposed in the intersection between different interests and sectors, this circulation of knowledge resembles the formation processes of media studies, at least in Sweden, which occurred at similar crossings. It should be said, though, that it is difficult to discern specific and concrete effects of these meetings on the participating organizations’ work and activities related to public information. However, the fact that different representatives from the Nordic countries continued to meet, indicates a will to learn and adapt—and to promote one’s own work and ideas.Footnote 64

A Nordic Model for Public Information? Towards Some Concluding Remarks

Is it reasonable to argue that a Nordic Model for public information was consolidated, or at least considered possible, during the 1970s? Issues of public information attracted actors from different countries and societal sectors to seek contact and meet, partly due to shared notions of problems and solutions. As has been argued in this chapter, this resembles an epistemic community with a shared worldview and an agenda to address the complexity surrounding the issues of public information. At these transnational forums, ideas and practically oriented knowledge about public information were gladly exchanged. However, it is difficult to trace and measure how much of the collaborative potential between the Nordic countries was realized. This applies in particular to long-term policy change, which is something beyond the scope of this chapter.

Analysing the empirical material from a transnational approach, and applying perspectives of epistemic community and circulation of knowledge, one could, however, discern some concluding observations. And despite difficulties in tracing how knowledge and policies of public information were affected by the transnational exchanges in specific ways, it is possible to point to a few areas where at least Denmark, Norway and Sweden went in a similar direction. Comparable organizational infrastructure, for instance, with centralized state agencies for public information, was established (and re-organized in Denmark) in the 1960s and the 1970s.

The interest in public information-related issues was, of course, not unique for the Nordic countries during the 1970s, and the Swedish Board’s transnational contacts also extended to other western countries. Public information policies, often emphasizing access to public documents and public information, were legislated and implemented in several countries during the 1960s and 1970s. In the Nordic region, another focus also existed: how authorities actively could and should disseminate information to citizens. Here, as mentioned previously in this chapter, the problems and challenges of public information were often similar, for example related to practically oriented issues such as how to reach different groups of citizens with information, which media were more effective, and how to evaluate information campaigns.

Examples also exist of how the Nordic countries were inspired by each other. One example is the system of short TV spots financed and produced by state agencies. Such a concept was implemented in Sweden in 1972, with spots aired on public service television (which at that time held a TV monopoly, with only two existing channels). The Swedish model was based on a recommendation from the same government commission of inquiry, the Commission on Public Information, that proposed the establishment of the Board for Civic Information.Footnote 65 The idea of state-financed TV programmes was controversial since it could, as the critiques argued, jeopardize the role of an independent public service.Footnote 66 Nonetheless, in the late 1970s, the Swedish system was adopted by Denmark.Footnote 67

Differences in legislation were a natural barrier when it came to a joint Nordic Model for public information. Norwegian public service legislation, for instance, made it difficult to adopt a TV spot system like the one implemented in Denmark and Sweden. This and other obstacles were a topic discussed at the Nordic conference on public information in Oslo 1976, mentioned in the introduction to this chapter.Footnote 68 Still, at the various meetings where representatives from the Nordic countries met to discuss issues of public information, it is evident that participants showed a generally positive attitude towards collaborations within the Nordic region. Differences between the countries were recognized, but did not prevent a will to collaborate, for example related to “information approaches in the social sector, environmental protection, transport, opinion polls and testing of information materials”, as a participant pointed out at the 1976 conference in Oslo.Footnote 69 Three years later, another Nordic conference on public information was arranged in Copenhagen in order to deepen the contacts within the region. Once again it was concluded that they—at least Denmark, Norway and Sweden—shared the same problems and challenges related to issues of public information. Furthermore, it was agreed that “the form of exchange of experience between the Nordic countries must be established”, and that the different Nordic state agencies for public information should meet at least once a year.Footnote 70 However, since the Swedish Board for Civic Information was dismantled in 1981, it is unlikely that the Nordic collaboration got as firm a structure as was intended.

To conclude, a move towards a joint model for Nordic public information in the 1970s seems less reasonable. However, this chapter reveals that issues of public information should not exclusively be understood as isolated concerns for each country. Yes, specific political issues that citizens needed to be informed about were often framed within national contexts, but ideas, experiences, and organizational structures of public information—broad aspects that in the end tend to affect policies—were not. These complex issues attracted people across borders to discuss, share knowledge, promote ideas, and learn from each other.

Notes

- 1.

Courier, no. 4 (1977); Ulla Carlsson, “The Rise and Fall of NWICO: From a Vision of International Regulation to a Reality of Multilevel Governance”, Nordicom Review, no. 2 (2002).

- 2.

“Referat fra utvalgets 10. Møte mandag den 15. November 1976”, E1A:50, Nämnden för samhällsinformation (Board for Civic Information, BCI), Riksarkivet (National Archive of Sweden in Marieberg, NAS), hereafter BCI:NAS.

- 3.

The English translation of the name is the agency’s own. See for example, “The National Board for Civic Information: Its Background, Organization and Duties”, E1A:20, BCI:NAS.

- 4.

A direct translation would be “offentlig information” (in both Swedish and Danish, and in Norwegian “offentlig informasjon”). However, the Swedish term “samhällsinformation” (societal information) is a more historically adequate translation for the 1970s (“samfundsinformation” in Danish, and “samfundsinformasjon” in Norwegian). The nomenclature, however, was not stable, and different terms were used simultaneously. For example, the Board used “civic information” when it described itself in international contexts.

- 5.

See discussion in Fredrik Norén, “Deliberation or Manipulation? The Issue of Governmental Information in Sweden, 1969–1973”, Information & Culture, vol. 55, no. 2 (2020).

- 6.

For example Peter John, “All Tools Are Informational Now: How Information and Persuasion Define the Tools of Government”, Policy and Politics, vol. 41, no. 4 (2013); Nazareth Echart and Maria Jose Canel, “The Role and Functions of Government Public Relations: Lessons from Public Perceptions of Government”, Central European Journal of Communication, vol. 4, no. 1 (2011); Jennie M. Burroughs, “What Users Want: Assessing Government Information Preferences to Drive Information Services”, Government Information Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 1 (2009).

- 7.

Fredrik Norén, “Framtiden tillhör informatörerna”: Samhällsinformationens formering i Sverige 1965–1975 (Umeå: Umeå universitet, 2019); Jesper Vestermark Køber, Et spørgsmål om nærhed: Nærdemokratibegrebets historie i 1970’ernes Danmark (Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 2017).

- 8.

Mairéad Browne, “The Field of Information Policy: 1. Fundamental Concepts”, Journal of Information Science, vol. 23, no. 4 (1997); Ian Rowlands, “Information Policy”, International Encyclopedia of Information and Library Science, eds. J. Feather and P. Sturges (London: Routledge, 2003).

- 9.

Peter M. Haas, “Introduction: Epistemic Communities and International Policy Coordination”, International Organization, vol. 46, no. 1 (1992): 3.

- 10.

Mai’a K. Davis Cross, “Rethinking Epistemic Communities Twenty Years Later”, Review of International Studies, vol. 39, no. 1 (2013); Claire A. Dunlop, “Epistemic Communities”, Routledge Handbook of Public Policy, eds. Eduardo Araral Jr., Scott Fritzen, Michael Howlett, M. Ramesh and Xun Wu (London: Routledge, 2013).

- 11.

Haas, “Introduction”.

- 12.

Johan Östling, David Larsson Heidenblad, Erling Sandmo, Anna Nilsson Hammar and Kari H. Nordberg, “The History of Knowledge and the Circulation of Knowledge: An Introduction”, Circulation of Knowledge Explorations in the History of Knowledge, eds. Johan Östling, David Larsson Heidenblad, Erling Sandmo, Anna Nilsson Hammar and Kari H. Nordberg (Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2018).

- 13.

Cf. Peter Burke, What is History of Knowledge? (Cambridge: Polity, 2015), 89–91.

- 14.

Östling et al., “The History of Knowledge and the Circulation of Knowledge”.

- 15.

For example, Robert Darnton, “An Early Information Society: News and the Media in Eighteenth-Century Paris”, The American Historical Review, vol. 105, no. 1 (2000); Burke, What is History of Knowledge?, 100–102.

- 16.

Edward Higgs, The Information State in England: The Central Collection of Information on Citizens Since 1500 (London: Palgrave, 2004): 149–157; Mordecai Lee, “An Overview of Public Reporting”, Government Public Relations: A Reader, ed. Mordecai Lee (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2008), 144–148.

- 17.

Brendan Maartens, “From Propaganda to ‘Information’: Reforming Government Communications in Britain”, Contemporary British History, vol. 30, no. 4 (2016), 3.

- 18.

César A. Hidalgo, Why Information Grows: The Evolution of Order, from Atoms to Economies (New York: Basic Books, 2015), xiv–xv.

- 19.

Carlsson, “The Rise and Fall of NWICO”, 31.

- 20.

For example, Higgs, The Information State in England, 149–157.

- 21.

Mordecai Lee, “Introduction to section V”, Government Public Relations: A Reader, ed. Mordecai Lee (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2008), 255–257; Russell L. Weaver, “Governmental Transparency and Openness in a Digital Era: Transparency, Privacy, and Democracy”, Transparency in the Future: Swedish Openness 250 Years, eds. Anna-Sara Lind, Jane Reichel & Inger Österdahl (Visby: Ragulka press, 2017), 159–160.

- 22.

Browne, “The Field of Information Policy”; Cornelia Vismann, Lagen och arkivet: Akternas mediehistoria (Gothenburg: Glänta produktion, 2017), 280.

- 23.

Oluf Jørgensen, Access to Information in the Nordic Countries: A Comparison of the Laws of Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Norway and Iceland and International Rules (Gothenburg: Nordicom, 2014); Carsten Grønbech-Jensen, “The Scandinavian Tradition of Open Government and the European Union: Problems of Compatibility?”, Journal of European Public Policy, vol. 5, no. 1 (1998); Olav Hagen Sataslaatten, “The Norwegian Noark Model Requirements for EDRMS in the Context of Open Government and Access to Governmental Information”, Records Management Journal, vol. 24, no. 3 (2014).

- 24.

Norén, “Deliberation or Manipulation?”.

- 25.

For example, Arne Simonsen, “Staten vil deg vel, så gjør som den sier”: Offentlige kampanjer i 50 år (Oslo: Norsk kommunikasjonsforening, 2008), 7; Vestermark Køber, Et spørgsmål om nærhed: 170; Norén, “Framtiden tillhör informatörerna”, 37–51.

- 26.

Lars Nordskov Nielsen, Betænkning om offentlig information (Copenhagen: Administrationsdepartementet, 1987), 24.

- 27.

See, for example, Vestermark Køber, Et spørgsmål om nærhed; Norén, “Framtiden tillhör informatörerna”; Jostein Gripsrud, Allmenningen: Historien om norsk offentlighet (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2017), chapter 8; Henrik G. Bastiansen and Hans Fredrik Dahl, Norsk mediehistorie (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2008), 441–453.

- 28.

Betænkning 1967:469 Statens informationsvirksomhed; Betænkning 1977:787 Udvidet statslig information om love m. v. The co-production of TV spots was based on a similar model that was implemented in Sweden in 1972.

- 29.

Magne Lindholm, “Statens vennlige veileder: ‘Eriksenkampanjen’ i norske aviser 1956–1957”, Mediehistorisk tidsskrift, no. 27 (2017).

- 30.

Informasjonsutvalget, Statens informasjonstjeneste (Oslo: Finans- og tolldepartementet, 1962).

- 31.

NOU 1978:37 Offentlig informasjon.

- 32.

SOU 1969:48 Vidgad samhällsinformation.

- 33.

Norén, “Deliberation or Manipulation?”.

- 34.

Emil Stjernholm, “A Clash of Ideals: The Introduction of Televised Information in Sweden, 1969–1972”, Media History, vol. 28, 21 May 2022. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, a similar model was later implemented in Denmark.

- 35.

Compare Betænkning 1967:469; Betænkning 1977:787; Informasjonsutvalget, 1962; NOU 1978:37; SOU 1969:48.

- 36.

For example, Anker Brink Lund, “Statens informationsvirksomhed og dens politiske funktioner”, Politica, vol. 9, no. 2 (1977); Jan Ekecrantz, Makten och informationen (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 1975).

- 37.

Eli Skogerbø and Guttorm Aanes, “Europeisering av. det nordiske kultursamarbeidet”, Europa i Norden: Europeisering av nordisk samarbeid, eds. Johan P. Olsen & Bjørn Otto Sverdrup (Oslo: Tano Aschehoug, 1998).

- 38.

SFS 1971:509; Proposition 1971:56.

- 39.

“Nämnden för samhällsinformation 71/72 & 72/73”, 1973, E1A:13, BCI:NAS, 9.

- 40.

“Nämnden för samhällsinformation—En revisionsrapport”, 1977, E1A:68, BCI:NAS, 11.

- 41.

Letter, 9 February 1973, E1A:19, BCI:NAS; “Offentlig informasjon er en investering”, Bergens Tidning, 9 February 1973.

- 42.

Letter, 14 February 1973, E1A:19, BCI: NA.

- 43.

“Anhållan om medel för en studieresa till Norge för ledamöterna i nämnden för samhällsinformation”, 1980, E1A:89, BCI:NAS.

- 44.

For example, “Referat fra utvalgets 10. Møte mandag den 15. November 1976”, 1976, E1A:50, BCI:NAS, 17.

- 45.

Haas, “Introduction”, 17.

- 46.

Letter, 5 May 1976, E1A:50, BCI:NAS.

- 47.

For example, “Förteckning över informationssekreterare Trygve Tamburstuens studiebesök i Stockholm den 14 och 15 maj 1975”, E1A:34, BCI:NAS; “Nordisk seminar: studiereise i offentlig informasjonsvirksamhet: Stockholm 3–5 juni 75”, E1A:36, BCI:NAS; Letter, 10 November 1976, E1A:56, BCI:NAS; “Program”, 11 September 1980, E1A:94, BCI:NAS.

- 48.

Letter to Bernt Björck from A. Wolvesperges, 19 April 1979, E1A:85, BCI:NAS.

- 49.

NSI, Rapport om forskning och offentlig information: Nordisk konferens 13 och 14 januari 1981 Göteborg (København: Statens informationstjeneste; 1981), 57–58.

- 50.

Letter to conference participants, 16 May 1975, E1A:34, BCI:NAS; “Redogörelse för discussion i arbetsgruppen ‘informationsklyftor—samhällskommuikation’”, 25 August 1975, E1A:34, BCI:NAS.

- 51.

Mats Hyvönen, Pelle Snickars and Per Vesterlund, “The Formation of Swedish Media Studies, 1960–1980”, Media History, vol. 24, no. 1 (2018); Jefferson Pooley and David Park, “Introduction”, The History of Media and Communication Research: Contested Memories, eds. David Park and Jefferson Pooley (New York: Peter Lang, 2008), 1–15.

- 52.

For example, Norén, “Deliberation or Manipulation?”.

- 53.

Haas, “Introduction”, 19.

- 54.

“Nordisk seminar: Studiereise i offentlig informasjonsvikomhet”, E1A:36, BCI:NAS.

- 55.

Letters, programme, E1A:66, NSI:NA.

- 56.

“Förteckning över informationssekreterare Trygve Tamburstuens studiebesök i Stockholm den 14 och 15 maj 1975”, E1A:34, BCI:NAS; Letter, 9 May 1976, E1A:46, BCI:NAS.

- 57.

For example, “Förhandsinformation—studieresa till Norge”, 10 April 1980, E1A:89, BCI:NAS.

- 58.

Letters and programme, E1A:90, BCI:NAS. This was not the first visit to COI. In 1975, Göran Mandéus from the Board went to the UK to study how information was coordinated between different authorities, state agencies’ collaborations with advertising agencies, and how television and film have been used in public information, Letters, E1A:35, BCI:NAS.

- 59.

NSI’s annual report, E1A:36, BCI:NAS.

- 60.

Östling et al., “The History of Knowledge and the Circulation of Knowledge”.

- 61.

Haas, “Introduction”, 27.

- 62.

Letters, E1A:38, 43, BCI:NAS.

- 63.

Letters, E1A:46, BCI:NAS.

- 64.

Hyvönen et al., “The Formation of Swedish Media Studies, 1960–1980”.

- 65.

SOU 1969:48.

- 66.

Stjernholm, “A Clash of Ideals”.

- 67.

Betænkning 1977:787.

- 68.

“Referat fra utvalgets 10. Møte mandag den 15. November 1976”, 1976, E1A:50, BCI:NAS.

- 69.

“Referat fra utvalgets 10. Møte mandag den 15. November 1976”, 1976, E1A:50, BCI:NAS.

- 70.

Report, 25 September 1979, E1A:84, BCI:NAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Norén, F. (2023). Nordic Public Information: An Epistemic Community of Experiences and Ideas in the 1970s. In: Norén, F., Stjernholm, E., Thomson, C.C. (eds) Nordic Media Histories of Propaganda and Persuasion. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05171-5_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05171-5_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-05170-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-05171-5

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)