Abstract

This chapter underscores the importance of engaging policy makers and other stakeholders in the research process. Recognizing that there are two dimensions, the demand and supply sides to the use of evidence in policy making, it discusses the various instruments and platforms for communicating research to make it accessible to a variety of stakeholders.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The growing concern that scientific research and the academic community in general do not meaningfully engage the world of public policy is not entirely new. The “two communities” construct is widely used to describe the sharp disconnect between the worlds of academia and policy (Newman et al. 2015). This construct generally depicts the existence of an underutilization or, in most cases, non-utilization of scientific research in the policy making process. Although policy makers recognize that scientific research has the potential to largely inform and transform policy outcomes and is in fact an essential determinant of effective government decision making, wide communication gap continues to exist between both worlds.

There is a growing interest in connecting scientific research, with its rigour of methodology and finesse of analysis, to the world that it is expected to influence and change. It is indeed crucial to expand research findings beyond the boundaries of the academic community to reach policy makers as they intervene through their daily activities to solve societal problems. Furthermore, evidence from policy makers in various parts of the world shows that the quality of research does not automatically guarantee that it will make its way to the appropriate stakeholders and generate positive impact. Promoting the utilization of scientific research and supporting evidence-informed decision making at the political level requires a better understanding of the enablers. What are the major challenges that militate against collaboration and knowledge transfer from scientific research to policy making process? How can policy makers maximize the underutilized potentials in scientific research? What tools of communication are appropriate to make research accessible to various stakeholders?

A Movement for Policy-Engaged Research

Across the world the concern about evidence-informed policy making has gained traction. A few governments, like those of the United Kingdom and the United States, and non-state organizations like the International Rescue Committee and the Hewlett Foundation, have placed premium on policy-engaged research. They have invested efforts in moving relevant findings from research institutions and academic outlets to the policy process. Also, the Centre for Global Development and a few foundations have promoted the development of research through engagement with stakeholders and translating the outputs from research into forms that could reach a wider audience, especially stakeholders and strategic policy actors. Indeed, White (2019) considered the current state of the engagement as an evidence revolution. He identified four waves of the evidence revolution. He traced the first wave to the results agenda of the 1990s that came with the New Public Management or managerial movement in public administration. The emphasis was on outcome as against the previous focus on inputs. This was followed by efforts to develop indicators to measure performance. In the international development community, it witnessed the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals, later succeeded by the Sustainable Development Goals and the widespread use of the “Results Framework”. The limitations of the results framework as a measure of agency performance were that goals set by agencies were often too broad and affected by multiple factors for clear attribution.

The second wave was defined by the rise of the use of randomized control trials (RCTs) in impact evaluation and the emergence of the International Initiative for Impact Evaluation. The results from the burgeoning RCTs showed that interventions often do not work. They are often less than 20% in effect, with exception from some experiences in Africa. Wary of the duplication of dubious interventions that studies have shown to have no effects, some organizations such as the Department for International Development (DFID) and the Bill Melinda Gates Foundation demand a statement of evidence from rigorous studies to support new proposals. Furthermore, to establish buy-in, preference was given to a larger set of literature rather than a small number of studies. This led to the emergence and popularity of systematic literature reviews.

Systematic reviews marked the third wave of the evidence revolution. Systematic reviews for all their values posed problems of discoverability and accessibility by policy makers because they are long technical documents. There was need to translate lessons and ideas from these reviews for use by policy makers. He described the production of systematic reviews for use in the policy process as knowledge brokerage and knowledge translation.

He therefore named the fourth wave the brokering wave, defined by the emergence of “researchers whose incentive is to produce systematic reviews relevant for policy and practice”. These researchers are engaged in knowledge brokerage, by providing evidence as responses to the needs of government for informed decision making. Apart from doing reviews, these researchers connect with government agencies that need evidence to discuss priorities, available evidence and interpret them for decision making. They represent the part of an emerging evidence architecture that can institutionalize the use of evidence in policy making. He then described the dimensions of an emerging evidence architecture that will institutionalize the use of evidence in the policy process. Important parts of this architecture included legislation requiring evidence-based policy like the United States 2018 Evidence-based Policy Making Act, data bases that contain studies and reviews, evidence mapping and maps, evidence platforms for user-friendly products, evidence portals, guidelines and checklists. The evolving architecture has benefitted from the what works movement. The goals of the evidence movement can be advanced if the international development community invest in the evidence architecture beyond knowledge brokerage. He emphasized the need to undertake Evidence Ecosystem Assessment, Evidence gaps mapping and evidence-based budgeting. Finally, new technologies such as machine learning, big data and Artificial Intelligence constitute important factors in building the evidence architecture, according to White (2019). These technologies can facilitate systematic reviews, speed and accuracy of evidence synthesis. These mean that more investment on what works is required.

Demand and Supply Side Challenges in the Use of Scientific Research in the Policy Making Process

Despite the claim of an evidence revolution in the international development policy process, it is generally agreed that the use of evidence is not a settled matter in many countries. Indeed, the claim of an evolving architecture shows very clearly that there are major grounds yet to be covered even in the developed world. How many countries have legislations that require evidence-based policy making? In how many countries of the world can we point to an emerging evidence architecture? In Africa, a few countries have only begun to buy into establishing national evaluation policies and national evaluation systems. These mean that many African countries are still grappling with the results frameworks. As is often the case, many of the policies relating to monitoring and evaluation have been driven by donors and international development agencies such as the DFID. Thus, any engagement with research communication and the use of evidence in policy making must focus on both the demand and supply side. White’s ideas of the evidence architecture provide insight into what is emerging and future possibilities.

Studies on challenges of research communication and the use of evidence in policy have focused on three dimensions in bridging the gap between the world of research and policy (Wimberley and Morris 2007). The first dimension is focused on academics. The second is on practitioners and policy actors. The third is the intermediaries who broker within the policy process to promote interaction between the suppliers of research outputs and practitioners or actors who utilize research results for decision making. Thus, studies on research uptake for policy relate to both researchers who supply evidence and practitioners who use evidence in decision and policy making within the dynamic contexts of policy making processes around the world. Such studies also address various ways interventions can be made to smoothen and sustain the connections, to address the challenges of achieving evidence-informed policy making (Oliver and Cairney 2019). Some of these challenges are similar across the policy world, while others are contextual challenges, deriving from the nature of specific policy contexts (Wowk et al. 2017, Phoenix et al. 2019).

While the academic environment is a marketplace of contending ideas, the policy process is a place of contending values and interests. These mean that the researcher who wants to take her/his ideas to the policy process must recognize that her/his ideas would face scrutiny. Thus, the quality of research is considered very important and has consequences for the goal of influencing policy. Secondly, it cannot be assumed that policy makers are impervious to research ideas (Newman et al. 2015). Scholars must consider the various policy networks and communities, and the effective ways to engage them. In this regard, there are several prescriptions on offer to academics who want to make an impact on the policy process. A lot of the literature on research communication have focused on the supply side. Cairney and Oliver (2020) provide a survey of such prescriptions derived from concerns about breaking barrier and overcoming obstacles to communication between researchers and practitioners and advancing collaboration, recognizing that academic research is not traditionally designed to feed the policy process. These include the following:

-

Researchers should produce high-quality research.

-

They should evolve an effective means of communicating research with the goal of making it easier for policy makers to access research. This relates to presentation of the content of research outputs: the elimination of academic and disciplinary jargons, use of simple, readable and accessible language, aimed for the general and not the ignorant or specialist reader, and the use techniques and forms that can fit into and catch the attention of policy makers.

-

Engagement with the policy process. Researchers are urged to connect with practitioners, be accessible to policy makers, take advantage of windows of opportunity, and use intermediaries or knowledge brokers.

-

Pay attention to the context and process of policy and the key actors in the process.

-

Scholars must be entrepreneurial or active in the policy process, seek collaboration and build relationships.

-

Academics should co-produce knowledge with practitioners; this is considered one of the best guarantees of the use of evidence in the policy process.

It is however recognized that there are ethical dilemmas and practical challenges around these prescriptions faced by individual researchers in higher education. Indeed, there are several reasons why concern about policy relevance may not to be a priority for these researchers. Time, effort and resources are involved in trying to implement these prescriptions. Everyone cannot be excited by the possibilities and opportunities to make an impact in solving real-world problems. Besides, the probability of making such an impact is often remote as noted from the experience with the results framework even in developed countries (Cairney and Kwiatkowski 2017; Egbetokun et al. 2020).

From the perspectives of policy context, policy theory provides us with several ideas about the policy process that requires reflection concerning our expectation of promoting the use of evidence (Cairney and Oliver 2020). Academic institutions do not provide incentives for those interested in making an impact. In many universities, promotion is not tied to relevance and impact of research. Promotion is tied to publishing in professional and specialized journals of the various disciplines, through which academics communicate with one another, the scientific community. However, breaking out of the ivory tower and reaching out to practitioners may even require specific training or reorientation and few universities invest in such an enterprise. The policy conscious academic would have to go the extra mile of finding ways and means of implementing such prescriptions without institutional incentive.

Policy makers are usually faced with issues that offer a limited time for decision making while scientists take years to publish research findings and they examine issues over a long period of time. There may be a misfit of priorities between scientists and policy makers. The value of communicating one’s research findings with policy makers to produce accessible reports within a short time is not as valuable as securing funding for new research and publishing it in high-status journals with a long-time lag (Cairney 2016). Besides, there is a risk of failure to impact regardless of the efforts invested by the individual. This is because the payoff to engagement may be affected by choices already made and reinforced over time within the policy process.

In developing country contexts, there is a challenge of access to the policy process that is already saturated with agenda-laden ideas promoted by powerful western institutions backed by resources. In other words, the challenge of the academic in a developing context is complicated by an unequal access to the policy process. In many African countries, donors and international institutions have a hold in the policy process that may stand in the way of alternative ideas. Such organizations often support their policy preferences with funding that make it impossible for policy makers to resist. In many instances, international policy initiatives have supplanted national policy making (see Mkandawire 1997).

In general, it must be recognized that not all researchers would become interested in making a difference in the world regardless of the available incentive to do so. Some would be interested in extending the frontiers of knowledge with the hope that those interested in impacting would pick up their ideas for use in the policy process. Pielke (2007) provides a typology of policy orientations among scientists regarding influencing public policy: the pure scientist, the issue advocate, the science arbiter and the honest broker. These draw on the typology of research, in terms of the nature and purpose of research. For instance, a distinction is often made between basic and applied research. Basic research is not focused on intervention while applied research targets practice.

The research activities of the pure scientist have no consideration for use or utility of research outputs for decision makers. The importance attached to research is the original contribution to the repository of knowledge. It is the responsibility of those who want to use the knowledge to search for it. They can then draw on the knowledge to clarify and solve issues of public interests. Thus, the pure scientist remains removed from the messiness of policy and politics. This position is particularly appealing if it is recognized that evidence is not the only factor to be considered in public decision making. As noted earlier, in many universities, scholars do not have to demonstrate the impact of their work for promotion. Many scholars are quite content with their roles as scientists and feel not burden to impact the policy process.

On the other hand, the issue advocate is concerned about a political or ideological position and deploys research to advance a cause. The issue advocate is a programmatic scholar or scholar activist who aligns with an interest group or movement seeking to advance policy and politics. For scholars in this orientation, science must be engaged with policy and seek to participate in the decision-making process. This orientation relates with scholars who question the neutrality of science, the argument that values and preferences of the scientist come to play in the choice of issues and priorities of research which we find in critical theory, standpoint epistemologies and similar schools. For such scholars, scientists should be concerned about changing the world and bring scientific knowledge to serve the cause of justice and the public interest.

The third orientation is the science arbiter, who seeks to stay away from explicit considerations of policy and politics but recognizes that as experts or technocrats in society, he or she should provide advice when called upon by decision makers. Decision makers are sometimes confronted with specific questions that require expert judgement. Although the question originates from a debate among decision makers who are faced with practical issues, they require expert knowledge. Questions that can be resolved by science have to be taken to the experts. In this context, the scientist plays no role of an advocate, but that of an adjudicator, who may be on an assessment panel or advisory committee, providing policy makers objective scientific results, assessments or findings.

The fourth type, the honest broker, seeks to pursue the expansion of policy alternatives that can inform decision making by clarifying choices available to decision makers. The aim is to integrate scientific knowledge with stakeholder concerns in the form of alternative possible courses of action. It is recognized that there may be conflict of values among stakeholders and uncertainty in science. But a diversity of perspectives can help place scientific understandings in the context of a wide range of interests. Thus, the scholar concerned about influencing policy must recognize that he or she is part of a community of scholars as well recognize the difficulties of interacting with the policy community with its challenges and opportunities.

It is critical that scientists bring their research findings to bear on the policy process. In many instances, research findings have led to the development of policy agenda and the prioritization of certain issues and effective solutions. It is central to the policy sciences that research is focused on issues that are relevant to policy and decision making. Public policy scholars necessarily seek to address policy issues. This is shown in the level of engagement with the policy actors within the research process, from the conception, execution of research and the implementation of its policy recommendations.

Contemporary social science methodology affirms the need for research to play a vital role in transforming society by advancing socially relevant research findings. Ojebode et al. (2018) in a study conducted among 400 social science and humanities researchers found that whereas researchers held different views about the type of researcher Africa needed the most, most of them agreed that Africa did not need pure scientists as much as other types (honest brokers and issue advocates) based on Pielke’s (2007) categorization of researchers.

Public policy scholars conduct research to understand and improve public policy, to advance knowledge in a variety of policy issues and to conduct public policy research for government, business, think tanks and other research organizations. They are expected to actively seek to influence public policy making. This is because public policy as field of study is problem-solving oriented and seeks to provide intervention to address concrete human problems. Such scholars seek to provide expert knowledge in the form of evidence to inform policy making. To do this effectively, they must understand where and how public policy practitioners’ and policy makers get scientific information.

It is equally important to have a clear idea who the policy makers are regarding specific policy issues. Policy makers could include anyone from the president or leader of government, the legislators, the senior public servants, judges or even ordinary citizens. We include ordinary citizens because they sometimes play key roles as implementers, catalysts or beneficiaries of public policy. Hence, knowledge is required for them to be effective players. For instance, during the covid-19 pandemic the general populace was the target of policies to stem the spread of the virus. They were expected to sit at home, wear nose masks and regularly wash their hands. They need to be informed and convinced about the scientific basis of this requirement to achieve voluntary compliance. Without this information available to the public, achieving significant compliance would have been impossible given the level of resistance experienced all over the world.

In general, the news media is a major source of information for policy makers. Politicians who are elected to make public policy on behalf of their constituencies pay attention to the news. The media sets the agenda by reporting what is of interest to the various communities. Politicians pay attention to what matters to their constituents. The news media include newspapers and magazines, the broadcast platforms of television and radio, and social media such as twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and WhatsApp of which they get regular alerts. These media are ubiquitous and are influential sources of information.

In addition to the media, government agencies and departments produce reports and white papers to guide policy makers. Governments have think-tanks, regulatory agencies that monitor developments in such areas as environmental protection, drug administration, sanitation, etc. They also set up commissions to investigate issues such as the Panel of Inquiry frequently used in Nigeria, or the various Committees, (such as the Davis Tax Committee in South Africa) and Commissions of inquiry used across Africa. These bodies provide reports as source of policy decision making for both parliament and the executive arm of government.

Another source of information is the various public hearings organized by the legislature or any of its committees. These hearings provide opportunity for individuals and groups to present written memoranda or speak on issues of concern or focus on such hearing events.

These mean that policy researchers must use these opportunities to communicate research findings. It is becoming the norm that outputs from research are translated into forms that are accessible to policy makers. These included policy briefs, press releases or opinion pieces, blogs and twits. These can be circulated through traditional or social media. The assumption is that the barriers to evidence-informed policy from the perspective of the policy makers can be classified into three:

-

1.

Available evidence may not be used if policy makers are not aware of their existence and if the research evidence is not in a format that is accessible to policy maker. When policy makers do not have access to timely, quality and relevant research evidence, they resort to other sources of information beyond research. They may not be able to comprehend and identify the key messages from research outputs, not to talk of using the evidence from research outputs, including systematic reviews, if they are detailed and couched in technical language for their decision making. Policy makers may be overwhelmed by the vast amount of information they need to go through to deal with a particular case. Thus, research outputs must be presented in easily accessible format to facilitate their use.

-

2.

Even when research evidence is presented in accessible format and policy makers are aware of its existence, they may resist the use of evidence if the sub-cultures of policy making grant little importance to evidence-informed solutions. Some of them may prioritize their own opinion when research findings go against their expectations or against current policy. Thus, methods to disseminate evidence must be done in a way that policy makers will be open to receive and consider. There is need to recognize that policy makers tend to interpret new information based on their past attitudes and beliefs, much like the general population. Research evidence may be disregarded if it goes contrary to the political environment or ideological orientation of the prevailing government.

-

3.

Research needs to be sensitive to different contexts and the competitive environment of policy making. Several factors are implicated in the use or non-use of evidence in policy making. These factors include political and institutional factors such as the level of state centralization and democratization, the influence of external organizations and donors, the organization of bureaucracies and the social norms and values. This implies that policy makers make choices between different priorities while taking into consideration the limited resources available. When policy makers engage scientific research, they make judgements that balances different opinions, as well as claims and counterclaims from interest groups, including scientists. Policy makers do not necessarily hold the same value orientations with scientists on the drive to produce scientific knowledge. They do not see scientific knowledge as less biased than other forms of knowledge such as community and cultural knowledge (Cairney 2016)

The various platforms listed above for the dissemination of research evidence are useful to achieve uptake because they enable research findings to be more accessible to non-scientific audiences and policy makers. A blog writing is easily accessed and digested by a broad audience who can understand and perhaps apply the key messages from the research output. In addition, a blog creates the opportunity for a more conversational interaction with the audience than an academic publication. By using techniques such as good keyword identification, it is more likely to rank more highly in search engines, increasing the visibility and uptake of blog post. Converting the research output into a blog post enables the researcher to present academic papers, including the title used, in a way that engage with the audience. By converting a research paper to a blog, researchers achieve the positive flow-on effect of research outputs, distilling and presenting some of the key messages for a defined audience. They can also amplify those messages to create a convincing story.

Policy briefs are an information-packaging documents used to support evidence-informed policy making. The name policy brief may also be used interchangeably with the technical note, policy note, evidence brief, evidence summary, research snapshot, etc. (Dagenais and Ridde 2018). A policy brief is easier to handle by policy makers than systematic reviews because they are precise documents, taking into consideration the time scales and simplicity required by a non-technical audience. The policy brief may be used to clarify and improve the understanding of a problem or a situation, to confirm or justify a decision or a choice, which has already been made (Arnautu, Diana and Christian Dagenais 2021). The policy brief presents the evidence in a manner that is easily identified, interpreted and considered to better inform the parties involved in a policy issue.

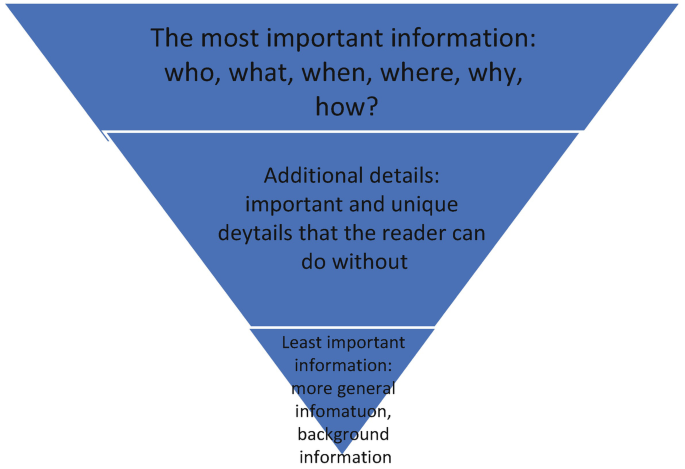

There are tools for transforming technical writing, that is the output from scientific research in easy, straightforward manner. They enable the presentation of the main points or key messages of a scientific research. These include the inverted pyramid and the message box. The inverted pyramid is a story-telling tool usually used in news reporting (Fig. 11.1). The inverted pyramid style presents information in a descending order of importance with the most crucial details presented first. This enables readers to get the most important information so that they can decide quickly whether to continue or stop reading the story (Scalan 2003).

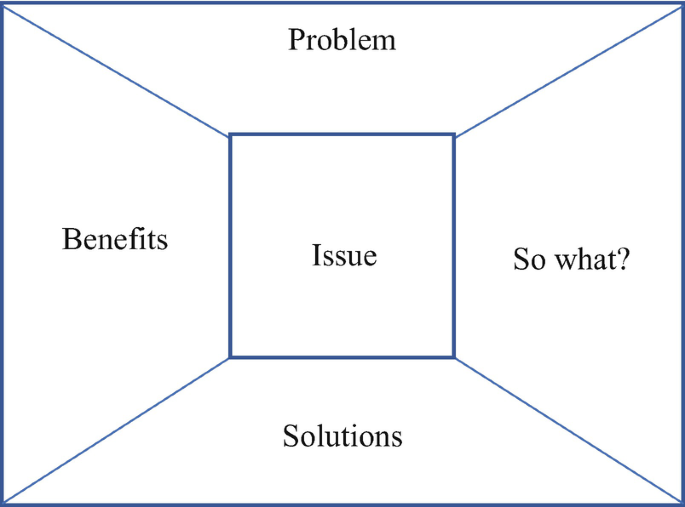

Similarly, the message box helps to explain what the research output is about and why it matters to the policy maker or the journalist (Fig. 11.2). It can be used to prepare for interviews with the media, frame a policy brief or press release, structure a presentation or an opinion piece. The message box can also serve as a tool to clarify the main issues of a research, the relevance of the research to the specific audience, and for condensing content of the research work into five to six sentences stating the problem, potential solutions and how the research relates to the concerns of the audience (Baron 2010: 108). The resulting set of concise messages can be disseminated using channels appropriate for the end user, ranging from social media, to newspapers, to policy briefings and events.

These tools enable research outputs to be presented in a concise, easy to examine, understandable, user-friendly forms. They enable research outputs to be tailored and targeted to specific audiences with simple and clear messages focused on required information and recommendations. Usually, such presentations contain a link to the original journal article or source.

Research dissemination in contemporary times can be carried out in different ways, from long reports to policy briefs, message boxes, blog posts, social media posts, presentations and many more. Other means of disseminating research may take the form of engagement events by stakeholders to review the content and process of research. These include events in the form of round tables, town hall meetings, workshops, etc., involving exchanges and interactions among scholars, advocates and policy makers. They also include media interviews, writing blog features and data visualization, and social media content creation. However, determining the appropriate tool of communicating research is dependent on who the policy makers are and the kind of research being conducted. Communicating research work can adopt a multi-layered approach.

There is no scarcity of ideas how to engage the policy process. Several scholars have drawn ideas from their experiences in engagement with the policy process, others draw on the experiences of brokers or tease out ideas from policy theory and psychology. Engagements relates directly to the methodology of research. If research is directed at meeting broad policy objectives, then engagement with policy makers should be incorporated right from the inception of the research. Engagement facilitates the effective definition of questions to address the concerns of policy makers. When policy makers are engaged in the formulation of research questions, the research becomes more policy relevant. Evidence-based research is only relevant to policy making if it addresses the key policies at hand, is applicable to a local context and is constructed to meet policy needs. To enhance the possibility of a policy-engaged research, scientists must be open and willing to engage policy makers in the research process.

Conclusion

For social science research to be relevant for policy making, researchers and policy makers must understand their relevance and roles in the knowledge production process. Both parties need a shared understanding of the significance of these roles in policy making and implementation. Africa’s urgent problems require the expertise of policy-engaged researchers who would engage policy actors and politics. Engagement and effective communication of research would benefit society.

Efforts must be made by research communities to create engagement platforms between scientists and researchers. These platforms will ensure that policy makers are carried along at each step of the research process, thereby moving away from the common methods of engagement that reduces policy makers and other non-scientists to mere subjects of scientific research. A close interaction with policy makers on choice of method, design of instruments and major aspects of the research work stimulates an atmosphere of co-knowledge production between both worlds.

Although research communication involves distilling the key findings of high-quality research and presenting them in a format that non-scientists and policy makers can understand, interpret and use for decision making, the relevance of research will not be improved by mere speculations of policy needs and improvement in tools of communication. Effective communication involves developing relationships with stakeholders in the research process. The existence of good-quality research is not sufficient for evidence-informed policy making, a difficult task that requires interventions from both the demand and supply sides of policy-relevant research. Knowledge brokerage should be encouraged to facilitate the use of evidence in the policy processes of African governments by regional bodies like the African Union that has demonstrated capacity to promote policy diffusion across the continent.

References

Arnautu, Diana, and Christian Dagenais. 2021. Use and Effectiveness of Policy Briefs as a Knowledge Transfer Tool: A Scoping Review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8: 211. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00885-9.

Baron, Nancy. 2010. Escape from the Ivory Tower: A Guide to Making Your Science Matter. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Cairney, P. 2016. The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cairney, Paul, and Richard Kwiatkowski. 2017. How to Communicate Effectively with Policymakers: Combine insights from Psychology and Policy Studies. Palgrave Communication 3 (7): 1–7.

Cairney, Paul, and Kathryn Oliver. 2020. How Should Academics Engage in Policymaking to Achieve Impact. Political Studies Review 18 (2): 228–244.

Dagenais, C., and V. Ridde. 2018. Policy Brief (PB) as a Knowledge Transfer Tool: To “make a splash”, Your PB Must First Be Read. Gaceta Sanitaria 32 (3): 203–205.

Egbetokun, A., A. Olofinyehun, Aderonke R. Ayo-Lawal, and M. Sanni. 2020. Doing Research in Nigeria Country Report Assessing Science Research System in a Global Perspective. National Centre for Technology Management and the Global Development Network.

Mkandawire, T. 1997. The Social Sciences in Africa: Breaking Local Barriers and Negotiating International Presence. African Studies Review 40 (2): 15–36.

Newman, Joshua, Andrian Cherney, and Brian W. Head. 2015. Do Policy Makers Use Academic Research Reexamining the Two Communities Theory of Research Utilisation. Public Administration Review 76 (1): 24–32.

Ojebode, Ayobami, Babatunde Raphael Ojebuyi, Oyewole Adekunle Oladapo, and Obasanjo Joseph Oyedele. 2018. Mono-Method Research Approach and Scholar–Policy Disengagement in Nigerian Communication Research, in 369–383. In The Palgrave Handbook of Media and Communication Research in Africa, ed. Bruce Mutsvairo. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Oliver, K., and P. Cairney. 2019. The Dos and Don’ts of Influencing Policy: A Systematic Review of Advice to Academics. Palgrave Communications 5 (21): 1–11.

Phoenix, Jessica H., Lucy G. Atkinson, and Hannah Baker. 2019. Creating and Communicating Social Research for Policymakers in Government. Palgrave Communication 5 (98): 1–11.

Pielke, Jr., R.A. 2007. The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scalan, C. 2003. Birth of the Inverted Pyramid: A Child of Technology, Commerce and History, Poynter. https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2003/birth-of-the-inverted-pyramid-a-child-of-technology-commerce-and-history/.

White, Howard. 2019. The Twenty-First Century Experimenting Society: The Four Waves of the Evidence Revolution. Palgrave Communication 5 (4): 1–7.

Wimberley, Ronald C., and Libby V. Morris. 2007. Communicating Research to Policymakers. American Sociologist 38: 288–293.

Wowk, Katerya, Larry Mckinney, Frank Muller-Karger, Russell Moll, Susan Avery, Elva Escobar-Briones, David Yoskowitz, and Richard McLaughliun. 2017. Evolving Academic Culture to Meet Societal Needs. Palgrave Communication 3 (35): 1–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Aiyede, E.R. (2023). From Research to Policy Action: Communicating Research for Public Policy Making. In: Aiyede, E.R., Muganda, B. (eds) Public Policy and Research in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99724-3_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99724-3_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-99723-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-99724-3

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)