Abstract

The process of reopening of college campuses in response to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic sheds light on underlying features of the educational system. Understanding the various models of reopening gives us insight into how the education system is structured through the responses of the various college campuses—a unique opportunity to capturing issues of inertial momentum against change in the past, and projecting into the future. We propose visualizing the structure of a system problem as a way to allow the problem to become visible through mental models. We illustrate our approach through causal loops—the core tool for systems thinking. We discuss the construction of one visual model, based on publicly available resources, to be used as a starting point for a discussion. The model points to the importance of making informed, high-level early decisions, in the case of a crisis, as this shows to be a highly dependent variable in the model. This finding is shown to be supported by ongoing research on faculty adaptability in different contexts. Visualizing mental models in systems thinking does not seek to unnecessarily capture all the details of the complexity of the educational system; rather, it aims to externalize deep problems, which, in turn, demonstrate opportunities for transformation in the future.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction: The Pandemic Outbreak as a Systems Problem

The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak caused an unprecedented disruption to the ways our lives are organized and the ways the systems of our society function. The interconnectivity between and among elements became explicit, and elements that seemed unrelated became central. A system can broadly be defined as a group of interdependent elements that interact to achieve a common goal (see, for example, Kauffman (1980) and https://thesystemsthinker.com/). There are five key characteristics of a collection of entities to act as system (King et al., 2020): interdependence; collective behavior to achieve a common function; long-term consequences; a behavior that is dependent on the system’s structure; and multiple views of the system based on the beliefs and values of the stakeholders. In this chapter, we attempt to explore some of these underlying aspects of the higher education system as it responded to the COVID-19 pandemic.

2 Visualizing Systems Thinking

2.1 Systems Thinking: Framing the Problem

The process of framing the system problem usually starts by asking the following questions: Who are the stakeholders? What are the behaviors of the problem that stakeholders agree on their existence? What contributes to the problem? And what are the consequences of the problem? Asking these questions serves the purpose of clarifying key features of the problem as well as setting the system’s boundaries (King et al., 2020). Because different stakeholders have different mental models of how the components of a systems are connected and interacting, there is no single visual representation of the system (Meadows, 2008). Furthermore, there is no single representation that captures the entirety of the system (Senge, 2006). Therefore, visualizing systems thinking becomes necessary to bring together different viewpoints (see, for example, https://waterscenterst.org/). The practice of systems thinking visualization does not seek to find the ultimate representation of the system (Fortmann-Roe & Bellinger, 2013); rather, the result is a fruitful discourse about the system, its elements, and the way they are connected, which will enable the identification of leverage points that can change the behavior of the system by changing its underlying structure (Zhou, 2016).

2.2 Problem Statement: Visualizing the System Using Mental Models

In this chapter, we seek to visualize the structure of the system, as conceived by stakeholder, by identifying the elements of the system and their relationships using causal loops . Here, mental models are defined as factors that influence “how people understand and act in the world” (King et al., 2020, p. 5). As a core tool in systems thinking (King et al., 2020), causal loops enable the identification of leverage points; i.e., places to intervene within a system (Meadows, 1999). In the visual representation of a system, the variables of the system (i.e., its components that can change over time) are connected with causal links (i.e., arrows that represent directional cause-effect relationship between variables). The advantage of causal loops is that they focus the problem analysis on the interacting variables in play, without giving unnecessary attention to merely relevant factors in the problem. An example of a causal loop is illustrated in Fig. 5.1, where a positive sign on an arrow indicates similar directionality of change in variables (e.g., a decrease in one variable causes a decrease in the other connected variable) and a negative sign indicates the opposite (an increase in one variable causes a decrease in the other connected variable). Different archetypes of systems structures based on how the variables are connected and interacting have been identified (Acaroglu, 2017).

3 Visualizing System Structure in Response to the Pandemic

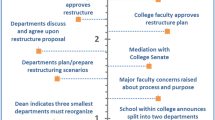

In this section, a visualization of the system structure of campus reopening models during the pandemic is introduced, Fig. 5.2. The rationale behind the construction of this visualization is provided in the following section. In order to identify the structure of the system, we need to identify the variables that contribute to the problem. Our method is based on systematically documenting the sequence of events that took place when discussing reopening, starting in July 2020 through July 2021, and as reported in publicly available news media outlets. No single effort can capture the entire complexity of the problem of reopening campuses. Furthermore, stakeholders may not benefit from highly detailed relationships that seek to capture high-resolution interactions between variables. Instead, stakeholders can benefit from characterization of focused differences in the perspective of a system. Table 5.1 provides a potential list of variables of the system. The list is provided as variables, backed up with evidence of their existence and interactions with other variables. The list is provided as a starting point to generate causal loops. The publicly shared decisions by different campuses on how to proceed with reopening highlight what has been important in making the decisions, what influenced the decisions and how the decisions have changed over time.

4 Discussion: Reopening Models

The discussion below focuses on the early phases of responding to the pandemic and is divided into two timeframes: July 2020—December 2020 and January 2021—July 2021. The early phases are particularly unique to study as they were characterized by both emergent and uncertainty in responding to the crisis. As more knowledge about the pandemic was gained, more formal processes started to be put in place. For this reason, the chronological analysis provided here gains its value from the understanding that different institutions followed similar or different processes to varying degrees. It is not the goal here to capture this variation at a minute level; instead, the goal here is having a high-level visualization with both illustrative and substantial examples.

4.1 Timeframe: July 2020—December 2020

To illustrate the “(A) Availability of on-campus living ” variable, consider the reopening plans issued by both Harvard University (2020) and Rutgers. (2020) in July 2020. The plans indicated intentions to allow students to live on campus in the Fall, with few courses offered in-person. In the same month, four higher education institutions leaders testified before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Higher Education Subcommittee on how the pandemic has exposed the “(B) levels of inequities ”: “The suspension of on-campus activities is also threatening many students’ access to basic essentials like food and housing. For these students, going to school had been their primary way of meeting these needs” (Davis, 2020). As to the impact on “(C) Athletic activities ,” heads of preeminent conferences have indicated concerns for the upcoming season (Adelson, 2020). The compounded effect of various factors on “(D) College finances ” was illustrated in an analysis in The New York Times in August 2020: “Many college administrators rightly fear they will lose students to their competitors” (Dynarski, 2020). Lack of on-campus activities called for layoffs. In December, George Washington University reported layoffs of 339 positions, saving $32 million (Schonfeld, 2020).

Throughout the pandemic, a constant concern has been “(E) Students gathering .” In August 2020, Pennsylvania State University president, Eric Barron, described how the students were flouting pandemic measures (Penn State, 2020). In the same month, the chancellor of the University of Kansas, Douglas Girod, said the “large majority” of students who had tested positive were members of fraternities and sororities (Girod, 2020). As Labor Day weekend approached in September 2020, The White House’s coronavirus-response coordinator, Deborah Birx, urged college students to be tested (Johnson, 2020). The issue of “(F) Holiday travels ” was a concern again in November 2020. Three New York colleges shifted to remote offerings as the state experienced a surge with the Thanksgiving holiday approach: Syracuse University (Weaver, 2020), the University at Albany (NBC, 2020), and Niagara University (Watson & McNeil, 2020). By the end of the 2020, some colleges made the “(G) Early decision ” to continue remote learning in Spring 2020. In North Carolina, the three campuses that were among the first to pursue remote instruction in Fall 2020 (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, North Carolina State University, and East Carolina University), were also among the first to announce resuming in-person instruction in Spring 2020 (Thomason, 2020). The chancellor of California State University, one of the U.S. largest public-university systems, Timothy White, made this decision early in September 2020: “This decision is the only responsible one available to us at this time” (White, 2020). On other campuses, however, decisions to resume in-person instruction were not received without tension. Early decision in September 2020 by the University of Wisconsin at Madison to resume in-person instruction was received by the Dane County Executive Office with condemnation, calling all instruction to be moved online (Blank, 2020; Vruwink, 2020).

The issue of making early decisions, of whether to pursue remote or in-person learning, was very crucial. Making early decisions was connected with “(H) increased understanding of the virus.” In October 2020, a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found evidence that cases among 18- to 24-year-olds had regularly preceded spikes in infection among older people (Oster et al., 2020). In the same month, Boston University started to require digital virus-status badges on campus (Sweeney, 2020). Boston University, in November 2020, threatened discipline for students who did not get tested after being notified that they were overdue for a test (Elmore, 2020), “(I) Testing .” In November 2020, Princeton announced its reopening plans to undergraduates in Spring 2021, requiring regular testing (Eisgruber, 2020). Despite the pandemic, some colleges, e.g., Georgia Colleges (Stirgus, 2020), witnessed an increase in enrollment of fresh high school “(J) new students,” at the time when the pandemic has depressed enrollment nationwide (June, 2020).

The increased availability of testing by the end of 2020 prompted the U.S. government to start providing more “(K) Government guidance .” With the transition to the new administration in the US in the same time frame, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, noted to college leaders to expect more central coordination of COVID-19 policies under the new administration (Burns, 2020). In December 2020, the National Academies released two sets of recommendations: one on campus coronavirus testing (2020a), and another encouraging safe student behavior (2020b).

4.2 Timeframe: January 2021—July 2021

In January 2021, the UC-San Diego installed vending machines for COVID-19 tests (UC-San Diego, 2021). The beginning of Spring witnessed announcements of “(L) Changing of plans ” from some campuses. For example, Stanford University, canceled plans to bring students back for the Winter Quarter (Tessier-Lavigne & Drell, 2021). As “(M) Vaccines ” became available in January 2021, plans to reopen campuses became clearer (NYC Health, 2021), allowing administrators to make decisions early (Thomason, 2021). However, a report published on the Social Science Research Network observed that sociopolitical factors, stronger than public health factors, influenced the reopening decision (Collier et al., 2021).

Closing the loop in Fig. 5.2, by early 2021, the impact of the pandemic on “(D) College finances ” became clearer. Iowa public universities lost millions in room and board revenue (Miller, 2021). In community colleges, enrollment dropped 18% from graduates of low-income schools, and 8.8% from graduates of higher-income schools (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2021). Some colleges started to face lawsuits for not offering in-person instruction during the pandemic (Gluckman, 2021). By March 2021, administrators appreciated the importance of “(G) Making early decisions .” For example, The University of Alabama system (2021), Ohio University (2021a), Temple University (Englert, 2021), and many others (Mangan, 2021) announced plans to offer in-person instruction in the Fall. By April 2021, some colleges, e.g., Cornell University (Pollack, 2021) and Rutgers University (Devlin, 2021), made “(M) Vaccination ” a requirement to be enrolled in-person in Fall 2021. Some universities, e.g., Siena College in New York (Siena, 2021), Ohio University (2021b), and University of Tennessee at Knoxville (2021), offered an incentive for students to get vaccinated. However, some groups challenged making vaccination as a requirement, e.g., the Informed Consent Action Network (https://www.icandecide.org/).

By Summer, more efforts to “(H) Understand the virus” continued, despite struggles in recruiting participants to understand transmission in higher education (Cirruzzo, 2021; Ellis, 2021). In June, the CDC (2021) released new (“(K) guidance”) on how colleges can operate safely given the condition that everyone has been fully (“(M) vaccinated”). By the end of June 2021, some colleges have started to relax preventive measure, e.g., masking mandates, with reports of continued drop in positive cases (“(I) Testing”) (Mull, 2021).

5 Conclusion: Implications for Emergency Situations

Visualizing systems thinking using causal loops provides insights into the interdependence of variables. The visual structure reveals, through discussions amongst stakeholders, deep problems within the system, as well as opportunities for transformation. In the model we constructed here, variable (G), “Making early decisions ,” was found to be the most consequential variable in the system (i.e., the ultimate sink in the causal loop). In an ongoing study of faculty adaptability (Ali et al., 2021), participating faculty alluded to the same point. One participant commented on the issue as follows: “I found last summer [2020] to be really frustrating because I wanted some certainty about what was going to happen, and the university was unable to provide any certainty.” Another faculty commented that the, “biggest barrier was probably the fact that my university couldn’t see that the train that was coming in the sense that we’re going to be virtual.” Overall, the benefit of visualizing systems structures is that they provide goal orientation, act as indicators of variables that affect response time and clarify variations of mental models of how stakeholders perceive of a problem. A promising area of research is identifying differences between mental models of administrators (those who make high-level decisions) and mental models of faculty members (those who are at the front line of action during an emergency). Such differences in mental models point to leverage points to create effective change.

References

Acaroglu, L. (2017). Tools for systems thinkers: The 12 recurring systems archetypes. Disruptive Design.

Adelson, A. (2020, July 11). SEC commissioner Greg Sankey: Concern about football season ‘high to very high’. ESPN.

Ali, H., McKenna, A., Bekki, J., & Roscoe, R. (2021). Conceptualizing faculty adaptability in enacting curricular change. In Paper presented at 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference.

Blank, R. (2020, September 21). Chancellor Blank to county executive: Partner with us in enforcing safe behavior off-campus. University of Wisconsin-Madison News.

Burns, H. (2020, December 9). Fauci to colleges: Expect a more centralized Covid policy under Biden. The Business Journals.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2021, June 24). Guidance for Institutions of Higher Education (IHEs). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Cirruzzo, C. (2021, May 6). College students are helping answer key vaccine questions, but finding enough of them is tough. U.S. News & World Report.

Collier, D., Fitzpatrick, D., Dell, M., Snideman, S., Marsicano, C. & Kelchen, R. (2021, February 3). We want you back: Uncovering the influences on in-person instructional operations in fall 2020. (C2i Working Paper Series, No. 210101).

Davis, S. (2020, July 7). Opening statement of chairwoman Susan Davis (CA-53). In Subcommittee on Higher Education and Workforce Investment Hearing.

Devlin, D. (2021, March 25). The university will require all students to be vaccinated before arriving on campus in the fall. Rutgers Today.

Dynarski, S. (2020, August 17). The United States is reopening many of the wrong schools. The New York Times.

Eisgruber, C. (2020, November 4). President Eisgruber’s spring 2021 update: All enrolled students invited to campus. Princeton University News.

Ellis, L. (2021, March 26). When the campus becomes a lab to study covid. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Elmore, K. (2020, November 2). COVID-19 compliance and enforcement. Boston University: Dean of Students.

Englert, R. (2021, March 21). Some optimistic news about the fall. Temple Now.

Fortmann-Roe, S., & Bellinger, G. (2013). Beyond connecting the dots: Modeling for meaningful results. InsightMaker. http://beyondconnectingthedots.com/

Girod, D. (2020, August 20). Message: Updating our community on COVID-19 testing results. In Office of the Chancellor. The University of Kansas.

Gluckman, N. (2021, March 11). Federal judge dismisses tuition-refund lawsuits against 4 Rhode Island universities. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Harvard University. (2020). Decision for 2020–21 academic year.

Johnson, S. (2020, August 31). During Madison visit, Deborah Birx urges college students to avoid crowds, wear masks. Wisconsin Public Radio.

June, A. (2020, November 12). Undergraduate-enrollment picture worsens as pandemic drags on. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Kauffman, D. (1980). Systems one: An introduction to systems thinking. Future Systems, Incorporated.

King, K., Romero, M., Prince, K., & Swanson, J. (2020). Looking beneath the surface: The education changemaker’s guidebook to systems thinking. KnowledgeWorks.

Mangan, K. (2021, February 19). Could fall bring some return to normalcy? These colleges say yes. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Meadows, D. (2008). Thinking in systems. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points: Places to intervene in a system. The Sustainability Institute.

Miller, V. (2021, February 22). Dorms at Iowa universities lose tens of million in pandemic. The Gazette.

Mull, R. (2021, June 18). Some colleges are loosening their mask mandates: Here’s a list. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020a). COVID-19 testing strategies for colleges and universities. The National Academies Press.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020b). Encouraging protective COVID-19 behaviors among college students. The National Academies Press.

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. (2021, March). High school benchmarks: COVID-19 special analysis update & correction. National Student Clearinghouse Research Center.

NBC. (2020, November 10). Two of the biggest upstate NY universities switch to remote learning as virus surges. NBCNewYork.

NYC Health. (2021). COVID-19: Vaccination requirements. NYC Government.

Ohio University. (2021a, March 3). OHIO to welcome all students, increase in-person activities for summer and fall 2021. OHIO News.

Ohio University. (2021b). COVID-19 testing incentive program. Be Safe Bobcats: Coronavirus Response.

Oster, A., Caruso, E., DeVies, J., Hartnett, K., & Boehmer, T. (2020). Transmission dynamics by age group in Covid-19 hotspot counties—United States, April–September 2020. (Rep 2020; 69: 1494–1496). MMWR, Morb Mortal Wkly.

State, P. (2020). President Eric Barron shares message with the community. Penn State News.

Pollack, M. (2021). Cornell releases plans for fall return to campus. Cornell Chronicle.

Rutgers. (2020, July 6). Our plans for fall 2020. Office of the President.

Schonfeld, Z. (2020, December 11). Officials conclude expected layoffs as part of COVID-19 financial mitigation. The GW Hatchet.

Senge. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Currency.

Siena. (2021). All residential and commuter students vaccine eligible on April 6. Siena College in New York: Marketing, Communications and Public Affairs.

Stirgus, E. (2020, November 11). More students in Georgia’s public university system despite pandemic. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Sweeney, E. (2020, October 22). Boston University students must show digital COVID-19 badges on campus. MSN.

Tessier-Lavigne, M., & Drell, P. (2021). Change in our winter undergraduate plan. Stanford Today.

Thomason, A. (2020, October 1). 3 Campuses that flipped online plan to welcome students back next spring. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Thomason, A. (2021, February 12). More colleges envision returning to in-person learning this fall. The Chronicle of Higher Education.

UC-San Diego. (2021). Testing and screening. Return to learn. UC San Diego.

University of Alabama System. (2021, March 1). UA system campuses plan return to full, in-person classes for fall 2021. UA System News.

University of Tennessee at Knoxville. (2021). Participation incentives for COVID-19 testing and screening. Center for Health Education & Wellness.

Vruwink, A. (2020, September 20). Parisi: Covid-19 continues to spread quickly in community, renews call for UW campus to go virtual. County of Dane Executive Office.

Watson, S., & McNeil, H. (2020, November 10). Covid-19 cluster at Niagara University reaches 99 cases; university will go to all-remote learning. The Buffalo News.

Weaver, T. (2020, November 11). Syracuse University is just 14 coronavirus cases away from all-remote classes. Syracuse.com.

White. (2020). Chancellor’s message. The California State University: Office of the Chancellor.

Zhou, J. (2016). Systems & Us. Systems and Us. Embracing Complexity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ali, H., McKenna, A. (2022). Reopening Campuses: Visualizing the Structure of a System Problem. In: Dennen, V., Dickson-Deane, C., Ge, X., Ifenthaler, D., Murthy, S., Richardson, J.C. (eds) Global Perspectives on Educational Innovations for Emergency Situations. Educational Communications and Technology: Issues and Innovations. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99634-5_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99634-5_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-99633-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-99634-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)