Abstract

Innovation is at its best when we are thrusted into an emergency situation that tests protocols and established norms. In this chapter, authors reflect on the journey of a team of instructional designers in an online learning design unit of a large mid-western university amidst COVID-19. With the influx of a multitude of courses to be transitioned to the online platform, authors describe challenges faced by their unit, coping mechanisms, and lessons learned during this phase. They describe inclusive design thinking and uninterrupted practice in return to robust instructional design models, such as Understanding by Design and Universal Design for Learning. The chapter concludes with examples of tried and tested internal tools and an adaptive workflow catering to a shortened development timeline. These practices and reflections serve as a guiding light as the global world navigates online learning to meet increasing demands of new-age digital accessibility and online course design considerations in higher education beyond COVID-19.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Online learning

- Understanding by design (UbD)

- Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

- Design thinking

- Adapted workflow

1 Introduction

COVID-19 transformed our everyday paradise into pandemonium (Milton, 2000). Established norms in our day-to-day operations had to be recalibrated to form new protocols. The higher education realm was no different. With the onset of the pandemic, institutions of higher education scrambled to move learning opportunities to the online environment in hopes of offering an uninterrupted experience for learners. Instructors, with or without any online teaching experience, were thrusted with emergency remote teaching (ERT) (UNESCO, 2020). However, ERT courses had a much shorter timeframe for a COVID-19 forced transition, which brought forth various challenges in the quality of design, issues with digital accessibility, course design equity and inclusivity regarding student identities, e.g. culture, race, gender, ability, and various socio-economic issues (Jandrić et al., 2020; Beaunoyer et al., 2020).

The new role of online learning post COVID-19 was undeniably inevitable due to flexibility and growth opportunities it presented (Ali, 2020). However, if this modality is to play a more critical role in the years to come, it is paramount to establish a course design infrastructure, based on time-tested evidence-based models and practices, not only to support and enhance student learning but to prove sustainable and accessible. Ultimately, progress in online course design should mean adequately addressing the needs of diverse learners along with adapting to an abbreviated development timeline, if need be.

It is with this perspective that we present this chapter, wherein we showcase the reflections of our team of instructional designers (IDs) of an online learning design unit of a large U.S. Midwestern university during pandemic times. The unit, as it will be referenced moving forward, was entrusted with transitioning over 70 courses to online environment within a span of 10–12 weeks for a fall 2020 offering. This transition would be in addition to the 150 online-by-design courses already planned for the semester. The sudden surge of courses presented the unit with unique challenges related to abbreviated development timeline, optimizing course design workflow, efficient use of resources, and working with novice online instructors.

This chapter offers the context, challenges and a reflection of the lessons learned that proved sustainable and robust to online course design during this transition. It discusses coping mechanisms, recalibrated design processes and workflow guided by established frameworks, i.e., Understanding by Design (UbD) and Universal Design for Learning (UDL). The chapter concludes with a proffer to higher education in the form of a survival toolkit consisting of four tenable artifacts. Course designers, instructors and administrators might benefit from these shared insights, not only during an emergent situation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, but moving beyond and to new norms.

2 Context

The online learning design unit of this large mid-western university supports online courses for the colleges of engineering and liberal arts and sciences. Historically, the unit provided grants for instructors interested in creating new asynchronous online and blended courses and/or converting from a face-to-face format to online learning. Apart from the monetary incentive, the grant included the support of a skilled Instructional Designer (ID) who collaborated with the instructor on pedagogical, technical, and instructional needs. Such courses are known as ‘online-by-design’ courses.

Course development cycle of 16–18 weeks, for ‘online-by-design’ courses, begins when the instructor collaborates with the assigned ID after receiving the grant. Briefly, the four design phases are: Planning —where the front-end analysis is undertaken along with creating a design blueprint. Guided by the UbD framework and backward-design model, desired outcomes are first identified, then evidences for such outcomes are designed and finally necessary learning experiences are planned (Wiggins & McTighe, 2012). Planning phase is iterative, collaborative and an incremental process between the instructor and designer. Production —Learning activities, assessments and interaction strategies are developed along with the course setup in Canvas Learning Management System. Implementation —Students are able to access the course and their learning experience begins once the course is published. The course climate relies on communication prompts, feedback and guidance by the instructor. Continuous Feedback —Two surveys administered to students, at the start and mid-semester, provide feedback about course navigation and design. Survey responses feed into the continuous evaluation and improvement cycle. Along with the surveys, a semi-structured interview or debrief, is conducted after the first offering of the course to discuss the instructor’s experience of designing and teaching the online course.

The year 2020 has been exceptional. The aforementioned typical workflow could not be followed due to an influx of a high volume of additional courses in the queue, waiting to be transitioned online within a short span. The following sections describe the challenges faced by the unit, the adapted workflow and its rationale.

3 Challenges

There were three distinct challenges faced by the unit: (1) an increased workload, (2) a shortened course design timeline and (3) working with novice online instructors. Approximately 70 new online courses were added, in addition to the planned online-by-design courses, totaling 150 multi-section courses for fall 2020. This represented a 20% increase in the volume of courses handled by the unit. The unit was temporarily restructured to cope with the increased workload; based on level of experience, each ID was assigned to particular courses for continuity and consistency. For uninterrupted support, two IDs were assigned per course, one primary and one secondary.

The development time was abbreviated; a typical 16–18-week course design cycle was reduced to 10–12 weeks. Optimizing the design workflow and making efficient use of available resources became integral. In view of the emergent situation and to ensure a learner-centric quality product, the unit inventoried resources and shortlisted four internal tools—a survey, a template and two checklists.

It was equally important for the unit to support novice instructors in this transition endeavor. Each ID met one-on-one with assigned instructors in an effort to understand the needs of both the course and instructor. IDs explained each step of the design process, clarified misconceptions, shared online learning and teaching guidelines and best practices and provided overall guidance.

4 Back to Design Basics

Importance of Design Thinking

Design thinking , a strategy woven into the fabric of institutions, embraces the idea of observing user behaviors, including feedback in course creation, and adjusting to user needs. More importantly, design thinking relies on a high level of empathy and care ethics that lead to solutions created out of user experiences (Wiggins & McTighe, 2012).

During the transition effort, some instructors were novices to online learning, and design thinking mindsets were in demand. As a team of IDs, we often pondered on overarching design approaches and strategies both for course design and interactions with instructors. As we prepared to support the influx of courses during COVID-19, our thinking was no different. Design thinking means doing so with, not for the instructor and student. The people who make up the unit recognize and acknowledge the importance of partnering with instructors and students in the design of the course. However, during the emergent situation, this partnership also had to be optimized while remaining steadfast in design thinking practices. Doing so entailed:

-

Keeping the development phase collaborative and incremental

-

Empathizing with instructors’ needs, apprehensions, and comfort-level with technology

-

Responding promptly to instructor questions and concerns

-

Providing immediate support in areas, as needed

-

Setting a mutually acceptable channel of communication

-

Reviewing prior student-feedback requested from instructors

Because instructors may not always recognize how design thinking is operationalized, it was important for the unit to trust in the instructor-ID partnership to bring design thinking approaches to the forefront.

Incorporating Understanding by Design and Universal Design for Learning

Prioritizing Understanding by Design (UbD) and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) and the two non-negotiable factors—course quality and student satisfaction—played a paramount role in optimizing the unit’s workflow, design considerations and the efficient use of available resources. Undeniably, efforts were geared towards sustainability versus merely serving the call for ERT. Hence, it was essential to continue to base design thinking practices on established UbD and UDL frameworks.

UbD or Backward Design brings efficiency to the course design process, where desired learning objectives are first determined, followed by assessments or evidences to confirm learning has happened. Finally, course materials and activities necessary to meet the objectives are planned (Wiggins & McTighe, 2012). The UbD framework prioritizes and stresses the intentionality of these course components. Courses based on UbD have a proven positive impact on both student learning and motivation (Hodaeian & Biria, 2015).

IDs helped instructors incorporate UbD into the design process to ensure that course components are well-structured, aligned, and adhere to higher standards of quality and student success. Although, a complete overhaul and redesign of the incoming courses was not feasible given the limited transition timeline, employing UbD entailed:

-

Adapting existing course learning objectives

-

Revising assessments to align with learning objectives

-

Facilitating the creation of new learning activities and materials needed to foster student engagement

-

Incorporating prior student feedback to enhance learning assessments, activities, and facilitation and use of the learning platform

Like UbD, the UDL goal-based framework was kept in mind throughout the course design process, and was never an afterthought. Based on three main active learning networks: recognition, strategic, and affective learning (Rose & Meyer, 2002; Meyer et al., 2014), UDL is guided by three principles: Representation which ensures information is inclusive and accessible to all; Action and expression to allow students to demonstrate what they have learned; Engagement which motivates and empowers students by making information relevant to their needs. Prior to UDL, the burden to adapt to course materials was on the student. UDL transfers that burden back to the course, where instructors are expected to be intentional about creating inclusive ways for students to access information and resources, demonstrate their development, and play a lead role in their mastery and success.

IDs modeled these techniques in design collaboration with instructors to communicate the “what,” “how,” and “why” of implementing UDL for student success. Time constraints pressed IDs to focus on implementing the following essentials of UDL in partnership with instructors:

-

Representation: creating inclusive and accessible course materials

-

Utilized built-in style features and functions within word processing tools, i.e., style headings, color contrast, alternate texts and descriptions for images

-

added features for closed captioning to multimedia content

-

-

Action and expression: offered multiple submission options, such as audio, video, and text, e.g., student introduction posts

-

Engagement: explicitly outlined course outcomes and expectations, detailing instructions for assessment and deadlines

For designer and instructor, UbD and UDL become best practices and part of the fabric of online course design. For students, UbD and UDL attribute to inclusive design and accessibility to information. Students begin to self-monitor performance and practice in learning, which in turn, can lead to active engagement and increased autonomy.

5 Adapted Course Development during Covid

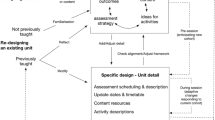

The goal of providing a high-quality educational engagement to learners continued during the preparation of the courses during COVID-19. The team quickly identified an efficient production phase (Fig. 10.1) to channelize their energies, specifically focusing on four vital aspects during the 10–12 weeks of abbreviated development time: supporting course organization, creating effective online learning materials, identifying and designing engaging interactions, and adapting the assessments. These aspects help make the courses sustainable and have the most impact on student learning success in the following manner:

-

1.

Supporting course organization based on Quality Matters, ease of use and navigation in the Canvas LMS

-

Consistent navigation; modular course structure

-

Consistent home page design with links to course orientation materials

-

-

2.

Creating effective online learning materials

-

Shorter video lectures of approximately 10-min segments

-

Providing videos with captions/transcripts; Accessible course documents

-

-

3.

Identifying and promoting methods for student interaction and engagement

-

Regular announcements within Canvas LMS consisting of reminders, course updates, feedback and positive reinforcements

-

Consistent communication guidelines and response times

-

Regular optional/flexible online meeting hours

-

-

4.

Adapting assessments given limited on-campus resources

-

Leveraging of Canvas LMS tools

-

Multiple low-stake formative assessments

-

Communication related to academic dishonesty

-

Grade distribution over multiple assessments

-

The following assurances helped make the process seamless for novice online instructors:

-

Meeting regularly one-on-one with the instructors

-

Creating a project timeline and identifying tangible goals

-

Providing hands-on training in video production

-

Communicating class management strategies

-

Adapting the design template to suit the needs of the course

-

Educating instructors on online teaching and learning best practices and guidelines

6 Artifacts—Survival Kit

To optimize the workflow as IDs worked with the additional course load, several tools, already available in the unit’s arsenal, became artifacts that the unit relied on as part of the online course design process during COVID-19. They include:

-

1.

Design Support and Services Request Survey

-

2.

Course Creation Template

-

3.

Digital Accessibility Quick Guide

-

4.

Course Design Checklist

-

5.

Continuous Feedback — Course Navigation and Design Survey

Due to the abbreviated timeline, the latter of the five tools—continuous feedback from students—was not directly incorporated into the aforementioned COVID-19 transition courses and workflow. However, student feedback, a core component of UDL and integral to continuous course evaluation, remains a critical design practice in our unit. The first four tools, fundamental to the effective and efficient transition, are described below.

For a timely needs-analysis, the first tool in the kit, a Design Support and Services Request Survey, was deployed and linked within an email invite to the initial design meeting. The survey asks about instructors’ experiences in online teaching and course design and prompts instructors to include additional information in an open-ended field. An efficient analysis ensured that IDs were better prepared for the initial design meeting.

The Course Creation Template, the second tool optimizing the workflow, is based on Quality Matters principles of online course design and the alignment of learning objectives, assessments, and materials and activities. The template was designed by the university’s central unit in teaching and learning. As an online learning design unit, we were encouraged to adapt, modify and update the original template and its relevant components. For instance, as a unit, we retained the orientation module, which included instructor’s contact information, a syllabus and course schedule, course navigation instructions, technology requirements and academic support. Information for COVID-19 support and services was added and language and campus-wide policies in the syllabus were modified. With the tailored Course Creation Template, the unit was to effectively communicate key components of an online course in partnering with instructors. Furthermore, IDs worked with individual instructors to further customize the template to fit student needs. Guidelines and best practices related to lecture recordings, various means and channels of communication with students, and online assessment were shared.

The third and fourth tools, a streamlined Course Design Checklist and Digital Accessibility Quick Guide, were used during the course design process and are based on QM principles and adhere to the WCAG 2.0 (2018) principles. Both checklists were indispensable to the designer-instructor partnership before and during COVID-19.

7 Lessons Learned and Recommendations

Having a holistic view of an emergent situation and re-assessing the parameters effecting the supply-demand cycle to come up with a viable action plan have a much more lasting effect on the end-product. Holding such viewpoints is how the IDs in our online learning design unit persevered.

The unit chose a back to design basics method of survival in pandemic times and continues to base design decisions on time-tested and evidence-based UbD and UDL frameworks. This is critical in helping IDs and instructors alike meet overall goals of sustainable, accessible and learner-centric courses. In a period of confusion and uncertainty, IDs assessed the design cycle and promptly identified where in the production phase to direct energy. Doing so resulted in increased instructor buy-in for adapting meaningful and sustainable online course organization, empathy for creating inclusive learning materials, and building upon assessments that foster valuable learner engagement and success. This was evident as the instructors became more receptive to design practices beyond the initial development phase and as the semester progressed.

The design unit relied on its unwavering application of artifacts. These artifacts are part of the unit’s survival toolkit, comprised of the two checklists, a course design template and need analysis survey and essential to the designer-instructor partnership. Each tool and ID contributed to and ensured that the unit’s limited development time was effectively and efficiently utilized. These tools could be part of any design initiative seeking to create learner-centric engagement and sustainable learning experiences. Understanding instructors’ needs, empathizing with their apprehensions and supporting them in all ways possible during this transition or related endeavor can help alleviate misconceptions about online learning and the role of the instructional designer. The experience described in this chapter fostered open discussion on various aspects of online learning and furthered the goal of an enhanced learning experience for students. The conscious efforts taken by the unit to incorporate and adapt design thinking and empathy at the start of the designer-instructor relationship, are sure to result in building stronger partnerships and, in turn, more robust and learner-centric courses.

References

Ali, W. (2020). Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: A necessity in light of Covid-19 pandemic. Higher Education Studies, 10(3), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v10n3p16

Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

Hodaeian, M., & Biria, R. (2015). The effect of backward design on intermediate EFL learners’ L2 reading comprehension: Focusing on learners’ attitudes. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2(7), 80–93.

Jandrić, P., Hayes, D., Truelove, I., Levinson, P., Mayo, P., Ryberg, T., … Hayes, S. (2020). Teaching in the age of Covid-19. Postdigital Science and Education, 2(3), 1069–1230.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice. CAST Professional Publishing.

Milton, J. (2000). Paradise Lost (pp. 1608–1674). Penguin Books.

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

UNESCO (2020). Covid-19 Educational disruption and response. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2012). Understanding by design, expanded (2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. http://www.ascd.org/publications/books/103055.aspx

W3C World Wide Web Consortium (2018). WCAG 2.0 HTML techniques (URL: https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG20/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Chatterjee, R., Juvale, D., He, L., Evans, L.L. (2022). Back to Design Basics: Reflections, Challenges and Essentials of a Designer’s Survival Kit during a Pandemic. In: Dennen, V., Dickson-Deane, C., Ge, X., Ifenthaler, D., Murthy, S., Richardson, J.C. (eds) Global Perspectives on Educational Innovations for Emergency Situations. Educational Communications and Technology: Issues and Innovations. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99634-5_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-99634-5_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-99633-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-99634-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)