Abstract

This chapter is based on an analysis of Germany’s biggest education-related Twitter hashtag before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. We study the reconfiguration of the central actors and topics along the #twlz hashtag to trace the change in pandemic-related communication about education. Specifically, we focus on two arguments developed by education scholars as responses to the COVID-19 crisis: educational technology providers and political actors increasingly turn to social media to mediate their COVID-19 crisis management; at the same time, educational technologies are increasingly being positioned as solutions to the educational challenges posed by the pandemic. Using an analytical framework of affinity spaces, we extend on the hashtag studies and understand the #twlz hashtag as an ongoing process of associating various actors, topics, and things. Through a mix of qualitative and quantitative analysis, we addressed questions of how educational technology providers and political actors reconfigured the #twlz affinity space and how suitable the concept of affinity space is for studying crisis through Twitter hashtags. We identify shifts in topics and actors central to the #twlz affinity space as a reaction to the national and regional educational crisis management over time and trace the practices through which these shifts unfold. With our empirical investigation of educational Twitter communication as practices of reconfiguration rather than content redistribution, we contribute to new perspectives for critical data studies (in education) conceptually and methodologically.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Digital methods

- Process analysis

- Platform as process

- Education

- COVID-19

- Streamgraph

- Affinity space

- Temporality

- Controversy

Introduction

The ambiguity of data power and related in/securities acquired a new meaning in 2020 as theCOVID-19pandemic gripped our globalised societies. The educational domain was particularly affected by COVID-19 by early lockdowns, a transition to online schooling and eventually hybrid modes of teaching. Educational scholars observed inequalities and transformations taking place in the educational domain (e.g. Black et al., 2020; Selwyn & Jandrić, 2020). A public debate ignited around online teaching, digital learning infrastructures, digital literacy (for both teachers and students), and digital content. As educators in Germany and other countries increasingly use Twitter for professional communication (e.g. Carpenter et al., 2020; Greenhalgh et al., 2020; Staudt Willet, 2019), Twitter became one of the spaces where the educational crisis was publicly discussed during the pandemic. To conceptualise the implications of datafication for education, educational scholars often turn to critical data studies (Breiter & Hepp, 2018; Jarke & Breiter, 2019).

Many scholars have turned to social media such as Twitter or Facebook to study public discourses during times of crisis (e.g. Marres & Moats, 2015). A manifold of digital tools has been developed to support such analysis. In particular, when studying crisis, social media researchers focus on Twitter for “real-time data” on public communication and conduct so-called hashtag studies for disaster and crisis analysis (Bruns & Burgess, 2016, p. 23). In such studies, hashtags associated with a particular disaster or moments of crisis are the point of reference for further analysis. However, as critical data studies scholars have widely argued, (social media) data are performative in relation to the definitions of the phenomena—in this case the crises—they are supposed to merely represent (Crawford & Finn, 2015). For example, at times a disaster (or crisis) is so pervasive in public discourse that users cease to use hashtags ascribed to it, because almost all communication relates to this disaster (Tufekci, 2014).

We take these key insights from critical data studies and apply them to the analysis of Twitter communication. We propose to address the recursive and temporal character of platforms as objects of study (Baygi et al., 2021; Ruppert, 2013; Williamson, 2016) by attending to hashtags not as stabilised networks representing public discourse, but rather, as an unfolding process, a continuous flow of action. We argue that a hashtag is more than the sum of the human actors contributing to a particular topic. Rather hashtags

should be understood not simply as ‘gadgets’ that do things but as complex and unstable assemblages that draw together a diversity of people, things and concepts in the pursuit of particular purposes, aims, and objectives. (Harvey et al., 2013, p. 294)

This “drawing together” through hashtags not only provides a representation of discourse about a crisis, but rather, it performs the crisis in particular ways in that they “generate new attentional flows” (Baygi et al., 2021). In this chapter, we propose to study the education-related discourse on the Corona pandemic not through a Corona-related education hashtag but rather through the study of the unfolding discourse within (and along) an education-related hashtag that serves as an “affinity space” (Gee, 2005) for German educators. Our study is, therefore, different from “hashtag studies” that follow the most popular hashtags emerging in a crisis to explore the dynamics of content (re-)distribution (e.g. Gruzd & Mai, 2020) in that we demonstrate how the analysis of a hashtag as an “affinity space” (Gee, 2005) is well suited to the examination of the unfolding of a crisis across Twitter. Understanding a hashtag as an affinity space—as a learning environment—allows us to attend to the recursivity of social media data by highlighting how the hashtag becomes reconfigured in the wake of and during times of crisis. Affinity spaces are a useful analytical lens through which to study the temporality and unfolding of a “controversy” (Marres & Moats, 2015) and for attending to the attentional flows of its participants.

Our study is based on the hashtag #twitterlehrerzimmer (or #twlz), Germany’s biggest affinity space for educators covering topics such as teachers’ everyday lives, pedagogy, and educational technologies. #twlzFootnote 1 can be translated as “Twitter staff room”, signifying the room in which teachers meet in between classes and find time to update each other on important school-related matters or simply chat among themselves. Among the #twlz hashtag users are not only teachers but also the general public, collectives, and commercial organisations from the educational domain, as well as scholars, parents, and some pupils. Some of the #twlz users occupy multiple roles. We collected tweets related to the #twlz hashtag from November 2019 until the start of the summer holidays in mid-July 2020. A mixed-method explorative approach, including data science methods and qualitative content analysis, was applied to the dataset.

We examine our dataset in regard to two arguments developed by education scholars as responses to the COVID-19 crisis: (1) educational technology (ed tech) providers and political actors increasingly use social media to mediate their COVID-19crisis management; (2) at the same time, educational technologies are being increasingly positioned as solutions to the educational challenges posed by the pandemic (e.g. Johns, 2020; Selwyn, 2020; Teräs et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2020). Starting with these arguments, we ask (1) how have ed tech providers and political actors reconfigured communication via #twlz on Twitter and (2) how suitable is the concept of affinity space for studying controversies in times of crisis through Twitter hashtags.

In the following, we first provide an account of work related to the study of Twitter communication in times of crisis. Subsequently, we introduce the context in which our study took place and provide a timeline of education-related events during the COVID-19 crisis in Germany as well as results of studies considering the impact of ed tech providers and political actors on education. In the next section, we present our case study and research design. Subsequently, we identify shifts in the topics and actors mentioned in tweets and retweets in the #twlz affinity space as a reaction to the national and regional educational crisis management over time. Finally, we reflect on how the concept of affinity spaces contributes to new perspectives in critical data studies on three levels: conceptually, methodologically, and to critical data studies in education.

Analysing Twitter in Times of Crisis

Educators’ Twitter use has been examined by educational researchers from a variety of perspectives: the professional development of teachers (Britt & Paulus, 2016; Carpenter & Krutka, 2014; Visser et al., 2014) and school leaders (Sauers & Richardson, 2015), education activism (Thapliyal, 2018), and Twitter’s role in teaching practices (Tang & Hew, 2017). Methodologically, earlier studies of educators’ Twitter practices were based on self-reports in surveys (see Tang & Hew, 2017), while later studies focus on the data available through Twitter platform affordances such as account information (Kimmons et al., 2018) or specific education-related hashtags. Most educational hashtags are specific to a language and/or region (Greenhalgh et al., 2020). Through hashtags, educators share experiences and resources based on their geographical (Carpenter et al., 2020) or subject-related (Larsen & Parrish, 2019) interests. Educational stakeholders (e.g. teachers, public administration, and ed tech providers) use hashtags to communicate their diverging interests about topics such as digital education and to, varying degrees, collaborate.

Studying various stakeholder groups on Twitter, boyd (2010) proposed to approach spaces and collectives emerging through social media as “networked publics”, a rather stable set of actors embedded in a similarly stable space, the social media infrastructure. The notion of (networked) publics can cover a great variety of human actors, connected either tightly or loosely based on their common identities, endeavours, and practices (ibid.). Despite being sensitive to the platform affordances, publics as an analytical concept delineates people (social media users) from the infrastructural and material properties of the space where they communicate, primarily focusing on content production and consumption. The tweets, retweets, likes, and replies can be understood as redistribution practices, allowing for the circulation of content and increasing the visibility of popular topics (e.g. Theocharis et al., 2015, p. 205).

However, as studies into educational Twitter communication have shown (e.g. Carpenter et al., 2020), hashtags such as #twlz not only serve to redistribute content but to also facilitate the interactions between users and enhance mutual learning. It is for this reason that some scholars have argued that social media and educational hashtags specifically should be understood as communities (see e.g. Britt & Paulus, 2016). For example, teachers can be described as a “community of practice” (Lave & Wenger, 1991). The #twlz hashtag serves as a space in which community members learn about and discuss education-related matters. However, in hashtags studies, relying on the concept of “belonging” to a hashtag community is challenging; hashtag studies need to include people who use hashtags passively, stop using hashtags as they become “obvious” to others, or change hashtags used to describe phenomena over time (Baygi et al., 2021; Tufekci, 2014).

To circumvent that challenge, we propose that contributors to hashtags such as #twlz do not form a community or a “networked public”, but rather, they create an “affinity space” (Gee, 2005). The membership in an affinity space is not defined by (institutional) boundaries as is the case for teachers meeting in a school’s staff room, but through the performance of platform-specific ways of interacting and is not restricted to tightly connected actors; rather, the space allows for different kinds of participation. Platform-specific dynamics and affordances in the affinity space can be approached first as varying resources, skills, and forms of participation available to different actors (e.g. differences between Twitter accounts used privately or by organisations or diverging access to further information beyond social media sites). Second, affinity spaces can be accessed through “portals” (Gee, 2005, p. 226), which do not simply open the spaces for new participants, but rather co-produce the resulting spaces, for example, learning from each other. Finally, affinity spaces illustrate the recursive character of social media (data), as the notions of internal and external “grammar”—the organisation of the elements and practices in an affinity space—suggest mutual transformation (ibid., p. 226).

In the case of the #twlz as an affinity space, we observe how users change and create new hashtags or use @-mentions to invite specific accounts, thus shifting over time both the common endeavours and the sets of actors. It is in this way that attending to hashtags as purposefully created entry points to a particular space and a flow of action, we stay sensitive to the challenges of Twitter and particularly hashtag research. We extend on the work of Marres and Gerlitz (2016) in that our starting point is an affinity space through which we aim to understand the dynamics of the problematisation (Callon et al., 1983) of the COVID-19 pandemic for German education. For example, we demonstrate what can be gained by attending to the temporality and the changing dynamics of hashtag and topic authorship rather than the shifting frequency of hashtags. We make an analytical move away from studying the differences between hashtags as several stabilised networks of topics and actors. By investigating processes of reconfiguration and establishing how the #twlz affinity space emerges and unfolds in a time of crisis we contribute to the new perspectives to critical data studies.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and German Education in Context

Education in Germany is run by the federal states (Laender). This means that there is no coherent national strategy, but rather different approaches across the 16 Laender. States’ Ministries of Education were responsible for educational crisis management and governance as the COVID-19 pandemic began to take hold. The 16 Education Ministers build a Standing Conference of the Ministers of Education and Cultural Affairs of the Laender of Germany which enables exchange and results in multilateral agreements. An exception from the Laender-led educational politics represents the so-called DigitalPakt Schule. This national funding programme passed in April 2019 in accordance with the Federal Department of Education and the 16 Laender and was designed to provide 5 billion Euros to cover school districts’ digital infrastructure expenses. During the COVID-19 pandemic, additional funds have been made available within the “DigitalPakt Schule” scheme to support content and infrastructure development for remote teaching and learning. In the early days of the pandemic, many school districts were still preparing their funding applications and by the time of the first lockdown they were left without the necessary ICT equipment. Twitter communication surrounding digital education both before and during the pandemic has been tightly entangled with political topics such as the “DigitalPakt Schule” scheme. Moreover, while some political actors such as the Ministries of Education of the Laender have served as ed tech providers, local school districts have been responsible for maintenance and technical support.

To be able to contextualise our analysis of the #twlz affinity space, we developed an education-related COVID-19 timeline of events in Germany (Table 1). It covers the events related to the recognition of the COVID-19 crisis and the national and regional measures taken in Germany with particular focus on educational crisis management. Overall, the educational domain has not received much attention from political actors. However, the political debates and the actions that followed around school reopenings in spring 2020 generated strong opposition from educators and other stakeholders. In North-Rhine Westphalia (short NRW) the lack of straightforward communication between the responsible ministry of education and schools resulted in appeals (and hashtags such as #schulboykotnrw—school boycott NRW) in and beyond the #twlz affinity space to boycott school openings, followed by an official clarification of the situation by the state’s premier of the federal state. In the context of remote and hybrid schooling, affinity spaces such as #twlz, already used for the exchange of information and resources among educators before the pandemic, acquired additional significance for a broad swathe of actors in the educational domain. As we will demonstrate in what follows, certain actors addressed the #twlz hashtag much more frequently during the pandemic than before as new topics emerged.

Educational researchers have analysed the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for education within and across different countries. One focus was on ed tech providers’ communication and self-presentation (Selwyn, 2020; Teräs et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2020). Many companies offering ed tech provided their services during the pandemic “for free” while continuing to collect data and pushing towards a longer-term transition to digital learning. Another group that also receives scholarly attention in reflections on the pandemic are political actors. Questions rise about the ways in which political actors (and governments) are engaged in publicly mediating their COVID-19 crisis management differently with many increasingly turning to digital media to communicate with various stakeholders (Johns, 2020). Through our analysis, we explore whether and how the #twlz affinity space reflects these reports in the German context. To do so we trace how the COVID-19 pandemic is problematised in one education-related affinity space and how that, in turn, reconfigured that space.

Case Study and Research Design

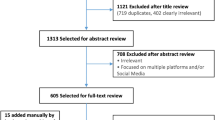

The history of the hashtag #twlz goes back (at least) seven years. Our analysis covers the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic and spans the period beginning 10 November 2019 until the start of the school summer holidays on 31 July 2020. We used the free Twitter streaming API to collect tweets and retweets including one of the selected hashtags #twitterlehrerzimmer, #twlz, #edchatde (historically the earliest German education-related hashtag, later superseded by #twlz). Replies and other (possibly relevant) tweets which did not use any of the listed hashtags were not included in the dataset and subsequent analysis. In total, we collected 131,394 individual posts (39,011 tweets and 92,383 retweets). Around 25,003 accounts participated in the #twlz affinity space. Bots, deleted, or blocked accounts were excluded from the analysis. By participation, we understand both producing tweets and retweets, but also being introduced to the affinity space by others through the Twitter @-mention functionality. Applying the framework of affinity space, we understand @-mentions as “portals” that open and reconfigure the #twlz affinity space. Examining the mentioned accounts enables us to identify how shifts in the affinity space emerge as a reaction to the pandemic and its crisis management over time. We manually coded all user accounts belonging to those who participated in the affinity space more than three times (N=5840) to assign them to an inductively generated actor group. Following previous pandemic-related educational research, we, too, mainly focus on two actor groups in this chapter: ed tech providers (N=218) and political actors (N=323). Moreover, both groups experienced a rise in participation in the #twlz affinity space during the COVID-19 pandemic. The accounts that participated through tweets or @-mentions less than three times that we did not analyse made up the majority (“long tail”) of accounts in the affinity space.

In total, the users generated both with their tweets and retweets 13,749 additional hashtags to the ones we had identified for collection (#twlz, #twitterlehrerzimmer). To determine hashtag-based topics, we manually compiled hashtags used 25 times or more (N=1134) in the dataset into 14 distinctive, inductively generated topics of varying size and complexity. In approaching these topics, we aimed to trace the shifts in the dynamics of problematisation. Certainly, our personal and professional backgrounds as German-based researchers at different stages of our careers, living in differing family contexts, and our research interest in datafied education were performative to the resulting list of topics (for the detailed discussion on the performative agency of the data scientists and interpreter, see e.g. D’Ignazio & Klein, 2020). Studying Twitter datasets is related to a number of challenges: the opaque Twitter API algorithm (Bruns & Burgess, 2016, pp. 21–22); the challenges of differentiation between studies of users activities on Twitter, platform affordances, and sociality in general (see also Marres & Gerlitz, 2016); focus on active tweeters; and a wide range of ethical challenges. For example, we encountered some accounts (N = 406) to which we could often clearly assign a particular actor group despite the user’s statement in their bio about tweeting “privately” with this account. Simply by using a hashtag on Twitter, users cannot foresee research that uses the platform where their Tweets may be included as part of a larger dataset. We primarily focused, therefore, on aggregated data. Usually when a study is not centred around a content analysis of Tweets and instead focuses on hashtag-based topics, as we did, the next step should be to interview users and make their voices heard in the research process. This circumvents the challenge of carrying out research and talking about people rather than with them.

#twlz as an Affinity Space

#twlz has no specific local boundaries, although it mostly covers German issues and, therefore, German users while there is also a relatively small number of users from other German-speaking countries. Both before and during the pandemic, the hashtag #twlz was promoted by some pioneer educators (see, in regard to pioneer communities, Hepp, 2016) on Twitter and their personal websites, blogs, vlogs, or podcasts and even by a number of commercial educational companies. Many of the active #twlz contributors are engaged in educators’ professional development as facilitators at the local and regional level, particularly in the domain of educational media and technology. These groups accounted for up to 39 per cent of the accounts we analysed. Respectively, the most frequently used hashtag was #digitalebildung (digital education); it was used 7082 times across the whole dataset. Before the pandemic and over the first few months of the COVID-19 crisis digital education was a core hashtag (and topic) within the #twlz affinity space and directed us to the starting point of our analysis. The digital education hashtag and those similar to it (e.g. #zeitgemäßebildung—contemporary education or #digitalesklassenzimmer—digital classroom) both attend to the educational technologies required for providing “contemporary” teaching and imply a political appeal about perceptions of what constitutes quality school education. Besides educators actively using the #twlz affinity space, the hashtag was able to bring in political actors and the subject of educational technologies (and their providers).

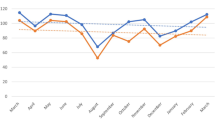

For the purpose of our analysis, we divided the dataset into two periods of varying length: pre-crisis—which marked the first part of our data collection from 10 November 2019 until 5 March 2020—and during the crisis period until the end of our data collection 31 July 2020. The most active group throughout the whole period were educators (which is not surprising given the affinity space we researched, see Fig. 1). The two actor groups experiencing a rather continuous participation boost were political actors and ed tech providers, even though both groups were among the least present in the #twlz affinity space. The other actors who were not included in the manual coding process (because they participated only one or two times in the #twlz hashtag discourse) make up the second biggest group contributing to the #twlz affinity space. However, these actors were much more actively retweeting #twlz-related content and, therefore, can be considered as observers rather than drivers of the discussion. The charts below illustrate how our manual coding covered the majority of actors creating original tweets with the #twlz hashtag and thus constitute the #twlz affinity space to the widest extent.

Different actor groups’ tweeting (above) and retweeting (below) activities over time. The vertical axis shows the number of tweets and retweets generated daily by each actor group. The horizontal axis shows the COVID-19 and #twlz timeline’s overlaid. Numbers indicate the rows of Table 1

Shifting from an analysis of frequency to one of the dynamics of problematisation, we proceeded with our analysis by examining the topics the identified actor groups discussed before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 2 illustrates 14 topics that emerged through manual coding and the remaining/unsorted hashtags grouped together. Any tweet or retweet may have included more than one hashtag; therefore, the number of hashtags used in the #twlz affinity space differs from the number of tweets and retweets produced in the same affinity space over the course of data collection. The topic concerning educational technologies received much more attention since the beginning of the pandemic both in tweets and in retweets (Fig. 2). By contrast to topics addressed in original tweets, retweets since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic were dominated by COVID-19-related issues, followed by topics such as digitaleducation or general topics in education. During the pandemic, the #twlz affinity space opened up to new actors, possibly from “outside” the educational domain. As the topics (re)tweeted by these accounts suggest, they were concerned with the state of German education during the pandemic and shared the information they came across in the #twlz affinity space with their personal Twitter networks.

Development of the #twlz topics over time in tweets (above) and retweets (below). The vertical axis shows the number of hashtags used in tweets and retweets. The horizontal axis shows the COVID-19 and #twlz timeline’s overlaid. Numbers indicate the rows of Table 1

In our analysis of the affinity space before and during COVID-19, we now turn to two actor groups, which experienced a boost in their participation: political actors and ed tech providers. We are interested in understanding the extent to which the dynamics of problematisation during COVID-19, as observed by other scholars during the pandemic, are visible in the #twlz affinity space.

Educational Technologies and Their Providers in #twlz

The first issue we examined through our dataset concerned ed tech providers and their role in the #twlz affinity space. In our analysis, ed tech providers constituted one of the smallest actor groups participating in the affinity space both before and during the pandemic. Among the reasons for the small number of ed tech providers in the affinity space may be the particularities of the German market, state ed tech providers (Laender), strong legal regulations (e.g. data protection, privacy), big stakeholders among educational media providers, also supported through strong regulation (e.g. accreditation of textbooks). Even though we could observe a growing number of tweets by ed tech providers, in general, their participation in #twlz communication remained lower than that of other actor groups (see Fig. 1). In contrast to the ed tech providers’ accounts, hashtags and topics relating to educational technologies experienced a gradual growth not only in the general peaks of #twlz communication activity, but until the beginning of the summer holidays (Fig. 2). These hashtags can be seen as entry points to the #twlz affinity space, where all interested actors could exchange and build their knowledge about specific software or hardware. According to the topics used in the twlz affinity space referring to educational technologies, we assume that at least before the pandemic, the #twlz users were mostly interested in the expertise and knowledge of educators and facilitators, that is, those who knew how to support teaching and learning processes with educational technologies with the hindsight of the #twlz core topic, digital education. However, during the pandemic, both the number of educational technologies and the methods of their application altered through the practices of remote and hybrid teaching and learning. Through ed tech-related hashtags, actors from “outside” the educational domain could enter the affinity space to contribute with their experiences of, for example, video conferencing or remote team communication and organisation.

To examine these dynamics further, we focused on the educational technologies issue and identified, after an additional round of qualitative coding, four sub-topics: hashtags related to ed tech providers, learning apps, technologies appropriated for education, and hardware. The sub-topic ed tech providers included 59 hashtags ranging from solutions offered by Microsoft (e.g. teamsedu) to solutions offered by companies such as itslearning!—an international learning management system used by a number of Laender—or solutions developed by the states themselves such as LogineoNRW (a learning management system used in one of the Laender). The sub-topic learning apps included hashtags for apps that have been genuinely developed for learning (such as the reading app Antolin). The sub-topic technology appropriated for educationincluded all those hashtags that refer to technologies that had not been developed for educational settings originally but came to be appropriated as tools for (social) learning (e.g. Padlet, Twitch, YouTube). Diverse actors, including the media, ed tech providers, and educational associations used hashtags related to the technologies appropriated for learning more often during the pandemic. Remarkably, since 6 March, ed tech providers alongside educational content providers increasingly tweeted, not only about their own products, but also about other technologies appropriated for education. With the aim of maintaining a high demand for the educational products brought about by remote teaching and learning, technology providers and educational content publishers may have an interest in partnerships with bigger technology corporations (such as YouTube and other streaming platforms).

With this investigation, we were interested in whether the #twlz affinity space was increasingly focused on by the ed tech providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our analysis shows that pioneering educators were not increasingly “targeted” by ed tech providers via Twitter in their “own” affinity space #twlz. These data contrast, then, with the claim that ed tech providers increased their online activity during the pandemic. This increased activity may be observed in other communication spaces on Twitter (e.g. other associated hashtags and affinity spaces) and beyond (e.g. direct communication with educational decision makers). A further content analysis of tweets is required in order to investigate the extent to which educators and other #twlz users attended to the pedagogical and didactic issues of digital technologies in their tweets with ed tech-related hashtags. Observing how ed tech-related topics shifted during the pandemic and how other actors became involved in the knowledge exchange with educators, we notice how digital technologies became a particularly distinct part of the initially central topic of “digital education”. Approaching #twlz as an affinity space renders visible the ways in which hashtags related to digital (educational) technologies facilitate learning about these technologies among different actor groups. The analytical lens of the affinity space allows attendance to other hashtags and not just those most frequently used and tracing how these become more important and reconfigure the affinity space over time.

The Quest for Dialogue with Political Actors

The second argument we explored in our dataset is about political actors’ crisis mediation in their acts of public communication. Results from current scholarly work (e.g. Johns, 2020) are similar to what we observe in the German educational domain. Public administrations acted as facilitators in public events dedicated to digital education and schooling, not least within the “DigitalPakt Schule” funding programme. Recent examples include the “#WirVsVirus” hackathon initiated by the German government or other education-related events such as an online barcamp “#DIGITALITAET20”, organised under the auspices of the Federal Government Commissioner for Digital Affairs. Others included the hackathon, “wirfuerschule” organised by the volunteers from the educational community and initiated under the patronage of the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and other public education organisations. Both hackathons were conceived as a crowd-sourced solution to the challenges posed to the education sector by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many of the national and regional political actors and organisations have had Twitter accounts since before the pandemic; however, they were not a part nor had they even been on the margins of the #twlz affinity space at the time. The epidemiological and political insecurities brought about with the spread of the virus demanded speedy reactions to and communication centred around the changing circumstances and the details of COVID-19crisis management. Even though our dataset includes different time spans pre- and post-pandemic—around four and five months respectively—we assume that the growth in the amount of political actors’ participation illustrates how #twlz became a space for mediating educational politics during the crisis. Politicians and federal or Laender ministries were addressed by other actor groups in the #twlz affinity space more often during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 2). The disparity between the number of political actors being mentioned by other #twlz users and themselves tweeting actively before the pandemic also indicates a continuous quest for dialogue with educational policymakers.

The scatter plot in Fig. 3 maps political actors according to the frequency of their participation in the #twlz affinity space actively (tweeting) or passively (@-mentions). Overall, the Laender Ministries of Education and the Federal Ministry of Education (account names in red) were mentioned more often than they themselves used the #twlz hashtag. Some of them however, engaged with the affinity space (e.g. the Federal Ministry of Education). Politicians such as the Federal Minister of Education or the state premier of NRW (account names in black with the “*”-symbol) were mentioned relatively often. However, they did not directly engage with the affinity space. Most political actors (light grey dots), however, only played a marginal role in the communication that took place in the affinity space. The differences between public accounts and the organisational accounts of political actors and the individual Twitter accounts of educators and other stakeholders are notable if we consider the distribution of resources in the affinity space. Political actors have (access to) different resources than educators and other #twlz users, both in regard to the maintenance work required to sustain a Twitter account and the skills of professional social media content creators. Despite lacking access to these resources, educators and other groups reached out to politicians much more often and created additional entry points to the affinity space through Twitter affordances such as @-mentions.

With the development of the COVID-19 pandemic and the necessity to communicate prevention strategies, that quest became ever more important for educators and other actors including politicians and political organisations themselves. The educators and other actor groups were addressing politicians and political organisations predominantly with political topics, presumably reacting to the rapid changes in political strategies. On the other hand, political actors turned most often to the topics covering general topics in education and COVID-19 related hashtags during the pandemic (Fig. 4). Political actors were using political hashtags as well, however at different times than the other actor groups addressed their political appeals to policymakers. This leads us to observe how political actors attempt to “change the subject” (and shift the dynamics of problematisation) of their COVID-19 related communication and pursue their own strategies in the educational crisis mediation on Twitter. Our findings show that political actors problematise the pandemic-related educational crisis differently to other actor groups within the #twlz affinity space, despite the #twlz users’ attempts to introduce the political actors to their discussions. In sum, an analysis of #twlz as an affinity space directs our attention not to the stabilised network of actors, but rather to the reconfigurations brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the introduction of a greater number of political actors into the affinity space, and to the dynamics of problematisation of pandemic-related topics.

Political actors in relation to topics. Topics co-occurring with @mentions of federal (above) and state (middle) political actors over time. Political actors’ contributions to all topics in their original tweets over time (below). Numbers on the horizontal axis indicate the rows of Table 1. Y-axes are aligned with the numbers of hashtags used, which differ among the graphs

Towards a Process View in Critical Data Studies

Critical data studies have developed various theoretical and methodological tools that help to make sense and disentangle the complex relationships of human agency, platform affordances, and corporate interests intertwined in digital data and software. Following changes in affinity spaces over time provides an attractive theoretical and methodological perspective for critical data studies, enabling a processual analysis of platforms. This approach allows for the observation of affinity spaces and how they are being configured while eschewing a “bird’s eye” view on social media communication as a sequence of stable states enacted by a well-defined group of actors. Dynamic, temporal changes in affinity spaces illustrate not only the stabilisations of platform communication but also how and why these stabilisations come to be over time. Overall, our chapter contributes to new perspectives in critical data studies in the three ways: (1) conceptually, we reflect on the dynamic configuration of affinity spaces as an analytical lens for critical data studies; (2) methodologically, we reflect on the ways in which the temporality of a platform can be “captured”; and (3) thematically, we reflect on how our analysis contributes to critical data studies in education.

Approaching affinity spaces as processes of their reconfiguration over time contributes conceptually to critical data studies, as it circumvents some common critique of other approaches—for example, actor-network theory (see, for extensive critical analysis, Couldry, 2020)—such as its “flatness” and little attention to the intentions of human agency. Affinity spaces preserve the focus on the intentionality (as well as identities, knowledge, and values) of human actors and the practices of their ongoing reciprocal learning, driving the dynamics of problematisation forward and enacting change over time. Moreover, similar to the theoretical approach of controversy mapping (e.g. Marres & Moats, 2015), affinity spaces-based analysis allows for the circumvention of the focus on multiple, but seemingly stable networks and instead guides our attention to the practices and temporalities of problematisation and its subsequent stabilisations, staying sensitive to the platform-specific dynamics and affordances. The identification of particular non-human actors (e.g. @-mentions or hashtags) as entry points to affinity spaces makes a conceptualisation of their agency more accessible. Applying the framework of affinity space to a hashtag study such as ours renders visible the ways of configuring the affinity space that drive changes in a recursive relationship between the events, people, issues, and topics that come to be associated in the affinity space.

Methodologically, the attention to the affinity space #twlz is very different to hashtag studies (of crisis communication) that usually tend to pick those hashtags describing the crisis or most visible content. For example, in our dataset a long list of hashtags was related not to education but to COVID-19 (e.g. #COVID2019, #coronavirus), to the lockdown (e.g. #stayhomechallenge, #shutdowngermany, #onlineteaching), and to the “new normal” (e.g. #hybridkonzepte, #lernentrotzcorona, #hybridunterricht). We argue here that rather than attending to these hashtags that are symptomatic during a time of crisis, we should turn to an affinity space (such as #twlz) and study its dynamics of problematisation. This means that we need to find ways to depict and study the process in which a problematisation of the crisis takes place. Hence, rather than depicting stabilised networks of such an affinity space, we are interested in the unfolding dynamics that constitute it. Computational methods and dynamic visualisations of empirical data over longer periods of time enable us to illustrate the breakdowns and frictions, signifying changes in the dynamics of problematisation. Currently, a number of new methodological approaches within critical data studies and beyond are being developed that enact a temporal understanding of data. For example, Bates et al. (2016) propose data journeys as a methodological tool to follow the data movements and frictions within organisations. Baygi et al. (2021) encourage us to “re-orientat[e] our theoretical gaze from spatial relationality to the temporal qualities, conditionalities, and directionalities of flows of action”. Such approaches draw on a variety of data retraction and processing methods as well as on new ways of data visualisation. Affinity spaces as a methodological tool contribute to that rapidly emerging academic discourse.

Our findings contribute to critical data studies in education. We show that the dynamics of problematisation in times of crisis can be examined by attending to the changing reconfigurations of affinity spaces. At the beginning of our analysis, we identified the topic of digital education as central to the #twlz affinity space. At that point, both political actors and ed tech providers were participating in the affinity space, however, following different interests, for example, coupled with the political endeavour to provide national funding as a part of the “DigitalPakt Schule” funding scheme. This funding scheme is obviously highly relevant for both actor groups: for political reception and for businesses. However, as the virus spread all over the world, not only the new modes of teaching and learning, but also new modes of coping with the pandemic were required. During the pandemic, the main topics picked up on Twitter covered COVID-19, lockdown, and post-lockdown related hashtags, reconfiguring educational communication to the challenges of the present crisis. Through the lens of the affinity spaces, however, we identified further topics and dynamics of problematisation. We could show the growing role of political actors, who were directly invited (through @-mentions) to enter a direct dialogue with other #twlz contributors. In the case of educational technologies, no dialogue with technology providers was expected. Instead, a variety of technology-related hashtags served as points of access to the spaces where educators, parents, students, and other actors exchanged their new knowledge and resources.

With our empirical examination of #twlz hashtag-related communication, we were primarily interested in how educational actors conceptualise and problematise the COVID-19 pandemic and reconfigure the affinity space in which the (re-)negotiation of the educational crisis happens and is linked to technological solutions. Overall, our empirical study of the #twlz as an affinity space contributes to the new perspectives of critical data studies as we attend to the #twlz hashtag not as a sum of keywords with which actors describe a topic. It is, rather, a continuous practice of associating actors, topics, and things through which the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for the German educational domain are problematised. Future cross-platform research needs to address the #twlz affinity space in the broader context of public media discourses about the role of education in times of crisis, an in-depth content analysis of tweets (and media coverage) is required to understand these dynamics and the role of data therein.

Notes

- 1.

To improve the readability for non-German-speaking readers, we will use the shorter version of the hashtag throughout the text.

References

Bates, J., Lin, Y.-W., & Goodale, P. (2016). Data journeys: Capturing the socio-material constitution of data objects and flows. Big Data & Society, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951716654502

Baygi, R. M., Introna, L. D., & Hultin, L. (2021). Everything flows: Studying continuous socio-technological transformation in a fluid and dynamic digital world. MIS Quarterly, 45(1). https://aisel.aisnet.org/misq/vol45/iss1/16/

Black, S., Spreen, C. A., & Vally, S. (2020). Education, COVID-19 and care: Social inequality and social relations of value in South Africa and the United States. http://hdl.handle.net/10210/440221

Boyd, D. (2010). Chapter 2: Social network sites and networked publics: Affordances, dynamics and implications. In N. Self & Z. Papacharissi (Eds.), A networked self: Identity, community and culture on social network sites (pp. 39–58). Routledge.

Breiter, A., & Hepp, A. (2018). The complexity of datafication: Putting digital traces in context. In A. Hepp, A. Breiter, & U. Hasebrink (Eds.), Communicative figurations: Transforming communications in times of deep mediatization (pp. 387–405). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65584-0_16

Britt, V. G., & Paulus, T. (2016). “Beyond the Four Walls of My Building”: A case study of #Edchat as a community of practice. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(1), 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2016.1119609

Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2016). Methodological innovation in precarious spaces: The case of Twitter. In H. Snee, C. Hine, Y. Morey, S. Roberts, & H. Watson (Eds.), Digital methods for social science: An interdisciplinary guide to research innovation (pp. 17–33). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137453662_2

Callon, M., Courtial, J.-P., Turner, W. A., & Bauin, S. (1983). From translations to problematic networks: An introduction to co-word analysis. Social Science Information, 22(2), 191–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901883022002003

Carpenter, J. P., & Krutka, D. G. (2014). How and why educators use Twitter: A survey of the field. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2014.925701

Carpenter, J. P., Tani, T., Morrison, S., & Keane, J. (2020). Exploring the landscape of educator professional activity on Twitter: An analysis of 16 education-related Twitter hashtags. Professional Development in Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1752287

Couldry, N. (2020). Recovering critique in an age of datafication. New Media & Society, 22(7), 1135–1151. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820912536

Crawford, K., & Finn, M. (2015). The limits of crisis data: Analytical and ethical challenges of using social and mobile data to understand disasters. GeoJournal, 80(4), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-014-9597-z

D’Ignazio, C., & Klein, F. L. (2020). Seven intersectional feminist principles for equitable and actionable COVID-19 data. Big Data & Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720942544

Gee, J. P. (2005). Semiotic social spaces and affinity spaces: From the age of mythology to today’s schools. In D. Barton & K. Tusting (Eds.), Beyond communities of practice: Language, power, and social context (pp. 214–232). Cambridge University Press.

Greenhalgh, S. P., Rosenberg, J. M., Staudt Willet, K. B., Koehler, M. J., & Akcaoglu, M. (2020). Identifying multiple learning spaces within a single teacher-focused Twitter hashtag. Computers & Education, 148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103809

Gruzd, A., & Mai, P. (2020). Going viral: How a single tweet spawned a COVID-19 conspiracy theory on Twitter. Big Data & Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720938405

Harvey, P., Reeves, M., & Ruppert, E. (2013). Anticipating failure. Journal of Cultural Economy, 6(3), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17530350.2012.739973

Hepp, A. (2016). Pioneer communities: Collective actors in deep mediatisation. Media, Culture & Society, 38(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443716664484

Jarke, J., & Breiter, A. (2019). Editorial: The datafication of education. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2019.1573833

Johns, F. (2020). Counting, countering and claiming the pandemic: Digital practices, players, policies. In L. Taylor, G. Sharma, A. Martin, & S. Jameson (Eds.), Data justice and COVID-19: Global perspectives (pp. 90–99). Meatspace Press.

Kimmons, R., Carpenter, J. P., Veletsianos, G., & Krutka, D. G. (2018). Mining social media divides: An analysis of K-12 U.S. School uses of Twitter. Learning, Media and Technology, 43(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1504791

Larsen, J., & Parrish, C. W. (2019). Community building in the MTBoS: Mathematics educators establishing value in resources exchanged in an online practitioner community. Educational Media International, 56(4), 313–327. Scopus. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2019.1681105

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Marres, N., & Gerlitz, C. (2016). Interface methods: Renegotiating relations between digital social research. STS and Sociology, 64(1), 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12314

Marres, N., & Moats, D. (2015). Mapping controversies with social media: The case for symmetry. Social Media + Society, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115604176

Ruppert, E. (2013). Rethinking empirical social sciences. Dialogues in Human Geography, 3(3), 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820613514321

Sauers, N. J., & Richardson, J. W. (2015). Leading by following: An analysis of how K-12 School leaders use Twitter. NASSP Bulletin, 99(2), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636515583869

Selwyn, N. (2020). Digital education in the aftermath of COVID-19: Critical concerns & hopes. Selwyn, N., Macgilchrist, F., Williamson, B. (eds.). Digital Education After COVID-19. TECHLASH, 1, 6–10.

Selwyn, N., & Jandrić, P. (2020). Postdigital living in the age of COVID-19: Unsettling what we see as possible. Postdigital Science and Education, 2, 989–1005. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00166-9

Staudt Willet, K. B. (2019). Revisiting how and why educators use Twitter: Tweet types and purposes in #Edchat. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 51(3), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2019.1611507

Tang, Y., & Hew, K. F. (2017). Using Twitter for education: Beneficial or simply a waste of time? Computers and Education, 106, 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.12.004

Teräs, M., Suoranta, J., Teräs, H., & Curcher, M. (2020). Post-COVID-19 education and education technology ‘Solutionism’: A seller’s market. Postdigital Science and Education, 2, 863–878. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00164-x

Thapliyal, N. (2018). #Eduresistance: A critical analysis of the role of digital media in collective struggles for public education in the USA. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 16(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2017.1356701

Theocharis, Y., Lowe, W., van Deth, J. W., & García-Albacete, G. (2015). Using Twitter to mobilize protest action: Online mobilization patterns and action repertoires in the Occupy Wall Street, Indignados, and Aganaktismenoi movements. Information, Communication & Society, 18(2), 202–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.948035

Tufekci, Z. (2014). Big questions for social media big data: Representativeness, validity and other methodological pitfalls. In ICWSM ‘14: Proceedings of the 8th International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, 2014. https://arxiv.org/abs/1403.7400

Visser, R. D., Evering, L. C., & Barrett, D. E. (2014). #TwitterforTeachers: The implications of Twitter as a self-directed professional development tool for K–12 teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 396–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2014.925694

Williamson, B. (2016). Digital methodologies of education governance: Pearson plc and the remediation of methods. European Educational Research Journal, 15(1), 34–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904115612485

Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1761641

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted as part of the DATAFIED research project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (project number 01JD1803A). The authors are grateful to the DATAFIED team members Annekatrin Bock, Vito Dabisch, Sigrid Hartong, Sieglinde Jornitz, Angelina Lange, Felicitas Macgilchrist, Ben Mayer, Tjark Raabe, Jasmin Tröger for their crucial feedback and lively discussions. We also thank our student assistants Hendrik Meyer, Maximilian Spliethöver, and Yan Brick.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Zakharova, I., Jarke, J., Breiter, A. (2022). Affinity Spaces as an Analytical Lens for Attending to Temporality in Critical Data Studies: The Case of COVID-19-Related, Educational Twitter Communication. In: Hepp, A., Jarke, J., Kramp, L. (eds) New Perspectives in Critical Data Studies. Transforming Communications – Studies in Cross-Media Research. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96180-0_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96180-0_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-96179-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-96180-0

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)