Abstract

Over the past decade, researchers investigating IT security from a socio-technical perspective have identified the importance of trust and collaboration between different stakeholders in an organisation as the basis for successful defence. Yet, when employees do not follow security rules, many security practitioners attribute this to them being “weak” or “careless”; many employees in turn hide current practices or planned development because they see security as “killjoys” who “come and kill our baby”. Negative language and blaming others for problems are indicators of dysfunctional relationships. We collected a small set of statements from security experts’ about employees to gauge how widespread this blaming is. To understand how employees view IT security staff, we performed a prolific survey with 100 employees (n = 92) from the US & UK, asking them about their perceptions of, and emotions towards, IT security staff. Our findings indicate that security relationships are indeed often dysfunctional. Psychology offers frameworks for identifying relationship and communication flows that are dysfunctional, and a range of interventions for transforming them into functional ones. We present common examples of dysfunctionality, show how organisations can apply those interventions to rebuild trust and collaboration, and establish a positive approach to security in organisations that seizes human potential instead of blaming the human element. We propose Transactional Analysis (TA) and the OLaF questionnaire as measurement tools to assess how organisations deal with error, blame and guilt. We continue to consider possible interventions inspired by therapy such as conditions from individual and group therapy which can be implemented, for example, in security dialogues or the use of humour and clowns.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Human factors in IT security

- IT security awareness

- Dysfunctional relationship

- Socio-technical systems

- Interpersonal communication

- Transactional analysis

- Joint optimisation

1 Introduction

Awareness that the “human element” is an important factor in IT security (ITS) has been growing steadily over the past decades. But to this day, the discourse is dominated by the “weakest link” narrative, originally coined in 2000 by leading security practitioner Bruce Schneier (see Sect. 2.1), which implicitly blames humans as the reason for security problems. As we shall see in Sects. 5, this view shapes academic and industry discourse on human behaviour in security, and means that most solutions aim to somehow “fix” defective humans. The assumption that this is the way to improve security is ingrained into ITS practice in organisations, who run awareness campaigns reminding employees of organisational policies, and attacking employees through simulated phishing campaigns in the name of training. On the other hand, there is a growing recognition for the need to reconfigure ITS in a positive manner, as the root cause lies in security solutions that are impossible to follow, or conflict with other demands people face – such as productivity [8, 29]. Research has repeatedly shown that most people do care about security, and are willing and able to use security measures that cater for those needs [13]. Research has also shown that most people are willing to contribute to a broader organisational and societal security effort beyond their own needs if their stance towards those entities are mostly positive [10, 21]. The conclusion from socio-technical research very firmly is that

“Trust and collaboration [...] are necessary for effective cybersecurity.” [16]

Beyond security benefits, recent research has shown that in productive and innovative organisation there are three essential factors: employees feel safe, connected to members of the organisation, and believe they have a shared future [17]. Currently, many ITS practices work in exactly the opposite direction – in anti-phishing training, for instance, employees experience being attacked by their own company (or an agent acting for the company), and subsequently don’t feel safe. When they recognise that an anti-phishing campaign is being run, they are told not to inform their colleagues since this would “undermine the effectiveness of the campaign” – and creating the impression that security is something everyone has to do alone, rather than something to be tackled collectively. Finally, “failing” security tests or non-compliance are associated with the threat of sanctions and dismissal – not creating the impression of a long-term future. Relationships between different stakeholders are a long way from trust and collaboration when it comes to security: security experts see employees as stupid and lazy, and feel entitled to demand time and attention from employees “because security is important”. As Herley puts it: “security practitioners treat users’ time as an unlimited resource” [22] and “think we [the security practitioners] can convince people to spend more time on security” [23]. Many organisational leaders don’t engage with how to manage security because they see security as “technical” and leave most decisions to experts; even when they do engage, their focus is often on complying with regulatory requirements, not whether security arrangements are working in practice. Developers hide their ideas for innovations from security staff, because they think their “default setting is NO” and fear “they will come and kill our baby” [4]. Security practitioners are forced to accept security training packages they know to be out-of-date and ineffective by procurement officers who insist they take the cheapest offer. In modern organisations, dysfunctional relationships are everywhere when it comes to security. In this paper, we present a roadmap for organisations looking to work their way back from that brink, and towards a trusting and collaborative culture. We present knowledge and tools for detecting dysfunctional relationships, and interventions for transforming them into working ones. Our approach is an interdisciplinary one, bringing together knowledge and tools from clinical psychology (psychology therapy), organisational psychology, social and cultural anthropology and human centred security.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In Sect. 2 we introduce the different ITS relationships in organisational ITS, the narrative of users as “the weakest link” and indicators of dysfunctional relationships. In Sect. 3 we explain our research method and present our results of in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5 we analyse our data in terms of dysfunctional relationships before introducing our Therapy Framework in Sect. 6 to address the problem of dysfunctional relationships. In Sect. 7 we discuss limitations and conclude.

2 Background

2.1 ITS Relationships in Organisations

Organisations are socio-technical systems, and the effectiveness of ITS measures organisations chose ultimately depends on the behaviour of employees, which in turn is shaped by the interaction of different Communities of Practice (CoP) [48]. CoPs in their various positions and departments, having their own work tasks and needs towards IT and security accordingly. Currently, interactions between communities are unfortunately dominated by value conflicts, distrust, lack of cooperation and hierarchy, or circuits of power [15, 26]. Over the past decades, responsibility for security has increasingly been shifted on the shoulders of employees, often creating value conflicts between their primary working and secondary security tasks – primarily productivity [8, 29]. Policies forbid some behaviours and mandate others, and are “supported” by security awareness and training measures that aim to change employees’ attitudes and behaviour, in other words: “fixing the human”.Footnote 1 Most of these are either developed by security specialists, built on their professional knowledge, or by security awareness providers copying what they consider “best practice”, i.e. what publicly available guidance documents by government or regulators recommend. Most of it is not tested for feasibility or effectiveness – and the resulting experience of not being able to follow what they are told haunted by the deficit construction of users [30] – and are often experienced by employees as fear-inducing [6], overly technical and as putting responsibility and blame on them [10, 44].

IT security professionals have their own CoP whose main, primary task is the security of the organisation.

While their work is mostly seen as technical, it is worth noting that the basis for most of those rules is not scientific, but promotes and copies “best practice” – which should more actually called “common practice” since their effectiveness has rarely been evaluated [24]. ITS research until late 90s was almost exclusive technical – but always contains human elements, as security is played out in socio-technical systems. Today, most security specialists are not trained in dealing with human factors – something Ashenden & Lawrence tried to address with Security Dialogues [4]. Further, this often leads to restrictive security measurements that create value conflicts for other employees, who, in turn, revert to workarounds or practice “shadow security” [29] to be able to pursue their primary goals.

Management sits at the top of organisations, which increasingly rely on digital technologies. With reports about data breaches and attacks, there is growing awareness about the importance of security among this CoP. Due to the nature of their work, management tends to focus on numbers, and sees security as a product you can buy, rather than as a collective process that builds on practices of maintenance and care [32]. This misconception of ITS and the work it entails can lead to miscommunication between management and ITS [5] and the devaluation of security practices, resulting in overworked staff within understaffed departments, which, in turn, negatively affects the security of the organisation. Additionally, management often relies on external security specialists, such as national security agencies, consulting firms and security vendors that often have little to no inside into specific work requirements of the other COPs.

2.2 The Curse of the “Weakest Link”

With increasing user numbers of IT systems, the realisation that human capabilities and limitations need to be considered to keep them functioning gave birth to the disciplines of human-computer interaction (HCI) in the 1980s. HCI provides knowledge and methods for designing technology to “fit” the capabilities and limitations of a specific user population, the tasks they perform with the technology in pursuit of their goals, and the context in which that interaction takes place. Technology that doesn’t fit reduces productivity in organisations, and puts of consumers spending their own money – so by the end of the century, HCI had become firmly embedded in computer science teaching and most development practice. Except computer security, where the idea was that people should do as they are told, because security is important. In 1999, two seminal papers highlighted the consequences of unusable security “Users are not the enemy” [1] and “Why Johnny can’t encrypt” [51]. In 2000, Bruce Schneier introduced the narrative of “the user as weakest link” [47]. This implicitly blames people – a perspective that even most usable security researchers subscribe to: when they can’t or won’t follow expert prescriptions, it is because they are “unmotivated” [51] or “lazy” [45]. Klimburg-Witjes [30] recount how this perspective is pervasive in both academic and practioner events today, and so deeply ingrained that some employees believe it themselves [14]. Whilst initially the focus was on “educating” people ignorant of the threats, increasing technology is used to monitor people and enforce “secure” behaviour, using scare tactics and bullying [46]. There is little reflection that there might be something wrong with the security approach, and the tasks it sets for users, or the experts themselves. Assigning the blame to people works its magic every time we tell it to each other, creating ingroups and outgroups hostile to each other – a situation [1] described and diagnosed as a fatal: the enemy is not the legitimate user, but the attacker out there.

2.3 Indicators of Dysfunctional Relationships

Our aim is to identify and transform dysfunctional relationships between ITS professionals and employees in organisations. Based on research on dysfunctional family relationships, the indicators are outlined in Fig. 1 and backed up by psychological theories and empirical studies ITS in practice from [1, 2, 7, 14, 19, 20, 33, 37, 40, 43, 49, 50, 52]. We propose that security needs therapy in order to cultivate cultures of security that build on collaboration and trust.

3 Method

To find indicators of the dysfunctionality of ITS relationships, we chose a two-fold approach for data gathering: ITS practitioner statements and an employee survey.

ITS Practitioner Statements. We collected indicators on the security professionals’ view on “the human element” by analysing public statements of security awareness vendors, security conferences, security consultant vendors, security news portals and newspapers. We searched for articles, statements, reports and whitepapers that contain one of the following keywords: “Employee”, “Human”, “User”, “Weakest”, “Error” or “Insider”. Selection of the conferences, consultant vendors and newspapers is based on a loose collection of what we see as leading in their respective areas, and the twelve leading security awareness vendors (according to [28]) were chosen. We limited our search to statements not older than 5 years. We aimed to find statements that point towards negative relationships.

Employee Survey. To find out the perspective of employees, we conducted an online survey with open questions. We only accepted pre-screened participants that have English as their first language, are US or UK residents, are currently employed and do not have a student status. Participants answered 12 open questions in total regarding negative and positive attributes and experiences of the relationship with the ITS staff in the organisations of the participants (see Appendix A for the full questionnaire). In a first step, the answers were coded deductively based on the survey questions (e.g. “positive experience”, “negative experience”). In a second step, the answers were coded inductively to categorise emerging themes and patterns.

With this, we got a deeper understanding of the relationship between ITS staff and employees from the employees’ point of view, which is so far rather absent from the discourse.

Relationship Analysis and Therapy Framework. We analysed the data for indicators of dysfunctional relationships, to further identify topics and patterns that indicate the presence of obstacles to the functioning of relationships.

4 Results

4.1 Security Vendor Statements

The URI-sources for all quotations can be found in the Appendix B.

Two industry surveys among security experts performed in 2019 suggest that “IT and security professionals think normal people are just the worst”. From 5,856 experts, 54% believe that the one single most dangerous threat to ITS are employees’ mistakes [39]. In the other survey with 500 experts, 91% are afraid of insider threats and 62% believe that “the biggest security threat comes from well-meaning but negligent end users” [12]. In 2016 Ponemon institute found that 66% of 601 security experts “admit employees are the weakest link in their efforts to create a strong security posture” [27].

Among security consulting companies, blaming employees is common, e.g. in this statement from EY “Insider threats can originate from lack of awareness. For example, employees creating workarounds to technology challenges.” that makes employees responsible for problems raised by non-working technological solutions. It is well established in research that many employees won’t let non-working security measures stop them from performing their primary task [29]. At KPMG an author is directly speaking to security end users in Australia: “YOU are the weakest link: where are we going wrong with cyber security in Australia?”. Such weakest link statements can be found in whitepaper from PwC, Deloitte and Accenture as well. IBM on the other side does identify a relationship problem in teams: “Your employees might not trust you - many times, the relationship between the manager and the workers causes the threats to go undetected.”

As expected, security awareness vendors actively use an image of employees as a defect or risk to security that needs to be fixed with the help of their awareness raising and measuring products. 9 out of 12 analysed vendors use the term “users[/ employees] are the weakest link” as a key term to introduce the problem “human error” in their product description or their case studies and whitepapers. The market leader Know4Be for example states: “More than ever, your users are the weak link in your network security. They need to be trained by an expert like Kevin Mitnick, and after the training stay on their toes, keeping security top of mind.” Some vendors are promoting the idea that organisations should see and handle employees as an active danger, as you can see in Kaspersky’s statement: “The Human Factor in ITS: How Employees are Making Businesses Vulnerable from Within”

The leading ITS conference for ITS practitioners, RSA, has dedicated a complete program to “the human element” in 2020, underlining the importance of employees for a successful security strategy besides any technological solution. A search in the conference library and the webcast offer a diverse image: While employees are sometimes still seen as the weakest link, others tackle this idea and try to convince their readers and listeners that employees are only a threat if other parts of the ITS infrastructure fail. Also the highly technical conference Black Hat has a tradition of employee blaming: “What is the weakest link in today’s enterprise IT defences? End users who violate security policy and are too easily fooled by social engineering attack.” The different ITS and cybercrime magazines and journalistic platforms are all over with articles about “weakest link incidents”, human errors and employee blaming. This view is often provided by journalists in reports, but also by comments from experts. Furthermore, ITS journalists are partially pushing the negative image of humans proactively. Namely in the Ask the CISO podcast the interviewers regularly ask suggestive question like “[...] you know people are the weakest link in the security chain. You can have all the wonderful technologies and layers of Technology security protections in place but ultimately it comes down to the person, right?”.

4.2 Employee Survey Results

Prolific offered us 20,874 eligible participants. We paid £1.35 per participant (£8.1/h), which is slightly more than the prolific average of £7.50/h. From initially 100 participants, 8 were excluded from analysis as they proofed not eligible due to stating to not have any experience with ITS staff, resulting in a sample size of n = 92. Prolific provided us with demographic data. 67 participants were female, 25 male. 86 participants were UK citizens, 6 US citizens. Respondents’ age varied from 19 to 73 years, with an average of 36 years. 64 were employed full-time and 28 part-time. Participants came from diverse fields such as Sales, Transportation, Social Services, Finances, Administration, Health Care, Human Resources, Finances, Education and IT. Due to the different natures of their work, the frequency and kinds of interaction with the ITS department differed widely. We offer a glimpse into our preliminary analysis carried out by one researcher that is still indefinite as we plan to further analyse and contrast our findings. Nonetheless, we present insights into the obstacles and facilitators of the (dys-)functioning of the relationships between ITS staff and other employees.

Helpfulness. The experience of helpfulness of ITS staff can be split into four categories: helpful (to varied degrees) (71), not helpful (18), not able to say due to lack of contact (4) and referring to the overall importance for the organisation (10). The vast majority (71 participants) found ITS staff to be helpful or very helpful, referring to them being knowledgeable and able to protect – employees, their data, systems and the organisation as a whole: “Everything feels secure and safe” (P44). However, many in this group also mentioned their helpfulness was limited by their lack of time to solve issues, not being approachable: “[They are] helpful when I can actually get a hold of them!” (P60) as well as capability to offer explanations, as they use “complicate explanations instead of in lay man’s terms” (P52).

ITS: Tasks and Working Style. Asked what participants thought about the job and tasks of ITS staff, most of them referred to their responsibility to monitor the organisation’s systems, handle “IT Queries” and offer protection to the employees and company: “[they] keep the employees computers safe so we can effectively carry out our work” (P24). Many also considered it their job to provide help, giving advice and educating people: “to provide advice and guidance on how to securely handle data, and educate when things go wrong” (P23). Overall, there was an appreciation of the ITS’s job to be complex and demanding, dealing with lots of different issues, technical as well as human.

Experiences with ITS Staff. Roughly  of our participants (62) stated to never have had a negative experience with ITS staff. The remaining 31 who did report on negative experiences mostly referred to long waiting times, issues in communication and security measures as obstacles to their workflows: “9/10 attempts to get issues sorted have results in having to call back or sort the problem myself, or it has taken a long time on a call to them to get it fixed. Usually they don’t understand the issue to begin with.” (P63).

of our participants (62) stated to never have had a negative experience with ITS staff. The remaining 31 who did report on negative experiences mostly referred to long waiting times, issues in communication and security measures as obstacles to their workflows: “9/10 attempts to get issues sorted have results in having to call back or sort the problem myself, or it has taken a long time on a call to them to get it fixed. Usually they don’t understand the issue to begin with.” (P63).

Communication. The question how understandable communication with ITS staff was experienced yielded a variety of answers, ranging from “not at all” to “very understandable”. Most noticeably, there was a differentiation on the media of communication (e.g. face-to-face, on the phone, via e-mail or fixed templates/digital platforms) impacting the understandability of communication. However, the most important factor was ITS staff’s ability to offer explanations and a shared language. Those who found the communication to be “very understandable” usually also stated that their ITS staff is very good at explaining, refrain from using overly technical language, and offer step-by-step guides and good examples. On the other hand, those who found communication hard to understand complained about using lots of jargon: “they speak in technical details which nobody understands and they don’t try to explain anything” (P61). All in all, 26 participants specifically referred to “IT speak” (P51) as being an obstacle to communication, even when they think of themselves as “IT literate”: “I’d consider myself pretty IT literate as a millennial but I often don’t understand what they mean and neither do my older colleagues.” (P10). This is amplified by the unwillingness of ITS staff to offer explanations: “They do send out communication but it is very IT heavy jargon and is quite difficult to understand. They don’t tend to tone down this type of language even if asked” (P15). Some participants further elaborated on the tone of communication, that they experienced as being talked down to, as e.g. by P51: “I think they see themselves as supportive, but the way they talk to staff, they think that staff are simpletons, because they don’t understand how IT systems work. And we’re talking about doctors and nurses being talked down to here!”

Relationship Between ITS Staff and Employees. We asked several questions regarding the relationship between ITS staff and other employees. First, they should describe their view of the relationship, and then how ITS staff might see it. Further, we asked to elaborate on the positive and negative aspects of that relationship (see Appendix C). Finally, we asked for indicators of how ITS staff might feel about them. We categorised 6 answers as describing a poor or bad relationship. P51 complained about them as “talking in IT-speak”, so they had to “sort it out” for their team members who were “not very computer literate”. P61 described the relationship as “poor”, as “they don’t know/care who I am.” P57 referred to a “constant power struggle between the business needs and that of IT security” and P82 criticised hierarchy: “I feel like I am their servant. That everything I do must be reviewed as if they’re my managers”. The two other participants started to avoid them if they could and instead tried to fix the issues themselves (P63, P91). Overall, most participants described their relationship as good (39), professional (6), friendly (12) and helpful (14). However, only 5 participants stated to have regular contact. 33 participants described the relationship as being distant to non-existent. Out of all participants, 11 described their interaction as being focused on issues and problems, which is underscored by the overall high focus on “helpfulness” which runs throughout the answers in our survey. 10 participants thought they would describe the relationship in negative terms, such as being not IT literate (4), frustrating (4), and demanding (1). P6 felt ITS staff would think that“Likely they have to deal with idiots on a daily basis.” and P87 “That we are a pain in the bum.”

5 Data Analysis – Dysfunctional Relationship

Having presented a short overview of our data, we now analyse them using the aforementioned indicators for dysfunctional relationships. All results and statements presented in this section are a drawn from qualitative text questions, rather than from multiple-choice questions.

High Level of Conflict. Our participants named several sources of conflict in their relationship with ITS staff. The most obvious are in frequent misunderstandings and obstacles in communication due to a lack of shared language. This is highly influenced by ITS staff’s ability to explain the concepts they use to others, as well as by the IT literacy of employees. Another source of conflict are the differing expectations of ITS staff’s tasks as well as a lack of knowledge about employees’ work requirements. Some of the answers indicated that employees feel it is ITS staff’s job to help, assist and support as well as educate on “IT issues”, which is something (most) ITS specialists are not trained to do. Further, it only represents a minor part of their actual workload. On the other hand, lack of knowledge about the working requirements of employees could lead to frustration. Also, this can cause security measurements that negatively affect employees’ workflows. This leads to the next source of conflicts: ITS as an obstacle. While most participants were conscious about its necessity and acknowledged that ITS staff had to adhere to rules and regulations themselves, some of them also experienced ITS as negatively affecting their productivity. One major source of conflict was ITS staff’s (lack of) time and approachability.

Negativity in Communication. Negativity in communication exceeds the difficulty of understanding “IT language”: most participants described the communication as friendly and helpful, still the majority of answers indicate that all communication and interaction between ITS staff centred around problems or issues that needed to be solved, giving a negative touch as baseline to their entire communication. Further, answers signalled that in many cases there was no face-to-face communication at all, and usually focused on the transmission of factual information. This lack of non-verbal cues and forms of expression can negatively affect the relationship itself, as well as employees’ ability to express their issues and concerns, especially when they lack the “proper language” to explain them.

Negative Feelings Towards Each Other. The high potential for conflicts, the problem-centred communication and an overall sense of complexity of ITS that permeates participants’ responses can induce negative feelings towards ITS in general, despite all the displayed friendliness and helpfulness of ITS staff. Some of our participants explicitly described feelings of fear and worry in regards to ITS, as induced by Security training or of accidentally doing something wrong.

ITS practitioner reported negative feelings, too: they seem disappointed of employees not able to follow the rules or use the tools, they are afraid of employees open up holes in security or even of getting betrayed by insider threats. While the practitioners do not report about the feelings of single individuals the overall tone of the reports does transport these feelings.

Power Imbalance. Few participants explicitly described their relationship to ITS staff as hierarchical. Still, the overall appreciation of knowledge and expertise that runs through their answers also indicates a power imbalance in terms of knowledge and skills, which is amplified by employees’ dependency on ITS staff’s help and support. Some answers described ITS (staff) as obscure, working in the background, an “invisible force”. Others explicitly described the demeanour of ITS staff as arrogant, being talked down to and not respected for their fields of expertise, or being embarrassed. This power imbalance decreases trust and cooperation, and can cause disengagement between the employee groups.

Emotional Disengagement. One topic that ran through the answers was “distance” as well as an impersonal relationship. While this might be due to the nature of working interaction those employee groups have, others felt ITS staff to not be “people-persons”, that like to keep to themselves and “seem to dislike having to deal with colleagues”. On the employees’ side, we found some participants who actively avoided interaction with ITS themselves, rather trying to fix the issues themselves due to the negativity of their experiences with them. This disengagement is further fostered by practices of blaming the other. Blame users as “weakest link” on the practitioner side is a clear sign for disengagement. The practitioner are in their own circles they don’t care about how employees might feel about their measures, training and evaluations.

Blaming Others. Blaming of employees for security problems is a core theme that runs through practitioner statements and reports. Even reports that state that employees “need to be empowered” talk about employees making mistakes. The experience of being blamed is echoed in some of our survey participants’ statements. Some participants referred to ITS as acting “as if their colleagues are the problem, rather than external forces” (P6), others seem to have internalised this notion, referring to themselves as “trouble” (P72) and making them feel bad (P82). P66 framed it more positively, acknowledging their role and responsibility for security, and hoping to be perceived as “respectful IT users”. However, we also found participants blaming ITS staff as “useless", putting obstacles in their way, causing delays in their work, not prioritising their issues, being too strict and not willing to communicate in an understandable manner.

6 Therapy Framework

We found a significant number of indicators of dysfunctional relationships between the different CoPs. The most common signs are guilt and blaming, which run along and amplify all the aforementioned indicators of dysfunctional relationships. How can an organisation looking to build trust and collaboration between the different groups do transform those relationships? We suggest starting with Transactional Analysis (TA) and the OLaF questionnaire as measurement tools to assess how the organisation deals with error, blame and guilt, before looking at possible interventions inspired by therapy. Our complete Therapy Framework is shown in Fig. 2.

Learning from Errors: OLaF. We know from the HCI and Human Factors literature that good design can minimise the likelihood of human error on commonly executed tasks.Footnote 2 While this is true for employees as well as ITS, current ITS approaches tend to centre employee errors and put blame on them. To foster functional relationships between the CoPs, it is essential to stop the “scaring and bullying” [46] of any CoP and rather cultivate a culture of resilience and learning from errors. For this, we need to develop an understanding of how individuals as well as organisations deal with and learn from errors.

The behaviour of supervisors and colleagues, work processes, task structures as well as principles and values of an organisation with regard to the handling of errors influence the effectiveness of the successive learning stages [42] and therefore need to be incorporated. To assess the organisational climate for learning from mistakes, we propose OLaF (German: Organisationales Lernen aus Fehlern/organisational learning from mistakes) [41], a questionnaire designed to measure the organisational climate with regard to how mistakes are dealt with. Its strength is that it includes the perspectives of employees as well managers. The results help to generate ideas from different viewpoints on how human error can serve as avenue for individual and organisational learning processes. Complementary to OLaF, Knapp’s scale [31] can be used to assess the organisational climate in dealing with guilt to identify leverage points for joint optimisation.

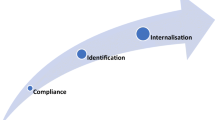

Evaluating Communication: Transactional Analysis (TA). As we have seen, fraught communication is one of the major hindrances to the functioning of the different relationships. Therefore it needs to be targeted specifically. Here, TA [11] known as “a communication theory which allows for the systematic analysis of a communication transaction between individuals” [36] can help. Individuals and organisational units have life positions or self-concepts – about themselves and others. In the position “I am o.k. - You are o.k.”, the individual or organisational unit accepts both themselves and others without judgement. The position “I am o.k. - You are not o.k.” is self-accepting and blaming others. The third position, “I am not o.k. - You are o.k.” is characterised by self-rejection and -belittling. Lastly, a negative attitude to oneself and others is reflected in the position “I am not o.k. - You are not o.k.” [36]. The ideal position is that both sides perceive each other as “o.k”. When people make errors, behaviour should be considered separately from the person - factors contributing to the error identified, and the interaction re-designed to stop triggering the error. Especially in the long-term cooperation with other people, these life positions are useful to understand the patterns and to derive appropriate interventions to get into the “o.k.” positions.

These insights provide a path to transform the dysfunctional relationships between the different CoPs. Current approaches to “improving” ITS in organisations start from the “I am o.k. - You are not o.k.”-mindset of ITS, as evidenced in the deficit construction of users, and futile attempts to “fix the human”. To some extent this view is also held by employees, who blame ITS as “baby-killers”, or less dramatically for creating obstacles to task completion, or not being not approachable. To foster collaboration and trust between these CoPs, both need to gain empathy for each other and their specific situations.

For this, everyone needs to stop looking for a culprit – someone to blame – and start cooperatively looking for solutions in joint optimisation [3], shifting from blame-centring to solution-centring. In socio-technical systems, it is essential that the requirements of different parties are met for optimal functioning of organisations [38]. Some core principles are outlined by Di Maio [18]: Responsible autonomy, adaptability, meaningfulness of tasks, and iterative development of processes based on feedback loops. We now propose practical interventions for mending the dysfunctional ITS relationships in organisations and enable joint optimisation based on approaches from individual and group therapy.

Applying Approaches from Individual and Group Therapy. To apply therapeutic approaches and principles of client-orientated individual psychotherapy in organisations, we first have to establish that the members of this group are in a psychological and dynamic relationship with each other [25]. Then, the determining conditions from individual and group therapy need to be created by a group-related leader. These conditions have been formulated by Hobbs [25] as follows: (1) Members of a group need to feel that they are given the opportunity to participate in matters that concern them directly, (2) All members of a group must be able to communicate freely with one another, (3) A non-threatening atmosphere needs to be created.

Developing Empathy, Trust and Cooperation. One major hindrance for functioning relationships between the different groups is lack of interpersonal contact and share language. To counter this, organisations should implement opportunities for employees to engage with each other as well as with security issues in a non-threatening manner. This has successfully been done e.g. in the form of security dialogues [4]; this is more likely to be successful after releasing tension and hostility through humour, and getting everyone to see the problem from everyone’s else side – Coles-Kemp et al. [34], for instance used clowns. Communication can be made more effective, and mutual understanding built, by recruiting security champions to act as a conduit – they can explain security to their fellow employees, help them master new behaviours, and report security that isn’t working back to the ITS CoP [9] that can serve as intermediaries between the different CoPs and facilitate communication and cooperation. Doing so helps decrease the experienced social distance, gives “a face to security” and further cultivates a sense of ITS as a shared activity and goal, fostering cooperation. Further, having an intermediary person to talk to will decrease the workload of ITS personnel and increase self-efficacy of CoPs in dealing with ITS issues. This will further decrease the negativity in communication as well as the imbalance of power between the CoPs. These attempts can be furthered by deploying Creative Security Engagements [35], an approach in which different stakeholders can address and reflect on their security needs in a participatory manner, bypassing the complexity of ITS terms by using creative methods.

Management Support. The relationships between management and ITS also needs attention, but diagnosis and suggestions of intervention are beyond the scope of this paper. However, beyond attending to their own relationships, management needs to lead, enable and resource the changes we have outlined for transforming the relationship between ITS and employees. They need to initiate the rebuilding process, and foster mutual empathy, trust and cooperation between the different CoPs within the organisation. Only then it is possible to cultivate flourishing cultures of security that build on mutual trust and cooperation, seizing human potential instead of demonising it, and framing ITS in a positive and productive manner. For this, it is of major importance that management and leadership actually take care of ITS, implementing information security strategies that are tailored to (1.) the specific CoPs and context, (2.) create a shared language between CoPs in terms of ITS, (3.) induce skill-building by communal and apprenticeship-learning and (4.) foster a sense of cooperation between CoPs in the pursuit of the shared goal of ITS of the organisation.

7 Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations. Our search for practitioner statements is not representative – we set out to find examples of those terms. We primarily chose vendors, conferences and magazines that have their origins in the US and UK. During our search we also found multiple statements that stress that security practitioners should not blame employees but rather the systems they are using – a leading example being the UK NCSC “People are the strongest link”Footnote 3 campaign, created by staff in its socio-technical team. But the fact remains that negative characterisation and language that blame employees is out there and dominates. Taken together with the studies of security in organisations [4, 8, 29], they provide evidence that dysfunctional relationship exist around ITS in a multitude of organisations. Furthermore, did we not link the practitioner statements with the survey results but left both parts for themselves. We might compare both sides more directly in future studies.

Concluding Remarks. The relationships between employees and ITS professionals can have a major impact on the well-being, work performance, job satisfaction and, in particular, on the handling of ITS in the everyday work of the persons concerned and are therefore of high relevance for organisations. Our study provides insights into the feelings of employees towards ITS professionals and shows that security relationships are often - despite various efforts - still dysfunctional.

We therefore introduced our Therapy Framework to analyse and identify dysfunctional relationships and gave suggestions how they could be mended. We argue that approaches from therapy can help improve relationships and can help bridging the distance between employees and ITS professionals. Organisations may profit from this framework by applying it to identify the problem and take action.

Notes

- 1.

We are not saying that employees don’t have to learn about security – there are new threats they need to be aware of, and security behaviours that are effective. But currently, security awareness wrongly seen as a “Cure-all” – it cannot “fix” security that is ineffective, security tasks that exceed human capabilities, or conflict with productivity targets organisations expect employees to meet.

- 2.

This is because not all situations that employees encounter can be foreseen at the design stage. For cost reasons, even not all foreseeable ones are designed and tested for usability – safety-critical systems, where the cost of the consequences of error can be extremely high, being an exception.

- 3.

https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/speech/people--the-strongest-link, accessed July 29th 2021.

- 4.

- 5.

https://newsroom.kpmg.com.au/weakest-link-going-wrong-cyber-security-australia/ accessed July 12th 2021.

- 6.

https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/GRQQYQBJ accessed July 12th 2021.

- 7.

https://www.knowbe4.com/products/kevin-mitnick-security-awareness-training/ accessed July 07th 2021.

- 8.

https://www.kaspersky.com/blog/the-human-factor-in-it-security/ accessed July 07th 2021.

- 9.

- 10.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fFFpj71G6sY accessed July 08th 2021.

References

Adams, A., Sasse, M.A.: Users are not the enemy. Commun. ACM 42(12), 40–46 (1999)

Albrechtsen, E., Hovden, J.: The information security digital divide between information security managers and users. Comput. Secur. 28(6), 476–490 (2009)

Appelbaum, S.H.: Socio-technical systems theory: an intervention strategy for organizational development. Manag. Decis. 35(6), 452–463 (1997)

Ashenden, D., Lawrence, D.: Security dialogues: building better relationships between security and business. IEEE Secur. Priv. 14, 82–87 (2016)

Ashenden, D., Sasse, A.: CISOs and organisational culture: their own worst enemy? Comput. Secur. 39, 396–405 (2013)

Bada, M., Sasse, A.M., Nurse, J.R.C.: Cyber Security Awareness Campaigns: why do they fail to change behaviour? In: Satapathy, S.C., Joshi, A., Modi, N., Pathak, N. (eds.) Proceedings of International Conference on ICT for Sustainable Development. AISC. Springer, Singapore (2016)

Barrett, S.: Overcoming transactional distance as a barrier to effective communication over the Internet. Int. Educ. J. 3, 34–42 (2002)

Beautement, A., Sasse, M.A., Wonham, M.: The compliance budget: managing security behaviour in organisations. In: Keromytis, A., Somayaji, A., Probst, C.W., Bishop, M. (eds.) Proceedings of the 2008 Workshop on New Security Paradigms, p. 47. Association for Computing Machinery, New York (2008)

Becker, I., Parkin, S., Sasse, M.A.: Finding security champions in blends of organisational culture. In: Acar, Y., Fahl, S. (eds.) Proceedings 2nd European Workshop on Usable Security. Internet Society, Reston (2017)

Beris, O., Beautement, A., Sasse, M.A.: Employee rule breakers, excuse makers and security champions: mapping the risk perceptions and emotions that drive security behaviors. In: Proceedings of the 2015 New Security Paradigms Workshop, NSPW 2015, pp. 73–84. Association for Computing Machinery, New York (2015)

Berne, E.: Spiele der Erwachsenen: Psychologie der menschlichen Beziehungen, rororo, vol. 61350: rororo-Sachbuch. Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl., Reinbek bei Hamburg, neuaufl. edn. (2002)

BetterCloud: State of Insider Threats in the Digital Workplace (2019)

Burdon, M., Coles-Kemp, L.: The significance of securing as a critical component of information security: an Australian narrative. Comput. Secur. 87, 101601 (2019)

Posey, C., Roberts, T.L., Lowry, P.B., Hightower, R.T.: Bridging the divide: a qualitative comparison of information security thought patterns between information security professionals and ordinary organizational insiders. Inf. Manag. 51(5), 551–567 (2014)

Clegg, S.: Frameworks of Power. Sage Publication, London (1989)

Coles-Kemp, L., Ashenden, D., O’Hara, K.: Why should i? Cybersecurity, the security of the state and the insecurity of the citizen. Politics Gov. 6(2), 41–48 (2018)

Coyle, D.: The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups, 11th edn. Bantam Books, New York (2018)

Di Maio, P.: Towards a metamodel to support the joint optimization of socio technical systems. Systems 2(3), 273–296 (2014)

Dogan, K., Vecchio, R.P.: Managing envy and jealousy in the workplace. Compens. Benefits Rev. 33(2), 57–64 (2001)

Galvin, K.M., Wilkinson, C.A.: The communication process: Impersonal and interpersonal (2006). Accessed 1 May 2011

Heath, C.P., Hall, P.A., Coles-Kemp, L.: Holding on to dissensus: participatory interactions in security design. Strateg. Des. Res. J. 11(2), 65–78 (2018)

Herley, C.: So Long, and no thanks for the externalities: the rational rejection of security advice by users. In: Proceedings of the 2009 Workshop on New Security Paradigms Workshop, NSPW 2009, pp. 133–144. Association for Computing Machinery, New York (2009)

Herley, C.: More is not the answer. IEEE Secur. Priv. 12(1), 14–19 (2014)

Herley, C., van Oorschot, P.C.: SoK: science, security and the elusive goal of security as a scientific pursuit. In: 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), pp. 99–120 (2017)

Hobbs, N.: Gruppen-bezogene Psychotherapie. In: Rogers, C.R. (ed.) Die klientenzentrierte Gesprächspsychotherapie. Client-Centered Therapy. FISCHER Taschenbuch (2021)

Inglesant, P., Sasse, M.A.: Information security as organizational power: a framework for re-thinking security policies. In: 2011 1st Workshop on Socio-Technical Aspects in Security and Trust (STAST), pp. 9–16 (2011)

Ponemon Institute: Managing Insider Risk Whitepaper (2016)

Budge, J., O’Malley, C., Blankenship, J., Flug, M., Nagel, B.: The Forrester Wave™: Security Awareness and Training Solutions, Q1 2020 (2020)

Kirlappos, I., Parkin, S., Sasse, M.A.: Learning from “Shadow Security”: why understanding non-compliant behaviors provides the basis for effective security. In: Smith, M., Wagner, D. (eds.) Proceedings 2014 Workshop on Usable Security. Internet Society, Reston, 23 February 2014

Klimburg-Witjes, N., Wentland, A.: Hacking humans? Social engineering and the construction of the “deficient user” in cybersecurity discourses. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 46(6), 1316–1339 (2021)

Knapp, L.: Zum Umgang mit Schuld in Organisationen. Entwicklung und erste Validierung einer Skala zur Erfassung eines Klimas der Schuldzuweisungen. Master thesis, Ruhr University Bochum, Chair for Organisational Psychology (2016)

Kocksch, L., Korn, M., Poller, A., Wagenknecht, S.: Caring for IT security: accountabilities, moralities, and oscillations in IT security practices. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2(CSCW), 1–20 (2018)

Labianca, G., Brass, D.J.: Exploring the social ledger: negative relationships and negative asymmetry in social networks in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 31(3), 596–614 (2006)

Coles-Kemp, L., Stang, F.: Making digital technology research human: learning from clowning as a social research intervention. Rivista Italiana di Studi sull’Umorismo (RISU) 2(1), 35–45 (2019)

Coles-Kemp, L., Hall, P.: TREsPASS Book 3: Creative Engagements. Royal Holloway (2016)

Lukenbill, W.B.: The OK reference department-using transactional analysis in evaluating organizational climates. RQ 15(4), 317–322 (1976). http://www.jstor.org/stable/41354348

Octavia, J.R., van den Hoven, E., de Mondt, H.: Overcoming the distance between friends. In: Electronic Workshops in Computing, BCS Learning & Development (2007)

Pasmore, W., Francis, C., Haldeman, J., Shani, A.: Sociotechnical systems: a North American reflection on empirical studies of the seventies. Hum. Relat. 35(12), 1179–1204 (1982)

Ponemon Institute: Global Encryption Trends Study (2019)

Proctor, T., Doukakis, I.: Change management: the role of internal communication and employee development. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 8(4), 268–277 (2003)

Putz, D., Schilling, J., Kluge, A., Stangenberg, C.: OlaF. Fragebogen zur Erfassung des organisationalen Klimas für Lernen aus Fehlern. In: Sarges, W. (ed.) Organisationspsychologische Instrumente: Handbuch wirtschaftspsychologischer Testverfahren; 2, pp. 251–258. Pabst, Lengerich [u.a.] (2010)

Putz, D., Schilling, J., Kluge, A., Stangenberg, C.: Measuring organizational learning from errors: development and validation of an integrated model and questionnaire. Manag. Learn. 44(5), 511–536 (2013)

Reason, J.: Human error: models and management. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 320(7237), 768–770 (2000)

Renaud, K., Searle, R., Dupui, M.: Shame in cyber security: effective behavior modification tool or counterproductive foil? In: Proceedings of the 2021 New Security Paradigms Workshop, NSPW 2021. Association for Computing Machinery, New York (2021, To appear)

Wilson, S.H.: Combating the Lazy User: An Examination of Various Password Policies and Guidelines (2002)

Sasse, A.: Scaring and bullying people into security won’t work. IEEE Secur. Priv. 13(3), 80–83 (2015)

Schneier, B.: Secrets and Lies: Digital Security in a Networked World. Wiley, New York (2000)

Susan, S., Shade, M.: People, the weak link in cyber-security: can ethnography bridge the gap? In: Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings, vol. 2015, no. 1, pp. 47–57 (2015)

Tjosvold, D., Yu, Z.Y., Hui, C.: Team learning from mistakes: the contribution of cooperative goals and problem-solving*. J. Manag. Stud. 41(7), 1223–1245 (2004)

Tracy, K., Eisenberg, E.: Giving criticism: a multiple goals case study. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 24(1–4), 37–70 (1990)

Whitten, A., Tygar, J.D.: Why Johnny can’t encrypt: a usability evaluation of PGP 5.0. In: Proceedings of the 8th Conference on USENIX Security Symposium, SSYM 1999, vol. 8, p. 14. USENIX Association (1999)

Zhu, Y., Nel, P., Bhat, R.: A cross cultural study of communication strategies for building business relationships. Int. J. Cross Cult. Manag. 6(3), 319–341 (2006)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Simon Parkin for his valuable feedback. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and fair review. The work was (partially) supported by the PhD School “SecHuman - Security for Humans in Cyberspace” by the federal state of NRW, Germany and also by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy - EXC 2092 CASA - 390781972.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

A Prolific Survey Questions

The following questions were asked in our prolific survey.

Your Experience with IT Security

-

1.

What are the first keywords that come into your mind when you think about the IT security personnel in your organisation?

-

2.

How helpful do you consider the IT security personnel?

-

3.

How would you describe the job of IT security personnel that you are in contact with?

-

4.

Have you had any negative experience with IT security personnel?

-

5.

Do you ever feel that you can’t follow organisational IT security rules? [All the time, Quite often, About half the time, Sometimes, Never]

-

6.

How would you describe your relationship to the IT security personnel in your organisation?

-

7.

How do you think the IT security personnel would describe this relationship?

-

8.

How much do you think the IT security personnel in your organisation knows about you and your everyday work requirements?

-

9.

What are negative attributes about your relationship with the IT security personnel in your organisation?

-

10.

What are positive attributes about your relationship with the IT security personnel in your organisation?

-

11.

How understandable do you find the communication from the IT security personnel?

-

12.

What indicators of how the IT security personnel feel about you have you noticed?

-

13.

How often do you have contact to IT security personnel? [Every day, Every week, Every month, One or few times a year, Lesser]

-

14.

Which of the following attributes best describe your relationship with the ITS personnel? [Productive, On eye-level, Functional, Respectful, Friendly, Empathetic, Cooperative, Supportive, Open minded, Collegial, Capable of Criticism, Unbiased, Trustful, Balanced, Dysfunctional, Arrogant, Incomprehensible, Top-down/Hierarchical, Uncooperative, Distant, Unsupportive, Patronising, Unapproachable, None of the above]

Demographic Questions

-

1.

How would you describe your current employment status? [Employed without management responsibility, Employed with management responsibility, Self-employed, A student, Other]

-

2.

Does your organisation have IT security personnel or even a IT-Security department?

-

3.

Do you currently work in an organisation that requires you to follow certain IT security rules (e.g. password policies, browsing restrictions, data protection policies) or use IT-Security tools (e.g. VPN, Password Managers, encrypted flash drives)?

-

4.

Do you have contact with the IT-Security personnel (e.g. in IT security trainings, when they send you security advice via mail, or when they help you after an security incident or data breach)?

-

5.

Do you work as a IT security specialist and/or was IT security part of your education?

-

6.

In which sector are you employed? [Private Sector, Public Sector, University or Research Institute, Other]

-

7.

In what type of field or department do you work (e.g. sales, human resources, IT, compliance, maintenance)?

B Security Vendor Statements with Sources

-

“Insider threats can originate from lack of awareness. For example, employees creating workarounds to technology challenges.” Footnote 4

-

“YOU are the weakest link: where are we going wrong with cyber security in Australia?”.Footnote 5

-

“Your employees might not trust you- many times, the relationship between the manager and the workers causes the threats to go undetected.” Footnote 6

-

“More than ever, your users are the weak link in your network security. They need to be trained by an expert like Kevin Mitnick, and after the training stay on their toes, keeping security top of mind.” Footnote 7

-

“The Human Factor in ITS: How Employees are Making Businesses Vulnerable from Within” Footnote 8

-

“What is the weakest link in today’s enterprise IT defenses? End users who violate security policy and are too easily fooled by social engineering attack.” Footnote 9

-

“[...] you know people are the weakest link in the security chain. You can have all the wonderful technologies and layers of Technology security protections in place but ultimately it comes down to the person, right?” Footnote 10

C Statement Clouds

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Menges, U., Hielscher, J., Buckmann, A., Kluge, A., Sasse, M.A., Verret, I. (2022). Why IT Security Needs Therapy. In: Katsikas, S., et al. Computer Security. ESORICS 2021 International Workshops. ESORICS 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 13106. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95484-0_20

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95484-0_20

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-95483-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-95484-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)