Abstract

Based on scientific insights, five key didactic principles for teaching reading comprehension are discussed in this chapter: (1) Reading in a meaningful and functional context, (2) in-depth interaction about texts, (3) explicit instruction in reading strategies, (4) integrating reading tasks with other subjects, and (5) monitoring factors associated with reading comprehension and differentiating instruction. These didactic principles are outlined with examples and practical advice. Several of these didactic principles have already been incorporated in well-known didactic approaches. This chapter also describes some graphic organizers, that can be used as a tool to actively process the content of the text and therefore enhance comprehension.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Keywords

1 Introduction

Well-developed reading comprehension skills are a prerequisite in order to participate in the literate world we live in. Teaching children how to comprehend written language, therefore, is one of the most significant educational goals. It is, however, also one of the most challenging skills to teach children. Reading comprehension is not only an enormously complex process in which various underlying skills play a role (see Chapter 1), it is also a process that mainly takes place in the mind of the reader without being directly visible. Learning how to comprehend a written text is a skill that children do not acquire on their own, it is a process that requires professional guidance and support, first and foremost provided by their teachers.

Over the past decades, many studies have examined the ways in which children can best be taught how to understand written texts (Hebert et al., 2016; Okkinga et al., 2018). The results of these studies have led to the description of numerous evidence-based insights which have a positive effect on students’ reading comprehension skills and their development. However, implementation of these insights by educational professionals such as teachers is not that simple. It is necessary to combine the conclusions of several studies on the same topic and subsequently derive the practical recommendations. The present chapter aims to help teachers apply scientific insights into their daily reading activities by providing evidence-based didactic principles, and translate them into teaching approaches, examples, and didactic tools. In Sect. 2.2 we discuss five effective didactic principles, followed by well-known teaching approaches and, in Sect. 2.3, we provide an example of a reading lesson which combines (most of) these principles. In Sect. 2.4, we describe the use of organizers, tools that can be helpful in actively processing the content of the text, applying different didactic principles.

2 Evidence-Based Didactic Principles

As noted before, various research has been undertaken to identify effective principles in teaching reading comprehension. In our research, we started with a report in which various studies and meta-analyses on effective principles from the Flemish educational board were described (Merchie et al., 2019). From there, we extended our research by examining other studies known in the field. Based on this research, we have identified and outlined below, five key principles:

(1) Reading in a meaningful and functional context, (2) In-depth interaction about texts, (3) Explicit instruction in a limited set of reading strategies, (4) Integrating reading education with other subjects, and (5) Monitoring factors associated with reading comprehension and differentiating instruction.

2.1 Reading in a Meaningful and Functional Context

Reading is first and foremost a meaningful and functional activity (Pearson et al., 2020; Swanson et al., 2014; Wigfield et al., 2016). Whether it is because the reader reads for pleasure or personal interest in order to learn, or because it is required for participation in our society, readers always start reading with a goal. Teaching reading and specifically reading comprehension, therefore, should not take place in an isolated context, but rather in a meaningful and functional context. By doing so, students experience that reading and having well-developed comprehension skills can be important, valuable, and useful to them (Swanson et al., 2014). School-related reading activities must resemble real-life reading tasks. This can be achieved by taking three factors into account while teaching reading comprehension skills: reading materials, reading purposes, and reading approach. These must be authentic and resemble the way people normally read by being meaningful and functional (Berardo, 2006).

2.1.1 Authentic Reading Materials

In selecting reading materials, it is important to keep in mind that in order to be meaningful and functional they must be student-centered, interactive, intriguing, and based on daily life. This can be accomplished by selecting authentic reading materials that match students’ interests or are related to the things they have learned before. But what are authentic reading materials? Bacon and Finnemann (1990) defined authentic materials as materials produced without any educational purpose and written by native speakers of the language of instruction. Lee (1995) suggested that these materials are considered more interesting by students because they were developed without an educational purpose and provide students with a more natural use of the language. In the case of reading comprehension, texts used for educational purposes often are written with a specific comprehension-related learning outcome in mind (e.g., practicing a specific strategy such as summarizing) and by doing so specific, natural traits of a language may vanish, or unnatural traits may be introduced. As a consequence, texts are perceived unnatural, without a true narrative, and not resembling texts that students encounter in their daily life.

Authentic reading materials can be found in all kinds of sources, such as non- fiction books, (graphic) novels, materials used in other school subjects such as biology, history, mathematics, and life sciences, instructions (e.g., manuals and recipes), biographies, letters or emails, newspaper articles, poems, and social media posts. To create a meaningful and functional context for students, it is important that students encounter various types of reading materials and learn how to read and comprehend them. Most teachers know about the importance of reading a lot, but variation in types of texts is also significantly related to students’ reading performance (Donahue et al., 2001). By reading different types of texts on the same subject, not only is a clear meaningful and functional context provided, but children also broaden their knowledge of the subject and learn to deal with different types of texts (see Sect. 2.2.4).

2.1.2 Authentic reading purposes

As with reading materials, reading purposes (or, in other words, the reason why students are required to read a text) should be authentic. This can be achieved by designing tasks that are also student-centered, interactive, intriguing, and based on daily life. Tasks should be centered around clear purposes such as solving a problem, starting a discussion, or finding out what happens to the main character of the story. Setting clear reading purposes that are meaningful and functional enhances students’ reading motivation and helps students to see why well- developed comprehension skills are important, valuable, and useful. However, in practice, reading purposes often do not resemble those set by students in real life such as acquiring information, but are centered around teaching a specific comprehension skill such as creating a model of the text or practicing a specific reading comprehension strategy (i.e., asking questions or summarizing, see Sect. 2.2.3). Take, for example, a biology text on the circulatory system (see Textbox 2.4). An authentic reading purpose or authentic reading goal would be to learn how blood travels through the body and to learn what the functions of the heart and lungs are. More specifically, an authentic reading purpose could be stated as: after reading the text, I know how blood travels through the body and what the function of the heart and lungs is. However, in practice, the purpose of reading such a text is often stated as: I can create a visual representation of the text. Although creating visual representations can be helpful in acquiring knowledge, in daily life, creating a visual representation is (almost) never the purpose of reading a text.

2.1.3 Authentic Reading Approach

The way in which a student reads a text should match the reason why they read it (reading purpose) and the type of text they read (reading material). In other words, the way that students read a text needs to be authentic. In Chapter 1, four main processes of reading comprehension were briefly described, namely: focusing on and retrieving information explicitly stated in the text, making straightforward inferences, interpreting and integrating ideas and information, and evaluating and critiquing content and textual elements. The approach used by the reader depends on his or her purpose, and the processes engaged depend on this purpose and the type of text. For example, when reading a recipe for making bread, it is important to explicitly retrieve information on how much flour, yeast, salt, and water you need and at what temperature you need to set the oven. Evaluating and critiquing the content or textual features of the recipe are less likely to be important. In instruction, it is important to match the reading approach to the approach most likely used in daily life. If the aim of the lesson is to practice a certain reading approach, this will have consequences for the choice of text.

2.2 In-Depth Interaction About Texts

Interacting on the content of the text (the meaning, the purpose, or the underlying relationships of the text) has a positive influence on students’ reading comprehension (Pearson et al., 2020; Shanahan et al., 2010). This concerns not only interaction among students and their teacher, but also interaction between students themselves. In-depth interactions can take place before, during, and after reading a text and can take place in pairs, small groups, or with the whole class. By discussing the content of the text, and specifically the information needed to reach the reading goal, students gain new insights that they themselves did not think about, leading to a better understanding of the text. Discussions can be about the underlying arguments and views of a text, about acquiring and remembering information by discussing ideas, facts, clues, and conclusions from the text, or about the students’ spontaneous and affective reactions while reading the text.

Interactions between the teacher and students that promote reading comprehension and reasoning about the text should be structured and content- oriented, and not be dominated by the teacher (Soter et al., 2008). This means the teacher’s role is to guide students, encourage interaction, and also make sure the discussion is about the text and does not remain superficial. Teachers can use various ways to promote interactions with students or among students themselves. First, teachers can discuss a text by asking open-ended extended reasoning questions instead of presenting children with multiple choice literal comprehension questions. Extended reasoning questions ask readers to “analyze, evaluate, and pull together information from the passage(s) and involve finding causes/effects, making inferences, analyzing, and using logical reasoning” (Peterson’s, 2008, p. 147). Examples of these extended reasoning questions are: why did the boy… ?, how do you think… ? and, what if the main character… ? Secondly, interactions can also be triggered by making comments which provoke a reaction, “I have never read anything so strange!”. Both these extended reasoning questions and textbased comments can be used to scaffold children in moving from a textbased understanding to a more situational understanding of the text.

Creating sufficient opportunities for interaction is not an easy job. In order for interactions to be successful in enhancing comprehension skills, it is important that all students have sufficient opportunity to interact. Allowing sufficient thinking time for all students to come up with an answer is crucial. Not all students are instantly able to respond to open-ended questions or feel comfortable doing so. A second way in which it is more likely that all students can contribute is by creating small groups of students and using cooperative reading activities where each group member must contribute to achieve the group goal (Johnson & Johnson, 2009; Slavin, 2010). In a small group of three or four, students have more opportunities to speak and are more likely to interact with each other. An example of a cooperative reading activity can be seen in Textbox 2.2.

2.3 Explicit Instruction in Reading Strategies

As mentioned in Chapter 1, a reading strategy can be seen as a “mental tool” readers can use to support, monitor, and restore their understanding of the text (Afflerbach & Cho, 2009). Readers with strong comprehension skills are identified as readers who (unconsciously) use combinations of various reading comprehension strategies while reading.

Although reading strategy interventions can have large positive effects on reading comprehension (for meta-analyses see Rosenshine & Meister, 1994; Sencibaugh, 2007; Swanson, 1999), these effects are mostly found in controlled settings with small groups of students and highly trained researchers as instructors. Effects of strategy interventions in classroom settings with regular teachers as instructors are smaller (for a meta-analysis see Okkinga et al., 2018). In addition, it is important that teaching reading strategies should never be seen as a goal in itself, but as a means to achieve better comprehension. Strategies should be used while reading the text and building a textbase and situation model, or after reading the text to improve the quality of the textbase and/or situation model. An adequate situation model, serving the reading purpose, should be the goal.

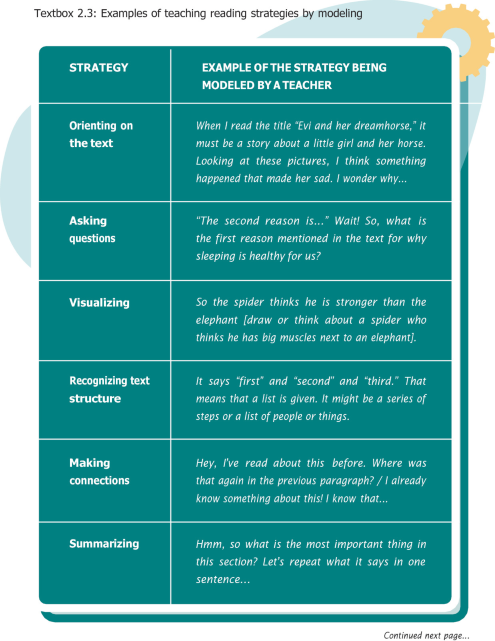

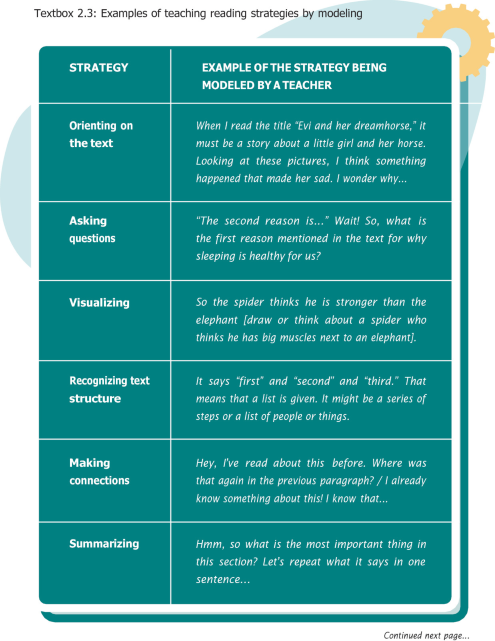

Despite these limitations, using reading comprehension strategies can be an effective way to enhance comprehension, especially when these comprehension strategies are taught in a meaningful way. As previously noted, reading comprehension mostly takes place in the mind of the reader without being explicitly visible. This poses challenges in teaching how to read a text in order to comprehend it, and in teaching how to effectively use reading comprehension strategies. One effective way to do so is modeling. Modeling refers to “the process of offering behavior for imitation” (Tharp & Gallimore, 1988, p. 47). A common way to do so is by using thinking aloud procedures. Thinking aloud involves the process of making thoughts audible by saying what one is thinking while performing an action. In modeling reading comprehension strategies, an expert reader (mostly the teacher, but can also be done by a student) reads aloud part of the text and before, during and after reading indicates what they are thinking. By doing so, the expert not only shows students how to apply a strategy themselves, but also when to apply which strategies. Examples of how to model different strategies are presented in Textbox 2.3.

Although the National Reading Panel (2000) has distinguished more than 15 comprehension strategies, there is evidence for only a limited set of these strategies to have a positive effect on reading comprehension, especially when taught and used in combination (Okkinga et al., 2018; Pressley, 2006; Shanahan et al., 2010). Seven effective strategies are briefly described below.

-

1.

Orienting on the text: making predictions and setting reading goals

When orienting on a text, the reader views the text globally by looking at the text characteristics, like pictures, headings, layout, and paragraphs. By linking the information that they superficially extract from the text to their prior knowledge, the reader can make predictions about the type of text and its context. This allows them to set a reading goal and be prepared for reading the text. It is important that students do not make haphazard predictions and therefore possibly get a wrong idea of the text. In those circumstances, they would have to adjust their goals and expectations while reading. At elementary school level, predicting is best done with the guidance of the teacher.

-

2.

Asking questions

Asking students questions about a text is a good way to promote students’ reading comprehension. Thinking about text-oriented questions, for example, questions about the sequence in the text, comparisons, opposites, similarities and differences, and causes and effects, contributes to reading comprehension. Even more effective is when students learn how to ask themselves these questions. When students ask their own questions out of curiosity, they are actively clarifying the text for themselves, becoming more aware of their own reading process, and staying motivated to read. Based on the prior knowledge and the predictions students make, questions will come up while reading: “What does this paragraph say?” “I don’t understand. How has this happened?” “I wonder why… ?” etc.

-

3.

Visualizing the content of the text

To get a better grip on the content of the text, it helps to visualize or represent the text. This also contributes to generating further thoughts about the text. While reading, images may come to mind automatically and can be visualized by drawing or sketching. Also, stories can be acted out by a group of students, so that they can empathize with the characters. Relationships that are described in a text, for example causes and consequences or means and goals, can also be visualized by making schemes or mind maps (Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1 is an example and section 2.4 provides more information on graphic organizers).

-

4.

Recognizing text structure

Recognizing text structure helps students to interpret and understand the text in an effective and efficient way. When relationships between parts of a text are clarified using connectives (e.g., “because” or “therefore”) to clarify a reason-consequence structure, readers do not have to infer the meaning of relationships themselves. Interpreting the text will cost less cognitive energy, reading times will be shorter, and readers will develop a better text comprehension (Degand & Sanders, 2002; Sanders & Noordman, 2000). This requires instruction about global text structure, the structure of a paragraph or sentence, and the use of connectives, for example, the structural features of a narrative text (characters, setting, goal, problem, plot, solution, and theme) or recognizing the words that indicate a certain relation (e.g., a sequence, comparison, contrast, cause-effect, or an enumeration). Text structure can be mapped in graphic organizers (see section 2.4).

-

5.

Making connections

To understand a text, a reader often has to “read between the lines.” In other words, infer new information that is not literally written in the text. To do so, the reader has to relate essential information that they have read before to the new information in the text and combine this with their prior knowledge. This is not easy to teach, since a reader does this mostly automatically. Thinking out loud by the teacher helps students to learn how to make these connections themselves (modeling).

-

6.

Summarizing

By summarizing a text, in any way whatsoever, the reader must think about the essence of a text and discard irrelevant matters. By summarizing a text together in interaction, students can discuss what they think is most important. The feedback of a teacher or other students while summarizing may lead to a better understanding of the text. By summarizing, students remember the essence of a text better, which is useful when reading about a subject you have to study, for example, the Middle Ages. A summary can be a written piece of text or a diagram with drawings (see section 2.4). Summarizing can also be done by retelling a story or recalling an expository piece aloud.

-

7.

Monitoring and clarifying comprehension

While reading, comprehension problems may arise, for example, when the reader does not know the meaning of a word or does not understand a sentence or part of the text. When the reader monitors their own comprehension of the text, certain recovery strategies can be used to clarify things. At word level, students can use word learning strategies. These are strategies to find out the meaning of the word yourself. Sometimes the meaning of a word can be deduced from its context. Therefore, it is useful to read the sentence or part of the text again. Another strategy is to segment the word into parts. Prefixes, suffixes, and base words can sometimes give clues about the meaning, for example, the word “unreliability” (un-rely-able-ity). Also, students should understand it is not always necessary to know all the words to comprehend a text. When comprehension problems occur at the sentence level, it can be effective to reread the sentences around it. Again, teaching to monitor your own reading comprehension is best done by modeling.

2.4 Integrating Reading Education with Other Subjects

Background knowledge is a crucial part of reading comprehension (see Chapter 1), so knowledge building is essential. The more knowledge students have about the world around them, the more they can rely on that while reading texts with new information. One way to build knowledge is to read all kinds of informative texts in other school subjects, such as geography, history, or (life) science. By reading texts from other school subjects, students not only acquire new knowledge, they also learn new subject-specific words. In addition, students learn to apply the reading skills they have learned before in new informative texts. Also, the integration of reading with other subjects often ensures that students become more engaged and motivated readers. In Textbox 2.4 the integration of reading education with other subjects is illustrated by an example lesson.

Reading can also very naturally be integrated with writing. Instruction in reading comprehension can have a positive effect on the quality of students’ writing. Instruction in writing also leads to better reading comprehension. Students draw on similar knowledge representations and cognitive processes when they read and write (Graham & Hebert, 2010; Graham et al., 2018). Activities that integrate the two language skills can be: writing about the continuation of the story by using your imagination, writing summaries, writing notes, and answering or generating questions about a text in writing.

2.5 Monitoring Factors Associated with Reading Comprehension and Differentiating Instruction

How well a student is understanding texts can be monitored in various ways. The most obvious way is to take a written reading comprehension test. These summative tests often consist of texts and questions, or texts followed by an assignment. The goal of a summative test is to assess what the student has achieved at the end of an educational program or period of study (such as school terms). Depending on the results, teachers can make decisions about the future reading lessons and the amount of attention needed for certain types of text or reading processes. Students may struggle with one or more factors of reading comprehension that they need to work on, such as decoding, vocabulary, and background knowledge, which will impact their results. In addition, students’ use of strategies, motivation to read, and the degree to which they feel they have control over their own learning process should be considered, as these aspects also affect the reading results. To monitor this, a teacher can talk about students’ reading process with them or observe how the students construct comprehension when they read and think out loud. Another way to gain insight into the reading process is to ask the student to explain their answers while answering questions about a text (Cain & Oakhill, 2006). With these more formative ways of testing, teachers gain more insight into the student’s reading processes (Brookhart et al., 2010; Witmer et al., 2014). The purpose of formative assessment is not to determine the level of understanding, but to improve the future learning process by giving feedback. By using both types of tests (summative and formative), teachers can decide which students need extra attention and which aspects of reading need further work.

Monitoring students reveals student differences in their level of reading comprehension and in their educational needs. It is therefore necessary to differentiate between students. Differentiation can be sought in the choice of texts. A text should not be too difficult as students will become unmotivated and reading goals may not be achieved. On the other hand, students do not learn from texts that are too easy. The trick is to challenge the student at exactly the right level. Teachers can determine the difficulty of a text by looking at the proportion of unknown words, or its coherence and structure. As mentioned before, the use of connectives such as “although,” “because,” or “on the contrary” in a text has a positive effect on its readability. Students with little background knowledge, for example, benefit from highly coherent texts with a clear structure (Kamalski, 2007). Readers with a lot of prior knowledge do not need the text signals that make the relations explicit. Simplifying texts so that they match the level of the student is usually not a good idea; this often leads to poor, meaningless texts. Instead of adapting the texts for readers lacking comprehension skills, differentiation can also be achieved by giving explicit instruction in word meaning, the use of reading strategies, and text structure. This extra instruction can give students the extra help they need to understand the same texts as their classmates.

3 Teaching Approaches Combining Didactic Principles

To ensure that reading comprehension is taught as effectively as possible, it is important to integrate the didactic principles as much as possible, for example, by reading an authentic text together, modeling how to enhance comprehension using one or two strategies, giving students a cooperative assignment about the text, and finally discussing their outcomes together. The principles reinforce each other. Some of the didactic principles have already been incorporated in a number of well-known teaching approaches. In the following sections, we describe three effective approaches in which (most of) these principles recur.

3.1 Reciprocal Teaching

Reciprocal teaching is an approach where students gradually assume the role of teacher during reading sessions with a small group of students. In these sessions, students apply four reading strategies: predicting, asking questions, clarifying ambiguities, and summarizing. Before reciprocal teaching can be used successfully, teachers need to model the four strategies separately and students need time to practice them. Once students have learned the strategies, they take turns in leading a conversation about the meaning of a text. Several studies show a positive effect of reciprocal teaching on reading comprehension (Rosenshine & Meister, 1994; Spörer et al., 2009). It encourages students to be actively involved in the reading process and enables them to monitor their comprehension as they read.

3.2 Collaborative Strategic Reading (CSR)

A similar approach is Collaborative Strategic Reading (CSR): reciprocal teaching combined with collaborative learning. Researchers have found positive results for CSR on reading comprehension (Karabuga & Kaya, 2013; Klingner & Vaughn, 2000). With CSR, students learn to apply cognitive and metacognitive strategies, like previewing (orienting on) the text, monitoring and clarifying comprehension, and summarizing. Initially, teachers spend time teaching students to use these strategies. Once learned, students work together in small, heterogeneous groups where each group member is assigned a specific role, such as a reporter who summarizes the main ideas, or a leader who determines the best strategy to use. The teacher acts as a coach in CSR.

3.3 Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction (CORI)

Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction involves working on a scientific theme for a number of weeks. Students formulate learning questions around this theme and choose texts that can help them in answering these questions. After a few weeks they present the results of the learning questions to each other. Other learning areas such as history are integrated as much as possible. Again, the teacher acts as a coach and provides reading strategies and interesting books and texts at different levels to support students. Research shows positive effects of CORI on reading comprehension and reading motivation (Guthrie et al., 2007). By embedding reading comprehension in a science/physics theme, the reading tasks become functional, and transfer can take place. A disadvantage of CORI is that it often only concerns informative texts.

4 Using Organizers in Reading Lessons

After reading a text, meaningful reading assignments should take place in which students actively process the content of the text. Deeper processing of text content may identify weaknesses in the text models that students have created. The reader finds out which part or parts of the text are not understood completely and, by using reading strategies, tries to enhance comprehension of that specific part. Also, students remember the content of a text better when working on assignments that activate their understanding of the text. A tool to enable students to actively process the content of texts is the use of organizers, such as mind maps. With an organizer, the content of (parts of) the text is displayed in a graphical, structured way. Organizers clarify how pieces of information in the text are related to one another, or how new information is related to knowledge students already had. Using schematic representation of the text is a study technique that increases the effectiveness of learning (Robinson et al., 1995; Hall et al., 1992). With the use of organizers, the teacher can integrate several didactic principles into the reading lessons. For example, organizers can be helpful in using reading strategies such as visualizing and summarizing. Also, creating an organizer in pairs or small groups automatically initiates interaction and discussion between students about the content of a text. Moreover, teachers can monitor students’ comprehension of a text while observing students discussing aloud and completing an organizer.

Depending on the type of text and reading goal, various organizers can be used to structure texts. In the following sections, we discuss a number of organizers: mind maps, tables, Venn diagrams, schemes, and story maps.

4.1 Mind Maps

Mind maps are often used to activate background knowledge before reading an informative text. Students think about what they know about the subject written in the center of the mind map. Thoughts are divided into categories and related to each other. After reading the text, this mind map can be supplemented with new information from the text. It is important to structure the information in the mind map, so that the relationships between words become clear (Fig. 2.1).

4.2 Tables

For informative texts that involve comparing different things from the same category, a table can be made. In such a table, similarities and differences are mapped in a structured way. For example, in a text with information about different animals, a table like in Fig. 2.2 can be filled out.

4.3 Venn Diagrams

When only two concepts, phenomena, persons, animals, or things are compared in a text, a Venn diagram can be helpful to clarify the differences and similarities. The differences are written in the outer part of the circles, and the similarities in the overlapping part of the circles (Fig. 2.3).

An example of a Venn diagram (Note This is an adapted version of the figure presented in https://nl.pinterest.com/pin/map-skills-location-social-studies-unit--431853051760868451/)

4.4 Schemes

Texts in which causes and consequences are discussed, can be represented in a scheme. Causes and consequences can be written in different boxes and connected by arrows. This type of organizer can also be used for texts where problems and solutions are described (Fig. 2.4).

4.5 Story Maps

A final example of an organizer is the story map. This is most suitable for narrative texts. By filling out a story map, students need to think about story elements like the characters, plot, setting, problem, and resolution of a story. There are basic story maps that focus on the beginning, middle, and end of the story. More advanced organizers also include elements like character traits or detailed information. With a story map, students can make a complete overview of a narrative text (Fig. 2.5).

References

Afflerbach, P., & Cho, B. (2009). Identifying and describing constructively responsive comprehension strategies in new and traditional forms of reading. In S. E. Israel & G. G. Duffy (Eds.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (pp. 69–91). Routledge.

Bacon, S. M., & Finneman, M. D. (1990). A study of the attitudes, motives and strategies of university foreign-language students and their disposition to authentic oral and written input. Modern Language Journal, 74, 459–473.

Berardo, S. A. (2006). The use of authentic materials in the teaching of reading. The reading matrix, 6(2). https://readingmatrix.com/articles/berardo/article.pdf

Brookhart, S. M., Moss, C. M., & Long, B. A. (2010). Teacher inquiry into formative assessment practices in remedial reading classrooms. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17, 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940903565545

Cain, K., & Oakhill, J. (2006). Assessment matters: Issues in the measurement of reading comprehension. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 697–708.

Degand, L., & Sanders, T. (2002). The impact of relational markers on expository text comprehension in L1 and L2. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 15(7), 739–757.

Donahue, P. L., Finnegan, R. J., Lutkus, A. D., Allen, N. L., & Campbell, J. R. (2001). The nation’s report card: Fourth-grade reading 2000 (NCES 2001–499). National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2010). Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Graham, S., Liu, X., Bartlett, B., Ng, C., Harris, K. R., Aitken, A., Barkel, A., Kavanaugh, K., & Talukdar, J. (2018). Reading for writing: A meta-analysis of the impact of reading interventions on writing. Review of Educational Research, 88(2), 243–284.

Guthrie, J. T., McRae, A., & Klauda, S. L. (2007). Contributions of concept-oriented reading instruction to knowledge about interventions for motivations in reading. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 237–250.

Hall, R. H., Dansereau, D. F., & Skaggs, L. P. (1992). Knowledge maps and the presentation of related information domains. The Journal of Experimental Education, 61, 5–18.

Hebert, M., Bohaty, J. J., Nelson, J. R., & Brown, J. (2016). The effects of text structure instruction on expository reading comprehension: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(5), 609–629.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational Researcher, 38(5), 365–379.

Kamalski, J. (2007). Coherence marking, comprehension and persuasion. On the processing and representation of discourse. Dissertation. Utrecht University.

Karabuga, F., & Kaya, E. S. (2013). Collaborative strategic reading practice with adult EFL learners: A collaborative and reflective approach to reading. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 106, 621–630.

Klingner, J. K., & Vaughn, S. (2000). The helping behaviors of fifth graders while using collaborative strategic reading during ESL content classes. Tesol Quarterly, 34(1), 69–98.

Lee, W. Y. (1995). Authenticity revisited: Text authenticity and learner authenticity. ELT Journal, 49(4), 323–328.

Merchie, E., Gobyn, S., De Bruyne, E., De Smedt, F., Schiepers, M., Vanbuel, M., Ghesquière, P., Van den Branden, K., & Van Keer, H. (2019). Effectieve, eigentijdse begrijpend leesdidactiek in het basisonderwijs. [Effective, contemporary reading comprehension didactics in primary education]. VLOR Vlaamse Onderwijsraad.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Okkinga, M., Van Steensel, R., Van Gelderen, A., Van Schooten, E., Sleegers, P. J. C., & Arends, L. R. (2018). Effectiveness of reading-strategy interventions in whole classrooms: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychological Review, 30(4), 1215–1239.

Pearson, P., Palincsar, A., Biancarosa, G., & Berman, A. (2020). Reaping the rewards of the Reading for Understanding Initiative. National Academy of Education.

Peterson’s. (2008). Master critical thinking for the SAT. Peterson’s Nelnet Co.

Pressley, M. (2006). Reading instruction that works: The case for balanced teaching. Guilford Press.

Robinson, D. H., & Kiewra, K. A. (1995). Visual argument: Graphic organizers are superior to outlines in improving learning from text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(3), 455–467. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.87.3.455

Rosenshine, B., & Meister, C. (1994). Reciprocal teaching: A review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 64(4), 479–530.

Sanders, T., & Noordman, L. (2000). The role of coherence relations and their linguistic markers in text processing. Discourse Processes, 29, 37–60.

Sencibaugh, J. M. (2007). Meta-analysis of reading comprehension interventions for students with learning disabilities: Strategies and implications. Reading Improvement, 44(10), 6–22.

Shanahan, T., Callison, K., Carriere, C., Duke, N. K., Pearson, P. D., Schatschneider, C., & Torgesen, J. (2010). Improving reading comprehension in kindergarten through 3rd grade: A practice guide (NCEE 2010–4038). National Center for Educational Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Slavin, R. E. (2010). Co-operative learning: What makes group-work work? In H. Dumont, D. Istance, & F. Benavides (Eds.), The nature of learning: Using research to inspire practice (pp. 161–177). OECD Publishing.

Soter, A. O., Wilkinson, I. A., Murphy, P. K., Rudge, L., Reninger, K., & Edwards, M. (2008). What the discourse tells us: Talk and indicators of high-level comprehension. International Journal of Educational Research, 47(6), 372–391.

Spörer, N., Brunstein, J. C., & Kieschke, U. L. F. (2009). Improving students’ reading comprehension skills: Effects of strategy instruction and reciprocal teaching. Learning and Instruction, 19(3), 272–286.

Swanson, E., Hairrell, A., Kent, S., Ciullo, S., Wanzek, J. A., & Vaughn, S. (2014). A synthesis and meta-analysis of reading interventions using social studies content for students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 47, 178–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219412451131

Swanson, H. L. (1999). Reading research for students with LD: A meta-analysis of intervention outcomes. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32(6), 504–532.

Tharp, R. G., & Gallimore, R. (1988). Rousing minds to life: Teaching, learning, and schooling in social context. Cambridge University Press.

Wigfield, A., Gladstone, J. R., & Turci, L. (2016). Beyond cognition: Reading motivation and reading comprehension. Child Development Perspectives, 10(3), 190–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12184

Witmer, S. E., Duke, N. K., Billman, A. K., & Betts, J. (2014). Using assessment to improve early elementary students’ knowledge and skills for comprehending informational text. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 30(3), 223–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2014.924454

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bruggink, M., Swart, N., van der Lee, A., Segers, E. (2022). Evidence-Based Didactic Principles and Practical Teaching Suggestions. In: Putting PIRLS to Use in Classrooms Across the Globe. IEA Research for Educators, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95266-2_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95266-2_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-95265-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-95266-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)