Abstract

Drawing on framing, at both methodological and theoretical levels, this chapter examines the framing of the COVID-19 pandemic in two mainstream Zimbabwean weekly newspapers. The chapter answers two questions: In what ways did the mainstream media in Zimbabwe frame the COVID-19 pandemic? To what extent did the coverage sync with the public sphere model of biocommunicability? We note that the private mainstream press largely adopted a thematic framing approach of the ruling regime’s COVID-19 plan, by highlighting corruption, mismanagement, and overt politicisation of the pandemic. The state-controlled public press broadly adopted a episodic framing approach that focused on the state’s COVID-19 intervention over time, mostly presenting these interventions as a success story. We argue that the episodic framing approach of the private press attempted to hold the state to account. The thematic framing approach of the state-controlled public press backgrounded the regime’s failure to stem the pandemic tide and presented the intervention in ‘sunshine journalism’. Both framing approaches violated established health reporting practices, as outlined in the biocommunicability model. We conclude that ‘the hear, speak and see no evil news framing approach’ of the public media and the anti-regime frames prevalent in the private press reflect prevalent media polarisation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Framing analysis

- Zimbabwe mainstream media

- COVID-19. Biocommunicability model

- The Sunday Mail

- Daily News on Sunday

Introduction

The purpose of this chapter is to examine how two mainstream newspapers, the state-controlled weekly newspaper The Sunday Mail and the privately owned Daily News on Sunday, framed the COVID-19 health crisis in the Zimbabwean context. By mainstream we mean media with a national reach (newspapers, radio, television) whether state controlled or privately controlled. The available literature on media and COVID-19 examined (Online—Twitter) citizens’ responses to the government’s COVID-19 response especially in the aftermath of the Defence Minister’s utterances (Shumba et al. 2020). There was no research situated at the intersection of the pandemic and mainstream media discourses by the time of this research. This chapter sought to fill this lacuna through a comparative examination of how the two selected weekly newspapers framed the pandemic.

Post-2000 Zimbabwe has been characterised by numerous health pandemics. For example, before the outbreak of COVID-19 in the country in April 2020, the country had suffered a cholera and typhoid outbreak. The country was characterised by a collapsed health delivery system, poor sanitation, and lack of clean water in urban areas (Chigudu 2019). ZANU-PF’s many years of national economic mismanagement, neglect, and corruption collapsed the health delivery system contributing to these pandemics. In early 2020, as the COVID-19 virus ravaged the USA, Zimbabwe’s Defence Minister and the ruling party’s national chair, Oppah Muchinguri, infamously remarked that the virus was God’s punishment to the West for imposing economic sanctions on the country. This statement had the potential to undermine the country’s response to, and citizens’ perceptions of, the pandemic as it could have led to a ‘false sense of immunity’. This, together with the citizenry’s suspicions of corruption and lack of political will by the elite to improve the country’s health delivery system (see Chigudu 2019), makes it worthwhile to interrogate how the mainstream Zimbabwean media framed the COVID-19 pandemic.

This chapter is organised as follows: The next section reviews existing literature on the media coverage of pandemics. It is followed by the theoretical and conceptual framework—framing theory (Entman 1993) and the public sphere concept of biocommunicability (Briggs and Daniel 2020), both of which are germane to this chapter. The theoretical framework is followed by a discussion of framing analysis which is the methodology adopted in this chapter. The findings section, the discussion, and the chapter’s conclusion follow thereafter.

Literature on Media Framing of COVID-19

While the pandemic monopolised media attention, intellectual research on it was still work in progress. Mutua and Oloo Ong’ong’a (2020) argued that the COVID-19 pandemic was framed in the media, along crime-related frames. These included protest frames and the hoarding of essential goods during the pandemic. Mutua and Oloo Ong’ong’a (2020) identified xenophobic frames especially in international media. Xenophobic frames blamed China for being responsible for the outbreak of COVID-19. These frames, they argue, led to the stigmatisation and stereotyping of Chinese people especially in countries where they are a minority. Jo and Chang (2020) argue that international media framing of the pandemic had a positive political influence on how Koreans viewed their government. They found that Korean media utilised an expanded framing which compared the quarantine and performance of Korea and other countries. But in the Korean case, media frames of the pandemic ‘induced a positive change in people’s attitudes towards the government [which led to] a major victory for the ruling party in legislative elections’ (Jo and Chang 2020, p. 1). Thomas et al. (2020) noted that media frames of the COVID-19 were, ‘largely based on societal issues with the theme of economic disruption prevalent’ (p. 11). Like Mutua and Oloo Ong’ong’a (2020) they also identified frames of blame that were commonly implied based on the origins of the virus. But unlike Mutua and Oloo Ong’ong’a (2020), Thomas et al. (2020) found frames that apportioned blame less frequently in the Australian media, that is, ‘The Australian print media were slow to report on COVID-19 pandemic and were reluctant to apportion blame’ (p. 1).

Two important takeaways emerge from this literature. First, the literature relied on different methods of data gathering and analysis. Most of them, however, relied on traditional content analysis methods of news corpus. Some of these studies relied on computer software-assisted analysis. For example, the study by Jo and Chang (2020) relied on Topical Model methods, while the study by Thomas et al utilised NVIVO software. Second, at the time, there was no known research on media framing of this COVID-19 pandemic emanating from the African context. Zimbabwe’s mainstream media had been viewed as polarised and discordant. High levels of polarisation in the coverage of COVID-19 usually contributed to the politicisation of public attitudes towards COVID-19 (Hart et al. 2020). We hence seek to understand how the mainstream media framed the COVID-19 pandemic. This chapter makes a contribution to literature on mainstream media coverage of the pandemic in a polarised media context in Africa.

Theoretical Framework

There are two concepts germane to this chapter. One is the framing theory (Entman 1993). The second one is the public sphere concept of biocommunicability (Briggs and Daniel 2020). Framing theory was utilised as theoretical and analytical lenses through which to understand communication texts (Burgers et al. 2016). Framing theory asserts that how a news issue is presented in the media makes a difference (Vreese 2017). Some scholars, such as Gamson (1992), see framing theory as an extension of agenda setting.

At the core of framing theory is the proposition that every news story carries with it verbal and/or visual information that directly or implicitly suggests what the problem is, how it can be addressed (Iyengar and Simon 1993), and who is responsible for it (Munoriyarwa 2020). These frames originate with journalists and their beliefs about how reality is constructed (D’Angelo and Kuypers 2010). Framing theory assumes that the media decide on what topics will be presented and how they will be presented (Entman 1993). How an issue is presented in a news medium can alter public perceptions of the issue. Framing assumes that audiences may interpret news in ways that agree with or contradict the preferred frames supplied by the journalists (Gamson 1992). It also states that frames are reinforced positively or negatively every time they are evoked (Burgers et al. 2016), and frame building is a systematic process that takes place over time (Entman 1993). Framing theory further assumes that many factors collide to influence journalists’ selection of both the news item and the preferred frame. Among these factors are news values, news sourcing, editorial policies (Entman 1993), and individual journalists’ biases, beliefs, values, and norms. Framing is thus arguably a subjective process. Framing theory helps us understand how these framing attributes like news values, news sources, editorial policies, were utilised by two mainstream media outlets to frame the COVID-19 pandemic in the country.

The public sphere concept of biocommunicability, which is utilised together with framing theory, imagines the audience as ‘composed of citizens rather than patients and consumers’ (Briggs and Daniel 2020). Health information helps citizens and policymakers make collective decisions about the public interest (Hall and Meike 2019). The concept accepts health as ‘contested, contingent and [a] firmly political concept’ (Holland 2017, p. 2). This means, it is ‘public flow of information that enable citizens to weigh in on public policies and government compliance with them’ (Holland 2017, p. 2). Holland (2017) equates the public sphere concept of biocommunicability to civic-oriented health journalism, ‘wherein, audiences are addressed as having a stake in health issues and journalists assume the role of assisting them in grasping the scope, relevance and potential impact of issues’ (Holland 2017, p. 3).

At the centre of the public sphere concept of biocommunicability is the facilitative and the interpretive (Hall and Meike 2019) role of health journalism. These two roles envisage health news reporting as open to public debate, as opposed to linear conceptualisations of health communication that see (health) experts as communicating with an ignorant public (Briggs and Daniel 2020). The concept, furthermore, emphasises analysing and interpreting complex, ‘health issues and discussing solutions’ (Holland 2017, p. 11). We seek to establish how this was executed, if at all it was, in the selected newspapers. Under the public sphere concept conflicting views about a health issue will be selected, and ‘controversy is framed as conflict between different stakeholders or (harmed) citizens’ (Briggs and Daniel 2020, pp. 39–40). We were also interested in the conflicting and/or uniform framing of the COVID-19 pandemic by the selected newspapers. Thus, we examined areas of consensus and dissensus in the selected newspapers’ framing of the pandemic.

Data and Method

Premised on a constructivist perspective, this chapter is based on three months of data gathered from two weekly newspapers—The Sunday Mail and The Daily News on Sunday. These are Zimbabwe’s most popular weeklies with huge circulation and readership figures (ABC 2018). The Sunday Mail is publicly owned but government controlled, and the Daily News of Sunday is privately owned. However, there was speculation that the country’s spy agency acquired a stake in Associated Newspapers of Zimbabwe (ANZ), the publishers of the Daily News on Sunday. We examined the four possible elements of news frames (Entman 1993), in every story that we analysed. These are problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and recommendation. To identify these four elements of a news frame, we looked at how news stories constructed them using devices like news sourcing. How journalists source their news is important to the process of news framing (Burgers et al. 2016). Sourcing determines the frame that emerges, through preference (or the lack thereof) of voices in the story and the importance accorded to them through placement (Gamson 1992).

We also looked at words-lexical choices. Lexical and syntactical configurations do sway readers in shaping and understanding their messages (Gamson 1992). Other elements we look at include positioning of the news story in question. For instance, when a story is headlined, it assumes a framing importance (Iyengar and Simon 1993). In addition to this, headlines are also important as they reveal the ‘framing slant’ of the news story. Because the headline is the first news rhetoric device to be seen by the reader, it therefore serves the purpose of setting the agenda. Thus, we look at these aspects as elements that create salience (foregrounding) of news items and, simultaneously, backgrounding of others. This is important because beyond identifying the frames utilised in the analysed stories and themes emerging from the data, we seek to establish the agenda that the newspapers intended to set and the actions they wanted to take. It is not possible for a single chapter to analyse all framing devices in the analysis (Borah 2011). For this chapter, we draw on those elements discussed here.

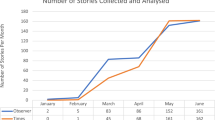

This chapter relied on both hard news stories and opinionated journalism stories that appeared in both newspapers. By ‘opinionated journalism’ we adopt Steele and Barnhurst’s (1996) definition of the term to mean any news pieces where journalists expressed their opinions and judgements of events and issues. This included, among other practices, editorials, news commentaries, opinion pieces, feature stories and many more. To avoid ‘drowning’ in data, we sampled two stories from each of the two weeklies for every week. This gave us a total of eight (8) stories from each of our newspapers per month and, thus, 16 stories from both in a month. We hence had 48 stories to read, as part of the corpus, in the three months sampled. These were the stories we subjected to framing analysis. We noted that some of the stories repeated the same issues, and we, hence, dropped them. This left us with a manageable sample of 33 stories. Framing analysis has been criticised for lacking specificities (Hallahan 2008) and, therefore, difficult to preclude causal relationships. Critics also say it is too open-minded as it allows individuals to bring their own individual frames to the analysis (Borah 2011). But it remains a popular method in political and communication research because of its flexibility and ability to allow researchers to draw meaning from the texts.

Presentation and Analysis of Findings

Our data showed that in The Daily News on Sunday, COVID-19 news stories framed the pandemic not just as a health crisis, but emphasised the governance and corruption frames. There was, in addition to governance and corruption frames, the prevalence of news frames that foregrounded a hopelessly inept government: lacking leadership, with a dysfunctional COVID-19 plan and deliberately driving the nation further into authoritarianism, under the guise of fighting a health pandemic. In The Sunday Mail, the health crisis was framed around two major frames: the containment and responsibility frame, and the mobilisation frame. The containment and responsibility frame was directly opposite to The Daily News on Sunday’s frames. The Sunday Mail emphasised the ability of the government in dealing with the pandemic and its ability to mobilise all sectors of society. Generally, The Sunday Mail’s frames foregrounded the government’s robust and decisive action in fighting the pandemic.

COVID-19 as a Governance and Corruption Crisis

The corruption and governance frames were often juxtaposed in The Daily News on Sunday, and they were characterised by both institutional and individual focus. The paper framed government response to the pandemic as likely to further already existing corruption and mismanagement in the country. The pandemic was framed as bringing to the fore the lack of both transparency and accountability that the ruling party, ZANU-PF, had been accused of perpetuating by opposition political parties, CSOs and NGOs. For example, in an opinion entitled ‘COVID-19: Business Unusual’ (11/04/2020), the paper wrote:

We rely on the goodwill of the international donor community like we always do in most crises…then we have the evil of corruption that is now rooted in ruling party officials’ DNA…Resources will be misappropriated…and there will be outright thievery.

The corruption frame focused on a number of issues such as senior government officials attempting to benefit directly from COVID-19 relief measures especially emergency funds meant for personal protective equipment (PPE). There was also focus on weak institutional governance norms that promoted such corruption: ‘the politicisation of the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission…which has made it unable to fight corruption and root out rot’ (The Daily News on Sunday, 15 June 2020).

The corruption frame generated a ‘sub-frame’ identified as ‘the tampering frame’. This sub-frame emphasised malpractices within government that would militate against functional institutions ready to help fight the pandemic. The tampering frame expressed that the ruling ZANU-PF party would interfere with honest civil servants, which would effectively stymie efforts to fight the pandemic. For instance, in a story with the title, ‘New Twist to US$60m COVID-19’ deal (23/06/2020), the paper wrote:

High ranking civil servants are operating under pressure to approve murky tenders from politically connected people…we saw the massive looting of resources during cyclone Idai…we are back full circle…as the pandemic rages…politicians are busy trying to create feeding troughs for themselves.

Corruption was also framed in metaphorical terms. Metaphors in language discourse allow people to grasp concepts in familiar terms. Corruption was framed in the metaphor of genetics. For example, the paper noted, ‘the evil of corruption that is now rooted in ruling party officials’ DNA’ (emphasis added). In another opinion, corruption was framed in terms of the disease metaphor, as it spread ‘cancerously across the country’s political elites.’ In both cases corruption is presented as endemic and just as one cannot undo their DNA, the metaphor of corruption as engraved in politicians’ DNA means that in Zimbabwe corruption cannot be undone. This is reinforced by the metaphor of corruption as cancerous. This implies that it is, like cancer, incurable, and just like cancer, it spreads fast, and devastatingly so, through Zimbabwe’s body politic, courtesy of ZANU-PF as the ‘vehicle’ in this regard. Due to the cancer of corruption, death by COVID-19 was implied to be certain. The war metaphor was also evoked. In one story: ‘If the government is sincere in its effort to fight the pandemic … it should declare a vicious war against corruption to avoid scarce resources being misappropriated for individual benefit’.

In terms of news sourcing routines, we noted that the corruption frame was buttressed by sources from NGOs, CSOs and opposition political parties’ elites. These sources foregrounded the corruption frame and expressed fear that the government’s plan to fight the pandemic would be useless if there were no corresponding efforts to fight the corruption pandemic. One senior opposition party official was quoted:

Corruption is the second pandemic that will make ZANU PF’s plan to fight COVID-19 useless… like all its other plans coined in the past… resources will be stolen…we all know that bigwigs in the ruling party will enrich themselves. (The Daily News on Sunday, 7 June 2020)

Framing is a form of agenda setting (Gamson 1992). In this case we notice that The Daily News on Sunday attempted to set an agenda of the ruling regime’s corrupt tendencies, its ineptitude, and what we call its customary abandonment of citizens when they need help. For example, its lexical preference of terms like ‘outright thievery’, ‘politicians creating a feeding trough’, is testimony of this. Negative frames can create negative perceptions of the ruling regime, while positive frames can boost popularity of a ruling regime (Jo and Chang 2020). To understand The Daily News on Sunday’s framing preferences, we need to understand two issues. First, its history and then its sourcing routines. The history of The Daily News on Sunday is one of contestation with political power in Zimbabwe (Chibuwe 2016). It was one of the private-owned newspapers that had acted as a public sphere by speaking back to power in an environment which was less tolerant of dissent. Thus, the paper in its coverage of the pandemic pushed this adversarial view about the ruling regime’s efficacy. This is reflected in words like, ‘looting’, and ‘misappropriation’. The paper, hence, assumed a problem definition role in which the ruling regime was seen as part of an enduring problem through examples of terms like, ‘generally corrupt regime’. The middle class of workers and business people were the cornerstone of The Daily News on Sunday readership and advertisers’ base (Ruhanya 2019). This was the same class that had been ‘politically noisy’ and well known for its criticism of the regime. In fact, it was the same class that also formed the political base of support for the opposition. The Daily News on Sunday’s framing of the pandemic, hence, represented the beliefs of the middle class viz-a-viz the regime’s efficiency.

Framing an Inept Political Regime

The Daily News on Sunday, furthermore, framed a ruling party that was hopelessly ill-prepared to fight the pandemic. For instance, the paper took exception with two defence ministry officials over their fake news utterances regarding the pandemic. The Minister of Defence, Oppah Muchinguri, told a ZANU-PF gathering west of the country that COVID-19 was God’s punishment to the USA for imposing sanctions on Zimbabwe. The then Deputy Defence Minister, Victor Matemadanda, wildly added that the COVID-19 was caused by a bacterium, which the West is packaging in small containers, like teargas canisters, to eliminate Zimbabweans. These two statements drew widespread condemnation. The government had to take the rare stance of publicly censuring them. The Daily News on Sunday framed these statements as a culmination of the confusion, and directionless of the regime, supposed to come up with a crisis plan. On 22 April 2020, the paper wrote thus:

It’s hard to imagine that the minister and her deputy sit in cabinet… and they are part of the senior officials supposed to come up with a pandemic plan for this country…This is a national embarrassment…in functioning democracies, the two should have either resigned, or shown the door…but Zimbabwe is not such a country… Our government officials are not even ashamed to display ignorance in public…this is dangerous and life-threatening ignorance.

In another news piece titled, ‘Doctors warn of COVID-19 Implosion’ (17 July 2020), The Daily News on Sunday wrote:

with such people in power, this country is not equipped to fight the pandemic…and chart the future beyond COVID-19. (emphasis added)

The government’s remedies to the pandemic were framed in the paper as ‘going to fail’ because of ‘inept officials occupying senior government positions’ (The Daily News on Sunday, 24 July 2020). There was also an emphasis in the news frames of the point that the ruling regime ‘has long abandoned the poor’. In some of the news stories sampled, the government was framed as an obstacle to other actors who would want to help fight the pandemic. For instance, in an opinion piece titled, ‘The Government must not use COVID-19 to move the country further into authoritarianism’ (4 April 2020), the paper wrote:

There are many actors among NGOs and CSOs, ready to help…but the government’s relationship with these organisations means that there would not be such cooperation…a paranoid regime that is not comfortable with being eclipsed.

It is important to note that The Daily News on Sunday prefers the noun ‘regime’. Regime is often used to refer to a government of an authoritarian nature. The newspaper also foregrounded a chaotic, disastrous and ‘violent’ approach to the pandemic by the government. In an opinion titled, ‘Zim lacks cohesion in fighting COVID-19’ (8 July 2020), the paper foregrounded, through its frames, the chaos rather clearly thus, ‘contact tracing is non-existent…testing and treatment, is still not in motion…what we have seen is the military in the streets…trying to enforce a lockdown…on a battered population’.

Frames of government ineptitude were largely built on the previous frame of corruption discussed. To build this frame, the paper appropriated popular perceptions of a less-caring government (see Al Jazeera, 2020) and popular frustrations with the government’s overall performance (see Al Jazeera, 2020). The government ineptitude frame also thrived on borrowing from history. The newspaper made frequent reference to government’s ineptitude in many other instances of the past. For example, the paper referred to the government’s underwhelming response to Cyclone Idai in 2019 that hit the eastern parts of the country, especially Chimanimani District. Thus, the frame foregrounded a government with a ‘fog of secrecy’, ‘uncooperative’ and used ‘military…law and order approaches’ even during the pandemic. Prevalent discourses under this frame included words like, ‘a clueless government’, ‘messy approaches to the pandemic’ and ‘shambolic COVID-19 plan’. The paper cited NGO and CSO sources that drove the frame forward. Anti-government activists were also cited. And these framed Zimbabweans as:

[The]…victims of the pandemic…who are not likely to get a coordinated response… and reprieve…from the regime.

Noteworthy is that the paper’s frames did not change in the period under study—they remained negative about the ruling regime’s efforts to combat the pandemic. These negative frames were strengthened by the paper’s thematic approach to framing. D’Angelo and Kuypers (2010) note that thematic framing approaches provide a broader and inclusive context to an issue. As in this case, the government’s attempt to address the pandemic was framed within the broad context of its well-documented failures to address previous pandemics of a different nature and its supposedly lack of empathy and efficiency. Thematic framing is the opposite of episodic framing, which focuses on isolated incidences and contexts (Iyengar and Simon 1993). As noted earlier, The Daily News on Sunday always sustained an adversarial relationship with the state. The COVID-19 frames in this paper were broad enough to frame the ruling party’s performance in other areas other than pandemic efforts. Thus, the paper, through its thematic framing approach, made an attempt to frame a regime’s ‘score card of performance’ in all facets of leadership and governance. In the process, broader and contextualised failures of the regime were provided.

News frames according to researchers (Jo and Chang 2020) provide distinctive information and consensus information. Consensus information is about how events can relate to other previous events. For example, the way the pandemic’s efforts are related to previous cholera pandemics of 2008, in The Daily News on Sunday. In 2008 the late former president Robert Gabriel Mugabe was still in power but in 2020 Emmerson Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s long-term right hand until the fall out in 2017, was the president. Upon assuming office on the backdrop of a military coup dubbed ‘Operation Restore Legacy’ in 2017, Emmerson Mnangagwa was installed as the president with the General who orchestrated the coup being appointed vice president. Mnangagwa promised to fight corruption and to break Mugabe’s violent politics and ruinous policies. However, by relating the Mnangagwa’s COVID-19 performance to past-Mugabe regime failures, the Daily News on Sunday was saying the two regimes were the same. Thematic framing by the Daily News on Sunday showed that the paper did not distinguish between the failures of the Mugabe regime and the Mnangagwa regime. It arguably demonstrated that the newspaper considered Mnangagwa’s presidency as simply a continuation of the same old Mugabe regime. This is buttressed by the corruption frame discussed above; it also demonstrates that just like under Mugabe, corruption was still much alive, if not more pronounced under the current regime. The paper also compared the regime’s handling of the pandemic with that of other governments. Conclusively, the idea of comparing was still to expose the regime’s failure in this regard.

Frames in the State-Owned The Sunday Mail

This section explores two prevalent frames in The Sunday Mail: the containment and responsibility frame, and the mobilisation frame.

The Responsibility Frame

This was a prevalent frame in the state-controlled but publicly owned newspaper, The Sunday Mail. The newspaper framed a government that was responsible and in complete control of the unfolding pandemic. For instance, in a story titled, ‘Gvt hailed for its clear COVID-19 strategy’ (24 May 2020), six weeks into the lockdown, the paper wrote:

Experts have hailed the government for its clear strategy in combating COVID-19… The government was praised for coming up with a strategy that will mitigate suffering brought by the pandemic…and arrest the COVID-19 infection rates.

The capabilities of the government were framed in lofty discourses like, ‘hailed …for quick-thinking’, the ‘engaged presidential COVID-19 crisis team’. The responsibility frame carried with it a moral evaluation tone of ‘five-star performance’ on the part of the government. In addition, to framing a responsible government, the weekly paper also framed various institutions of the state and government in rosy terms of efficiency and preparedness. For example, Zimbabwe’s Health Service Board and the President’s Office were hailed for ‘keeping a close eye on the pandemic and the welfare of citizens’ (The Sunday Mail, 5 May 2020). The responsibility for dealing with COVID-19 was, according to the paper, firmly in the hands of the government, which it singled out for praise. And underpinning the responsibility frame was a sub-frame of certainty. The paper was certain that the ruling regime would bring positive change to the pandemic’s destructive effects and that the government’s pandemic plan would work. Expressing its certainty, the paper in one opinion wrote thus:

With stellar leadership that the country has under the second republic of President Mnangagwa, there is no doubt that the country will wither the pandemic storm. Since he ascended the presidency, His Excellency has prioritised people’s welfare…it is even more urgent now.

This sentence, through the use of terms such as ‘stellar leadership’, ‘the second republic of President Mnangagwa’, ‘there is no doubt’, was designed to demonstrate that the Mnangagwa regime was different from Mugabe’s. Mentioning the second Republic was designed to show that under the so-called second republic things would be done differently from the first republic. This was in contrast with the Daily News on Sunday that not only did not make reference to the ‘second republic’ but also created the discourse of an unbroken link between the Mugabe era and the Mnangagwa era. Simultaneously, the paper framed the pandemic as a ‘real’ issue worthy of collaborative action across the broad spectrum of the Zimbabwean society. But in so doing, the paper still foregrounded the government as the major player in whatever collaborative role with other players. In the process, the paper backgrounded all roles that other players would play in the fight against the pandemic. In an opinion titled, ‘Reawakening the human spirit in COVID-19 fight’ (8 June 2020), the paper wrote:

joining hands with the government … heed the government’s call … and pull resources to assist the government … add on to what the government has already mobilised.

The responsibility frame in The Sunday Mail was sustained by a pattern of news sourcing that preferred elite government sources. In most of its stories, the voice of the Minister of Health dominated news sourcing. There was also a preference for senior officials in the ministry as sources of news. The responsibility frame, however, glossed over some more serious concerns of the government’s plan to fight the pandemic. For example, soon after the lockdown was declared on 31 March, a major PPE scandal worth US$60 million allegedly involving members of the president’s own family erupted. The Sunday Mail, however, hid behind its ‘praise and worship’ frames of government effort to ignore the scandal. It only made reference to corruption in a ‘non-committal headline titled, ‘Strengthening transparency, during COVID-19 response’ (9 May 2020). Even the dilapidated public health system of the country was not referenced to. The rosy frames of the newspaper were not in sync with the reality of the Zimbabwean situation.

The Awareness and Mobilisation Frames

These two frames were inter-linked in The Sunday Mail. Under the awareness frame, The Sunday Mail devoted space to alerting the public about the novel virus, placing importance on its symptoms and mode of transmission. The frames that emphasised awareness were often in serious warning discourses. For example, The Sunday Mail wrote about, ‘the public being warned to desist from high contact practices.’ In one opinion titled, ‘COVID-19 upsurge: the second wave or reckless behaviour?’ (5 May 2020), the paper wrote in unusually strong language of awareness:

The public ought to be warned that…this reckless behaviour will lead to more cases…the pandemic is just beginning and we cannot afford a few individuals endangering everyone else…the police should be out in the streets…this is about protecting lives…it simply cannot continue.

The newspaper also stressed in awareness discourses the virus’ mode of transmission and the precautionary and proactive measures that people should take. As much as The Daily News on Sunday carried awareness frames as well, it was eclipsed, in both qualitative and quantitative terms, by The Sunday Mail. For instance, in a detailed op-ed titled, ‘COVID-19 rules work when observed’ (22 June 2020), the paper outlined in detail awareness about the pandemic and what the public should consider immediately to stop the spread:

If we all follow the science…we will defeat the pandemic… be vigilant how we do our business… we are supposed to defeat the pandemic at all costs…washing hands, wearing masks…and maintaining social distance…are all proven ways of beating this pandemic.

In order to raise awareness, the newspaper went further, debunking myths, fake news and ill-founded rumours about the pandemic. In a way, the newspaper check-mated digital platforms that had become notorious for spreading false news during the pandemic. By so doing, The Sunday Mail, in this instance, was living to its expected standard as the ‘fourth estate’.

Closely related to the awareness frame was the mobilisation frame. Under this frame, the government was framed as mobilising society against the pandemic. This was mainly done through Ministry of Health officials who were frequently quoted as sources and whose news supported the mobilisation frame. For instance, the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Health was quoted saying:

As Zimbabweans, we have defeated many foes…this pandemic can be defeated if all of us play a role…I want to appeal to everyone to unite behind the leadership of our president and together we will defeat this pandemic. (8 July 2020)

Government was also framed as successfully mobilising CSOs, NGOs and its various arms for the sole purpose of fighting the pandemic. The mobilisation frame was supported by news sourcing that relied heavily on the president and vice president of the country. The appointment of the vice president Chiwenga to double as the Minister of Health was hailed by The Sunday Mail as part of this mobilisation. In one hard news story (29 July 2020), the paper wrote that, ‘The Vice President’s history of leadership in the military will be important in fighting the pandemic.’

Discussion

The aim of this study was to explore the frames prevalent in the coverage of the pandemic by selected mainstream newspapers in Zimbabwe. Second, the study sought to examine the extent to which this coverage aligned with the biocommunicability model of health news reporting. Four major frames were prevalent: the awareness and mobilisation frames, the responsibility frame, frames of an inept political regime frame, and the corruption frame.

We note that The Daily News on Sunday emphasised episodes of corruption and governance failure in its framing of the pandemic. But The Sunday Mail framed the pandemic along mobilisation and awareness frames that put the ruling regime in very positive light and in control of the pandemic. Such framing, by both newspapers, tended to, an extent, politicise the newsification of the pandemic by linking the pandemic to questions of governance, transparency and accountability. The coverage of the pandemic followed the ideological divisions and polarisation of the Zimbabwean mainstream media that has been well documented in journalism research (Munoriyarwa 2020). The public media have for long been the mouthpiece of the ruling class while the private media have been pro-opposition (Chibuwe 2016). Consequently, in covering the pandemic, the pro-regime media adopted a ‘hear, see and speak no evil’ approach in covering the regime’s pandemic response. It was the ‘sunshine journalism’ approach that framed an infallible ruling regime. Further, it sought to portray the coup regime as better than the previous, however, this was implied rather than explicit. The private media saw a messy approach by a confused and corrupt regime, hopelessly unable to stem the growing tide of the pandemic. It also saw the current regime as a continuation of the incompetent and corrupt Mugabe regime which the leaders overthrew in a military coup in November 2017. Thus, in both newspapers, journalistic norms of objectivity, insisting on the presentation of both sides of an issue, were neglected. The ritual of balance, for example, was not practised as each newspaper practised a news sourcing routine that confirmed its ideological standpoint.

Noteworthy is that the Daily News on Sunday’s Mail’s coverage still synced neatly with the biocommunicability model conceptualised in the theoretical section of this chapter. Their pandemic news facilitated a dialogue about the crisis (Holland 2017). Furthermore, in line with the tenets of the biocommunicability model, the two newspapers still acted as interpretive platforms of the pandemic (see Hall and Meike 2019). Research data supports that this was adopted, to a greater extent, by The Daily News on Sunday. For instance, the paper’s corruption frame opened public debate about related issues of the pandemic—accountable and transparent distribution of resources in the fight against COVID-19. The paper’s corruption frame made a number of generalisations. First, it framed corruption as ‘endemic’ and ‘systemic’. Second, it framed corruption as a permanent feature of Zimbabwe’s post-colonial governance culture, militating against any effort to better people’s lives. Discourses of ‘deep-rooted and widespread corruption’ were prevalent. This, corruption frame reinforced the implied message that there was no difference between the Mugabe regime and the Mnangagwa regime. Thus, in line with the biocommunicability model, The Daily News on Sunday opposed linear conceptualisations of the pandemic that presented an ‘all-saint’ and efficient regime. As the biocommunicability model asserts, health communication should promote public debate and interpret complex health issues and discuss solutions (Holland 2017). Thus, to a larger extent, The Daily News on Sunday’s coverage synced well with this model. Further, the Daily News’ corruption and ineptitude frames were reflective of urban dwellers’ perceptions of government’s handling of previous health crises such as the 2008/2009 cholera epidemic (Chigudu 2019). This stance by the Daily News on Sunday was probably influenced by commercial imperatives since it mainly circulated in the largely pro-opposition urban areas. Indeed, being seen with a copy of The Daily News in certain rural areas invited trouble from ZANU-PF supporters especially during election times.

However, The Sunday Mail’s coverage did not go beyond rudimentary provision of information for survival. It preferred not to open a dialogue about issues of governance, transparency or even critique the government’s pandemic plan. In view of areas of consensus, the findings demonstrated that both newspapers deployed the awareness frame where they sought to raise awareness about the COVID-19 and debunk myths about it as well. The Sunday Mail did more than the Daily News on Sunday both qualitatively and quantitatively in this regard. This is arguably because of its pro-regime stance which meant that it did not want the regime strategy to fail. The consensus could be because COVID-19 does not discriminate between ruling party or anti-ruling party citizens. It infects and kills indiscriminately. The Sunday Mail, however, remained a political mouthpiece of the regime. For instance, despite the widespread condemnation of Oppah Muchinguri’s statement about COVID-19 being a punishment to the USA, the paper did not cover the story. Even the former deputy Minister of Defence’s claim that COVID-19 was caused by bacteria was not debunked in the paper despite these statements being outright example of disinformation.

Both newspapers’ coverage of the pandemic reflected partisan polarisation. And this polarisation was reflected in elite news sources. On the one hand, The Sunday Mail preferred news sources that were pro-ruling party. These included institutional sources of news-especially state-linked institutions, and cabinet ministers or any other top government officials. On the other hand, The Daily News on Sunday preferred news sources from opposition political parties like the MDC Alliance. This sourcing routine reflected media polarisation at an elite level, an enduring feature of Zimbabwe’s media landscape (see Chibuwe 2016; Munoriyarwa 2020). As a result of such sourcing preferences, the two opposing political ideologies became not only manifest in news frames, but equally reinforced. The extent of this polarisation reflected on the levels of partisanship existing in Zimbabwe’s media environment. Having noted these, arguably, the Zimbabwean case, partisan and polarised news framing might have led to increased levels of political gridlocks, disharmony and substantive polarised policy disagreements between the ruling party and the opposition in the parliament. This was already reflected on the offline disagreements between the two on a COVID-19 strategy. The two newspapers selected for this research were adding to this polarisation by presenting unbalanced news frames through their sourcing, lexical and syntactical choices described above. This might have reinforced attitudinal polarisation among readers of the two newspapers, especially on a sensitive and emotive issues like COVID-19 that affect people at personal and familial levels. Nevertheless, this polarisation and partisanship noted in news frames is a part of the agonistic public sphere expected in a media ecosystem. It reflects a robust exchange of ideas among citizens from different political divides.

Conclusion

This research examined how the state-controlled weekly newspaper The Sunday Mail and the privately owned Daily News on Sunday framed the health crisis in the Zimbabwean context. Key findings are that news frames about COVID-19 in the two newspapers tended to reflect the offline political polarisation existing in Zimbabwe. The two newspapers reflected the ideological chasm existing between the ruling party and the opposition. The polarisation, on the one hand, while reflecting a public sphere, albeit an antagonistic one clouded the issue at hand by framing the pandemic as a broad reflection of regime failure. On the other hand, the frames of regime praise in The Sunday Mail equally clouded a non-partisan and fact-based assessment of the regime’s performance in combating the virus. Thus, the unbalanced news frames served a political ideology purpose. Reliance on two newspapers limited the generalisability of the findings to other mainstream newspaper outlets. Future research can add to this research by including a large sample and also include different media platforms like radio and online media.

References

Audit Bureau of Circulation (2018) Global newspapers ABC 2016: a lacklustre final quarter for newspapers. ABC Publication. http://www.auditbureau.org/

Borah P (2011) Conceptual issues in framing theory: a systematic examination of a decade’s literature. J Commun 7(3):246–263

Briggs CL, Daniel CH (2020) Health reporting as political reporting: biocommunicability and the public sphere. Journalism 11(2):149–165

Burgers C, Konijn AE, Steen JG (2016) Figurative framing: shaping public discourse through metaphor, hyperbole, and irony. Commun Theory 26(4):410–430

Chibuwe AL (2016) Language and the (re) production of dominance: Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) advertisements for the July 2013 elections. Crit Arts 31(1):18–33

Chigudu S (2019) The politics of cholera, crisis and citizenship in urban Zimbabwe: ‘People were dying like flies’. Afr Aff 118(472):413–434

D’Angelo P, Kuypers AJ (2010) Doing news framing analysis. Routledge, London

Entman RM (1993) Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun 43(4):51–58

Gamson WA (1992) News as framing: comments on Graber. Am Behav Sci 33(2):157–161

Hall K, Meike W (2019) Whose crisis? Pandemic flu, ‘communication disasters’ and the struggle for hegemony. Health 25:1–17

Hallahan K (2008) Strategic framing. In: The international encyclopedia of communication. Blackwell, Malden, MA

Hart PS, Chinn S, Soroka S (2020) Covid-19 politicization and polarization in COVID-19 news coverage. Sci Commun 42(5):679–697

Holland K (2017) Digital media and models of biocommunicability in health journalism: insights from the production and reception of mental health news. Aust Journalism Rev 39(2):67–77

Iyengar S, Simon A (1993) News coverage of the Gulf crisis and public opinion: a study of agenda-setting, priming, and framing. Commun Res 20(3):365–383

Jo W, Chang D (2020) Political consequences of COVID-19 and media framing in South Korea. Front Public Health 8:425

Munoriyarwa A (2020) So, who is responsible? A framing analysis of newspaper coverage of electoral violence in Zimbabwe. J Afr Media Stud 12(1):61–74

Mutua SN, Oloo Ong’ong’a D (2020) Online news media framing of COVID-19 pandemic: probing the initial phases of the disease outbreak in international media. Eur J Interact Multimedia Educ 1(2):e02006

Ruhanya P (2019) The plight of the private press during the Zimbabwe crisis (2010–18). J Afr Media Stud 10(2):201–214

Shumba K, Nyamaruze P, Nyambuya VP, Meyerweitz A (2020) Politicising COVID-19 pandemic in Zimbabwe: implications for public health and governance. Afr J Governance Dev 9(1.1):270–283

Steele CA, Barnhurst KG (1996) The journalism of opinion: Network news coverage of US presidential campaigns, 1968–1988. Crit Stud Media Commun 13(3):187–209

Thomas T, Wilson A, Tonkin E, Miller ER, Ward PR (2020) How the media places responsibility for the COVID-19 pandemic–An Australian media analysis. Front Public Health 8:483

Vreese CH (2017) Framing as a multilevel process. In: The international encyclopedia of media effects. Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, pp 1–9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Munoriyarwa, A., Chibuwe, A. (2022). ‘This Is a Punishment to America’ Framing the COVID-19 Pandemic in Zimbabwe’s Mainstream Media. In: Dralega, C.A., Napakol, A. (eds) Health Crises and Media Discourses in Sub-Saharan Africa. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95100-9_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-95100-9_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-95099-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-95100-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)