Abstract

Recent studies suggest that being part of a minority group is associated with increased exposure to stress, but what happens if we also account for the effect of religion? This chapter explores minority stress in relation to expectations that religion as capital would positively affect subjective well-being. It is based on the survey data from the project Young Adults and Religion in a Global Perspective. Subjective discrimination and public- and private religious activity are explored in relation to subjective well-being and religious capital. Our data covers a variety of national contexts and allows for an interdisciplinary approach to minority stress theory. The findings suggest that multiple causes of discrimination are associated with lower levels of subjective well-being independent of national context. However, religious capital has different impacts on subjective well-being dependent on national context. The chapter concludes with a reflection on these results, on single and multiple causes of discrimination and the relation to religious capital and suggestions for future research.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Minority stress

- Religious capital

- Subjective well-being

- University students

- Religious practice

- Subjective discrimination

- Depression

12.1 Introduction

In the last 10 years, the relation between religion and health has caught increased scholarly attention. Most studies suggest that being part of a religious community or practicing religion in the form of prayer or reading religious texts have positive effects on subjective well-being (see e.g. Koenig et al., 2012). However, only a few studies have examined religious activities and subjective well-being amongst those minorities and groups who have experienced discrimination, and studies that have addressed this issue are for the most part smaller case studies. This chapter aims to bridge that gap by examining the relationship between subjective well-being, religious capital and perceived discrimination amongst almost five thousand university students distributed over thirteen national contexts.

The analysis expands on previous research on religion and health by exploring whether religion functions as a mediating factor for subjective well-being of university students who have experienced discrimination. Drawing on theories regarding minority stress and religious capital, the aim of the chapter is to examine the relation between subjective well-being and experiences of discrimination, and the role of religious capital for this relation.

It is important to note that the case study design, as well as the focus on university students in the Young Adults and Religion in a Global Perspective (YARG) study, on which this chapter builds, set boundaries for the generalizability of the findings (for more on YARG see Chap. 1 of this volume). We suspect that some of the findings reported in this chapter may be subtler in comparison to a study on young adults who do not have access to higher education. However, a study that explores whether religious capital affects the relation between experiences of discrimination and subjective well-being presents an important contribution to the field. Furthermore, the study distinguishes between university students who have no experiences of discrimination, experiences of discrimination for one cause (e.g. gender, race, religion, sexuality), and those who have experiences of discrimination due to multiple causes. Such a distinction also broadens the scope, as previous studies have not distinguished between experiences of discrimination on single or multiple grounds.

12.2 Previous Research

12.2.1 Religious Engagement as a Source of Religious Capital

Religious capital has been studied mostly in the context of the United States (see e.g. Smidt, 2003) and the United Kingdom (see e.g. Baker & Skinner, 2006; Baker & Miles-Watson, 2008). The notion of religious capital is based on the theory of social capital. James Coleman, one of the key thinkers on social capital, has defined social capital as being “embodied in relations among persons” (1988, p. 118). In Smidt’s book Religion as Social Capital, Smidt does not give a precise definition of religious capital, but describes it as “social capital that is tied to religious life” (2003, p. 211). He builds on the conceptualization of social capital, by including religious life that generates a “particular kind of social capital” (Ibid). Like Coleman (1988), Smidt understands religious social capital as being generated through relations among individuals. His focus is on the production of social capital through religious means, which in this case comprise Christian religious communities in the United States. Smidt argues that in the context of the United States, religious social capital has five particular qualities which differentiate from other forms of social capital (see Smidt, 2003, p. 217–218). Smidt’s argument on the five distinctive qualities are described in positive terms and contrasted to other kinds of social capital, which would be produced through secular sources. However, there is a lack of discussion on the different levels of access to religious capital among members within a congregation. Furthermore, there are no distinctions made between certain religious activities that might provide social capital, such as being part of reading group or maintaining religious practices at home. Finally, Smidt’s focus on Christian communities excludes other religious groups that differ in their public and private practices.

Baker and Skinner (2006) have a more precise conceptualization of religious capital by distinguishing between religious and spiritual capital. Religious capital is the “practical contribution to local and national life made by faith groups”, whereas spiritual capital “is often embedded locally within faith groups but also expressed in the lives of individuals”. (2006, p. 4). Whereas Smidt concentrates on religious communities, Baker and Skinner include how faith expressed through the lives of individuals generates religious capital. Additionally, they include diverse religious communities and emphasize that religious capital cannot be seen as a fixed variable but is “continuously created” (2006, p. 28).

The study presented here aims to contribute to the conceptualization of religious capital with a more diverse approach in two ways. First, religious capital is studied not only in relation to subjective well-being, but also in relation to experiences of discrimination; second, the study explores the role of religious capital independent of religious tradition and national context.

12.2.2 Discrimination on Single and Multiple Grounds and Well-Being

A vast part of the studies that explore the effect of discrimination on well-being is found within minority studies, as reasons for discrimination often relate to a minority position. Studies on minority stress suggest that being part of a minority group is associated with increased exposure to stress (see e.g. Grollman, 2012). Minority stress theory was coined by Meyer (1995), who claims that members of groups who are discriminated against suffer from additional group-specific stressors, which lead to more exposure to stress and, consequently, to “larger health disparities” (Grollman, 2012, p. 200).

Studies on minority stress have suggested that the well-being of an individual who faces discrimination is influenced by whether the discrimination stems from a single cause or from multiple causes. Studies on ethnic minority positions, social capital and subjective well-being (Brondolo et al., 2012; Heim et al., 2011) found that discrimination for a single cause does not always affect subjective well-being. Their study suggests that minority positions may in fact be a mitigating factor for discrimination. Such findings resonate with social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1986/2004) which suggests that threats against a group identity increase group identification and social cohesion (Turner et al., 1984). Individuals who experience multiple forms of discrimination and belong to multiple minority groups may therefore be affected by such experiences in quite different ways. Grollman’s (2012) study on minority stress among young adults revealed that individuals with multiple minority positions experienced higher levels of discrimination, leading to lower levels of both subjective well-being and physical health.

Along similar lines, studies on the role of religion as a factor for discrimination in relation to well-being have rarely taken multiple causes of discrimination into account. After the events of September 11 2001, the well-being of Muslims in Western countries who face discrimination have been addressed in numerous studies (see e.g. Abu-Ras & Abu-Bader, 2008; Jasperse et al., 2012; Jackson & Doerschler, 2012; Brown et al., 2015; Kunst et al., 2012; Rippy & Newman, 2006). On the one hand, these studies show how religious engagement and religious practices were associated with higher levels of subjective well-being, thereby supporting the idea that religious practices and communities can be effective coping strategies (Pargament et al., 2000). On the other hand, Friedman and Saroglou’s (2010) study on immigrant Muslims in Belgium suggested that stigmatization was associated with increased levels of depression and decreased self-esteem, and in contrast to other studies, religiosity did not function as a mitigating factor for decreased self-esteem and depression. They point out that previous studies that have found positive relations between religion and well-being have primarily studied this relation in majority settings, for example, amongst Christians in the United States or Muslims in Muslim countries.

The increasing number of studies on the relation between religion, coping strategies and well-being among sexual minorities (see e.g. Meanley et al., 2016; Shilo et al., 2016; Kiraç, 2016; Jaspal & Cinnirella, 2010) further point to the impact of discrimination on multiple grounds. Sexual minorities often experience discrimination in the religious communities that they are part of and/or face discrimination for being ‘religious’ in ‘secular’ LGBT-communities (Taylor & Snowdon, 2014). Grollman refers to this as a “double disadvantage”, thereby referring to “the double burden” (Collins, 2002) of many “who are disadvantaged on one axis are also disadvantaged on others” (Grollman, 2012, p. 201). Furthermore, in a situation when individuals face discrimination in their own religious communities because of their sexual orientation, and outside their religious communities because of their religious identity, it is far from self-evident that religion and subjective well-being are positively associated (see Meanley et al., 2016).

The studies referred to here have pointed to single or multiple causes of discrimination as an important factor for subjective well-being, which is explored in this study. However, the varying consequences of discrimination found, depending on contextual factors, suggest that consequences of discrimination are difficult to explore in a transnational study. The role of context also suggests that a transnational survey study of discrimination raises questions regarding comparability across case studies, as the questions are likely to be interpreted in different ways in different settings. This study of subjective discrimination through survey research is therefore limited to some degree, as significant contextual differences remain unaddressed and the underlying interpretations of respondents remain unattainable.

12.2.3 Religious Capital and Subjective Well-Being

The relation between religion and subjective well-being has been thoroughly explored in previous studies, albeit without using the concept of religious capital. For example, studies have investigated the relationship between subjective well-being and spirituality and religiosity (see e.g. Yonker et al., 2012). In general, in studies done on these themes, components that would relate to religious capital would be measuring the identification of one with a religious community , participation in activities within a community, private religious practices and how someone relates decisions to his or her religious identity. These dimensions are frequently found in studies on religion and subjective well-being, and in line with studies on social capital and subjective well-being. Most studies suggest a positive association between religion and subjective well-being (see e.g. Koenig et al., 2012 on religion and health). Not only does religiosity protect against ‘risk behavior’ (drugs, unprotected sex), but it has also been associated with fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety (Smith & Snell, 2009; Yonker et al., 2012).

However, some studies contradict the positive effect of religion on subjective well-being. Exline et al. (2000) found that religious strain among college students is associated with greater depression and suicidality, regardless of religiosity levels or the comfort found in religion. Bryant and Astin (2008) confirm these findings in their study on college students, as they found an association between struggling with faith and lower levels of self-esteem, poorer physical health and greater risks for engaging in addictive behaviors. These findings challenge the positive associations found between religiosity and subjective well-being, and confirm that struggling with one’s own religious identity as a young adult could potentially lead to a decrease in subjective well-being.

Studies with an intersectional approach also point to varying relations between religion and subjective well-being. For instance, when studying the influence of religion, religiosity and spirituality on mental health among Indian young adults, Ganga and Kutty (2012) found differences in subjective well-being depending on the gender and the religious tradition of the participant. Such differences were explained by “behavioral restrictions and opportunities for socialization that religion does or does not provide” (2012, p. 435).

This section has highlighted that religious capital has predominantly been studied in a Western context, which points to the usefulness of studying this concept further in a transnational study such as this one. In addition, the overview demonstrates that while religious capital has been operationalized in various ways in previous studies, engagement in religious communities nevertheless could be regarded as a criterion for religious capital to be generated. Finally, just as for discrimination, gender reoccurs here as a factor having an impact on subjective well-being. For both of these issues, it seems as if gender is a contributing factor that may both result in increased and decreased well-being depending on how it is combined with other background factors. Previous research therefore suggests that gender must be properly taken into account in the study of how religious capital contributes to the relation between discrimination and subjective well-being.

12.3 Purpose and Research Questions

The aim of this chapter is to explore the relationship between subjective well-being, religious capital and those participants who report belonging to a group that faces discrimination. The main purpose of the chapter is therefore not to explore subjective well-being per se, but rather to understand subjective well-being in light of a number of background factors (subjective single or multiple discrimination, gender, national context). Based on previous research, we are particularly interested in exploring how subjective well-being is interrelated with religious capital and in light of personal experiences of discrimination.

The above-mentioned aim results in the following research questions:

-

1.

How common are experiences of discrimination amongst the participants of Young Adults and Religion in a Global Perspective?

-

2.

a. Do young adults report different levels of subjective well-being depending on whether they have experienced discrimination or not?

b. Does the number of causes reported (single-multiple) influence the role of experiences of discrimination on subjective well-being?

-

3.

What is the role of religious capital for subjective well-being amongst those who have experienced discrimination?

-

4.

Does this role vary depending on other background factors such as gender and national context?

12.4 Measures

12.4.1 Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being was measured as a composite measure mapping dimensions of general well-being and happiness, vitality, depression, life orientation and peace of mind. General well-being and happiness were measured through three questions,Footnote 1 vitality as a mean of five items,Footnote 2 depression as a sum of eight items,Footnote 3 and life orientation as a mean of four items.Footnote 4 The respondent’s peace of mind was measured through two questions.Footnote 5

The composite measure of subjective well-being was created through a series of steps. Since responses on the included items were not made on the same scale, all items were initially standardized, and afterwards, a sum value of all items was obtained for each respondent as a measure of personal well-being. In the second step, individual values on well-being were sorted according to a national case study, and the means for each national case study were standardized in order to obtain a global measure for subjective well-being, where the proximity to zero indicates proximity to the mean value of subjective well-being for the total sample. This procedure makes it possible to compare case studies in relation to the global mean for subjective well-being.

For the first analysis, all variables were measured together to represent subjective well-being and separately to look into differences between for example depression and life satisfaction. For the second analysis, all variables were measured together to represent subjective well-being for the total sample and the three separate country cases.

12.4.2 Discrimination

Experiences of discrimination were mapped through the following question: “Would you describe yourself as being a member of a group that is discriminated against in the country you live in now? Please, select all that apply”. The participant can then tick from multiple boxes, which include: “No, I don’t feel discriminated against”, “Color or race”, “Nationality”, “Religion”, “Political orientation”, “Language”, “Ethnic group”, “Age”, “Gender”, “Sexuality”, “Disability”, “Other, please, describe”.

In line with minority stress theory , distinctions are made between young adults who have reported experiences of discrimination depending on whether they have reported single or multiple causes for this discrimination. The selection criteria of participants for the analysis is based on the question on discrimination (N = 4956)Footnote 6 (which includes discrimination against color or race, nationality, religion, political orientation, language, ethnic group, age, gender, sexuality, disability). Students who do feel that they belong to a group that is discriminated against are divided between either single discrimination (students who reported discrimination due to one cause, N = 909) and multiple discrimination (students who reported discrimination on multiple grounds, N = 931).

12.4.3 Religious Capital

Religious capital was measured through two questions on religious practice : Public practice was operationalized through the question “Apart from special occasions such as weddings and funerals, about how often do you take part in religious ceremonies or services these days?”. Private religious activity was mapped through the following question “Apart from when you are at religious ceremonies or services, how often do you engage in private religious or spiritual practices, such as worship, prayer or meditation?”. Responses were made on a six-grade ordinal scale, ranging from “Every day” to “Never” as well as the alternative “I don’t know”. Participants who responded “I don’t know” (N = 142) were excluded in the final analysis on the three case studies.

12.4.4 Statistical Tests

The first research question regarding the commonality of experiences of discrimination is presented in the form of two frequency tables, where experiences of discrimination are reported according to case study (Table 12.1) and gender (Table 12.2). The interaction between experiences of discrimination and national context and gender respectively were explored through multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests.

The second research question, which concerns whether experiences of single and multiple forms of discrimination are associated with differences in subjective well-being, is explored through a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) analysis.

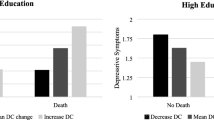

As the findings pointed to great diversity between the national case studies, the third research question about the interaction between subjective well-being, discrimination and religious capital was studied further in three national case studies. Two case studies represent the national context in which experiences of discrimination were found to be the most and least common, and a third case study was added since it corresponded to the average of experiences of discrimination in the total sample. For each of these case studies, the interaction between subjective well-being, single and multiple discrimination, and religious capital were studied through a regression analysis. The two measures of religious capital constituted independent variables in the analysis, and furthermore, gender and experiences of discrimination were introduced as dummy variables (both single discrimination and multiple discrimination are compared to the “no discrimination”-group). For all three case studies, two regression analyses using different dependent variables were conducted: the first one uses the global measurement of subjective well-being as the dependent variable, while the other model used the indicators of depression as its dependent variable, thereby analyzing one potential symptom of lack of well-being. In these regression models, a higher score on subjective well-being means higher well-being, while higher scores on depression mean more symptoms of depression.

The fourth research question about the role of gender and national context is explored throughout the analyses conducted in relation to the other research questions.

12.5 Findings

12.5.1 Experiences of Discrimination Amongst University Students

For the first statistical analysis, all participants of the survey (N = 4956) were divided into three groups: those who responded that they did not feel discriminated against; those who mentioned having been discriminated against for one cause, and those who reported discrimination against for several causes. As demonstrated in Table 12.1, a majority (63%) has replied that they do not feel discriminated against. Those who acknowledge experiences of discrimination are evenly divided between having been discriminated for one single cause and having been discriminated for at least two causes. When responses are broken down into national case studies, response patterns vary significantly. For example, almost nine out of ten Polish respondents report no experiences of discrimination, whilst in Turkey, the corresponding proportion is only 36%. The analysis according to national context indicates that the lower the proportions of no discrimination in a national case study are, the higher are the proportions of respondents that report having experienced multiple causes of discrimination. Experiences of one single cause of discrimination do not follow such patterns, but vary between countries.

While Table 12.1 indicates that subjective discrimination is more common in some national contexts than in others, the table does not provide any easy explanation for this internal variation. Rather, a closer reading of Table 12.1 raises questions about the reasons for this internal variation, and why this question has evoked such different responses in different countries. Experiences of gender discrimination are, for example, not only bound to vary depending on social context, but also, due to different understandings regarding what gender discrimination entails. In this way, high proportions of gender discrimination could both imply the commonality of experiences of sexism and/or high awareness of sexism. These different reports on experiences of gender discrimination are a consequence of reporting subjective discrimination. The proportions reported in Table 12.1 should therefore be interpreted with great caution, as this reasoning suggests that we cannot assume that the question has been answered in similar ways regardless of national context.

While we refrain from going into a deeper analysis regarding the group memberships that experiences of discrimination are associated with at a national level, gender is by far the most common cause of discrimination, albeit a much more common experience amongst female respondents than amongst male respondents. Experiences of discrimination due to religion, language group, political orientation, ethnicity , nationality and color or race are shared by between 5% and 10% of the respondents. Experiences of discrimination due to sexuality, age or disability are less common (around or below 5%). When we divide experiences of discrimination by gender, it seems as well that gender is a contributing factor, as 41.3% of the female respondents experiences single or multiple discrimination compared to 30.4% of the male respondents (see Table 12.2). Respondents who identified as other (N = 25), experienced the highest amount of discrimination, with only three respondents reporting no experiences of discrimination, three reporting single cause discrimination and 19 reporting multiple causes of discrimination.Footnote 7

In light of this data, we therefore proceed to focus on three case studies in the subsequent analysis, due to their varying experiences of discrimination. Poland is selected since the proportions of discrimination reported amongst the respondents are the lowest out of all case studies, and since Turkey is characterized by the opposite, Turkey is also selected as a second study. Finally, Peru is selected as a third case study for further analysis, since the experiences of discrimination amongst the Peruvian respondents lie close to the total average of the respondents. By studying the interaction between religious capital, discrimination and well-being in these three countries, we can come one step closer to understanding whether the relations by these factors that are suggested in previous research hold true regardless of how common experiences of discrimination are. However, before this final step, we conduct a further analysis on subjective well-being and discrimination.

12.5.2 The Role of Discrimination for Subjective Well-Being

In this section, differences in subjective well-being are compared in three categories of participants: those who experienced no discrimination, and those who have experienced single or multiple forms of discrimination respectively. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted, where the dimensions of subjective well-being were introduced as dependent variables, and discrimination and country respectively as independent variables. Using Pillai’s trace, the main effects of discrimination and country respectively were found.Footnote 8

After having established the main effect of discrimination on subjective well-being, eight independent analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were conducted in order to test whether the different dimensions of subjective well-being that were included in the measure interacted differently with the three discrimination categories. As demonstrated in Table 12.3, these analyses revealed significant differences in subjective well-being depending on experiences of discrimination, regardless of the dimension measured. Participants who reported experiences of discrimination felt overall less satisfied with their life, less happy, more depressed, less energized, more anxious and less peaceful and calm compared to participants who had not experienced discrimination. Furthermore, there were significant differences in subjective well-being between the categories of single or multiple causes of discrimination, except for the measures of satisfaction regarding standard of living and life orientation.

The previous analysis suggests that in the total sample, experiences of discrimination are negatively associated with subjective well-being. While this confirms the negative impact of discrimination on subjective well-being and the increase of impact when there are multiple causes of discrimination, broadly referred to as minority stress theory (Meyer, 1995; Grollman, 2012), this analysis does not include the role of religious capital, which is yet to be introduced into the analysis. Furthermore, bearing in mind the case study differences reported in Table 12.1 and the issues of validity that these findings seem to entail, we now turn to regression analyses where religious capital is included in three selected case studies, characterized by different amounts of reported discrimination.

12.6 The Effect Between Religious Capital and Discrimination on Subjective Well-Being and Depression in Poland, Peru and Turkey

We now continue with the analysis of the relation between discrimination, subjective well-being and religious capital in three of the case studies. As Table 12.1 reflects, the included national case studies in YARG were characterized by varying amounts of experienced discrimination. In order to test the assumptions regarding the relations between discrimination and subjective well-being and the role religious capital has in this equation, these assumptions should hold regardless of how (un-)common experiences of discrimination are in a national context. We therefore explore these relations in three case studies that were characterized by high, low, and average amounts of subjective discrimination.

12.6.1 Poland

As a next step, we analyze the interaction between subjective well-being, discrimination and religious capital in a country where subjective experiences of discrimination are relatively rare. Out of all case studies, Poland was the country where experiences of discrimination were most uncommon. As previously stated, 88% of Polish respondents report that they do not belong to a group that experiences discrimination; 8% mention being discriminated for one cause, and 4% for multiple causes. Polish women report less experiences of discrimination than Polish men (90% of women who do not belong to a group that experiences discrimination and 85% of men respectively; N = 299).

To continue, we turn to the findings from regression analyses that examine the role of public religious practice, private religious practice, gender and experiences of discrimination on subjective well-being. Table 12.4 reports the findings from two analyses: one where subjective well-being constitutes the dependent variable, and one where depression constitutes the dependent variable. The analysis on depression serves as a control analysis in order to ensure that the findings from the analysis regarding subjective well-being correspond with the analysis where symptoms for depression constitute the dependent variable. For this reason, the discussion of the findings focuses on the analysis concerning subjective well-being.

Table 12.4 reflects that public religious practice, private religious practice, gender and experiences of discrimination explain 10% of the variation in subjective well-being in the Polish sample. As this means that approximately 90% of subjective well-being is explained by other variables than those which we have in our models, the explanatory power of this model is quite modest.

Out of the factors measured, experiences of discrimination on multiple grounds have the strongest negative effect on subjective well-being, followed by being male and reporting discrimination on one cause. This means that experiences of discrimination and being male is associated with lower subjective well-being than having no experiences of discrimination and being female, but not to the same extent as experiences of discrimination on multiple grounds do. The measures of religious capital (public and private religious practice ) indicate that religiosity appears to have a negative effect on well-being in the Polish case study, but the effect of public and private religious practice is quite small and non-significant.

The analysis that explores the role of religiosity, gender and discrimination for depression corresponds with the findings supported above, but the explanatory power of the regression model is even lower – 8% – than for the model where subjective well-being constitutes the dependent variable, which explained 10% of the variance. The even more modest explanatory power on behalf of the second analysis suggests that the measure of subjective well-being is more robust a construct than depression as a single variable.

12.6.2 Turkey

Out of all case studies, the participants from Turkey reported the most experiences of discrimination (N = 344), as only a little more than one-third (36%) report no experiences of discrimination, meaning that two-thirds report having experienced either single or multiple forms of discrimination. A closer look reveals that the total distribution reflects the experiences of female Turkish participants to a higher extent than Turkish males, due to the female over-representation in the Turkish case study and their experiences of discrimination. Out of the female respondents, 71% report experiences of discrimination, and most often, on multiple grounds (46%): the corresponding figure for male respondents is 49% (out of which 29% on multiple grounds). Even if the experiences of discrimination amongst male respondents are less common than for women in Turkey, the distribution for male Turkish respondents also places them amongst the most discriminated out of all case studies in YARG.

As we turn to the regression models and how they account for the level of subjective well-being in Turkey (Table 12.5), we notice that the included measures explain merely 5% of subjective well-being, which is low. Out of the included measures, only the experiences of single and multiple discrimination are statistically significant. Both of these measures have a negative effect on subjective well-being, and the effect of having experienced discrimination for one cause is surprisingly stronger than for discrimination on multiple grounds. In Turkey, where experiences of discrimination are relatively common, such experiences are also found to have a negative effect on subjective well-being, but contrary to the theorizing that underlined the model, those who experience discrimination on multiple grounds do not report lower subjective well-being than those who experience discrimination for one cause.

It is also worth noting that the model in which depression constitutes the dependent variable has exceptionally poor explanatory power: only 0.5% of the variance in reported symptoms of depression is explained by the variables included in the model. In line with such findings, none of the included variables have a statistically significant ability to explain variations in indications of depression in the material.

12.6.3 Peru

Peru constitutes the third case that we chose to explore further, this time because of the non-exceptional character of the Peruvian case study. Peru is one of the case studies in greatest proximity to the average of experienced discrimination of the total sample. In numbers, this means that 59% report no experiences of discrimination, 21% experiences due to one cause, and 20 report experiences of multiple causes of discrimination (N = 319). Female and male experiences differ, as female Peruvians report more discrimination than males: while one-tenth of males report experiences of discrimination on multiple grounds, the corresponding number for females is 24%. The experiences of discrimination for one cause are quite similar (females: 22%; males 19%). Consequently, seven out of ten Peruvian males report no experiences of discrimination – the corresponding number for females is 54%. Therefore, we include Peru as a case that represents the middle ground as far as experiences of discrimination go, and explore explanatory factors for subjective well-being in Peru.

In the Peruvian case study, we find that many of the included factors in the regression model have a statistically significant effect on subjective well-being. Multiple discrimination and being male are the factors that have the strongest explanatory power, both affecting subjective well-being in a negative direction. Furthermore, public religious practice has a positive but not very strong effect on subjective well-being in Peru. Private religious practice and discrimination due to a single cause were found to have no significant effects on subjective well-being. While the statistical findings attest to the validity of the measures included in the model, the model’s total capacity to account for the variation of subjective well-being is only 9%, which is quite modest.

For the Peruvian case study, the regression model where depression constitutes the dependent variable is equally strong in terms of variance explained, but the way in which single measures (see Table 12.6) contributes to depression varies. Public religious practice has no statistically significant effect on depression: instead, multiple discrimination and being female (rather than male) are both related to a higher propensity to report symptoms of depression. In other words, multiple discrimination lowers subjective well-being and contributes to depression, but whereas being male appears to contribute to lower subjective well-being, being female seems to contribute to reporting more symptoms of depression.

12.7 Conclusion

Throughout this chapter, the relationship between subjective discrimination, subjective well-being and religious capital has been examined. The underlying assumptions behind minority stress theory and religious capital are further explored in light of these results in relation to the research questions in this conclusion.

The results of the first research question, namely how common experiences of discrimination amongst the YARG participants are, demonstrated that globally a majority (63%) did not belong to a group that is discriminated against. However, when national context was included as a variable (see Table 12.1), it shows that subjective discrimination is more common in some national contexts than in others. Despite these differences, because the survey reports subjective discrimination, it is unknown what these differences entail. Therefore, the analysis is limited to the categories of no, single or multiple causes of discrimination, as further interpretations of survey answers are unattainable. The first analysis does demonstrate an increase in multiple causes of discrimination in case of higher levels of single discrimination.

The first part of the second research question (2a); do young adults report different levels of subjective well-being depending on whether they have experienced discrimination or not, is found positive in our analysis. Regardless of the dimensions of subjective well-being that were measured, there were significant differences in subjective well-being related to experiences of discrimination. This finding suggests that experiences of discrimination are negatively associated with subjective well-being.

The second part of the second research question (2b), does the number of causes reported (single-multiple) influence the role of experiences of discrimination on subjective well-being, was found positive as well. We found a significant effect of discrimination on subjective well-being which revealed that those experiencing multiple discrimination had lower levels of subjective well-being than those experiencing single discrimination or no discrimination. Our findings suggest that experiences of discrimination are negatively associated with subjective well-being and that experiences of discrimination on multiple grounds is related to lower levels of subjective well-being globally.

The analysis on the different dimensions of subjective well-being showed that there were significant differences on the impact of subjective well-being between the categories of single or multiple causes of discrimination. In comparison to single cause discrimination, multiple causes resulted in a further decrease of subjective well-being on all components measured, except life orientation and satisfaction regarding standard of living. These results align with minority stress theory ; people who are exposed to multiple causes of discrimination because they belong to a group that is discriminated against, face larger health disparities than those who face single cause discrimination or no discrimination.

The third research question; namely what is the role of religious capital for subjective well-being amongst those who have experienced discrimination, was explored through three different case studies that exemplified the lowest (12%), the highest (64%) and the average (41%) cases of respondents who experienced discrimination in the whole of the material: Poland, Turkey and Peru. The role of religious capital for subjective well-being amongst those who have experienced discrimination was different in all three of the case studies. The explanatory power of the included variables (discrimination, religious capital, gender) was in all three of the case studies modest. Only in one out of the three case studies, Peru, was a significant effect found which indicates that public religious practice has a slightly positive effect on subjective well-being.

The final research question, does the role of religious capital for subjective well-being amongst those who have experienced discrimination vary depending on other background factors such as gender and national context, was found positive as well. As the different results in the final analysis on the three separate case studies showed, national context and therefore different religious practices have different effects on subjective well-being. However, gender as a factor did not come across as a convincing factor with independent explanatory power in the regression analysis on the three case studies. These findings show on the one hand how national context is of importance and on the other how other variables than gender and national context should be included to explore the different results per case study.

To conclude, this chapter has illustrated three main things. First of all, for future quantitative studies on subjective well-being in relation to discrimination on a global scale, the variable of subjective well-being is more reliable than other measures such as depression. Secondly, the findings of the analysis have illustrated the complication of understanding the concept of discrimination in a global quantitative study through the same question. All the three cases gave different results through regression models. Even though the first global analysis confirms minority stress theory , when we examined separate case studies in different national contexts, subjective discrimination became complicated to understand and to compare. Finally, theories on subjective well-being are underlined by the idea that while subjective well-being is most likely achieved in different ways depending on cultural context, the outcome (estimated subjective well-being), should be the same regardless of cultural context. Our findings point the other way, which complicates the measurement of subjective well-being, discrimination and religious capital. This complication emphasizes the importance of more qualitative studies on religion, subjective well-being and discrimination in case studies that involve minority groups, which could further enhance the conceptualization of religious capital and give insights into the role of religion on the subjective well-being of young adults who experience discrimination.

Notes

- 1.

“All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole nowadays?”, “Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are?” “How satisfied are you with your present standard of living?” (E1-E3).

- 2.

How much of the time during the past week… You had a lot of energy? You felt tired? (reversed) You were absorbed in what you were doing? You felt bored? (reversed) You felt really rested when you woke up in the morning? (E5.9, E5.11, E5.12, E5.14, E5.15).

- 3.

How much of the time during the past week… You felt depressed? (reversed) You felt that everything you did was an effort? (reversed) Your sleep was restless? (reversed) You felt happy? You felt lonely? (reversed) You enjoyed life? You felt sad?” (reversed) (E5.1–8).

- 4.

“I’m always optimistic about my future.” “In general I feel very positive about myself.” “At times I feel as if I am a failure.” (reversed) “On the whole my life is close to how I would like it to be.” (E4).

- 5.

How much of the time during the past week… You felt anxious? You felt calm and peaceful? (E5.10, E5.13).

- 6.

Participants who reported discrimination on all grounds are excluded from the analysis, n = 8.

- 7.

Due to the low number of respondents identifying as other in total number of respondents, they were left out in Table 12.2 to be represented in percentages.

- 8.

Discrimination: (V = 0.02, F(8, 1807) = 4.40, p < .001); country (V = 0.47, F(96, 14,512) = 9.40, p < .001).

References

Abu-Ras, W., & Abu-Bader, S. H. (2008). The Impact of the September 11, 2001, Attacks on the Well-Being of Arab Americans in New York City. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 3(2), 217–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564900802487634

Baker, C., & Miles-Watson, J. (2008). Exploring Secular Spiritual Capital: An engagement in religious and secular dialogue for a common future? International Journal of Public Theology, 2(4), 442–464.

Baker, C., & Skinner, H. (2006). Faith in action: The dynamic connection between spiritual and religious capital. William Temple Foundation.

Brondolo, E., Libretti, M., Rivera, L., & Walsemann, K. M. (2012). Racism and social capital: The implications for social and physical well-being. Journal of Social Issues, 68(2), 358–384.

Brown, L., Brown, J., & Richards, B. (2015). Media representations of Islam and international Muslim student well-being. International Journal of Educational Research, 69, 50–58.

Bryant, A. N., & Astin, H. S. (2008). The correlates of spiritual struggle during the college years. The Journal of Higher Education, 79(1), 1–27.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

Collins, P. H. (2002). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Exline, J. J., Yali, A. M., & Sanderson, W. C. (2000). Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(12), 1481–1496.

Friedman, M., & Saroglou, V. (2010). Religiosity, psychological acculturation to the host culture, self-esteem and depressive symptoms among stigmatized and nonstigmatized religious immigrant groups in Western Europe. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 32(2), 185–195.

Ganga, N. S., & Kutty, V. R. (2012). Influence of religion, religiosity and spirituality on positive mental health of young people. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16(4), 435–443.

Grollman, E. A. (2012). Multiple forms of perceived discrimination and health among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(2), 199–214.

Heim, D., Hunter, S. C., & Jones, R. (2011). Perceived discrimination, identification, social capital, and well-being: Relationships with physical health and psychological distress in a UK minority ethnic community sample. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(7), 1145–1164.

Jackson, P. I., & Doerschler, P. (2012). Benchmarking Muslim well-being in Europe: reducing disparities and polarizations. Policy Press.

Jaspal, R., & Cinnirella, M. (2010). Coping with potentially incompatible identities: Accounts of religious, ethnic, and sexual identities from British Pakistani men who identify as Muslim and gay. British Journal of Social Psychology, 49(4), 849–870.

Jasperse, M., Ward, C., & Jose, P. E. (2012). Identity, perceived religious discrimination, and psychological well-being in Muslim immigrant women. Applied Psychology, 61(2), 250–271.

Kıraç, F. (2016). The role of religiosity in satisfaction with life: a sample of Turkish gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 63(12), 1594–1607.

Koenig, H., Koenig, H. G., King, D., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oup Usa.

Kunst, J. R., Tajamal, H., Sam, D. L., & Ulleberg, P. (2012). Coping with Islamophobia: The effects of religious stigma on Muslim minorities’ identity formation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(4), 518–532.

Meanley, S., Pingel, E. S., & Bauermeister, J. A. (2016). Psychological well-being among religious and spiritual-identified young gay and bisexual men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(1), 35–45.

Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 38–56.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(4), 519–543.

Rippy, A. E., & Newman, E. (2006). Perceived religious discrimination and its relationship to anxiety and paranoia among Muslim Americans. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 1(1), 5–20.

Shilo, G., Yossef, I., & Savaya, R. (2016). Religious coping strategies and mental health among religious Jewish gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(6), 1551–1561.

Smidt, C. E. (Ed.). (2003). Religion as social capital: Producing the common good. Baylor University Press.

Smith, C., & Snell, P. (2009). Souls in transition: The religious and spiritual lives of emerging adults. Oxford University Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (Original work published 1986) (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

Taylor, Y., & Snowdon, R. (Eds.). (2014). Queering religion, religious queers. Routledge.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Turner, P. J., & Smith, P. M. (1984). Failure and defeat as determinants of group cohesiveness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 23(2), 97–111.

Yonker, J. E., Schnabelrauch, C. A., & DeHaan, L. G. (2012). The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence, 35(2), 299–314.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Meijer, C.M., Klingenberg, M., Lagerström, M. (2022). On the Subjective Well-Being of University Students: Religious Capital and Experiences of Discrimination. In: Nynäs, P., et al. The Diversity Of Worldviews Among Young Adults. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94691-3_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94691-3_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94690-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94691-3

eBook Packages: Literature, Cultural and Media StudiesLiterature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)