Abstract

When confronted with being asked to “draw god”, children have to solve a problem; they are being asked to produce a visual representation of an entity that they have never seen. Resources for solving this problem are available within the child’s cultural context: The shape of the figure itself may be based on various religious representations of gods, iconic figurations of supernatural agents in fictional artefacts (paintings, movies, cartoons even in advertisement), various valences may be attributed to colours or to different parts of an image composition, etc. The drawings produced by children depend also on their cognitive abilities to grasp the concept of god, their emotional abilities to express the accompanying feelings, their creativity and artistic skills. In representing god, children have to solve additional problems. For example, connotations of the concept of god can awaken attachment bonds to parental figures; religious prohibitions against representations of god can be in conflict with the task of drawing god. The purpose of this work is to integrate the results presented in parts II-V of this book, and to articulate the different factors in an integrated model that outlines possible strategies used to carry out the project of drawing god.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Child development

- God representations

- Drawings

- Religious education

- Socio-cultural influence

- Cross-cultural

- Gender

- Anthropomorphism

- Emotionality

- Visual research

“Have you ever heard the word godFootnote 1? Try to imagine and draw it.” The task can be puzzling. How is it possible to draw something or somebody that I have never seen? A person receiving this instruction might think: “It is as if I had to draw the infinity, hope, or the emptiness!” That is right, but just because someone has never seen the infinity, hope, or the emptiness, does not mean that the person is unable to draw them. It is not always necessary to have seen what we want to draw. We always have the opportunity to let our imagination gallop, and put colours and lines on a sheet of paper, following our fantasy.

Here, however, there is a complication. I am being asked to draw god—not just something that I can imagine. People who look at my drawing should be able to recognize that it represents (a) god. My drawing should refer to a concept expressed by the word god.

In some sense, the task of drawing god could be considered an impossible task. Nevertheless, when children are asked to draw god, very few of them say that it is impossible. They find a host of ways, borrowed from the ambient culture or fruit of their creativity, to provide drawings of god(s). The drawings they create inform us about their understandings of the concept of god, their familiarity and relation to it, and the solutions they have employed to accomplish the requested task. Several chapters of this book describe this phenomenon from different vantage points; this chapter tries to integrate these perspectives.

Outline of the Presentation

We will begin with the role of anthropomorphism in the representation of god. It is commonly said that god representations of young children are more anthropomorphic than those of older children or adults. The psychological development from childhood to adulthood is undoubtedly an axis on which we can observe modifications in the treatment of anthropomorphism in divine representations. Nevertheless, the reason for anthropomorphic features in the representation of living beings or supernatural agents, including gods, is not only a result of development, but also the result of cognitive functions. We tend to attribute the properties of what we know to what we do not know. Piaget spoke of this process as assimilation.

For this reason, we will begin the presentation by discussing the role of anthropomorphism in the representation of supernatural agents. We will then situate the products of this discussion in a developmental perspective: how do children and adolescents (6–16 years old) manage this question of anthropomorphism when it comes to representing a god?

Then, because most of the anthropomorphic features have gender connotations and because these features and connotations are shaped by culture, the presentation of our integrative model will continue by incorporating these two additional perspectives. We will first discuss the gender aspect: How do children manage the attribution of gender in the treatment of anthropomorphism in the drawing of god(s)? Do they conceptualize god as masculine, feminine, neutral, or a combination of masculine and feminine features? Further, what does the expression of gender tell us about how the children relate to the representations proposed to them by their cultural context?

At this stage of the presentation, we will not yet have moved beyond the conceptual level. Our model will stand temporarily limited to the integration of four perspectives that influence the understanding and thus the representation of the concept of god: the cognitive, developmental, gender, and cultural perspectives.

However, the factors that influence the manner in which children draw god are not only located on the conceptual level. That is why we enrich the model by considering the emotional and affective perspectives. Drawing god does not have to be merely an act of transmitting informative knowledge about a concept. Drawing also offers the opportunity to express emotions that reflect the relation between the artist and what he or she is drawing. For this reason, we will continue the presentation of the integrative model by considering, in succession, the relational aspects of attachment and emotionality in the drawings of gods. We also consider the manner in which these two additional perspectives (attachment and emotionality) relate to the four we had considered on the conceptual level (cognitive, developmental, gender, and cultural).

Finally, we will add the educational level, which refers to religious socialisation. If the artist has only a vague connection with discourses and context where “god” is mentioned, emotionality in his or her drawing will probably not be very high. For that reason, we integrate a supplementary perspective, religious education, into the model. This perspective identifies the intensity of religious socialization and formal religious education in the form of courses at school or in the religious community. At this stage of the presentation, we will also discuss the influence of religious education on the other aspects (anthropomorphism, gender, conformity to religious or cultural representations).

In conclusion, we will highlight one transversal feature that can be observed on the cognitive-conceptual level, and on the attachment and emotional levels: ambivalence. God images, god concept, and more generally god representation seem predisposed to be ambivalent. We will present arguments to explain this observation, and conclude with some synthetic remarks.

Definitions

In this chapter, the term god concept will be used to refer to the more cognitive understanding of god, while the god image refers to experiential views of god which are more affect-laden and partly function on an unconscious level. God representation is the umbrella term which comprises both god concept and god image (Hall & Fujikawa, 2013; Davis et al., 2013).

Anthropomorphism in the Representation of Gods: Cognitive and Developmental Perspectives

In a text published in 2001, Justin Barrett tries to answer the question “Do children experience God as adults do?” In this text, he begins by describing what he calls the “standard anthropomorphic-to-abstract shift”. Citing several developmental psychologists (e.g., Goldman, 1964; Heller, 1986), he summarizes the dominant paradigm of the development of god concepts as “a radical shift from crudely anthropomorphic concepts in childhood to the dizzyingly abstract concepts of adulthood” (Barrett, 2001, p. 174). In doing so, Barrett attributes to Piaget the paternity of this developmental paradigm, pretending that Piaget has exposed these ideas in The Child’s Conception of the World (1929).

This is a misunderstanding from several points of view. First, Piaget never published a text on the development of the representation of God in children. Second, he does not insist on the anthropomorphic character of the God concept in children. Third, he does not use the opposition between concrete and abstract to describe the evolution of the representation of God in children. Let us take these three points one by one.

First of all, in his prolific career, Piaget never took the time to devote a writing to the representation of God by children. Certainly, some notes can be found on this theme in his book published in 1926 La représentation du monde chez l’enfant, translated into English under the title The Child’s Conception of the World (1929). However, the scope of that book does not focus primarily on the child’s representation of the concept of God, but rather on the child’s explanations of the origin of various elements belonging to nature: wind, sun, clouds, etc. In this context, the God figure can appear, but Piaget is above all interested in physical causality and the development of causal explanations in children. He observes, in the youngest children, an orientation of mind related to finalism. He identifies this attitude as precausal: the lake, the mountains, the sun, the moon, the wind, the clouds are there for something. If there are mountains, they exist for the purpose of going for walks; if the sun exists, it is there in order to illuminate. Initially, children are less interested in the questions of origin than in the questions of purpose, so if they are pushed to give explanations in terms of origin, they can as well attribute the origin of the elements of nature to God as to people who would have manufactured them.

Since some children attribute the origin of the world to God, Piaget wonders what role religious education plays in the emergence of such representations. In this context, he refers to the ideas set out by Pierre Bovet in Le sentiment religieux et la psychologie de l’enfant (1925). In his book, Bovet speaks of the spontaneous deification of parents by the child. The little child is inclined, spontaneously, to ascribe to his or her parents all of the attributes that theologies ascribe to divinities. In the process of growing up, the child discovers that his or her parents do not possess unlimited powers and removes the ascription of powers such as omniscience or omnipotence from his or her parents, and transfers them to God. In other words, the attribution of powers such as omniscience or omnipotence does not result initially from religious education, but rather it develops as a magnification of parental abilities by small children. This phenomenon, depending on the type of religious education received, may also extend to other figures. In these observations, Piaget speaks much more of the deification of parental figures than of the anthropomorphization of the divine figure.

Piaget never describes representations of God in children using the opposition between “concrete” and “abstract”. On the one hand, in 1926 Piaget has not yet used opposition in his work; on the other hand, for Piaget, it would not make sense to say that a representation of God is concrete or abstract. So, from where does misunderstanding originate? It comes from developmental psychologists who have applied the Piagetian theory of stages to religious development.

In the 1930s, Piaget developed a theory of operative development. It distinguishes a preoperative stage between about 2 and 6 years, a stage of concrete operations until around 12 years, and a stage of the formal operations from 12 years on. Studying representations of God in children, various scholars (e.g., Harms 1944; Goldman, 1964; Fowler, 1981; Oser et al., 1991) describe the development of these representations according to the Piagetian stages. Noting, among other things, a decrease in anthropomorphic traits with age, they conclude that representations without anthropomorphic features are abstract when compared to those exhibiting traits that can be considered more concrete. One could easily conclude that this evolution is in conformity with the description of the development according to the Piagetian stages.

However, there is a complete misunderstanding of what Piaget calls abstraction. In his cognitive-developmental theory, he does not speak of the opposition between concrete and abstract, but between concrete and formal. A child reasons at a concrete level when he or she mentally manipulates concrete objects (stones, people, etc.) in order to accomplish, for example, a comparison of quantities. He or she reasons at a formal level when he or she reasons in a hypothetico-deductive way and mentally manipulates formal symbols such as numbers or variables (Piaget & Inhelder, 1969). When it comes to abstraction, it already concerns the extraction of properties. For Piaget, the mental representation is an extension of the action. Already the child of less than 2 years is able to act in thought on the world, to have a mental representation of the world. In this sense, the mental representation is already an abstraction compared to the simple motor action. That is why, from a Piagetian point of view, omnipotence or omniscience are not, as Barrett claims (2001, p. 182), more abstract properties than having a limited power or a limited knowledge. Indeed, they are just properties attributed to objects, as any other properties that can be attributed to objects. That being said, let’s try to build a model that incorporates what we know about the development of the representation of gods from childhood to adulthood.

A Cognitive Perspective

Representations of gods or supernatural agents are never completely independent from the representations of human beings. Ana Maria Rizzuto emphasized this in her book The Birth of the Living God (1979). That is what Barrett calls “anthropomorphism in adult God concepts” (2001, pp. 178–181). To demonstrate this, Barrett relies on data collected with adults in various experimental situations (Barrett & Keil, 1996). In these situations, adults were told stories concerning gods and involving suprahuman properties (such as having no attentional or perceptual limitations). For example, one narrative suggested that God performs many tasks simultaneouly in different parts of the world. Comprehension and recall of stories was tested under conditions that induced cognitive pressure: the subjects did not have a lot of time to complete the task. Results show that, under cognitive pressure, adults tend to attribute

to God properties such as having a limited focus of attention, having fallible perceptual systems, not knowing everything, and having single location in space and time. In contrast, when these same participants were asked to reflect slowly and care fully on what properties they believed God has, they reverted back to the theologically correct, abstract properties (…) God is all-knowing, has infallible perception, has no single physical location, has unlimited attention, and so forth. (Barrett, 2001, p. 179)

Boyer (1994) inspires Barrett’s explanation: “Religious concepts only differ cognitively from ordinary concepts by a few minor violations of intuitive assumptions” (Barrett, 2001, p. 180). When the processing of a narrative demands quick interpretation, “many of the non-intuitive elements are likely to be ignored for the sake of processing efficiency” (Barrett, 2001, p. 181).

This explanation is based on the assumption that attributing omniscience or unlimited attention to an intentional agent is less intuitive than attributing anthropomorphic properties (such as having limited knowledge or a limited attention focus) to the agent. Nonetheless, the explanation is not convincing. As emphasized by Kaufmann and Clément (2007), individuals come to share cultural analogies due to their collective reality, and based on one’s anticipation about how others would perceive them and understand their social relevance. That is to say, one may not rely on an “actual” reality of things to depict God but instead attempt to communicate ideas about the divine that are shared in one’s social environment. From this perspective, it is in fact rather intuitive to attribute characteristics to God (or religious entities) that seem to be at odds with their general understanding of physics or biology—using the so-called ontological violations. While this is a general argument against the counterintuitiveness thesis, we will develop this issue further when dealing with developmental aspects of representations of God. We leave this to suffice for now, and turn to another consideration highlighted by Barrett. Among the characteristics associated with the concept of God, there is the characteristic of being an intentional agent, and the prototype of the intentional agent is the human being. According to the prototype theory (Rosch, 1973, 1978), the prototype is the most central member of a category, functioning as its cognitive point of reference. It presents itself as the best example of the category, the one we think of first when the category is mentioned. For example, the robin or sparrow will be more prototypical of the bird category than the ostrich or the penguin. Relative to a given category, a prototype maximizes information with the least cognitive effort. This is shown, for example, by the fact that the time required to handle issues involving a prototypical member (e.g., is a robin a bird?) will be shorter than for non-prototypical members of the same category (i.e., bird).

In our case, the category is intentional agency. When we say “god”, especially in stories like those told in the experiment situations described by Barrett and Keil (1996), it is clear that it refers to an entity, an agent endowed with intentionality. For human beings, it appears that a human agent is “the prototypical intentional agent” (Barrett, 2001, p. 180). That is why, when we have to deal with a story depicting an intentional agent without having time for reflection, we will tend to anthropomorphize it. Piaget would speak of assimilating a new situation to already constructed schemes; in this case, the egocentrism pushes us to project onto others what we have learned about ourselves. An example is the tendency, for example, to anthropomorphize the reactions of an animal. From an attachment point of view, one could argue that the ability to mentalize adds to meaningful forms of assimilation. Only securely attached persons can integrate internal and external worlds in such a way that they can ascribe intentions to others and use symbols that refer to otherness in a way that is personally meaningful.

This being said, anthropomorphic features in adult representations of gods are not, in themselves, a sign of a low cognitive level. If the prototypical intentional agent is the human being, it is perfectly understandable that people, including religious artists like Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel, use human shapes for representing the gods. We just have to be aware that making use of a prototype for referring to some features of an entity does indicate an affinity between the prototype and the entity. We must recognize the potential for the metaphorical use of anthropomorphic traits in a representation of the divine. Its purpose of using anthropomorphic traits is to signify (in a composition that is not reduced to the simple representation of a human being) that the figure represented is, among other things, an intentional agent.

A Developmental Perspective

After considering the integration of anthropomorphic traits in the representation of God from a cognitive point of view, let us see what happens when we add the developmental perspective. In a very nice paper, Barrett and colleagues describe the result of an experiment conducted with very young children (Barrett et al., 2001). They used a false-belief task. Three- to seven-year-old Protestant children were shown a cracker box. They were asked what they believed to be inside the box. They answered “crackers” or “cookies”. Then, they were invited to open the box, and they discovered that it contained small rocks. After reclosing the box, they were asked what their mother would think is in the box. Three- and four-year-olds answered “rocks”, while almost all five- to seven-year-olds answered “crackers”. When the same question was asked about God, children of all ages solidly answered “rocks”.

These results show that very young children tend to attribute omniscience to their mother. It is only around 5–6 years that they differentially attribute this property to the mother and to God. Curiously, Barrett (2001) considers that omniscience is an abstract concept. The attribution of omniscience already at 3–4 years would be proof that the child is prepared from an early age to conceive of the divine. In this respect, Barrett and Richert (2003) speak of the preparedness-hypothesis. However, nothing requires the assertion of such bold assumptions. Why not just consider that omniscience is seen by children of 3–4 years as an anthropomorphic property belonging to the concept of the adult human being? This idea of normal human omniscience is sustained by Winnicott’s emphasis on the importance of omnipotence experiences in young children (Winnicott, 1971). Thus, it is not necessary to consider omniscience, which becomes a religious concept in the adult, counterintuitive, as Boyer (1994) proposes. Indeed, Boyer posits that religious concepts differ cognitively from ordinary concepts only by a few minor violations of intuitive assumptions. However, the experiment with the box of crackers shows that, for 3–4 year-olds, omniscience seems more intuitive than believing that adults have limited knowledge. Therefore, if we can agree with Barrett and Richert that “prescholers seem capable of reasoning about God as an immortal, infallible, super-powerful being” (2003, pp. 310–311), it does not mean that these children reason abstractly. Indeed, these authors seem to forget that at age 4, children attribute this same property of omniscience to their mother (and sometimes to themselves)!

We can conclude that at this age, the construction of the concept of human being is no better than that of god. Between ages 4 and 6, a more accurate understanding of the concept of god goes hand in hand with a more accurate understanding of the concept of human being. This better understanding is achieved by reciprocal differentiation corresponding to selectively attributing the property of omniscience to gods. This evolution can be described as moving towards a less anthropomorphic representation of the concept of god, or it can be described as moving towards a less deified representation of the concept of human being. Both descriptions serve equally well.

This is what Bovet had already observed in 1925, when he spoke of the deification of parents by young children and the loss, when they grow up, of the illusion that their parents are omniscient or omnipotent in order to attribute these properties solely to God, henceforth. To conclude this discussion of Barrett’s positions, we can agree with him that “the data cited to support the anthropomorphic-to-abstract shift through development may be understood better as a shift from poor to better general processing abilities (…)” (Barrett, 2001, p. 174). However, we cannot follow him when he identifies non-anthropomorphic properties with abstract ones and sees abstractness in the reasoning of young children.

On the heels of this discussion of the development of the concept of the god from childhood to adulthood, let us concentrate on what can be said, from a developmental point of view, of with regard to the occurrence of anthropomorphic traits in children drawings of god.

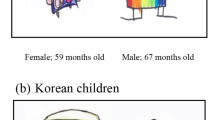

Many scholars have observed a decrease, between the ages of 6 and 16, in the proportion of god drawings depicting anthropomorphic figures, both in Western and Christian contexts (Hanisch, 1996; Kay & Ray, 2004; Ladd et al., 1998; Pitts, 1976; Tamm, 1996), and in non-Western and non-Christian contexts such as Japan (Brandt et al., 2009) and Buryatia (Dandarova, 2013). Dessart and Brandt (Chap. 4, this volume), by using a strict binary categorization (presence or absence of anthropomorphic features in the representation of god figure) were able to replicate this finding on a sample of 532 Swiss participants (5–17 years old). In this same study, they note that of the 493 drawings with a single-God figure, drawings devoid of any anthropomorphic features make up only 5.5%. What can we conclude from this observation?

Probably this is a clue that with age, children become more aware that a drawing that looks too much like a human being could be confusing. It might look too much like, well, a human. A kind of otherness is required. Guthrie (1993) has observed that in many religions human and non-human characteristics seem to co-occur in divine representations. He has argued that rather than mere anthropomorphism in such figures we found both sameness to and otherness from the human being. In addition, for an artist (e.g., a child) to wish to convey the idea that God is somewhat like a human but not only human requires that they have developed what Freeman and Sanger (1995) have called a mentalistic theory of pictures in order to produce an effect on the beholder. This theory supposes some basic understanding about the fact that pictures are made of intentions.

A person looking at a given drawing may not understand that it represents a supernatural being. For example, Lis, a Swiss girl (12 years, 8 months old), gives the following description of her drawing (ch16_fr_f_rec_12_08_lis) (Fig. 2.1).

In my opinion, God has a physical appearance of a classical shepherd. But you will never see him like that. Because when you have a problem to solve, or that someone tells you they have seen God, in reality, he sends us his spirit. God is everywhere, and watches over each one of us.

This awareness of the ambiguous character of an iconographic representation of god can also be expressed in the case of non-anthropomorphic representations. For example, Atx, a Japanese girl (13 years, 10 months old), describes her drawing (jp04_fa_f_pkx_13_10_atx) (Fig. 2.2) as a “kind of sun or moon” in the “form of a globe” and adds: “It is not the form of an object, but it is God (Kami) that I imagine and that I drew like this”.

However, the binary opposition (presence or absence) of any anthropomorphic traits is much too crude to account for the treatment of anthropomorphism in children’s drawings of god. It might lead one to believe, for example, in the case of the Swiss sample analysed by Dessart and Brandt (Chap. 4, this volume), that almost 95% of all children between 6 and 16 years of age draw God as a human being. It is not the same thing, however, if a child draws eyes and a mouth in a cloud, a headless human shape, or a figure, as if he or she had been invited to answer the Draw-A-Man test (Goodenough, 1926). This is why Dessart and Brandt (Chap. 4 this volume) carried out a detailed analysis of the so-called “anthropomorphic” representations. They distinguished human-based (n = 390) from non-human based (e.g., eyes and mouth in a cloud) representations (n = 9). They showed that children make use of a wide variety of processes to incorporate anthropomorphic traits into god drawings that also contained non-anthropomorphic features. In doing so, the children use different strategies to insert clues into their drawings that signal divergence from a representation of a mere human being. Applied to human-based representations, Dessart (Chap. 3, this volume) calls these processes “de-anthropomorphization”.

Some strategies operate directly on the figure of God. For example, the child adds (e.g., wings) or associates (e.g., aura or halo) non-anthropomorphic traits to a human-based figure. In another strategy, children add or remove human features. They may add extra human features to the basic ones (e.g., adding a pair of arms or eyes), or they may remove some features that would normally be present (e.g., head or face). The child can also de-anthropomorphize the drawing by altering the background (the context in which the figure is set). For example, the anthropomorphic God figure may be drawn in a context uncommon for a human being (e.g., on a cloud, in the sky), or placed in relation to other objects (e.g., abnormally larger than other human figures) to indicate its superhuman nature.

Among the 390 human-based representations of the Swiss sample analysed by Dessart and Brandt (Chap. 4, this volume), nearly 70% are characterized by the use of at least one of these de-anthropomorphization strategies. Interestingly, only age was a statistically significant predictor (p < .001) of the distribution of these strategies in the sample. De-anthropomorphization increases from age seven to age nine, and then again from age 12 to age 15.

Children, by a more or less metaphorical use of anthropomorphic traits, clearly signify that god is an intentional agent. At the same time, they make use of the above described strategies, combining anthropomorphic traits with the presence or absence of other traits that are incompatible with the standard representation of a human, in order to ensure that there will be no possible confusion with a mere human being. The increase of de-anthropomorphization strategies with age indicates that as children age, they become aware that a person viewing their drawing might experience such confusion. At the same time, the large presence of anthropomorphic traits in the drawings shows that these traits remain a valid (graphic) means for expressing that god is an intentional agent.

In concluding this part on anthropomorphism used in drawing god, it is important to remember that the presence of anthropomorphic traits is not in itself an indicator of a low level of development, as suggested by previous works. In other words, the absence of anthropomorphic traits is not a criterion, in itself, to conclude that the representation is the expression of a greater cognitive maturity. It is not so much the presence or absence of anthropomorphic features in the drawing that matters, but rather the way these features are treated.

Gender in Children’s Drawings of Gods

Producing a representation of a figure that incorporate anthropomorphic features confronts to the question of gender: are these features specifically associated with a masculine or a feminine representation, or are they not particularly connected to either one? How is this question of gender managed by children when they are drawing gods?

Previous research has shown a same-gender preference among girls and boys when they are simply asked to draw a person (Arteche et al., 2010; Chen & Kantner, 1996; Harris, 1963; Willsdon, 1977). Concerning representations of God, Vergote and Tamayo (1980) published a series that convincingly shows that these representations encompass typical traits of both a mother figure (e.g., nurturing, supportive) and a father figure (e.g., punishing, powerful). These studies used techniques other than the drawing task, and presented convergent results in different countries of Europe, in North America and in India. However, when studied by the means of the drawing task, the impact of the cultural environment cannot be ignored. The majority of previous research has been conducted in Western environments characterised by Christianity and monotheistic traditions (Bucher, 1992; Daniel, 1997; Hanisch, 1996; Kay & Ray, 2004; Klein, 2000; Ladd et al., 1998). In this context, the gender of God is clearly presented as masculine. Unsurprisingly, material collected in these environments reflected masculine gender traits, and the few figures displaying feminine traits were produced only by girls. In a Japanese context, results were quite different. In a cultural context where “kami” (the term used in this context as the best equivalent for “god”) is not so strongly associated with masculine features, almost a third of the figures were feminine (produced by boys and girls), and nearly half of the girls felt free to draw a feminine figure (Brandt et al., 2009). These results are also in line with studies showing that girls, more often than boys, are ready to express cross-gender behaviours or preferences (Bussey & Bandura, 1992; Martin, 1993). Similarly, Dandarova (2013) working in a Buryat (Siberia, Russia) context where Buddhist, Shamanistic, Christian, and atheist influences coexist, observed that girls were more inclined to draw feminine gods (15.4%) than boys (0.9%). These results show that cultural factors interact with the gender of the child when rendering the representation of gods. In an environment with a strong masculine representation of God, the proportion of feminine drawings of gods do not go beyond 7% (Hanisch, 1996; Ladd et al., 1998). We can conclude from these observations that when a specific gender is attributed to god at the cultural level, this attribution exerts such a strong pressure that it no longer leaves room for the choice of gender attribution at the individual level.

Dessart et al.’s (Chap. 5, this volume) analysis of gender-typing using a Swiss sample of drawings brings arguments for rejecting this too hasty conclusion. In a preliminary analysis of a previous state of the Swiss sample (n = 329), a binary categorization of god representations yielded the result of only 0.9% of female figures in total, 0.6% by boys, 1.2% by girls. In fact, scoring anthropomorphic drawings following a binary masculine-feminine categorization leads to an overestimation of the proportion of masculine representations. In order to demonstrate this, we must first draw away from a binary categorization of gender, and we must not aggregate the non-feminine into the masculine category. This is what Ladd et al. (1998) have already proposed by introducing neuter option (neither masculine nor feminine) in their categorization. As a result, they identified 57.7% of figures as masculine, 37.5% of figures as neuter, and 6.8% of figures as feminine.

Extending this approach, Dessart (2019) proposed a dimensional method to gender-typing where he asked adult raters to simultaneously assign a femininity score and a masculinity score to each drawing from his Swiss sample. Scores range from 0 to 10. The final scoring for a drawing was obtained by using the average-split method proposed by Riegel and Kaupp (2005). Drawings scoring equal to or above average on the femininity dimension and below average on the masculinity dimension were moved into the feminine category. The same logic was applied to the masculine category. Drawings scoring below average on both dimensions were labelled undifferentiated. The advantage of this scoring method is that it made possible to identify a fourth category, constituted by the drawings that received scores above average on both dimensions. This category was labelled “androgynous”. Arguably, Ladd et al.’s (1998) neuter gender category covered both of Dessart’s undifferentiated and androgynous figures. This scoring method allows researchers to acknowledge feminine features in drawings where they are mixed with masculine ones. This method shows that, in terms of gender attribution to god figures, gender is not strictly a binary classification. Using this dimensional approach, Dessart (2019) made the following observations. Boys drew 50% of figures as masculine, 24.2 of figures as feminine, 19% of figures as undifferentiated, and 6.8% of figures as androgynous. Girls drew and 39% of figures as masculine, 41% of figures as feminine, 9.5% of figures as undifferentiated, and 10.5% of figures as androgynous figures. These results show that the labelling of a representation as masculine or feminine strongly depends on the method used to score the drawings. They also show that a binary categorical approach has the effect of disguising female aspects under the overall label of the masculine. The use of a dimensional approach brings out these masked aspects and reveals that gender attribution to representations of divine figures is more complex than a simple masculine-feminine dichotomy.

Then, if we add the developmental dimension, we find that, with age, the attribution of the masculine gender to god becomes more and more dominant, in girls as in boys. This certainly demonstrates the influence of the cultural stereotype on children, which is increases as they grow older. This effect is more marked in boys, presumably reflecting the effect of same-gender preference. As gender typing an androcentric cultural figure is more complex for girls than for boys, it is understandable that undifferentiated and androgynous categories have larger proportions in girls than in boys. This suggests that girls are expected to be more flexible than boys relative to gender attribution, and that the obligation to consider cultural references becomes more pronounced for children, as they grow older.

Gender-typing god may thus reflect the deeply intricate combination of several factors. As we have just seen, same-gender preference appears to be at work. Dessart (2019) has suggested that the broad cultural androcentrism generally associated with god in the West might explain two additional partly distinct factors. One of them pertains to an exposure effect of over-represented masculine figures within a religious tradition (Whitehead, 2012). A second one deals with hegemonic masculinity (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005), characteristic of a more general and more pervasive cultural androcentrism which is not limited to the religious domain.

This brings us to the role of culture, which is the theme of the next section. Keep in mind, however, that the main results from this section on gender demonstrate that even within the Western world dominated by male representations of God, the question of the gender of god is contemplated by children and is reflected in the strategies that they use to differentiate between God and a mere human being. This can result in an undifferentiated or androgynous figure—the latter of which may reflect the use of ambivalence.

Influence of Cultural Representations in Children’s Drawings of Gods

When we began this chapter with the topic of anthropomorphism in the representations of god from a cognitive and developmental perspective, we proceeded as if the child had to invent everything. However, as we have seen with the dimension of gender, the cultural environment in which the child is immersed conveys pictorial representations of supernatural agents, and these representations have an impact on what children draw. These representations are, of course, provided by the religious traditions, through artefacts and emblematic images (paintings, sculptures, educational material, etc.); but that is not all. They can also be found in iconographic productions that are not directly related to religious institutions: in illustrated books, cartoons, comics, films, advertisements, etc., that feature fairy tales, biblical, religious, mythological, or science fiction stories (Brandt et al., 2019). As Harris (2015) demonstrates, children build their representations of religious concepts in the same way that they build scientific concepts: through testimonies produced by adults. This information suggests that the same applies to the concept of god.

Testimonies about iconographic representations of the divine are present in the cultural environment. When children try to represent a supernatural agent graphically, they are not the first in the history of humanity to do so. Solutions used in the past and still present in the cultural environment can be sources of inspiration for the task.

We can compare solutions proposed by artists in the past with representations of god drawn by children. Some children choose one of the representations available in their cultural context and try to reproduce it. In doing so, they do not necessarily produce a representation of the god they, themselves, visualize. In the drawing protocol of the Children’s Drawings of Gods project,Footnote 2 children were also not explicitly asked to draw the god representation to whom they relate personally. Thus, children from Buryatia drew gods of the Ancient Greece, namely Zeus, Poseidon, Ares, and Athena (Brandt et al., 2019; Dandarova, 2013). These children had received instruction on this topic in history classes a few weeks prior to the study, and they took the iconographic material that had been presented to them as a model for their god representations. Similarly, children who self-identify as not believing in god (saying that there is no god) have produced drawings of god that, in some cases, appears to be a reproduction of a religious representation such as a seated Buddha or Jesus on the cross. In fact, the task to draw god simply asks children to draw god, it does not say, “draw your god”. Some children even emphasize the fact that they drew god of others. Therefore, a possible answer to the task may be limited to reproducing one god representation from among those available in the cultural context. Other children make more use of personal creativity and produce a more individual, sometimes unique image of god (Dandarova-Robert et al., in press). Any child can demonstrate a creative independent mind. As Reich (2009) notes from his observations on Nina: “to some considerable extent [she] constructs her religious world view from her own observations, analogies, imaginations, and reflections.” (p. 287). The decisions that introduce variations into the drawings can be made at different levels: the choice of figures and motifs, the composition, the colour palette, the emotional valence. Additionally, whether the children experienced the location of their participation (a school, a church, a mental hospital an asylum) as secure or insecure also influenced their choices. All of these choices connect to features associated with the concept of god.

However, the variability observed across the different cultural contexts shows the influence of these contexts: the probability that a child produces a given representation in a specific context is influenced by the greater or lesser diversity of representations available in that context, and by the frequency with which the available representations occur (i.e., which is most commonly found). In Iran, for example, anthropomorphic representations of god take often the form of the Prophet or of Imam Hossein, with a shining disk instead of a head. Many children respond to the task of drawing god by representing the blessings of God: a landscape representing the creation, their family, etc. (Khodayarifard et al.; Astaneh, Chaps. 12 and 15, this volume). Iran is also the country where the proportion of children who turn in blank sheets of paper is highest, even if, overall, this proportion remains very low (5%, in Iran, 177 out of 3000 drawings, compared to 2% in Switzerland, 7 out of 532 drawings). Children who respond in this way often state “it is not possible to draw God” or “it is forbidden to draw God”. Iranian children find various other strategies to answer the task of drawing god. To draw the Prophet, an imam, the blessings of God, or to give back a blank sheet, are different strategies expressing the way in which the Iranian children deal with the theological implications of this representational issue (the permission or prohibition to produce images of God and, more broadly, sentient beings) as it is discussed in the (Shi’ite) Muslim context (Astaneh, Chap. 15 this volume). Swiss children appear to consider similar theological imperatives. Aside from the theological aspect, however, children have difficulties creating a graphic representation of something, in this case god, that they can hardly comprehend or imagine. The strategies, such as those described above, that children use to overcome these difficulties can also be observed in other countries where drawings of gods have been collected.

Comparisons between countries lead to the observation of the major impact of the cultural environment on the types of drawings produced by children. Even inside the same country, different religious or cultural backgrounds have various impacts on the diversity of drawings that can be observed when subsamples are compared. That is the case inside Iran, in the six cities where drawings were collected (Khodayarifard et al. Chap. 12, this volume). This is also the case in Russia, when the drawings collected in Buryatia are compared with those collected in Saint Petersburg. Buryat children frequently drew Buddha and other personages or themes in relation to this religious tradition (Dandarova, 2013) while Russian-Slavic children, especially participants from the Orthodox parishes (Saint Petersburg) drew pictures inspired by Christianity (Dandarova-Robert et al., in press). Generally speaking, the degree of homogeneity of the cultural background has an impact on the diversity of drawings. Pluralistic cultural contexts such as Switzerland or Russia provide a greater variety in the representations of gods than non-pluralistic cultural contexts, as we see from the sample collected in Iran. For that reason, the probability of finding drawings that combine features drawn from more than one religious tradition is greater in the pluralistic contexts.

To summarize this section, it is important to keep in mind that, when asked to “draw god”, children can simply respond the task by reproducing models available in their cultural and religious environment. However, by doing so, they reveal that they have identified, in this environment, the cultural codes associated with the representations of the divine. It means that, cognitively speaking, the child asked to draw god is considering not only a concept, but also cultural representations (religious images, representations of characters in films, books, artefacts, etc.) that are available in his or her environment. That is to say, the study of children’s drawings of gods informs us not only of their understanding of the concept of god, but also of their ability to interpret a symbolic and iconographic language. It informs us of their ability to deal with universal features associated with the concept of god as well as with features specific to each cultural background. The characteristics of being an intentional agent who is omniscient and has superhuman powers seems to be common to all gods, but other features are not universal. Gender attributed to the god figure is one feature that makes possible to differentiate some cultural representations of gods from others. Age attributed to the god figure could be another differentiating feature that has not yet been thoroughly explored. Another consideration is the possibility of having a personal relationship with a protective god. Indeed, some religious traditions depict god (or gods) as figures who protect those who have a relationship with them. Would attachment theory explain some aspects of children’s drawings of gods? This is the theme of next section.

Children’s Drawings of Gods from the Point of View of Attachment Theory

We have mentioned before that when children draw god, that does not necessarily mean that they, themselves, have experienced a personal relationship to a god. Some of them, however, have built such a relationship, and when this is the case, it can make a difference in the way that they draw god. Also, when god objects are commonly known as relational objects in a specific cultural context, one could expect relational aspects in the drawings. Attachment theory can provide a helpful perspective from which to study these relational components.

There are several studies of children’s God representations in relation to attachment (Cassibba et al., 2013; De Roos et al., 2001, 2004; Granqvist et al., 2007). However, none of these studies used drawings as a method to investigate aspects of children’s representation of the divine (God). Moreover, existing studies that focused on children’s drawing of god(s) did not include attachment factors in the analyses. Further exploration in this research area could help us to better understand how a child’s relationship to god influences the manner in which the child draws god. Hence, the study conducted by Muthert and Schaap-Jonker in the Netherlands (Chap. 11, this volume) aims to contribute to the study of attachment and religion and of children’s religiousness and spirituality, and also to the study of children’s drawings of God. In their study, these scholars have not directly assessed the religious attachment of a child, but have assessed his or her attachment to parents, which can be described as secure or insecure. The attachment style results first from experiences with significant primary caregivers; it is later transferred to new relationships. This would potentially include relationships with spiritual figures. However, as previously noted, building a relationship with a spiritual figure is not necessary; thus, not every child can be described as having built an attachment bond to god.

In their study, Muthert and Schaap-Jonker did not compare children with and without an attachment relationship to god. They favoured another approach. They assessed the attachment style and using qualitative methods, sought to determine if the attachment style influenced child’s openness to religious symbols. In this way, Muthert and Schaap-Jonker combined emotional and environmental factors in their design. As a result of their comparison of 12 securely and 12 insecurely attached children, they learned that securely attached children used more god representation related symbols. They interpret this result to be a consequence of a greater openness towards the (religious) environment, because securely attached children would be more willing to trust the social environment. Insecurely attached children would be more fearful and avoidant, and consequently less open to the various contents available in their environment. This can be interpreted as one aspect (among others) of the emotional dimension present in the drawing of god. When we rate the infill of the paper we do see that the securely attached group uses more infill in comparison with the insecurely attached sub group. This outcome concretely supports our finding that the securely attached group uses more symbols.

Additionally Muthert and Schaap-Jonker found that the insecure group drew fewer anthropomorphic images. When it comes to the localization of God (extra-terrestrial, in heaven, between heaven and earth, on earth or no references to localization), the secure group used more localizations than the insecure group. When children from the insecure group did localize God in heaven, the insecure group drew heaven on the lower part of the paper while the secure group used the upper part.

In sum, Muthert and Schaap-Jonker’s qualitative exploration suggests that attachment styles indeed could be reflected in the drawings of God. They were only able to include a small amount of drawings, which is a limitation, but the analysis of these particular drawings finally suggested that the assumptions behind the theory of attachment need to be adjusted when dealing with more diverse cultural contexts. An important question that has arisen in light of these drawings and their accompanying narratives involves the values behind the so-called insecure and secure relational patterns in the major attachment models. Operationalizing along the dimensions of anxiety and avoidance highlights the individual autonomy in a way that does not seem to be universally applicable.

Emotionality in Children’s Drawings of Gods

An attachment approach to god representations implies a focus on the emotional and relational aspects of god representations. A child’s early experiences in close relationships (usually with the parents or other attachment figures) are generalized and represented in internal working models of self and others, which function as a template for future interactions on an implicit level of awareness. Hence, these representational models guide and integrate children’s embodied, emotional experiences in relationship with the divine, and affect their religious or spiritual functioning at an emotional and relational (largely nonverbal) level (Granqvist & Kirkpatrick, 2016; Hall & Fujikawa, 2013). By implication, feelings of either closeness and trust, or anxiety and avoidance (or combinations of these feelings) resonate in children’s drawings of their god representations.

The attachment style is certainly influencing the emotional dimension of a drawing, but there are other ways to approach it. Whatever the attachment style, children show a growing ability, with age, to express emotions in drawings (Jolley et al., 2016). Another aspect of this perspective concerns the emotional valence of the representation: Does the drawing express positive (joy, happiness) or negative (sadness, fear, anger) emotions? The representation of the divine can also be connoted in various ways: If the god is represented as a judge, he may be drawn exhibiting a state of anger or the drawing will express coldness; a benevolent god will be drawn manifesting warm mercy or happy contentment. These emotional attributions may result from the manner in which a divine figure is culturally conceived and/or from the personal experience of the author of the drawing. In fact, to remain at a distance from a divine figure and to fear it, or on the contrary, to seek its protection may result from a culturally transmitted teaching, but it also may result independently from the individual relationship that the author of the drawing experiences with this divine figure.

Although research on the emotional dimension of the representation of god is not lacking, there is, unfortunately, almost nothing that has been done in the area that includes drawings of god (Dessart, 2019; Jolley & Dessart, Chap. 10, this volume). Jolley and Dessart are pioneers in this field.

Dessart (2019) have asked two female expert artists to score the intensity and valence of emotionality expressed in the same Swiss sample of drawings that Dessart and Brandt (Chap. 4, this volume) had analysed for anthropomorphism and gender. In contrast to the general scientific literature on children’s expressive drawings, no age-dependency for emotional intensity was observed. Dessart proposes two different explanations. The first one suggests that an increasing ability to express emotions in drawings would be counterbalanced by a decreasing intention to draw expressively when asked to draw god. This would be consistent with the tendency to draw god in a less anthropomorphic manner in the sense that emotions are anthropomorphic features. A second explanation is that the task of drawing god, when approached with an emotional lens, may reflect one’s personal commitment in relation to god. In that sense, the result would appear to depend mainly on socio-cultural factors that are fairly fixed, rather than occurring as the result of changes in life course. For that reason, the scores of emotional intensity remained average at each age. Being a girl or receiving religious schooling increased the likelihood of producing an emotionally intense drawing of god. Concerning gender, this is consistent with previous research that shows female individuals to possess better expressive drawing abilities (Brechet & Jolley, 2014). This is also in line with previous studies that suggest female individuals are generally more religious (Francis 1997) or that girls (aged 4–10 years) perceive god to be closer than boys do. Concerning schooling, this finding suggests that emotional intensity is associated with religious socialisation. One possibility might be that the more familiar with the god figure the child is, the more she/he can engage in an emotional relationship with this figure. However, it could also happen that where socialisation is recognized on an explicit level, the personal affective relationship could still be coloured by an insecure attachment style (Hall & Fujikawa, 2013). Another, non-exclusive, possibility would suggest that the more children are exposed to emotionally intense depictions about a given category (i.e., the divine)—which is likely the case in the religious schooling contexts concerned—the more prone they are to reproduce strong emotionality, as per the exposure effect. This is in line with results regarding emotional valence.

The results concerning the emotional valence can be interpreted in the same way. The more familiar children are with the concept of god, the more they attribute a positive emotional valence to it. This supposes that, in the Swiss context where these results were obtained, the concept of God is rather positively connoted. Greater familiarization leads to a friendlier relationship, because what is unknown can lead to mistrust. The gender effect, a higher positive emotional valence for girls than for boys, may be only the consequence of a greater emotional commitment already highlighted when measuring emotional intensity.

Impact of Religious Education and Religious Socialization on Children’s Drawings of Gods

As we have just seen, religious education has an effect on the representation of god in terms of greater familiarity with this concept, and therefore a greater tendency to conceive god in a positive way. Hanisch (1996) highlighted another aspect of the impact of religious education: a greater decrease of anthropomorphism in God representations for children with religious education compared to those without such education.

Hanisch collected more than a thousand drawings of God among children aged 6–16, in Heidenheim, West Germany, and more than a thousand drawings in Leipzig, in former East Germany, just after the fall of the wall in 1989. In Heidenheim, the school program for children between 6 and 16 included 1 h of weekly religious education. In the communist regime of former East Germany, there was no religious education in the school curriculum at Leipzig. In his study, Hanisch observed a decrease of anthropomorphism in the drawings with age. This decrease was more pronounced and began earlier in Heidenheim. It was only at the age of 14 that the proportion of anthropomorphic representations fell to less than 80% in Leipzig, when it was already below this threshold at the age of 10 in Heidenheim. In Heidenheim, the percentages ranged from 70% at age 10 to 21% at age 16, while in Leipzig, 79% of drawings were still anthropomorphic at age 14 and the percentage did not fall below 76% at age of 16. These results show that religious education has an influence on anthropomorphism in children drawings of God. This can be explained by the fact that thinking about a concept makes it possible to move away from spontaneous representations. That is to say, there is a tendency to anthropomorphize the representation of any figure understood as an intentional agent. Brandt et al. (2009) obtained similar results in Japan: from the age of 12, the proportion of anthropomorphic drawings decreases among children attending Buddhist schools but not among those attending state schools.

Similarly, Dessart and Brandt (Chap. 4, this volume) have found an effect of schooling on the use of anthropomorphism, similar to that reported by Hanisch. However, the overall percentage of anthropomorphic figures in their Swiss sample was 87.6%. This closely corresponds to the percentage found by Hanisch in Leipzig (87.5%) and is far above the proportion found in Heidenheim (57.8%). Such a disparity might reflect even more clearly the important role played by religious education. It can be assumed that the group of children from Heidenheim received more frequent and sustained religious education compared to children from the Swiss sample. In the latter, only a minority of children from one particular geographical area (canton of Fribourg) were attending religious classes weekly. It is also noteworthy that Dessart and Brandt have processed non-figurative representations separately from non-anthropomorphic ones. Hanisch did not do this, and as a result, his data might have led him to overestimate the proportion of non-anthropomorphic figures in his study. In their study, Dessart and Brandt have constructed a rather elaborate visual representation of drawings from their Swiss sample in the form of a tree. The reader can see an early division between two main types of drawings: those that show a direct God representation and those that do not. The latter group includes representations such as a blank sheet (e.g., nothing has been drawn or the artist has left a few words explaining why she/he could not draw God), God’s manifestation (e.g., the Creation), invisible God (e.g., meta-graphic signs indicating that God lies in some place in the drawing composition where nothing has been actually drawn). It is therefore worthwhile that—contrary to Hanisch—drawings displaying God’s hand would be categorized in the former group made up of direct representations. There is a major difference between the authors’ approaches to coding. Hanisch focusses mainly on the symbolic status of representations even when they are somewhat anthropomorphic, as in the case of a hand coming into the composition through the sky, for example. Dessart and Brandt instead began by considering that all anthropomorphic God figures could potentially be deemed symbolic. This was confirmed through individual semi-structured interviews conducted by Dessart (unpublished) where some interviewees, who had previously taken part in the Swiss quantitative study, explained their use of anthropomorphism. They argued that they were aware that God “is not a human being” but found that it was often most convenient to depict God in that way. Their approach, therefore, relied on an early distinction between direct (or figurative) and not direct (or non-figurative) representations. Their categorical system is similar to Dandarova (2013) in that regard.

In Hanisch’s (1996) study, representations of a hand were categorized as symbolic—and non-anthropomorphic—and this type of drawing was very frequent in Western Germany (25% of all symbolic images).

Given that this type of drawing (by content) is found so frequently across Hanish’s Western sub-sample, it can be somewhat misleading to code a quarter of “symbolic” God figures accordingly and thus conclude that his sample from Western Germany, because of religious socialization or education, was more inclined than his sample from Eastern Germany to represent God through symbolic means.

Religious schooling also has an effect on emotional expression in children’s drawings of god and can be interpreted as a form of what Harris (2015) calls testimonies. Dessart (2019) in their analysis of emotional intensity and emotional valence, found religious schooling to be a consistent contributor: Children from the religious schooling group drew with more intensity and their drawings displayed a more positive valence overall.

Ambivalence: Attributing Contradictory Properties Simultaneously to Signify a Being Beyond Any Categorization

Before concluding this chapter, we would like to highlight one characteristic of the representation of god that winds through many of its dimensions: ambivalence. Vergote and Tamayo (1980) had already pointed out the incidence of ambivalence that they found in their studies comparing the representation of parental figures with that of God. They showed that the representation of God combines maternal and paternal traits. To postulate the ambivalence of god representations on the basis of this unique result could elicit the criticism that this characterization is merely the by-product of the method used to measure the paternal or maternal character of the figure of God. In fact, the combination of paternal and maternal traits also characterizes the representations of both the figure of the father and the figure of the mother. However, it is more marked for the figure of God. Thus, even if the method might reinforce the hybrid aspect of the representations studied, the comparison between the representations of the parental figures and the figure of God makes it possible to show that ambivalence characterizes the figure of God in particular.

We obtain the same conclusion from the dimensional study of God’s gender conducted by Dessart (2019). Drawing an androgynous figure is a strategy chosen by some children to differentiate the representation of God from a simple human being. In the Swiss sample where both feminine and masculine dimensions were scored on the same drawings, androgynous representations were produced by 6.8% of the boys and 10.5% of the girls. This percentage increases with age among girls, moving from 6.9% for the youngest girls to 16.4% for the older girls, while it decreases slightly for boys, moving from 9 to 5%.

Ambivalence, to some degree, can also be observed on the emotional level. Drawings judged “of equal balance” in that regard accounted for 10.47% of the drawings from the Swiss sample that received an emotional valence score. To enter the “of equal balance” category, drawings had to be equally negative and positive, with at least some emotional intensity. That is to say, they could not be emotionally bland. There does not seem to be a clear developmental pattern in this small portion of drawings, although most of them are found at the ages of 8, 12 and 13 years. Some differences can be identified, however, for gender and schooling: boys had drawn 76%, of these drawings and 68% had been drawn during regular (non-religious) schooling. While this category includes various types of drawings, two main types seemed to emerge. First, some drawings simply failed to lend themselves more strictly to one of two valence directions (positive or negative). Second, other drawings appeared to refer intentionally to opposites that are emotionally connoted, such as depictions of heaven and hell.

The study of humanness and non-humanness (Dessart; Dessart & Brandt, Chaps. 3 and 4, this volume) has also shown how children made use of different semantic categories, combining some of their subcategories to convey ideas about god. In a strict sense, this may not reflect ambivalence. Nonetheless, if we consider humanness and non-humanness as opposites, then one can see how children may play on these irreconcilable subcategories to depict god. This may be done either by retaining fidelity with existing forms provided by their cultural background or by taking a relative degree of freedom. Instances of such endeavours can be found in the figure of god itself with features that are added (e.g., wings), replaced (e.g., light in place of the head), associated with it (e.g., nimbus), or in the background of a composition (e.g., celestial background). More than ambivalence in and of itself, this could reflect a general underlying tendency to bring together binaries when god representations are called. In the case of humanness and non-humanness, there was a trend, with increased age, towards a more frequent semantic combination, which did not depend on either schooling or gender.

Attributing opposite properties to the representation of gods seems to be a way of indicating that to be divine means to be beyond categorization. It is a way of showing that god cannot be captured by dichotomous categories. This is what people have tried to express through language in the forging this concept. If a figure has limited powers or is subject to any limitation, then the figure does not correspond to what is characteristic of divine figures. A god is called “god” because he or she crosses borders and can be simultaneously on both sides. That is why the concept of god cannot be manipulated in the same way as the concepts of the human being or the earthly living being. It is also remarkable that the ambivalence attributed to the concept of god can be expressed at different conceptual levels (gender, emotional valence, semantic and attachment categories, etc.). For instance, as children combined both secure and insecure attachment aspects in their drawings of God, they demonstrate openness to ambivalence and more complex configurations of God representations. This can be interpreted as a sign of healthy development, reflecting the acquirement of psychological capacities such as the ability to tolerate ambiguity and frustration.

Synthesis

In the introduction to this chapter, we asked the question: How is it possible to draw something or somebody that I have never seen? Faced with the task of drawing god, children of school ages provide us with some answers. Even if they have never seen gods, most of them have seen representations of divine beings or of supernatural agents, either in religious settings or in the media. They can fulfil the task in reproducing one of these images to the extent of their abilities.

They can also, without thinking too much, rely on the fact that the concept of god includes intentional agency, and can thus draw god by drawing the prototype of the intentional agent—a human being. The older the child, the more likely that these strategies will be the object of critical cognitive treatment. The child, as she/he grows up, will tend to question the meaning of the concept of god and the adequacy of the iconographic material to which she/he has access, rather than sticking to a spontaneous answer or simply reproducing the iconographic models available in the cultural environment. At least, this is true for specific dimensions. In these studies, the most striking case is found in de-anthropomorphization: we observe that in each successive age bracket (the older the child), more children would draw away from typical human representations. For other aspects, such as gender-typing, emotionality (valence), and spatiality (position), increasing age seems progressively to bring children to conform to religious representations accessible in their cultural environment.

This tendency to apply reflective activity to pictorial representations of god may also be favoured by solicitations from one’s social environment. In this sense, religious education appeared to play a role in broadening the child’s own repertoire of possible representations of the divine. This could be observed in the preference for non-anthropomorphic representations (vs anthropomorphic) among children receiving religious education. Conversely, when emotional expression is considered, representations of god tend to conform to traditional religious images if children receive religious education. This bears similarity to observations made about the influence of age. Such reflections depend, as noted above, on the specific dimension at stake, emphasising the importance of acknowledging the composite nature of god representations.

We will now break down such critical, reflective, activity into four specific ways that this can be expressed in children’s drawings of god. First, as children grow older, they become more and more sensitive to the ambiguity of representing the divine without giving any clue in the drawing to indicate that it is not a mere representation of a human being. Certainly, such a representation can take a metaphorical value. In the same way that Michelangelo consciously painted a very human-looking God on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, children are generally aware that their drawings, even if very similar to a human being, are not realistic portraits of God. To emphasize this, they will use de-anthropomorphization strategies. Michelangelo chose to represent a floating God in a celestial environment. This is an example of a de-anthropomorphization strategy: floating in the air is not a property of a human being. Dessart and Brandt (Chap. 4, this volume) describe a whole series of de-anthropomorphization strategies used by children. Even though their god drawings contain anthropomorphic traits that pictorially signify that they conceptualize god as an intentional agent, the representation of the divine figure and the choice of the context in which it is represented serve to differentiate the representation of god from that of a mere human being. Now, one may yet argue that such strategies follow some sort of implicit rules found in traditional religious images. For example, combining ontological categories can also be found in depictions of angels, with the insertion of wings or of a nimbus. Nevertheless, only age influences the use of such strategies, not gender or religious education. Therefore, even if the representations resemble traditional religious images, they testify to a level of complexity that requires cognitive development.

Second, along with the use of de-anthropomorphization strategies, children can use an additional form of criticism in relation to spontaneous representations of god: the criticism based on representations considered valid (legitimate) within the framework of a given religious tradition. Conformity or non-conformity with these models—which themselves are often also the result of de-anthropomorphization strategies—can be used to question representations that may seem too human. However, this criticism can also simply refer to the prohibition of leaving certain iconographic frameworks.

Hence, the third direction can appear; the representations can be considered as cultural or religious models. There are traces of this in the ambivalence of the gender of god, specifically among girls.

A fourth direction concerns the emotional dimension of god representations and emotional capacities that are a prerequisite for drawing god representations. In all cases, the emotional dimension affects the representations. It is integrated at the cognitive level. Cognitive work is done by children concerning valence. Nevertheless, there is also an emotional impact of the relationship to god and the accompanying relational models. These are highly affect-laden and part of children’s implicit memory systems, influencing the expressions of their god representations (the chapter on attachment is a beginning in the field of studies on the affective dimension of the relationship to god and its impact on drawings).

Notes

- 1.

Why the term god begins sometimes with an uppercase letter G, sometimes with a lowercase letter g, and why it appears sometimes in the singular and sometimes in the plural, is explained in the introductive chapter of this book (Chap. 1, this volume).

- 2.

The international project, Drawings of Gods: A Multicultural and Interdisciplinary Approach to Children’s Representations of Supernatural Agents, is also known in French as Dessins de dieux (DDD), and referred to in this volume simply as Children’s Drawings of Gods.

References

Arteche, A., Bandeira, D., & Hutz, C. S. (2010). Draw-a-Person test: The sex of the first-drawn figure revisited. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37, 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2009.09.002

Barrett, J. L. (2001). Do children experience God as adults do? In J. Andresen (Ed.), Religion in mind: Cognitive perspectives on religious belief, ritual and experience (pp. 173–190). Cambridge University Press.

Barrett, J. L., & Keil, F. C. (1996). Conceptualizing a non-natural entity: Anthropomorphism in God concepts. Cognitive Psychology, 31, 219–247.

Barrett, J. L., Richert, R. A., & Driesenga, A. (2001). God’s beliefs versus mother’s: The development of nonhuman agent concepts. Child Development, 72(1), 50–65.

Barrett, J. L., & Richert, R. A. (2003). Anthropomorphism or preparedness? Exploring children’s God concepts. Review of Religious Research, 44(3), 300–312.

Bovet, P. (1925). Le sentiment religieux et la psychologie de l’enfant. Delachaux et Niestlé.

Boyer, P. (1994). The naturalness of religious ideas: A cognitive theory of religion. University of California Press.

Brandt, P.-Y., Cocco, C., Dessart, G., & Dandarova, Z. (2019). Représentations de dieux dans des dessins d’enfants. In T. Römer, H. Gonzalez, & L. Marti (Eds.), Représenter dieux et hommes dans le Proche-Orient ancien et dans la Bible (OBO 287, pp. 347–370). Peeters.

Brandt, P.-Y., Kagata Spitteler, Y., & Gillièron Paléologue, C. (2009). La représentation de Dieu: Comment les enfants japonais dessinent Dieu. Archives de Psychologie, 74, 171–203.

Brechet, C., & Jolley, R. P. (2014). The roles of emotional comprehension and representational drawing skill in children’s expressive drawing. Infant and Child Development, 23(5), 457–470.

Bucher, A. A. (1992). Entwicklungstheorien der Religiosität als Determinanten des Religionsunterrichts: Exemplifiziert an der Parabel von den Arbeitern im Weinberg (Mt 20, 1–16). Archiv für Religionspsychologie/Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 20, 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1163/157361292x00040

Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1992). Self-regulatory mechanisms governing gender development. Child Development, 63, 1236–1250. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131530

Cassibba, R., Granqvist, P., & Costantini, A. (2013). Mothers’ attachment security predicts their children’s sense of God’s closeness. Attachment and Human Development, 15(1), 51–64.

Chen, W.-J., & Kantner, L. A. (1996). Gender differentiation and young children’s drawings. Visual Arts Research, 22, 44–51.

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19, 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

Dandarova, Z. (2013). Le dieu des enfants: Entre l’universel et le contextuel. In P.-Y. Brandt & J. M. Day (Eds.), Psychologie du développement religieux: questions classiques et perspectives contemporaines (pp. 159–187). Labor et Fides.

Dandarova-Robert, Z., Cocco, C., Astaneh, Z. and Brandt, P.-Y. (in press). Children’s imagination of the divine: Creativity across religions. Creativity Research Journal.

Daniel, G. (1997). Selbst- und Gottesbild: Entwicklung eines Klärungsverfahrens bei Kindern mit Sprachstörungen. Die Blaue Eule.

Davis, E. B., Moriarty, G. L., & Mauch, J. C. (2013). God images and god concepts: Definitions, development, and dynamics. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5, 51–60.

De Roos, S. A., Iedema, J., & Miedema, S. (2001). Young children’s descriptions of God: Influences of parents’ and teachers’ God concepts and religious denomination of schools. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 22, 19–30.

De Roos, S. A., Iedema, J., & Miedema, S. (2004). Influence of maternal denomination, God concepts, and child-rearing practices on young children’s God concepts. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 43, 519–536.