Abstract

Most previous studies on the employment effects of government R&D grants targeting SMEs are characterized by data-, measurement-, and selection problems, making it difficult to construct a relevant control group of firms that did not receive an R&D grant. We investigate the effects on employment and firm-level demand for high human capital workers of two Swedish programs targeted toward growth-oriented SMEs using Coarsened Exact Matching. Our most striking result is the absence of any statistically significant effects. We find no robust evidence that the targeted R&D grant programs had any positive and statistically significant effects on the number of employees recruited into these SMEs, or that the grants are associated with an increase in the demand for high human capital workers. The lack of statistically significant findings is troublesome considering that government support programs require a positive impact to cover the administrative costs associated with these programs.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Innovation policy

- R&D grants

- Statistical matching methods

- High human capital

- Firm growth

- Outcome additionality

1 Background

A surprisingly small number of new ventures and innovative small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) account for a large share of net job creation and productivity growth in the economy (Henrekson & Johansson, 2010). However, due to a lack of financial resources or competitive positions, many SMEs are not able to survive their first years of operations (Nightingale & Coad, 2014; Shane, 2009). As a consequence, targeted R&D grant programs were created as part of industrial policy for most governments in Europe (Becker, 2015). The main goal of these R&D grant programs is to alleviate financial and market pressures while R&D efforts are brought to fruition, thereby increasing the likelihood that these firms fulfill their growth potential.

Job growth tends to be one of the most important reasons why policymakers launch R&D grants toward growth-oriented SMEs, and it is widely regarded as a proxy for the social returns of such government support programs (Cantner & Kösters, 2015). Additional R&D activity is considered to best be captured by an increase in number of employees (Cantner & Kösters, 2015; Wallsten, 2000). A recent literature overview by Dvouletý et al. (2021) indicates that R&D grants toward SMEs in the European Union have been successful in promoting employment growth. However, these authors report significant differences depending on the length of the post-support period, firm size, region, industry, and size of the grant. This implies that we still need more knowledge about the effectiveness of such targeted R&D grant programs, and about whether they are effective in influencing the demand for labor among growth-oriented SMEs (Edler et al., 2013).

Another aim of R&D grants for growth-oriented SMEs is to spur innovative activities, which suggests that such targeted R&D grants should influence firms’ demand for high human capital employees (see e.g., Wolff & Reinthaler, 2008). As noted by Himmelberg and Petersen (1994), R&D expenditures in small firms are generally spent on the salaries of scientists and engineers, or others with the human capital to drive innovation forward. However, as far as we know, few studies have investigated if R&D grants toward growth-oriented SMEs increase the share of highly educated employees among these firms.

We believe that this knowledge gap is based on data-, measurement-, and selection problems. Because selective grants are designed to target specific firms, any observed effects on the outcome of the targeted firms can equally well be a result of the selection process, rather than the effectiveness of the grant. In other words, if the selection of the grant recipients is based on known qualities or the potential of the firm, it is hard to objectively compare them to firms that did not receive a grant. Matching methods are typically used to overcome such selection issues, but they require longitudinal data on both treated (i.e., those firms that receive grants) and non-treated (i.e., those firms that do not receive grants) firms that enable scholars to construct appropriate comparison groups. Such longitudinal data on targeted R&D grants have until recently not been available.

Previous attempts to circumvent the issues of appropriate matching and evaluation of effectiveness include Söderblom et al. (2015), Autio and Rannikko (2016), and Howell (2017). Their studies utilize detailed information on SMEs that applied for R&D support programs, using the outcomes of firms that were rejected in the final evaluation stage to control for selection effects. Söderblom et al. (2015) found that a Swedish R&D grant targeting growth-oriented startups increased the firms’ growth in terms of employees and sales. Further, the grant program made it easier for the firm to attract external financing and overcome “the liabilities of newness” (Stinchcombe, 1965), i.e., their struggle to develop routines, establish relationships with customers, and reach a more efficient scale of operation. Neither Autio and Rannikko (2016) nor Howell (2017) focused on employment growth, but their results provided indications that R&D grants toward growth-oriented SMEs spurred innovation and increased sales.

The strategy to identify the link between receiving a grant and firm-level outcomes relies on the appropriateness of using a comparison group composed of firms that were rejected in the final round of the selection process. The relevance of this identification strategy depends on whether the outcome in the last stage of the decision-making process can be considered as approximately random. Otherwise, the results can be a consequence of an omitted variable that is correlated with the outcome variable and the probability of receiving an R&D grant. However, whether the probability of receiving a grant in the last stage of the decision-making process can be considered as random is highly questionable, since grant-issuing agencies often rely on elaborate ranking processes, usually conducting lengthy interviews to decide which firms will receive an R&D grant.

We estimate the effects of two Swedish government R&D grant programs administered by Vinnova, a Swedish government agency under the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation. These programs seek to promote the development of new products and processes that could bring about new innovations and promote the long-run growth of SMEs. The instruction from the government explicitly states that Vinnova must account for the change in the number of employees that has taken place in SMEs to which they distributed support during the period 2006–2009. This is important as it articulates the effects on employment as a societal aim of these programs (Ministry of Industry, 2013). Note that these programs explicitly aim to promote new innovations and new knowledge, implying that they should have a particular effect on the recruitment of employees with high human capital. Consequently, we study the effectiveness of these grant programs by investigating whether they have a positive effect on the number of employees and the share of highly educated (our measure of high human capital) workers in the targeted firms.

To circumvent the methodological issues discussed above, we use Coarsened Exact Matching to construct a control group from the full population of Swedish firms. Our analyses are based on a unique longitudinal dataset on targeted R&D grant programs in Sweden, which is linked with matched employer–employee data from Statistics Sweden. We find no evidence that the government support programs had any positive and statistically significant effects on the number of employees brought into the targeted firms. This includes a lack of effect during the short-term period in which the firm received grant support, as well as up to 5 years after the support program ended. We also investigate the effect of the government support programs on the demand for employees with higher human capital (as captured by the share of employees that have completed higher education) in the targeted SMEs. This is important because targeted R&D grants might encourage SMEs to recruit workers with higher human capital and higher salaries, rather than increasing their total number of employees. However, we find no robust evidence of any impact of the targeted R&D grant programs on the share of highly educated workers either.

The absence of any statistically significant effects is troublesome considering that targeted R&D grants require a positive impact that at least covers the administrative costs associated with these programs. Our results thus question the relevance of implementing government support programs targeting SMEs with high-growth potential. We believe that our findings challenge the more established norms that are widely accepted in terms of providing government grants to highly innovative firms. In illustrating the potential lack of impact of these grant programs, we hope to raise potential issues that relate to the selection mechanisms involved in such grant processes and consider alternative measures and outcomes of these grants.

2 Effects of Targeted R&D Grant Programs on Labor Demand

There is an extensive literature evaluating different aspects of targeted R&D grant programs. Overall, this literature illustrates an equivocal state of affairs concerning the overall impact and effects of these R&D grants. For example, some support programs seem to yield positive results on innovation and growth, while the results from other programs are less clear, and some even demonstrating negative effects.

Dvouletý et al. (2021) provide a review of empirical studies that have investigated the effects of targeted R&D grants on firm performance in 28 European Union member countries. The authors only include studies that employ techniques to estimate the counterfactual outcome of the grants, such as propensity score matching (PSM) and regression discontinuity design (RDD). The review covers several different outcome variables, including employment growth but not demand for skilled labor. The results show that 20 studies have investigated the effects of targeted R&D grants on employment growth, and that 18 of these studies report positive employment effects. This indicates that R&D grants targeted toward SMEs can be successful in promoting employment growth. However, the results also reveal significant differences depending on the length of the post-support period, firm size, region, industry, and size of the grant.

Zúñiga-Vicente et al. (2014) offer another extensive overview of the impact of R&D grants, based on a compilation of 77 studies from different countries. Their main conclusion is that the results are rather mixed in terms of overall impact, but that there are four clear tendencies. First, the crowding-out effect of a support scheme, i.e., the decline in private investments following a government grant, seems to be affected by the financial restrictions (e.g., bank contacts, ability to attract venture capital) faced by the individual firm. Second, the effect of support programs differs between basic research and development projects. Third, the impact of the grant is most likely larger for smaller R&D projects or when the grant is relatively large compared to firm sales. Finally, there is a time lag before any positive effects of a grant are realized.

Koski and Pajarinen (2013) argue that the time lag between a grant and its impact tends to be somewhere between one and three years. One problem with time lags is that the more time that passes between grant receipt and outcome, the greater the risk that the causal impact of the grant is contaminated by unobserved factors that take place during the post-treatment period (Mian & Sufi, 2012). However, when investigating the effects of R&D grants on firms’ demand for labor, Koski and Pajarinen (2013) found that the R&D grant had a positive impact on employment during the time of the support program but diminished after the support program ended. Previous studies also indicate that the effects of targeted R&D grants seem to be larger for small firms as compared to large firms (see e.g., Bronzini & Iachini, 2014).

Söderblom et al. (2015) try to address the selection problem when analyzing the effects of a targeted R&D grant program among Swedish innovative startups by comparing data on firms that received support with those that applied for funding but were rejected at the last stage of the decision-making process. Their identification strategy is thus to compare the development of firms that received subsidies (treatment group) with firms that applied but were rejected in the last instance (control group). The logic is that those firms who were the last out offer the closest comparison to the firms that received grants. The final treatment group consists of 130 firms that received funding during 2002–2008, compared with 154 firms in the control group that were rejected at the last stage. The results indicate that the targeted R&D grants had a positive and statistically significant effect on employee and sales growth, implying that small startups grants can be an efficient way of promoting the growth of new innovative companies.

A similar comparison strategy was used by Autio and Rannikko (2016) when investigating the effects of a Finnish R&D program also focusing on growth-oriented new ventures. Although not focusing on employment effects per se, they found that firms participating in the R&D program increased sales by 120% compared to the control group of non-targeted firms. Howell (2017) analyzed data on ranked applicants to the US Department of Energy’s SBIR grant program, finding a large positive effect of the R&D grant on revenues and patenting. However, this study does not focus on the effects of targeted R&D grants on employment nor on demand for skilled labor.

An implicit assumption behind the identification strategy described above is that there are great similarities between those firms that were supported, and those that almost received support from the program. This kind of identification strategy is thus only valid if the firms that received support were randomly chosen at the last stage of the selection process (Angrist & Pischke, 2008). However, government agencies tend to select those firms that receive support based on metrics and data from personal interviews and expert group evaluations. It is thus likely that there is a systematic difference between the treatment and control group based on the subjective perceptions of these interviews and evaluations, and that those firms that received support would have performed better than the treatment group even in the absence of support.

Note also that the treatment and control groups might be different even if the firms are endowed with similar observable characteristics. The selection of the firms that received support might depend on factors that are unobservable to the researchers but are correlated with the future growth of the companies. If we believe that the decision-makers select and recommend firms that have a higher probability of success, then we would expect that these firms perform better over time regardless of whether they receive subsidies.

3 Data and Programs Analyzed

To estimate the average treatment effect of a targeted grants program (ATT), information is required about the targeted firms, the amount they received, and when they received it. We obtain this information from the Micro Database of Government Supports to Private Business (MISS), which is a comprehensive dataset on government support programs compiled by Myndigheten för tillväxtpolitiska analyser och utvärderingar (the Swedish Government Agency for Growth Policy Analysis). The dataset includes a unique firm identification number, which makes it possible for us to merge MISS data with a matched register-based employer–employee dataset from Statistics Sweden that covers all limited liability firms in Sweden. This dataset includes information on number of employees, investments, sales, value added, industry affiliation, and educational attainment of workers, among other variables.

We investigate the effects of two R&D grant programs included in MISS, Vinn Nu (Win Now) and Forska & Väx (Research & Grow). These programs were chosen because they both target growth-oriented innovative SMEs with the purpose of increasing innovative activities and job growth. The programs are administered by Vinnova, a Swedish government agency under the Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation.

Vinn Nu was initiated in 2002 with the logic that there was a lack of private funding for young R&D-intensive firms. This program targets innovative startup companies with the objective of improving their conditions for survival, helping the commercialization of innovations, and attracting external capital. The expectation is that this program will help these companies to grow and become more successful businesses. These grants do not require a firm cash match, but the firm must have developed a product, method, or service that has not yet reached the market in order to qualify for the grant. The maximal amount that a firm could receive during the study period was 300,000 Swedish krona (SEK).Footnote 1

Applications to Vinn Nu are first evaluated by an internal group of experts within Vinnova and the Swedish Energy Agency. Approximately half of the applications go to a second round, where they are judged by a panel of external experts. The final candidates are then called to an interview before Vinnova decides which firms will receive the grant (Samuelsson & Söderblom, 2012).

Forska & Väx was launched in 2006 and targets SMEs with existing R&D activities. The program seeks to stimulate innovation-driven growth for the targeted companies. In contrast to Vinn Nu, Forska & Väx is a matching grant that requires at least 50% co-financing of the R&D investments by the targeted firms. The applicants could apply for a maximum of five million SEK, and they were required to have at least one million SEK in sales (or in share capital) and no more than 250 employees to be eligible for funding. Firms also needed to demonstrate the potential to improve on or develop new products. Some firms also applied for a smaller grant to develop an implementation plan of the larger R&D project within the scope of the program. In this case, firms could apply for a maximum of 300,000 SEK without co-financing. This smaller grant only required applicants to have achieved 300,000 SEK in sales.Footnote 2

According to the calls for submissions of these programs, they both seek to promote the development of new products and processes that could bring about new innovations and promote job growth among SMEs. This is also emphasized by the fact that the agency had to report “change in turnover, employment and value added” of the supported companies to the government (Ministry of Industry, 2013). The programs are thus designed to increase the demand for labor and the purpose is also to help companies run development projects. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the grants should facilitate the recruitment of key individuals with the skills and abilities to innovate and thereby increase the share of employees with higher human capital. Hence, if effective, these grants should have a positive effect on the number of employees and the share of skilled workers in the targeted SMEs.

In Table 1, we present the number of yearly grants along with average grant size (SEK) from Vinn Nu and Forska & Väx, respectively, during the period 2002–2010. Since a grant is sometimes paid out in parts, it is possible for individual grants to encompass multiple payouts. An average of 14 grants per year were made under Vinn Nu. Samuelsson and Söderblom (2012) noted that 1309 firms applied for support from Vinn Nu during 2002–2011, which means that approximately 10% of all applicants received a grant.

Forska & Väx has approximately ten times more grants per year compared to Vinn Nu. The average amount paid out is also almost four times higher under the Forska & Väx program. Targeted firms under Vinn Nu received, on average per year, received 178,911 SEK during 2002–2010. This can be compared with 596,659 SEK, the average amount paid out under Forska & Väx, yearly, during the study period.

4 Empirical Method

4.1 Matching

The ideal goal when investigating the effects of targeted R&D grants toward SMEs is to get an estimate of the counterfactual outcome, i.e., to answer the “what would have happened to the treated firms if they not had received the R&D grant?” question.Footnote 3 Since firms are not randomly selected by the programs, it is central to identify a non-treated control group of firms that is as similar to the treated firms as possible across all relevant dimensions. Systematic differences between the control and treatment groups may otherwise bias the results. There are different ways to tackle this kind of selection issue, such as regression discontinuity design, instrumental variables, natural experiments, difference-in-difference, and various matching methods. Each alternative is associated with both advantages and disadvantages.

For a firm i, let Ti = 1 if it is treated, and Ti = 0 if it is not, the effect on some outcome variable Yi can then be described as a function of Ti such that:

For treated firms, the counterfactual is given by Yi(0). The most effective method (if there is one) often depends on the nature of the problem and the data available. We have detailed information about both the treated and non-treated firms, as well about the grants, which have led us to opt for a matching method to approximate Yi(0).

We let X be a vector of characteristics for N non-treated firms that explain Yi along with the probability of receiving a grant. To approximate Yi(0), matching methods strive to limit the number of non-treated firms in the dataset to M ≤ N such that the characteristics between the limited set of matched firms (XM) become as similar as possible to the characteristics of the treated firms (XT). Given the distance function d(·, ·) we would like to have d(XM, XT) ≅ 0 (Iacus et al., 2011). Ideally, we would want to have d(XM, XT) = 0, which corresponds to an exact matching between the treated and control firms with the same level in their covariates. Such ideal conditions, however, are rarely met in practice, especially for continuous covariates such as performance and profitability.

To identify the control group of firms whose covariates are as similar as possible to the treated firms, we rely on the matching methods of Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) developed by Iacus et al. (2011, 2012). Since small differences between the covariates for treated and control firms do not necessarily reflect economically meaningful differences, CEM allows for a coarsening of the variables upon which an exact matching can be performed. Any imbalance between the covariates of the treated and control firms is thus decided upon beforehand. This implies that the maximum imbalance that may result after the matching is bounded by the width of the coarsening bins.

This type of matching has some advantages (Blackwell et al., 2009; Iacus et al., 2011, 2012), especially compared to the more commonly used Propensity Score Matching (PSM) (see King & Nielsen, 2015 for example). Most importantly, the CEM estimator satisfies the property of being monotonically imbalance bounding (MIB), which means that total balance can be improved by adjusting the balance of a single covariate. This property, for example, is not shared with PSM, where there is no way of knowing if the total balance in the matching has been improved by ameliorating the balance of a single covariate or by adding or removing covariates. The MIB property of CEM greatly facilitates our aim to, via matching, find a more appropriate control group consisting of untreated firms, contrary to PSM, which merely “works when it works, and when it does not work, it does not work (and when it does not work, keep working at it)” (Ho et al., 2007, p. 219).

We include different variables in X to accompany our two outcome variables. First, the number of employees corresponds to the firm’s demand for labor. The basic model of labor demand can be derived from the firm’s cost function as a function of the return to factors and value added (Hijzen & Swaim, 2008). In this case, we include wages and value added, measures of firm skill intensity and the profitability of the company. The latter can be seen as a beauty contest indicator that may influence the probability of being selected by the programs. Second, to choose the matching variables X for the number of employees with high skills, we rely on models of firms’ relative demand for skills, which similarly can be derived from cost minimization under given factor prices and output (Hansson, 2000).

We present descriptive statistics for our outcome variables and the variables included in X in Table 2. The results show that the treated firms on average have approximately 20 employees and that about 55% of their employees had completed higher education during the pretreatment period. The corresponding average values for the post-treatment period suggest that the treated firms increased their number of employees by approximately 3% and that their share of workers with post-tertiary education increases by approximately 2 percentage points. Note also that the treated firms on average increase sales and value added by about 10% after receiving an R&D grant.

To decide upon the coarseness of the respective variable, we use the generic algorithm proposed by the CEM-program cem in Stata. This means that the matching process gives a relatively high weight to the best-matched control firms (Blackwell et al., 2009). Table 3 presents the univariate L1 distance before and after the cem matching for our treatment and control group of firms, respectively. As can be seen in Table 3 below, matching reduces the differences unilaterally, except for profits.

4.2 A Difference-in-Difference Analysis

After we constructed a control group using CEM, we turned our attention to estimating the average treatment effect of the treated firms. More formally, we want to investigate:

The reason why we cannot simply compare the average performance between the control group and the treatment group is that we want to check for any differences between XC and XT that remain after matching. We therefore rely on a difference-in-difference model to investigate the effect of the government support programs on our outcome variables number of employees and share of employees that have completed a higher education. The estimated model can in our fixed-effect set-up be specified as follows:

where Treat is a dummy variable for the treatment (i.e., receiving a grant) or alternatively, the amount of money paid out to the firm. If the responses from the targeted firms are immediate, the effects of the grant should be captured first and foremost by this variable. Post_treat is a post-treatment indicator taking the value one in the years following a treatment and zero otherwise. Given that the impact of the grant comes with a delay, the impact of the grant is captured by this variable. The set of control variables are included in the vector X, μi captures time-invariant firm effects, γt captures period-specific effect, and ε is white noise.

In the labor cost equation, it is standard to account for the cost of adjusting the number of employees. Adjustment costs introduce state dependence in the labor demand equation, which from a modeling perspective means that we fit a dynamic lag to the labor demand model in Eq. (2). The dynamic panel data model is estimated using a system GMM estimator (Blundell & Bond, 1998), while relative demand for skills is estimated using a fixed-effect model.

One critique of matching is that it can only account for selection to the extent it occurs through observed variables. In the basic model, we therefore include a parameter αi that captures unobserved variation specific to the firms and the period under study. This eliminates selection bias on unobserved variables that do not vary within firms over the period under study. However, bias might still arise from firm-specific time-variant characteristics that we are not able to control for in the empirical analysis.

We consider two extensions of the basic model. First, we investigate if the treatment effect of the grants is moderated by the size of the targeted firms. Second, to investigate dynamic aspects of grant programs, we estimate the effect of the targeted R&D grant up to 5 years after the support period ended.

5 Results

We present results for three different groups: (i) Treated firms only; (ii) Treated firms against a matched control group (which is our preferred estimator); and (iii) Treated firms against an unmatched control group of all non-treated firms. Differences between (ii) and (iii) can be seen as a signal of selection into the support programs and of how the treated firms deviate from the average firm. We also include an interaction effect to investigate how the effects of the targeted R&D grants vary with firm size.

5.1 Effects of Targeted R&D Grants on Number of Employees

Our results for the number of employees, i.e., labor demand, are presented in Table 4. Note that we estimate two specifications for each of the three models (i–iii). In the first, referred to as our basic specification (columns 1, 3, and 5), we estimate the DiD regression specification in Eq. (2), and in the second specification, we present an extended model in which we re-estimate the regression with the treatment effects interacted with firm size. This is of interest because previous studies (e.g., Bronzini & Iachini, 2014) have indicated that the effects of government support programs might be more pronounced for small firms.

Beginning with the basic results (columns 1–3), we find no indications that the support programs have increased employment, neither during the support period nor after the program has ended. When comparing treated firms with the population of all non-treated firms, the post-support effect of the programs is negative and statistically significantly different from zero. Thus, firms that receive support do not grow faster in terms of number of employees compared to the average firm. On the contrary, they grow slower than the average firm when the support program ends.

In the extended models, the marginal effect of the grants is a combined effect of the direct effect and the interaction term that allow the results to vary with respect to firm size. The treatment effect can therefore be seen as the impact of the grant on an imaginary firm with zero employees, whereas the interaction term describes how the effect changes with firm size.

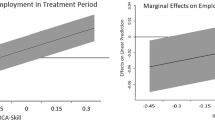

To interpret the interaction effect in the extended model with greater ease, we display the marginal effect and how it varies with firm size in Fig. 1. Firm size is measured as the natural logarithm of value added, ln(va). Here, we choose to only present the post-treatment effect of the grants from the interaction models in our preferred model, i.e., the matched DiD-model (i.e., column 5 in Table 4), over the observed range of firm sizes.

The plots show that the marginal post-treatment effect of the grants on the number of employees in general is not statistically significant regardless of firm size. There is a tendency that the effect of the grants increases with firm size and there is a negative and significant post-treatment effect for the smallest firms. These results deviate to some extent from the literature, where the most positive effects of firm support programs in general are found for small firms.Footnote 4

5.2 Effects of Targeted R&D Grants on Employees with Higher Education

One aim of the programs under study is to help firms manage R&D projects. It is therefore expected that these grants should encourage firms to invest more in skilled labor, and thus increase their relative demand for workers with higher human capital. Hence, even without any impact on the total number of workers, it is possible that firms that are supported by the government programs would substitute less qualified workers for workers with higher human capital.

Following Hansson (2000), we estimate how the demand for highly educated labor has been affected by the support programs. The results are presented in Table 5, showing no positive effect of the support programs on the relative demand for workers with post-secondary education in our main model specifications (columns 1–3). In fact, there are no estimates that are statistically significantly different from zero during the program period or after the program has ended. This implies that there is no effect in the short- or longer-term for these grants.

In the extended models (columns 4–6), we observe a negative post-treatment effect when comparing treated firms with their own growth pattern and with all other non-treated firms. The interaction term, however, loses its significance when we compare treated firms with the matched control group (column 5).

To capture the marginal effect of the grants on demand for skilled labor over the firm size distribution (as we did with labor demand in Fig. 1), we compare the treated firms with a matched control group. However, the results are not statistically significant, and we can therefore not conclude that the effects of the targeted R&D grant programs on the demand for employees with higher education are dependent on firm size.Footnote 5

5.3 Post-Treatment Effects

So far, we have presented the results when estimating the averaged post-treatment effects of the support programs. The reported estimated effects thus display the average effect of the programs after the grants are no longer paid out to the companies. One concern is that there might be a non-linear response from the targeted firms that is not captured by these estimates. For example, the effects of the support programs on employment growth and demand for highly educated employees can, say, take off after some time. This means that significant results for individual years might be wiped out when aggregating the results over time. As a robustness check, we therefore also estimate yearly post-treatment effects.

The results from our year-by-year post-treatment analysis are presented in Fig. 2 (labor demand) and Fig. 3 (demand for highly educated employees). We choose to present the results from our preferred model specification, i.e., our DiD-estimations using a control group of matched firms. All point estimates and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals are displayed up to 5 years after the support programs have ended.

We find no tendencies of a positive post-treatment effect on demand for labor (Fig. 2) and, if anything, the results are on the negative side. Thus, our year-over-year analysis confirms the finding that R&D grants had no post-treatment effects on the targeted SMEs. However, when investigating the relative demand for skilled labor, the estimate is positive and significant at the 5% level during the first post-treatment year and remains positive at the 10% significance level during the following year.

There are thus some indications that the targeted R&D grants under study increased relative demand for high human capital labor during the first two post-treatment years. This implies that firms that receive targeted R&D grants increase their share of workers with higher education even though no effects on total employment are detectable. However, the positive significance size ceases to exist after 3 years.

6 Discussion and Conclusions

Government support programs targeted toward innovative SMEs have become more common in recent years, and these programs are generally considered to be important in increasing innovative activities, and consequently employment growth, among growth-oriented SMEs (Bradley et al., 2021).

A challenge when evaluating these targeted R&D grant programs is how to estimate the counterfactual effect, i.e., the development of firms that were supported in the absence of receiving any government R&D grant. SMEs are not randomly selected by the programs; rather, R&D grants are often awarded to the most promising growth-oriented firms based on a combination of criteria. Hence, assessments might conclude that government support programs have been highly effective in increasing firms’ labor demand, even though targeted SMEs would have increased their number of employees and workers with higher education regardless of whether they received the R&D grant or not.

This selection problem is often handled using a matching technique, thereby comparing firms that received support with similar firms that did not receive any targeted R&D grants. We rely on Coarsened Exact Matching to investigate the effects of two growth-oriented support programs in Sweden targeted toward innovative SMEs, making it possible to provide a more robust approach to matching. Our analyses are made possible due to access to a unique micro database on government firm support programs, compiled by the Swedish Government Agency for Growth Policy Analysis. This database alleviates the previous data acces-based concerns by finding appropriate matching firms.

The most striking result of our analyses is the absence of statistically significant effects. We find no robust evidence that the government support programs had any positive and statistically significant effects on the number of employees brought into these growth-oriented SMEs. Additionally, there is not any robust evidence of an impact of the grants on the skill composition of the labor force.

The lack of statistically significant findings is troublesome considering that government support programs require a positive impact to cover the administrative costs that are associated with these programs. When the expected return of engaging in nonproductive entrepreneurship is high, entrepreneurs might also use time and resources to apply for government firm support programs instead of developing their businesses (Baumol, 1990). Firm support programs can thus crowd out more productive investments.

Our findings complement recent papers (e.g., Autio & Rannikko, 2016; Howell, 2017; Stevenson et al., 2021; Söderblom et al., 2015) that found significant positive effects of government subsidies toward innovative SMEs. Their approach of using firms that applied for, but did not receive, funding as a control group has led to varying outcomes. We cannot exclude that their results are due to an inherent selection bias in their analysis since the treatment group has been judged as more promising than the control group. This suggests that the treatment group would have performed better than the control group even without a grant.

The lack of significant employment effects of the government support programs that we investigate is troublesome considering that policymakers often justify targeted R&D grants with the need to correct market failures and promote job growth. We believe that the lack of significant results points toward the challenges involved in using targeted R&D grants as a way of promoting future growth among SMEs. Coad et al. (2014), for example, noted that it is very difficult to point out which firms are going to be fast growers in the future, suggesting that government support programs are unlikely to target potential high-growth firms that would not grow without support. This is consistent with previous evidence that firm growth, to a large extent, can be considered random (Coad et al., 2013), thereby making it extremely hard for policymakers to determine what characterizes SMEs that need an R&D grant to promote job growth and demand for highly skilled labor.

Our findings may also reflect the heterogeneous nature of SMEs, even highly innovative ones. Reflecting the variety of innovative firms may begin to lessen the randomness of the next stages of development, by including truly new ventures with their initial product offering, developing, or commercializing a new-to-the-world technology vs. leveraging innovation from elsewhere, younger ventures that are highly technical but which may not rely on traditional R&D functions, or even more established small firms looking to expand. One notion advanced by Mason and Brown (2013) is to focus on outcomes that help support retaining winners rather than simply picking winners. This approach would at a minimum remove some sources of variance among firms applying for these types of growth grants.

As an alternate explanation, it may be that the highly influential interviews and expert evaluations of those firms under consideration are ineffective. There is currently a dearth of empirical evidence that scrutinizes the questions asked, of whom they are asked, and how the answers are analyzed as part of the application process—or what objective metrics they employ to rate the attractiveness of these potential grant recipients. Even when professional investors have tremendous difficulties in predicting the future outcomes of high-potential but risky ventures, policymakers maybe even less equipped to make these evaluations or provide monitoring of the funding over time (Lerner, 2009). The opacity of this evaluation process and the inconclusive results of their benefit brings into question whether and how robust and objective decision rubrics can effectively be employed.

More broadly, the absence of positive results in our study brings into question whether government support programs toward SMEs can be justified, given that they are associated with high administrative costs, increased incentives for rent-seeking behavior among entrepreneurs, and crowding-out effects on alternative investments that could be more beneficial for society (Bradley et al., 2021). The incentive and ability for researchers to publish results that are statistically significant (Møen & Thorsen, 2017) might also have led to an overconfidence in policymakers’ abilities to influence the future growth and human capital of SMEs, when the non-findings of policy effects are rarely published.

Our study does not come without limitations, however. Even though we use a matching method that is at the research frontier, our results might still be biased if unmeasured variables are correlated with job growth and the likelihood of receiving a targeted R&D grant. We believe that the approach used by Söderblom et al. (2015) can provide more reliable estimates if the policymakers in the last stage of the decision-making process would randomize which firms receive an R&D grant. The advantage of using a randomized field experiment is that the outcome variable cannot affect the probability of receiving an intervention, which means that we know that it is not the intervention that affects the outcome variable. Randomization also implies that there is no systematic connection between the probability of belonging to the intervention group and observable and non-observable factors (Burtless, 1995).

Randomized control trials (RCT) have recently been used in the UK to evaluate the effects of targeted R&D grants (Bakhshi et al., 2015; Roper, 2020), and McKenzie (2017) provides fascinating evidence from an RCT in Nigeria on the effects of public grants following a national business program competition. We believe that more such studies are needed to provide more robust evidence on the effectiveness of government support programs, although we recognize that introducing randomization may be a challenge for policymakers to justify. But it may also potentially remove concerns regarding implicit bias (or crony capitalism at worst; Klein et al., 2021) from selecting from among a group of SMEs that otherwise meet or exceed the criteria for a grant.

Another fruitful area for future research is to more closely evaluate whether the effects of the grants are related to underlying unobservable or difficult-to-quantify factors, such as differences in how well companies are integrated into local business conditions, or the presence of positive spillovers from other companies. These factors are found to be important for growth among innovative firms but create potential challenges to identify and categorize a priori. More research is also needed on whether certain types of targeted R&D grants are more effective than others. Certainly, innovative activities among SMEs come in many shapes and sizes (McKelvie et al., 2017), where many of the most impactful aspects that lead to growth do not appear as formal R&D activity. As such, a heterogeneity analysis could deepen the understanding of the conditions under which the opportunities for positive effects of government support programs are greatest across different aspects of innovative activities beyond R&D.

Instead of focusing on a small group of growth-oriented R&D-intensive SMEs, it may also be more important to focus research and policy measures on what is needed to stimulate growth among SMEs that do not grow, or at best grow marginally. As noted by Bornhäll et al. (2015), the existence of growth barriers is likely to prevent these firms from growing, while potential high-growth firms might grow despite the existence of such growth barriers. General policy measures aimed at low-growth SMEs (e.g., simplification of rules, reduced labor costs, more liberal employment protection legislation, etc.) can thus be more effective in promoting job growth than targeted R&D grants toward SMEs that are considered potential high-growth firms. This corresponds to the analogy in Coad et al. (2014, p. 92), in which tourists on safaris are focused on beautiful gazelles but fail to see the importance of the dung beetle in maintaining the health of the ecosystem.

Note also that we have been investigating the effects of two Swedish R&D grants that are administrated by Vinnova and targeted toward growth-oriented SMEs. The lack of significant effects does not mean that R&D grants never work. As noted in our literature review, there is substantial evidence that grants can indeed be helpful for SMEs when looking at different outcome variables. Other types of programs can also be successful in promoting employment growth, while similar R&D grants might be efficient under other institutional contexts (e.g., in other countries). The unique nature of growth-oriented ventures in Sweden has been noted in the literature (McKelvie et al., 2021).

Another possible interpretation of our non-significant results is that the R&D grants under study usually work, but that the government agency administering the programs is not designing or executing the programs adequately. The R&D grants might, for example, work better if they were given to larger firms or a smaller set of higher-quality applicants. Our study does not currently investigate these alternate models, but we do encourage others to take up this task. We have furthermore focused on the employment effects of targeted R&D grants; it is possible that such programs have a higher impact on other outcome variables (see e.g., Howell, 2017).Footnote 6 The external validity of our findings is thus low, and interpretations in other contexts should be made with care. This highlights the importance of gathering more robust evidence on the effects of government support programs that are targeted toward SMEs with growth potential.

While we fully accept that the development of growth-oriented SMEs is important to the economy, we also recognize that more transparent and methodologically sophisticated tools are needed to more fully evaluate the effectiveness of current practices, such as R&D grant programs. Our intent with this study is to illustrate two programs that are well-intended but that do not seem to have the desired impact, and to offer thoughts on the conditions through which we as scholars can better make these determinations of effectiveness. In doing so, we hope to contribute to a more robust and systematic understanding of how government policies further—or fail to further—entrepreneurship.

Notes

- 1.

This corresponds to approximately US$40,200 based on the average SEK/USD exchange rate (0.1340) during the period 2002–2010.

- 2.

These development grants represent a small share of the Forska & Väx program.

- 3.

Henceforth, we refer to firms that receive a grant from either Vinn Nu or Forska & Väx during the period as treated firms, and firms that do not receive support as non-treated firms. All results presented are for both programs. Results are qualitatively similar if we conduct separate estimations for each program. These results are not reported here, but are available from the authors upon request.

- 4.

The marginal effect of the grants during the duration of the program is not statistically significant anywhere and therefore not depicted in a figure.

- 5.

Results are available on request.

- 6.

Note that the authors have investigated the effects of these R&D grants on sales and labor productivity in a Swedish report for the Swedish Government Agency for Growth Policy Analysis (Daunfeldt et al., 2014). Their results indicate no statistically significant effects on labor productivity, while the government support programs increased sales by 20% during the first post-support year. The latter effect is, however, limited to firms with at most six employees. No positive and statistically significant effect is found for larger firms.

References

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. S. (2008). Mostly harmless econometrics. Princeton University Press.

Autio, E., & Rannikko, H. (2016). Retaining winners: Can policy boost high-growth entrepreneurship? Research Policy, 45(1), 42–55.

Bakhshi, H., Edwards, J. S., Roper, S., Scully, J., Shaw, D., Morley, L., & Rathbone, N. (2015). Assessing an experimental approach to industrial policy evaluation: Applying RCT+ to the case of creative credits. Research Policy, 44(8), 1462–1472.

Baumol, W. J. (1990). Entrepreneurship: productive, unproductive and destructive. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), 893–921.

Becker, L. (2015). Effectiveness of public innovation support in Europe. Does public support foster turnover. In Employment and labour productivity? Discussion papers, Center for European Governance and Economic Development Research (Vol. No. 236). University of Goettingen.

Blackwell, M., Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2009). Cem: Coarsened exact matching Stata. Stata Journal, 9(4), 524–546.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Bornhäll, A., Daunfeldt, S. O., & Rudholm, N. (2015). Sleeping gazelles: The unseen job creators? In A. C. Corbett, J. A. Katz, & A. McKelvie (Eds.), Entrepreneurial growth: Individual, firm, and region. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Bradley, S. W., Kim, P. H., Klein, P. G., McMullen, J. S., & Wennberg, K. (2021). Policy for innovative entrepreneurship: Institutions, interventions, and societal challenges. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 15(2), 167–184.

Bronzini, R., & Iachini, E. (2014). Are incentives for R&D effective? Evidence from a regression discontinuity approach. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 6(4), 100–134.

Burtless, G. (1995). The case for randomized field trials in economic and policy research. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2), 63–84.

Cantner, U., & Kösters, S. (2015). Public R&D support for newly founded firms–effects on patent activity and employment growth. Journal of Innovation Economics Management, 1(16), 7–37.

Coad, A., Frankish, J., Roberts, R. G., & Storey, D. J. (2013). Growth paths and survival chances: An application of Gambler’s ruin theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 615–632.

Coad, A., Daunfeldt, S. O., Hölzl, W., Johansson, D., & Nightingale, P. (2014). High-growth firms: Introduction to the special section. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(1), 91–112.

Daunfeldt, S. O., Gustavsson Tingvall, P., & Halvarsson, D. (2014). Företagsstöd till innovativa små och medelstora företag: En kontrafaktisk effektutvärdering, report 2014:26, the Swedish Government Agency for Growth Policy Analysis.

Dvouletý, O., Srhoj, S., & Pantea, S. (2021). Public SME grants and firm performance in European Union: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Small Business Economics, 57(1), 243–263.

Edler, J., Cunningham, P., Gök, A., & Shapira, P. (2013). Impacts of innovation policy: Synthesis and conclusions–compendium of evidence on the effectiveness of innovation policy intervention project. Nesta, 2013, June. UK.

Hansson, P. (2000). Relative demand for skills in Swedish manufacturing: Technology or trade? Review of International Economics, 8(3), 533–555.

Hayakawa, K. (2009). First difference or forward orthogonal deviation-which transformation should be used in dynamic panel data models: A simulation study. Economics Bulletin, 29(3), 2008–2017.

Henrekson, M., & Johansson, D. (2010). Gazelles as job creators: A survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Business Economics, 35(2), 227–244.

Hijzen, A., & Swaim, P. (2008). Offshoring, Labour Market Institutions and the Elasticity of Labour Demand.The University of Nottingham, Research paper series, No. 2008/05.

Himmelberg, C. P., & Petersen, B. C. (1994). R&D and internal finance: A panel study of small firms in high-tech industries. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 76(1), 38–51.

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2007). Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Analysis, 15(3), 199–236.

Howell, S. T. (2017). Financing innovation: Evidence from R&D grants. American Economic Review, 107(4), 1136–1164.

Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2011). Multivariate matching methods that are monotonic imbalance bounding. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 106(493), 345–361.

Iacus, S. M., King, G., & Porro, G. (2012). Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Political Analysis, 20(1), 1–24.

King, G. & Nielsen, R. (2015). Why propensity scores should not be used for matching. Copy at http://j.mp/1sexgVw Export BibTex Tagged XML Download Paper, 481.

Klein, P., Holmes, R. M., Foss, N., Terjesen, S., & Pepe, J. (2021). Capitalism, cronyism, and management scholarship: A call for clarity. Academy of Management Perspectives, in print. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2019.0198.

Koski, H., & Pajarinen, M. (2013). The role of business subsidies in job creation of start-ups, gazelles and incumbents. Small Business Economics, 41(1), 195–214.

Lerner, J. (2009). Boulevard of broken dreams. Princeton University Press.

Mason, C., & Brown, R. (2013). Creating good public policy to support high-growth firms. Small Business Economics, 40(2), 211–225.

McKelvie, A., Brattström, A., & Wennberg, K. (2017). How young firms achieve growth: Reconciling the roles of growth motivation and innovative activities. Small Business Economics, 49(2), 273–293.

McKelvie, A., Brattström, A., & Dennis, W. J., Jr. (2021). What do they think and feel about growth? Examining small business managers’ attitudes towards growth in the United States. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 15, e00243.

McKenzie, D. (2017). Identifying and spurring high-growth entrepreneurship: Experimental evidence from a business plan competition. American Economic Review, 107(8), 2278–2307.

Mian, A., & Sufi, A. (2012). The effects of fiscal stimulus: Evidence from the 2009 cash for clunkers program. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(3), 1107–1142.

Ministry of Industry. (2013). Regleringsbrev för budgetåret 2014 avseende Verket för innovationssystem inom utgiftsområde 24 Näringsliv, Regeringsbeslut 2013-12-12.

Møen, J., & Thorsen, H. S. (2017). Publication bias in the returns to R&D literature. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 8(3), 987–1013.

Nightingale, P., & Coad, A. (2014). Muppets and gazelles: Political and methodological biases in entrepreneurship research. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23(1), 113–143.

Roper, S. (2020). Using RCTs as a research method for SME policy research: The UK experience. In G. In Saradakis & M. Cowling (Eds.), Handbook of quantitative research methods in entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Samuelsson, M., & Söderblom, A. (2012). Statlig finansiering och dess påverkan på innovativa småföretag: En beskrivande studie av VINN NU-programmet, Rapport, Handelshögskolan i Stockholm.

Shane, S. (2009). Why encouraging more people to become entrepreneurs is bad public policy. Small Business Economics, 33, 141–149.

Stevenson, R., Kier, A. S., & Taylor, S. G. (2021). Do policy makers take grants for granted? The efficacy of public sponsorship for innovative entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 15(2), 231–253.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 142–193). Rand McNally.

Söderblom, A., Samuelsson, M., Wiklund, J., & Sandberg, R. (2015). Inside the black box of outcome additionality: Effects of early-stage government subsidies on resource accumulation and new venture performance. Research Policy, 44(8), 1501–1512.

Wallsten, S. J. (2000). The effects of government-industry R&D programs on private R&D: The case of the Small Business Innovation Research program. The Rand Journal of Economics, 31(1), 82–100.

Wolff, G. B., & Reinthaler, V. (2008). The effectiveness of subsidies revisited: Accounting for wage and employment effects in business R&D. Research Policy, 37(8), 1403–1412.

Zúñiga-Vicente, J. Á., Alonso-Borrego, C., Forcadell, F. J., & Galán, J. I. (2014). Assessing the effect of public subsidies on firm R&D investment: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 28(1), 36–67.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Swedish Competition Authority (grant number 376/2016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Daunfeldt, SO., Halvarsson, D., Tingvall, P.G., McKelvie, A. (2022). Do Targeted R&D Grants toward SMEs Increase Employment and Demand for High Human Capital Workers?. In: Wennberg, K., Sandström, C. (eds) Questioning the Entrepreneurial State. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, vol 53. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94273-1_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94273-1_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94272-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94273-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)