Abstract

Sexual activity is an important facet of social functioning and quality of life (QoL) reflected in its inclusion in the World Health Organization’s generic, 26-item, quality of life instrument, the WHOQOL-BREF, in the item “how satisfied are you with your sex life?” Several instruments designed to assess sexual activity, function or QoL have been developed, varying in their scope, measurement properties, and applicability to certain populations. Evidence from literature reviews of instruments was synthesized to (a) identify generic self-administered instruments, which have been developed for research or clinical practice in adults and (b) to investigate their scope, psychometric properties, and applicability. We then considered these methods together with emerging Quality of Life Technologies. In total, 110 instruments were identified via nine reviews and 31 generic instruments were retained. There was a good evidence of the instruments’ internal consistency and reliability, but limited evidence of their responsiveness to change. While 31 instruments provide an adequate assessment of function/sexual QoL, fitting with COSMIN guidance, their scope varied and only three of these were developed since the revision of the definition of sexual dysfunction in 2013. Computerized self-reported measures may facilitate data collection yet were rarely discussed by authors. This meta-review has compiled evidence on generic instruments that can improve the collection of data on sexual function/QoL in research and clinical practice. We also discuss the emerging use of applications, connected wearables and devices that may provide another less invasive avenue for the assessment of sexual function/QoL at the individual and population level.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Sexual function

- Sexual quality of life

- Patient-reported outcomes

- Instruments

- Quality of Life Technologies

- ICT

Introduction

Sex or sexual activity is a core human function. It refers to the way in which people experience or express their sexuality. It encompasses activities done alone (e.g. masturbation) or with another person (intercourse, oral sex, etc.) or people (group sex) [1]. Sexual activity is considered to be an important part of social functioning (also referred to as social health), which is distinct from mental and physical health and seen as an important dimension of quality of life (QoL). Echoing its definition of health, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) has defined sexual health as a “state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity” [2]. The WHO has acknowledged its importance by including an item on sexual activity in its assessment of QoL. The item “how satisfied are you with your sex life?” seeks to capture the desire for, expression of, opportunity for and fulfillment from sex.

These definitions differ somewhat from the assessment of sexual function, which has been defined as “how the body reacts in the different stages of the sexual response cycle”, first described by pioneering researchers Masters and Johnson in the late 1960s [3]. The sexual response cycle was defined as linear stages: (1) excitement, (2) plateau, (3) orgasm, and (4) resolution, all of which are experienced by both men and women [3]. This model of sexual response has since been criticized for its overt focus on the physiological rather than psychological and social components of human sexual response. Subsequent models of human sexual response have aimed to correct these shortcomings. Kaplan incorporated desire into the model [4]. Whipple and Brash-McGreer and later Basson proposed alternative, more complex, models of sexual response in women that were circular rather than linear [5, 6]. Basson’s model specifically recognizes that orgasm may contribute to, but is not necessary for, satisfaction, and emphasizes that relationship factors can affect one’s willingness and ability to participate in sex.

As our understanding of sexual response has evolved, so have accepted diagnostic criteria for sexual dysfunctions (SD) . The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—V, published in May 2013, sought to incorporate newer models of sexual response and to correct, expand, and clarify criteria for diagnoses [7]. Definitions of male sexual dysfunction (MSD) according to the DSM-V include erectile disorder, male hypoactive sexual desire disorder, premature (early) ejaculation, and delayed ejaculation (previously termed male orgasmic disorder). MSD involving pain was removed from the DSM-V. Definitions of female sexual dysfunction (FSD) in the DSM-IV were collapsed in the DSM-V. FSD includes female sexual interest/arousal disorder (previously female hypoactive desire disorder and female arousal disorder), female orgasmic disorder, and genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder (previously dyspareunia and vaginismus). The DSM-V also required that frequency (dysfunction present 75–100% of the time), duration (a minimum of 6 months), and distress be investigated in order to make a diagnosis.

Although epidemiological studies are scarce, SD appear to be prevalent in the general population and varies by sex and age. In a large United States-based survey, conducted in 1992, in adults age 18–59; 43% of women and 31% of men reported experiencing SD over the past 12 months based on the DSM-IV criteria [8]. Disorders of desire/interest, arousal, orgasm and pain appear to be more common in women than in men. The most common complaint in men is premature ejaculation [8]. The causes of SD can be either physical such as common chronic conditions and/or their treatment (e.g., diabetes, heart and vascular disease, hormonal imbalance, alcoholism, etc.) or psychological (e.g., stress, depression).

The high prevalence of SD and its impact on individuals’ QoL prompted the development of pharmacological interventions for addressing these disorders (e.g. erectile dysfunction). It was therefore necessary to develop valid and reliable methods for both diagnosing SD and assessing the impact of experimental interventions on sexual function and QoL. There are a number of direct physiological measures of sexual function used in men and women. For example, erectile function can be diagnosed using a Nocturnal Penile Tumescence (NPT) device [9], Intracavernous Injection of Prostaglandin E1 [10], or the penile/brachial index [11], Doppler studies [12] and sacral evoked potentials. In women, genital blood peak systolic velocity [13], vaginal pH, intravaginal compliance, and genital vibratory perception thresholds are used as direct measures of female sexual function. These direct measures appear to be correlated with indirect measures, specifically hormonal changes within the body, like estrogen, luteinizing hormone, testosterone and prolactin. However, they are useful insofar as for a diagnosis of sexual (dys)function rather than for the assessment of sexual QoL. In addition to direct and indirect objective measures, sexual function and more importantly sexual QoL can also be assessed via standardized inventories or self-administered questionnaires. These vary in their scope (comprehensiveness), measurement properties (evidence of validity, reliability and responsiveness), applicability (e.g., use in women, LGBTI populations) and context (e.g., research versus clinical practice). We hypothesized that although there are numerous instruments, covering sexual function and QoL, not all were sufficiently comprehensive nor were they applicable to all populations.

Furthermore, the use of new technologies have enabled not only the collection of self-reported measures of sexual function and sexual activity in relation to sexual and reproductive health, but may facilitate the collection of indirect measures of sexual activity via applications or personal, miniaturized mobile and wearable devices. The private sector has responded to people’s interest in better understanding not only their reproductive health, for instance with the use of menstruation and/or fertility awareness applications or devices [14], but also, their sexual activity. Mobile phone applications for the assessment of sexual activity run the gamut and allow users to quantify and qualify sexual activity. These applications differ substantially from those aimed at individuals or couples trying to conceive or avoid unwanted pregnancy. Many of these applications still rely on users completing an assessment, reporting and often qualifying their sexual activity, whereas others use the smartphone’s sensors or those of personal devices (Smart watches or rings or sex toys) to log sexual activity. These applications, wearables and devices might offer new opportunities for research and clinical practice. We discuss these opportunities in relation to commonly used methods, e.g., self-administered questionnaires, in this chapter.

Aims

We conducted a review of literature reviews of self-administered assessments of sexual function and QoL to identify viable instruments for the assessment of sexual function in the context of research and clinical practice. We then evaluated their breadth (dimensions assessed), summarized evidence of their psychometric properties and applications (e.g., clinical research/screening) and considered these within the context of emerging technologies.

Methods

We conducted a meta-review of literature reviews focusing on instruments assessing sexual function or sexual QoL. We identified relevant literature reviews from two sources, the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) databaseFootnote 1 and the academic bibliographic databases, specifically Pubmed, PsycInfo and Scopus, using a search algorithm. The former is maintained by COSMIN, an initiative that aims to improve the choice of measurement instruments for research and clinical practice [15]. The following algorithm was used (“sexual satisfaction” OR “sexual quality of life” OR “sexual well-being” OR “sexual function” OR “sexual dysfunction”) AND (“questionnaire” OR “patient-reported outcome” OR “measure” OR “scale”) AND (“review”). The choice of key words, ranging from “quality of sexual life” to “sexual dysfunction”, reflects the lack of consensus regarding definitions of sexual QoL previously evoked. Moreover, in the first search attempts, particularly when using biomedical search engines, it was clear that the terms “sexual dysfunction” and “function” were commonly used to describe the instruments of interest. Including these terms ensured that instruments of interest, that we might have otherwise missed, were identified. We restricted the search fields to titles and abstracts and used search filters to refine the result. We restricted our search to “reviews” or “systematic reviews”, available in English. No restrictions were imposed based on the date of publication and systematic reviews as well as literature reviews were considered. We choose to include non-systematic reviews as well as systematic reviews to ensure that no relevant instruments were omitted. Relevant references were selected based on a review of their title, followed by a review of the abstract by two independent reviewers. In the event of disagreement, the third reviewer provided an opinion. Full texts were then retrieved and screened for inclusion. The results from each database were imported into the Zotero,Footnote 2 free open-source reference management software. Zotero was used to identify and eliminate duplicate references.

Included literature reviews of instruments served to aid in creation of a database of instruments used to assess aspects of sexual function/dysfunction and/or sexual QoL of life in adults. Duplicate instruments were deleted. We then further selected instruments based on the following criteria. We first considered the date of development, preferring to include instruments developed after 1970 to account for changes in sexual and social norms (e.g., women’s liberation and gay rights). We opted to focus this review on instruments, which were generic in nature, meaning that they had not been developed for the evaluation of sexual function/QoL in a specific patient population. The focus of this review was on self-reported measures and therefore physician or researcher administered tools were excluded from this review. We only included instruments which were associated with a peer-reviewed publication. This was re-assessed in case it had not been a requirement for inclusion in the individual reviews. We were interested in the broad assessment of sexual QoL and not merely the physical aspects of sexual function. We chose to exclude instruments, which were too narrowly focused to the physiological dimensions of sexual function (e.g., arousal, performance, orgasm). We did not distinguish between instruments intended for research and those intended for clinical practice at the selection stage; yet we did note whether the selected instrument was intended for research, clinical practice or both when evaluating the selected instruments.

The evaluation of the selected instruments covers both their content and the measurement properties. We wanted to understand whether the existing instruments were sufficiently comprehensive (number and extent of the areas covered), reflecting the complexity of the quality of sexual life. This constitutes an assessment of their content validity, as measurement instruments must adequately reflect construct of interest, in this case sexual QoL. We coded the facets that the instruments purportedly covered according to two broad categories: sexual function and sexual QoL. Items that covered desire and the three physiological stages of sexual response: arousal, plateau (maintaining arousal) and orgasm, and those evaluating the presence of pain were considered to be part of the evaluation of physiologic sexual function. Additional items assessing satisfaction, relational-emotional aspect of sex, self-esteem or body image, and finally, the importance of distress for the individual, were considered to pertain to the subjective, often psychological, dimensions of sexual function, which together with the physiologic dimensions encompass sexual QoL. Furthermore, the anchoring of sexual activity and function with regard to its impact of QoL is important, as this is part of the current criteria for dysfunction. For the evaluation of the psychometric properties of the included instruments, we used the COSMIN taxonomy of measurement properties, based on an international consensus about the relevant properties to be evaluated for any measurement instrument, regardless of its application. We summarized evidence of the instruments’ reliability, validity and responsiveness (10).

Results

Selection of Reviews of Instruments

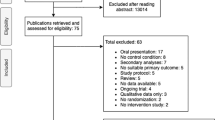

Our search strategy identified 613 references, 133 of which were duplicates, resulting in 480 references. Based on a review of their titles, 411 references were further excluded, as they did not pertain to sexual QoL measures. Sixty-nine abstracts were reviewed independently by two reviewers. There was disagreement regarding the inclusion of 15/69 (22%) references and these were resolved by a third reviewer, ultimately resulting in the exclusion of an additional 58 references, 18 of which were excluded as they pertained to instruments used in specific patient populations. Eleven full texts were retrieved and reviewed and two additional references were excluded because they were not reviews of instruments for the evaluation of sexual QoL. The final number of “generic” reviews included was therefore nine [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24] (Fig. 16.1). The characteristics of these reviews, i.e., date of publication, objectives, populations studied, and number of instruments evaluated, are reported in Table 16.1. Their inclusion criteria, search engines and keywords used are reported in Table 16.2. The reviews were published between 2002 and 2018, five of them were systematic reviews and the majority (7/9) targeted the general population. One review was focused on women and another on homosexual men. Most reviews included only validated instruments. In terms of the quality of the reviews, we noted that certain methodological standards for reviews of instruments were respected: the majority of reviews clearly stated their objective and their predefined inclusion criteria. However, nearly all of the reviews did not explicitly state how they selected references, or whether they complied with a standardized method of instrument evaluation. Reviews tended to focus on instrument validation studies and the instruments themselves. They also were interested in the instruments’ psychometric properties. The definition of sexual QoL appears somewhat nebulous. The number of instruments included varied significantly between reviews. For the sake of accuracy, the information summarized was extracted verbatim from the reviews themselves.

Selection of Instruments for Consideration

A total of 110 instruments were included from the nine reviews retained after the elimination of duplicate records (instruments). Subsequently, six instruments were excluded because of the date of their development (prior to 1970), four were excluded because they did not aim to measure sexual QoL, and two instruments were excluded because they seemed to lack a peer-reviewed validation study. Of the remaining 98 instruments, we retained 34 that were generic measures of sexual QoL and excluded the remainder (N = 64) that were instruments designed for use in a specific patient population. Finally, three of these were excluded because their focus was too narrow, exclusively on sexual function. Thirty-one instruments were ultimately selected for detailed review (Fig. 16.2).

Characteristics of Included Instruments

The characteristics of the instruments included in our study are presented in Table 16.3. The dates of instrument development and/or validation range from 1973 to 2018. Most of the instruments were developed for use in research and clinical practice (77% [24/31]) and approximately half (51%, [16/31]) targeted both males and females or heterosexual partners. The evaluation of the instruments with respect to the dimensions they consider in measuring sexual QoL is reported in Table 16.4. This evaluation allows us to judge the adequacy of an instrument in capturing the complexity of this construct. As expected, instruments often focused on physiological sexual function or phases of the sexual response cycle. On the other hand, psychosocial questions regarding relationships/emotional aspects of sex, body image and self-esteem cultural and gender expectations were only rarely taken into account in the assessment of sexual QoL. The most commonly assessed domains were arousal (N = 19), desire (N = 17), satisfaction and pleasure (N = 17), and frequency (N = 14). The most comprehensive instrument appears to be the Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory (DSFI), covering nine dimensions of sexual QoL. The DSFI was one of the few instruments to assess distress, relationship issues, fantasies and cultural and gender roles. The importance of sexual activity for the individual was only assessed in six of the 31 instruments reviewed. Of note, we found that the majority were not developed with the involvement of lay individuals or those coping with SD.

Discussion

Sexual activity is an important part of social functioning and consequently QoL. Over 100 self-administered instruments have been developed to respond to an interest in assessing sexual function/dysfunction and QoL in the context of research and clinical practice. These instruments nevertheless vary in their purpose and scope, making selecting the appropriate measurement tool potentially challenging for those wishing to assess sexual activity, function and QoL. This meta-review aimed to provide an up-to-date overview of generic rather than disease-specific instruments that can be used in men and/or women. Thirty-one self-reported measures of sexual QoL with documentation of their psychometric properties were considered. Only three, however, were developed after 2013, the year the DSM-V revised the definition of male and female SD. Furthermore, there seems to be no consensus as to what constitutes the key dimensions of sexual QoL beyond the phases in the sexual response cycle. Nevertheless, our meta-review highlights that there has been an effort to address the specific needs of women, evidenced by the 12 instruments included which were for use in women [21].

There is a notable lack of instruments designed for use in homosexuals. Only one of these reviews sought to explore the availability of instruments in a specific population: gay men. McDonagh’s systematic review from 2014 comprised only seven instruments that were potentially viable for use in this specific population. She pointed to a number of shortcomings, specifically hetero-normative or heterosexist language [22], concluding that there was currently no psychometrically sound measure of male sexual function that can be used in gay men. The lack of involvement of sexual minorities in the development of these instruments may be at fault.

The issue of patient/individual involvement in instrument development was also raised by Arrington et al. [18] in their review from 2004. They questioned whether available instruments would be more comprehensive had items been generated using qualitative research in a diverse group of patients either representative of the general population or dealing with SD. The study population often selected for instrument validation studies is also a concern as many scales appear to have been validated in patients with SD, rather than community samples. This raises concerns about their ability to detect SD in the general population.

There is also limited evidence of instruments’ responsiveness or their ability to detect change over time. Evidence of responsiveness had only been documented in seven of the 31 instruments considered. Users should be wary of this limitation as they consider these tools for use in research or clinical practice.

Surprisingly, none of the reviews addressed the issue of the electronic collection of sexual function/QoL in spite of the fact that the practicality of administering, mostly face-to-face or self-administered paper-and-pencil, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) has been documented as a major barrier to their use, particularly in clinical practice. Paper-based approaches require that a physician and/or other staff administer the questionnaire during the consultation and enter and/or analyze data manually, requiring resources to collect, analyze and utilize PROs data [54]. Computerized PRO assessments have become common in settings where PROs have been widely adopted, offering a number of advantages over pencil-and-paper assessments. For example, applying compulsory items and pre-specifying acceptable ranges or values can improve data completeness and quality. Complex skip patterns can be programmed or Computer Adaptive Testing (CAT) methods applied to ease administration [55]. Immediate data capture also reduces the burden and/or costs associated with data entry [56]. Furthermore, from a methodological point of view, there is strong evidence to suggest that electronic and paper-and-pencil administration methods are equivalent [57].

New technologies are yet another means of assessing sexual activity. We see the emergence of technologies making use of both active, memory-based data capture methods, which are subjective and socially acceptable, and passive, technology-based methods—via wearables and personal devices—which are sensory-based, momentary, non-judgmental and context-rich. Sexual activity assessment applications (also referred to as “sex trackers”) take an alternative approach, seeking to help individuals improve the quality of their sex lives via various means such as educational content including erotica, personalized advice, forums, data visualization, and automated statistics (…). Wac has qualified technologies such as these as “Quality of Life Technologies” (QoLT) or any technology designed for the assessment or improvement of individuals’ QoL. These “leverage miniaturized computing, storage, and communication sensor- and actuator-based, context-rich technologies that can be embedded within various personal devices” [58]. Some technologies seek to appeal to all, whereas others focus specifically on features that appeal to sexual minorities or are deliberately gendered. Applications like CoralFootnote 3 (an intimacy app that relies on education), RosyFootnote 4 (a platform offering women a holistic approach to sexual health and wellness, offering education, self-discovery and community), Sex LifeFootnote 5 (a sex tracker, sex diary and sex calendar) are novel as their core functionalities are not geared towards sexual activity for fertility or the prevention of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Unsurprisingly, most of these applications still rely on memory-based approaches to capture users’ data, differing from now commonplace applications designed to assess and improve physical fitness. Nevertheless, they offer features that seek to maintain, prevent, or enhance sexual QoL, fitting with the aims of QoLT . Many of these application and service providers have already begun to collaborate with universities and researchers, often establishing cohorts of users and generating a wealth of real-world data.

Other mobile applications are hybrids, pairing sexual activity assessment with the promotion of sexual health (e.g., STI prevention or testing). For example, applications like BiemFootnote 6 or SafelyFootnote 7 focus on convenience. The former offers telemedicine and at home or laboratory testing. The latter connects users with a network of laboratories and allows them to receive their results electronically. They have also incorporated interactive features; both allowing users to make their data available to partners or potential partners securely and privately and the functionality “Biem Connect” allows sexual partners to be notified anonymously if one of their partners tests positive for an STI. NiceFootnote 8 is a combination of a sexual activity assessment application that allows for some data on STIs to be collected. Data entered through these applications can be synched with the Apple HealthKit,Footnote 9 which allows users to record their reproductive health data, including the occurrence of sexual activity.

The use of wearables (e.g. Smartwatches, rings) and personal devices (e.g. sex toys) to measure sexual activity appears to be possible as they work by measuring whole-body motion (accelerometer), heart rate (photo plethysmography), body temperature, and respiration rate. The use of these devices, such as the Oura RingFootnote 10 or MyMotiv RingFootnote 11 (personal health or fitness trackers worn as rings) have been used to successfully generate detailed data corresponding to different parts of the sexual response cycle. However, most still require users to qualify increases in peaks and valleys in physiological data captured by wearable devices as sexual activity. Although, to date, the use of fitness trackers and Smartwatches to capture this highly sensitive data does not seem to be the approach most favored by QoLT developers, there is evidence, mostly from popular culture, that quantified self-ers are embracing these new technologies. They are willing to monitor their own behaviors, even their sex lives, to gain a greater understanding of their bodies, in the vein of “knowing thyself” and perhaps even in an attempt to improve their (sexual) QoL [59]. Connected personal devices offer yet another avenue for passive data collection related to sexual function or activity. For example, users of biofeedback vibrators like the LionessFootnote 12 can, in addition to traditional functionalities, visualize their precision sensor-generated data via an application and participate in medical and academic research by opting to share their de-identified data. Another connected wearable is the Lovely 2.0,Footnote 13 a connected penis ring, which, when worn during sex learns about your “style” of having sex and provides personalized advice via a dedicated application. Some research is currently ongoing to validate these sex toys as viable research tools. There is a need to understand how data generated from applications, wearables and connected devices correlates with direct and indirect measures of sexual function and self-reported measures seeking to capture sexual QoL as a broader construct.

As it is important to get information from the best source when standardizing the assessment of sexual activity, function and QoL, we proposed the following sources of information for each of the different dimensions according to Mayo et al. taxonomy [60] (Table 16.5). These include self-reports like patient-reported outcomes (PROs), collected via the proposed self-administered instruments, which clearly vary in both length and scope and Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) techniques, in which individuals report states close to the time they experience them, as well as other reports like observer/proxy-reported outcomes (ObsRO/ProxyRO) and Peer-Ceived Momentary Assessments Methods (PeerMA) [61]. Both ObsRO/ProxyRO and PeerMA would rely on an “other”, likely to be an intimate partner rather than a friend in the case of sexual activity reporting on an individual’s perceived state and behaviors. The former doing this at fixed time points and the latter on a momentary basis, similar to the collection of EMAs. These could be useful insofar as externally observable behaviors and states are concerned, e.g. perceived desire, arousal, plateau, and orgasm as well as the frequency of sexual activity with a partner. Finally, technology-reported outcomes (TechROs) which could be collected via wearables, Smartphone behavioral metrics, or connected devices could be used for many of the domains important to the assessment of sexual function/QoL, namely if whole-body motion and physiological parameters could be co-calibrated with valid direct, indirect, or self-reported measures of sexual function/QoL, We have summarized some options for assessing and measuring different domains below in Table 16.5.

Conclusions

There are a number of generic self-reported instruments that can ease the collection of data on sexual function and QoL in both research and clinical practice. The emerging use of sexual activity assessment applications, wearables and personal devices, may also provide another less invasive avenue for the collection of sexual activity data. There is nevertheless a need to understand the measurement properties of these novel means of data generation as well as users’ willingness to submit or share their highly personal data with researchers or providers in order to facilitate their adoption in research and clinical practice. There is still a long way to go if we wish to exploit the full potential of QoLT for sexual health and QoL.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

- 12.

- 13.

References

Gebhard PH. Human sexual activity Encyclopædia Britannica 2019 June, 26 2020.

World Health Organization, D.o.R.H.a.R., Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28–31 January 2002, Geneva, WHO, Editor; 2006: Geneva.

Masters W, Johnson V. Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little Brown; 1966.

Kaplan H, Disorders of sexual desire and other new concepts and techniques in sex therapy. New York. New York: Brunner/Hazel Publications; 1979.

Basson R. Female sexual response: the role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(2):350–3.

Whipple B, Brash-McGreer K. Management of female sexual dysfunction. In: Sipski M, Alexander C, editors. Sexual function in people with disability and chronic illness. A health professional’s guide. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1997.

Sungur MZ, Gündüz A. A comparison of DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 definitions for sexual dysfunctions: critiques and challenges. J Sex Med. 2014;11(2):364–73.

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537–44.

Nocturnal penile tumescence study. In: Male sexual dysfunction; 2017. p. 129–32.

Linet OI, Neff LL. Intracavernous prostaglandin E1 in erectile dysfunction. Clin Investig. 1994;72(2):139–49.

Scott JR, Liu D, Mathes DW. Patient-reported outcomes and sexual function in vaginal reconstruction: a 17-year review, survey, and review of the literature. Ann Plastic Surg. 2010;64(3):311–4.

Varela CG, et al. Penile Doppler ultrasound for erectile dysfunction: technique and interpretation. Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214(5):1112–21.

Berman JR, et al. Clinical evaluation of female sexual function: effects of age and estrogen status on subjective and physiologic sexual responses. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11(Suppl 1):S31–8.

Symul L, et al. Assessment of menstrual health status and evolution through mobile apps for fertility awareness. npj Digital Med. 2019;2(1):64.

Mokkink LB, et al. The COnsensus-based standards for the selection of health measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz J Phys Ther. 2016;20(2):105–13.

Daker-White G. Reliable and valid self-report outcome measures in sexual (Dys)function: a systematic review. Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31(2):197–209.

Meston CM, Derogatis LR. Validated instruments for assessing female sexual function. J Sex Marital Therapy. 2002;28(Suppl. 1):155–64.

Arrington R, Cofrancesco J, Wu AW. Questionnaires to measure sexual quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(10):1643–58.

Corona G, Jannini EA, Maggi M. Inventories for male and female sexual dysfunctions. Int J Impotence Res. 2006;18(3):236–50.

DeRogatis LR. Assessment of sexual function/dysfunction via patient reported outcomes. Int J Impotence Res. 2008;20(1):35–44.

Giraldi A, et al. Questionnaires for assessment of female sexual dysfunction: a review and proposal for a standardized screener. J Sex Med. 2011;8(10):2681–706.

McDonagh LK, et al. A systematic review of sexual dysfunction measures for gay men: how do current measures measure up? J Homosex. 2014;61(6):781–816.

Santos-Iglesias P, Mohamed B, Walker LM. A systematic review of sexual distress measures. J Sex Med. 2018;15(5):625–44.

Cartagena-Ramos D, et al. Systematic review of the psychometric properties of instruments to measure sexual desire. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):109.

Patterson DG, O’Gorman EC. The SOMA—a questionnaire measure of sexual anxiety. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;149(1):63–7.

LoPiccolo J, S JC. The sexual interaction inventory: a new instrument for assessment of sexual dysfunction. In: LoPiccolo J, L L, editors. Handbook of sex therapy. Perspectives in sexuality (Behavior, research, and therapy). Boston: Springer; 1978.

Harbison JJ, et al. A questionnaire measure of sexual interest. Arch Sex Behav. 1974;3(4):357–66.

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The DSFI: a multidimensional measure of sexual functioning. J Sex Marital Ther. 1979;5(3):244–81.

Andersen BL, et al. A psychometric analysis of the sexual arousability index. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(1):123–30.

Mark KP, et al. A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. J Sex Res. 2014;51(2):159–69.

Rust J, Golombok S. The GRISS: a psychometric instrument for the assessment of sexual dysfunction. Arch Sex Behav. 1986;15(2):157–65.

Libman E, et al. Jewish General Hospital sexual self monitoring form. In: Davis CM, et al., editors. Handbook of sexuality related measures. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998. p. 272–4.

Geisser ME, et al. Reliability and validity of the Florida sexual history questionnaire. J Clin Psychol. 1991;47(4):519–28.

Kaplan L, Harder DW. The sexual desire conflict scale for women: construction, internal consistency, and two initial validity tests. Psychol Rep. 1991;68(3 Pt 2):1275–82.

Taylor JF, Rosen RC, Leiblum SR. Self-report assessment of female sexual function: psychometric evaluation of the brief index of sexual functioning for women. Arch Sex Behav. 1994;23(6):627–43.

Snell WE, Fisher TD, Walters AS. The multidimensional sexuality questionnaire: an objective self-report measure of psychological tendencies associated with human sexuality. Ann Sex Res. 1993;6(1):27–55.

Marita PM. Sexual function scale: history and current factors. In: Terri D, et al., editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. New York: Routledge; 1988.

O’Leary MP, et al. A brief male sexual function inventory for urology. Urology. 1995;46(5):697–706.

Thirlaway K, Fallowfield L, Cuzick J. The sexual activity questionnaire: a measure of women’s sexual functioning. Qual Life Res. 1996;5(1):81–90.

Spector IP, Carey MP, Steinberg L. The sexual desire inventory: development, factor structure, and evidence of reliability. J Sex Marital Ther. 1996;22(3):175–90.

Creti L, et al. “Global sexual functioning:” a single summary score for Nowinksi and LoPiccolo’s sexual history form (SHF). In: Davis CM, et al., editors. Handbook of sexuality-related measures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

McGahuey CA, et al. The Arizona sexual experience scale (ASEX): reliability and validity. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(1):25–40.

Rosen R, et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):191–208.

Dennerstein L, Lehert P, Dudley E. Short scale to measure female sexuality: adapted from McCoy female sexuality questionnaire. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27(4):339–51.

Derogatis LR, et al. The female sexual distress scale (FSDS): initial validation of a standardized scale for assessment of sexually related personal distress in women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(4):317–30.

Quirk FH, et al. Development of a sexual function questionnaire for clinical trials of female sexual dysfunction. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(3):277–89.

Meston C, Trapnell P. Development and validation of a five-factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale for women: the sexual satisfaction scale for women (SSS-W). J Sex Med. 2005;2(1):66–81.

Heinemann LA, et al. Scale for quality of sexual function (QSF) as an outcome measure for both genders? J Sex Med. 2005;2(1):82–95.

Toledano R, Pfaus J. Original research—outcomes assessment: the sexual arousal and desire inventory (SADI): a multidimensional scale to assess subjective sexual arousal and desire. J Sex Med. 2006;3(5):853–77.

McCall K, Meston C. Cues resulting in desire for sexual activity in women. J Sex Med. 2006;3(5):838–52.

DeRogatis L, et al. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sexual Med. 2008;5(2):357–64.

Goldhammer DL, McCabe MP. Development and psychometric properties of the female sexual desire questionnaire (FSDQ). J Sexual Med. 2011;8(9):2512–21.

Santos-Iglesias P, et al. Psychometric validation of the female sexual distress scale in male samples. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(6):1733–43.

Feinstein AR. Benefits and obstacles for development of health status assessment measures in clinical settings. Med Care. 1992;30(5 Suppl):Ms50-6.

Sands WA, Waters BK, McBride JR, editors. Computerized adaptive testing: from inquiry to operation, vol. xvii. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. p. 292.

Jones JB, Snyder CF, Wu AW. Issues in the design of Internet-based systems for collecting patient-reported outcomes. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(8):1407–17.

Gwaltney CJ, Shields AL, Shiffman S. Equivalence of electronic and paper-and-pencil administration of patient-reported outcome measures: a meta-analytic review. Value Health. 2008;11(2):322–33.

Wac K. Quality of life technologies. In: Gellman M, editor. Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. New York: Springer; 2019. p. 1–2.

Wac K. From quantified self to quality of life. In: Rivas H, Wac K, editors. Digital health: scaling healthcare to the world. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 83–108.

Mayo NE, et al. Montreal Accord on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) use series – Paper 2: terminology proposed to measure what matters in health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:119–24.

Berrocal A, et al. Complementing human behavior assessment by leveraging personal ubiquitous devices and social links: an evaluation of the peer-ceived momentary assessment method. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(8):e15947.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Camille Etcheverry, Cecilia Dumar and Camille Berduras for their assistance in conducting this review and the editors for their helpful comments.

Funding

This research was conducted during Diana Barger’s post-doctoral research fellowship (2020–2022), funded by the Agence nationale de recherche sur le SIDA et les hépatites (ANRS), at the University of Bordeaux/Inserm Bordeaux Population Health Research Centre (U 1219).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barger, D. (2022). Sexual Function and Quality of Life: Assessing Existing Tools and Considerations for New Technologies. In: Wac, K., Wulfovich, S. (eds) Quantifying Quality of Life. Health Informatics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94212-0_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94212-0_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94211-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94212-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)