Abstract

This chapter suggests that humankind needs to reconsider its relationship with the planet’s amazing miracle: Life. Shifts in mindsets need to reflect this emerging new view of reality. COVID-19 as a global pandemic has alerted many people not only to the need to realign humankind’s relationship with nature, but also highlighted the global interconnectedness and the vulnerability of people. The increasing concern for the future of humanity and our life-support system needs reflections about the underlying view of reality that informs approaches to transformations. If humanity wants to rise up to collective stewardship towards stabilizing the trajectories of our planet, transformation actors need to become humble partners of life’s potential to renew and replenish. The chapter introduces the concept of systems aliveness as a guiding compass for transformative change. It emphasizes that understanding what gives life to systems needs to be at the centre of emerging transformation literacy. Drawing from multiple, interdisciplinary sources of the systems aliveness approach offers an avenue to reorientate transformation efforts around six generic principles. Using these principles as a lens to designing transformation initiatives and translating them into a stewardship architecture provides creative pathways for the long journey to regenerative civilizations.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Systems aliveness

- Stewarding wellbeing

- Healthy planet

- Collective stewardship

- Transformation literacy

- Resilience

- Interconnectedness

- Regeneration

1 Introduction: Life as a Reference Point

The current state of the world suggests that, as humankind, we need to reconsider our relationship with the planet’s amazing miracle: Life. So far, with all explorative endeavours to Mars, according to our current scientific knowledge, our’s is the only home in the universe that thrives on an ever-more complex dynamic of Life. It creates, fosters and regenerates Life in a perpetuating cycle of living and dying. Life is within us and around us, we sense it, feel it, know about it and mourn, if we see it disappearing. This mourning we all have experienced when a loved-one passes away, a relationship ends, or societies move into turmoil. But the mourning about losses at planetary scale, which some indigenous traditional cultures have predicted since long, has now reached many more people. If glaciers melt that are climate stabilizers and offer water security; if permafrost melts and releases carbon dioxide, aggravating in the atmosphere; or if forests, even rainforests are burning and extreme weather events kill people, the mourning is beginning to reach many more people’s hearts. The heart’s connection to these tremendous losses is a driver of the sense of urgency we need in order to halt the downward-spiralling trajectories of our future. Reconnecting the heart with our planet’s miracle engenders the humility which we need in order to reshape our relationship with planetary health and human wellbeing.

It is increasingly clear that the coming 15–20 years will have a decisive impact on the conditions of life on Earth, more than in any period before (Steffen, 2018). COVID-19 as a global pandemic has alerted many people not only to the need to realign humankind’s relationship with nature, but also highlighted the global interconnectedness and the vulnerability of people.Footnote 1 Awareness is rising about the urgency of dealing with climate change as the most palpable impact of human behaviour on the planetary system. Concepts such as the planetary boundaries (Rockström, 2009) have alerted many people, not only academics, to the need to turn the increasing concern for the future of humanity and our life-support system into action. In the year 2021, with a pandemic that, globally, is not yet over, and in a planetary emergency that shows how humans negatively impact on planetary life-support systems, reconnecting with Life is not only an intuitive urge, but a rational decision. It is scientifically substantiated and requires political, organizational and individual decision-making, everywhere and at all levels of the global society. Redefining what it means to be human in this world requires heart and mind. It requires memory, because with all achievements of modernity as well as human and technological advancements, the last few centuries have infiltrated us with the illusion of being separate from nature. We are not. The globally penetrating human consciousness development that created this notion of separateness from nature as well as the prioritization of masculine traits in societal development has a long history, but its accelerated impact on human behaviour can most profoundly be traced back to a scientific revolution (Merchant, 1980). It took place in Europe around 1600 onwards with, among others, the most influential protagonists such as Francis Bacon, who urged that nature needed to be conquered, penetrated and controlled; or Rene Descartes, who promoted a rational-analytic approach that denied nature living, sentient, interconnected qualities (Berman, 1981; Conner, 2005). This can be seen as a paradigm shift that happened in European human mindsets and subsequently generated both science and societies which achieved enormous technological advancements built on the notion of human separateness from nature. Increasingly, and today dangerously, this created a major threat to the conditions that support life and in particular, human life on Earth (Hawken, 2007; Raskin, 2016). But there is another paradigm shift underway that suggests to re-affirm human relationship with Life. COVID-19 reaffirms that we need to admit that our future is ‘biological, not digital’ (Nair, 2021). Technological advancements and also digitalization can be a tremendous help in regenerating and safeguarding our planetary life-support system. But unless we get our collective purpose clear, that is to advance a future in which wellbeing on a healthy planet is the centre of attention, and steward technological advancements towards this purpose, it will haunt us (WBGU, 2019). Only a few years ago, the many interdependent sustainability issues such as biodiversity loss, water scarcity, deforestation, ocean pollution, topsoil erosion, and growing inequality, among many others, were often seen as intractable or ‘wicked problems’ (Churchman, 1967; Rittel & Webber, 1973; Waddell et al., 2015) as if they had occurred without traceable cause, and as if they only called for political, technical and administrative solutions. While all such approaches have their purpose and validity, they tend to stay within a frame of thinking that can be identified as a worldview of disconnection from the underlying systemic interdependence of the world, and a disconnection from our intrinsic relationship with Life (Capra & Luisi, 2014; Korten, 2007; Yamash’ta et al., 2018; Wahl, 2016; Weber, 2016). This disconnected worldview is guided by a mechanistic conception of problems that need to be fixed as if a machine needed repair. It seduces us into the illusion of regaining control, ‘fighting’ climate change, ‘combatting’ the loss of species, and solving the damages of extractive industries by renewable energy technology only. None of these approaches is entirely wrong, the narrative of emergency fuels action for important approaches and behavioural changes that may work and are a glimpse into a more responsible future, such as greening the economy, switching to renewable energies, re-establishing wilderness zones, or introducing tax systems that not only reflect true and normally externalized production costs, but also redistribute wealth. However, as long as the understanding of the world does not shift from a machine-like controllable object to a complex interconnected alive organism, such approaches may fall short of their potential. What is needed is asking more fundamental questions of what the purpose of a responsible human endeavour should be on a planet that is in danger, and which is at the same time the support system that carries all forms of Life—also the human form of life. This chapter argues that a novel understanding of ‘what gives Life to systems’—in human (and natural) systems—needs to underpin the design of future economic and societal systems that model wellbeing on a healthy planet and the development of pathways towards transformative change.

2 Partnering with Life

What if our task as humankind is to develop (or regain) the capability to recognize, foster, regenerate and maintain the conditions for Life to thrive in the complex holarchy of systems that we are embedded in? Then, the cornerstone of transformation literacy is to steward (not steer and not control) multiple systems towards aliveness. The question ‘what gives Life to systems?’ will become the central question in partnering with Life. The results will never be perfect, and need to always be open for negotiation and new learning. But stewarding many small interlinked systems at the same time in many different places in the world will move our planet Earth out of the danger zone into the ‘safe operating space’ so many scientists are suggesting (Otto et al., 2020). A mindset shift towards reconnection with Life, both intuitively and rationally, is like a North Star or Southern Cross: a guiding force for working towards a world that works for 100% of humanity and our planetary home. This will happen differently in different contexts, but serve the overall integrity of Life. The question of what makes systems alive will become the guiding question for transformation literacy. Systems aliveness is here defined as the capability of small and larger systems to gain resilience, regenerate and maintain their vitality in mutual consistency with other systems (Kuenkel, 2019). Yet, the capability of systems—small or large—to develop a sufficient degree of vitality and resilience is not an end state to be reached, but a continuous process of learning and adaptation. It is a relational constellation of conditions that we can perceive and consciously influence.

In this context, it is important to remember the insight from the Santiago Theory of Cognition that the process of cognition is a constituting process of life (Capra & Luisi, 2014; Maturana & Varela, 1991). The ability to recognize patterns that enhance aliveness can be lifted into at least partial consciousness and this means that a discourse about aliveness patterns and their influence on transformations is possible, both individually and collectively. As Duane Elgin emphasizes: ‘Whether we regard the universe as dead or alive at its foundations has enormous consequences for our future, both individually and collectively’ (Elgin, 2009, position 367 kindle version). Such a discourse can enhance the understanding about both the manifold patterns that enhance a shared liveable future of humankind. Becoming aware of the patterned occurrence of systems aliveness is a cornerstone for recognizing patterns of behaviour, social interaction and socio-ecological-economic structures that enhance or prevent wellbeing on a healthy planet (Kelso, 1997; McKenzie et al., 2009).

Understanding the principles and patterns behind systems aliveness will engender us to ask how best we can steward aliveness in the multiple systems we influence and how we can become a guiding force for approaching the behavioural transformations we so deeply need. The collective capacity to create the transformative change across societal sectors, institutions and nations, will be enhanced by a narrative of fostering systems aliveness through recognizing, regenerating, maintaining and safeguarding life-support systems in all their variations. Subsequently, actors who are now driven by narratives of threat and fear could become conscious stewards of aliveness in socio-ecological-economic systems. Yet, have we scientifically and practically understood, what gives Life to systems and how, in our attempts to steward transformations towards a regenerative civilization, we can foster and support life? Not yet fully! However, there are many knowledge streams that open new pathways of thinking that not only challenge the outdated European-induced view of the world, but provide openings for new mindsets. In this chapter, I will show how the systems aliveness approach cannot only inspire mindset shifts, but become the basis for designing transformative pathways and evaluating systems that may better match a regenerative future.

After looking at the emerging trend of Life as reference point for understanding the world and transformative collective action, I will explore the conceptual foundations of the systems aliveness approach. At its core are six principles that govern socio-ecological systems in support of systems aliveness. I will describe the principles in more detail based on transdisciplinary systems research and show how these principles can be translated into various different aspects of designing transformative change. I will conclude with suggestions on how the shift in focus towards Life as a reference point, enhances the stewardship task as the essence of transformation literacy and how this empowers change-makers to shift from navigating emergencies to stewarding systems aliveness.

3 An Emerging Trend to Refocus on Purpose

With the lens of Life as a reference point for transformative change, one notices that there is a growing body of scientific literature, monographs, policy papers, activists reports or mission statements for transformation initiatives that build momentum for a reorientation of purposeful and scientifically grounded collective action towards systems aliveness. Narratives about reorientating our relationship with Life have been emerging since the end of the last century (Berman, 1980; Capra, 1995; Deluca, 2016; Elgin, 2009; Eisler, 1988; Elworthy, 2014; Harding, 2006; Hawken, 1993; Korten, 2007; Kuenkel, 2019; Mies & Shiva, 1993; Yamash’ta et al., 2018). They are slowly taking root in policy-making, in community development and in the field of economics. Examples for this trend are manifold, of which a few should be mentioned in an illustrative way. The president of the EU commission adopted the term ‘vitality’ as a new narrative for the future of Europe in her State of the Union Address in September 2020.Footnote 2 The Global Commons Alliance, a cooperation of more than 50 organizations in policy, science, advocacy and business refers in their aims to the ‘health of vital systems’ for ‘people and planet to thrive’.Footnote 3 Many new economic approaches that aim to reverse the focus on unlimited growth and to realign economic activities around values, make special reference to a redefined purpose such as ‘an economy in service to life’ (Lovins et al., 2018), a wellbeing economy (Fioramonti, 2017) or regenerative economies which focus on systemic health, self-renewal and the vitality of socio-economic systems (Fullerton, 2015). Korten’s (2007) proposed narrative for a living economy suggests that we need to refocus on a partnership with nature with the aim of maintaining the conditions that are essential for life to thrive. Not surprisingly this has also entered the domain of research and practice of what is considered human progress and how to measure it (Hoekstra, 2020). Among many other attempts to measure systems aliveness is the Quality of Development Index (QDI) (Raskin et al., 2010, p. 2631) which rates a set of indicators such as wellbeing in human lives, combined with the strength of communities, or the resilience of the biosphere. Similarly, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2015) has developed a ‘Better-Life-Index’ with indicators that in combination rate individual wellbeing in relation to societal conditions Systems aliveness is also at the centre of initiatives such as the de-growth movement, which aims to ‘prioritize social and ecological wellbeing’ and ensure a ‘good life for all within planetary boundaries’.Footnote 4 In connection with the planetary boundaries, academic research that refers to the urgency of more conscious and effective sustainability transformations has introduced the idea of Earth stewarding as a way of safeguarding the ‘life-support system’ (Steffen, 2018; Otto et al., 2020)—symbolizing the multiple and relational conditions required for the overall health of our planetary system. Fundamentally, also the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can be interpreted as an attempt to shift dysfunctional patterns of activity in human and socio-ecological systems towards more functional, more flourishing—or alive—patterns that work better for all, including living beings other than humans (Kuenkel, 2019; Waddock & Kuenkel, 2019).

The current emerging communicative trend around systems vitality or aliveness has scientific and philosophical roots that take us back not only to the work of scholars that have advanced such a worldview in the last century. Apart from its origin in many indigenous wisdom communities around the world that see human beings as partners and servants of ecological harmony, a life-enhancing worldview was also widely recognized during exactly the times that created the foundation for a rational and rather reductionist scientific revolution. In the eighteenth century Alexander von Humboldt, among many other of his contemporary research fellows saw human beings unseparated from nature and in obligation to its safeguarding and care. Humboldt also urged his readers to notice the patterned connection between the destruction or exploitation of people in slavery and oppression with destruction of nature. He saw evolution as a non-hierarchical self-organized complexity—a republic of freedom, and with reference to Schelling and Goethe, as a living organism functioning in constant mutual relationality (Wulf, 2016). Yet with industrialization rising and a biased interpretation of the works of Darwin (Weizsäcker & Wijkman, 2018), the separation of nature from the human endeavour became the more popular worldview, accompanied by the many variations of machine metaphors that not only reduced the non-human world to ‘resources’ to be exploited, but also people to ‘labour’ and ‘human capital’, and ‘life’ to something to be controlled and managed. Although not mainstreamed, different worldviews emerged with the advent of systems theory, quantum physics and semio-biology in the beginning of the twentieth century (Capra & Luisi, 2014; Weber, 2016).

An important insight from systems theory was that the properties of living systems cannot be reduced to those of their smaller parts. Moreover, living systems were seen as relational and arising from the pattern of relationships between the parts. This led to the confirmation of insights that were actually much older: that every organism, animal, plant, microorganism, or human being, but also landscapes, cities and communities must be seen as integrated wholes in constant communication and interconnectedness (Macy & Brown, 2014; Sahtouris, 2000) For an understanding of the relational nature of a system’s aliveness or vitality, the concept of patterns is crucial. If the nature of reality and evolution is viewed as consisting of interconnected, co-evolutionary and purposeful patterns that generate aliveness (or the opposite) the question arises, which patterns are conducive to both individual and overall systems aliveness and which not (Alexander, 2002; Finidori et al., 2015; Kuenkel, 2019; Weber, 2016). The process of pattern cognition has been described as a constituting process of all life by systems thinkers (Capra & Mattei, 2015; Maturana & Varela, 1987). Lifting this process into consciousness and making it accessible to decision-makers and change agents would engender a collective discourse about life-enhancing patterns. Becoming aware of the patterned occurrence of life in evolutionary processes can be seen as a cornerstone for recognizing patterns of behaviour, social interaction and socio-ecological-economic structures that are either conducive or detrimental for systems aliveness. Developing new narratives and shared languages around systems aliveness enables collectives of actors to more consciously steward transformative change.

A deeper perspective both scientific and experiential on the process of recognition of conditions that further or hinder patterns of aliveness in smaller and larger systems opens pathways to new ways of designing and enacting transformative change. What is needed, is an accessible understanding of the foundational principles of ‘what gives life’ to systems and the ability to translate these principles into more life-enhancing transformative change. This is captured in the systems aliveness approach explored here.

4 The Systems Aliveness Approach

One of the roots of the conceptual foundation for the principles of systems aliveness is Alexander’s (1979) approach to the ‘quality of life’ in art and architectural forms as he explains it in his work on pattern language and the nature of order. His breakthrough discovery that has found resonance not only in architecture but also in software development (Gabriel, 1996), was the insight that ordered space has an effect on the degree of ‘life’ in that space, which always extends from the degree of wholeness as a complexity in diversity and interaction of a given space (Alexander, 2004, 2005). Hence, he urges us to understand the patterns and conditions of ordering space and suggests that we have a responsibility to create life-enhancing spaces, not the opposite. Before Alexander, the activist and urbanist Jane Jacobs (1961) wrote about ‘The Death and Life of Cities' portraying a view, in which, again, space in interaction constitutes aliveness of those who live, work, operate or enter the space. She also reminded us of the similarities between ecology and economy, when she suggested that, in their combination, they should be called ‘bionomy’ in the sense of ‘life management’, because exactly this should be their integrated purpose (Jacobs, 2000). It is just that in the common understanding of economics the idea of ‘life’ in all its complex dimensions has been reduced to the ‘free market’ doctrine that so vividly underpins the neoliberal economic framework which, undoubtedly, has contributed to the current endangered state of the planet (Lovins et al., 2018). Only recently, the notion of ‘live-enhancement’ is also entering the discourse around new forms of doing business (WBCSD, 2020).

Another novel approach to understanding systems aliveness comes from biology. The semi-biologist Andreas Weber (2016) concludes from explorations into biology and biosemiotics that ‘life’ is always intentional, not only human life. It seeks to go on, expand and regenerate again and again. In his view, human beings share this underlying urge for aliveness and yet also are gifted with reflective consciousness so that they not only experience aliveness, but can also understand the process of its emergence and intervene in it. In order for Life to thrive in global and local contextuality, value systems that underpin life-enhancing action need to be anchored in the living network of constant human/ecology interaction (Weber, 2013). System aliveness, then, is not an end-state to be reached, but a transitory moment that is based on iterative learning in a living network fashion, in constant reciprocal interactions, and continuous mutual transformations. It is a never-ending negotiation between what is good for the whole as well as for the individual, a continuous negotiation of power balances and interests pursued. Systems aliveness is not false harmony, but a deep accountability to co-evolutionary pathways that honour the integrity of the planet and of people. In regenerative civilizations with embedded regenerative economies working towards an alive and ecologically intact planet with a thriving humanity, the notion of systems aliveness would not only be deeply embedded in the societal value system, but also anchored in the way institutions, companies and citizens act. In such a future, companies would be purpose-driven in their contribution to the common good (Hollensbe et al., 2014). Licenses to operate would require transparency about how products and services further or diminish patterns of aliveness. Reporting against compliance-driven metrics as, e.g. water or carbon footprints would refer to overall and contextually agreed systems aliveness indicators. Governments would foster containment of geographical identities and would support collective performance in terms of local and national systems aliveness as well as a country’s contribution to planetary health. Politicians would be judged and elected according to their capability to steward systems towards balanced vitality in a process of co-negotiation and co-creation with their citizens, both inspired and constraint by globally guiding criteria of planetary aliveness. Civil society organizations would broaden their mandate as guardians of ecological and social resilience, and expand their pioneering role in advocating for and monitoring of societal vitality. Governance systems at global, regional, national and local level would include multiple stakeholders to ensure continuous learning and would arise for different issues. Multi-stakeholder collaboration would increase as needed in order to maintain or co-create patterns of aliveness in alliances, networks and partnerships. Educational systems would teach the narrative and foundation for seeing the world as an interconnected whole and would equip students with diverse competencies to further wellbeing on a healthy planet. A shift in consciousness towards recognizing, regenerating and safeguarding systems aliveness in its many contextualized variations would serve humankind individually and as a collective, and also serve the planet as a whole. But in order to take root, it needs to be accompanied by practical approaches and translated into the way the current institutions function.

This is the purpose of the systems aliveness approach. Conceptually grounded in multidisciplinary research into the work of many scholarsFootnote 5 that substantiated the need for a reorientation towards Life, the approach shows that stewarding aliveness patterns is possible: in smaller and larger socio-ecological systems, in organizations, teams, networks and collaboratives. The systems aliveness approach identifies six essential and generic principles. The principles represent a thorough synthesis of major writings on different explications of aliveness. These writings have emerged from multidisciplinary highly diverse knowledge streams such as architecture, biology, consciousness research, cognition science, neuroscience, leadership research, psychology, systems theory, organizational development and software development (for the background research on the principles see Kuenkel, 2019; Kuenkel & Waddock, 2019; Waddock & Kuenkel, 2019). More recently the reorientation towards aliveness has been taken up even in the realm of leadership practice (Hutchins & Storm, 2019).

In their relational interaction, the principles engender a pattern of mutually supportive conditions for aliveness to emerge. This dynamic flow of relationality can be seen as a co-construction of systems aliveness. It requires a patterned connectivity, which is particular to a certain system, respectively to a multiplicity of systems (see also Bertalanffy, 1968; Capra & Luisi, 2014). This means that how the generic principles get translated into the variety of realms and levels of systems that require transformations are dependent on the context and purpose of transformative change. Their translation can be used to diagnose or monitor systems aliveness as an identifiable current and transitory state, or guide the strategic design of transformative change processes. These different applications are elaborated and illustrated with examples in Part 3 of this book. The purpose of the underlying generic principles is to advance a new mindset that places the question ‘How can we steward aliveness in systems’? at the centre of advancing transformations (Kuenkel, 2019; Kuenkel & Waddock, 2019).

The six generic principles that constitute the systems aliveness approach support each other, each providing a lens and at the same time an entry point for generating or reviving vitality in a system. Figure 7.1 illustrates that their effect is in their togetherness. Like a compass with different lenses, they provide guidance for different realms of transformative change and need to be contextualized. They may overlap, but there is enough differentiation among them to justify presenting them as six distinct principles.

4.1 Principle 1: Generativity

All life is intentionally generative. Generativity is both the ability to co-create and to take care of future generations. This first principle reflects the urge of all living systems to continue into the future, including the capacity of natural and human systems (including organizations and institutions) to expand, renew, rejuvenate, replenish, and restore themselves in the process of staying resilient. It is this generative force of life that maintains and enhances the conditions for life to thrive. Life processes are never rigid and always ambiguous, as they balance intentional generativity among many forms of life and between smaller and larger units.

Translating Generativity as a generic principle into human competencies for transformation literacy means focusing on intentions for life-enhancing collective action. Advancing emotionally compelling future narratives around life-support systems and building accountability for future generations invigorates the human connection to systems aliveness and the capability to collectively shape future. In transformative change, enlivening this human capability is an important lever for building the momentum needed for maintaining or regenerating global and local conditions that further systems aliveness. This refers to the maintenance or regeneration of natural ecosystems as much as to building thriving social and economic ecosystems. An example for such an emerging narrative, which is propelled by the global COVID 19 pandemic, is the emerging discourse on the interlinkages between human health, ecosystems or even planetary health and the purpose of the economy. A focus on Life will fundamentally reorientate economic actions (Lovins et al., 2018). Identifying future narratives that reconnect people with Life are a core element of transformation literacy. Life as a reference point and basis for a future narrative is a unifying connection between multiple issue-based transformative change initiatives, such as the movement around regenerative agriculture, agroecology or reforestation; initiatives that drive renewable energies; regenerative urban design; the re-establishment of local economies or initiatives that revive community relations. Yet, with generativity in ever-growing complexity, life works with discernible system identities that allow for containment, belonging and identity. This leads to the second principle.

4.2 Principle 2: Containment

Life thrives on identity with permeable boundaries. All living systems need sufficient containment and boundaries for cohesive identities to emerge. But in order for life to thrive this containment needs to be permeable in the sense of adaptability and agility. Such permeable containment holds generativity in check and creates pathways for what Maturana and Varela (1987) mention as a system’s capability to develop as a result of perturbations in a combination of cyclical change and structural change.Footnote 6 Hence, cognition of other systems’ identities, the perception of belonging, purposeful connectivity and a negotiable degree of openness for transforming identities is an essential facet of living systems (Ashby, 2011; Capra & Luisi, 2014; Prigogine, 1996; Swanson et al., 2009).

Translating Containment as a generic principle into human competencies for transformation literacy means acknowledging the need for enabling structures, those that balance power and foster multiple purpose-driven communities, which connect in networked collective action. This can take the form of cross-institutional or multilateral collaboration, global alliance, or local coalitions. The recently emerging initiatives, movements, coalitions, alliances and partnerships focusing on different facets of sustainability transformations are testimony to the need to bring people together in intentional and transformative communities. Organizing collaborative change, for example, for combating biodiversity loss or fighting climate change, establishing ecocide as a crime against humanity, the reduction of plastic waste or increasing the sustainability of value chains, increasingly takes place in local to global networks across societal stakeholders or academic disciplines. These purposeful communities form meta-structures that generate different forms of permeable containment more suitable to overall systems aliveness. In that way, they model the future. If these communities are networked (and not in competition), they influence (or perturb) outdated institutional arrangements and create change systems capable of addressing complex sustainability challenges. Yet, any form of containment always leads to structures, without which Life could not thrive, but which tend to become rigid and ineffective. The openness for transformations and rearranged new structures requires another principle.

4.3 Principle 3: Novelty

Life is generously creative. While maintaining overall containment the process of life is constantly unfolding novel pathways and new identities. The creation of novelty is an essentially undetermined process, integrally and inextricably linked with life (Capra & Luisi, 2014; Kauffman, 2016; Zohar & Marshall, 1994). This happens through invention, adaptation, exaptation, learning or other features that engender innovation. It can be said that living systems create ‘experiments’ with the purpose to keep the whole intact while enhancing resilience (Holling, 1973). This suggests a new understanding of ‘growth’ as an urge to expand in negotiated contextuality, while creating conditions that enable mutually supportive systems to flourish without necessarily getting bigger in a linear sense (Jacobs, 2000). Novelty is an essential aspect of vitality and takes the form of abundance, manifested as greater complexity with more diversity (Weber, 2013).

Translating Novelty as a generic principle into human competencies for transformation literacy means engaging the human desire to find novel pathways, but guide innovation towards supporting regenerative practices. The topic of innovation is high on the agenda of change-makers for sustainability transformations, as climate change and the current planetary crisis requires novel pathways, rapid innovation and local creativity. Interestingly, the discourse on innovation and the rise of methodologies such as design thinking (Liedtka & Ogilvie, 2011) acknowledge that innovation does not happen in isolation. Rather, it is socially constructed and so much more effective, if built on encounters, conversations and exchange of ideas (Stamm, 2008). The process of reconnecting novelty with purpose is most palpable in the emerging discourse on the role of digitalization and the re-owning of data. Digitalization is a good example for the need to reorientate innovation purpose to serve ‘Life’ and flourishing societies rather than benefit large companies. This hints to the need for another principle that guides emergence of systems aliveness.

4.4 Principle 4: Consciousness

Life emerges from meaning-making cognition. Cognition is a general property of living systems, and human consciousness is the most complex manifestation of this general property (Maturana & Varela, 1991). Where consciousness studies, cognition theory, quantum physics and Buddhist as well as Chinese philosophy align is around the insight that mind and matter are intertwined (Bohm, 1980; Bohm & Hiley, 1993). Consciousness, and in the human realm, thought, or awareness, give rise to matter and vice versa (Macy & Brown, 2014; Sheldrake, 2011). It matters what we think and manifested reality influences our thought.

The translation of Consciousness as a generic principle into human competencies for transformation literacy is multifaceted. It means raising the human capability to reflect while acting and establishing metrics that help many people at the same time to notice progress. The term ‘proprioceptive’ captures this—the ability to notice what is happening, or even anticipate what will be happening while something is happening, and while we act. There is a global trend in the sustainability movement towards changing the ‘thinking’ of people, most profoundly that of decision-makers towards shifts in mindsets and paradigms. This ranges from campaigns and advocacy to scenario planning, future modelling, extensive dialogues and deliberations as well as many different forms of contemplative practices. The valid assumption of all these very different strategies is that a shift in consciousness—most often awareness—leads to different actions. This is especially the case, if people are able to reconnect with their humanity. But translating this principle into capability aspects of transformation literacy is also multifaceted, reaching into realms that may not obviously be connected. The state of the world suggests reflecting while acting should not only be an individual ability, but a collective capacity. Recognizing patterns of system aliveness (or the opposite) at a collective scale requires forms of agreed measurements that make it easy for many people at the same time to perceive a situation, a current state, a certain development, or what they consider progress. For example, there are many calls to overcome the misleading measure of economic societal progress, the GDP, because it is a globally orientating measurement that incentivizes exploitation of people and nature (Costanza et al., 2014). Instead, many actors suggest to redefine what economic and societal process is, and translate this into metrics that take the quality of life as centre of attention: Examples are the Gross National Happiness Index in Bhutan, The OECD Life Index, or the Wellbeing Economy Indicators (Hoekstra, 2020). Important for transformation literacy is the realization that metrics help people to understand and improve a situation. Yet, metrics can only become truly empowering as an element of cognition, when they are based on collective deliberations. This hints to another principle that guides systems aliveness.

4.5 Principle 5: Interconnectedness

Life requires networked diversity in constant reciprocal communication. Life processes are built on the ability of living systems (large and small) to change and evolve in mutual consistency with each other, and situationally appropriate. They always do so in the relationality of a certain context, which may be layered, but is always discernible. This contextual interconnectedness among the diverse subsystems leads to a balance between the various layers of systems. Communicative and mutually supportive relationships are at the core of life and a prerequisite for resilience (Folke et al., 2010; Holling, 1973; Ruesch & Bateson, 2006; Wheatley, 1999). System aliveness patterns are self-referential and recursive. One can say that systems talk to themselves (Weber, 2016). Their connectivity provides constant feedback to maintain their vitality. Many scholars have supported the insight that, at the quantum level, all life, including living and non-living systems, is connected (Bohm, 1980; Capra, 1995; Capra & Luisi, 2014; Weber, 2013; Wheatley, 1999; Zohar & Marshall, 1994). Modern biology has now given evidence to the hypothesis that forest are interconnected communicative systems in mutual support. The same is true for societies. They are built on relationship patterns as well as a shared context of meaning sustained by continuous conversations (Luhmann, 1990). The human capability to converse, interact, gain insight, communicate, learn iteratively and adjust behaviour is a manifestation of this principle.

The translation of Interconnectedness as a generic principle into human competencies for transformation literacy means building transformative collective action on forms of structured dialogue and multi-level governance mechanisms that are contextually appropriate. They provide continuous feedback, respectively, iterative learning opportunities for transformative change. The key to life-enhancing communication is mutual respect for diversity. This can range from structured multi-level stakeholder consultations to more reflective conversational spaces. For example, it manifests in issue-related stakeholder governance systems for water or natural resource management, collaborative partnership in sustainable supply chains, or the establishment of governance structures for global commons (Ostrom, 2015). Well-functioning governance systems are at the forefront of sustainability transformations in the Anthropocene (Steffen et al., 2007) for which the variety of socially constructed realities need to be explored and harvested for a sustainable future. One results of such structures dialogues are agreements that safeguard overall systems aliveness. This hints to the last principle.

4.6 Principle 6: Wholeness

Life safeguards integrated wholes. Living systems are always integrated entities, and they are constituted of identifiable yet both parallel and nested ‘wholes’ or holons (Koestler, 1968) that mutually enhance each other. These wholes exist at multiple levels and provide embeddedness, identity, coherence and orientation. They create mutual consistency, always in relation to a next level whole (Sahtouris, 2000). The architect Alexander (2002) as well as the quantum physicist Bohm (1980) note that system aliveness emerges from an underlying potentiality of wholeness. In Bohm’s term, this is called the ‘implicate order’. In Alexander’s description, it is the degree of life in a certain space. Swanson et al. (2009) argues that living systems form integrated wholes as well as differentiation and co-creatively emerge to higher levels of complexity.

The translation of Wholeness as a generic principle into human competencies for transformation literacy has different facets that serve the same underlying intention: to enhance the human capacity to relate to the next level whole and acknowledge the need to safeguard the larger entity to the benefit of smaller entities. This also means to help people see the bigger picture and create guiding regulations as a result of negotiating the needs of the commons, the collective and those of individuals. The aforementioned trend, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, to increasingly refer to the health and integrity of our planet is an indication for a shift in consciousness that enlivens this principle. Not all safeguarding requires regulatory frameworks, but too little, or too weak regulations or binding agreements, especially those at the multilateral level, endanger the life of future generations. Where regulatory approaches fail, it is increasingly the emotional connection to a larger story of the world, to a bigger purpose that draws people into action and advocacy. For example, in mobilizing responsible collective action to halt climate change, safeguard or regenerate biodiversity, or turn to green energy production. The increasing use of the visual image of the planet in transformative initiatives is testimony to a growing trend to adopt more responsibility for the whole. Yet, agreements to safeguard the commons, such as climate agreements, environmental regulations, tax systems, or environmental regulations that safeguard landscape ecosystems are necessary, because they also guide resource allocations, financial flow and investments. Hence, important for transformation literacy is the ability to take a systemic view—from local to global. This also means to move beyond competition in transformative change initiatives, and connect various different initiatives around an issue, or combine them at different levels to increase their impact.

5 A Stewardship Architecture for Transformation Literacy

Systems aliveness rests on diversity in complementarity and reciprocity, and it requires feedback loops of communication. The emergence of an underlying potential of vitality and resilience comes about as a result of this relational interdependency—in a physical or mental space as well as in visible interaction between people. In human systems, attention to the principles creates the condition for aliveness to emerge. Moreover, aliveness patterns emerge in fractals, which connect subsystems with each other and nested systems within larger systems (Sahtouris, 2000; Sheldrake, 2011). What is known from purely ecological systems, is also valid for human systems as well as human–ecological interactions: The more biodiverse subsystems achieve a dynamic vitality and connect with each other, the more vitality they create in the overall system. Vitality spreads. This is a fundamental insight for transformations literacy, because it is the connected vitality or systems aliveness that furthers transformations. The capability to identify aliveness patterns that model regenerative practices, to foster and connect them, and to safeguard their emergence is the essence of becoming transformation literate. System aliveness is never a stable state, but consists of multiple connectivity processes in dynamic balance that allow for creative and agile responses to disturbances. Life strives for more life, and also for purpose-driven beauty without ever reaching perfection. But even under the most severe conditions of destruction, which we may experience as a result of climate change and biodiversity loss, the intentional urge of life to continue will have the inherent capacity to reconstruct patterns of aliveness, hence to adapt, regenerate and revive Life. If we learn to support this at scale, we can change the current life-endangering trajectories. This is at the core of a collective stewardship approach in transformation literacy. Across sectors, institutions, and nations, multiple actors need to drive simultaneous efforts towards regenerative civilizations, which may emerge in different forms and for which not all pathways can be prescribed in detail. The envisaged transformative change will need to be radical, if humankind wants to rescue its future on this planet, but they will occur in an incremental way (Goepel, 2016). Transformations will and must evolve in multiple different ways, and there is no recipe that fits all global and local contexts (Loorbach, 2007). Considering the complexity and multitude of the task, which lies ahead of us, these transformative efforts cannot be managed, controlled or even steered. They need to be stewarded collectively with a degree of humility that pays tribute to the pluriverse world and acknowledges the end of the westernized cultures’ dominance in the future-making. What is needed is a dynamic of mutually supportive and interacting self-organization, combined with multilateral agreements and regulatory guidance. Transformation literacy, then, is the humble acceptance of stewarding transformative change towards regenerative civilizations, while acknowledging that there will be many different pathways and practices. Table 7.1 shows how the generic principles can be translated into stewardship tasks that centre on Life as the essence of a regenerative civilizational future.

Many of these stewardship tasks are already happening in the global sustainability and transformation community. But there is a strong tendency of actors to focus on one or a few of the generic principles and the related stewardship tasks. However, it is the relational interaction of all principles that will help accelerate transformations. The stewardship architecture provides guidance for the design of small- and large-scale transformative change. Rising awareness of the complementarity of approaches and pathways could help actors see the patterned relationship between different transformative strategy. It will support them to get out of competition or insistence on owning the right path, and instead guide them to plan relational and reciprocal interventions towards regenerative systems.

6 Conclusion: Transformation Literacy Means Stewarding Systems Aliveness

In the generic process of Life and co-evolution, human beings, like the rest of nature, are in the constant conscious or unconscious, pursuit of patterns of aliveness. This is normal and the individual pursuit of aliveness and resilience needs to be constantly negotiated with overall systems aliveness. Yet, the current endangered state of the world is the symptom of a mindset of disconnection from the whole. In such a mindset, the pursuit of aliveness is individualistic, most often material-bound, and transitorily achieved at the expense of other peoples or nature’s aliveness. However, there is beginning hope that the increasingly obvious sustainability challenges revive the human ability for reflective consciousness. This would help us to go beyond an individualistic interpretation and manifestation of systems aliveness and enable us to learn to recognize and regenerate system aliveness as the quality of a patterned composition of mental or physical structures in natural or human system—small and large. The systems aliveness approach opens the possibility to use the six generic principles as an underlying compass and consciously translate them into stewardship measures for human and planetary wellbeing. The above-mentioned new trend towards Life as a reorientation for social, ecological and economic collective action pays tribute to this emerging possibility.

Life processes operate with the above principles never in isolation from each other. The relationality works rather like the dynamic interaction and balance of an orchestra that creates musical variety, harmony and resonance in the togetherness of playing. Balance means that at times there is more attention to one set of instruments and at other times to other instruments, but the orchestra as a whole never loses sight of the overall patterned flow of the music. The same applies to the stewardship architecture. Each of the stewardship tasks is an entry point towards systems aliveness, but depending on the situation each entry point may have to be emphasized or prioritized for a certain period of time. Transformation literacy requires to not lose sight of the other principle-based stewardship tasks and bring them in over time.

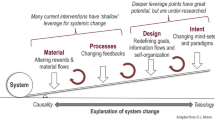

Climate change and the transgression of planetary boundaries are global patterns that indicate a massive reduction of overall systems aliveness. Unhalted, it will not only increasingly impact social and economic patterns, but spiral towards tipping points: runaway feedback loops would increase the speed of diminishing systems aliveness towards a ‘Hothouse Earth’ (Steffen et al., 2018). This is why an evolutionary shift in consciousness among humankind needs to be supported. How people see reality or the planet Earth—as a machine to be repaired or a living organism to be enlivened—influences their feelings, their thinking, and above all their sense of responsibility. Such shifts (or reorientations) of mindset are a cornerstone of shared social agreements which lead to a redefinition of goals and constitute the most important leverage points for transformative change (Meadows, 1999). The emerging trend to take Life as a reference point for future collective behaviour is the beginning of this evolutionary shift. But operationalizing this trend requires new approaches, methodologies and capabilities. Transformation literacy means that many more societal actors understand the patterns and dynamics of socio-ecological-economic change, and how they compromise or foster system aliveness. The six generic principles function as a meta-guide for the development of methodologies for diagnosing patterns and planning concrete intervention strategies to steward systems aliveness. They foster a reconnection with an old human dream of human beings becoming a humble partner and caretaker of Life.

Notes

- 1.

Many articles and blogpost have suggested mindshifts as a result of the pandemic, a provocative summary of suggested shifts can be found in a blogpost by Chandran Nair (Nair 2021).

- 2.

Vitality, vital and revitalizing were mentioned as strategic terms 7 times, e.g. in “A New Vitality for Europe”, source: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_20_1655; retrieved 3rd January 2021.

- 3.

Section About: Earth is Our Home. https://globalcommonsalliance.org/about/. Retrieved 3rd January 2021.

- 4.

See: https://www.degrowth.info/en/what-is-degrowth/ retrieved 3rd January 2021.

- 5.

- 6.

See the Santiago Theory of cognition (Maturana and Varela 1991).

References

Alexander, C. (1979). The timeless way of building (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

Alexander, C. (2002). The nature of order. An essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe: Book I—The phenomenon of life. The Center for Environmental Structure.

Alexander, C. (2004). The nature of order. An essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe: Book IV—The luminous ground. The Center for Environmental Structure.

Alexander, C. (2005). The nature of order. An essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe: Book III—A vision of a living world. The Center for Environmental Structure.

Ashby, W. R. (1962). Principles of the self-organizing system. In: H. von Foerster & G. W. Zopf (Eds.), Principles of self-organization. Pergamon.

Berman, M. (1981). The reenchantment of the world. Cornell University Press.

von Bertalanffy, L. (1968). General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. George.

Bohm, D. (1980). Wholeness and the implicate order. Routledge.

Bohm, D., & Hiley, B. (1993). The undivided universe. An ontological interpretation of quantum theory. Routledge.

Capra, F. (1995). Deep ecology: A new paradigm. In: Deep ecology for the 21st century (2nd ed., pp. 19–25). Shambhala.

Capra, F., & Luisi, P. L. (2014). The system’s view of life—A unifying vision. Cambride University Press.

Capra, F., & Mattei, U. (2015). The ecology of law: Toward a legal system in tune with nature and community. Berrett-Koehler.

Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Giovannini, E., Lovins, H., McGlade, J., Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. (2014). Development: Time to leave GDP behind. Nature, 505(7483), 283–285. https://doi.org/10.1038/505283a

Churchman, C. W. (1967). Guest editorial: Wicked problems. Management Science, 14(4), B141–B142.

Conner, C. (2015). A people’s history of science. Bold Type Books.

Deluca, D. (2016). Realigning with nature. White Cloud Press.

Elgin, D. (2009). The living universe. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Kindle-Version.

Elworthy, S. (2014). Pioneering the possible. North Atlantic Books.

Eisler, R. (1988). The chalice & the blade. Our history, our Future. Harper & Row.

Finidori, H., Borhini, S. G., & Henfrey, T. (2015). Towards a fourth generation pattern language: Patterns as epistemic threads for systemic orientation. In: Proceedings of the Purplsoc (Pursuit of pattern languages for societal change) Conference 2015, Danube University, Krems, Austria.

Fioramonti, L. (2017).Wellbeing economy. Success in a world without growth. Palgrave Macmillan Publishers Johannesburg.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S. R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T., & Rockstrom, J. (2010). Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability.

Fullerton, J. (2015). Regenerative capitalism. Capital Institute, April, 2015. Accessed Aug 23, 2016, from http://capitalinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2015-Regenerative-Capitalism-4-20-15-final.pdf.

Gabriel, R. P. (1996). Patterns of software. Oxford University Press.

Goepel, M. (2016). The great mindshift. How a new economic paradigm and sustainability transformations go hand in hand. Springer International Publishing.

Harding, S. (2006). Animate earth, science, intuition and gaia. Green Books.

Hawken, P. (1993). The ecology of commerce. A declaration of sustainability. HarperBusiness.

Hawken, P. (2007). Blessed unrest: How the largest movement in the world came into being and why no one saw it coming. Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-03852-7

Hoekstra, R. (2020). Measuring the wellbeing economy: How to go beyond-GDP. Accessed May 7, 2021, from https://wellbeingeconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/WeAll-BRIEFINGS-Measuring-the-Wellbeing-economy-v6.pdf.

Hollensbe, E., Wookey, C., Hickey, L., George, G., & Nichols, C. V. (2014). Organizations with purpose. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.4005

Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23.

Hutchins, G., & Storm, L. R., (2019). The DNA of life-affirming 21st century organizations. Wordzworth Publishing. Kindle-Version.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York: Vintage.

Jacobs, J. (2000). The nature of economies. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. Ort: Kindle-Version.

Kauffman, S. (2016). Humanity in a creative universe. Oxford University Press.

Kelso, J. S. (1997). Dynamic patterns: The self-organization of brain and behavior. MIT Press.

Korten, D. C. (2007). The great turning: From empire to earth community. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Kuenkel, P. (2019). Stewarding sustainability transformations: An emerging theory and practice of SDG implementation. Springer.

Kuenkel, P., & Waddock, S. (2019). Stewarding aliveness in a troubled earth system. Cadmus Journal, 4(1). http://cadmusjournal.org/article/volume-4/issue-1/stewarding-aliveness-troubled-earth-system.

Liedtka, J., & Ogilvie, T. (2011). Designing for growth: A design thinking tool kit for managers. Columbia University Press.

Loorbach, D. (2007). Transition management. New mode of governance for sustainable development. Doctoral Dissertation. Erasmus University, Rotterdam.

Lovins, H. L., Wallis, S., Wijkman, A., & Fullerton, J. (2018). A finer future. Creating an economy in service to life. New Society Publishers.

Luhmann, N. (1990). Essays on self-reference. Columbia University Press.

Macy, J., & Brown, M. (2014). Coming back to life. New Society Publishers.

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1991). Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living (Vol. 42). Springer.

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1987). The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding. New Science Library/Shambhala Publications.

McKenzie, J., Woolf, N., Van Winkelen, C., & Morgan, C. (2009). Cognition in strategic decision making: A model of non-conventional thinking capacities for complex situations. Management Decision, 47(2), 209–232.

Meadows, D. (1999). Leverage points. Places to intervene into a system. Sustainability Institute.

Merchant, C. (1980). The death of nature. Women, ecology and the scientific revolution. HarperOne.

Mies, M., & Shiva, V. (1993). Ecofeminism. Zedbooks.

Nair, C. (2021). The Covid disaster in India shows that the future is biological, not digital. Accessed May 2, 2021, from https://lite.cnn.com/en/article/h_1cfd5991bfc5bc492be47f5b781ad1f1.

OECD. (2015). System innovation. Synthesis report. Accessed June 30, 2017, from https://www.innovationpolicyplatform.org/sites/default/files/general/SYSTEMINNOVATION_FINALREPORT.pdf.

Ostrom, E. (2015). Governing the commons. The evolution of institutions for collective action (Canto Classics), Reissue Edition. Cambridge University Press. Kindle-Version.

Otto, I. M., Donges, J. M., Cremades, R., Bhowmik, A., Hewitt, R. J., Lucht, W., Rockström, J., Allerberger, F., McCaffrey, M., Doe, S. S. P., Lenferna, A., Morán, N., van Vuuren, D. P., & Schellnhuber, H. J. (2020). Social tipping dynamics for stabilizing Earth’s climate by 2050. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(5), 2354–2365. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1900577117

Prigogine, I. (1996). The end of certainty: Time chaos and the new laws of nature. The Free Press.

Raskin, P. (2016). Journey to Earthland: The great transition to planetary civilization. Tellus Institute.

Raskin, P. D., Electris, C., & Rosen, R. A. (2010). The century ahead: Searching for sustainability. Sustainability, 2(8), 2626–2651. https://doi.org/10.3390/su2082626

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin III, F. S., Lambin, E., & Foley, J. (2009). Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecology and Society 14(2), 32.

Ruesch, J., & Bateson, G. (2006). Communication: The social matrix of psychiatry. Transaction Publishers.

Sahtouris, E. (2000). Earthdance: Living systems in evolution. iUniverse.

Sheldrake, R. (2011). The presence of the past. Morphic resonance and the habits of nature. Icon Books.

von Stamm, B. (2008) Managing innovation design and creativity (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Steffen, W., Rockström, J., Richardson, K., Lenton, T. M., Folke, C., Liverman, D., ... & Donges, J. F. (2018). Trajectories of the earth system in the anthropocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(33), 8252–8259. https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/early/2018/08/07/1810141115.full.pdf.

Swanson, G. A., & Miller, J. G. (2009). Living Systems Theory. Systems Science and Cybernetics: Synergetics, 1(System Theories), 136–148.

Waddock, S., & Kuenkel, P. (2019). What gives life to large system change? Organization & Environment.https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026619842482SAGEPublishing.

Waddell, S., Waddock, S., Cornell, S., Dentoni, D., McLachlan, M., & Meszoely, G. (2015). Large systems change: An emerging field of transformation and transitions. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 58, 5–30.

Wahl, D. (2016). Designing regenerative cultures. Triarchy Press.

WBCSD (World Business Council for Sustainably Development). (2020). From Challenge to opportunity. The role of business in tomorrow’s society. Accessed Apr 15, 2021, from https://www.catedrarses.com.do/Portals/0/Documentos/CRSES/From%20challenge%20to%20opportunity.%20The%20role%20of%20business%20in%20tomorrow%27s%20society.pdf.

WBGU—Wissenschaftlicher Beirat der Bundesregierung Globale Umweltveränderungen. (2019). Unsere gemeinsame digitale Zukunft. WBGU, Berlin. Accessed May 10, 2021, from https://www.wbgu.de/fileadmin/user_upload/wbgu/publikationen/hauptgutachten/hg2019/pdf/wbgu_hg2019.pdf.

Weber, A. (2013). Enlivenment. Towards a fundamental shift in the concepts of nature, culture and politics. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

Weber, A. (2016). Biology of wonder: Aliveness, feeling and the metamorphosis of science. New Society Publishers.

Weizsäcker, E. U., & Wijkman, A. (2018). Come on! Capitalism, short-termism, population and the destruction of the planet. Springer.

Wheatley, M. (1999). Leadership and the new science, discovering order in a chaotic world. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wulf, A. (2016). The invention of nature: The adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt, the lost hero of science. John Murray.

Yamash’ta, S., Yagi, T., & Hill, S. (2018). The Kyoto manifesto for global economics. Creative Economy Series. Springer Singapore. Kindle-Version.

Zohar, D., & Marshall, I. (1994). The quantum society: Mind, physics and a new social vision. Quill/William Morrow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kuenkel, P. (2022). The Systems Aliveness Approach—Shifting Mindsets from Navigating Emergency to Stewarding Wellbeing on a Healthy Planet. In: Künkel, P., Ragnarsdottir, K.V. (eds) Transformation Literacy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93254-1_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93254-1_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-93253-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-93254-1

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)