Abstract

The types of food retailers operating in cities in sub-Saharan Africa and their physical distribution contribute to the spatial characteristics of food systems. As smaller urban areas expand in terms of both population and spatial extent, the importance of ensuring both physical and financial access to food throughout a city is critical for ensuring sustainable food systems. In this chapter, we use data collected from two smaller cities, Mumbwa and Monze, Zambia. Using spatial analysis, we investigate how household food purchasing behaviour differs based on the use of three different types of food retailers: traditional markets, small grocers and street vendors. We find significant hotspots of food purchasing behaviour in both Mumbwa and Monze; specifically, households located in the centre of each city purchase primarily from traditional markets, while households near the periphery use a mixture of street vendors and small grocers. Mumbwa households located in hotspots of street vendor purchases have the worst household food access, while Monze households have relatively similar food access regardless of whether they are in hotspots. Although spatial characteristics are often absent from studies related to food security in sub-Saharan Africa, our case study results suggest that food access not only varies spatially, but so does the relationship between households and the food retailers they purchase from. Our findings contribute to the ongoing discussion surrounding transformation of food systems, the emergence of smaller African urban areas and how spatial analysis methods can be applied to study food access.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In urban sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the food retailer environment is made up of different food retailers offering both fresh and processed products in different quantities and available at different prices (Wanyama et al., 2019). Access to food of different quantities and prices is essential for low-income urban consumers because they often shop at multiple retailers to meet their food needs (Battersby & Haysom, 2018). Three important food retailers that low-income households rely on are street vendors, small grocers and traditional public markets. Street vendors typically provide smaller quantities of food at more affordable prices and typically sell fresh fruits and vegetables. Small grocers may sell fresh produce, but they typically sell processed and non-perishable foods such as cooking oil, packaged foods, soft drinks and maize-meal. Traditional markets provide fresh foods and meat, as well as processed foods. Traditional markets sell directly to consumers and are used as wholesalers by street vendors and small grocers.

The food retailer environment in SSA is rapidly transforming due to a number of large-scale processes, including urbanization throughout the region, the growth of international supermarket chains and the ongoing transitions in dietary preferences and habits (Haysom & Tawodzera, 2018; Peyton et al., 2015; Reardon & Zilberman, 2018; Seto & Ramankutty, 2016). These large-scale changes have implications for food access and food security at the city, household and individual levels. As secondary and tertiary urban areas (as opposed to primary urban areas, such as national capitals) expand in population and size, it is important for these urban food systems to be able to equitably meet the food access needs of all urban consumers, regardless of their socio-economic status or their location within the city. It is necessary to understand which retailers operate in a city and its residential areas, how consumers interact with the different retailer types and how food access varies both financially and physically with respect to those food retailers.

A considerable amount of research highlights the relationship between food access in urban SSA and household economic characteristics, such as employment, income and food sourcing (Blekking et al., 2020; Davies et al., 2020; Demmler et al., 2017; Tuholske et al., 2020), but less research addresses the spatial aspects of the relationship between consumers and food retailers. To understand the spatial characteristics of urban food systems and food retailers, we use primary data collected in Monze and Mumbwa, Zambia. There are three key pieces of information underpinning this study: the location of household within each respective city; the frequency with which households purchase food from street vendors, small grocers and traditional markets during a 14-day period; and the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) score for each household. We then use spatial analysis to determine hotspots of retailer use in order to understand how space relates to food purchasing behaviour. Once hotspots are identified, we compare household characteristics of those within and outside of the hotspots in order to understand the relationship between food purchasing behaviour and the spatial characteristics of the urban food retailer environment.

Background

In general, greater rates of urbanization lead to higher rates of development, but this has not occurred in SSA (Ravallion, 2007). This is cause for concern, considering urbanization rates have steadily increased over the past 20 years to the point that SSA is currently the site of the most rapid rates of urbanization in the world (UN-DESA, 2018). At the same time, urban poverty has increased, with the increase in the share of poor households in urban areas sometimes outpacing the rate of overall population increase (Tefft et al., 2017). Because urbanization in SSA has not led to expected improvements in development, and ultimately livelihoods, ensuring equitable food access in terms of economic and physical access is critical to ensuring urban food security. Unfortunately, it is hard for Southern African governments to effectively plan for equitable food systems because there are many different actors with competing interests (AGRA, 2020). The little planning that has occurred has been largely targeted towards modernizing urban areas via development initiatives that favour larger retailers, such as international supermarket chains (Battersby, 2017). However, in their effort to push for more modern cities, private firms and the government are not transforming local urban food systems sustainably and equitably by including smaller, local food retailers.

Urbanization in SSA and other regions of the Global South tends to manifest as spatial extensification, rather than intensification via greater population densities (Nagendra et al., 2018). Extensification often leads to rapid urban expansion with uneven or inconsistent levels of infrastructure and development, characterized by urban sprawl outward from the city centre with patches of undeveloped land between developed areas (Cobbinah & Amoako, 2012). Recently settled areas are not necessarily low-income areas, but can also feature middle- and upper-income areas. Heterogeneous spatial expansion of urban areas in SSA can outpace the ability of local governments to adequately provide required services such as water, sanitation and roads (Cohen, 2006). Because of the limited services and relatively low population density, few bricks-and-mortar food retailers (such as supermarkets, grocers, butchers or traditional markets) exist in newly developed, unplanned settlements and smaller food retailers (such as street vendors), often fill this spatial void. Street vendors are well-suited for this role because they have the ability to pick up and move in order to operate where consumers live or travel, and they provide food in the quantities and at the prices consumers require (Battersby & Watson, 2018).

In Zambia, urban agriculture is not substantially associated with household food security (Davies et al., 2020). Instead, urban consumers must purchase food from food retailers (Crush & Frayne, 2010). In general, low-income households spend a larger share of their income on food (Cohen & Garrett, 2010), so decreased incomes or increased food prices can present challenges to household food access (Caesar & Crush, 2016). Even holding income constant, households must also balance the costs associated with other living expenses, such as transportation, housing and energy (Pothukuchi & Kaufman, 1999). To stretch their purchasing power, urban households often visit multiple food retailers to meet their food needs (Battersby & Watson, 2018). Considering the relationship between food access and economic characteristics is important and well understood, but it does not tend to take into account the association between food access and space.

Both food access and purchasing power can exhibit spatial patterns, like the spatial patterns associated with poverty (Giroux et al., 2020). How food retailers are distributed throughout an urban area can create disparities in household food access to the point that food security is reduced for some. In the Global North, this type of spatial disparity in food access is often referred to in terms of food deserts. However, applying this term and its framing to the food retailer environment in the Global South is less straightforward (Battersby and Crush, 2014). The confluence of legacies of colonialism, global capitalism, rapid urbanization and lack of local food planning and policy means that the spatial dynamics of food access unfolds in ways that are not well understood. Spatial features of these food systems are of paramount importance and by mapping and analysing the diversity of food retailers that exist and the ways households rely on them, we begin to identify the roles of different food retailer types in ensuring equitable food access across space, while also taking household economic factors into consideration.

Data and Methods

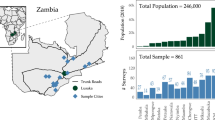

We analyse household-level data collected from two smaller urban areas in Zambia: Mumbwa and Monze. As of 2019, Zambia’s population was about 17.4 million (Bank of Zambia, 2019). As in other countries in Southern Africa, smaller urban areas in Zambia are undergoing urbanization at a rate of approximately 2.5% annually (Zimmer et al., 2020). Both Mumbwa and Monze serve as district capitals, have populations below 50,000 people, and their designated boundaries are less than 30 square kilometres. Both urban areas feature numerous food retailers that range in market share and placement throughout the city, such as traditional markets, wholesalers, small grocers, butchers and street vendors. Monze has three traditional markets, while Mumbwa has one. Notably absent from Mumbwa and Monze are supermarket chains common in the region such as Shoprite or Pick n Pay. Since the Mumbwa household survey was conducted in 2019, the supermarket chain Choppies has started to operate there. Mumbwa is located approximately two hours west of Lusaka, the national capital, and Monze is approximately three hours south of Lusaka. Both cities are located along paved roads and serve as important economic hubs for farmers in the surrounding area.

In Monze, we collected data from 219 households in June 2018. In Mumbwa, we collected data from 135 households in June 2019. In both cities, we selected residential areas for sampling, in consultation with local government officials. We used a stratified area random sampling technique to sample households from within low- and low-middle-income residential areas in both cities (Fig. 8.1) (Montello & Sutton, 2006). The northwest portion of Mumbwa was not sampled because that area is primarily higher-income residential housing. In Monze, the northeast portion of the city contains higher-income households and was also not sampled. Sampled residential areas represent both formally designated and informally established residential areas. We sampled a minimum of 30 households in each selected low- and low-middle-income residential area in order to ensure geographic distribution across areas of interest throughout the city and to ensure sufficient observations for purposes of statistical analysis.

One household member over the age of 18 and with knowledge of the household and its members responded to the survey. The survey included modules regarding household member demographics, employment characteristics and food purchasing and consumption behaviour, including the frequency with which household representatives reported purchasing food from street vendors, small grocers and traditional public markets over the prior 14-day period. We define street vendors as individuals selling food along the side of the road. Small grocers are defined as individually owned stores selling an array of products, including food. Traditional markets can either be managed formally by the city council or informally by a cooperative or community group. In our analysis, we consider small grocers inside the demarcated boundary of a traditional market to be part of the market, not separate grocers.

Spatial analysis is commonly used in public health research in SSA (Chimoyi & Musenge, 2014; Sedda et al., 2018), but less often in food systems and food security research. However, the application of spatial analysis to these types of research can provide a nuanced approach to understanding how household-level outcomes vary across space. In this research, we use hotspot analysis (Getis-Ord Gi* statistic) to discern whether there are areas of the respective cities where households rely more heavily on particular retailers. This analytical approach identifies statistically significant clusters, called hotspots, of high values for the variable of interest. In this case, hotspots delineate areas where households with high values (more frequent use of particular food retailers) are surrounded by other households with similarly high values. When household values are substantially different from those of the global population, a statistically significant value is observed. It is important to note that hotspot analysis uses values from the individual and neighbouring households to calculate the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic. Only when the statistic is calculated and found to be statistically significant are households identified as hotspots. Some households may be identified as hotspots when their neighbours are not and will therefore appear to be spatially independent.

A spatially independent household indicates an area in space where high values are occurring, even if neighbouring households with high values are not indicated as hotspots. For example, a household with a value of 14 for the number of times it has visited a traditional market in the past 14 days, surrounded by other households with the same or similarly high values will be indicated as a hotspot, as will the other households with similarly high values. However, a value of 14 surrounded by low values will be represented as an independent hotspot, while the same value surrounded by a mixture of high and low values will likely not be indicated as a hotspot. We use Fixed Distance Band to conceptualize the spatial relationship. A Fixed Distance Band creates a weight matrix that restricts the use of observations outside of a set distance buffer. Using this method, neighbouring observations within a fixed buffer of 500m receive a weight of 1, while observations beyond the fixed buffer receive a weight of 0. We use hotspots of greater than 95% statistically significant confidence to illustrate our findings more clearly.

We then compare characteristics of the households inside and outside the hotspots. We pay particular attention to differences in household food access, as measured using a condensed version of the HFIAS (rHFIAS). This version of rHFIAS was amended by local collaborators to represent a more culturally appropriate metric. The condensed version retained the four-week recall period suggested by Jennifer Coates et al. (2007) and measured the frequency of occurrences for each question. Possible responses were “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes” or “often”. Because the questions pertain to negative outcomes (i.e. lack of food access), lower values represent better food access, while higher values represent poor food access. For this condensed version of rHFIAS, values can range from 0 (better food access) to 15 (worse food access).

Results

In Mumbwa, households are smaller, they visit food retailers less often, and the rHFIAS score is higher, indicating poorer food access, despite spending more per capita on food for the household (Table 8.1). The higher household food cost per capita per month in Mumbwa is due, in part, to the two surveys being conducted in separate years. In 2018, the average exchange rate was 10.45 ZMK to 1 USD, while one year later, in 2019, the kwacha had devalued to a rate of 12.91 ZMK to 1 USD. Households in Mumbwa are, on average, a 26-min walk from the centrally located traditional market, while in Monze households are approximately a 22-min walk from one of the three traditional markets.

Street vendor hotspots are in the top row of panels, traditional market hotspots are identified in the middle row of panels and small grocer hotspots in the bottom row (Fig. 8.2). All panels in the left column represent Monze households and hotspots, while all panels in the right column represent the same for Mumbwa. In Monze, we find two hotspots of street vendor patronage: the largest cluster, to the northwest of the city centre, is made up of 19 households; the second cluster, to the southeast, is made up of five households (Panel A). Three main household clusters and one spatially independent household are identified as hotspots for purchases from traditional markets in Monze (Panel B). The large cluster located towards the southern part of the city is located near the Munungu market, while the two clusters to the north are located near the city’s other two traditional markets. Our spatial analysis indicates three clusters of households identified as hotspots for making frequent purchases from small grocers (Panel C). The two hotspots located south of the spatially independent household are near the Munungu market, while the cluster located in the west is near the settled periphery of the city (Fig. 8.2).

In Mumbwa, we find two areas of households identified as street vendor hotspots. The largest of the two areas is made up of 10 households, while the smaller area to the east is made up of two households (Panel D). Spatial analysis identifies two areas of hotspots for households making frequent purchases from traditional markets, plus one spatially independent household in Mumbwa (Panel E). The two main clusters are located near the only traditional market in the city. Lastly, we find one small grocer hotspot of households located in the east and two spatially independent households: one located north of the town centre and one located to the southwest of the town centre (Panel F).

Our findings suggest that Monze and Mumbwa exhibit similar spatial patterns regarding street vendors. In both cities, households located further from the town centre purchase more frequently from street vendors. Households living near the city centre in both urban areas use street vendors or small grocers less frequently (Panels B and E), which suggests that traditional markets play a stronger role in providing food for centrally located households. It is important to note that Monze has three traditional markets, while Mumbwa has only one. As a result, there are multiple traditional market-related hotspots spread across Monze, while in Mumbwa the hotspots are located near the single market.

We find that households in street vendor hotspots in both Mumbwa and Monze visit street vendors more than 10 times on average in a 14-day period (Table 8.2). A noteworthy difference between the two groups of households is that despite the high frequency of visits to street vendors by households in both urban areas, Mumbwa households in the street vendor hotspots have worse food access (6.75) as compared to households in street vendor hotspots in Monze (3.88). In Monze, households in street vendor hotspots have nearly twice the assets that their outside hotspot counterparts do. In Mumbwa, the asset index is only slightly different between households inside and outside the street vendor hotspot. Mumbwa households in traditional market hotspots have similarly worse food access (6.31) compared to market hotspot households in Monze (3.97). Mumbwa households in market hotspots have marginally greater assets than those outside the hotspots. For both Mumbwa and Monze traditional market hotspot households, they are about half the distance to the nearest traditional market than outside hotspot households. This suggests that these households are centrally located in their respective urban area, near to where traditional markets are also located, and that this proximity improves their food access. Furthermore, these results indicate that financial accessibility is not necessarily the limiting factor for why households visit these food retailers, and that households that buy food from these retailers are not necessarily food insecure.

Discussion

Given that most urban areas in SSA are growing in terms of population and spatial extent, there exists a need to consider the spatial process of urban growth in the context of food retailers. In Zambia, efforts to modernize the urban areas have led to policies that favour large retailers such as supermarkets (Abrahams, 2010); however, this does not appear to support sustainability and equitability of food access for low-income urban households. To transform food systems in smaller urban areas in SSA, policymakers must take a proactive approach to integrating street vendors and other small food retailers in parallel to supermarkets (Skinner, 2018). Consider that in Mumbwa a new supermarket opened since this study was conducted. Local news outlets report that the impetus for these openings comes from the favourable investment policies set forth by the Zambian government, which encourages “chain store[s] to rapidly expand [their] business prospects across the country” (Jere, 2020). The same enthusiasm to integrate street vendors and other small, local retailers into food systems is absent in Zambia. By exclusively considering the role of large food retailers, officials and investors are ensuring that food access is not equal, in particular for low-income households. Because urban consumers require many types of food retailers to meet their food needs (Wanyama et al., 2019), a one-size-fits-all approach to transforming food systems in smaller urban areas will likely have limited success in ensuring food access as smaller cities grow. To ensure a strong, equitable environment for a variety of retailer types, policy must focus on including smaller, local food retailers.

The spatial clustering of households that purchase food from street vendors reflects aspects of the spatial distribution of poverty and limited food access, and reaffirms the importance of street vendors as nodes within the overall food system. Street vendors not only facilitate food access for poorer households, but they also play an important role in ensuring equitable physical access across an urban area (Battersby & Watson, 2018); however, our analyses show that the association among poorer households, spatial location of vendors and households, and food access can be mixed. Consider that households in the street vendor hotspots in Mumbwa are, on average, a 20-min walk from the nearest traditional market, and spend substantially less per month on food than non-hotspot households. In Monze, households within the street vendor hotspot are, on average, a 39-min walk from the nearest traditional market and spend marginally more on food per month as compared to households outside these hotspots. In both instances, households rely substantially on street vendors, but associated household characteristics vary between the study sites. Assuming either household economic characteristics or spatial proximity to retailers are the limiting factor to food access does not consider other structural factors related to food access, including other non-food costs, employment opportunities, gendered aspects or even environmental challenges.

Unfortunately, street vendors are typically left out of urban planning initiatives in favour of large, modern food retailers such as supermarkets. Rather than viewing street vendors as assets within the food retail environment, the Zambian government often targets street vendors through policies and initiatives that target their removal. This is a short-sighted approach that only harms urban household food access (Giroux et al., 2020). An alternative approach would be for national and local governments to treat street vendors and other small, local retailers as crucial actors within the local food retailer environment. Evidence for this as a useful approach exists. In Liberia, for example, street vendors and the Monrovia City Corporation have agreed to a legal understanding that normalizes street vending and allows street vendors to operate in designated areas without harassment (Reed & Bird, 2019). Nothing like this currently exists in Zambia, but it does provide an example of an approach to consider moving forward.

Transforming the food systems of smaller urban areas in SSA also extends to re-examining the role of traditional markets. We find the relationship between households and traditional markets is the result of differences in both the number and placement of traditional markets. Traditional markets provide food directly to households and also act as wholesalers to street vendors (Battersby, 2019; Giroux et al., 2020). In this capacity, traditional markets play a central role in the food distribution network, both in terms of bringing food from farmers into the city and then in terms of distributing food to street vendors and consumers. Because traditional markets have a central position within the food distribution system of smaller urban areas, including them in plans to transform smaller urban areas is critical and can have implications for food access among the poorest households through street vendors.

Conclusion

Mumbwa and Monze, like other urban areas included in this book, represent important sites for evaluating how food systems of smaller urban areas are transforming. Consumer retail dynamics and food access are changing as a result of rapid population growth and spatial extensification. While street vendors are critical for low-income households, characterizing food access or food security in terms of unidimensional patterns of household purchasing misrepresents the actual food purchasing behaviour of these households, which is related not only to economic resources but also to spatial location. Developing urban policy that promotes a mix of retailers, thus improving economic and physical access to food across socio-economic class, will become increasingly critical as secondary and tertiary urban areas continue to grow.

References

Abrahams, C. (2010). Transforming the region: Supermarkets and the local food economy. African Affairs, 109(434), 115–134.

AGRA. (2020). Feeding Africa’s cities: Opportunities, challenges, and policies for linking African farmers with growing urban food markets (AGRA Issue No. 8). Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa.

Bank of Zambia. (2019). National Statistics. Bank of Zambia. https://www.boz.zm/statistics.htm.

Battersby, J. (2017). Food system transformation in the absence of food system planning: The case of supermarket and shopping mall retail expansion in Cape Town, South Africa. Built Environment, 43(3), 417–430.

Battersby, J. (2019). The food desert as a concept and policy tool in African cities: an opportunity and a risk. Sustainability: Science Practice and Policy, 11(2), 458.

Battersby, J., & Crush, J. (2014). Africa’s urban food deserts. Urban Forum, 25(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-014-9225-5

Battersby, J., & Haysom, G. (2018). Linking urban food security, urban food systems, poverty, and urbanisation. In J. Battersby & V. Watson (Eds.), Urban food systems, governance, and poverty in African Cities (pp. 56–67). Routledge.

Battersby, J., & Watson, V. (2018). Addressing food security in African cities. Nature Sustainability, 1(4), 153–155.

Blekking, J., Waldman, K., Tuholske, C., & Evans, T. (2020). Formal/informal employment and urban food security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Applied Geography, 114, 102131.

Caesar, M., & Crush, J. (2016). Urban food deserts and climate change in Africa’s hungry cities (HCP Discussion Paper No. 3). Hungry Cities Partnership.

Chimoyi, L., & Musenge, E. (2014). Spatial analysis of factors associated with HIV infection among young people in Uganda, 2011. BMC Public Health, 14, 555.

Coates, J., Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2007). Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator Guide (Version 3). FHI 360/FANTA.

Cobbinah, P., & Amoako, C. (2012). Urban sprawl and the loss of peri-urban land in Kumasi, Ghana. International Journal of Social and Human Sciences, 6(388), e397.

Cohen, B. (2006). Urbanization in developing countries: Current trends, future projections, and key challenges for sustainability. Technology in Society, 28(1–2), 63–80.

Cohen, M., & Garrett, J. (2010). The food price crisis and urban food (in) security. Environment and Urbanization, 22(2), 467–482.

Crush, J., & Frayne, B. (2010). The invisible crisis: Urban food security in Southern Africa (Urban Food Security Series No. 1). African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN).

Davies, J., Hannah, C., Guido, Z., Zimmer, A., McCann, L., Battersby, J., & Evans, T. (2020). Barriers to urban agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa. Food Policy, 1, 101999.

Demmler, K., Klasen, S., Nzuma, J., & Qaim, M. (2017). Supermarket purchase contributes to nutrition-related non-communicable diseases in urban Kenya. PloS One, 12(9), e0185148.

Giroux, S., Blekking, J., Waldman, K., Resnick, D., & Fobi, D. (2020). Informal vendors and food systems planning in an emerging African city, Food Policy, 1, 101997.

Haysom, G., & Tawodzera, G. (2018). ‘Measurement drives diagnosis and response’: Gaps in transferring food security assessment to the urban scale. Food Policy, 74, 117–125.

Jere, J. (2020, June 26). Choppies to open five stores. Zambia National Broadcasting Corporation.

Montello, D., & Sutton, P. (2006). An introduction to scientific research methods in geography. SAGE Publications.

Nagendra, H., Bai, X., Brondizio, E., & Lwasa, S. (2018). The urban south and the predicament of global sustainability. Nature Sustainability, 1(7), 341–349.

Peyton, S., Moseley, W., & Battersby, J. (2015). Implications of supermarket expansion on urban food security in Cape Town, South Africa. African Geographical Review, 34(1), 36–54.

Pothukuchi, K., & Kaufman, J. (1999). Placing the food system on the urban agenda: The role of municipal institutions in food systems planning. Agriculture and Human Values, 16(2), 213–224.

Ravallion, M. (2007). Urban poverty. Finance and Development, 44(3), 15–17.

Reardon, T., & Zilberman, D. (2018). Climate smart food supply chains in developing countries in an era of rapid dual change in agrifood systems and the climate. In L. Lipper, N. McCarthy, D. Zilberman, S. Asfaw, & G. Branca (Eds.), Climate smart agriculture (pp. 335–351). Springer.

Reed, S., & Bird, M. (2019). Liberia’s street vendors pioneer new approach with city officials. WIEGO. Street Vendors and Public Space Report.

Sedda, L., Vilela, A., Aguiar, E., Gaspar, C., Gonçalves, A., Olmo, R., Silva, A., de Cássia da Silveira, L., Eiras, Á., Drumond, B., Kroon, E., & Marques, J. (2018). The spatial and temporal scales of local dengue virus transmission in natural settings: A retrospective analysis. Parasites and Vectors, 11(1), 79.

Seto, K., & Ramankutty, N. (2016). Hidden linkages between urbanization and food systems. Science, 352(6288), 943–945.

Skinner, C. (2018). Contributing yet excluded? Informal food retail in African cities. In J. Battersby & V. Watson (Eds.), Urban food systems governance and poverty in African Cities (pp. 104–115). Routledge.

Tefft, J., Jonasova, M., Adjao, R., & Morgan, A. (2017). Food systems for an Urbanizing World: Knowledge product (Working Paper No. 122014). World Bank Group.

Tuholske, C., Andam, K., Blekking, J., Evans, T., & Caylor, K. (2020). Comparing measures of urban food security in Accra, Ghana. Food Security, 12, 417–431.

UN-DESA. (2018). World Urbanization Prospects 2018.

Wanyama, R., Gödecke, T., Chege, C., & Qaim, M. (2019). How important are supermarkets for the diets of the urban poor in Africa? Food Security, 11(6), 1339–1353.

Zimmer, A., Guido, Z., Tuholske, C., Pakalniskis, A., Lopus, S., Caylor, K., & Evans, T. (2020). Dynamics of population growth in secondary cities across southern Africa. Landscape Ecology, 35(11), 2501–2516.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Blekking, J., Giroux, S., Waldman, K., Evans, T. (2023). Spatial Characteristics of Urban Food Systems and Food Retailers in Smaller Urban Areas. In: Riley, L., Crush, J. (eds) Transforming Urban Food Systems in Secondary Cities in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93072-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93072-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-93071-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-93072-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)