Abstract

International remittances are a major source of income for many low and middle-income countries. As remittances are sent directly to families and friends living at the place of origin, they have a significant impact on alleviating poverty. The literature on remittances suggests that most remittance-receiving households in urban areas use a major portion of the remitted income for food purchase–indicating a close relationship between remittances and food security. However, understanding of how remittances are related to urban food security is still limited. More specifically, what is the role of remittances in overcoming food insecurity both directly (as an additional means available to access food), and indirectly (as a source of investment for income-generating activities)? This chapter explores these relationships between migrant remittances and household food security in the secondary city of Mzuzu, Malawi, based on semi-structured interviews with migrant households, returnee migrants and key informants.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Food insecurity is a growing concern, in particular among the urban poor residing in secondary African cities (Battersby & Watson, 2019; Frayne et al., 2010; Mackay, 2019). The ability to access food in an urban context largely depends on the availability of cash income. The cash-based nature of the urban economy requires urban households to depend mostly on the market for accessing food and other basic necessities (Kimani-Murage et al., 2014; Tacoli, 2017). As such, people living in poor urban conditions with precarious income streams are particularly vulnerable to fluctuations in the price of food and related market shocks (Mohiddin et al., 2012). In Malawi, studies have documented that the price of maize reaches its highest point at the end of the lean season, in February, and that income shocks due to this price increase hit the poor hard, especially low-income urban dwellers (Harttgen et al., 2016; Sassi, 2015). Urban households with irregular income are more likely to be food insecure, which means that remittances received by migrant-sending households contribute to income stability and food security. They are the added source of income that can be used for meeting day-to-day needs and planning for future income security through investments. Most remittance-receiving households in low-income urban areas use a large proportion of the remitted income for food (Crush, 2013). However, research on migrant remittances and their implications for household food security and economic stability in the long term is crucial but very little explored (Choithani, 2017; Crush, 2013; Crush & Caesar, 2017).

This chapter uses the New Economics of Labor Migration (NELM) approach to explore the linkages between migrant remittances and household food insecurity in the sending community. The NELM approach is based on three main assumptions: relative deprivation, investment and insurance (Atuoye et al., 2017; Taylor & Taylor, 1999). Due to relative deprivation, households make migration decisions to improve household welfare through remittances (Stark, 1991; Taylor & Taylor, 1999). Similarly, remittances can be the source of investment in income-generating activities to expand household income streams; likewise, remittances can act as insurance in times of crisis or food price hikes (Atuoye et al., 2017; King & Collyer, 2016). The NELM approach is considered most relevant to study migration from low-income households because it uses qualitative interviews and household surveys and positions households as the central unit of research (Castles, 2009; de Haas, 2010). This approach facilitates an assessment of the degree to which remittances help migrant households to have continuous access to food without disruption, even in crisis situations.

Context of Malawians Migrating in Southern Africa

The history of international labor migration in the African continent dates back to the European colonial period, when the mining and farming industries established by Europeans required cheap labor from across the continent (Long & Crisp, 2011). Malawi (then Nyasaland), specifically Northern Malawi, has a long history of labor migration; most of its migrant workers traveled to South Africa to work in the mines through formal mechanisms (Ndegwa, 2015; Oucho, 1995). The formal migration of Malawians started in the late nineteenth century, coming to an end in the late twentieth century (Chirwa, 1997). In the early decades of the formal migration process, the migration was deeply rooted. The labor migration of men was sometimes even characterized as a major export of the country, as in an article published in the early 1940s, which noted that “the chief export of Nyasaland in the past fifty years has been men” (Read, 1943, p. 606). Since then, labor migration to the Southern African Development Community (SADC) countries and beyond has been the tradition in Malawian communities (Ndegwa, 2015; Oucho, 1995). Within SADC, South Africa is the major destination of labor migration from Malawi and is dominated by undocumented and informal workers, especially in domestic work and informal businesses (Banda, 2019).

The World Bank estimates that Malawians sent about US$181 million in 2018 to their households back home, which was much higher than the US$800,000 remitted in 2000 (World Bank, 2020). Similarly, remittances as a share of GDP rose from 0.065% in 1994 to 2.57% in 2018 (World Bank, 2020). This figure is low when compared with other remittance-receiving low- and lower-middle-income African countries such as Nigeria, Kenya, Mali and Zimbabwe (Ratha, 2021). However, remittances carry great importance in the livelihoods of the receiving households, as the transfer reaches directly to the household level. These statistics also hide much of the informal remittances and the remittances of goods.

Methodology

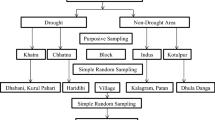

This research mainly employs qualitative methods based on the data collected at the household level. It focuses on the households living in informal settlements of Mzuzu that have at least one family member working in neighboring SADC countries. A combination of purposive and snowball sampling was applied to select migrant households and key informants. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with the migrants’ household representatives/heads to have a nuanced understanding of peoples’ lived experiences. A total of 42 migrant household representatives/heads and 37 key informants from different sectors/organizations working with migrant communities or having expertise in the migration and development and food security issues were also interviewed. Out of 42 migrant households, 41 had at least one family member who had migrated to South Africa—including three overlapping households that had an additional family member who had migrated to Tanzania, Zambia or Zimbabwe as well. The remaining one household had a member working in Tanzania only. Furthermore, to better understand the food security situation of migrant-sending households, the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) and Months of Adequate Household Food Provisioning (MAHFP) indicators were also captured. The HFIAS captures the household access to food in the previous four weeks, based on nine indicators from which Household Food Insecurity Access Prevalence (HFIAP) is calculated (Coates et al., 2007). The HFIAP categorizes food access components into four categories: 1 = food secure; 2 = mildly food insecure; 3 = moderately food insecure; and 4 = severely food insecure (Coates et al., 2007). The household food security status presented in the following sections refer to HFIAP. The MAHFP captures the status of the household food supply in the past 12 months (Bilinsky & Swindale, 2010). The household food supply status mentioned in the following sections refer to MAHFP.

The data were analyzed using the general inductive approach: finding the core meaning in the text; identifying themes most relevant to research objectives; and description of the most important themes (Thomas, 2006). NVivo 12 software was used to help with coding. The final step included the interpretation of the entire analysis (Creswell et al., 2003). The qualitative methodology revealed many nuanced perceptions of the effect of remittances on individuals’ experiences of food insecurity. These perceptions fall into the four topics discussed in the following sections: remittances invested in maize production; the consequences of lost remittances; the improvement of dietary quality with remittances; and how remittances create stability. The discussion of these topics is followed by reflections on the findings through a NELM analysis.

Remittances Support Maize Production

In the Malawian context, having enough stock of maize at home is considered the hallmark of food security (Kerr, 2014; Smale, 1995). A 2017 household food security survey found that one in three surveyed households in Mzuzu cultivates maize, which was by far the most widely cultivated crop (Riley et al., 2018). Many urban dwellers (about 38%) were involved in urban agriculture: about 20% were engaged in livestock rearing, and about one-third of households cultivated crops at rural farms (Riley et al., 2018). Interestingly, the survey found that households involved in farming in the rural and urban areas had better food security status and lived poverty index (Riley et al., 2018). About 37% of respondents who did not grow food cited lack of access to agricultural inputs as a barrier (Riley et al., 2018). Residents of the informal settlements in Mzuzu were also found to engage in cultivating maize, growing vegetables and rearing poultry and pigs.

These survey findings aligned with the rate of urban agriculture in this qualitative study. Out of 42 migrant households interviewed, 19 reported using remittances for farming, mainly for buying fertilizer and hiring farm workers (Table 17.1). When they could not cultivate, they would generally receive remittances to buy maize. In responding to a question about the importance of remittances in her household’s access to food, the participant, a widow in her late sixties who was living with a granddaughter, observed:

At first, it was hard for me to buy food. But now they send money each and every month for me to buy food. (Before) I wouldn’t even afford to buy fertilizer. Of course, this year I didn’t cultivate maize, but they have already started sending money for me to buy maize at the market. So, I don’t have food problems right now (Interview 8, June 30, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

The respondent had three household members working in South Africa. Her household was food secure and had a food supply for 12 months. She reported that the rental income of MWK40,000 (US$56) from two houses built using remittances, and the monthly transfers of between MWK30,000 and 70,000 (US$43–98) received from her three migrant family members made it easier to run her household of two.Footnote 1 While answering the importance of remittances in her livelihood, she mentioned living an easy life as she was having bread and tea for breakfast and did not have to worry about lunch and dinner. Her case indicates that the extended sources of income as a result of direct investment of remittances in building houses, along with regular remittance support and a small family, helped in having better access to food.

Similarly, a male participant in his mid-twenties had experienced improved access to food because of the regular remittance support from his father working in South Africa. His household was food secure and had adequate food supply for 11 months. When comparing the situation before and after migration, he observed, “[Before] you know it was possible that maybe some other days you could have maize flour to cook nsima, but you don’t have money to buy relish. But now we are able to find everything for our meal” (Interview 6, June 26, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi). His family was receiving monthly remittances of between MWK70,000 and 100,000. He reported using remittances to buy fertilizer as well.

Remittances have improved households’ access to farm inputs, specifically chemical fertilizer. Many respondents stated that the use of chemical fertilizer is very important for a good harvest; however, they could not afford fertilizer without remittances. The average retail fertilizer price in the country remained around MWK20,113 in 2018 (Africa Fertilizer n.d.). The price is very high when compared to the minimum wage rate, which remained at MWK962 per day in 2018 (MWK28,860 per month) (WageIndicator, n.d.). Moreover, some migrant households were also using remittances for hiring agricultural pieceworkers—locally known as ganyu. A female respondent in her early seventies put the importance of remittances this way: “At first, we were buying maize at the market, but now we have our own maize, and we use remittances to buy fertilizer and pay agricultural expenses. … We buy six bags of fertilizer each year using remittances” (Interview 39, August 10, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi). Her family had been cultivating for over a decade on borrowed land in Ekwendeni, a small town situated 20 kilometers north of Mzuzu. Her household was food secure and did not face any shortages of supply over the previous 12 months.

These narratives support the conclusion that remittance-receiving households, having remittances as an additional source of income, experienced increased access to food as these households used remittances to buy not only food, but also farm inputs for a better yield. Such findings also indicate that agriculture is still a livelihood strategy for many low-income households. The finding may be indicative of the peri-urban nature of Mzuzu—a city that shares common characteristics with other cities of sub-Saharan Africa, such as the challenges of urban poverty, rapid urbanization, clean drinking water, sanitation and health facilities—where a significant number of households still depend on agriculture to support their livelihood (Githira et al., 2020; Kita, 2017; Riley et al., 2018). Such observations further support the importance of remittances for low-income urban households in their struggle to achieve food security.

Without Remittances, Food Insecurity Worsens

For most migrant households, the frequency and the volume of remittances ensured improvements in their access to food even when they were faced with increasing food prices. However, some households with zero or nominal remittances from their family members had to face more challenges in accessing food. An example is a case of a female respondent in her mid-fifties. She took a loan of MWK60,000 to support her son for passport and transport. He went to South Africa in 2014. Instead, the burden of repaying the loan deteriorated her household’s ability to access food. While responding to her present situation regarding food access in comparison to the situation before 2014, she said:

There is a change, because, at first, the food at the house was just okay, but because I borrowed some money to send this boy [the migrant] for transport, and now I am still paying back the money. The way I am buying food now and the way I was buying at first is different. Now, I am struggling to buy food because the other money is being used to pay back the loans. (Interview 3, June 20, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi)

Her household was severely food insecure. Likewise, the household had food supply for only seven months. For similar households, the added burden of paying back the loan and lack of support from the migrant could make households vulnerable to food insecurity. To this end, a female respondent in her late sixties, who had a migrant son in South Africa, raised two points. First, she did not see any significant difference in her food security situation from the nominal remittance of MWK20,000 (US$28) she had received from her son in the previous 12 months. Second, increasing food prices were the main problem for her family’s restricted ability to access adequate food. Her household had a severe food insecurity scale and had access to sufficient food to meet her household needs for only seven months. While responding to the reason for the inadequate supply for the months from August to December, she said, “The food we get [from the farm] is not enough to take us from January to December,” indicating the main staple food they produced (maize) was not enough to feed the family for the whole year (Interview 32, July 31, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

The cases of migrant households such as those mentioned by the respondents in interviews 3 and 32 may be exceptional. However, even the migrant households that are solely dependent on remittances for food access may fall into the critical food insecurity situation once they stop receiving support from their migrant family member(s). In the Malawian context, a study on the effects of household income composition and occupational mobility on household welfare and poverty conducted between 2010 and 2013 found that diversified income sources result in improved household welfare in the urban areas (Benfica et al., 2018). Therefore, motivating and providing necessary support to migrant households to engage in income-generating activities that ensure long-term food security to the migrant households is essential. A similar observation was made by Atuoye et al. (2017) in their study in Ghana. The authors found that remittances were not enough to make households fully food secure and hence suggested developing an alternative livelihood strategy through the promotion of small enterprises and self-employment activities.

Remittances of Food and Money Support Healthier Diets

This study found that remittances support households’ access to healthier diets. Some households were able to add nutritious food to their daily dietary intake due to the remittances of food and money. Such was the experience of a female respondent in her mid-twenties whose husband had been working in South Africa since 2014. She was living with her three-year-old daughter in a grass-thatched house in one of the informal settlements of Mzuzu and did not have any source of income except remittances. While replying to a question about the changes in her ability to access food, she said, “Now, we eat a good diet. We manage to buy a tray of eggs and buy cooking oil. Before, I couldn’t manage that” (Interview 16, July 7, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi). However, her household was mildly food insecure as she couldn’t afford to eat her desired food in the last two weeks due to the lack of resources; she received remittances just four days before the day of the interview. For her household, the time immediately before receiving remittances was critical to access desired food. However, she experienced a significant improvement in her household’s overall access to food.

The food packages sent by migrants also carry great significance in improving household food security. Some migrant households received food packages that lasted for many months. Generally, migrants send cooking oil, sugar and Cremora (milk powder) from South Africa in December for the year-end festive season. In another interview, a female respondent in her mid-sixties, who had two family members in South Africa, said:

Milk, sugar, soap, body oil, cooking oil—like those things I received in December 2017 and they ended last month [June 2018]. He [migrant son] sends those once a year…. We can say it is more than MWK50,000 [in monetary value]. Because these things are cheap in South Africa but if you buy here, they cost more. He tells me that “if I send you money to buy groceries there, means it’s a lot of money. So it’s better I should just send them from here.” (Interview 17, July 7, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi)

Interestingly, some households that received such packages multiple times a year mostly did not need to buy those items in Mzuzu. For example, another respondent, a divorced woman in her mid-forties, reported receiving food items such as cooking oil and sugar three to four times a year. When responding to a question about whether her household needs to buy those items at the local market, she said, “Most of the times these things are sufficient to meet the household requirements” (Interview 18, July 16, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi). Another female respondent in her late fifties also reported receiving food packages and groceries (specifically, soap, oil and milk) four times a year (Interview 41, August 17, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi). Moreover, the above excerpt from interview 17 indicates that migrants prefer to send food packages as the items are cheaper in South Africa. Furthermore, it may also minimize the chances of remittances being used for other, less important, things by the family member. Overall, remittances sent in food and money helped remittance-receiving households with improved access to food.

Overreliance on remittances can create its own vulnerability. Households that lack sources of income beyond remittances have to compromise their food intake if they fail to receive support on time. The case of a respondent who was living with a three-year-old daughter (interview 16) suggests the need to have an alternative source of income in addition to remittances to better ensure household food security. Studies in South African cities have also shown that households with irregular income are more likely to be food insecure (Frayne & McCordic, 2015). Remittance-dependent households going through such situations are more likely in a migration system that is dominated by low-skilled and irregular migration, which ultimately determines the volume and frequency of support from migrants to their families back home.

Remittances Create Stability

Another improvement found due to remittances was fully or partially reduced incidence of skipping meals. Skipping meals is one of the coping strategies practiced by many poor households across Africa (Ngidi & Hendriks, 2014; Stella et al., 2015; Tsegaye et al., 2018). This coping strategy was also adopted by many migrant households in Mzuzu in difficult times. The respondent of another migrant household, a male in his late forties, was the area chief of one of the settlements chosen for the study. He had a son in South Africa who was sending support to him every two to three months. While responding to the changes in his family’s access to food, he said:

There is a great change right now…. Earlier, I was using the money I received as a pension but at present, as he went there and [is] sending something, that something is helping us. We are buying extra food and the other things which were lacking before. … First, we didn’t have breakfast and rice. But now we do [have] breakfast and also eat rice for breakfast. Now, we use rice for breakfast every day. In most cases, we use rice with tea instead of buying bread. Before we just possibly ate porridge, using common flour and sometimes without sugar. Now we don’t have that problem (Interview 10, July 3, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

His household belonged to the food secure category. In his case, the respondent had a regular pension income, he was also working part-time, and the family had remittance support from the son. These diverse income sources improved the household’s food stability enough that family members no longer had to skip meals.

A similar improvement was experienced by another respondent, a male in his mid-twenties, but in reduced incidences of skipping breakfast. His household decided to send a second family member, the elder daughter, to South Africa, as they could not receive enough support from the first migrant (a younger son). When the daughter started sending remittances, the household noticed a considerable improvement in its access to food. When responding to a question about the changes observed due to the availability of remittance income, the respondent replied:

At least now we are better off because if we talk about the most difficult times, we used to stay a whole week without breakfast, even a month, but now we can only stay without it maybe for two days only. … Before, we would sometimes just mix Super Dip with water and eat. [Super Dip is one of many types of juice powder that is mixed with lots of water. People often drink it to deal with hunger. It costs about 50 to 60 kwacha per pack.] (Interview 35, August 8, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

Sometimes, even if remittances were not received on time, having remittances as a support mechanism gave migrant households enough privilege to borrow money. A female respondent in her early fifties had experienced improved confidence to borrow money during difficult times. For instance, when there was no maize at home or when there was no money to bring maize to the maize mill for processing, she was sure that she could pay back a loan, knowing that she would receive remittances from her migrant son. She said:

There is a big difference because, at first, I was only relying on fetching firewood. As you can see there is raining outside, [and] when it rains, I couldn’t go and fetch firewood. It means I would stay maybe three, four days without food. But right now, because I receive remittances, even though they [migrants] skip some months, I do keep the money to buy maize. If I don’t have money to go to the maize mill, I will borrow some from someone because I have a hope that I receive remittances later to cover the expenses (Interview 23, July 20, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

Another effect of remittances on ensuring food stability was households’ improved ability to buy food in bulk. In Malawi, food price generally goes down during the harvest season and up in the rainy season, and such a trend has been recurring for years (Sassi, 2015). So urban dwellers having enough resources prefer to buy during the harvest season, which starts in April and continues until June. For example, the participant who was living with a three-year-old daughter and had remittances as only the source of income observed her increased ability to buy maize for a whole year because of remittances. In her words:

I buy food [maize] for a whole year now. Before, we were buying just for a month. Back then, we didn’t have money to buy maize for the whole year. But now, we manage to buy. In the village, the price of the maize remains the same throughout the year. But here, you find maize cheap in the harvest season and high during the rainy season. So we buy for a whole year [during the harvest season] (Interview 16, July 7, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

This was similar to the experience of another respondent, a female in her mid-thirties whose husband was working in South Africa. She had a timber shop at the local Vigwagwa Market. When responding to a question about the changes in her household’s ability to access food, she said:

There is a difference because, at first, we were buying most of the things daily. But now we buy groceries, maybe some other groceries which can take us for many days. For maize, we buy it every month but ... when the month of June comes, we buy maize for a long period of time ... because the maize price goes high in November-December and the rainy season (Interview 34, August 8, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

Another participant in her early forties also observed the improved capacity to buy in large quantities due to remittances. She said:

Right now, because we don’t usually go to the market, when we want to buy maize, we buy it for some months. We go to the market for relish only. Before, we used to go to the market and buy a few kilograms of flour, not maize. But now we buy many bags of maize that lasts for months (Interview 13, July 5, 2018, Mzuzu, Malawi).

While visiting informal food markets in Mzuzu, anyone can easily observe vendors selling food items such as rice, flour, beans, vegetables and oil in the lowest quantities or units possible. People from low-income categories tend to buy in small quantities and eventually pay more than those buying in large quantities. Furthermore, recent studies in Malawi have also documented that poor urban dwellers are vulnerable to food price fluctuations (Harttgen et al., 2016; Sassi, 2015). As such, buying maize during the harvest season not only saves money but also ensures enough supply of food for months. The excerpts presented above support the notion that households experience better food stability through an improved supply of food due to remittances.

NELM Theory and the Linkages Between Migrant Remittances and Household Food Security

The results indicate a complex association between migrant remittances and household food security. It is intertwined with many factors. The major ones are the informal nature of migration, which determines the volume and frequency of remittance support, and recurring food price volatility, which makes the urban poor vulnerable to food insecurity. Interestingly, the migration of a family member is one of the coping strategies adopted by many low-income households to overcome household food insecurity (Derribew, 2013; Khatri-Chetri & Maharjan, 2006). The findings of this study show that remittances helped improve the household food security situation of many migrant households; however, the support was not enough to completely lift them out of the condition of food insecurity.

The NELM approach facilitated the assessment of this study. The approach postulates that migratory decisions are made to increase household welfare through diversified income sources, to make investments in income-generating activities and to support households in times of shocks (Stark, 1991). The migrant households used remittances directly to access food and indirectly to make investments in agriculture—mainly for buying fertilizer and hiring farm laborers. The remittance investments in agriculture were the economic activity that the migrant households chose to improve their household welfare, as suggested by the NELM (de Haas et al., 2020). Such investment ultimately helped migrant households with improved food supply as well as income. Remittances were also found as insurance, a risk-aversion mechanism for households during difficult times (King & Collyer, 2016), as in the case of the migrant household in interview 23, where households could rely on remittances when suffering from reduced income sources due to economic and environmental shocks.

The findings indicate that remittances lead to only short-term improvements in access to food, unless remittances are used to expand household income sources. On the other hand, remittance investment in entrepreneurial activities is critical in the migration system, which is dominated by low-skilled and irregular migrancy. As such, this investigation suggests that achieving all four pillars of food security—availability, access, utilization and stability—will remain a distant prospect without appropriate policy interventions in the context of Mzuzu, where people are living with precarious income sources and have to go through recurring food price shocks. The NELM theory is helpful in addressing the situation, as it stresses creating a favorable investment environment to leverage remittance investments through economic policy reforms (Taylor & Taylor, 1999). Empirical evidence from Atuoye et al.’s (2017) recent study in Ghana also supports this conclusion. Their study documented the fact that remittances alone are not enough to make households completely food secure; hence, they suggested developing an alternative livelihood strategy through the promotion of small enterprises and self-employment activities.

Finally, the findings of this chapter should be understood in the context of international labor migration from informal settlements in Mzuzu, Malawi. These findings are also relevant in understanding the situation of migration and household food security in the context of growing urban poverty in the rapidly urbanizing cities of the developing world.

Notes

- 1.

In mid-2018, the exchange rate was approximately US$1 = MWK715.

References

Africa Fertilizer. (n.d.). Retail fertilizer prices, https://africafertilizer.org/local-prices/#tab-id-2.

Atuoye, K., Kuuire, V., Kangmennaang, J., Antabe, R., & Luginaah, I. (2017). Residential remittances and food security in the Upper West Region of Ghana. International Migration, 55(4), 18–34.

Banda, H. (2019). The dynamics of labour migration from Northern Malawi to South Africa since 1974. PhD thesis, Faculty of Humanities, University of Witwatersrand

Battersby, J., & Watson, V. (Eds.). (2019). Urban food systems governance and poverty in African cities (1st ed.). Routledge.

Benfica, R., Squarcina, M., & De La Fuente, A. (2018). Structural transformation and poverty in Malawi. International Fund for Agricultural Development. IFAD Research Series No. 25

Bilinsky, P. and Swindale, A. (2010). Months of Adequate Household Food Provisioning (MAHFP) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide (version 4). FHI 360/FANTA

Castles, S. (2009). Development and migration or migration and development: What comes first? Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 18(4), 441–471.

Chirwa, W. (1997). “No TEBA …Forget TEBA”: The plight of Malawian ex-migrant workers to South Africa, 1988–1994. International Migration Review, 31(3), 628–654.

Choithani, C. (2017). Understanding the linkages between migration and household food security in India. Geographical Research, 55(2), 192–205.

Coates, J., Swindale, A., & Bilinsky, P. (2007). Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household food access: Indicator guide (version 3). FHI 360/FANTA

Creswell, J. W., Plano Clark, V., Gutmann, M., & Hanson, W. (2003). Advanced mixed methods design. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), SAGE handbook of mixed method in social and behavioral research (pp. 209–240). Sage.

Crush, J. (2013). Linking food security, migration and development. International Migration, 51(5), 61–75.

Crush, J., & Caesar, M. (2017). Introduction: Cultivating the migration-food security nexus. International Migration, 55(4), 10–17.

de Haas, H. (2010). Migration and development: A theoretical perspective. International Migration Review, 44(1), 227–264.

de Haas, H., Castles, S., & Miller, M. (2020). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world (6th ed.). Guilford Press.

Derribew, A. (2013). An assessment of coping strategies for drought induced food shortages in Fedis District, East Hararghe Zone, Ethiopia. International Journal of Science and Research, 4(1), 284–289.

Frayne, B., & McCordic, C. (2015). Planning for food secure cities: Measuring the influence of infrastructure and income on household food security in Southern African cities. Geoforum, 65, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.06.025

Frayne, B., Pendleton, W., Crush, J., Acquah, B., Battersby-Lennard, J., Bras, E., Chiweza, A., Dlamini, T., Fincham, R., Kroll, F., Leducka, C., Mosha, A., Mulenga, C., Mvula, P., Pomuti, A., Raimundo, I., Rudolph, M., Ruysenaa, Sh., Simelane, N., Tevera, D., Tsoka, M., Tawodzera, G., & Zanamwe, L. (2010). The state of urban food insecurity in Southern Africa. African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN). Urban Food Security Series No. 02

Githira, D., Wakibi, S., Njuguna, I., Rae, G., Wandera, S., & Ndirangu, J. (2020). Analysis of multiple deprivations in secondary cities in sub-Saharan Africa, https://www.ittransport.co.uk/projects/analysis-of-multiple-deprivations-in-secondary-cities-in-sub-saharan-africa/

Harttgen, K., Klasen, S., & Rischke, R. (2016). Analyzing nutritional impacts of price and income related shocks in Malawi: Simulating household entitlements to food. Food Policy, 60(1), 31–43.

Kerr, R. (2014). Lost and found crops: Agrobiodiversity, indigenous knowledge and a feminist political ecology of Sorghum and Finger Millet in Northern Malawi. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104(3), 577–593.

Khatri-Chetri, A., & Maharjan, K. (2006). Food insecurity and coping strategies in rural areas of Nepal: A case study of Dailekh District in mid western development region. Journal of International Development and Cooperation, 12(2), 25–45.

Kimani-Murage, E., Schofield, L., Wekesah, F., Mohamed, S., Mberu, B., Ettarh, R., Egondi, T., Kyobutungi, C., & Ezeh, A. (2014). Vulnerability to food insecurity in urban slums: Experiences from Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Urban Health, 91(6), 1098–1113.

King, R., & Collyer, M. (2016). Migration and development framework and its links to integration. In B. Garcés-Mascareñas, & R. Penninx (Eds.), Integration processes and policies in Europe. IMISCOE Research Series (pp. 167–188). Springer

Kita, S. (2017). Urban vulnerability, disaster risk reduction and resettlement in Mzuzu city, Malawi. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22(1), 158–166.

Long, K., & Crisp, J. (2011). In Harm’s way: The irregular movement of migrants to Southern Africa from the Horn and Great Lakes Regions. UNHCR. Research Paper No. 200

Mackay, H. (2019). Food sources and access strategies in Ugandan secondary cities: An intersectional analysis. Environment and Urbanization, 31(2), 375–396.

Mohiddin, L., Phelps, L., & Walters, T. (2012). Urban malnutrition: A review of food security and nutrition among the urban poor. Nutrition Works, 8

Ndegwa, D. (2015). Migration in Malawi: A country profile 2014. International Organization for Migration. IOM Report

Ngidi, A., & Hendriks, S. (2014). Coping with food insecurity in rural South Africa: The case of Jozini, Kwazulu-Natal. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(25), 278–289.

Oucho, J. (1995). Emigration dynamics of Eastern African Countries. International Migration, 33(3–4), 391–467.

Ratha, D. (2021). Keep remittances flowing to Africa. In A. Ordu (Ed.), Foresight Africa 2021 (pp. 17–19). Brookings Institution.

Read, M. (1943). Migrant labor in Africa and its effects on tribal life. International Labour Review, 45(6), 605–631.

Riley, L., Chilanga, E., Zuze, L., & Joynt, A. (2018). Food security in Africa’s secondary cities: No. 1. Mzuzu, Malawi. African Food Security Urban Network (AFSUN). Urban Food Security Series No. 27

Sassi, M. (2015). The welfare cost of maize price volatility in Malawi. Bio-Based and Applied Economics, 4(1), 77–100.

Smale, M. (1995). “Maize is life”: Malawi’s delayed Green Revolution. World Development, 23(5), 819–831.

Stark, O. (1991). The migration of labor. Basil Blackwell.

Stella Wabwoba, M., Wanambacha Wakhungu, J., & Omuterema, S. (2015). Household food insecurity coping strategies in Bungoma County, Kenya. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences, 4(6), 713–716.

Tacoli, C. (2017). Food (in)security in rapidly urbanising, low-income contexts. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(12), 1554.

Taylor, E., & Taylor, J. (1999). The new economics of labour migration and the role of remittances in the migration process. International Migration, 37(1), 63–88.

Thomas, D. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246.

Tsegaye, A., Tariku, A., Worku, A., Abebe, S., Yitayal, M., Awoke, T., Alemu, K., & Biks, G. (2018) Reducing amount and frequency of meal as a major coping strategy for food insecurity. Archives of Public Health, 76(1), Article 56

WageIndicator. (n.d.). Minimum wages in Malawi with effect from 01–07–2017, https://wageindicator.org/salary/minimum-wage/malawi/archive-before-2019/minimum-wages-in-malawi-with-effect-from-01-07-2017

World Bank. (2020). Personal remittances, received (% of GDP)—Malawi, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.TRF.PWKR.DT.GD.ZS?locations=MW

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Dhakal, A. (2023). Migrant Remittances and Household Food Security in Mzuzu, Malawi. In: Riley, L., Crush, J. (eds) Transforming Urban Food Systems in Secondary Cities in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93072-1_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93072-1_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-93071-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-93072-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)