Abstract

Cancer has been a highly prevalent topic in the news media for some time and continues to be so with the rise and alleged promise of precision medicine. In this chapter, we present two empirical studies that explore how the news media frames issues related to cancer treatment and research.

Our two studies both find a striking lack of nuance and diversity in the framing. The media coverage has seemingly stagnated, with a framing of either tragic choices and patient stories, or the sensationalistic coverage of new cancer drugs and treatments. The news content is accepted as is without further challenging questions or objections. We consider why it is that these news framings remain unchallenged in this way.

We argue that we need a more sober approach to cancer in the news media, thus challenging the dominant framings that have characterized the media coverage of the topic of cancer over the last decade. The news media is one of the contributing instances, shaping the public discourse on cancer. However the answer as to why we see this complete lack of nuance cannot solely be studied with a media centred approach.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Opportunities and costs of cancer treatment are on the increase (WHO Technical report 2018). Opportunities are often framed as medical and costs as economic. This creates an imbalance between medical opportunities, economic realities and public expectations. Globally, national health expenditures have risen considerably in recent decades, with the US seeing an increase in its GDP healthcare spending from 5.2% in 1960 to 17.9% in 2017 – and is projected to reach 20% by the end of 2020 (CMS 2018). Concurrently, annual global oncology drug costs have exceeded 100 billion US dollars, and were projected to exceed 150 billion US dollars in 2020 (IMS Institute 2016). As prices on new cancerdrugs continue to rise, they claim an increasingly large proportion of health budgets – and are likely to do so at an increasing rate, as we face ageing populations more prone to cancer disease.

Following this development, the issue of cancer and cancer drugs holds a considerable presence in the newsmedia. The public interest on the issue has been especially persistent in recent years with the rise and alleged promise of precision medicine. National and global costs of cancer medicines affect entire populations of patients, and the issue of priority-setting in relation to expensive cancerdrugs has thus become a highly relevant and much-debated issue. As a result, in several countries there are ongoing debates in the public on medical priority-setting related to the introduction of new and expensive cancer drugs and treatments.

In both the public, political and medical discourse, a dominant frame of the issue of expensive cancer drugs is that of tragic choices, where suffering and death by cancer is considered an intolerable evil for the patients, while drug prices are considered intolerable to society as a whole (Fleck 2013). In the most polarised expressions of these controversies, as presented in hundreds of Norwegian newspaper articles, cancer patients and their representatives experience the situation as one of the government threatening their lives by denying them access to the newest and most costly drugs, over concerns for the public health budget. These polarised expressions, along with other expressions of similarly extreme framings, have become so typical of the debate that it seems to have stagnated, with a continuous reproduction of virtually the same positions. This suggested to us that there was a need for research on public media framings on the issue of priority-setting in relation to expensive cancerdrugs.

Further, the newsmedia devotes considerable attention to cancer research and what the future of cancer treatment will hold. Precision medicine has been particularly prevalent in the news, and it has been associated with great opportunities and high expectations. The portrayal of precision medicine often includes strong normative visions regarding future treatments. Adding to this, precision medicine is linked to strong optimism and is depicted in the news as the ultimate breakthrough in cancer research, leading the public to believe the cure of cancer is nearing – 40 years after President Nixon declared war on the disease (National Cancer Institute, National Cancer Act of 1971). When institutions and actors in society make important decisions regarding the direction of science and future research, it should be based on an informed and critical basis concerning the issue at hand. One of the media’s central roles is to provide a platform where such debates can take place and to separate information and facts from opinions and beliefs. This, therefore, raises questions concerning the possible implications such an optimistic and determined depiction of precision medicine might have for society, and calls for an exploration of how cancer research is framed in the public newsmedia.

In this chapter, we will briefly present two empirical studies of the Norwegian media debate. The first is a study by Mille Sofie Stenmarck, a medical doctor and PhD candidate, on the media debate and public discourse concerning expensive cancer drugs (Stenmarck et al. 2021). The second is by Irmelin Nilsen, who has a background in media studies, focusing broadly on the role of the media in today’s society. The studies were undertaken from 2017–2019 and they addressed news material on cancer spanning from 2013 to 2017. We focus on media as the central actor in presenting and providing information on precision oncology, thus holding a media centred perspective. These two studies, although performed separately, are well suited for a joint presentation as they highlight two different but important aspects of the field of cancer research. The first study explores the public discourse on the current issues surrounding modern cancer treatment, whilst the second study examines the scientific community’s conception of the future of cancer treatment – both in light of the framing these issues are presented with in the media.

We will display various frames but above all highlight how there is a striking lack of polyphony in the media debate, leaving out important views and stories from the public discourse. We will also present and discuss four unquestioned assumptions that we identified in the material, which we find highly questionable from the perspective of medical ethics, as well as from a social and political critique. We will subject these to critical analysis and discuss how the framing of cancer and cancer research in the news affects public understanding of those issues. Through this discussion, we aim to gain a better understanding of the structure of the debate on cancer and cancerdrugs, with the hope of moving thinking beyond that solely of tragic choices.

Framing Within the NewsMedia

Before presenting our studies, we will briefly introduce some basic understandings of the operations of the newsmedia and their use of frames, an understanding which underpins the following studies. The newsmedia serves the citizens with a certain worldview, and much of our understanding of certain topics is shaped by how the newsmedia chooses to present this. The central role of the media is to provide unbiased information, ensure that those in power do not abuse their power and ensure diversity, in the context that different views of society and political directions are visible in the public debate.Footnote 1 Adding to this, the press is institutionalized – meaning journalists and editors follow a specific set of established ideals, practices, and routines in their work (Eide 2011). For instance, the definition of what is regarded as a novelty, is constituted by a set of news criteria, or news values. More precisely, if an incident is close in time, space, and culture, and if the incident or issue was unexpected, unusual, and meaningful, these are considered characteristics that may qualify as a novelty, and noteworthy enough to report in the newsmedia (Galtung and Ruge 1965).

However, news value can be added by the journalist, and does not necessarily need to characterize the incident or issue in itself (Eide 2011). By doing this, journalists can add a specific framing. Framing is often understood as selecting one aspect of the issue and amplifying this to create a frame that the incident or issue is presented within (Entman 1993). In turn, this can affect how an issue is understood by the news consumer (Schudson 2003). The sources can also play a significant role in deciding how the issue is framed. If the sources have a clear agenda which they wish to present, they can present it in a way that fits the established news criteria. Gamson and Modigliani (1989) address that sources can use sensational words and phrases to lead the journalist to choose a specific framing of the issue. At the same time, journalists can use certain sources to amplify their own framing of the issue. Nevertheless, previous media studies have addressed the fact that the so-called political and societal elites and their views seem to dominate the news, and journalists often choose framings that support these views, rather than challenge them (Bennett et al. 2006).

Identifying Frames Within the Discourse on Priority-Setting and Cancer

As exploratory research suggested a clear lack of nuance in the Norwegian public discourse on priority-setting in relation to cancer and expensive cancerdrugs, we saw the need for an in-depth analysis of this debate and how it is framed within the public discourse. We wished to explore both how the issue itself is framed, and if there are central stories that remain untold. At a superficial glance, the discourse appeared un-nuanced and overly simplified, with an abundance of stories highlighting – rather coarsely – the tragedy that cancer entails, but with a simplistic presentation of both the realities of living with a cancer diagnosis, and of the realities, possibilities and constraints of cancer research. The issue of priority-setting and cancer appeared to be continually portrayed as one of tragic choices with the framings enhancing – or perhaps even creating – a dichotomy between winners and losers in the battle over budget allocation and scarce health resources. We therefore wished to gain an overview of the public discourse and the stories that are told within it – and to explore if there were missing aspects to this discourse, which, if brought to light, could perhaps challenge the persisting view that priority-setting in relation to cancer is always and indubitably an issue of tragic choices.

In order to study the framings within this debate, we applied framing theory. We used a methodological approach based on the work of Erving Goffman, who argued that frame analysis is a study of the cognitive organisation of experiences (Goffman 1974). He argued that we cannot understand the issues in front of us without consciously or subconsciously framing them in our minds, and that each and every issue we consider is consciously or subconsciously placed within a framework that makes it understandable to us. Through framing theory, one can identify the lenses through which we view society, and also identify the frames that are chosen for us in story-telling, and in the media. Framing theory thus allows us to consider not only what is said in the newsmedia, but also how it is said. Through applying this theory, we can thus also – importantly – begin to understand why it is said.

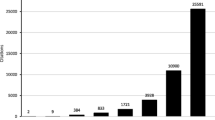

In order to identify frames in our material on the discourse on priority-setting and cancer, each article was structurally examined along the following four considerations: (1) what is the problem, (2) who are the actors, (3) where is the allocation of power, and (4) what sources have been used. In order to collect relevant data for our studies we used the Norwegian newspaper database Atekst. We included all articles published on the issue of priority-setting and cancer from the eight largest Norwegian national newspapers, spanning from January 1st 2013 to December 31st 2016. This provided us with a total of 439 newspaper articles. We chose the above-mentioned time frame due to the developments in the public debate on cancer and priority-setting, an issue that gained an increasingly large presence in the newsmedia around this time. This was largely due to a controversy surrounding the melanoma drug Ipilimumab, which took place in 2013. Ipilimumab is a particularly costly cancerdrug and at the time, the organ which considers the use of new drugs in the public healthcare system, the Decision-Making Forum (Beslutningsforum), recommended that the drug should not be made available in Norwegian public hospitals, due to an unfavourable cost-benefit analysis. This gave the issue considerable media attention, with a large number of newspaper stories featuring individual patients who would consequently be denied the new drug, and highlighting the tragedy and alleged inherent unfairness of this decision. Following considerable news coverage and a loud public outcry, the health minister in Norway at the time, Jonas Gahr Støre, chose to overrule Beslutningsforum’s recommendation and allow for the use of this drug in public hospitals. This kind of political intervention in the process of decision-making and distribution of health resources was unprecedented at the time. One could argue that this incident gave birth to a new wave of public engagement surrounding priority-setting in relation to cancer treatment in Norway, as it demonstrated that public and political uproar had the power to alter recommendations and decisions made by the existing, and well-established, framework for priority-setting. As the study was led in 2017, the data collection cut-off was the end of 2016.

The pervasive theme in the identification of the framings of these articles was a striking lack of nuance. Although we identified nine separate frames as the most common ones, in almost every frame the problem was the same – namely that of the suffering patient denied an expensive cancerdrugs, and the apparent injustice of these decisions. The constellation of actors was similarly unvaried, with the patient/doctor/patient organisation being pitched against the priority-setting system/health authorities/politicians. The allocation of power was determinedly placed with the system/authorities, whilst patients/doctors were presented as virtually powerless. And finally, the sources appeared to be surprisingly unvaried, mainly consisting of statements from patients, doctors or the Norwegian Cancer Society. Following a closer study of the articles, we gradually identified not only the lack of nuance of this discourse, but also what appeared to be four major assumptions underlying every newspaper article. These assumptions were so prevailing in the material that they arguably form the basis of the discourse itself. They read as follows:

-

1.

Cancer drugs are de facto expensive, and one does not and should not question why.

-

2.

These cancer drugs work, and there is no need to question the validity of this claim.

-

3.

Prolongment of life for a cancer patient is an absolute and unproblematic good, and any gained time – whatever shape or form that time has – is a blessing.

-

4.

Patients, and their doctors, own the truth about cancer and cancer drugs, and “outsider” views on these are irrelevant, or unwelcome.

Once we had identified these four assumptions, we were surprised by how very prevalent they were in the material. The adherence to these assumptions thus suggests that they are indeed four central premises that underlie the public discourse on cancer and cancerdrugs. Furthermore, our study of these articles covered a timespan from 2013 to 2016, yet there was very little evidence to suggest that the discourse went through any meaningful development during that time period. There did not seem to be any progression in either its structure or in its content, nor any real evolution to the arguments within it. It seems to us that there existed, purposefully or not, an apparent unwillingness to challenge these premises that underlie the discourse, and this suggested to us that the continued adherence to these premises is indeed a root cause to the stagnation of the discourse itself.

Precision Medicine as a Medical Revolution

While the first study mainly considered the dominant framings of the priority-setting debate around cancer and expensive cancer drugs, the second study considered how the future of cancer research is imagined by cancer researchers and other prominent actors in the field of cancer. In addition, we examined how research and scientific perspectives on cancer treatment is framed in the editorial news. Based upon a qualitative exploration, we examined the dominant framings of cancer research coverage in three national Norwegian newspapers: Aftenposten, Dagbladet and Verdens Gang. The reason for choosing these three papers is that they are three nationwide newspapers, thus covering and representing stories from the whole country, as well as being the three most read papers in the years of the study, namely 2016–2017 (Medienorge 2019). We wanted to focus on the papers that target the general public, hence we chose to not include news sources that were specifically targeted to people associated with the health field.

As the study commenced in 2018, we wanted to use the most recent material available. Adding to this, we also wanted to cover a fairly broad period. The material was thus gathered from Atekst in the period from January 1st 2016 to December 31st 2017, and the search resulted in 464 texts. This number was reduced to 53, to ensure that the material included only the texts that mentioned cancer research and cancerdrugs and excluding those that did not.

We applied a qualitative content analysis and studied expressions, opinions and argumentations that allowed us to identify different future imaginaries within the news content. The theoretical framework applied to the study was based on the analytical term sociotechnical imaginaries. This theoretical tradition argues that there exist strong collective visions of a desired societal, scientific and technological future (Jasanoff and Kim 2009, 2015). They are considered particular visions for a future that tends to be presented as optimistic and positive. These imaginaries can influence the choices made in research, and accordingly the future that is created based on these visions. In the field of cancer research, previous international literature has established that there exists a future vision on precision oncology in the Western society, and that this consists of strong normative aspects (Blasimme 2017; Blanchard and Strand 2017).

We wished to examine whether there existed strong future visions surrounding cancer research and treatments in the Norwegian media discourse – and if so, how they were articulated and argued for. In the material, we found that the vision of precision oncology is strongly present in the Norwegian media discourse. By exploring the material, which included both editorial and non-editorial news content (e.g. debates, chronicles, reader letters), we identified three variants of the sociotechnical imaginary concerning precision medicine. The three main visions and imaginaries which proved prominent, all related to precision medicine and the future of cancer treatments, were as follows:

-

1.

Precision medicine, particularly immunotherapy, will revolutionise cancer treatment.

-

2.

Artificial intelligence will make diagnosis and treatment more effective.

-

3.

The cancer-industry will become Norway’s next billion-dollar industry.

These three future visions, all tied to precision medicine, thus comprised (1) a scientific aspect, (2) a technological aspect, and (3) a socioeconomic aspect. In the first imaginary, immunotherapy was imagined as revolutionising cancer treatment by securing a targeted treatment for each and every patient. The second imaginary praised the use of emerging technologies, and how artificial intelligence and machine learning in particular were going to be used as a central part of future diagnostics and prognostics, and would make treatments more effective. The third and final imaginary revolved around harvesting the socioeconomical benefits of building a Norwegian cancer industry, and the idea that Norway will lead the way in the development of precision medicine. In addition, these visions were articulated as the only natural direction that the future of cancer research and treatment should move towards. These imaginaries were stated by oncologists, researchers and leading figures in the cancer industry, mainly through opinion pieces in non-editorial news content.Footnote 2

In this study, we also considered how the topic of cancer research was handled by journalists, and if the sociotechnical imaginaries identified were ever questioned or challenged. Through examining the editorial news content, we found that the news articles were characterised by the same future imaginaries as the actors in the field of cancer had stated in their own pieces. The news articles further tended to use words such as “revolution”, “miracle” and “breakthrough” when presenting new cancer research, particularly immunotherapy.

The prevalent frame that journalists used to cover cancer research was the sensation/information frame, identified through the journalists’ use of sensationalistic headlines and lead paragraphs, as well as the neutral and informational body text. Here, they usually cited a cancer researcher or an oncologist, and used almost exclusively only a handful of prominent actors in the field of cancer as their sources. By letting the same sources comment repeatedly, they both limit the diversity that the media should strive for, and also contribute to amplifying their opinions and views at the expense of others. Thus, few voices are shaping the framework and understanding of an entire field. The future vision on precision medicine, as outlined above, was prevalent throughout the timespan of the material and was not met with a single critical question by the journalists, and had no counter-visions to challenge it.

Further, our study shows that the editorial frames on cancer research is characterised by optimism concerning precision medicine. The analysis demonstrated that the news articles tend to favour research related to precision medicine, by referring to this research as continually producing highly promising breakthroughs in cancer research. We found exceptionally few texts that challenged this vision, and even fewer that presented an alternative future vision of cancer treatments and cancerdrugs. Thus, we found that journalists tended to frame cancer research in the same way as the actors in the field of cancer – arguably overly optimistic, and undeniably lacking in nuance. This demonstrates the lack of variety in the coverage of the cancer research in the news, both in terms of what research is referred to in the newsmedia, but also in how the research is presented – with an (overly) optimistic and deterministic framing. It also demonstrates that cancer researchers’ visions seem to be reproduced and reinforced by journalists and editors in the Norwegian newsmedia – lending these visions a validity they cannot always rightfully claim.

Discussion

The common and general findings from our studies are (1) the lack of nuance in the discourse on cancer and cancer drugs, and (2) the lack of variation in terms of how the issue of cancer and cancer research is covered in the newsmedia. This lack of nuance has in turn arguably led to a lack of progression in the discourse and public debate. We would argue this stagnation continues to hinder a true understanding of the issues of cancer disease, cancer treatment and cancer research amongst the general public, with an overly simplistic and un-nuanced presentation of what are arguably complex and ambiguous issues. Our most noteworthy findings are therefore the aspects that remain absent from the discourse.

In the following section, we wish to highlight and address some of these absent aspects, and further consider how and why the discourse has become what it is today. We thus hope to further challenge the adherence to the premises that underlie the discourse, and in doing so, to confront the notion that the issue of cancer and cancerdrugs must solely be an issue of tragic choices.

Why Have the Premises Remained Unchallenged?

Cancer treatment is one of the largest research fields in medicine, and cancerillness is increasingly common and thus also an increasingly relevant aspect of public health. Yet, as we have demonstrated, the discourse on these issues seems to have stagnated, remaining virtually unchanged both in form and substance throughout the years we have studied it. Thus, despite the size and alleged promise of the field of cancer research, the issue of cancer treatment remains framed as one of tragic choices. This paradox is arguably explained in part by a stubborn adherence to the four abovementioned premises – an adherence that monopolises the discourse on priority-setting and expensive cancerdrugs to the extent that it inhibits any other understandings of the issue beyond that of tragic choices. After identifying these premises, apparently so deeply ingrained in the discourse, the question therefore soon arose: why have they not been challenged?

One explanation for this unwillingness to challenge the four premises, and to us the most salient, stems from the standpoint of what is, or appears to be, morally acceptable. It seems, from our study of the material, that these premises claim a moral and ethical superiority. They speak to the rights of the suffering cancer patient to be both heard and saved, as well as to the insistent hope that the field of cancer research will indeed provide that salvation, through curative drugs. Because the premises thus appear to stand on moral high ground, the prospect of challenging them in contrast becomes unethical and cold-hearted. The sociological perspective offered by Norwegian sociologist Jill Loga helps us to understand the intricacies of such a mechanism, through her analysis of the interface between morality and politics in the Norwegian public sphere (Loga 2004). Loga proposes the idea of godhetsmakt, which we have translated into the term “power of goodness”. She considers how professing goodness affects discourse, and argues that by openly claiming to represent goodness, an argument gains a superior stance that makes it difficult for an alternate stance to claim legitimacy. She states that:

[...] open goodness has the ability to define its opponent. This creates a great discursive power. It becomes impossible to oppose against the open goodness, because one would appear as evil, cynical or egotistical. If one can administer and preach from the position of goodness, one becomes unimpeachable and immunized against criticism. Goodness needs only be expressed in order to become a conclusion (Loga 2004, p. 323).

This notion is well suited when considering the underlying mechanisms of the discourse on priority-setting and cancerdrugs, where each of the four premises arguably claim a power of goodness. We will demonstrate this with a brief consideration of each premise, understood through the power of goodness:

-

1.

Cancer drugs are expensive, but that is irrelevant because their administration saves lives.

-

2.

Cancer drugs work, and questioning this is indefensible because that amounts to questioning if cancer patients’ lives can be saved at all – which is painful to accept and cruel to consider.

-

3.

Any prolongment of life for a cancer patient is an absolute good, because it is evidence that we are trying to save them – and failing to try is wrong, no matter the pain or suffering our efforts might cause them.

-

4.

Patients, and their doctors, own the truth about cancer and cancer drugs – and questioning their ownership of this is disloyal to them, and both undermines the academic proficiency of medical professionals and enhances the suffering cancer patients are already subjected to.

These premises, by supposedly supporting the cause of cancer patients, claim moral superiority, rendering all other arguments invalid as they in contrast represent an immoral stance. Indeed, by opposing the goodness of the four premises, counterarguments become unethical. Thus, these premises gain discursive control, and through their incontestability maintain a monopoly of the discourse. Loga further suggests that through lack of opposition, the goodness discourse becomes self-reinforcing as ‘discursive power forces one down a goodness spiral’ (Loga 2004, p. 324). The discourse thus loses its nuance and stifles the many and varied opinions one intuitively would have expected these issues to give rise to. The four premises become four truths, as the public for lack of opposing arguments accepts them as foregone conclusions. This demonstrates, as Loga argues, ‘the power of definition in the incontestable’ (Loga 2004, p. 323).

The notion of the “power of goodness” becomes prominent also in the seemingly insufficient ability of the newsmedia to challenge the current future imaginaries of cancer treatment – exemplified by the inherent optimism surrounding immunotherapy. The actors in the field of cancer, and their normative visions, are rarely (if ever) challenged by journalists, and one could argue that this reflects the idea of one party claiming the position of goodness, and the other thus rendered unethical. By challenging experts who are trying to do something indisputably good – treating, or at times curing, cancer – one is portrayed as the party opposing the inherent goodness of helping these patients. Journalists seemingly accept the optimistic narrative surrounding precision medicine without hesitation, and indeed present it as the solution we have all been waiting for. The discourse thus becomes oversimplified and unilateral – an injustice to a field as complex as that of cancer research.

Cancer and Cancer Research: An Issue of More Than Tragic Choices?

It remains surprising to us that the issue of priority-setting and cancerdrugs is so stifled in the public discourse, particularly because our experience from both private conversations and public debates suggests that it is an issue that ignites impassioned opinions – arguably for several reasons. First, the story of a suffering cancer patient is relatable; as populations age and incidence rates of cancers increase, most of us have either had cancer or know someone who has. The issue is relatable because it is personal. This also means that the issue is important to us because we know that the decisions made top-level today have a direct impact on our own future health and treatment options, or on that of our loved ones. Thus, we are deeply invested in the decisions made by authorities, and the public debate surrounding these decisions – although it is not our health that is threatened today, or our story that is portrayed in the newspaper right now, we know it could be us tomorrow.

Secondly, this issue arguably stirs us deeply precisely because of its tragic nature. Our study of the material suggests that the general public – unsurprisingly – holds the view that there is something inherently wrong and unjust in denying a suffering patient the right to treatment, if we believe that treatment might help them. It seems to go against our nature to accept death – particularly deaths we believe might have been prevented, or at least delayed. However, we would argue that these views are partly based on understandings of the issue that are misinformed, largely due to the discourse’s adherence to the abovementioned four underlying principles. In order to achieve a meaningful debate on the issue of cancer and cancerdrugs, it is essential that arguments within this debate are based on accurate understandings of the issues it concerns itself with. This seems particularly important in relation to the second and third premise. Without a genuine and critical consideration of the actual efficacy of these drugs, it seems impossible to have any meaningful debate on the decisions made in relation to these drugs’ implementation – and only serves to further polarize the debate. Further, without a genuine understanding of what the life and time gained through treatment with these expensive drugs indeed looks like, we are doing cancer patients a disservice. If we ignore the possible negative outcomes of failed treatment and harmful side-effects, we are uncritically arguing for costly treatments that potentially rob patients of whatever quality of life they might have had in their final months or years. Herein lies real injustice.

Because adherence to these premises undermines the discourse, as well as any meaningful progression in the debate, the issue of cancer and cancer treatment remains one of tragic choices. Further, even in the world’s richest countries, as highlighted by the covid-19pandemic and the very real and tough choices that have had to be made in emergency rooms and intensive care units all over the world, our health care expenditure has a limit, and healthcare resources are exhaustible. One could argue that the persistent tragic choices framing of the issue of cancer and cancerdrugs further enhances the imbalance between financial constraints and public expectations, and blocks our path not only to a more constructive public discourse, but also to attaining an overall better outcome and improved care for cancer patients.

Alternative Imaginaries

Having stressed the importance of challenging the current discourse on cancer and cancer research in Norway, a natural next step is to consider what the discourse could look like when the premises that underlie it are questioned – and if this might alter the current framing of the issue as one solely of tragic choices. We have done this by considering alternative future imaginaries. Whilst frames say something about the past and the present and how we understand reality today, imaginaries are a particular way of “futuring”, or imagining what could be. Interestingly, one could argue that at least one of the premises that underlie the discourse, and thus one of the framings that are prominent in it, is in fact more resemblant of an imaginary than of a framing. This pertains to premise number one, namely that new and expensive cancerdrugs work and that their efficacy need not be questioned. In studying the discourse more closely, it becomes apparent that this framing often points not to the current status of cancer treatment and cancer research, but more towards the hope of what they might become. There are countless articles pointing to the idea that the drugs currently being developed will work, that they will have less side effects, and that they will be cheaper – and that this justifies both their use today and the investments we place in pharmaceuticals in order to allow for their enhancement. This is a sidenote to our following exploration of imaginaries, but nonetheless worth noting.

The imaginaries we now present are intended to complete each other in terms of providing an interplay between various political and philosophical levels of the issue at hand. Some are concerned with institutional change and political reform. Others suggest the need for a cultural shift in perceptions of how we as a society view illness and health. We have also considered philosophical aspects of society’s views on life and death, and how future imaginaries on this level could challenge current perceptions. Though we will not provide comprehensive analyses of these imaginaries, we propose them in order to challenge the current framings of the issues relating to cancer and cancer research, and the premises that underlie the discourse on these issues (Stenmarck et al. 2021).

A cornerstone to the issue of priority-setting and cancer care is the immense costs of new cancerdrugs, and the price tags they are often associated with. Within a market economy and with fiscal policies that necessarily put constraints on health care budgets, this makes healthcare a commodity that can be bought – at a price. One alternative imaginary is institutional change, whereby one, through major changes to social policies and financial models, changes the system through which we provide healthcare. This would entail a comprehensive analysis and a considerable review of the current healthcare model, which allows Big Pharma to set the prices they want rather than the payment they need (WHO Technical report 2018).

A second imaginary relates to current public perceptions of illness and health. It would seem that current cultural perceptions of health deem it the opposite of any discomfort – indeed, the WHO defines health as ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being’ (WHO FAQ 2020). This suggests that any deviation from a perfect state of health equals disease, and arguably enhances the perception we hold that any deviation from this state must therefore be treated. This coincides poorly with healthcare budget limitations, as well as with ageing populations, and we therefore wish to propose an alternate imaginary where perceptions of disease and health are challenged: where we accept health as a continuum, and where absence of disease is not the only element that defines it. Doing so would also challenge the premises that underlie the current discourse, particularly the premise that any prolongment of life for a cancer patient is an unequivocal good. If that prolonged period involves a level of suffering, we are arguably not providing the patient with an overall improved health outcome.

A third imaginary which we wish to briefly explore is perhaps controversial, but nonetheless interesting as it highlights how pervasive the notion that diseasemust be treated has become. In this imaginary we consider a scenario where society as a whole comes to the conclusion that certain cancers have become so prevalent, their treatments so costly, and the treatment results often so marginal that we decide to abandon the notion that these cancers can and should be cured, and rather take the approach that the healthcare system aims to provide care. That we choose to no longer provide treatment as such, but rather to help the affected individual by alleviating their pain, and to cope with the suffering associated with a terminal illness. In doing so, we accept disease as a necessary evil of life – rather than denying death as a basic condition of it. This imaginary may seem both radical and crude – which arguably highlights how deeply entrenched healthism has become in modern society (Stenmarck et al. 2021).

A fourth and final imaginary is related to the power given to single future visions by the media. The prominent vision of precision oncology is a vision that extends beyond just the medical, and should, in our opinion, be considered as such. As this vision is founded on normative concepts and has the potential to form and alter fundamental societal structures, it should be critically examined in line with other political issues. Thus, understanding that cancer research and the alleged promise of precision medicine is more complex than what is being portrayed in and communicated through the media, is an understanding that should be taken seriously. To achieve a responsiblemedia discourse on cancer and cancer research requires both that journalists and editors are more critical of established truths in the field of the research they cover, and that researchers themselves dare to communicate potential challenges and weaknesses in their own visions of the future.

Lack of Nuance in the Field of Cancer and Cancer Research: Why?

Thus far, we have attempted to illustrate the stagnation of the discourses on cancerdrugs and cancer research. We have explored why the four identified premises of the discourse remain unchallenged, particularly in light of the notion of the power of goodness. We have questioned if perhaps the issues of priority-setting and cancer could be framed through other lenses than solely that of tragic choices, and attempted to highlight the disservice one does both to cancer patients and to the discourse itself by employing this lone view. Finally, we suggested some future imaginaries, as a way of exploring other potential futures of cancer treatment and cancer research. Throughout, we have attempted to highlight the obvious and common finding of our research: the complete lack of nuance on the discourses of both priority-setting and cancer, and cancer as a research field. As this chapter draws to a close, we wish to pose the obvious question: why? Why is a field such as cancer and cancer research, so obviously complex, reduced to a presentation in the newsmedia that so poorly represents the realities of its complexities?

In the material we have studied, all of which was sourced from the newsmedia, we made the interesting observation that while studying the over 500 articles we had collected, it was surprisingly difficult to distinguish between them in terms of style of writing, type of article and newspaper outlet. Not only was there a very stereotypical presentation of cancer as a scientific field, with a clear focus on the black and white “facts” of its scientific findings and a lack of appreciation of the ambiguities inherent to it. But more surprisingly, whether the article was a news report, an opinion piece, an editorial, a column or a feature article, the style was markedly similar and the angling – here too – un-nuanced. In other words, we could not from the style of writing or layout clearly distinguish which pieces were written by professional journalists, and which were commentaries or opinion pieces from the general public. We will not delve deeply into what the causes of this may be, but simply question if this is suggestive of failings in the state of journalism generally. It seems one might deduce that the newsmedia holds itself to sub-par standards in its presentation and framing of cancer and cancer research – which is startling, considering the vast interest it has shown on these issues.

That being said, it would be an over-simplification to point only to faults of the newsmedia as an explanation for the lack of nuance in the public discourse on cancerdrugs and cancer research. We would argue that the lack of appreciation for these nuances is evident not only in the media, but in broader understandings and a wider context pertaining to the field of cancer more generally. Considering the scope both of the disease that is cancer, and of the research field that seeks to obliterate it, it is indeed peculiar that there is not a greater acknowledgment or appreciation for the complexities within it. A central purpose of this book is to attempt to reduce some of the ambiguity in the field of cancer research – a first step must therefore be to acknowledge that there is, for whatever reason, considerable resistance to accepting this ambiguity. Perhaps this is in part due to a faulty public discourse, oversimplified and unappreciative of the complexities of the issues it concerns itself with. Perhaps it is caused in part by an unwillingness to accept these complexities, because it suggests that cancer researchers cannot easily eradicate this illness, and some of the deaths caused by it are thereby unavoidable. Perhaps it has to do with the imaginaries we have started to accept as realities – that the future of cancer treatment, precision oncology, will indeed provide us with a molecular precision that obliterates ambiguity. Perhaps researchers are doing too poor a job of communicating the enigmatic character of their research object, fuelling hopes that cancer is a fully understood, soon-to-be always-curable disease. Perhaps there are other forces, political or financial, that have something to gain from oversimplifying our understanding of the field of cancer research, feeding our hopes that it can cure the diseases it researches, and thus also fuelling our willingness to pay for it. These are questions we will not attempt to answer – but our analyses and findings suggest they are worth contemplating.

Conclusion

The issues of cancer, cancer treatment and cancer research are complex, and will unfortunately continue to involve a certain degree of tragedy: they concern the loss of health, or ultimately life, for millions of people. Whatever progress precision medicine and cancer care makes in the coming years, there is no cure to all cancer disease – and we remain mortally vulnerable to its advance. We face a reality where patients will continue to be denied access to drugs they want, whether for lack of any expected positive outcome or due to financial restraints.

Having performed studies that considered the public discourse on these issues from 2013 to 2017, it therefore alarms us to see that the discourse fails to accurately depict the realities of priority-setting and cancer, as well as the promise of cancer research. Further, it is regrettable that the discourse continues to so heavily rely on premises that lack vigilant questioning and consideration. We believe the adherence to these premises enhances the perception that cancer and cancer treatment is an issue solely of tragic choices – and thus inhibits alternative perspectives that would better do justice to the complexity of these issues. We argue that a wholesome and sober approach, through a more responsiblemedia discourse, might reveal that these issues need not solely be framed as issues of tragic choices. Cancer disease, cancer care and cancer research are more than that, and undermining their complexity does neither patients, doctors, researchers or society as a whole any favours.

Notes

- 1.

This is part of the ethical guidelines of the Norwegian news press named Vær varsom-plakaten (Pressens faglige utvalg 2021).

- 2.

Some examples of headlines from the opinion pieces: “Future cancer treatment – bring your own data” Aftenposten, 21.12.17”, “Open the Nordic boarders for research and treatment” Aftenposten, 18.05.17”, “Machines must learn to detect how dangerous the cancer is” Aftenposten, 17.08.17” [our translations].

References

Bennett, W.L., R.G. Lawrence, and S. Livingston. 2006. None dare call it torture: Indexing and the limits of press independence in the Abu Ghraib Scandal. Journal of Communication 56: 467–485.

Blanchard, A., and R. Strand. 2017. Cancer Biomarkers: Ethics, Economics and Society. Kokstad: Megaloceros Press.

Blasimme, A. 2017. Health research meets big data: The science and politics of precision medicine. In Cancer Biomarkers: Ethics, Economics and Society, ed. A. Blanchard and R. Strand, 95–110. Kokstad: Megaloceros Press.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, CMS. 2018. National Health Expenditure Data. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html. Accessed 20 May 2019.

Eide, M. 2011. Hva er journalistikk. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Entman, R. 1993. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58.

Fleck, L.M. 2013. “Just Caring”: Can we afford the ethical and economic costs of circumventing cancer drug resistance. Journal of Personalized Medicine 3: 124–143.

Galtung, J., and M.H. Ruge. 1965. The Structure of Foreign News. The Presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus Crises in Four Norwegian Newspapers. Oslo: Peace Research Institute.

Gamson, W.A., and A. Modigliani. 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: A constructionist approach. American Journal of Sociology 95: 1–37.

Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organisation of Experience. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Jasanoff, S., and S. Kim. 2009. Containing the atom: Sociotechnical imaginaries and nuclear power in the United States and South Korea. Minerva 47: 119–146.

———. 2015. Dreamscapes of Modernity. Sociotechnical Imaginaries and the Fabrication of Power. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press.

IMS Institute for Health Informatics. 2016. Global oncology trend report. https://morningconsult.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/IMS-Institute-Global-Oncology-Report-05.31.16.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2020.

Loga, J.M. 2004. Godhetsmakt. Verdikommisjonen – mellom politikk og moral [The power of goodness. The value commission – Between politics and morality]. PhD thesis for the University of Bergen, Norway.

Medienorge. 2019. Lesertall for norske papiraviser – resultat. http://medienorge.uib.no/statistikk/medium/avis/273. Accessed 1 Feb 2021.

National Cancer Institute. National Cancer Act of 1971. https://dtp.cancer.gov/timeline/flash/milestones/M4_Nixon.htm. Accessed 22 Mar 2021.

Schudson, M. 2003. The Sociology of News. New York/London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Stenmarck, M.S., C. Engen, and R. Strand. 2021. Reframing cancer: challenging the discourse on cancer and cancer drugs—a Norwegian perspective. BMC Med Ethics22, 126 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-021-00693-5

Pressens faglige utvalg. 2021. Vær Varsom-plakaten. https://presse.no/pfu/etiske-regler/vaer-varsom-plakaten/. Accessed 25 Feb 2021.

WHO. 2018. Technical report: Pricing of cancer medicines and its impact. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/277190/9789241515115-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 1 Sept 2020.

———. 2020. Frequently asked questions. https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions. Accessed 26 Sept 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stenmarck, M.S., Nilsen, I.W. (2022). Precision Oncology in the News. In: Bremer, A., Strand, R. (eds) Precision Oncology and Cancer Biomarkers. Human Perspectives in Health Sciences and Technology, vol 5. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92612-0_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92612-0_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-92611-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-92612-0

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)