Abstract

The narrative is framed within the context of ways that public health interventions balance the rights of individuals and community when related to infectious diseases. This central example is from a community-based HIV testing program in an area with high HIV prevalence. We describe a breach of confidentiality resulting from an involuntary disclosure of a participant’s HIV status. This breach of confidentiality occurs within a family. The narrative considers the respective rights of individuals and community members related to disclosure of HIV status and pays attention to how roles (e.g., health care worker, sexual partner) influence decisions regarding disclosure of someone’s HIV status. There were clear testing program guidelines for how, when, and where to disclose HIV status of household members. Standard operating procedures and careful training were meant to protect data confidentiality and privacy of patients. In practice, things were messier and less clear. The narrative describes how this confidentiality breach occurred, what was done to ensure the participant was safe after the fact and ways to amend the breach on a systems level.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Public Health Ethics Issue

The ethical issues underlying our narrative relate to disclosure of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status and protection of privacy and confidentiality in public health programs. Public health officials have duties both to protect privacy and confidentiality and to safeguard the public’s health by making efforts to prevent diseases. Our narrative portrays the challenge of these ethical issues in the context of a community household HIV testing project that employed a variety of staff members. One of the lessons learned from this narrative involves appropriate training for staff to ensure they understand their duties and responsibilities.

Background Information

HIV disclosure refers to the process of revealing a person’s HIV status, either positive or negative. Persons are free to disclose their HIV status voluntarily, but involuntary disclosure occurs when a person discloses another person’s HIV status without that person’s permission. HIV disclosure involves peoples’ attitudes, emotions and behaviors, which can impact disease spread. It plays a presumed role in preventing transmission on the assumption that people aware of their HIV-positive status will not intentionally infect others. At the same time, disclosure of their status puts individuals at potential risk for stigma and discrimination (Obermeyer et al. 2011, 1011; Bott and Obermeyer 2013, S11). This risk may discourage individuals from voluntarily disclosing their status, while the fear of involuntary disclosure may discourage them from seeking testing or treatment.

In a 2011 review from 231 sources globally, Obermeyer, et al. found most persons living with HIV disclose their HIV positive status (Obermeyer et al. 2011, 1011). Women more likely will share their HIV status than men. Both men and women are more likely to disclose their HIV status to a woman than to a man. In sub-Saharan Africa, 26 studies show 65% of men and 73% of women disclosed their status. Disclosure closely correlates with expectations of emotional, social or financial support. It occurs more commonly with relatives than with friends, and partner disclosure is higher with steady partners than with casual partners (Obermeyer et al. 2011, 1014). Involuntary disclosure can take many forms. Health care workers may disclose a patient’s status inadvertently due to circumstances (e.g. lack of private spaces). Conversely, it may be intentional when related to a desire to protect another person (e.g. sexual partner) from becoming infected. Involuntary disclosure may also be malicious, when someone has access to HIV test results and uses this information to hurt, threaten or punish a person.

Gender differences matter in HIV disclosure, notably in the sub-Saharan Africa setting for our narrative. Women there more often undergo testing for HIV than men, largely because routine testing for HIV occurs during antenatal care. They also suffer more negative consequences after testing HIV-positive due to their vulnerable status (Bott and Obermeyer 2013, S10). In much of sub-Saharan Africa, “women’s economic and social vulnerability relative to men, fear of rejection, abandonment or violence by partners remain a major barrier to both testing and disclosure” (Bott and Obermeyer 2013, S10). Further findings in the United States show that rural women especially dread having their community learn of their HIV status (Sowell et al. 2003, 32). The triple burden of being female, living in a rural area, and having low socio-economic status create impediments to HIV disclosure. Despite this, women still more often disclose their HIV status than men (Obermeyer et al. 2011, 1012).

The complex and fraught issues surrounding disclosure raise many potential conflicts between competing values such as individual and community values (Obermeyer et al. 2011, 1014–1015; Bott and Obermeyer 2013, S11–S13). For example, persons who use drugs and share injecting equipment arguably have as much right to be informed and protected from contracting HIV as people living with HIV have a right to privacy protection (UNAIDS 2013, 23). Both the right to be informed and the right to privacy derive from the principles of autonomy and respect for persons, which both apply equally to individuals. Public health practitioners often must confront tensions between their duty to protect the community, including sexual partners and others, and the claims of individuals to privacy. These tensions can come to a head in situations where non-disclosure of an individual’s HIV status could contribute to disease spread. Laws have been enacted that criminalize non-disclosure of HIV status due to its potential to seriously harm others. As of 2018, 26 U.S. states had laws that criminalize HIV exposure, 19 that require persons aware of their HIV status to disclose it to sexual partners, and 12 that require disclosure to needle-sharing partners (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2019). UNAIDS (2013) has expressed “serious concerns about the nature and impact of criminalization of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.” They point to three main concerns: (1) science and medical knowledge do not support them, (2) they disregard standard criminal law principles and (3) their resultant disproportionately harsh sentences are counterproductive (UNAIDS 2013, 7).

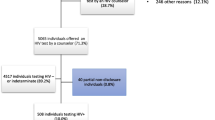

In countries with high HIV prevalence where control of the epidemic has almost been attained, multiple public health efforts are often underway to identify new positive cases of HIV infection (Kim et al. 2019, 2–3; UNAIDS 2020). These include case-based surveillance, HIV recency testing, and index partner testing. HIV recency testing uses a lab algorithm to detect if the infection is new (acquired within past 6 months). These strategies use of a series of detailed questions or lab tests to learn more about how people newly diagnosed with HIV became infected. In implementing these strategies, public health officials must balance privacy protections for individuals with a larger goal of community health. For instance, with index partner testing, people living with HIV disclose names of their sexual partner(s) to healthcare workers. Those workers then attempt to contact the partner(s) and offer an HIV test. Collecting such personally identifying information serves dual purposes: preventing HIV spread among sexual partners and ending HIV transmission in the larger community. These dual purposes, however, generate some level of conflict between an individual’s right to privacy and the greater goal of stopping the spread of HIV (APHA2019, 8). That is because revealing HIV status contains some risk of inappropriate disclosure and stigmatization.

Several considerations for ethical analysis from the Public Health Code of Ethics are especially relevant to our narrative (APHA2019, 9). The first two considerations, accountability and transparency, are important preconditions for successful public health intervention. These create the support, cooperation and trust required from individuals and communities to implement public health interventions. That applies to the context of our narrative, a community household HIV testing project. Our narrative also indirectly suggests how ethical breaches left uncorrected could easily undermine trust and the ability of public health to conduct future projects collaboratively with communities.

The third consideration, permissibility, asks us to consider whether an action would be “ethically wrong, even if it were to have a good outcome” (APHA2019, 7). This consideration applies, for example, to index partner testing, which aims at the desirable outcome of reducing HIV transmission. The question is whether doing such testing would violate some other value, right, or rule that would make it impermissible. Disclosing the names of sexual partners intrudes on these partners’ privacy, something people generally value and try to protect. Strict protocols, however, limit how practitioners can use this information, so that it remains confidential. Ethical analysis suggests that under these protocols, index partner testing results in a permissible trade off. In this case, the benefits both to the sexual partners and society at large presumably outweigh the potential harm to these partners. However, our narrative raises the more ethically fraught issue of permissibility via an event that occurs in the context of a public health program. The event occurred despite protocol and program guidance intended to protect participants.

That same event, which involves a project staff member’s involuntary disclosure of a woman’s HIV status, also implicates a fourth consideration, respect. This demands that we consider whether a proposed action would be “demeaning or disrespectful to individuals and communities even if it benefited their health” (APHA2019, 8). In an ethical sense, respect should apply equally to everyone regardless of status, though respecting everyone’s rights equally can prove challenging. This holds true especially where privilege, power, or patriarchy override respect for the rights of women, the underprivileged, or community members who are subject to stigma. As with permissibility, ethical assessment becomes more difficult when an ethically suspect action benefits others, especially a person who is disrespected.

The Public Health Code of Ethics also gives guidance for specific functional domains of action in policy and practice, three of which are especially relevant to our narrative (APHA2019, 11). Domain 1 refers to conducting and disseminating assessments focused on population health status and public health issues facing the community (APHA2019, 11). A duty to protect community health and prevent the spread of disease where HIV is common entails conducting community assessments of the prevalence of disease. The guidance recommends that safeguards be in place so that information gathered does not harm individuals or communities. In the small, rural community setting of our narrative, protecting the privacy and confidentiality of individuals when gathering data is especially important.

Domain 8 calls for maintaining a competent public health workforce, which entails providing ongoing training in all relevant areas (APHA2019, 24). The main event of our narrative involves a staff member of the logistics team whose lack of training results in a breach of protocol. Finally, domain 9 calls for evaluation and continuous improvement of processes, programs, and interventions (APHA2019, 25). Especially when breaches occur, it is crucial to engage a wide variety of stakeholders in the improvement process. It is helpful to develop a strategy involving measurable goals for improvement and regular reviews of processes to ensure continuous improvement and minimize lapses. Such breaches and the response to them also raise issues of responsibility and accountability.

Approach to the Narrative

In this narrative we describe a breach of confidentiality resulting from an involuntary disclosure of HIV status. The breach loosely follows similar events that have occurred during implementation of household HIV testing and counseling efforts by field teams who received cadre-specific training. Countries where community-based household HIV testing has been performed usually have generalized HIV epidemics where up to one out of every four people live with HIV (WHO2016). Staff training generally includes clear guidelines regarding disclosing HIV status and information on how to protect data confidentiality and client privacy. In some instances, not all team members receive this training, notably non-technical staff (e.g., drivers, logistics managers). As this story is a composite informed by the types of challenges occurring in various situations and settings, the details are fictional, including names. As you read this narrative, we suggest that you consider the respective rights of individuals and community members as they relate to disclosure of HIV status and pay attention to how roles (e.g. health care worker, sexual partner) influence decisions regarding disclosure of someone’s HIV status.

Narrative

What Maria enjoyed most while driving was the hospitality of people in an otherwise inhospitable land. As she drove the long, empty stretches separating towns, she felt strongly connected to the people of her country and deeply satisfied with this position. Maria drove a large van for HIV testing and counseling team members that promised to reach many households with HIV testing and referrals to medical or other services for those who needed them. She took her responsibilities seriously to convey the team (counselors, nurses, etc.) and to unload carefully the equipment needed for each household. The job also gave the naturally social Maria an excuse to travel, something she liked nearly as much as she enjoyed chatting with colleagues, local shopkeepers, and even the household members. Within weeks of joining the team, Maria started to become an expert on the local weather’s effect on crops, restaurants with the tastiest food, and shops with the most reasonably priced yet exotic items. Her ability to blend in like a local, no matter the town, filled her with pride.

On this day, on the second stop of the afternoon, Maria was just shy of dozing off in the van. A household member who had completed testing wandered out for some fresh air, while the remainder of the team stayed inside. She stretched out her hand and greeted “I’m Aunt Pauline.” Maria didn’t say anything but wondered why the woman referred to herself as Aunt Pauline. She soon learned, the household members were Uncle Elijah, his wife Aunt Pauline, their 23-year-old niece, Kandy, and her infant. Everyone now referred to her as Aunt Pauline because family life revolved around Kandy and her baby. Aunt Pauline, tall and welcoming with an engaging disposition had firmly shaken Maria’s hand. Maria, welcoming the distraction, stepped out of the van and said, “Pleased to meet you, I’m Maria, the team’s driver.”

“Say Maria, those are some shoes you’ve got on,” remarked Aunt Pauline. “Yes, they are. They’re custom-made leather shoes I just picked up last week, not far from here.” Her shoes were becoming a great source of pride as they drew attention from everyone. “Well, I expect you won’t be holding out on me. Was the shop expensive?” “Truth be told, it’s a real find. Every pair is hand-made, and the man who runs the place has been in business nearly 8 years. Pays real attention to detail, but he struggles to compete with retail prices. I actually wondered if he was selling these at a loss.” Aunt Pauline insisted Maria give her details about the shoemaker. Honestly, Maria could not remember so they exchanged phone numbers so she could relay the shoemaker’s contact information once she returned home.

Meanwhile, Werner, a counselor with the team, was talking with Uncle Elijah and his niece. Werner first sat Uncle Elijah and later Kandy down on a chair in the most private corner of the kitchen, opposite the open doorway that led from that room into the next. After being counseled, Uncle Elijah and then Kandy placed her copy of the informed consent form on the counter within easy reach. The two alternated being interviewed by Werner and caring for the baby in the other room. It was long, yet the counseling process didn’t seem to bother the family. There was a nice rhythm to the whole affair.

After the counseling was complete, Werner mentioned it was time for the HIV testing portion of the visit. He introduced Festus, the nurse. Festus indicated that if Kandy were interested and willing, the baby could also receive an HIV test. Kandy eagerly agreed. It meant she could avoid the inconvenience of getting to the noisy, crowded and somewhat remote health clinic. Next, Festus returned with Aunt Pauline to the kitchen corner to review the consent process, provide pre-test counseling, and explain how a HIV rapid test is conducted. He then described what the results would mean, clarifying how a positive test result for HIV would lead to a referral for treatment at a nearby health clinic.

By the time Kandy’s turn came to be tested, her confidence had drained. She peppered the nurse Festus with questions. “Will Aunt Pauline and Uncle Elijah know our results? Is there any chance the test is wrong? Are you going to use a needle on the baby?” Festus, used to such questions, reassuringly answered, “Your results, and your baby’s results, will not be shared with anyone else in the household. The test is very accurate, but there is a small chance that it could be wrong, or inconclusive. The laboratory performs quality control on its specimens, and we will ensure that you are notified of your result, if it is different from what you are told today.” Lastly, Festus pulled out a small lancet and assured Kandy that the collection procedure was quick, and although her daughter would feel a prick in her foot, it was hardly anything she’d remember.

Festus, carefully followed the standard procedures and handed each household member their individual result. Uncle Elijah, Aunt Pauline, and the baby all tested HIV-negative, but Kandy tested HIV-positive. Festus privately shared with Kandy information about her diagnosis, where treatment was available, and how to prevent transmission of HIV to her baby.

Since it was time to go, the team piled into the van after saying good-bye to the family. Werner and Festus had to be dropped off at another household where their work conducting counseling and testing would continue, but Maria went for a meal. She had asked where to get good food at a reasonable price. The food was just arriving when Maria’s phone rang so she stepped away from the table and answered “Hello, this is Maria.”

“Maria! This is Aunt Pauline, how’s it going?” she asked rhetorically. “Good, good,” Maria replied, “but I haven’t returned home yet. I can’t get the shoe shop details until then. I’ll be at least another five days on the road doing testing.” “I’m not calling about that, actually. I’m calling to let you know that your team didn’t provide my niece a copy of her result. When I went through her papers, she’s only got a copy of her consent form. She insists that it’s not a big deal, but I feel otherwise. I don’t want her test results floating around in your van. That wouldn’t be professional.” This seemed an understandable concern to Maria, who wanted to support the team. “Listen, Pauline, I’m sorry to hear that. I’m sure it’s just a misunderstanding. Why don’t you give me a chance to chat with the team?”

Maria dialed Werner but got no answer. Likely, he was conducting another counseling session. Her next move was to contact Festus. It was he, after all, who had conducted the tests. “I did the consent and the counseling appropriately,” Festus retorted defensively, “and I definitely gave Kandy her results. I surely remember that because she was the only one in the household that tested HIV positive. That’s probably why she’s not sharing them with her Aunt,” she speculated. “Yeah,” agreed Maria with some sympathy, “that’s tough news to take.” Maria generally didn’t imagine what it’s like to learn that kind of news. “Devastating,” he said. Festus added “I just felt happy that the baby is OK. I worry for the baby whenever the mother tests positive. It’s a good thing this project includes HIV testing for all family members. We can prevent the spread when more people know their status and get onto treatment.”

Later, Aunt Pauline called again. “Pauline, how’s your evening finding you?” Maria began. “It’s good, but I’m still feeling quite uneasy. I was hoping you could tell me if you found out any information? I’m wondering if the team can provide my niece with her result. It seems that we should have that in-hand before you move on to your next place. I don’t want you leaving and forgetting to come back with it.”

“Yeah, so about that. I called the nurse to find out what had gone on. He told me that Kandy should have the paper in hand. It’s some tough news, Aunty. The baby is good, but Kandy is not OK. That might be why she doesn’t want to share the news. She needs to go to the clinic and start taking treatment for HIV.” “I cannot believe this!” interrupted Kandy, sputtering through closed teeth and a clenched jaw. Only then did it become apparent to Maria that the phone had been on speaker. “Festus promised to keep my status a secret! He told me that no one else would know, but you betrayed my privacy.” Maria could hear Kandy’s voice soften, then break into tears. At that moment, Maria wasn’t sure what to say. Her apology fell short, even as it was leaving her mouth. She hung up the phone and dialed Werner to let him know what had happened.

Soon after, Festus returned to the household to apologize to Kandy. Festus asked whether Kandy felt safe staying in the home and whether there was anything the team could do at this time. “I feel safe enough to stay here. It’s my home. I just wish I could have had a chance to break the news in my own time” is all Kandy said.

Festus, Werner and Maria notified their supervisor about what happened and how Kandy responded. The supervisor suspended Maria and Festus from further work and alerted the project leads about the breach of confidentiality. Festus subsequently resigned from the project because he had violated the country’s nursing code by disclosing a client’s HIV status. Maria requested an official hearing on the matter, as allowed under the policies of her organization.

In response to this incident, the project management sent a memo to all teams to remind them of the importance of adhering to confidentiality and privacy guidelines and not to discuss clients’ HIV status or test results with anyone outside the relevant counseling and testing staff. Additionally, they reminded drivers that directly engaging with clients was outside the scope of their work. This restriction included the exchanging of personal information, such as phone numbers, with household members. Project management also distributed a data confidentiality agreement that each driver was asked to review. The agreement stipulated that drivers were not to access or share any private information about clients while performing their jobs. All drivers were required to sign the data confidentiality agreement as a condition of continued employment. Other professional staff already had signed such agreements previously during their initial training for the project.

A week after the disclosure of Kandy’s HIV status, the project leadership arranged a meeting with heads of their organization. They discussed the incident and the need to communicate it to the project oversight committee. They also planned a joint visit to offer support to Kandy.

On the day planned, they drove together to Kandy’s home and apologized to her again. They provided her with an update on the disciplinary measures applied, including Maria’s suspension and the resignation of the nurse, Festus. Kandy let the team know that her relationships with Uncle Elijah and Aunt Pauline were unaffected, and that she had sought HIV treatment the day after the incident using the referral form that project staff provided. It seemed unlikely that Kandy would forgive the project team’s actions anytime soon. The project staff resolved to learn from this mistake and to help educate others, hopefully preventing future incidents like this one.

The project oversight committee convened a hearing for Maria led by a neutral party and attended by representatives from partner organizations. During the hearing, the team supervisor described how the breach of confidentiality happened and how it negatively impacted a client. Maria described her actions and informed the committee how she had learned about a client’s HIV status from the nurse, Festus. Maria argued that she could not have shared the information with another family member if someone on the team had not told her the client’s HIV test result. Maria further testified how she had not been asked to sign a data confidentiality agreement until after the disclosure occurred. The outcome of the review was that Maria received an official warning. She was permitted to return to work with the clear understanding that she never exchanges personal information (e.g. phone numbers) with clients nor discloses confidential information about any clients. For the broader cohort of drivers, they received an additional training module on privacy, confidentiality and other ethics topics.

In summary, during such a household community project addressing a sensitive topic like HIV, ethical issues are bound to arise. This narrative portrays how a serious breach of confidentiality arose from a series of lapses and innocent actions that occurred during project implementation. The driver and a client struck up a friendship and exchanged personal phone numbers because of shared interest in a pair of shoes. This allowed the client to contact the driver, whereas ordinarily clients would only have contact details for staff listed on official materials (e.g. informed consent form). Because they all rode in the same vehicle and spent many hours together while implementing the project, they slipped into conversation about their shared experience. Festus did not weigh the consequences when he disclosed a clients’ HIV status to his teammate. Disclosing a clients’ HIV status seriously violated the country’s nursing code.

During the training period, drivers were considered non-technical staff and did not receive the same level of training in ethical protections as other staff, nor were they required to sign data confidentiality agreements. The supervisor might have anticipated that non-technical staff, such as drivers, can become deeply involved in these projects just by virtue of the time they spend with community members. Drivers may not hold the same status as skilled health workers yet during their work they may have similar access to personally identifiable information. More foresight on the part of the supervisor could have mitigated the risk with appropriate training and the signing of confidentiality agreements for all levels of technical and non-technical staff.

Discussion

There were clear project guidelines for how, when, and where to disclose HIV status of household members. Standard operating procedures and careful training were meant to protect data confidentiality and privacy of patients. In actual practice, things were messier and less clear. Project staff and participants shared spaces for multiple hours with household life going on around them. There was not always a private room with a closed door where project activities could occur. A community member, such as Kandy, with pained emotion or cries after learning her positive HIV result may have been seen or heard by family or other community members who then suspected or learned about the HIV positive status. Because of the project design, it was clear to household members that everyone was being tested for HIV if they gave informed consent. Even though results were only disclosed to the person tested (or in the case of children to the persons who consented on behalf of the child), household members commonly asked one another to share test results. In this way, the benefits of convenience in providing HIV testing services at the household are in tension with returning results privately due to a setting where family members are present.

Questions for Discussion

-

1.

Was the breach of confidentiality something that was likely to happen or easily foreseeable? Should the project supervisors have foreseen this breach could happen?

-

2.

How might the supervisors have prevented the breach, and were their efforts to correct the problem appropriate and sufficient?

-

3.

Why do you think Maria felt compelled to tell Aunt Pauline about her niece’s HIV status, along with that of her child?

-

4.

What motives may have led Kandy not to disclose her HIV status to Uncle Elijah and Aunt Pauline? How might her gender have influenced her decision to disclose her HIV status?

-

5.

How might each of the project staff have contributed to the breach in confidentiality and why?

-

6.

There is increased danger of breaches in confidentiality in small communities with high HIV prevalence because community members are more likely to know each other. In a small community setting, how should the dangers and advantages of testing be balanced?

-

7.

How could the project design be improved to provide additional privacy protections for community members?

-

8.

What principles, strategies, or values would you consider in weighing the benefits versus the costs of implementing such improvements?

References

American Public Health Association (APHA). 2019. Public Health Code of Ethics. https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/membergroups/ethics/code_of_ethics.ashx.

Bott, Sarah, and Carol M. Obermeyer. 2013. The Social and Gender Context of HIV Disclosure in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Policies and Practices. Journal of Social Aspect of HIV/AIDS 10 (S1): S5–S16.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. HIV and STD Criminal Laws. Last Updated July 1, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/policies/law/states/exposure.html.

Kim, Andrea A., Stephanie Behel, Sanny Northbrook, and Bharat S. Parekh. 2019. Tracking with Recency Assays to Control the Epidemic: Real-Time HIV Surveillance and Public Health Response. AIDS 33: 1527–1529.

Obermeyer, Carol M., Baijal Parijat, and Elisabetta Pegurri. 2011. Facilitating HIV Disclosure Across Diverse Settings: A Review. American Journal of Public Health 101 (6): 1011–1023.

Sowell, Richard L., Brenda F. Seals, Kenneth D. Phillips, and C.H. Julious. 2003. Disclosure of HIV Infection: How Do Women Decide to Tell? Health Education Research 18 (1): 32–44.

UNAIDS. 2013. Ending Overly Broad Criminalization of HIV Non-disclosure, Exposure and Transmission: Critical Scientific, Medical and Legal Considerations. Guidance Note. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20130530_Guidance_Ending_Criminalisation_0.pdf.

———. 2020. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics—2020 Fact Sheet. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2016. Estimated Number of People Living with HIV, 2016 by WHO Region. https://gamapserver.who.int/mapLibrary/Files/Maps/HIV_all_2016.png.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Additional information

Disclaimer: This paper is presented for instructional purposes only. The ideas and opinions expressed are the authors’ own. The paper is not meant to reflect the official position, views, or policies of the editors, the editors’ host institutions or the authors’ host institution.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Miller, L.A. et al. (2022). Disclosure of a Participant’s HIV Status During a Household Community HIV Testing Project. In: Barrett, D.H., Ortmann, L.W., Larson, S.A. (eds) Narrative Ethics in Public Health: The Value of Stories. Public Health Ethics Analysis, vol 7. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92080-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92080-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-91443-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-92080-7

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)