Abstract

Successful management of sociotechnical issues like those raised by the COVID-19 pandemic requires members of the public to use scientific research in their reasoning. In this study, we explore the nature and extent of the public’s abilities to assess research publications through analyzing a corpus of close to 5 K tweets from the early months of the pandemic which mentioned one of six key studies on the then-uncertain topic of the efficacy of face masks. We find that arguers relied on a variety of critical questions to test the adequacy of the research publications to serve as premises in reasoning, their relevance to the issues at hand, and their sufficiency in justifying conclusions. In particular, arguers showed more skill in assessing the authoritativeness of the sources of the publications than in assessing the epistemic qualities of the studies being reported. These results indicate specific areas for interventions to improve reasoning about research publications. Moreover, this study suggests the potential of studying argumentation at the system level in order to document collective preparedness to address sociotechnical issues, i.e., community science literacy.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Argumentation at the system level

- Community science literacy

- Appeal to expert opinion

- Argument mining

- Argument schemes

- Public use of research

- Science communication

- Public scientific argument

- Altmetrics

1 Introduction

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in the early months of 2020 forced all of us to form quick yet consequential views on complex sociotechnical issues. The maturity of open access publishing meant that in doing so we could freely draw on an increasing share of the world’s store of scientific knowledge (Piowar et al., 2018). And the ubiquity of social media gave us opportunities to press the science we discovered on each other (Colavizza et al., 2021; Fang & Costas, 2020). The pandemic, in short, provided an ideal growth medium for public arguments about scientific research publications.

Contemporary argumentation theory offers surprisingly few insights into such arguments. Adopting the familiar ARS framework (e.g., Blair, 2012), we know that arguers must be grappling with a series of basic questions: Is the research publication adequate to serve as grounds in reasoning? Is it relevant to the claim under examination? And does it, with other evidence, offer sufficient support for a conclusion? Beyond this widely applicable framework we have little understanding of the critical questions arguers use to assess the research publications they come across.Footnote 1 Mark Battersby’s excellent textbook, Is That A Fact? (2010) seems to be the only extended treatment of the topic. Intriguingly, at different points in the book he recommends distinct approaches.

Battersby’s first approach focuses on what we will call the epistemic quality of a research publication, that is, the quality of the scientific evidence it reports (Chap. 10 see also pp. 163–168). We can see this approach as an accommodation for general use of the sophisticated practices for systematic evidence reviews honed within the scientific community (e.g. Schünemann et al., 2013). Battersby wraps up his treatment of “evaluating scientific claims” with a set of heuristics urging attention to the design of the study reported and the strength of its results: “experiments are more credible than observational studies; prospective is more credible than retrospective; bigger is better; longer is better; more variety of studies is better; larger effects are more credible” and so on (pp. 149).

Battersby’s second approach shifts attention from the study reported in a research publication to the act of reporting itself. Here research publications are treated as one sort of material to be found online, and the focus is on “who is supplying the argument or information? Is the supplier a credible source? (Government organizations, academic institutions, reputable publications?) Is there bias (obvious or not so obvious) because of financial support, or political bias?” (pp. 174–5). This is the familiar terrain of the appeal to expert opinion (e.g. Walton et al., 2008): the assessment of what we will call the authoritative quality of a research publication.

This study aims to advance on these slender beginnings and deepen our understanding of the critical questions members of the public use to assess, and thus also to challenge and defend, the quality of scientific research publications. Presuming that skilled practitioners are already making good arguments, we adopt an empirical approach (Goodwin, 2020; Paglieri, 2021; Walton, 2005) to the investigation of arguments related to research publications. Are arguers focusing more on the epistemic or authoritative qualities of research publications? What specific standards, i.e., what critical questions, are they using to assess these qualities?

We take as a case study the early debate over the effectiveness of community use of cloth face covering (“masks”) in slowing the spread of the pandemic. As COVID emerged as a global threat, both WHO and the US CDC were recommending against widespread use of masks; the US Surgeon General even tweeted at the end of February, 2020:

Seriously people–STOP BUYING MASKS! They are NOT effective in preventing general public from catching #Coronavirus, but healthcare providers can’t get them to care for sick patients, it puts communities at risk!

But this official advice pushed up against the well-publicized and apparently successful practice of universal masking in East Asian nations, the increasing evidence of spread by non-symptomatic individuals, and the common sense appeal of creating a barrier between oneself and contamination. Throughout March an online movement quickly grew advocating for #Masks4All, together with a drive among makers undertaking a #MillionMaskChallenge (see Bogomoletc et al., 2021 for a more detailed history). Arguers in the emerging debate sought from scientific research answers to basic questions such as: Do masks work at all? If so, for what purposes and in what situations? What materials and designs are best? But they found few answers. There were only a handful of studies relevant to use of cloth face masks in community settings, and those provided only tentative and ambiguous answers.Footnote 2 While this was bad news for those trying to figure out what to do, it is good news for argumentation theorists: the deep uncertainties around the topic of masking can be presumed to drive increased care and effort by the arguers who were trying to draw what they could from the sparse scientific literature.

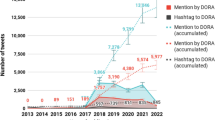

In order to explore the argumentative use of research publications (RPs) in the mask debate, we turned to a segment of a previously-collected corpus of RP-related discourse from early in the pandemic (Bogomoletc et al., 2021). In constructing that corpus, we began by identifying the research publications (RPs) related to cloth face-mask use which received the most public attention, relying on Altmetric, a service that provides information about the quantity of mentions of a scholarly article across multiple non-academic media. We identified six widely circulated articles with higher Altmetric scores as of May 2020; see Table 17.1 for details. We then used the Altmetric database to collect the English language, original posts on Twitter mentioning these RPs from January 1 to April 14, 2020, selecting the cut-off to be ten days after the CDC shifted its position to require masking, but before the intense tribalization of the mask issue in the US (Yeung et al., 2020). The resulting corpus consisted of 4775 tweets (including duplicates when a tweet linked to more than one of the target RPs).

One of us (Goodwin) then coded this data for features relevant to the argumentative use of RPs. Because we were familiar with the corpus from a previous analysis for other purposes (Bogomoletc et al., 2021), in the first round of coding we adopted a provisional coding strategy (Saldanha, 2016, p. 168) supplemented by in vivo coding (Saldanha, 2016, p. 105) of emergent features. We aimed to capture (a) the descriptors arguers used for the RPs, (b) the way arguers represented the content of the RP, (c) the way arguers assessed the quality of the RP, and (d) any additional features that might be relevant. For (a) we coded in vivo the noun(s) arguers used to refer to the study, the presence of date, journal or author information, the terms “scientific” (and variants), the term “peer reviewed,” and any other descriptors (in vivo). For (b) we coded whether arguers represented the content of the RP at all, and if so, what part of the RP they mentioned and how close was the representation to the RP itself; see Table 17.3 for the full list of codes. For (c) we coded in vivo both specific terms arguers used to express their assessment, and also marked any extended discussions of RP quality. For (d) we noted additional features that emerged during the coding as potentially relevant to arguers’ use of RPs, including the presence of a formal citation, mention of numbers from the articles, use of jargon, expressions of epistemic certainty or humility, and interpersonal put-downs. Finally, in a second pass we adopted pattern coding (Saldanha, 2016, p. 236) to review the initial coding, grouping the in vivo codes into larger categories and using the provisional codes to guide the development of themes.

In the following sections we lay out what the analysis tells us about the specific ways arguers assessed the adequacy,Footnote 3 the relevance, and the sufficiency of RPs for their decisions about masks. Our overall goal is to produce an improved account of critical questions related to RPs, both (descriptively) to deepen our understanding of sociotechnical argumentation and (prescriptively) to support improved pedagogy and practice. In addition, our examination of reasoning on social media contributes to the emerging theory of argumentation at the system level (Goodwin, 2020). Previous studies of the circulation of RPs on social media have focused on what the circulation means for science: on the effectiveness of social media for science outreach (Alperin et al., 2019) and what social media-based metrics of scientific impact actually measure (Woulters et al., 2019). But such a study can also be valuable for what it reveals about the public. Our success in managing situations like the pandemic (or climate change, or the impacts of new technologies) depends in part on our collective ability to bring scientific knowledge to bear through argumentative deliberations. The density and sophistication of social media arguments about RPs can serve as an indicator of how well or ill the public is accomplishing this task. Social media shows us the public mind at work; even as we can mine Twitter for sentiment to assess collective happiness (e.g., Hedonometer n.d.), we should be able to mine it for arguments to assess community science literacy (Roth & Barton, 2004; Snow & Dibner, 2016; Howell & Brossard, 2021), including the community’s capacity to identify, evaluate and deploy RPs. This study is an early step in developing the tools for such an assessment.

2 Adequacy

2.1 Assessment: Authoritative or Epistemic?

None of the six research publications (RPs) were recent, so we presume that those tweeting them were putting them forward as relevant to reasoning about the emergent situation of the pandemic–i.e., using them as adequate premises (Blair, 2012) within some larger structure of argument about masks. As discussed above, when arguers want to bolster or undermine the premise adequacy of a RP, they face a choice: they can reinforce/undermine its qualities as an authority that deserves to be followed, or they can reinforce/undermine its quality as epistemically sound results. Both of these approaches are legitimate–both authoritative and epistemically sound RPs can serve as adequate premises of arguments; however, each approach suggests a different set of assessment standards. Assessing RPs for their authoritative qualities frames them as utterances and focuses on who said what. Assessing RPs for their epistemic qualities frames them as studies and focuses on what evidence they offer in support of their findings. While arguers in this corpus deploy and critique research publications both as authorities and as studies, overall, authority dominated. In the following discussion, we document the emphasis on authoritativeness both in the terms arguers used to describe the RPs as well as the ways arguers deployed the RPs in their arguments.

Start with the terms. Extended, explicit discussions evaluating RPs are relatively rare in the corpus, perhaps due to the brevity required by the medium, Twitter. But arguers can provide implicit support for (or against) the adequacy of the RPs they tweet about in the choice of nouns they use to identify them and the adjectives or phrases they use to characterize them. As seen in Table 17.2, over a third of arguers provide this sort of information, and their choices tilt towards emphasizing assessment of authority. Source indicators are prominent in comparison to other information, suggesting that arguers view as important the authors, journals and institutions guaranteeing the soundness of the RP. Adjectives directly focusing on the credibility of the source or statement, such as “expert, not authoritative, peer reviewed, published,” are more common than epistemic adjectives focused on knowledge-producing activities, like “(not) evidence-based, anecdotal, empirical.” Very few tweets indicate what kind of study the RP reported–information key to any epistemic assessment of RP quality–and almost all of those refer to the MacIntyre RP, where the study type is named in the title. By contrast, the most common terms referring to RPs characterize them simply as “science, research” (terms also frequent as adjectives) or most frequently of all, as a “study.” For example:

They have zero actual disease blocking effect. Science.Footnote 4

Research!!

This is not a joke. Peer-reviewed science says even home made masks are effective.

That’s completely false, here’s a peer-reviewed study that says so:

Anyway, I’m done debating this. Real science says masks work.

Listen to the scientific studies.

Please remember, a #homemademask is not the same as a #medical mask! Follow the #Science !!!

Peer reviewed published research in a leading medical journal. But I’m sure your “belief” in cloth masks and trust in the non-scientist mayor is better to rely on. Lol. Just FYI:

Arguers are proceeding as if identifying a RP as “science”–sometimes intensified as “real” or “actual science”–is sufficient to establish its adequacy (cf. Thomm & Bromme, 2012). The last tweet in particular makes the contrast explicit: we can place our trust in authoritative science, or we can grant it to “non-scientists.” “Science” has spoken, and what it “says” must now be “listened to” and “followed.” Indeed, some arguers even position RPs as conclusive–as grounds to conclude that “debating” is “done.” Arguers are thus able to deploy RPs as interpersonal slap-downs, in which the opponents’ refusal to follow the science demonstrates their “stupidity”:

#COVIDIOT Read and learn.

Morons! “Penetration of cloth masks by particles was almost 97% “

bUt mAsKs DoN’t do aNyThing! Read this study, then get back to me

Authority is a relationship between persons; invocation of authority creates a situation where the opponent can appear to be a bad person if they fail to respond with appropriate respect (Goodwin, 1998).

The dominance of authoritative over epistemic assessment is evident not only in the terms in which the RPs are described, but also in the ways the RPs are used. Table 17.3 shows how arguers deploy the RPs in their arguments; the codes are listed in a plausible increasing order of sophistication, with tweets being assigned to the highest justifiable category. In this data, arguers’ interest in the RPs appears to be highly pragmatic. Nearly a quarter of tweets do not discuss the RP at all but proceed immediately to assert a conclusion that the arguer (apparently) draws from it (OPINION). Over a third provide only a general overview of the RP content (ABSTRACT, TOPIC, BRIEF SUMMARY). In these uses, the adequacy of the RP is simply presumed; the content at the other end of the provided link is manifestly “science,” and thus authoritative. By contrast, only about 10% of arguers demonstrate that they have read beyond the abstract, offering either a detailed summary (EXTENDED SUMMARY) or a reference to material in the body of the RP (QUOTATION, POINT). Many of these more sophisticated uses turn out to be stereotyped. For example, two thirds of the references to the Davies RP are to just one target: the table at the top of the second page of the article. This sort of convergence suggests that the arguers may be lifting passages from other arguers, not from the article itself. Thus overall, the uses of the RPs suggest that arguers are not undertaking epistemic assessment of the RPs. Indeed, some arguers even admit that they don’t have the capacity to do so:

I read this today. I’m not medically trained so may have missed the nuances.

@Atul_Gawande have you seen this? I think you tweeted recommending bandanas or cloth masks today. What do you think?

Would love to hear a comment from knowledgeable source regarding this study.

In the last two tweets, arguers are going on Twitter specifically to seek help from “knowledgeable” others in evaluating the study. Epistemic evaluation is best done by experts, and the experts’ judgment of RP epistemic quality is itself authoritative:

Don’t ask for a link to a scientific study if you think you’re smarter than the scientists who performed it, and every scientist who is saying we’ve read the study and it’s sound.:joy:

By contrast, there is only one tweet in the corpus seeking help with assessing the authoritativeness of a RP:

I sew and would love to help, but do cloth masks help? This study makes me wonder. But I’m also unfamiliar with these journals so I don’t know how trustworthy the study is.

Where arguers admit they are unable to assess the epistemic merits of RPs, in general they appear to feel confident of their ability to assess RP authoritativeness.

Arguers’ use of temporal indicators provides an interesting test case of the dominance of authoritative over epistemic evaluation of RP adequacy. In some cases, dates are mentioned simply as part of identifying the RP, as when the tweet provides a more or less formal citation or the arguer locates the RP as a response to a previous pandemic. But the date of publication can factor into epistemic evaluation of RPs: based on the legitimate assumption that “scientific knowledge is open to revision in light of new evidence” (Next Generation Science Standards, 2013, p. 2), newer RPs can be taken to be epistemically better. Some arguers do use temporal indicators with this rationale. For example:

People are quoting this recommendation from the CDC—what are your thoughts on it? Its from 2006. The paper I sent you is from 2015 so more recent.

This was from 2015 but still a consideration. Cloth masks not recommended for clinical respiratory illnesses.

In the first tweet, the 2015 RP is positioned as better than the older one; in the second, the arguer is defending the “consideration” of the RP despite the fact that 2015 is not very recent. This sort of evaluation is surprisingly rare, however. Instead, a few arguers express dates as part of evaluating epistemic quality, but apply the opposite rule: older results are better, since they are well-established and time-tested:

Home made masks have been extensively tested for effectiveness and breath-ability for prevention of respiratory illnesses—since 2008.

And more frequent than either of these epistemic uses are the use of temporal indicators for social evaluations. Put simply, what did officials know, and when did they know it? “This is not new” is a frequent theme:

Amazing how the mask issue came up 14 years ago but nothing was done then. Look:

It was known in 2008 that masks work to reduce exposure to infections. The public has been lied to throughout this crisis.

By the way, this is research from 2015. So when millions more die from wearing cloth masks instead of procedural masks, don’t believe CDC when it backtracks and says it is due to “new” research. OLD RESEARCH proves that MEDICAL masks for everybody protect everybody.

Here the RPs are being used as evidence in a broader project of assessing social actors. But these social assessments can be turned around and used as evidence relevant to the authoritative quality of the RPs. Older articles can be deemed more trustworthy because they precede the current politicization of health agencies:

I don’t know what they were showing on MSNBC, but the CDC has a way to make it. To make you feel more comfortable it’s not trumps CDC, it’s the CDC from 2006.

The date of the RP is here considered important because of what it tells us about the credibility of the source: before Trump. Arguers, in sum, are more focused on social relations than on the nature of science. Taking use of temporal indicators as a test case thus confirms the analysis of the terms used to describe the RPs and the ways the RPs were used: arguers are assessing the authoritativeness more than the epistemic quality of RPs.

2.2 Authoritativeness

Arguers are assessing authoritativeness: how? In this section we explore in more detail the critical questions arguers are using–and not using–when they perform such assessments. As we will see, arguers do not put much effort into establishing the scientificness of the RPs or the qualifications of their authors. Instead, arguers focus on associating the RPs with institutions that have reputations for trustworthiness, and in probing for bias.

A first step in assessing the authoritativeness of some item will have to be to establish that it does in fact fall into the category of “science, research, study.” There are occasional mentions in the corpus of the obvious superiority of the RPs over the statements of non-scientists, and especially over other arguers on Twitter; e.g.:

I’ll just point you guys towards some studies that, you know, experts use rather than random social media.

Try reading the last sentence. Il trust real medical experts over Twitter know-it-alls.

However, this sort of boundary-work distinguishing experts from non-experts is relatively infrequent, possibly because the RPs which are the targets in this study were in fact conspicuously scientific (published in scientific journals, by authors with scientific credentials, in standard scientific formats) and thus required no defense.

Also largely absent from the corpus are efforts to bolster the credibility of the RP authors or journals. As seen in Table 17.2, author information of any kind was relatively infrequent. Authors are named almost exclusively as part of something like a citation; otherwise they are referred to vaguely by role terms such as “authors, scientists, researchers, doctors.” Journal information is offered more frequently. But examination of these references shows that they occur because arguers were using the share buttons on the RP source pages to autopopulate their tweets. Few tweets offer credentials for RP authors and none, impact factors for RP journals–the sorts of evidence that experts would use in assessing the authoritativeness of other experts and their statements.

Instead, what arguers do give attention to are “other entities” (Table 17.2) associated with the RP. In some cases, these “other entities” are likely mentioned just to identify a RP, as when the MacIntyre RP is described as “Vietnam/Vietnamese.” But in many cases, the “other entities” are ones with established, widely acknowledged reputations for scientific legitimacy. The US agencies National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control, the University of Cambridge, and PubMed are often named. This last is–correctly–noted as a trustworthy source for science:

When in doubt, go to the [National Library of Medicine news feed] and PubMed for evidence-based science and health information. I wondered about the efficacy of homemade masks. Don’t trust some bullshit blogger who isn’t a scientist; trust actual scientists.

The other three entities are similarly–but less correctly–put forward as associated with the RPs. “NIH” appears in large font in the header of the PubMed pages that many arguers linked to. Arguers took this association and ran with it. The Dato, MacIntyre and Van Der Sande RPs were each described as “NIH studies;” the Dato RP, with its useful mask recipe, was said to be “the NIH guide.” NIH was even positioned as the author of RPs:

NIH speaks. Last sentence. [Davies RP]

All of the Health Policy wonks keep saying that laymen don’t need masks and they’re of no value. The National Institutes of Health said differently in 2008. I think these doctors are only worried about dwindling supplies [Van Der Sande RP]

Or again: Cambridge University Press is the publisher of the journal where the Davies RP appeared, and is thus the prominently displayed owner of the website where some arguers found it. But arguers assert closer relationships, for example that Davies was “at Uni Cambridge.” These associations may be the result of confusion, but even the confusion is strategic. The Davies RP was also linked from ResearchGate, but ResearchGate is not mentioned in the corpus. Arguers appear to be looking for entities with known reputations as sources of trustworthy science and then bolstering the authoritativeness of the RPs by emphasizing whatever connections they can make (or make up) between those entities and the RPs.

In addition to paying attention to institutions with established reputations, arguers are sensitive to the potential for bias. Industry involvement in supporting or circulating the RPs is particularly suspect. Several arguers noticed, for example, that the mask producing company 3 M had funded the authors of the MacIntyre RP. Some arguers feel that this funding disqualified the RP:

So, I found this study really interesting until I saw that it was funded by 3 M.:rolling_eyes:

Original 2015 paper showing non-efficacy of cloth masks was funded by….drumroll…3 M

Shocked face that results show [health care practitioners] must buy 3 M products! Shocked face!

But other arguers read the small print at the end of the RP, and argued in support of the RP that 3 M had not been “involved in study design, data collection, or analysis.” Government funding, by contrast, is mentioned as a factor bolstering RP authoritativeness. At least if the government funding is from “the Netherlands Ministry of Health;” as we saw above in the discussion of temporal indicators, arguers found contemporary US agencies less credible. And in addition to bias through funding, distrust of partisanship was a consistent theme:

Trump’s @SurgeonGeneral flat out lied about the utility of masks. That is misinformation. And Trump’s CDC has been slow, inept, and bumbling at every stage of this crisis – they cannot be considered a neutral authority. Here’s some of the science:

Here’s a template from the CDC from years ago (when we could trust them)

This last combines identification of an entity with a known reputation and of that entity’s bias, integrating the two standards for assessing authoritativeness most common in the corpus.

2.3 Epistemic Quality

As argued above, epistemic evaluation of the RPs is relatively rare. But arguers do assert their right to do so, even as non-experts:

No medical degree required to read a study. [Canadian public health official] Tam is paid to know this. “Professional and Home-Made Face Masks Reduce Exposure to Respiratory Infections among the General Population”.

Oh hey! Lookie what I found on PubMed as a layman! “Our findings suggest that a homemade mask should only be considered as a last resort to prevent droplet transmission from infected individuals, but it would be better than no protection.”

The corpus shows that a few of the arguers making epistemic assessments pay attention to study type, sample size, and study recency. More focus on–but struggle with–the control group in the one RP that had one (MacIntyre), and with interpreting the significance of statistical results.

As one arguer notes, randomized controlled/clinical trials (RCTs) are “the gold standard of evidence in Medicine.” The one RCT among the six target RPs–the MacIntyre RP–drew the most attention (close to 40% of the corpus; Table 17.1); this may be in part driven by arguers’ sense that this study was indeed the best of the lot. Certainly many arguers implicitly align with the value of RCTs by using variations on that term when discussing the RP (Table 17.2), although the RP had made that easier by including the term prominently in both title and abstract. The fact that other RPs were not RCTs is asserted as a limitation in several cases, with one arguer offering the excuse:

You won’t get a real RCT experiment with COVID-19 though—it’s ethically impossible to do.

Other arguers highlight study size as important. The MacIntyre sample is several times described as “a rather large sample” or a “large RCT with thousands of patients [actually, healthcare practitioners],” although another arguer opines that “it’s not a massive cohort.” Sample size in the four RPs focused on design and fabric testing draws only one comment:

I am not a bio researcher but i find it strange that such a study only consist of two relative short experiments with only 28 and 22 people

Finally, as we saw above, a few arguers take the recency of a RP as an indicator of its epistemic quality.

Two other foci for epistemic evaluation are more prominent, but also more vexed: the control group and the significance of the statistical results, both from the MacIntyre RP. That study compared infection rates of health care workers wearing supplied medical masks, supplied cloth masks, or (the control) ordinary practice (which self-reports showed also involved masking). Arguers indicate the importance of the control group sometimes by explicitly mentioning it, and more often by implying its existence when expressing study results as a comparison. But they frequently get the comparison wrong; for example:

2015 study—cloth masks shown to be less effective than “no mask” control for healthcare workers.

You mean medical or surgical masks correct? Study showing that homemade cloth masks are worse than no mask (3 groups: med mask, cloth mask and no mask compared) is circulating and I think many are confused.

In response, a few arguers try to remedy the “confusion”, explaining that the control group of medical personnel used usual practice, which meant they were indeed masked:

The first RCT (2014) that looks at cloth vs. medical masks says “moisture retention, reuse of cloth masks and poor filtration may result in increased risk of infection”. But they didn’t use a no-mask control, so no evidence if it’s better than nothing.

Deleted my tweet because I was wrong and no need to keep bad info around. This study compares cloth masks to medical masks more rigorously, but doesn’t compare to no-mask control.

Overall, it appears that arguers understand that the control group is important for evaluating the epistemic quality of this RP but have trouble actually identifying it. Some arguers do get it right, and as the second tweet suggests, are able to share their insight with their interlocutors.

The interpretation of statistical results demonstrates the same pattern of recognized importance but difficulties with implementation. Information from the MacIntyre RP about permeability of materials provides a good example. In addition to running an RCT, this study subjected N95, surgical, and cloth masks to a standard test in which filter materials are challenged with aerosolized salt particles of sizes typical in industry, driven at a speed equivalent to heavy breathing. The abstract reports the results in this way: “Penetration of cloth masks by particles was almost 97% and medical masks 44%.” These statistics are highlighted in 132 (7%) of tweets linking to the RP, suggesting that arguers find them significant. Close to half of these tweets only quote the sentence; arguers that go beyond this to restate the statistics in their own words show a poor grasp of its meaning. Many drop the key term “particles,” speaking generally of “penetration” or “penetration rate.” This could be an adaptation to the brevity required by Twitter, but it might also indicate a failure to focus on penetration by what. The loss or misunderstanding of vital contextual information is explicit in other arguers’ summaries:

We abandoned a project after discovering that the masks allowed penetration of 97% of virus particles

I worry because there’s a study with pretty convincing numbers that cloth masks (which is all we have access to here) are ~97% ineffective? I’m not really sure what to do about it? I hate all of this. There’s just so much info to parse.

We realize this is a unique situation, but disinformation is criminal and dangerous. Like this push to wear homemade masks. laboratory-confirmed infections were significantly higher (97%) in cloth masks compared with the medical masks, (44%) #COVIDIOTS

“Particles” becomes “virus particles” or “virus,” and “penetration” becomes “ineffectiveness,” “risk,” or even “infection.” Only one arguer correctly points out that “97% penetration rate does not mean efficiency rate.”

In sum, while epistemic evaluation of the RPs is not prominent, arguers do show themselves sensitive to the importance of study type, sample size, and recency. They are also aware that they should pay attention to the control group and the significance of statistical results when assessing a RP, but they do not consistently demonstrate the capacity to interpret those correctly.

3 Relevance

As noted above, arguers’ interest in the RPs is pragmatic: they want to know what they can learn that will be useful in deciding whether cloth masks work and if so, what materials work best. Thus it should be no surprise to find that arguers show substantial strength in assessing the probative relevance (Blair, 2012) of the RPs to their information needs. Adjectives signaling (ir)relevance are frequent in the corpus (Table 17.2). The most prominent are general (“interesting, of interest; (really) important”), while others signal the RP is worth the investment of attention (“relevant, (possibly) useful, worth the read/a look”), because it upends assumptions (“wow, striking, remarkable, surprising”) or engages interests (“worrisome, concerning, scary, discouraging”). In assessing RP relevance, arguers pay attention to a variety of factors; here we will feature two prominent ones: inferences from one disease to another, and from one context to another.

Several arguers recognize that RPs focused on testing the efficacy of masks for past epidemics are of uncertain relevance to this newly emerging one. The difference in disease is thus sometimes introduced as a concession:

While this is NOT the flu, logic would indicate any shield / filter is better than none.

While not specific to Covid-19, this suggests a need to [re]-think current guidelines: Professional and Home-Made Face Masks Reduce Exposure to Respiratory Infections among the General Population

Other arguers defend relevance in less hesitant terms:

This is almost certainly a case of some PPE being better than none, and there is evidence to suggest efficacy from our experience with other viral illnesses:

The impact of wearing masks is known but no one seems to be aware. Even home made masks significantly reduce transmission. This peer-reviewed paper is not only applicable to SARS-CoV-1. It is also applicable to SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19.

Both these arguers propose similarities between the previous and present diseases: they are both “viral illnesses,” or even more closely, both variants of SARS-CoV.

There is also significant analysis of whether results obtained in labs or hospitals could be transferred to community settings. Some arguers think that study results are relevant despite differences in context:

One point I’ll mention Need to be somewhat [wary] of cloth masks This RCT in @bmj_latest suggests higher infection rates in HC workers (granted this is a healthcare setting)

Study of cloth masks in a surgical setting—cloth masks damp from breath facilitate infection. Why would that be different on the streets?

Notice that the last tweet presumes relevance, and challenges objectors to identify a significant difference. Other arguers are more cautious:

Another study by NIOSH found that cloth masks provided marginal protection against 20–1000nm particles: However, it’s important to note that none of these were conducted at a community level and examined community transmission.

These data in HCW prob should not be generalized to the public outside of hospitals, but they’re the data we’ve got and not so good…

This last arguer makes an appeal to ignorance: while it is dangerous to “generalize” results from a high risk situation to a low risk situation, we also need to lean into “the data we’ve got;” it is relevant by default until better studies can be done.

Other factors arguers noted as affecting study relevance include: the size of particles tested in comparison with the (then uncertain) size of particles transmitting the virus; the design, material, and usage of the tested mask; and efficacy for inward (self) protection versus outward (other) protection. Complex analyses would even integrate several of these factors; for example:

Totally inappropriate to use the linked study to assess cloth masks. It compared cloth masks in clinical settings against N95 to prevent HC workers from catching disease. What we care about is cloth masks’ ability to prevent people from spreading disease (+ limit virus in).

Overall, in contrast to arguers’ tendency to simply take the RPs as given without significant assessment of their premise adequacy, we see here evident sophistication as arguers reason about whether those premises are relevant to their interests in forming correct beliefs and adopting successful behaviors.

4 Sufficiency

We come finally to the ways arguers assess whether the RPs provide sufficient support for the conclusions they want to draw. The corpus shows that arguers are aware of a need to accumulate evidence. Many arguers proceed by offering multiple items in support of their conclusions; one fifth of the tweets include more than one link, ranging up to eight. Adjectives characterizing evidence sufficiency are also relatively frequent, primarily expressing sheer quantity: from “vast volume, numerous, many” through “several, limited” to “sole, not enough.” Arguers also note strength of support, again ranging along a spectrum from “conclusive, overwhelming, strong” to “weakly suggestive, wooly.” Beyond this, arguers show themselves particularly sensitive to the way that conflict between authorities reduces certainty. But they are less adept at managing the epistemic limitations and qualifications that all RPs include.

In line with dominance of assessment of authoritativeness, arguers are quick to note–or construct–the presence or absence of agreement among experts. Arguers signal their interest in con/dissensus with adjectives such as “pretty much all, mixed, non-consistent, conflicting;” they also explicitly discuss the topic. Some assert the existence of consensus, generally among vaguely identified “scientists”:

Frankly, we all DON’T know this. Studies show they have at least some efficacy. The general consensus among the science types is that the biggest benefit from wearing a mask is to reduce the chance that YOU’RE going to spread disease to someone ELSE.

Seems that scientists have found homemade masks offer some protection against the spread if worn by people who have the virus. Haven’t seen any academic saying they increase risks,. Here’s a link to @Cambridge_Uni Press study on homemade masks:

Other arguers note that authorities disagree–a more accurate view of the science of masking in the early months of 2020:

but there is also evidence cotton masks don’t protect on their own all that well. How do we figure this out?….legitimate experts say wildly different things.

everyone is like “listen to the experts” but which experts?? so many of them have different opinions.

For these arguers, the presence of disagreement among “legitimate experts” means that no conclusions can be justified–a troubling situation during a pandemic.

A very few arguers express careful assessments of sufficiency along more epistemic lines; for example:

The data is definitely limited, and yes suggest better than nothing (I suspect we’ve seen the same stuff) Eg: [four links]

AT BEST we can say that there’s very low quality evidence that highly adherent mask use may modestly reduce the likelihood of infection for people wearing them, although this has not been demonstrated in the majority of trials [two links].

Both these arguers concede that the “evidence”/”data” on masking is inadequate, in quantity or quality, and that only limited conclusions can be drawn from it (“suggest”… “may”). The second tweet shows even more sophistication in adding specific qualifications about the nature of mask use required (“highly adherent”) and the possible effect size (“modestly”). This degree of caution is warranted, given the paucity of studies, the range of unknowns (e.g., about how the virus was transmitted), and the complexity of relevant factors (mask design, materials, compliance, care).

So a few arguers do take note of the limited nature of the evidence on masking. Many more, however, ignore or overlook the limitations, sliding down the slippery slope into hype. Assertions that “masks (don’t) work” provide a convenient probe into the corpus. The Van Der Sande RP performed some standard tests of mask effectiveness with one style of homemade mask on a small number of volunteers: a study worthy of consideration, but hardly definitive. It is often reported, however, in unqualified terms:

There is a vast volume of science supporting case that masks work. Dutch scientists, PLoS One: “Any type of general mask use is likely to decrease viral exposure and infection risk on a population level, in spite of imperfect fit and imperfect adherence”

Research that’s shows general population mask use works. Most of it is ten years old and just waiting for some expert or official to “discover” it. I found it in 10 min.

As we saw above the MacIntyre RP focused on comparing the inward protection provided by cloth versus medical masks in hospital settings. But it is frequently presented as giving unqualified support to a conclusion about the ineffectiveness of masks in community settings, again expressed without reservations:

Cloth masks don’t work!!!!!!!!!! Stop Tweeting about the idiots making them! “Penetration of cloth masks by particles was almost 97%”

Cloth masks don’t work. That’s the tweet.

These arguments appear driven by confirmation bias; as one arguer noted, “U can find an article on the internet to repost for any position you have.” Thus while arguers show they understand the importance of seeking convergent lines of evidence, and are sensitive to (dis)agreements among authorities, they tend to assert unqualified conclusions, overemphasizing the amount of support the RPs in fact provide.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

This analysis has shown that Twitter arguers show significant skill in reasoning about research publications as authoritative sources, employing these critical questions:

-

Adequacy: Is the item science/research/a study?

-

Adequacy: Is the research publication associated with an entity with an established reputation for scientific legitimacy?

-

Adequacy: Is the research publication biased due to financial support or political affiliation?

-

Sufficiency: Do the experts agree about the conclusion?Footnote 5

In addition, we found a strong level of competence in assessing the relevance of research publications to information needs, and the quantitative sufficiency of RPs. While the specific factors arguers use to assess relevance are local to this case, the evidence suggests they are using generalized background principles:

-

Relevance: Is the situation reported in the research publication relevantly similar to the situation of interest?

-

Sufficiency: Are there enough research publications to support the conclusion?

By contrast arguers invest less attention in assessing the epistemic quality of research publications, and perform more poorly. When they did attend to epistemic quality, they were orienting to the following critical questions:

-

Adequacy: What is the quality of the kind of study reported by the research publication? [E.g., “gold standard” randomized controlled trials are better than observational studies..]

-

Adequacy: Is the sample size of the reported study enough to support its conclusion?

-

Adequacy: Is the study recent?

-

Adequacy: Does the comparison between treatment and control groups support the results reported by the study?

-

Adequacy: Do the statistical results of the study support its results?

-

Sufficiency: Does the study have significant limitations?

It might be tempting to jump from this poor performance to generalizations about public ignorance and vulnerability to misinformation during the “infodemic.” But before using these results about epistemic assessment to decry public scientific illiteracy, it is important to remember that assessing authority is a reasonable way to proceed in the face of significant epistemic asymmetry (Goodwin, 2010, 2011). Non-experts need to draw on expert knowledge. But their lack of expertise in a subject means that they also have limited abilities in applying the epistemic standards suitable for that subject. Not only do they not know much about a subject, they are not able to judge on epistemic grounds who is more expert in the subject, whether some procedures are good procedures in the subject and so on. By contrast, the ability to assess social standing is widespread. So nonexperts may be right to grant trust to entities with established reputations for scientific legitimacy, or even to a generalized “science” itself–provided those entities continue to deserve that trust.

It is also worth noting that our results represent a lower bound for the public’s capacity to assess research publications. Our corpus includes only the Twitter original posts mentioning the research publications. As work by Ye and Na (2018) suggests, reply threads are sometimes more sophisticated than the original posts, elaborating objections to and defenses of the research publications. Including this data would likely document a higher level of sophistication.

The areas of lower capacity revealed in this study have prescriptive implications, indicating the usefulness of specific interventions. Online reasoning support tools can emulate the excellent Understanding Health Research (n.d.) by implementing critical questions focused both on authoritative and epistemic assessment, supplemented by short explanations of the topics where additional scaffolding is most needed (here, control group and statistical results). At the institutional level, our results extend previous research showing that open access and relatively jargon-free research publications invite social media engagement (Ye & Na, 2018). In our corpus, over a third of tweets were conspicuously dependent on study abstracts (ABSTRACT, TOPIC, BRIEF SUMMARY). This suggests that plain language summaries adapted to address prevalent misunderstandings would be effective in improving assessment; more academic journals should require them.

The importance of institutional change points to the fact that our interest here is not just in fostering individual skill, but rather in enhancing society’s management of challenges like the pandemic. Success in addressing such complex, sociotechnical issues requires community-level science literacy (Roth & Barton, 2004; Snow & Dibner, 2016), including capacities to put scientific research to work through personal reasoning and interpersonal arguing. Previous studies have shown that publics do tweet about science (Didegah et al., 2018), and do draw from scientific research when participating in sociotechnical controversies (Endres, 2009; Kinsella, 2004). This study provides reason for further optimism. Despite the flaws in reasoning evident throughout the Twitter debate on masks, it is fair to say that the quality of attention was high. Previous studies of mentions of research publications on Twitter have found that rates of barebones tweets (LINK ONLY + TITLE) range from around 75% (for biomedicine) to 99% (for computer science; Kumar et al., 2019; Mejlgaard & Sørensen, 2018). In this pandemic-spurred debate over masking, by contrast, we found only 20% of tweets circulated a link or title without further comment. Our results confirm the early pandemic survey by Fang and Costas (2020); arguers, impelled by the urgency of the moment, were highly engaged in reasoning with each other.

The results of this study also provide some direction for the task of assessing the quality of such reasoning, i.e., for building what Sally Jackson has called a macroscope (Musi & Aakhus, 2018) for argument-focused community science literacy. Collective responses to the critical questions that emerged in the mask debate could be assessed by relatively “dumb” measures. For example, near collocation of the term “study” with named entities could establish what institutions are viewed as guaranteeing the trustworthiness of a research publication. The relative proportions of the terms “trial” (or similar), “study” and “science” could indicate more epistemic probing, the more they tilt towards the specific. Topic modelling could reveal the dimensions along which publication relevance is being assessed. And the critical questions identified in this study could be a starting point for a machine learning system–i.e., for “smarter” analyses.

But argument mining should aim to do more than just use Twitter as a convenient source of data about the argumentative capacities of a large number of individuals; automated analysis should characterize more than just the aggregate or average level of reasoning. Assessments of community science literacy should attend to the emergent properties of arguments at the system level (Goodwin, 2020), examining how and why the quality of public reasoning on a sociotechnical issue advances or decays through interactions among a large network of arguers (Howell & Brossard, 2021). That is, after all, the ultimate promise of deliberation as a privileged mode of democratic decision-making: deliberation produces something new (Manin, 1987). For example, although it would be easy to think of arguers on Twitter as “non-scientists,” that is not entirely accurate. Scientists are members of the tweeting public too. The authors of two of the research publications have tweets in the corpus, and we also find posts like this:

Original paper under discussion: “A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers” by Wang et al. (2015) Lots of potential confounders, but worth adding to the scale of consideration.

This arguer signals their expertise by following citation conventions and using the technical term “confounder” accurately. And such expert tweets spread through the wider network, as Fang and Costas (2020) noted–in contrast to the limited circulation of research publications in less exigent circumstances (Alperin et al., 2019). This suggests that to assess a truly community-level science literacy we will need to identify such high-expertise arguers (e.g., by scraping profile data), assess the connectedness of such experts to those with less expertise, and determine how the experts’ arguments are propagating through the network. Another signal of community science literacy could be found in what could be called “commonplace-ification.” As noted above, arguers may have been borrowing references to specific passages in the research publications from each other. Instead of thinking of such imitation as representing a decline in critical thinking, we should recognize that crystallization of an argumentative commonplace (topos) adds a handy new tool to the collective repertoire, enabling improved reasoning by many (Goodwin, 2020; Musi & Aakhus, 2018). Finally, in several tweets in the corpus–one quoted above–arguers confess to changing their minds in the face of correction from others. Explicit or implicit shifts in standpoint are another expected emergent property of a system of people making arguments; we need to be able to detect them.

Our results justify ending on a hopeful note, tempering some of the moral panic surrounding the “infodemic.” There is no evidence of “anti-science” in the corpus–no global distrust of scientific research, as opposed to warranted distrust aimed at specific targets. Instead, there was strong interest in scientific research publications, ample and vigorous probing, and lots of enthusiasm for applying research publications to the issues the pandemic had opened. While there was plenty of misinterpretation, there was also plenty of good reasoning, and even occasionally some changing minds. Public argument seems to have been doing its job for personal and policy decision-making; the argumentation research community can do its job by building the macroscopes, theories, and interventions that will support even better practice the next time around.

Notes

- 1.

In focusing on critical questions, we follow the widespread, pre-theoretical practice of supporting information users by explaining the factors they should consider when assessing sources (e.g., Understanding Health Research, n.d.; see Goodwin, 2012 for a broader review). Within argumentation studies, these factors have been theorized as deriving from the commitments undertaken in a given utterance, and therefore at the same time the lines along which that utterance can be called out (Jackson, 2019). In addition, some argumentation theorists have proposed clustering critical questions into determinate schemes of argument (Walton, Reed & Macagno, 2008) useful for both analytic and inventional purposes (Walton, 2005); although we note that other theorists have challenged this approach ().

- 2.

The pandemic year saw rapid expansion of research in this area; we now know that widespread use of facemasks is one important tool for slowing the spread of infection (Howard et al., 2021).

- 3.

Readers with a background in argumentation theory will notice that the more general term “adequacy” is here being substituted for the more common term “acceptability” to refer to the criterion for assessing premises. As Blair (2012, p. 76) notes, this is preferable in order to avoid imposing a theory of premise assessment before (in this case) seeing what principles are actual being used by arguers.

- 4.

For readability and to save space, the link to the target RP, links to other content, and most handles (“@Name”) have been stripped without ellipses. Emojis have been replaced with shortcodes. Errors are not marked, and are corrected only when they would impede understanding. Hard returns within tweets have been deleted; each paragraph here represents material from one tweet.

- 5.

This list diverges somewhat from the standard account of the argument scheme appeal to expert opinion (e.g., Walton et al., 2008). Both lists include bias and expert consensus. The standard account, however, insists on what we have been calling epistemic assessment, inviting users of the scheme to examine the expert’s expertise and the evidence the expert relied on. Arguers in this corpus did not apply these epistemic factors. Of course, critical questions about a defeasible scheme can be multiplied indefinitely. But if we take seriously the need to ground empirically the “core” critical questions which constitute a scheme, our results suggest that the standard account should be updated.

References

Alperin, J. P., Gomez, C. J., & Haustein, S. (2019). Identifying diffusion patterns of research articles on Twitter: A case study of online engagement with open access articles. Public Understanding of Science, 28(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662518761733

Battersby, M. (2010). Is that a fact? A field guide to statistical and scientific information. Broadview Press

Blair, J. A. (2012). Groundwork in the theory of argumentation: Selected papers of J. Anthony Blair. Springer

Bogomoletc, E., Goodwin, J. & Binder, A. (2021). Masks don’t work but you should get one: Circulation of the science of masking during the COVID-19 pandemic. In D.M. Berube (Ed.), Pandemic communication and resilience. Springer

Colavizza, G., Costas, R., Traag, V. A., van Eck, N. J., van Leeuwen, T., & Waltman, L. (2021). A scientometric overview of CORD-19. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0244839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244839

Didegah, F., Mejlgaard, N., & Sørensen, M. P. (2018). Investigating the quality of interactions and public engagement around scientific papers on Twitter. Journal of Informetrics, 12(3), 960–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.08.002

Endres, D. (2009). Science and public participation: An analysis of public scientific argument in the Yucca Mountain controversy. Environmental Communication, 3(1), 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524030802704369

Fang, Z., & Costas, R. (2020). Tracking the Twitter attention around the research efforts on the COVID-19 pandemic. ArXiv. arXiv:2006.05783 [cs.DL]

Goodwin, J. (1998). Forms of authority and the real ad verecundiam. Argumentation, 12(2), 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007756117287

Goodwin, J. (2010). Trust in experts as a principal-agent problem. In C. Reed & C.W. Tindale (Eds), Dialectics, dialogue, and argumentation (pp. 133–143). College Publications

Goodwin, J. (2011). Accounting for the appeal to the authority of experts. Argumentation, 25(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-011-9219-6

Goodwin, J. (2012). Accounting for the force of the appeal to authority. In F. Zenker (Ed.), Argumentation, cognition & community: Proceedings of the Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation Conference. Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA9/papersandcommentaries/10/

Goodwin, J. (2020). Should climate scientists fly? A case study of arguments at the system level. Informal Logic, 40(2), 157–203. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v40i2.6327

Hedonometer (n.d.). https://hedonometer.org/

Howard, J., Huang, A., Li, Z., Tufekci, Z., Zdimal, V., van der Westhuizen, H. M., ... & Rimoin, A. W. (2021). An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(4), e2014564118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2014564118

Howell, E. L., & Brossard, D. (2021). (Mis) informed about what? What it means to be a science-literate citizen in a digital world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(15), e1912436117. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1912436117

Jackson, S. (2019). Reason-giving and the natural normativity of argumentation. Topoi, 38(4), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-018-9553-5

Kinsella, W. (2004). Public expertise; A foundation for citizen participation in energy and environmental decisions. In S. Depoe, J. Delicath, & M.-F. Elsenbeer (Eds.), Communication and public participation in environmental decision making (pp. 83–95). SUNY Press

Kumar, M. S., Gupta, S., Baskaran, S., & Na, J. C. (2019). User motivation classification and comparison of tweets mentioning research articles in the fields of medicine, chemistry and environmental science. In A. Jatowt, A. Maeda, & S.Y. Syn (Eds.), Digital Libraries at the Crossroads of Digital Information for the Future (pp. 40–53). Springer

Manin, B. (1987). On legitimacy and political deliberation. Political Theory, 15(3), 338–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591787015003005

Musi, E., & Aakhus, M. (2018). Discovering argumentative patterns in energy polylogues: A macroscope for argument mining. Argumentation, 32, 397–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-017-9441-y

Next Generation Science Standards. (2013). APPENDIX H: Understanding the scientific enterprise: The nature of science in the Next Generation Science Standards. https://www.nextgenscience.org/resources/ngss-appendices

Paglieri, F. (2021). Less scheming, more typing: Musings on the Waltonian legacy in argument technologies. Journal of Applied Logics 8, 219–244. https://www.collegepublications.co.uk/ifcolog/?00043

Piwowar, H., Priem, J., Larivière, V., Alperin, J. P., Matthias, L., Norlander, B., Farley, A., West, J., & Haustein, S. (2018). The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of Open Access articles. PeerJ, 6, e4375. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4375

Roth, W. M., & Barton, A. C. (2004). Rethinking scientific literacy. Psychology Press

Saldanha, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage

Schünemann, H., Brożek, J., Guyatt, G., & Oxman, A. (2013). The GRADE Handbook. https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html

Snow, C., & Dibner, K. (Eds.). (2016). Science literacy: Concepts, contexts, and consequences. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/23595

Thomm, E., & Bromme, R. (2012). “It should at least seem scientific!” Textual features of “scientificness” and their impact on lay assessments of online information. Science Education, 96(2), 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20480

Understanding Health Research. (n.d.). https://www.understandinghealthresearch.org/

Walton, D. (2005). Justification of argumentation schemes. The Australasian Journal of Logic, 3, 1–13. http://www.philosophy.unimelb.edu.au/ajl/2005

Walton, D., Reed, C., & Macagno, F. (2008). Argumentation schemes. Cambridge University Press

Ye, Y. E., & Na, J. C. (2018). To get cited or get tweeted: A study of psychological academic articles. Online Information Review, 42(7), 1065–1081. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-08-2017-0235

Yeung, N., Lai, J., & Luo, J. (2020). Face off: Polarized public opinions on personal face mask usage during the COVID-19 pandemic. ArXiv. arXiv:2011.00336 [cs.CY]

Acknowledgements

This publication is based upon work from COST Action CA-17132, European Network for Argumentation and Public Policy Analysis (http://publicpolicyargument.eu), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). We would also like to thank Altmetric (Digital Science), for providing us with access to the Altmetric Explorer tool for data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Goodwin, J., Bogomoletc, E. (2022). Critical Questions About Scientific Research Publications in the Online Mask Debate. In: Oswald, S., Lewiński, M., Greco, S., Villata, S. (eds) The Pandemic of Argumentation. Argumentation Library, vol 43. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91017-4_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91017-4_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-91016-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-91017-4

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)