Abstract

End-to-end encryption has been a reality for at least 30 years. However, it is only with recent developments that it has become widespread on mobile phones operating over the internet. This has provided tools for terrorists to plan activities that lead directly to the deaths of innocent civilians. At the same time, it has also been used by dissidents challenging totalitarian regimes and holding liberal democracies to account. In this chapter I argue that while terrorist use of such encryption may render that encryption unjustifiable within a liberal democracy, within an international context the protection that it provides to those seeking to establish law-abiding democracies is too great to be ignored.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The encryption of messages, and subsequent attempts to decrypt the same by people other than the intended recipient, is an ancient practice [49]. Throughout the twentieth century, this became increasingly digitized as the Cold War and technological developments led to countries investing in increasingly complex methods of encryption, both in terms of hardware and software [5, 15]. With the introduction of the internet and the widespread use of smart mobile telephony, though, encryption has entered a new phase [4]. In the past, encryption by anyone other than a state actor has largely been a matter of amateur interest and ability, with most people lacking the mathematical skills and computing power to engage in complex cryptography. Recent developments, though, now mean that anyone in possession of a smart phone can encrypt their communications to a level of complexity matching that of many states’ own cryptographic agencies [19, 45].

These developments come at a price. What may be seen as the democratization of encryption can also be viewed as the protection of immoral activity, not least terrorism. To some degree, this protection has been limited by the technology available to the average person. For the most part, this has been “transport layer” encryption, such as Secure Socket Layer encryption (SSL—recognized online through URLs beginning “https://” vice “http://”). This functions by encrypting a message between sender and hosting platform, typically a website, which then decrypts the message. If the message is forwarded to a recipient other than the hosting platform, that host then re-encrypts the message and sends it on. Hence transport layer encryption allows a degree of encryption, but a hosting platform can always access the plain (decrypted) text of the message.

For example, if I were to send an unpublished, sensitive research paper to a colleague, I might use a web-based email service. These services are usually encrypted with SSL. By using this service, the paper would be encrypted on leaving my computer so that anyone intercepting my communications would be unable to read it. On reaching the email service’s web server, though, it would be decrypted and stored. When my colleague then opened her email to read the paper, it would then be re-encrypted by the server and sent to her computer. Thus, the paper is encrypted while in transit across the web, but not when it is at rest on my computer, my colleagues’ computer, or, perhaps most significantly, on the email service’s web server.

End-to-end encryption (E2EE), in contrast, cannot be read by anyone other than sender and intended recipient. The platform over which it is sent cannot access the content, thus guaranteeing an additional degree of protection for the secrecy of the message. E2EE frequently uses Public Key Encryption techniques in which sender and recipient each have a public and a private key through which they can encrypt and decrypt each other’s messages (e.g. Pretty Good Privacy—PGP).

Returning to the above example of sending a research paper over a web-based email service, I may decide that I am unhappy with the potential of that service being able to access and read my paper. Perhaps the paper is critical of that service, or it contains commercially sensitive information. In that case, I would encrypt it while it is still on my computer using a combination of a session key and my colleague’s public key, which is unique to her but publicly available. I could then send the encrypted paper to my colleague for her to decrypt using her private key, which, as the name suggests, is unique to her and not publicly available [32, 104]. In this way, the research paper remains encrypted while in transit across the web and while resting on the email service’s web server.

PGP is widely attributed to Phil Zimmermann, who developed it in 1991 [21, 32]. However, James Ellis, an employee at the UK signals agency GCHQ, developed the concept behind PGP in the 1970 but, due to the potential for abuse and the possibility of hostile actors having encryption which GCHQ was unable to decrypt, decided not to share it publicly [22, 23]. Even after Zimmermann popularised the concept, though, take-up of PGP was limited to those prepared to take the time and effort to understanding and implementing the approach. More recently, though, E2EE has been embraced by a number of applications, including Signal, Wickr, WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Zoom, iMessage, and Telegram. This has enabled E2EE to become far more widely implemented through a process largely invisible to the user, and thus requiring no more effort than using a non-encrypted app on a mobile phone.

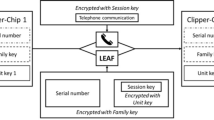

These concerns render E2EE an issue for national security and law enforcement, as ease of use entails the likelihood that such techniques will be employed by terrorists and other criminal actors. E2EE would render their communication secure from government interference, limiting the state’s capacity to identify and prevent attacks. Governments have responded by attempting to curtail the functionality of E2EE accordingly. In the mid-1990s, the Clinton administration responded to the introduction of PGP with a proposal for the “Clipper Chip”, which would provide a back door into encrypted communications for the state. That is, however good the encryption, the state would be able to access a master key which would break any encrypted media. Access to this “backdoor” into encrypted communications would be controlled by a trusted third party, holding the key in escrow. However, a significant public backlash in what became known as the crypto-wars led to the proposal being abandoned in 1996 [44, 52, 68].

In this chapter, I examine the evidence for terrorist use of E2EE and the counter-measures proposed by government. I then consider the debate in the standard terms of privacy versus security. This, though, leads to an undervaluing of the core interests that privacy protects, particularly security. After a brief discussion on the different aspects of security, I argue that there is a proportionality consideration that needs to be made in the E2EE debate. In conducting this, I conclude that while E2EE is arguably of less need in constitutionally robust and accountable liberal democracies, the international nature of digital communications mean that the loss of E2EE would endanger movements for democracy and the rule of law around the globe. This, I hold, is a price not worth paying.

2 Terrorist Use of E2EE

The concern regarding the threat posed by E2EE has traditionally been presented by the state in terms of terrorism [81, 85], and there is certainly evidence of terrorists using the technology.Footnote 1 In 2007, al Qaida created a custom-built encryption tool called “Mujahedeen Secrets”, which was known to be used in 2009 to communicate with Western-based operatives [89] and the use of which was taught to German recruits planning an attack in Europe the following year [14]. Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula cleric Anwar Al Awlaki devised his own custom encryption technique, which he used to communicate with Rajib Karim, a British Airways call centre worker in plotting the destruction of an aircraft and discussing the recruitment of further sympathisers [18].

With Islamic State (IS) the use of encryption turned from custom-made solutions to commercial off the shelf (COTS) products. While there is debate as to the degree to which encryption tools such as WhatsApp were instrumental in the plotting of major terrorist incidents, such as the Paris attacks in 2015, IS sympathisers have been reported as using a raft of COTS products, including Kik, PGP, Surespot, Tails, Telegram, Tor, TruCrypt, WhatsApp, and Zello, for their communications, including sharing beheading videos, developing networks, and proffering advice on how to hide one’s presence on the internet [29, 98]. Surespot was favoured by British IS operative Junaid Hussain to share bomb-making tips, and he is known to have used the tool to discuss targeting options with Junead Khan, another British extremist who was convicted of a plot to attack US military personnel in the UK [13, 17, 102]. Hussain also used an unspecified encryption system to communicate with a US sympathiser of IS who was in a group that shot at a “Draw the Prophet Mohammed” contest in Texas in May 2015, exchanging 109 encrypted messages on the day of the attack [38, 84].

It is therefore reasonable to conclude that terrorists are indeed using E2EE technologies, which provide “safe spaces” for them to communicate online. There is as yet no concrete public evidence of their having used these to plan major events, although this would be difficult to establish given the nature of the encryption. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the bulk of the publicly known use of E2EE by terrorist operatives, as opposed to their sympathisers, can be isolated to two users: Al Awlaki and Hussain. However, there is sufficient evidence to say that at least some terrorists have used E2EE to network and recruit people to their cause, and it is very likely that some have also discussed forthcoming attacks using the cloak of E2EE.

Assuming a broadly Lockean notion of a central responsibility of the state being to safeguard its citizens from attack, the concern of governments with terrorist use of E2EE is understandable. Essentially, governments are seen to fail in their primary responsibility every time a terrorist attack takes place in their territory. At the same time, we do not generally hold that the state has carte blanche to protect its citizens come what may. In liberal democracies at least, the state is rightly limited in its actions by human and civil rights which protect citizens from over-reach by the state. Furthermore, many if not most liberal democratic governments genuinely wish to protect their citizens’ rights and guard against overreach, for fear, if nothing else, of where this could lead with subsequent, less well-meaning governments. Hence, we do not generally see all-out assaults on every conceivable civic right by the state. However, E2EE is an effective way of guaranteeing the privacy of communications, and so responses to E2EE which involve governments reading, or being able to read, encrypted messages directly threaten the right to privacy. To this end, liberal democratic states have sought means of overcoming the limitations imposed by E2EE, such as through introducing a backdoor, while guaranteeing the privacy of citizens’ communications.

3 Countering E2EE

Arguments by the state for the insertion of backdoors such as the Clipper Chip into E2EE are clear, and have been made into law in some countries such as Australia [27]. However, once it is known that an encryption system has a backdoor this will render the system a likely target for attack by others, both malicious and security-minded actors seeking to find the backdoor and thereafter exploit or demonstrate it as a weakness in the system. Essentially, once there is a backdoor, it becomes very difficult to stop the “wrong” people gaining access. For this reason, Alex Stamos, former chief security officer at Yahoo, has likened backdoors to “drilling a hole in the windshield” such that the backdoor fatally undermines the integrity of the whole system [71]. This argument was used in 2015 when, following the San Bernadino terrorist shootings when the FBI took Apple to court in an attempt to force the technology company to provide a backdoor to its iPhones. Apple’s response was precisely that backdoors would be accessed and abused by malicious actors other than the state, and that the state itself was not entirely to be trusted. CEO Tim Cook argued that, “if a court can ask us to write this piece of software, think about what else they could ask us to write—maybe it’s an operating system for surveillance, maybe the ability for the law enforcement to turn on the camera … I don't know where this stops. But I do know that this is not what should be happening in this country” [28].

More recent attempts have been made to undermine the power of E2EE, notably but not exclusively in the US. These include the Eliminating Abusive and Rampant Neglect of Interactive Technologies (EARN IT) bill, introduced in March 2020 to the U.S. Senate by Republican Senator Lindsey Graham and Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal, and the Lawful Access to Encrypted Data (LAED) bill, introduced in June 2020 by Republican Senators Lindsey Graham, Tom Cotton and Marsha Blackburn. These are the latest incarnations of what has been dubbed Crypto-war 2.0, in reference to the earlier debate surrounding the introduction of PGP and the proposed Clipper Chip [44, 52, 68].

If EARN-IT is passed, companies would become liable for terrorist communications taking place over their platforms if it can be demonstrated that they failed to take adequate measures to protect against this. Allowing or encouraging E2EE could then be seen as precisely this sort of failure [3]. The LAED bill, if enacted, would “would authorize courts to issue search warrants that would compel ‘a device manufacturer, an operating system provider, a provider of remote computing service, or another person to furnish all information, facilities, and assistance necessary to access information stored on an electronic device or to access remotely stored electronic information, as authorized by the search warrant’” [67]. Hence Facebook, which owns WhatsApp, could be served a warrant to give unencrypted communications placed over WhatsApp to law enforcement. This would require Facebook to hold a backdoor to WhatsApp’s E2EE and so amounts to an effective repeat of the Clipper Chip debate.

As noted, these US efforts are not isolated cases. The LAED bill, if passed, would become the American equivalent of legislation which has existed in the UK since the passing of the Investigatory Powers Act in 2016 and in Australia since the passing of the Assistance and Access Act in 2018. However, US law carries somewhat greater force in this arena, given that so many technology companies are based in the US and come under US jurisdiction. By contrast, if these companies simply offer services in the UK and Australia but remain headquartered elsewhere, it becomes harder to enforce legislation demanding that the company breaks its own encryption.

If these bills are not passed in the US then E2EE remains, somewhat cynically, in the companies’ interests. This is because it allows them to avoid having to deal with government warrants and court orders which are passed to enable the state to forcibly access their content. It would enable technology companies to argue that, unlike SSL, with E2EE they are completely unable to access the content and so unable to comply with any such legal requirement for technical reasons. Furthermore, this would play well to customers who do not trust the state and seek encryption for legitimate communications which they wish to remain secret. To this end, it is notable that the Snowden revelations were a catalyst in encouraging the development of E2EE for public use, adding fuel to the fire for those who distrust state intentions in this area [101].

Even if the introduction of these laws is successful, though, as with the UK and Australia their impact will necessarily be limited in an international marketplace and on the internet. While the US may be able to regulate Facebook, for instance, many of the E2EE services known to be used by terrorists are free software that is openly available online. If any limitations were made to one service under a particular jurisdiction, the likely response by terrorists would be to switch to an alternative platform under a different (or no) jurisdiction [39]. This was raised in 1993, when cryptographer Whitfield Diffie testified to Congress that backdoors would weaken the value of US encryption providers in the global market. The known existence of backdoors in US encryption systems would raise suspicions among potential clients that the US government had access to their communications. Diffie added that those who wanted to hide their communications (i.e. terrorists) could still do so easily, even with such backdoors in place (such as through using code words to mask their activities). The result would be that the only people who would remain susceptible to state surveillance would be those who were not worried about that surveillance. Furthermore, once a backdoor is put in place, Diffie noted, there is no guarantee that others would not be able to exploit the backdoor for their own purposes [31]. Essentially, the same argument as we have seen Tim Cook was to give 23 year later.

Hence technical measures to provide backdoors into E2EE while guaranteeing citizen privacy are at least flawed and arguably impossible without fundamentally undermining the value of E2EE. It is not feasible to maintain E2EE while at the same time enabling governments to break the encryption in their efforts to counter terrorism. The technology is such that the ability for governments to break the encryption would risk legitimate users having their communications at risk of being intercepted by the state, while terrorists would evade discovery by resorting to alternative means of communication.Footnote 2

The public backlash to the Clipper Chip, Cook’s response to the FBI court case, and the catalysing effect of the Snowden revelations all point to the key problem for attempts to counter E2EE, namely that encryption provides a means for legitimate, non-malicious users to encrypt their communications for entirely moral reasons. To this end, appeal is frequently made to the right to privacy in the face of Government surveillance of communications [64], and so it is to an examination of privacy that I turn next.

4 Privacy and E2EE

Privacy is widely recognized as a core human right [25, 37, 83, 96], but it is a pro tanto rather than an absolute right. As described in human rights declarations and legislation, privacy may be overridden by competing considerations, such as national security and the public interest [62, 64]. Privacy is frequently recognized as a basic need, extending across time and cultures [58] which has both inherent and instrumental value [20, 63] in terms of protecting autonomy [7], governing relationships [78], freedom from embarrassment and freedom to be creative [35]. While each of these is often interpreted in terms of individual benefit, there are significant public benefits from privacy, and not only in terms of the aggregation of individual goods. Privacy is also central to the functioning of the democratic process and society at large [79, 80, 87, [91], and is therefore a key component of liberal democracies. As such, it should not be surrendered lightly.

At the same time, privacy is not a universal good. The claim to privacy can, most obviously, be used to cover illegal and immoral activities, such as planning acts of terrorism [74]. Given the uncontested evils of terrorism, it is hard to argue for the prima facie upholding of privacy in this case.Footnote 3

This is particularly true in the case of E2EE, given that a lack of E2EE (or a capability for the government to decrypt E2EE communications) does not automatically entail government mass surveillance, but rather allows for the possibility of government surveillance. Hence privacy is put at increased risk by banning or decrypting E2EE but not necessarily lost. The mere ability of the state to intercept and “read” the communications of its citizens does not automatically entail the actual interception and reading of these communications. This may seem like a fine distinction, but it is one which arguably means that the interception of communications which are then not read, or not read by a human, does not entail a violation of privacy [62, 64]. At the same time, there is ample evidence of liberal democratic states having done precisely this in the cases of Martin Luther King, Jr. [33, 66], the Democratic Party leading up to the 1972 US presidential election [24, 36], members of the UK Cabinet in the late 1970s [73], environmental groups in the UK in the 1980s and ‘90s [57], and Muslim groups in the US post-2001 [99]. None of these groups presented an obvious threat to national security, and yet their communications were accessed nonetheless.

Viewing the E2EE debate in terms of privacy versus security is therefore fraught with difficulty. While providing security is seen as one of the core duties of the state, privacy is a pro tanto right which can be overridden in the interests of national security. Furthermore, even if the state is able to ban or decrypt E2EE, it does not necessarily follow that privacy will be lost. The capacity to intercept and read people’s conversations does not necessarily lead to the actual interception and reading of those conversations. I have argued that an interest in privacy extends beyond the individual to the community and ultimately the state, but it is not obvious in and of itself that this interest should extend to allow acts of terrorism to be perpetrated.

To conclude that, in this instance at least, national security interests in countering terrorism should trump those of privacy would be too hasty, though. What is often missed in the privacy versus security debate is that another justification for privacy is that it provides security [60, 63]. While I have privacy, I have security from your (or the state’s) intrusion into my life, which is writ large when communities have privacy. This freedom from intrusion provides me/the community with significant security from interference by the state, as seen in the appeal made by numerous US Supreme Court judgments regarding the ability of the state to govern on activities normally engaged in the bedroom [90]. Furthermore, there is a question of distribution that is raised in the privacy vs security debate which can be missed. Precisely whose privacy is being infringed to protect exactly whom? Profiling of terrorist suspects on the basis of ethnicity or religion can often mean that the privacy of minority groups is imperilled while that of the majority remains untouched. This is particularly noteworthy in cases such as the police surveillance of Muslim groups [55, 56, 99] and environmental activists [57].

5 Security Versus Security

Rather than viewing the dilemma as one of privacy versus security, then, it may be more constructive to view it instead as one of security versus security. Within the context of counterterrorism, the term “security” is often taken as shorthand for “national security”, which gives it a strong force in arguments, such as when pitched against privacy. This is especially so in times of national crisis, such as when a state is facing a particular terrorist threat. However, national security is just one form of security. Waldron suggests three broad areas of collective security, national security and human security, while Herington identifies a range of uses, including national security, human security, ontological security, emancipatory security and securitization theory [42, 97, p. 459], to which could also be added social security, environmental security, maritime security and doubtless more. Despite this, there are commonalities in all these uses. National security is not so different from social or personal security in that there is a common denominator. Both entail an understanding of exposure to risk such that the greater the exposure, the less the security, and vice versa [65]. My proposal here is therefore to reframe the E2EE debate as concerning the security of the state against the security of the citizens of the state. In both cases, I take security to refer to the preservation of life (human security) and the preservation of a recognized way of life.

E2EE provides protection for citizen security, which may be threatened by individual agents/groups and/or by the state. The first of these, individual agents presenting a threat, may be serious hackers (possibly seeking to access personal details to engage in identity fraud) or amateur actors, such as abusive relatives or stalkers who want to spy on a person. Encrypted communications can help protect citizens from attacks from such actors. E2EE can also protect citizens qua corporations from a risk of cyberattack. By contrast, individuals and corporations as such are rarely threatened by acts of terrorism. This is not to say that individuals and corporations are not threatened by acts of terrorism—they are. However, terrorism is to a large extent indiscriminate. Beyond caring that the victims are the “right sort” of victim (i.e. citizens of a particular state), acts of terrorism are rarely directed at particular individuals. As such, E2EE can provide security to citizens against a directed, personalised threat while the loss of E2EE as a means of counterterrorism provides security to citizens against an undirected, impersonal threat.

The second threat to citizen security is from the state. In saying this, it should be remembered that there are more states than just liberal democracies. Totalitarian states clearly threaten the lives and wellbeing of their citizens, should those citizens dissent from the state’s activities. Given the international nature of the internet and encryption, the international audience must be considered in the equation. Furthermore, while liberal democracies generally do not threaten the lives and wellbeing of their citizens in the same way as totalitarian states, one of the reasons for this is inherent to the notion of liberalism: that citizens have rights against, and freedoms from, the state. Twentieth century history demonstrates how quickly the state can cease to be liberal or democratic when these rights are removed from citizens, as with the rise of Nazism in Germany and Soviet domination in mid-century Central Europe. It is therefore in the state’s interest to uphold these rights whenever possible.

The rights I have in mind here are those of free speech, free expression, free association, and the right to self-defence (human security). Each of these is recognised in the same international human rights legislation that recognize the human right of privacy. However, unlike privacy, these, and especially the right to self-defence cannot (at least as presented) be overridden by the public interest or national security. Furthermore, each of these rights is strengthened by E2EE. Without reliable encryption, any communications may be discovered and read by a government. While this may not be a concern for most domestic communication, even liberal democracies can have chilling effects on their citizens, while totalitarian states actively exploit chilling effects to control their citizens (Macnish [63], 35–37; Zizek [105], 135; [30]). The mere threat of the surveillance of communications can therefore prevent the activities of free speech/expression/association occurring, which is a detriment to the stability of liberal democracies and a mainstay of the stability of totalitarian regimes.

Through reframing the debate away from privacy versus security to that which privacy protects (security) versus security, the equation becomes less straightforward than it may at first have appeared. While privacy is a pro tanto right, the right to human security is absolute. This moves from a debate about competing values (privacy or security) to one about the same value. Through providing a common denominator we can now move forward to a proportionality calculation regarding E2EE and terrorism.

6 Proportionality

Considerations of proportionality as an element of moral philosophy date back at least as far as Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics [2, bk. V], and in general consideration to the biblical stipulation of “if there is serious injury, you are to take life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot” (Exodus 21: 23–24). In contemporary philosophy proportionality has been posited as a central component in the ethics of surveillance [40, 60, 82, 92], intelligence [6, 61, 70, 75], self-defence [95], and jurisprudential sentencing [86]. It also features in three aspects of the typical just war formulation: jus ad bellum, jus in bello, and the doctrine of double effect (DDE). In the form of DDE proportionality also enters discussions in medical ethics and any other area in which there are foreseeable but unintended harms (see, for example [10, 50, 76]). Appeal has been made to proportionality in writings as diverse as on the environment [88, 94], income distribution [9], investor interests [53], animal welfare [11], and computing [48]. It also sits behind everyday morality as we teach children how to respond to playground taunts and as we determine how to respond to neighbours who regularly play their music too loudly for our comfort.

Proportionality has also become a key consideration in laws regulating surveillance. In the UK, the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act [77] required acts of surveillance to be both necessary and proportionate [Section 28(2)], as does its replacement, the Investigatory Powers Act [47] [Section 61 (1c)]. In the US, the response of the Supreme Court in the case of Terry vs Ohio [392 U.S. 1 (1968)] elicited much discussion as to whether stop and search, within the context of the Fourth Amendment forbidding arbitrary search and seizure, merited a proportionate justification (see the discussion in [86], 1066–70). Proportionality is also a key consideration at the European level of both surveillance practices in general and counterterrorism in particular [16, 69].

Given this considerable breadth and history, proportionality has received comparatively little attention from analytic philosophers. The most notable exception is Thomas Hurka’s Proportionality in the Morality of War [46], from which my own Eye for an Eye: Proportionality and Surveillance [60] draws to clarify the role of proportionality in surveillance practice (although this approach has been challenged by [92], see also Rønn and Lippert-Rasmussen [82]). More recently still, Henschke has conducted an analysis of proportionality arguments used in the surveillance of metadata debate [40].

Henschke takes his analysis of proportionality beyond the appeal to fairness through balancing harms and benefits to suggest five ways in which the term is frequently used. The first of these, appropriateness, compares the means used with the end sought. In this case, an excessive means to achieve a given end (e.g. using armed police to break up a peaceful demonstration) is disproportionate. The second, action versus inaction, contrasts the act in question with not acting at all. If not acting would be relatively harmless then acting in a way that is harmful would be disproportionate. The third approach is that of comparing costs and benefits. In this case, the costs of doing an action are weighed against the benefits of that action. Fourthly, proportionality may be considered in terms of comparing alternative means to achieving a desired end. The least harmful means would then be the most proportionate, whereas any alternative would be disproportionate. Finally, Henschke suggests a fifth approach which compares simple with complex acts. A simple act (e.g. using armed police to break up a peaceful demonstration) may be excessive, but imagine that a group of known terrorists are using the cover of the demonstration to get sufficiently close to a civilian target with the aim of taking a number of hostages, and there was no alternative means of preventing this from happening. In that case, the use of armed police may not be disproportionate.

In the case of E2EE, the question of proportionality seems at first glance to fit the second approach of Henschke’s analysis more cleanly than any of the others. In this way the question can be framed as to whether leaving E2EE in place for common usage (i.e. doing nothing) will promote or enable terrorism over against banning or placing backdoors in E2EE systems. It seems that it would enable positive terrorist activities. Hence removing E2EE seems proportionate according to this approach. However, this conclusion would be too quick. There are also costs to banning E2EE systems, most notably in terms of removing communications security from those who justifiably seek it, such as dissidents persecuted by totalitarian regimes.

Hence the proportionality debate extends beyond a mere contrast between doing nothing and doing something (Henschke’s second formulation) to a comparison of costs and benefits (Henschke’s third formulation). The benefits of banning E2EE are increased national security in the face of terrorist threats. The costs are decreased personal security for those legitimate users of E2EE, some of whom may face very grave costs indeed. Within liberal democracies, there is a tendency among the majority to feel secure from their own government as a matter of course, thanks to constitutionally robust forms of accountability. As such, the threat of diminished security may not appear particularly great. However, that accountability may be less robust to some members of society (such as minorities in countries experiencing institutional racism in the police) than others. Furthermore, as I shall argue below, the global nature of digital communications in the internet age is such that the costs and benefits of E2EE must be seen to extend beyond the limits of the (liberal democratic) nation state.

7 Maintaining Perspective

It is important to recognize that some level of balance needs to be achieved in a liberal democratic society. While no-one wants a genuinely anarchic, Hobbesian state of nature to prevail in which the malicious can act on their own caprice, nor do citizens in liberal democracies seek to overthrow their governments in favour of totalitarian regimes that promise total security. There is a balance at the heart of liberal democracy that guarantees freedoms to all in order to prevent government abuse, but with the accompanying recognition that some (such as terrorists) will abuse those freedoms to undermine the very state that guarantees those freedoms.

I have suggested above that the rights in question in the E2EE debate are primarily different perspectives on security, but the very fact that they are perspectives is central. Take, for instance, the different perspectives of different people groups attempting to take a flight in the post-9/11 world. The perspectives of a person going through security to board a flight are likely to be radically different depending on the ethnicity and apparent religious beliefs of that person [51].

The importance of perspective has been picked up in the ethics of security literature by Jonathan Herington, who has identified three approaches to security: objective, subjective and affective [43]. Taking these in turn, objective security refers to the actual threat a person is under, irrespective of whether they are aware of the threat. For example, I may be about to walk over London Bridge, unaware that several men are planning to drive into people on the pavement and start stabbing them. In this case, I lack objective security, irrespective of my beliefs and feelings. Subjective security refers to the threat a person is aware of. Like objective security, it is a cognitive function: it is something which can be rationalised and argued for. I may be aware that there is a terrorist threat affecting my country. However, while I am aware of the threat (diminished subjective security) I am nowhere near any of the places planned for an attack, and so my objective security remains unaltered. Affective security, by contrast, is an emotive response concerning how secure a person feels, regardless of any facts of the matter. In this case, even though I may not be going near a place planned for attack, I may fear that I will be attacked. Equally, I may be going to a place which is the planned location for an attack but, like most in that situation, blissfully unaware of the tragedy that is about to unfold. Each of these is clearly important and each will lead to the individual (or group, for that matter) acting in different ways.

In the aforementioned case of ethnic profiling on flights, statistics clearly point to the fact that non-white members of ethnic minorities have been up to 42 times more likely to be subject to security searches than white people, and are hence less secure than white people in terms of objective, subjective and affective aspects [12, 51, 93]. Notably, such discrimination has been shown to push some members of ethnic minorities towards terrorism [72, 100]. Furthermore, even when such profiling has taken place, whether based on ethnicity or behaviour, it has been notoriously unsuccessful at identifying terrorists [59], and so its impact on objective security is negligible while the impact on subjective and affective security of those most affective is damaging to the extent of being counter-productive.

The consideration of differing perspectives is not motivated by a desire to see one person or groups perspective diminished as a “mere” perspective (as opposed to fact) but rather to recognize that in talking about balancing rights and interests, a key consideration is “whose rights” are under consideration. We have already encountered this above in considering the rights of citizens in liberal democracies versus those of citizens in totalitarian states. While I have argued that core human rights are important to people in both liberal democracies and totalitarian states, the reason for this importance is different accordingly. In a liberal democracy, society is free because those rights are recognised and upheld. Removing those rights threatens the ongoing stability of the nature of the state. By contrast, in a totalitarian state, dissidents have those rights in name only. They are typically persecuted for enacting those rights if they are caught doing so. Hence E2EE becomes a means of protecting the rights of citizens in liberal democracies and enabling or promoting the rights of citizens in totalitarian states.Footnote 4 While many considerations of proportionality are complicated through competing claims in different areas of rights,Footnote 5 in this case, the concern is more a matter of how to balance competing concerns regarding the right to security, albeit security from a number of different threats and understood from a number of different perspectives.

We should therefore approach the E2EE debate from (at least) two perspectives: the liberal democratic (domestic) and totalitarian (international).Footnote 6 Within the domestic perspective, there is a further differentiation that should be made between the perspective of those in the majority and those in minority groups. Objectively speaking, the threat of terrorism is severe and the overall need for communications to be kept secret from governments that practice self-restraint and are held constitutionally accountable (in practice as well as in principle) low. The objective security assessment may change, though, depending on the perspective of the person whose security is considered and on the actual level of accountability of the government in question. The affective security assessment, by contrast, will likely be radically different for someone who is in the majority group of that democracy than for someone in a minority group, particularly if that minority has suffered historical (and/or ongoing) injustices. As Henschke has pointed out, “It might be easy for me to say that this is the price I am willing to pay … when it is not me who is likely to bear the costs of misidentification” [41].

Were the domestic perspective the only perspective under consideration, the proportionality calculation would argue against E2EE, albeit that argument would require effective governmental self-restraint and effective accountability, particularly to minority groups. In such cases, E2EE is not strictly necessary, and to allow it would make life considerably easier for terrorists (as noted above). However, I have argued that the domestic perspective needs to be balanced with the international perspective. When this broader picture is considered, along with the potential to challenge totalitarian states, the balance is harder to determine. Nonetheless, the fact that democratic states are, as a rule, more law-abiding than their totalitarian alternatives suggests that within democracies there are alternative means to address terrorism and unjustified state surveillance [8]. By contrast, while totalitarian states are able to continue unthreatened by the people they oppress, they remain immune to their own laws and offer no alternative to those who seek change. As such, E2EE provides a crucial tool in the hands of those who would see democracy come to their own state and, though that, fight abuse and lawlessness.

8 Conclusion

In this chapter I have argued that end-to-end encryption (E2EE) presents a fundamental challenge to liberal democratic governments. Communications over E2EE are not accessible to state security services. Hence when terrorists use E2EE, and I have shown that they do, they do so with security. The ongoing existence of E2EE thus indirectly threatens one of the basic responsibilities of the liberal democratic state: the national security of that state. To regain the upper hand in providing security over and against terrorists, liberal democratic states have attempted to challenge E2EE. However, their attempts to do so have been seen to be flawed and ineffective. Furthermore, these attempts come at the expense of citizen privacy.

Privacy is a core value, I have argued, in protecting individuals from the state. However, it is widely recognized as a pro tanto value which may be overridden by national security concerns. As such, arguments in favour of privacy which threaten national security may not be convincing, despite the democratic value of privacy.

I have argued that a stronger approach is to look beyond privacy to that which privacy protects, which in this case is the security of the citizen. In this way, national security is weighed against the collected interests of citizen security. This allows for a proportionality calculation to be made. I suggested that while the relevant proportionality calculation appears to be doing something (banning E2EE) over doing nothing, the correct calculation in fact involves weighing the benefits of acting (banning E2EE) over the costs of losing E2EE.

In the case of constitutionally robust and genuinely accountable liberal democratic societies, I argued that there is a morally legitimate security need for private communication, but that this may be overridden by the threat to national security posed by terrorism. Even so, the perspective one takes on this may change depending on how secure within the state one is and feels. However, when taking an international perspective which includes the citizens of totalitarian states, the value of E2EE is considerable in providing a tool for establishing democracy. Given that we live in a world of global communications, it is both unlikely that E2EE can be stopped and it is desirable that we should not want it to be stopped. Terrorism may be the ultimate price that we have to pay for that freedom of others.

Notes

- 1.

Note that I am here taking “terrorism” at face value to be an indiscriminate threat to civilian life, rather than a cynical labelling in international politics used to distinguish friends from enemies.

- 2.

It is also worth pointing out that while it is a significant loss for security services to be unable to access the content of terrorist communications, they retain the in principle ability to perform network analysis on the metadata of these communications. Furthermore, traditional methods of deterrence and investigation continue, and continue to be effective. It would be short-sited to see the breaking of E2EE as the only means to defeat terrorism.

- 3.

- 4.

The decision matrix introduced by Jonathan [103] and employed by myself (2016b, 11) in considerations of threats to privacy and security is relevant here. If the surveillant has an interest in the surveillance going ahead and the wrongs of that surveillance will be visited on another, then the surveillant will likely be risk prone: in taking the risk, he suffers no loss (that falls to someone else). Where this is the case, redress can be found through imposing losses on the surveillant. This may arise through the imposition of fines on the surveillant, for example. In this way, when deciding whether to employ surveillance, the surveillant must factor his own loss into the equation.

- 5.

In his historical overview of the principle of proportionality, Eric Engle traces the idea of justice as proportionality to Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics, where it refers to ratio, “the right relationship … between the state and the citizen, adjudicated by the rule of law” ([26], 4). The concept of proportionality then developed through the medieval period via discussions of self-defence and war until Grotius introduced, “the union of the ancient concept of justice as ratio, the medieval concept of proportionate self-defence, and the modern concept of balancing interests" ([26], 5). Engle then goes some way to undoing this Grotian union, distinguishing proportionality (which he defines as means end testing in terms of inalienable rights) from balancing (which he sees as being cost benefit analysis regarding alienable rights) ([26], 10).

- 6.

Obviously, there are international liberal democratic regimes as well. However, I take the issues for them to be the same as the domestic liberal democratic regime.

References

Allen AL (1988) Uneasy access: privacy for women in a free society. Totowa, N.J: Rowman & Littlefield

Aristotle, Barnes J (2004) The Nicomachean ethics. Edited by Hugh Tredennick. Translated by JAK Thomson. New Ed edition. Penguin Classics, London, England; New York, N.Y.

Baker S (2020) A new twist in the endless debate over end-to-end encryption. Reason.Com (blog). 11 Feb 2020. https://reason.com/2020/02/11/a-new-twist-in-the-endless-debate-over-end-o-end-encryption/

Bamford J (2009) The shadow factory: the ultra-secret NSA from 9/11 to the eavesdropping on America: The NSA from 9/11 to the eavesdropping on America. Random House Inc., New York

Bamford J (1982) The puzzle palace: a report on NSA, America’s Most Secret Agency. 5th THUS. Houghton Mifflin

Bellaby RW (2014) The ethics of intelligence: a new framework. Routledge, London, New York

Benn S (1971) Privacy, freedom, and respect for persons. In: Pennock J, Chapman R (eds) Nomos XIII: privacy. Atherton Press, New York

Bobbitt P (2009) Terror and consent: the wars for the twenty-first century. Penguin, London

Cappelen AW, Tungodden B (2017) Fairness and the proportionality principle. Soc Choice Welfare 49(3–4):709–719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00355-016-1016-6

Cavanaugh TA (2006) Double-effect reasoning: doing good and avoiding evil. Oxford studies in theological ethics. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Cheyne I, Alder J (2007) Environmental ethics and proportionality: hunting for a balance. Environ Law Rev 9(3):171–189. https://doi.org/10.1350/enlr.2007.9.3.171

Choudhury T, Fenwick H (2011) The impact of counter-terrorism measures on Muslim communities. Int Rev Law Comput Technol 25(3):151–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2011.617491

Coker M, Yadron D, Paletta D (2015) Hacker Killed by Drone Was Islamic State’s “Secret Weapon”. Wall Street J. 27 Aug 2015, sec. World. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hacker-killed-by-drone-was-secret-weapon-1440718560

Cruickshank P (2013) Did NSA leaks help al Qaeda? CNN security blogs (blog). 25 June 2013. https://security.blogs.cnn.com/2013/06/25/did-nsa-leaks-help-al-qaeda/

Davies D (1997) A brief history of cryptography. Inf Secur Tech Rep 2(2):14–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1363-4127(97)81323-4

De Hert P (2005) Balancing security and liberty within the European human rights framework. A critical reading of the court’s case law in the light of surveillance and criminal law enforcement strategies after 9/11 special issue on terrorism. Utrecht Law Rev 1(1):68–96

Dearden L, Sandhu S (2016) Luton delivery driver found guilty of preparing for UK terror attack. The Independent. 1 Apr 2016. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/junead-khan-luton-delivery-driver-found-guilty-preparing-uk-terror-attack-american-forces-a6963451.html

Dodd V (2011) British airways worker Rajib Karim convicted of terrorist plot. The Guardian. 28 Feb 2011, sec. UK news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2011/feb/28/british-airways-bomb-guilty-karim

Dooley JF (2018) History of cryptography and cryptanalysis: codes, ciphers, and their algorithms, 1st edn. Springer

Doyle T (2009) Privacy and perfect voyeurism. Ethics Inf Technol 11:181–189

Dubrawsky I, Faircloth J (2007) Security + study guide. Syngress

Ellis JH (1970) The possibility of secure non-secret digital encryption. UK Commun Electron Secur Group 6

Ellis JH (1987) The story of non-secret encryption. https://cryptome.org/jya/ellisdoc.htm

Emery F (1995) Watergate. Simon and Schuster

Engel C (2001) The European charter of fundamental rights a changed political opportunity structure and its normative consequences. Eur Law J 7(2):151–170

Engle E (2012) The history of the general principle of proportionality: an overview. Dartmouth Law J 10:1

Farivar C (2018) Australia passes new law to thwart strong encryption. Ars Technica. 12 June 2018. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2018/12/australia-passes-new-law-to-thwart-strong-encryption/

Francis E (2016) Exclusive: Apple CEO Tim Cook says IPhone-cracking software “equivalent of cancer”. ABC News. 24 Feb 2016. https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/exclusive-apple-ceo-tim-cook-iphone-cracking-software/story?id=37173343

Frankel S (2016) This is how ISIS uses the internet. BuzzFeed News. 12 May 2016. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/sheerafrenkel/everything-you-ever-wanted-to-know-about-how-isis-uses-the-i

Funder A (2004) Stasiland: stories from behind the Berlin Wall. New edition. Granta Books

Gallagher S (2019) Barr says the US needs encryption backdoors to prevent “Going Dark.” Um, What? Ars Technica. 8 Apr 2019. https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2019/08/post-snowden-tech-became-more-secure-but-is-govt-really-at-risk-of-going-dark/

Garfinkel S (1995) PGP: pretty good privacy. O’Reilly Media, Inc.

Garrow DJ (2015) The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr.: from ‘Solo’ to Memphis. Open Road Media

Gavison R (Nov. 1992) Feminism and the public/private distinction. Stanford Law Rev. 45(1):1–45

Gavison R (1984) Privacy and the limits of the law. In: Schoeman FD (ed) Philosophical dimensions of privacy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 346–402

Genovese MA (1999) The watergate crisis. Greenwood Publishing Group

Grabenwarter C (2014) European convention on human rights. In: European convention on human rights. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG

Graham R (2016) How terrorists use encryption. CTC Sentinel 9(6):20–25

Graham R (2019) Why we fight for crypto. 28 July 2019. https://blog.erratasec.com/2019/07/why-we-fight-for-crypto.html

Henschke A (2018) Are the costs of metadata worth it? Conceptualising proportionality and its relation to metadata. In: Baldino D, Crawley R (eds) Intelligence and the function of government. Melbourne University Press

Henschke A (2019) Information technologies and constructions of perpetrator identities. In: Goldberg Z, Knittel S (eds) Routledge handbook on perpetrator studies. Routledge, London

Herington J (2012) The concept of security. In: Michael S, Christian E (eds) Ethical and security aspects of infectious disease control: interdisciplinary perspectives. Ashgate, pp 7–26

Herington J (2015) The concept of security, liberty, fear and the state

Hoffman LJ (ed) (1995) Building in big brother: the cryptographic policy debate. Springer-Verlag, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-2524-9

Holden J (2018) The mathematics of secrets: cryptography from caesar ciphers to digital encryption. Illustrated Edition. Princeton University Press

Hurka T (2005) Proportionality in the morality of war. Philos Publ Aff 33(1):34–66

IPA (2016) Investigatory powers act. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2016/25/contents/enacted

Iachello G, Abowd GD (2005) Privacy and proportionality: adapting legal evaluation techniques to inform design in ubiquitous computing. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. ACM, CHI’05. New York, NY, USA, pp 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1145/1054972.1054986

Kahn D (1997) The Codebreakers: the comprehensive history of secret communication from ancient times to the internet, 2nd edn. Scribner, New York

Kamm FM (1991) The doctrine of double effect: reflections on theoretical and practical issues. J Med Philos 16(5):571–585. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/16.5.571

Khaleeli H (2016) The perils of “flying while Muslim”. The Guardian. 8 Aug 2016, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/08/the-perils-of-flying-while-muslim

Koops B-J, Kosta E (2018) Looking for some light through the lens of “cryptowar” history: policy options for law enforcement authorities against “going dark.” Comput Law Secur Rev 34(4):890–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2018.06.003

Krommendijk J, Morijn J (2009) “Proportional” by what measure(s)? Balancing investor interests and human rights by way of applying the proportionality principle in investor-state arbitration. In: Dupuy P-M, Petersmann E-U, Francioni F (eds) Human rights in international investment law and arbitration. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 421–55. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2333550

Lever A (2005) Feminism, democracy and the right to privacy. SSRN Scholarly Paper, ID 2559971, Social Science Research Network. http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2559971

Lewis P (2010a) Legal fight over spy cameras in Muslim Suburbs. The Guardian. 11 June 2010, sec. UK news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/jun/11/project-champion-numberplate-recognition-birmingham

Lewis P (2010b) Birmingham stops camera surveillance in Muslim areas. The Guardian. 17 June 2010, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/jun/17/birmingham-stops-spy-cameras-project

Lewis P, Evans R (2013) Undercover: the true story of Britain’s secret police. Faber & Faber

Locke JL (2010) Eavesdropping: an intimate history. OUP Oxford

Macnish K (2012) Unblinking eyes: the ethics of automating surveillance. Ethics Inf Technol 14(2):151–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-012-9291-0

Macnish K (2015) An eye for an eye: proportionality and surveillance. Ethical Theory Moral Pract 18(3):529–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-014-9537-5

Macnish K (2016a) Persons, personhood and proportionality: building on a just war approach to intelligence ethics. In: Galliott J, Reed W (eds) Ethics and the future of spying: technology, national security and intelligence collection. Routledge

Macnish K (2016b) Government surveillance and why defining privacy matters in a post-Snowden world. J Appl Philos.https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12219

Macnish K (2018) The ethics of surveillance: an introduction, 1 edn. Routledge, London, New York

Macnish K (2020) Mass surveillance: a private affair? Moral Philos Polit 1 (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1515/mopp-2019-0025

Macnish K, van der Ham J (2021) Cybersecurity ethics. In: OUP handbook on digital ethics. Oxford University Press. Oxford

Martin L (2018) Bureau Clergyman: how the FBI colluded with an African American televangelist to destroy Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Relig Am Cult 28(1):1–51. https://doi.org/10.1525/rac.2018.28.1.1

McKay Tom (2020) Three GOP senators introduce bill experts say would basically ban end-to-end encryption. Gizmodo. 24 June 2020. https://gizmodo.com/three-gop-senators-introduce-bill-experts-say-would-bas-1844157194

Meinrath SD, Vitka S (2014) Crypto war II. Crit Stud Media Commun 31(2):123–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2014.921320

Michaelsen C (2010) The proportionality principle, counter-terrorism laws and human rights: a German-Australian comparison. City Univ Hong Kong Law Rev 2(1):19–44

Omand D (2012) Securing the state. Hurst, London

Perlroth N (2019) What is end-to-end encryption? Another bull’s-eye on big tech. The New York Times, 19 Nov 2019, sec. Technology. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/19/technology/end-to-end-encryption.html

Piazza JA (2012) Types of minority discrimination and terrorism. Confl Manag Peace Sci 29(5):521–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894212456940

Pincher C (1978) Inside story: a documentary of the pursuit of power, 1st edn. Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd., London

Posner RA (2008) Privacy, surveillance, and law. Univ Chicago Law Rev 75(1):245–260

Quinlan M (2007) Just intelligence: prolegomena to an ethical theory. Intell Nat Secur 22(1):1–13

Quinn WS (1989) Actions, intentions, and consequences: the doctrine of double effect. Philos Public Aff 18(4):334–351

RIPA (2000) Regulation of investigatory powers act. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/23/data.pdf

Rachels J (1975) Why privacy is important. Philos Public Aff 4(4):323–333

Regan PM (1995) Legislating privacy: technology, social values, and public policy. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill

Roessler B, Mokrosinska D (eds) (2015) Social dimensions of privacy: interdisciplinary perspectives. Cambridge University Press, New York

Rudd A (2017) We don’t want to ban encryption, but our inability to see what terrorists are plotting undermines our security. The Telegraph, 31 July 2017. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/07/31/dont-want-ban-encryption-inability-see-terrorists-plotting-online/

Rønn KV, Lippert-Rasmussen K (2020) Out of proportion? On surveillance and the proportionality requirement. Ethical Theor Moral Pract:1–19

Sacerdoti G (2002) The European charter of fundamental rights: from a nation-state Europe to a citizen’s Europe. Colum J Eur L 8:37

Sanger DE, Perlroth N (2015) F.B.I. Chief Says Texas Gunman used encryption to text overseas terrorist. The New York Times. 9 Dec 2015, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/10/us/politics/fbi-chief-says-texas-gunman-used-encryption-to-text-overseas-terrorist.html

Severson D (2017) The encryption debate in Europe. Hoover Institution Aegis Paper Series, no 1702

Slobogin C (1998) Let’s not bury terry: a call for rejuvenation of the proportionality principle. John’s L Rev 72:1053

Solove DJ (2002) Conceptualizing privacy. Calif Law Rev 90(4):1087–1155

Steel D (2013) Precaution and proportionality: a reply to turner. Ethics Policy Environ 16(3):344–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2013.844572

Storm M, Cruickshank P, Lister T (2014) Agent storm: my life inside al-Qaeda. Penguin

Supreme Court (2003) Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003). US Supreme Court

Taylor L, Floridi L, van der Sloot B (eds) (2016) Group privacy: new challenges of data technologies, 1st edn. (2017). Springer

Thomsen FK (2020) The teleological account of proportional surveillance. Res Publica:1–29

Travis A (2016) David Miranda ruling throws new light on schedule 7 powers. The Guardian. 19 Jan 2016, sec. UK news. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jan/19/david-miranda-ruling-throws-new-light-on-schedule-7-powers

Turner D (2013) Proportionality and the precautionary principle. Ethics Policy Environ 16(3):341–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/21550085.2013.844571

Uniacke S (2011) Proportionality and self-defense. Law Philos 30(3):253–272

United Nations (1948) The universal declaration of human rights. 10 Dec 1948. http://www.un.org/en/documents/udhr/index.shtml

Waldron J (2006) Safety and security. Nebr. Law Rev. 85

Warrick J (2016) The “App of Choice” for Jihadists: ISIS seizes on internet tool to promote terror. Washington Post. 23 Dec 2016, sec. National Security. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/the-app-of-choice-for-jihadists-isis-seizes-on-internet-tool-to-promote-terror/2016/12/23/a8c348c0-c861-11e6-85b5-76616a33048d_story.html

Wasserman MA (2015) First amendment limitations on police surveillance: the case of the Muslim surveillance program notes. New York Univ Law Rev 90(5):i–1826

Welch K (2016) Middle Eastern terrorist stereotypes and anti-terror policy support: the effect of perceived minority threat. Race Justice 6(2):117–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/2153368715590478

Whittaker Z (2018) Five years after Snowden: what changed? ZDNet. 6 June 2018. https://www.zdnet.com/article/edward-snowden-five-years-on-tech-giants-change/

Wilber DQ (2017) Here’s how the FBI tracked down a tech-savvy terrorist recruiter for the islamic state. Los Angeles Times. 13 Apr 2017. https://www.latimes.com/politics/la-fg-islamic-state-recruiter-20170406-story.html

Wolff J (2010) Five Types of risky situation. Law Innov Technol 2(2):151–163. https://doi.org/10.5235/175799610794046177

Zimmerman PR, Ludlow P (1996) How PGP works/why do you need PGP. The MIT Press Cambridge

Zizek S (2009) Violence: six sideways reflections. First Paperback Edition. Profile Books

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Macnish, K. (2021). An End to Encryption? Surveillance and Proportionality in the Crypto-Wars. In: Henschke, A., Reed, A., Robbins, S., Miller, S. (eds) Counter-Terrorism, Ethics and Technology. Advanced Sciences and Technologies for Security Applications. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90221-6_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90221-6_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-90220-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-90221-6

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)