Abstract

This contribution analyses the relationship between the rule of law and labor productivity growth by businesses within an EU country sample over the period 1998–2005. It finds that the rule of law affects labor productivity growth (LPG) by businesses within the EU via two distinct channels. First, the rule of law positively affects labor productivity growth by stimulating total factor productivity (TFP) growth. Second, the rule of law positively influences business investments in intangible capital. The author concludes that the rule of law is beneficial in facilitating an economy’s transformation towards becoming a knowledge economy.

Originally published in: Felix Roth. The Rule of Law and Labor Productivity Growth by Businesses: Evidence for the EU, 1998–2005. European Commission, DG Joint Research Centre, Project Report, No. 258747, 2014.

The author wishes to thank Sjoerd Hagemann, Raf van Gestel, Leandro Elia, Michaela Saisana, and Andrea Saltelli for their valuable comments. The paper received funding from the European Commission’s DG Joint Research Centre.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

JEL Classifications

Keywords

1 Introduction

The academic literature (Barro, 2001, p. 13; Knack & Keefer, 1995, p. 210), as well as policymaking institutes (European Commission, 2013a, p. 1, World Bank, 2006, pp. 87–99) and non-profit organizations (Agrast et al., 2013, p. 8) have stressed that respect for the rule of law constitutes a prerequisite for a nation’s economic performance. In this context, the European Commission recently claimed that in the EU “the quality (…) of national justice systems plays a key role in restoring (…) the return to growth” (European Commission, 2013a, p. 1). Given this prominent claim by the European Commission and the fact that economic empirical literature focuses strongly on the dichotomy between developed and developing economies (see among others Acemoglu et al., 2001; Barro, 2001; Easterly & Levine, 2003; Hall & Jones, 1999; Kaufmann & Kraay, 2002; Knack & Keefer, 1995; Rigobon & Rodrik, 2005; Rodrik et al., 2004; c.f. World Bank 2006, p. 4, pp. 96–99), this contribution’s aim is to assess the relationship between the rule of law and a country’s economic performance in an EU context.

In this respect, it can be claimed, that the economies of most EU member states, similar to those of the US (Corrado et al., 2005, 2009; Nakamura, 2010) and other highly developed economies, such as Japan (Fukao et al., 2009), are on the verge of evolving into knowledge economies (Piekkola 2011). This claim is substantiated by empirical evidence, which highlights that in some EU countries such as France, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, business intangible capital investments already represent two-thirds made in tangible capital investment. Similarly, when accounting for labor productivity growth of businesses in the EU, the growth of intangible capital services explains a larger share (50%) than the growth of tangible capital services (40%) (Roth & Thum, 2013). Given these and other most recent empirical findings, which underline the importance of intangible capital investment for labor productivity growth in the EU (Marrano et al., 2009; Edquist, 2011), this contribution utilizes an intangible capital-enhanced production model as introduced by Roth and Thum (2013) to explore the relationship between the rule of law and labor productivity growth by businesses in the EU. Following the existing literature (Benhabib & Spiegel, 1994; Knack & Keefer, 1995), this contribution identifies two main theoretical channels of how the rule of law might affect labor productivity growth by businesses. First, the rule of law might directly influence labor productivity growth by businesses via its TFP component. Second, the rule of law might influence labor productivity growth indirectly via its impact on business investments in tangible and intangible capital.

This study is structured in the following manner: The second section explores the theoretical links between the rule of law and labor productivity growth and identifies two transmission channels through which the rule of law affects a country’s labor productivity growth by businesses. The third section introduces the model specifications for the two main theoretical channels and elaborates upon the research design, the operationalization of the rule of law and the data sources used. The fourth section carries out a descriptive analysis of the distribution of the rule of law across an EU-27 country sample and the bivariate relationship between the rule of law and intangible and tangible capital investments. The fifth section undertakes an econometric analysis of the relationship between the rule of law and labor productivity growth by businesses, as well as the rule of law and business investments in tangible and intangible capital. The last section presents the main findings, discusses the empirical findings in light of the theoretical discussion and offers policy conclusions.

2 The Rule of Law and Labor Productivity Growth by Businesses: Theoretical Links in an EU Context

Although final agreement on precisely what constitutes the rule of law has yet to be established (Botero & Ponce, 2011, p. 2), the academic literature in the general social sciences has identified four theoretical links through which the rule of law is associated with economic growth: namely 1) the provision of the personal security of individuals, 2) the security of property and enforcement of contracts, 3) institutional checks on government, and 4) control of private capture and corruption (Haggard & Tiede, 2011, pp. 674–75). Within these four theoretical links, the economic literature has identified the security of property and enforcement of contracts as one of the core theoretical links through which the rule of law affects economic growth (Haggard & Tiede, 2011, p. 675). The preeminence of the security of property rights and the enforcement of contracts within the discipline of economics has been theoretically elaborated upon by classical economic thinkers such as Smith (1998, pp. 407–408, p. 459) and contemporary economists such as North (1990, pp. 64–65). The fact that the rule of law is essential for a nation’s economic performance, inter alia, by securing property rights and enforcing contracts, is also used as a theoretical presumption by the extensive empirical economic literature focusing on the relationship between the rule of law and economic performance (Acemoglu et al., 2001, p. 1369; Barro, 2001, p. 13; Brunetti et al., 1998, p. 353; Hall & Jones, 1999, p. 84; Knack & Keefer, 1995, p. 207; c.f. Li & Li, 2013; for a general review, see Asoni, 2008).

In this respect, some authors even start their analysis of the relationship between the rule of law and economic growth with the remark that “few would dispute that the security of property and contractual rights (…) are significant determinants of the speed with which countries grow” (Knack & Keefer, 1995, p. 207). However, although there is a clear understanding in the economic literature that the rule of law, among others, by securing property rights and enforcing contracts, is important for the economic performance of a nation, it seems worthwhile to once more identify the theoretical transmission channels between the rule of law and a country’s labor productivity growth by businesses. This is particularly the case considering the fact that, within an EU context, it is necessary to differentiate business investments in intangible capital from those in tangible capital. Following the argumentation of the existing economic growth literature (Benhabib & Spiegel, 1994 on modelling political instability; Knack & Keefer, 1995 on modelling the rule of law), one is able to identify two transmission channels of how the rule of law might influence a country’s labor productivity growth by businesses. First, the rule of law might directly be related to labor productivity growth by stimulating TFP growth. Second, the rule of law might stimulate business investments in intangible and tangible capital.

2.1 Direct Influence of the Rule of Law on Labor Productivity Growth by Businesses

The direct influence of the rule of law on labor productivity growth by businesses is exerted through its influence on an economy’s TFP growth (or technological progress) by businesses. TFP accounts for all components, which facilitate the overall production process and thus imply an amelioration of the general efficiency and effectiveness with which the business sector utilizes its given level of intangible and tangible capital. In this respect, an important channel through which the rule of law might positively impact the business sector’s TFP growth is via the reduction of transaction costs as proposed within the theoretical framework by North (1990, pp. 27–28 and pp. 64–65). Applying this theoretical framework, one can argue that a lower level of the rule of law will lead to higher transaction costs, hampering those activities that aim at raising productivity, for example, the invention and innovation of new technologies, resulting in a lower level of technological progress within a country’s business sector (North, 1990, pp. 64–65). This theoretical reasoning is prominently picked up by Hall and Jones (1999) in their elaboration of the rule of law as one central indicator within their concept of the term “social infrastructure”. Hall and Jones (1999) argue that the rule of law, by protecting the output of individual productive units and preventing predator behavior, is beneficial for high levels of output per worker by encouraging technological progress (Hall & Jones, 1999, pp. 95–97). The above argumentation is universal in nature and can be applied in the context of developing as well as highly developed economies, such as the EU member states.

2.2 Indirect Influence of the Rule of Law on Labor Productivity Growth by Businesses

In the absence of a substantial level of the rule of law, one would expect that entrepreneurs and businesses will in general invest less in intangible and tangible capital as the economic environment is strongly prone to uncertainty (Brunetti et al., 1998). Thus, a large part of the economic literature agrees on the fact that the rule of law should positively influence economic performance via the indirect channel by stimulating business investments in capital (c.f. Li & Li, 2013 who discuss the Chinese case). In this context, the literature argues that it would be expected that a business environment characterized by unclear property rights and uncertain contract enforcement would be associated with lower investment by companies (Brunetti et al., 1998, p. 353). Along these lines, it is argued that without secure property and contractual rights, investment would be discouraged (Knack & Keefer, 1995, p. 207), which will lead to lower levels of investments in capital (Hall & Jones, 1999, p. 95; North, 1990, p. 65).

However, before concluding that the rule of law would always be positively related to business investments, in particular when analyzing a country sample of advanced economies, such as the one from the EU, it seems necessary, for an adequate discussion, to distinguish between investments in tangible and intangible capital, given that the EU economies are on the verge of transforming themselves into knowledge economies (Piekkola 2011). Whereas protecting the property rights of tangible capital, such as nonresidential investments and machinery and equipment, has long been internalized within the institutional framework of many highly developed EU economies—with the rule of law’s roots being traceable inter alia to the Roman Empire (Finley, 1976)—protectiing the property rights of intangible capital, such as investments in enhancing the knowledge base of businesses including computerized information, innovative property, and economic competencies (Corrado et al., 2005) leading to patents, trademarks, copyrights, and design rights, is a more recent phenomenon tht prominently emerge in the 19 century (Mayer-Schönberger, 2010, p. 164).

In this respect, when considering advanced economies, such as those of the EU member states, one can take for granted that investments in tangible capital are well protected from theft and expropriation, even in countries with relatively lower levels of the rule of law. Conversely, in those economies exhibiting a relatively higher level of the rule of law it might even be that the rule of law, in its role as a regulator (Mayer-Schönberger, 2010, pp. 155–160), hampers investments in tangible capital. In this respect, a higher level of the rule of law might be associated with a higher level of, e.g., labor market regulations. By making the factor input of labor more costly, however, these labor market regulations might act as an incentive to invest in an environment that is less prone to regulation and in which the utilization of the labor factor is less costly (Nicoletti & Scarpetta, 2003). Thus, it would be plausible, for example, that within the transition countries of the EU a lower level of the rule of law would be associated with higher business investments in tangible capital. It might also potentially be that lower levels of the rule of law are associated with higher levels of corruption which ultimately act as a grease in fostering investment in tangible capital and growth (for a discussion of the literature asserting a positive relationship between corruption and growth, see Méon & Sekkat, 2005, p. 70).

Similar to the ambivalent relationship between the rule of law and tangible capital investments, one is able to identify both sets of arguments for the relationship between the rule of law and business investments in intangible capital. On the one hand, the rule of law’s function as a protector and enforcer of intellectual property rights will most likely be a key prerequisite for enhancing investment in intangible capital, and thus the knowledge base of businesses, aimed at generating patents, trademarks, copyrights, and design rights (Gould & Gruben, 1996, p. 323; pp. 326–327; for specific R&D activity see Park & Ginarte, 1997, p. 60). The fact that adequate protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights might be indeed a basic prerequisite for business investments in intangible capital in the EU context is related to the fact that the given institutional structure has not yet fully adapted to the new reality of a knowledge economy, thus making intangible capital investments more prone to theft and property rights violation. Thus, in particular, in an EU context, it can be argued that the rule of law, by securing intellectual property rights, functions as a core incentive for entrepreneurial activity and business investments in intangible capital (Baumol, 2002, p. 8; Mayer-Schönberger, 2010, pp. 164–65). However, similar to the arguments presented in the discussion above on investment in tangible capital investments, it should also be mentioned that an excessively strict intellectual property regime might hamper innovation activity, as it might be primarily used by large corporations to block new market entrants (Dosi et al., 2006; Mayer-Schönberger, 2010, p. 166; Verspagen, 2006).

To conclude, in the context of the EU, the theory on the impact of the rule of law on both types of business capital investments, tangible and intangible capital, remains ambiguous and needs to be tested empirically.

3 Model Specifications, Research Design, Operationalization, and Data

3.1 Model Specifications

As mentioned above, the literature on economic growth (see notably Benhabib & Spiegel, 1994, on modelling political instability and Knack & Keefer, 1995, on modelling the rule of law) has identified two distinct channels of how the rule of law might affect labor productivity growth: 1) a direct channel by stimulating TFP growth and 2) an indirect channel by stimulating business investments in intangible and tangible capital.

3.1.1 A Model for the Direct Contribution of the Rule of Law to Labor Productivity Growth

Following the theoretical framework by Roth and Thum (2013, pp. 494–95), who combine a model specification by Corrado et al. (2009) with one from Benhabib and Spiegel (1994), the starting point for estimating the direct contribution of the rule of law on labor productivity growth by businesses is the following intangible capital-augmented Cobb-Douglas production function,

where Qi,t is GVA (Gross Value Added for the non-farm business sectors c-k + o excluding real estate activities) expanded by the investment flows of business intangible capital in country i and period t, R is the intangible capital stock by businesses, K is the tangible capital stock by businesses, L is labor, and A is TFP. Following the authors and assuming constant returns to scale, rewriting the Cobb-Douglas production function in intensive form and taking differences in natural logarithms, the following equation is obtained:

where ui,t = ln εi,t − ln εi,t − 1, (lnqi,t − ln qi,t−1) is labor productivity growth (GVA for the non-farm business sectors c-k + o excluding real estate activities expanded by the investment flows of business intangible capital in country i and period t, (lnki,t − ln ki,t−1) and (lnri,t − ln ri,t−1) represents the growth of tangible and intangible capital services and (lnAi,t − ln Ai,t−1) represents the TFP growth.Footnote 1

As elaborated above, we believe that the rule of law should positively affect labor productivity growth by businesses via its TFP term. Utilizing an extended approach of Roth and Thum (2013, 495), a model for (lnAi,t − ln Ai,t−1) is specified as follows:

where c is the constant term and represents exogenous technological progress, RoLi,t is the level of the rule of law of a country, Hi,t is the level of human capital and reflects the capacity of a country to innovate domestically, the term \( {H}_{i,t}\frac{\left({Q}_{\max, t}-{Q}_{i,t}\right)}{Q_{i,t}} \) proxies a catch-up process, the term (1 − uri,t) takes into account the business cycle effect (and is measured as 1–unemployment rate),Footnote 2 the term \( \sum \limits_{j=1}^k{X}_{j,i,t} \) is a sum of k extra policy variables that could possibly explain TFP growth and cdi,t = 2001 is a crisis dummy to control for the economic downturn in 2001 after the bursting of the Information Technology bubble in the year 2000 and the 9/11 attack in the United States in 2001. Inserting Eq. (3.3) into Eq. (3.2) provides the baseline model to be estimated within the econometric estimation in Sect. 5:

We now turn our attention to displaying the model specification of the indirect contribution of the rule of law to labor productivity growth.

3.1.2 The Indirect Contribution of the Rule of Law to Labor Productivity Growth

Applying the logic of the model specifications by Knack and Keefer (1995, pp. 220–23) and Benhabib and Spiegel (1994, pp. 163–66) to the model specification of Eq. (3.4), the indirect impact of the rule of law on labor productivity via the two investment channels, business investment in intangible and tangible capital can be expressed as follows:

where Ni,t, Ii,t represent the real investment rates for intangible and tangible capital by businesses respectively, c displays the constant term, RoLi,t is the level of the rule of law in country i and period t, Ri,t, and Ki,t are the intangible and tangible capital stock by businesses, respectively, Hi,t is the level of human capital, the term (1 − uri,t) takes into account the business cycle effect, the term \( \sum \limits_{j=1}^k{X}_{j,i,t} \) is a sum of k extra policy variables which could possibly explain investment rates in tangible and intangible capital, cdi,t = 2001 is a crisis dummy to control for the economic downturn in 2001 following the bust of the Information Technology bubble in 2000 and the 9/11 attack in 2001 and εi,t is the error term.

3.2 Research Design

Whereas the description of the distribution of the rule of law indicator of the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators Project (WGIP) (Kaufmann et al., 2010) was conducted within an EU-27 country sample, the econometric analysis between the rule of law and labor productivity growth as well as between the rule of law and investments in intangible and tangible capital will be limited to an EU-13 country sample. Similar to the analysis of Roth and Thum (2013, pp. 495–96), this is due to limitations in the EUKLEMS data (O’Mahony & Timmer, 2009) concerning tangible capital data. The econometric exercise is thus limited to the following 13 EU countries: Austria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Due to data availability concerning intangible stocks and the construction of intangible capital services, the time period of the analysis is restricted to 1998 to 2005. Following an approach by Bassanini and Scarpetta (2001) and utilizing yearly data, an overall amount of 98 observations were retrieved.Footnote 3 Given that the two transition countries—the Czech Republic and Slovenia—are following a different pattern than the 11 EU-15 countries (see Fig. 3.4), a full country sample with all 13 EU countries will be compared to a sample of 11 EU-15 countries, excluding the two transition countries. The whole research design applies to non-farm business sectors c-k + o.

3.3 Operationalization and Measurement of the Data

Although data from the World Justice Project (WJP) (Agrast et al., 2013) would have been based on an excellent operationalization of the rule of law (Agrast et al., 2013, p. 11) and would have offered high-quality data by utilizing output measures, as well as individually constructed and polled data (Agrast et al., 2013, pp. 185–90) (for a detailed discussion, see Appendix 1), the data are incompatible with this contribution’s research design as the WJP only started to conduct its first wave of polling in 2009. Similarly, data from the European Commission (CEPEJ, 2012; European Commission, 2013a), offering a multitude of interesting input indicators concerning the rule of law, are incompatible with the present study’s research design, as these indicators are only measured from 2004 onward. Moreover, in contrast to data from WGIP and WJP, the European Commission has not yet constructed an overall rule of law index, by combining the most relevant indicators to form an overall index. Given the fact that the WGIP offers time series data from 1996 to 2012Footnote 4 and thus covers the time from 1998 to 2005, data from the WGIP are utilized in the descriptive and econometric sections of this contribution. In addition, although the WGI’s operationalization of the rule of law is less conceptualized than the one from the WJP (for a detailed elaboration, see again Appendix 1), it offers a wider set of information by aggregating indicators concerning the rule of law from 23 different data sources, including a total of 84 indicators.Footnote 5 All single indicators are then aggregated to construct the rule of law indicator by using an unobserved components model (Kaufmann et al., 2010, p. 9). The unit of the rule of law indicators applied to the 214 countries are those of a standard normal random variable and range from −2.5 to 2.5 (Kaufmann et al., 2010, p. 9 and p. 15).

Beyond the rule of law indicators, the other data for the following econometric analysis were taken from the various sources described below. Data on the real investments rates and stock data of intangible capital were taken from the INNODRIVE macro dataset (INNODRIVE, 2011). In accordance with the INNODRIVE data, intangible capital investment included investment in: 1) software, 2) R&D, 3) new architectural and engineering designs, 4) new product development in the financial services industry, 5) mineral exploration and copyright and licenses costs, 6) organizational capital (own account component), 7) organizational capital (purchased component), 8) firm-specific human capital, 9) advertising, and 10) market research. The construction of intangible capital stocks and intangible capital services follows the approach by Roth and Thum (2013, p. 497). Data on GVA (nonfarm business sectors excluding real estate activities), tangible capital stocks, capital compensation, gross fixed tangible capital investments, tangible investment price indices and labor input (number of hours worked), and depreciation rates were taken from the EUKLEMS database (O’Mahony & Timmer, 2009). Tangible capital included: 1) communications equipment, 2) computing equipment, 3) total nonresidential investment, 4) other machinery and equipment, 5) transport equipment, and 6) other assets, but excluded residential capital. Similar to intangible capital services, tangible capital services were constructed following the approach by Roth and Thum (2013, p. 497). Human capital is measured as the percentage of the population who attained at least upper secondary education, which is taken as a proxy for the inherent stock of human capital. These data are provided by Eurostat. The unemployment rate is taken from Eurostat and is utilized to calculate the business-cycle effect.

4 Empirical Description of the Rule of Law within the EU

To analyze the cross-sectional variance of the rule of law in the European context, Fig. 3.1 displays the distribution of the average value of the rule of law in an EU-27 country sample over the time period 1998–2005. The lower and upper bound values, indicated by the symbols ● and ▲, respectively, report the 90% confidence interval associated with the rule of law estimate to identify potential measurement errors (Kaufmann et al., 2010, p. 13).

The rule of law in the EU-27, 1998–2005

Notes: The data are based upon the WGIP (Kaufmann et al., 2010) and are averaged from 1998 to 2005. The 13 countries included in the econometric analysis are denoted with an asterisk.

Figure 3.1 clarifies three important issues. First, across the EU-27, there exists a significant variance concerning the rule of law. Whereas Finland leads the ranking with an average value of 1.95, Bulgaria and Romania, which are positioned at the end of the ranking, only display average values of −0.20 and −0.19. The fact that there is sufficient variation even in an EU-27 country sample is also highlighted by a sizeable standard deviation of 0.61 by a given mean of 1.09 (see variable named “Rule of law - EU27 - average 98-05” in Table 3.A1 in Appendix A3).

Second, the given variance in the rule of law is driven by certain country regime typologies.Footnote 6 Whereas countries from the coordinated, liberal, and Scandinavian regime typology are solely located at the upper third of the distribution, eight of the nine countries in the lower third of the distribution are from transition and Baltic countries.

Third, Italy, the fourth-largest EU economy, is the only EU-15 country that is positioned in the lower third of the distribution, with a value of 0.66. Even if considering Italy’s upper bound value of 0.95, it still ranks behind the lower bound values of France (1.07), Germany (1.33), and the UK (1.36). Thus, Italy’s level of the rule of law is significantly smaller in comparison to the three other equally large EU economies.Footnote 7

The fact that the variance in the rule of law indicator within the EU is driven by regime characteristics is more clearly highlighted in Fig. 3.2, which compares six regime typologies within the EU-27. Whereas the Scandinavian (Finland, Denmark, and Sweden), Coordinated (Austria, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Belgium), and Liberal (the United Kingdom and Ireland) regime typologies are all positioned at values of 1.5 and above, the Mediterranean (Italy, Spain, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, and Malta) typology is positioned only at a value of around 1.0. The transition (Bulgaria, Romania, Slovak Republic, Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, and Slovenia) and Baltic (Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia) regime typologies display significantly lower levels of the rule of law than the other four.

Regime typologies and rule of law in the EU-27, 1998–2005

Notes: Data are based on the World Governance Indicators by Kaufmann et al. (2010). Data are averaged data from 1998 to 2005. The Baltic regime typology, which is marked with an asterisk, is the only typology not present within the econometric analysis.

Having already shown that there is a substantial degree of variance between the countries of the EU-27 and its various regime typologies, Fig. 3.3 explores whether there is also sufficient variance in the time trends within the EU-27. Figure 3.3 clarifies that, in contrast to the significant between-variance, the within-variance is less pronounced in the time period 1998 to 2005 (identified in Fig. 3.3 with the two dashed lines). In most countries, time trends behave in a very stable fashion. In fact, within the time period 1998 to 2005, there is no significant increase or decline to be observed when analyzing a 90% confidence interval. However, the conclusion that the rule of law indicator is a constant variable without any within-variance would also be premature. In analyzing changes over time from 1996 to 2012 (as in addition displayed in Fig. 3.3 outside the dashed lines) particularly in Estonia and Latvia, one finds significant increases when using the 90% confidence interval (see here also Kaufmann et al., 2010, p. 28). Relaxing the 90% confidence interval as suggested by Kaufmann et al. (2010, p. 14), over the same time period, one would, e.g., also detect a significant decrease in the level of the rule of law in Italy.Footnote 8,Footnote 9

Trends of the rule of law in the EU-27, 1998–2005

Notes: Time trends display the period from 1996 to 2012. The two dashed lines represent the time period for the econometric analysis from 1998 to 2005. The * next to the country name denotes those countries that are included in the econometric analysis.

Overall, given the stable within-variation in most countries (utilizing the 90% confidence interval) and the significant between-variation, a positive relationship between the rule of law and labor productivity growth and intangible and tangible capital investment rates would foremost be based on the cross-sectoral or between-variance.

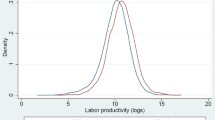

Before shifting our attention to the econometric analysis, Fig. 3.4 depicts respectively the bivariate relationship between the rule of law and business investment in intangible and tangible capital for the 13 EU economies, as covered within the following econometric exercise. Whereas one detects a positive bivariate relationship between the rule of law and business investment in intangible capital, interestingly the opposite is true for the relationship between the rule of law and business investments in tangible capital. Figure 3.4 clarifies, however, that this negative relationship between the rule of law and tangible capital investment is strongly driven by the two transition countries Czech Republic and Slovenia. The same does not hold for the relationship between the rule of law and intangible capital investment. Once the transition countries are excluded, the positive relationship between the rule of law and intangible capital investment remains robust (see here also Fig. 3.A1 in Appendix A3, which depicts the relationship for an EU-25 country sample).

Scatter plot of the relationship between the rule of law and business investments in intangible and tangible capital in the EU-13, 1998–2005

Notes: Data on intangible capital investments are taken from the INNODRIVE dataset (INNODRIVE, 2011). Data on tangible capital investment are taken from the EUKLEMS dataset (O’Mahony & Timmer, 2009). The rule of law indicator is taken from the WGIP. The long dashed line represents the linear regression line for a sample considering all countries. The short dashed line represents the linear regression line for a scenario excluding the two transition countries the Czech Republic and Slovenia.

5 Econometric Results

5.1 Econometric Results between the Rule of Law and Labor Productivity Growth

When estimating Eq. (3.4), the standard methods for panel estimations are fixed or random. The fixed effects are calculated from differences within each country across time; the random-effects estimation, in contrast, incorporates information across individual countries as well as across periods of time. The major drawback with random-effects estimations, despite their being more efficient, is that they are consistent only if the country-specific effects are uncorrelated with the other explanatory variables (Forbes, 2000, c.f. Mundlak, 1978). A Hausman specification test can evaluate whether this independent assumption is satisfied (Hausman, 1978). The Hausman test applied here indicates that a random-effects model can be utilized.Footnote 10 In addition, to control for potential cross-sectional heteroskedasticity, a robust VCE estimator was used.Footnote 11 As highlighted within the research design of this study, the random-effects estimation uses 13 countries with 98 observations. It is an almost balanced panel, with two countries (the Czech Republic and Slovenia) missing three time observations from 1998 to 2000. Regression 1 in Table 3.1 shows the estimation results when estimating Eq. (3.4) (Table 3.1).

In accordance with economic theory, with a coefficient of 1.3, the rule of law indicator is positively related to labor productivity growth. However, the effect is weak (significant only at the 90% confidence level). Controlling for endogeneity,Footnote 12 by utilizing the lagged value of the rule of law indicator in regression 2, renders a slightly higher coefficient (1.6) and increases the significance of the relationship (95% level). Whereas utilizing a lagged value of the potential endogenous variable is a common approach in the economic literature (see e.g. Clemens et al., 2012, p. 591), utilizing an instrumental approach is argued to be preferable (Reed, 2013). However, as the author was not able to retrieve a valid external instrument in the EU contextFootnote 13 and as the utilization of internally generated instruments by using the lags of the endogenous variables (Griliches & Hausman, 1986) would lead to weak instruments (Mc Kinnish, 2000) and respectively strongly biased estimates (Murray, 2006; Stock & Watson, 2007), the above-mentioned lagged value approach was chosen.Footnote 14 In this respect, one should highlight that in general within the social sciences causal inference should be foremost theoretically driven and generally cannot be demonstrated directly from the data (Frees, 2004, 205). Applying this study’s research design and excluding the two transition countries Czech Republic and Slovenia in regression 3, the coefficient increases (1.8) and the relationship is rendered more significant.

How should one interpret the coefficient of 1.8, as displayed in regression 3? The rule of law indicator for the given 98 observations in the sample ranges from 0.47 in Italy in the year 2005 to 1.97 in Finland in the year 2004 (for the summary statistics, see also the variable named “Rule of Law – EU13” in Table 3.A1 in Appendix A3). Given the fact that most of the variance of the rule of law indicator is cross-sectional (see here Figs. 3.1 and 3.3), it seems reasonable to interpret the coefficients as follows: If Italy, with an average value of 0.66 (as displayed in Fig. 3.1) would hypothetically be able to reach the same level of the rule of law as Finland, with an average value of 1.95 (as displayed in Fig. 3.1). this increase would be associated with an increase of its labor productivity growth by approximately 2.3%.Footnote 15 However, as the overall effect of all TFP components within the utilized model specification and research design only accounts for 10% of the share of labor productivity (Roth & Thum, 2013, p. 503), the analysis will now continue to explore the indirect channels.

5.2 Determinants of Intangible and Tangible Business Capital Investment

Regression 1 in Table 3.2 shows the results when estimating Eq. (3.5) with the help of a random-effects estimation controlling for potential cross-sectional heteroscedasticity.Footnote 16 When estimating the association between the rule of law and investment in business intangible capital, one detects a positive (1.1) but weak association (significant at the 90% confidence level). Applying a similar methodological logic as discussed above and controlling for endogeneity,Footnote 17 regressions 2–4 incorporate the first, second, and third lag of the value of the rule of law. Whereas the first lag renders an insignificant association, the incorporation of both the second and third lag yields similar coefficients (1.4 and 1.0) and more significant associations between the rule of law and business investment in intangible capital (significant at the 95% confidence level). If one excludes the two transition countries Czech Republic and Slovenia (for their location within the bivariate relationship (see also Fig. 3.4), the coefficient remains robust (1.2) and significant at the 95% confidence level). Similar to the above interpretation, the coefficient of 1.2% could be interpreted in the following manner: if Italy would be able to gain the same average level of the rule of law as Finland, this increase would be associated with an increase in intangible capital investment of approximately 1.5%.Footnote 18

Regressions 6–10 estimate Eq. (3.6), the association between the rule of law and tangible capital investment by businesses, and apply the same methodological procedure as in regressions 1–5. In alignment with the bivariate relationship (Fig. 3.4), regressions 6–9 yield a negative coefficient of −5.7 to −7.3. Utilizing the third lag of the rule of law in regression 9 yields the most significant result (significant at the 99% confidence level). However, again in alignment with the bivariate relationship in Fig. 3.4, once the two transition countries Czech Republic and Slovenia are excluded in regression 10, the relationship between the rule of law and investments in tangible capital loses significance (and explanatory power with a R-square between value as low as 0.02).

Thus, the significant negative relationship between the rule of law and investment in business tangible capital is entirely driven by the two transition countries. In those two countries, a relatively low level of the rule of law is associated with a high investment rate in tangible capital. As theoretically discussed, this might be because a lower level of the rule of law is associated with less regulatory activity, thus making it more attractive for enterprises to make tangible capital investments.

6 Empirical Conclusion, Discussion, and Policy Conclusion

6.1 Empirical Conclusion

This contribution has investigated the relationship between the rule of law and labor productivity growth in an EU context. Seven findings emerge from the empirical analysis.

First, there exists considerable variance concerning the rule of law within an EU-27 country sample. The Baltic, transition, and Mediterranean countries incorporate significantly lower levels of rule of law than the liberal, coordinated, and Scandinavian countries. Countries such as Romania, Bulgaria, Italy, and Greece have significantly lower positions than the three largest economies in the EU, namely France, Germany, and the UK.

Second, although one detects a significant variance in some EU countries over time, e.g. an increase in Latvia and Estonia, the main variance is cross-sectional in nature. In countries such as Germany, Austria, and Finland, time trends behave in a very stable fashion.

Third, using a random-effects estimation among an EU-13 country sample with 98 overall observations in an intangible capital-augmented production model and controlling for endogeneity by using the first lag, the rule of law is significantly and positively related to labor productivity growth by stimulating its TFP growth.

Fourth, in analyzing the relationship between the rule of law and business intangible capital investment graphically within a bivariate relationship for an EU-25 country sample and econometrically by using a random-effects estimation across an EU-13 country sample with 98 observations and controlling for endogeneity by using the second and third lag, one detects a positive association between the level of the rule of law and business investment of intangible capital.

Fifth, in contrast to the positive and significant association between the rule of law and business investments in intangible capital, business investments in tangible capital are negatively related to the level of the rule of law. This negative finding is entirely driven by the two transition countries in which a low level of the rule of law is associated with a high level of investment in tangible capital by businesses.

Sixth, overall, the results indicate that an improvement in the rule of law in those countries with relatively low levels would be beneficial in facilitating the transformation towards becoming knowledge economies. It seems that the rule of law, by protecting and enforcing the intellectual property rights associated with patents, copyrights, and trademarks, stimulates investments in intangible capital.

Seventh, it should be highlighted that more empirical research is needed to corroborate these first findings. It would be of particular interest in corroborating the findings by utilizing an external instrumental variable to address potential endogeneity issues.

6.2 Discussion of the Results Considering the Underlying Theoretical Literature

The empirical findings in the EU context over the period 1998–2005 confirm the theoretical arguments that the rule of law, by lowering transaction costs, positively contributes to economic performance (North, 1990; Hall & Jones, 1999).

Concerning the ambivalent theoretical reasoning on the relationship between both the rule of law and investments in intangible and tangible capital by businesses, the empirical findings support the theoretical argument that in the EU from 1998 to 2005, the rule of law, by securing intellectual property rights, was beneficial to business investments in intangible capital (Baumol, 2002, p. 8; Mayer-Schönberger, 2010, pp. 164–65). The empirical findings seem to reject concerns about an excessively strict intellectual property regime hampering innovation activity (Dosi et al., 2006; Mayer-Schönberger, 2010, p. 166; Verspagen, 2006). However, the rule of law is either negatively (once accounting for the transition countries) or insignificantly related to investment in tangible capital. In the EU context from 1998 to 2005, the findings indicate that the rule of law in its role as regulator either hampers business investment in tangible capital (Mayer-Schönberger, 2010, pp. 155–160; Nicoletti & Scarpetta, 2003) or that the variance in the rule of law does not matter for investment in tangible capital.

Overall, these first empirical findings of this study tend to support the validity of the European Commission’s claim that the rule of law is important for the economic performance of EU economies (European Commission, 2013a, p. 1).

6.3 Policy Conclusions

Six policy conclusions can be drawn from the foregoing analysis.

First, in order to enhance labor productivity growth—in line with the Europe 2020 strategy (European Commission, 2010)—it would be beneficial to enhance the level of the rule of law in those countries that perform relatively worse in an EU context. In EU-15 countries such as Italy and Greece, and transition countries such as Romania and Bulgaria, low levels of the rule of law hamper labor productivity growth. In those countries, enhancing the level of the rule of law by reforming the judiciary system seems to be essential. In this regard, it is favorable that the European Commission is well aware of the necessity to improve the rule of law in those countries. Among other ways, this awareness is made explicit by its country recommendations within the European semester. In the Italian case, the European Commission recommends to “simplify the administrative and regulatory framework for citizens and businesses and reduce the duration of case-handling and the high levels of litigation in civil justice, including by fostering out-of-court settlement procedures (…) and strengthening the legal framework for the repression of corruption” (European Commission, 2013b, p. 7). In the case of Romania, the European Commission recommends: “to strengthen the governance and the quality of institutions and the public administration (…) and step up efforts to improve the quality, independence and efficiency of the judicial system in resolving cases and fight corruption more effectively” (European Commission, 2013c, p. 7).

Second, the low level of the rule of law in the third-largest economy in the eurozone, Italy, needs to be taken into consideration in particular in efforts to improve the governance of the euro area. The significant difference in the rule of law in those three countries, with Italy performing significantly worse compared to France and Germany, leads, inter alia, to a continued divergence in labor productivity growth and time-lagged investments to business intangible capital. Thus, in the long run, in order to smooth economic divergences between the three largest euro area economies, Italy’s level of the rule of law would need to be increased.

Third, DG Justice should continue its effort to construct a scoreboard on the rule of law. Similar to the methodological approaches taken by the WJP and WGIP, this scoreboard should aim at building an index based on the rich data as presented by the CEPEJ (2012) from 2004 onward. The operationalization of this index could be based on the methodological approach of the WJP In contrast to the WJP, however, the index could consist of a mix of the rule of law as measured de facto and as measured based upon expenditure-based data. In this regard, it would be important that the European Commission would be willing to contribute sufficient resources to allow for constructing time series data over the coming years, which would allow researchers to compare potential changes in a rule of law index over time.

Fourth, in the medium to long run, such an index as constructed by DG Justice, which takes into consideration the specific aspects of the EU economies, should be incorporated as a benchmark indicator within the European semester. In particular, an improvement in the various underlying indicators of the rule of law in some Mediterranean and transition economies should be closely monitored by the European semester. Most importantly, however, the progress of the third-largest euro area economy and the fourth-largest EU economy, namely Italy, should be closely monitored.

Five, DG Justice should finance research exploring the effects of the most recent economic crisis in the euro-area periphery, particularly in Spain and Greece, on the levels of the rule of law. First evidence from the WJP indicates that the rule of law in Spain has dropped in four out of the eight dimensions measured (World Justice Project, 2014, p. 37). In light of the systemic trust crisis in Spain triggered by the economic crisis (Roth et al., 2013), the development of a decrease in the rule of law in the fourth-largest eurozone economy, i.e., Spain, ought to be closely monitored.

Six, following the initial theoretical arguments advanced by the World Bank (2006, p. 98), future research endeavors should evaluate how much of the expenditure in the national judicial systems should be considered investment in intangible capital. As these investments are most often undertaken by the public sector and not by the business sector, they should be coined public investment in intangible capital. In this regard, it can easily be concluded that a share of the public expenditure in the judicial system represents an investment by its very nature, as the existence of an efficient judicial system is a prerequisite for the protection and enforcement of property and contract rights, which are essential for the conduct of economic activities within functioning market economies. Future research endeavors should thus try to estimate how much of the expenditure should be considered investment in order to be able to adequately revise the national accounting systems.

Notes

- 1.

For the detailed formula of the calculation of the tangible and intangible capital services growth, see Roth and Thum (2013).

- 2.

This approach was introduced by Guellec and van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie (2001, pp. 107–116).

- 3.

Due to shorter time series in intangible capital investment in the Czech Republic and Slovenia, we were able to generate only five time observations for intangible capital services for these two transition countries but eight for the other 11 countries.

- 4.

The data from 1996 to 2002 have only been collected on a 2-year basis in 1996, 1998, 2000, and 2002. Thus, for the econometric analysis at hand, the values for 1995, 1997, 1999, and 2001 have been interpolated by linear interpolation. The data can be downloaded from http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home.

- 5.

A list of all 23 data sources and 84 indicators can be downloaded online from the World Bank’s website (http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#doc).

- 6.

For an introduction to the different regime typologies, see among others Hall and Soskice (2001).

- 7.

This significant difference between Italy and the other large EU economies is also shown in the analysis of four important subindicators of the rule of law, as presented in Fig. 3.A2 in Appendix A3: 1) enforcement of patents and copyrights, 2) property rights, 3) stable laws, and 4) effective enforcement of civil justice. Italy’s scores are significantly lower than those of the UK, France, and Germany in all four indicators.

- 8.

It should be noted that the indicators utilized were increased from 7 in 1996 to 13 in 2012. However, those indicators which were utilized over the 17-year time period decreased steadily. The country report for Italy can be downloaded at http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#countryReports.

- 9.

The assumption that the rule of law is not a constant variable is also confirmed by analyzing time series data from the WJP for the case of Spain. From 2012 to 2013, in times of economic crisis, the WJP data identify a decline in Spain in four out of eight rule of law indicators (World Justice Project, 2014, p. 37).

- 10.

The test statistic is χ2(7) = 2.70. This clearly fails to reject the null hypothesis of no systematic differences in the coefficients.

- 11.

Using an xtoverid command (Schaffer & Stillman, 2010), the Sargan-Hansen test statistic is χ2(7) = 5.4. This clearly fails to reject the null hypothesis of no systematic differences in the coefficients.

- 12.

When running growth regressions, such as in Eq. (3.4), one must be aware of the possibility that the left-hand side and the right-hand side variables will affect each other. More specifically, the rule of law might be endogenous, affected by a common event such as an economic shock, or stand in a bidirectional relationship with labor productivity. Thus, an increase in labor productivity growth might, for example, increase spending in the judicial system and increase the level of the rule of law.

- 13.

For a discussion of a valid instrument for the rule of law within the field of development economics, see Appendix A2.

- 14.

In addition, the utilization of internally generated instruments by using the lagged values only holds if the error term would be serially uncorrelated (Griliches and Hausmann 1986, p. 94). A test for serial correlation of the error term as introduced by Drukker (2003) indicates that this assumption was violated. Detailed results can be obtained from the author if it were able on request.

- 15.

The calculation is as follows: Given that the distance from the average value of Italy to the average value of Finland is 1.29 (1.95–0.66), labor productivity growth gains for Italy would be approximately 2.3% (1.29*1.8) if it managed to close the gap with Finland.

- 16.

Using an xtoverid command (Schaffer & Stillman, 2010), the Sargan-Hansen test statistic is χ2(5) = 4.8. This clearly fails to reject the null hypothesis of no systematic difference in the coefficients. Thus, the test applied here indicates that a random-effects model with a robust VCE estimator can be used.

- 17.

When running growth regressions, such as in Eqs. (5) and (6), one must be aware of the possibility that the left-hand side and the right-hand side variables will affect each other. More specifically, the rule of law might be endogenous, affected by a common event such as an economic shock, or stand in a bidirectional relationship with investments in tangible and intangible capital. Thus, an increase in the investment in intangible and tangible capital might, for example, be related to an increase in spending in the judicial system and ultimately lead to a higher rule of law.

- 18.

The calculation is as follows: Given that the distance from the average value of Italy to the average value of Finland is 1.29 (1.95–0.66), investments in intangible capital by businesses would be approximately 1.5% (1.29*1.2) higher if it managed to close the gap with Finland.

- 19.

Cyprus, Malta, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, and Ireland are not included due to missing data in the WJP data.

- 20.

The 23 sources are: African Development Bank Country Policy and Institutional Assessments, Afrobarometer Survey, Asian Development Bank Country Policy and Institutional Assessments, Business Enterprise Environment Survey, Bertelsmann Transformation Index, Freedom House Countries at the Crossroads, Economist Intelligence Unit Riskwire and Democracy Index, Freedom House, World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report, Global Integrity Index, Gallup World Poll, Heritage Foundation Index of Economic Freedom, Cingranelli-Richards’ Human Rights Database and Political Terror Scale, IFAD Rural Sector Performance Assessments, Institutional Profiles Database, Latinobarometro, World Bank Country Policy and Institutional Assessments, Political Risk Services International Country Risk Guide, US State Department Trafficking in People report, Vanderbilt University Americas Barometer, Institute for Management and Development World Competitiveness Yearbook, World Justice Project Rule of Law Index, and Global Insight Business Conditions and Risk Indicators. The list can be downloaded at http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#doc.

- 21.

A list of all 23 data sources and 84 indicators can be downloaded online on the World Bank website (http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#doc).

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American Economic Review, 91, 1369–1401.

Agrast, M., Botero, J., Martinez, J., Ponce, A., & Pratt, C. (2013). WJP rule of law index 2012–2013. World Justice Project.

Asoni, A. (2008). Protection of property rights and growth as political equilibria. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22, 953–987.

Barro, R. J. (2001). Human capital and growth. American Economic Review, 91, 12–17.

Bassanini, A., & Scarpetta, S. (2001). The driving forces of economic growth: Panel evidence for the OECD countries. OECD Economic Studies, 33, 9–56.

Baumol, W. J. (2002). Entrepreneurship, innovation and growth: The David-goliath Symbiosis. Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance, 7, 1–10.

Benhabib, J., & Spiegel, M. M. (1994). The role of human capital in Economic Development– Evidence from aggregate cross-country data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 34, 143–173.

Botero, C. B., & Ponce, A. (2011). Measuring the rule of law, world justice project working paper series no. 001. World Justice Project.

Brunetti, A., Kisunko, G., & Weder, B. (1998). Credibility of rules and economic growth: Evidence from a worldwide survey of the private sector. World Bank Review, 12, 353–384.

CEPEJ (2012). Evaluation of European judicial systems, report of the European Commission for the efficiency of justice. Council of Europe. http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/cooperation/cepej/evaluation/default_en.asp

Clemens, M. A., Radelet, S., Bhavnani, R. R., & Bazzi, S. (2012). Counting chickens when they hatch: Timing and the effects of aid on growth. Economic Journal, 122, 590–617.

Corrado, C., Hulten, C., & Sichel, D. (2005). Measuring capital and technology: An expanded framework. In C. Corrado, J. Haltiwanger, & D. Sichel (Eds.), Measuring Capital in the new Economy (pp. 11–46). University of Chicago Press.

Corrado, C., Hulten, C., & Sichel, D. (2009). Intangible capital and U.S. Economic Growth. Review of Income and Wealth, 55, 661–685.

Dosi, G., Marengo, L., & Pasquali, C. (2006). How much should society fuel the greed of innovators? On the relations between appropriability, opportunities and rates of innovation. Research Policy, 35, 1110–1121.

Drukker, D. (2003). Testing for serial correlation in linear panel-data models. Stata Journal, 3, 168–177.

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (2003). Tropics, germs and crops: How endowments influence economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 50, 3–39.

Edquist, H. (2011). Can investment in intangibles explain the Swedish productivity boom in the 1990s?. Review of Income and Wealth, 57, 658–682.

European Commission. (2010). Europe 2020. A strategy for smart sustainable and inclusive growth. Communication from the European Commission.

European Commission. (2013a). The EU justice scoreboard - a tool to promote effective justice and growth, COM (2013) 160 final. European Commission.

European Commission. (2013b). Recommendation for a council recommendation on Italy’s 2013 national reform programme, COM (2013) 362 final. European Commission.

European Commission. (2013c). Recommendations for a council recommendation on Romania’s 2013 national reform programme, COM (2013) 373 final. European Commission.

Finley, M. (1976). Studies in Roman property. Cambridge University Press.

Forbes, K. (2000). A reassessment of the relationship between inequality and growth. American Economic Review, 90, 869–887.

Frees, E. W. (2004). Longitudinal and panel data: Analysis and applications in the social sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Fukao, K., Miyagawa, T., Mukai, K., Shinoda, Y., & Tonogi, K. (2009). Intangible Investment in Japan: Measurement and contribution to economic growth. Review of Income and Wealth, 55, 717–736.

Gould, D. M., & Gruben, W. C. (1996). The role of intellectual property rights in economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 48, 323–350.

Griliches, Z., & Hausman, J. A. (1986). Errors in variables in panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 31, 93–118.

Guellec, D., & van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie, B. (2001). R&D and productivity growth: Panel data analysis of 16 OECD countries. OECD Economic Studies, 33, 103–126.

Haggard, S., & Tiede, L. (2011). The rule of law and economic growth: Where are we? World Development, 39, 673–685.

Hall, R., & Jones, I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114, 83–116.

Hall, P. A., & Soskice, D. (Eds.). (2001). Varieties of capitalism: The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford University Press.

Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrics, 46, 1251–1271.

INNODRIVE. (2011). INNODRIVE intangibles database. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/214576/reporting/de.

Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2002). Growth without governance, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2928. World Bank.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2007). The worldwide governance indicators project: Answering the critics, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4149. World Bank.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology, data and analytical issues, World Bank policy research working paper no. 5430. World Bank.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1995). Institutions and economic performance: Cross country tests using alternative institutional measures. Economics and Politics, 7, 207–227.

Li, R. Y. M., & Li, Y. L. (2013). Is there a positive relationship between law and economic growth? A paradox in China. Asian Social Science, 9, 19–30.

Marrano, M. G., Haskel, J., & Wallis, G. (2009). What happened to the knowledge economy? ICT, intangible investment, and britain’s productivity record revisited. Review of Income and Wealth, 55, 686–716.

Mayer-Schönberger, V. (2010). The law as stimulus: The role of law in fostering innovative entrepreneurship. Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, 6, 153–188.

Mc Kinnish, T. G. (2000). Model sensitivity in panel data analysis: Some caveats about the interpretation of fixed effects and differences estimators, unpublished manuscript. University of Colorado.

Méon, P. G., & Sekkat, K. (2005). Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of growth? Public Choice, 122, 69–97.

Mundlak, Y. (1978). On the pooling of times series and cross-section data. Econometrica, 1, 69–85.

Murray, M. P. (2006). Avoiding invalid instruments and coping with weak instruments. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 120–126.

Nakamura, L. I. (2010). Intangible assets and National Income Accounting. Review of Income and Wealth, 56, S135–S155.

Nicoletti, G., & Scarpetta, S. (2003). Regulation, productivity and growth: OECD evidence. Economic Policy, 18, 9–72.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

O’Mahony, M., & Timmer, M. P. (2009). Output, input and productivity measures at the industry level: EU KLEMS database. Economic Journal, 199, F374–F403.

Park, W. G., & Ginarte, J. C. (1997). Intellectual property rights and economic growth. Contemporary Economic Policy, XV, 51–61.

Piekkola, H. (2011). Intangible Capital: the Key to Growth in Europe. Intereconomics, 46, 222–228.

Reed, W.R. (2013). On the practice of lagging variables to avoid simultaneity, manuscript 28. August.

Rigobon, R., & Rodrik, D. (2005). Rule of law, democracy, openness and income. Economics of Transition, 13, 533–564.

Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography, and integration in economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 9, 131–165.

Roth, F., & Thum, A. E. (2013). Intangible capital and labour productivity growth: Panel evidence for the EU from 1998-2005. Review of Income and Wealth, 59, 486–508.

Roth, F., F. Nowak-Lehmann D. and T. Otter (2013). Crisis and trust in national and European Union institutions – Panel evidence for the EU, 1999 to 2012, EUDO/RSCAS working paper series 2013/31, European University Institute.

Saisana, M. and A. Saltelli (2013). Statistical audit. In: M. Agrast, J. Botero, J. Martinez, A. Ponce and C. Pratt (2013). WJP rule of law index 2012–2013, World Justice Project, 193–199.

Smith, A. (1998). The wealth of nations. Oxford University Press.

Schaffer, M.E., & Stillman, S. (2010). Xtoverid: Stata Module to Calculate Tests of Overidentifying Restrictions after xtreg, xtivreg, xtivreg2 and xthtaylor. http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456779.html.

Stock, J. H., & Watson, M. W. (2007). Introduction to econometrics. Pearson-Addison Wesley.

Verspagen, B. (2006). University research, intellectual property rights and European innovation systems. Journal of Economic Surveys, 20, 607–632.

World Bank. (2006). Where is the wealth of nations? Measuring capital for the 21st century. World Bank.

World Justice Project. (2014). WJP rule of law index 2014. World Justice Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendices

1.1 Appendix 1 Operationalization of the Rule of Law

Given the theoretical character of the discussion in this contribution, a promising operationalization of the concept of the rule of law has been offered by the World Justice Project (WJP) (Agrast et al., 2013). The WJP’s working definition of the rule of law is based on the following four universal principles: 1) governmental and private actors are accountable under the law, 2) the laws protect the security of persons and property, 3) the laws are efficiently enforced, and 4) the law is delivered in a timely fashion by competent and independent representatives (Agrast et al., 2013, p. 9). All four principles broadly cover the rule of law’s function of protecting and enforcing property and contract rights, including the accountability of governmental and private agents, the efficient protection and enforcement of property, as well as the timely delivery of justice. The four guiding principles are measured with the help of eight factors: 1) limited government powers, 2) absence of corruption, 3) order and security, 4) fundamental rights, 5) open government, 6) regulatory enforcement, 7) civil justice, and 8) criminal justice—all of which in turn are based on a total of 48 sub-indicators. An aggregation of all eight factors is statistically sound (Saisana & Saltelli, 2013, p. 198) and leads to an index of the rule of law for 20 of the 27 EU countries.Footnote 19 In addition to an adequate conceptualization and operationalization, a comparative advantage of the WJP data, in contrast to other data sources (WGIP), is the fact that the database consists of new data collected from independent original sources (Agrast et al., 2013, p. 19) and that the data have been measured in de facto terms (Agrast et al., 2013, p. 17). Although all of the above-mentioned arguments would indeed indicate the use of the WJP data for this study’s research design, the WJP database has a severe disadvantage: it offers no observations for the time period 1998–2005, as the first wave and pilot study of the WJP was launched as recently as 2009, with only six countries included. Only from 2009 onward was the country sample expanded to cover over 100 countries in the 2012–13 wave (Fig. 3.A2).

In contrast to the WJP database, the WGIP database (Kaufmann et al., 2010) offers times series data from 1996 to 2012. The World Bank’s WGIP defines the rule of law as “capturing perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in and abide by the rules of society, and in particular the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police, and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence”. (Kaufmann et al., 2010, p. 4). The WGIP consists of 84 individual indicators from 23 separate data sources.Footnote 20 The 84 individual questions consist of indicators concerning the enforceability of contracts, the protection of (intellectual) property rights, and the timeliness of judicial decisions, but they also cover rule of law indexes and indicators concerning the respondents’ trust in the justice system.Footnote 21 All single indicators are then aggregated to construct the rule of law indicator by using an unobserved components model (Kaufmann et al., 2010, p. 9). The unit of the rule of law indicator applied to the 214 countries is that of a standard normal random variable and ranges from −2.5 to 2.5 (Kaufmann et al., 2010, p. 9 and p.15). The WGIP began to systematically construct a rule of law indicator from 1996 onward. Starting from a 2-year base in 1998, 2000, 2002, from 2002 onward, the aggregated data on the rule of law continued to be constructed on a yearly basis, with the latest published data stemming from 2012. The WGI data are most often based on experts, perceptions and, similar to the WJP, measures the rule of law in de facto terms. Although the WGI indicators have been criticized on various accounts (Kaufmann et al., 2007), the very thorough and transparent manner in which the authors have set up their rebuttal to the various criticisms (Kaufmann et al., 2007), in the author’s view, has secured confidence in the general validity of the methodological approach and the data of the WGIP. Thus, overall the WGIP indicators fulfill the methodological requirements for their use in the EU context, taking into consideration the methodological background information (e.g., interpreting the data by utilizing the provided confidence intervals within the cross-sectoral and time series data, controlling individual country cases for measurement changes in the time series data, etc.) as pointed out by the authors (Kaufmann et al., 2010, pp. 9–12 and p. 29). Thus, given the lack of time series data from the WJP, the WGI data represent a well-designed alternative with which to measure the rule of law. In addition, it should be mentioned that the WJP rule of law index correlates as high as 0.98 for the year 2012 in a sample of 20 EU-27 countries (see also Fig. 3.A3 in Appendix A3). It thus seems appropriate to conclude that they both measure the same construct on an aggregated level.

As this contribution focuses in particular on the EU, a third data source should not be overlooked, namely data from the new EU Justice Scoreboard as published by DG Justice and Home Affairs (European Commission, 2013a). Most of the data contained within this scoreboard stem from a very detailed report by the European Commission on the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ, 2012) and offer a range of cross-sectional statistics on EU countries. However, since the data were only collected from 2004 onward, similar to the WJP, no adequate time series data are available for the period of interest (1998–2005).

1.2 Appendix 2 An External Instrument for Measuring the Rule of Law in the Context of Development Economics

A prominent instrument to disentangle the causality-related issues between the rule of law and economic performance (log of per capita income), as discussed in the literature focusing on the dichotomy between developed vs. developing economies, has been introduced by Acemoglu et al. (2001). In their seminal study, the authors introduce the variable “settlers’ mortality” to serve as an instrument for the institutional differences (largely property rights) among countries colonized by Europeans. The theory behind this instrument is as follows: depending upon the mortality rate in the various colonies established by European powers, the European settlers would decide to either settle for the long-term or simply to set up “extractive states” in order to obtain a maximum quantity of resources. In countries with lower mortality rates, such as the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, settlers replicated the institutional design of former European countries, stressing the protection of property rights and the introduction of checks and balances against government power. In countries with a high mortality rate, European countries set up extractive states in which little emphasis was placed on ensuring an effective and equitable property rights regime. Given the assumption that the original institutional design persisted even after independence, Acemoglu et al. (2001) utilize the settlers’ mortality rate during times of colonization for the current institutional design (and the rule of law) within a country in order to causally explain a country’s current economic performance. In developing their concept of social infrastructure, Hall and Jones (1999) used a slightly different set of instruments, based on geographical, inguistic, and trade-related variables.

Both sets of literature are focused on the dichotomy between developed and developing economies. Unfortunately, neither of these prominent papers offers a valid instrument for analyzing the impact of the variance of the rule of law on labor productivity growth in an EU country sample. Future research endeavors in this field of research should be devoted to generating a valid and relevant instrumental variable, avoiding the usual weak instrumental bias (Murray, 2006; Stock & Watson, 2007).

1.3 Appendix 3 Selected Statistics

Scatter plot of the relationship between rule of law and business investment in intangible capital (% of GVA) in the EU-25, 1998–2005

Data sources: Data on intangible capital investments are taken from the INNODRIVE dataset (INNODRIVE, 2011). Data on the rule of law are taken from the WGIP (Kaufmann et al., 2010). Data on intangible capital investment are missing for Romania and Bulgaria.

A comparison of four selected indicators of the rule of law—in the four largest EU economies

Notes: The data on “Enforcement of patent & copyright protection” and “Property rights” are taken from the WGIP (Kaufmann et al., 2010) based on the Institute for Management Development’s “World Competitiveness Yearbook” and the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, respectively. The data stem from the year 2005. The data concerning “Stable laws” and “Civil justice effectively enforced” are taken from the WJP (Agrast et al., 2013). The data stem from the year 2012.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between the rule of law indicator by the WGIP and the rule of law index by the WJP, EU-27, 2012

Notes: Data on the rule of law from the WGIP are from Kaufmann et al. (2010). Data on the WJP are from Agrast et al. (2013). Both sets of data are from the year 2012. Cyprus, Malta, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, and Ireland are not represented, due to missing data in the WJP database.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Roth, F. (2022). The Rule of Law and Labor Productivity Growth by Businesses: Evidence for the EU, 1998–2005. In: Intangible Capital and Growth. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86186-5_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86186-5_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86185-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86186-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)