Abstract

Absenteeism of government frontline health workers can prevent access to primary care, including outpatient care, pre- and postnatal care, deliveries, and vaccinations. As rates of absenteeism tend to be higher in lower-income areas, this issue has the potential to exacerbate the socioeconomic divide. Specifically in Punjab, Pakistan, government doctors posted to rural health clinics, called Basic Health Units (BHUs), were found to be absent two-thirds of the time. Health inspectors are employed to visit BHUs at least once a month to collect data from a paper-based register located at each BHU and ensure doctors are present. However, absenteeism of the government inspectors causes this system to break down. This case study follows the implementation of the “Monitoring the Monitors” program, which aimed to replace the paper-based record-keeping system with an app-based system that feeds an online dashboard system (for real-time aggregation and presentation of data). Conducting a large-scale randomized controlled trial, inspection rates increased from 25.5% to 51.9% after 6 months. After a year of operation, inspection rates were 33.8% in the treatment districts and 23.5% in control districts. An A/B test was used to measure the effect of a simple flagging system that notified senior health officials when health workers were absent during an inspection and showed an increase in doctor attendance from 23.6% to 41.3%. The government eventually adopted this system (rebranded as HealthWatch), and it is now one of the many apps being used to monitor frontline service providers.

Based on research conducted by Michael Callen, Saad Gulzar, Ali Hasanain, Yasir Khan, and Arman Rezaee

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Absenteeism

- Health service delivery in Punjab Pakistan

- Public Service Motivation

- Personality and public sector performance

- Field experiment

- Political economy

- Public Service Delivery

1 Development Problem

It is well documented that government frontline service providers such as teachers and health workers are often absent from their posts in developing countries. Chaudhury et al. (2006) conducted unannounced visits to primary schools and primary health centers across six developing countries spanning three continents. The authors found widespread absence, with rates averaging 19% for teachers and 25% for health workers. The authors also found that lower-income areas had higher absence rates, suggesting absence may exacerbate socioeconomic divides. Many studies have since documented similar patterns (e.g., Banerjee & Duo, 2006; Banerjee et al., 2008; Olken & Pande, 2012; Dhaliwal & Hanna, 2017; Finan et al., 2017).

While the specific impacts of absenteeism on outcomes of the world’s poor are less well documented, evidence suggests the potential for large negative impacts from missing workers. For example, Duflo et al. (2012) leveraged cameras coupled with financial incentives to boost teacher attendance in India. The authors found that lower teacher absenteeism translated directly to increased student achievement. Using a nationwide representative sample of public schools in rural India, Muralidharan et al. (2017) found that “investing in reducing teacher absence through better monitoring could be over ten times more cost effective at reducing the effective student teacher ratio (net of teacher absence) than investing in hiring more teachers.”

These seminal studies, as well as anecdotes about absent frontline health workers in Punjab, Pakistan, motivated this case study. Indeed, in November 2011, my co-authors and I conducted surprise, independent inspections of a representative sample of 850 of Punjab’s near 2500 provincial rural health clinics (dubbed Basic Health Units (BHUs)). We found that government doctors posted to BHUs were absent from their facility during open hours two-thirds of the time (Callen et al., forthcoming). This is particularly alarming as BHUs provide primary care for nearly all of Punjab’s rural population, including outpatient care, pre- and postnatal care and deliveries, and vaccinations.

Myriad factors contribute to the problem of absenteeism among frontline workers in developing countries, including poor incentives to show up to work (Callen et al., 2015; Dal Bó et al., 2013); political-economic factors such as patronage (Callen et al., 2016), political alignment (Callen et al., 2020), and/or political turnover (Akhtari et al., 2017); and poor management (Dal Bó et al., 2018; Rasul et al., 2018).

Another factor contributing to absenteeism is a lack of accurate and actionable data. Before the ICT-based program that is the subject of this case study took shape in late 2011, there was an elaborate, colonial-era, paper-based system for collecting operational data on public health facilities in Punjab. This system was similar to those still in existence across many developing country bureaucracies today. The centerpoint of this system is the physical register—log books at each facility that are used to keep diligent records on staff attendance, medicine stock, patients seen, vaccinations given, etc. During their required monthly inspections of each BHU, government health inspectors record aggregate information from these registers on a standard paper form. Once collected, forms are brought to a central district facility, manually entered into a spreadsheet, and aggregated into a monthly report for senior health officials.

While the pre-existing system led to the collection of vast amounts of data, it ultimately was ineffective in the case of Punjab’s Health Department. Registers upon registers were filled. But then they collected dust. According to our independent inspections, only 23% of facilities received their required monthly health inspection prior to November 2011, essentially halting the flow of information from registers to health inspectors and their managers. And what little information did make its way to a District Headquarter was often inaccurate, for the same political economy reasons that allowed health worker absence in the first place (Callen et al., 2015). This could be seen as a self-fulfilling prophecy—data is collected but isn’t used, so there is no incentive to collect good data in the first place, so data isn’t good enough to be used, and so on.

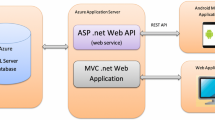

Enter ICT. In late 2011, 2G networks and smartphones had just made their way to Punjab. Zubair Bhatti at the World Bank in Pakistan recognized this as an opportunity to make Punjab’s health data more accurate and more actionable.Footnote 1 At the same time, Punjab’s provincial government had just set up the Punjab Health Sector Reform Program (PHSRP), which had the mandate to push reform within the Department of Health but also had substantial autonomy. PHSRP was run by Farasat Iqbal, a well-respected career bureaucrat in Punjab and someone who was quick to recognize the potential of ICT. He was one of the first champions for the use of technology within the bureaucracy and remained a champion throughout. We partnered with Mr. Bhatti’s World Bank unit and Mr. Iqbal’s PHSRP to take advantage of this opportunity. Together, we designed, implemented, and evaluated a smartphone monitoring program, officially termed “Monitoring the Monitors,” across Punjab’s 36 districts. The program simply replaces the paper-based system of old with an app-based system, otherwise collecting the same data and involving the same health workers. Instead of using paper forms, government health inspectors are equipped with a smartphone and an app to collect data and feed it to an online dashboard system. Cutting out the aggregation step assures real-time information on BHU performance, aggregated into simple charts and tables, for the review of senior health officials.Footnote 2 Importantly, the app also includes several fail-safes to ensure accurate reporting and thus to break the self-fulfilling prophecy described above: reports are geo-stamped and time-stamped and all staff reported present must be photographed with the inspector (Fig. 19.1).

We evaluated the Monitoring the Monitors system through a large-scale randomized controlled trial. Beyond improving the flow of data, the system changed the behavior of inspectors, at least temporarily. In independent audits conducted 6 months after the system launched, the inspection rate increased from 25.5% to 51.9%. After a year of operation, inspection rates were 33.8% in the treatment districts and 23.5% in control districts.

It was our hope that this increase in inspections would increase doctor attendance. On average, this was not the case. But interestingly, we find that the Monitoring the Monitors system did lead to increased doctor attendance exactly in the cases when the system’s data was made actionable for senior health officials. To show this, we built into the system an A/B test of sorts. Specifically, if more than three of the seven health workers that are supposed to staff a rural clinic were absent during a health inspection, we “flagged” a facility as underperforming by highlighting it in red on the dashboard.Footnote 3 We find that flagging increased subsequent doctor attendance from 23.6% to 41.3%. We interpret this as evidence that policymakers do indeed use data when making decisions, if it is made actionable.

This result brings us back to the development problem here—a lack of accurate and actionable data for public sector managers to use to ensure frontline workers show up to work. In this case, ICT ensured more health inspections feeding more accurate data on performance to senior health officials and subsequently much higher rates of government doctors showing up to work in rural health clinics, but only when data on those doctors’ (lack of) performance was actionable.

2 Implementation Context

Pakistan is the world’s fifth most populous country, equivalent in population to all of Western Europe combined. Punjab is Pakistan’s largest province, with over 110 million people. Most of these people rely on free government health services. These are provided by Punjab’s Department of Health, which is headed by the Secretary of Health. The Monitoring the Monitors system facilitates flows of information through the Department’s existing chain of command, so describing that chain is fundamental to characterizing the program.

This provincial Department comprises 36 District Health Departments, each headed by a “senior health official.” Senior health officials are thus in charge of health service delivery for several million people, and they report directly to the Secretary.

Senior health officials are, in turn, each supported by several “health inspectors,” typically one for each sub-district (there are, on average, 3.4 sub-districts per district). Health inspectors are charged with inspecting all of the health facilities in their sub-district at least once every month. Health inspectors are themselves trained doctors who likely began their government service lower down in the bureaucracy.

There are 5 classifications of health facilities, all inspected by health inspectors; we focus on the frontline tier, called Basic Health Units, of which there are 2496 spread throughout Punjab (on average 17 per sub-district). Each BHU is headed by a doctor, who is generally supported by six additional staff. Doctors are general practitioners who have completed 5 years of medical school and are therefore the most trained health professionals in rural areas.

Figure 19.2 depicts this administrative hierarchy.

While we have already discussed general reasons that frontline workers might be absent from their post, in this particular context, it is important to note that doctors also face particularly weak career advancement prospects. Very few doctors rise through the ranks to become health inspectors: compared to the 2496 doctors posted to BHUs, there are only 123 health inspectors. This is not the case with health officials higher up in the bureaucracy. Strong performance by senior health officials is commonly rewarded with appointment to a higher office. Health inspectors are also more likely to move up the ranks.

Another important institutional feature in this context is the fact that it is very uncommon for health workers to be fired from their jobs at any level. However, there are still tools for managers to ensure the performance of their subordinates. In the case of senior health officials ensuring the performance of health inspectors, interviews reveal that they typically begin simply by having a conversation with a problematic health inspector. The next step is to refer the matter to a senior provincial-level official in charge of general administration. This can result in a formal inquiry and ultimately in pay cuts. In the case of health inspectors ensuring the performance of doctors, health inspectors may issue a “show-cause notice,” which requires doctors to explain their absence to senior health officials. In severe cases of persistent absence, health inspectors can transfer doctors to less desirable locations.

3 Innovate, Iterate, Evaluate, and Adapt

3.1 Innovation

While an app that collects data and sends it to an online dashboard may seem trivial today, in 2011 Pakistan, it was novel. The app itself was built using the Open Data Kit open-source platform (https://getodk.org/). As described above, other than the geo-stamps, time-stamps, and pictures, the data collected by the app was not innovative. In fact, it intentionally collected identical data to that collected by the original paper-based forms, to ensure buy-in from the Health Department.

The smartphones required to run the app were the first smartphones that any of Punjab’s 123 health inspectors had ever used. Health inspectors had to be trained to use the phones and app in person, district by district, over the course of more than a month. And there were persistent challenges ensuring smartphones remained charged, working properly, and able to regularly sync data with the online dashboard via 2G networks. This required a full-time staff member to help health inspectors to troubleshoot technical issues and to work directly with phone manufacturers and a major telecom operator in Pakistan.

There was a more subtle innovation with this app in the context of 2011 Pakistan, and this is perhaps the reason this case is in this Development Engineering textbook. That was the way in which the app and dashboard were developed through a partnership between academics, the World Bank, and the Health Department. The idea of an app and online dashboard was not on the Health Department’s radar prior to the World Bank offering the system. And the World Bank-based technology team that developed the system had no experience fulfilling the needs of an entrenched government bureaucracy, such as not changing what data was being collected by the app to allow for sufficient political buy-in. Finally, neither the World Bank nor the Health Department had experience implementing what was essentially a policy reform in a way that could allow for a careful evaluation of its impacts before any scale-up. For example, given the flow of information to senior health officials, it was important to do a clustered randomized controlled trial at the district level. The academics filled this need.

While such a process again may seem trivial today, it was quite innovative at the time, to the point where the system’s technology lead, Asim Fayaz, subsequently started a non-profit center based at Lahore University of Management Sciences with support from Google to repeat the same needs assessment and app design process for other departments of Punjab’s provincial government. This center, the Technology for People Initiative (TPI), went on to design apps for Punjab’s schools, police, courts, and more. Eventually, Punjab’s provincial government’s in-house app development team, based at the Punjab IT Board (PITB), extended the use of mobile apps in many of those departments. PITB developed more than 270 apps for the provincial government between 2012 and 2017.

As stated in Chap. 2, “DevEng integrates the theory and methods of development economics with the principles and practice of engineering, resulting in technical innovations that are tightly coupled with the social or economic interventions required for success in the ‘real world’.” In this case, it was crucial that development economists and engineers at the World Bank, later TPI, came together. There was an added group that was crucial, however—the government—that had to be integrated in the process from the beginning.

One caveat is worth mentioning related to the development of the Monitoring the Monitors app and dashboard—the design approach was very top-down. Few doctors were consulted in the design process, as well as few health inspectors. As a result, once the novelty of the smartphones wore off, many health inspectors were unhappy with the system, and they left their phones at home. Of course, the dashboard allowed senior health officials to pick up on missing data and sanction delinquent health inspectors, ensuring the system continued to operate at a level deemed sufficient. We understand that researchers in fields such as Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) have conducted extensive research to suggest bottom-up app development may often be more effective than top-down (Hartson & Pyla, 2019).

3.2 Iteration

While in the end the Monitoring the Monitors system was relatively straightforward in terms of the data it collected and how it displayed that data (excluding the flagging A/B test built into the dashboard), the design, implementation, and evaluation process required several rounds of iteration.

The app and dashboard design process itself required several rounds of iterations between the World Bank technology team and the Health Department. As mentioned above, this type of direct interaction was new for those involved but ultimately successful. This success can be most attributed to the fact that Zubair Bhatti had served in the civil service in Pakistan prior to joining the World Bank. The understanding that this brought, coupled with sufficient patience, ensured the project did not stall at this stage.

Once a beta version of the system had been built, our research team piloted it in one district of Punjab—Khanewal. Khanewal was selected specifically because the District Coordination Officer (DCO), its highest ranked civil servant, was willing to serve as a champion for the new system within a bureaucracy that was resistant to change, especially if it might involve breaking down existing patronage networks that allowed doctors to shirk from their work. This dovetailed with Farasat Iqbal serving as the system’s champion within the Health Department. That Rashid Langrial had become Khanewal’s DCO shortly before the project launched was luck from the project’s perspective. With his help, we were able to pilot the system in a real-life setting with several health inspectors and one senior health official. This proved instrumental in working out several kinks, especially in the process of training health inspectors and troubleshooting issues with data collection and aggregation. The pilot was also instrumental for final Health Department buy-in. The Department needed to see that the system could work.

The pilot also allowed for us to get DCO Langrial’s perspective on the likelihood of success of the system. He was the one who recommended the dashboard flagging that ultimately proved successful, arguing that the system would be ineffectual unless we made sure those that wanted things to improve had what they needed.

In the last box, we stressed the importance of adding government bureaucrats themselves as key members of the team when turning DevEng toward governance. It is important that these champions have a deep understanding of political realities. It is also important that you identify champions at each step of the project, from design to pilot to the intervention. In our case, we had the head of a reform unit in the Health Department as well as the head of a district as champions. These individuals were critical.

The large-scale randomized controlled trial that followed can itself be thought of as another round of iteration, as we only rolled the system out across half of Punjab for approximately 1 year. We will now discuss this evaluation.

3.3 Evaluation/Results

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Monitoring the Monitors was conducted between November 2011 and October 2012. To collect data for the RCT, independent survey enumerators made 3 unannounced visits to 850 health clinics randomly sampled from the province’s 2496: one before smartphone monitoring began, in November 2011, and two after smartphone monitoring began (in treatment districts), in June and October 2012.

During these unannounced visits, enumerators collected the same information that health inspectors record—information on health clinic utilization, resource availability, and worker absence—as well as information on the occurrence of health clinic inspections themselves. Enumerators also physically verified health clinic staff presence. We also conducted face-to-face surveys with all doctors, health inspectors, and senior health officials in Punjab during the RCT.

We began the experiment after baseline surveys concluded. We randomly selected 18 of Punjab’s 36 districts to receive the Monitoring the Monitors system (“treatment” districts), while 17 districts maintained the status quo, paper-based system (“control” districts).Footnote 4 We randomized at the district level for two reasons. First, the intervention channels information about health inspections to district-level senior health officials. Second, all inspectors in a district are required to attend monthly meetings and so interact frequently, while these relations are much weaker across districts. District-level randomization therefore makes sense in terms of the design of the program and also reduces concerns about contamination.

At the end of the day, the fact that our evaluation leveraged an RCT allowed us to measure the impacts of Monitoring the Monitors by simply comparing inspection and attendance rates in treatment districts with control districts in the post period (our second and third survey waves). Of course, many small decisions were made in the process of conducting the RCT and measuring the impacts of treatment, such as how to select districts for treatment or control (we chose to “stratify” on several variables to ensure the treatment and control groups were as comparable as possible with each other apart from receiving treatment, for example), which empirical specifications to use, how to conduct hypothesis tests carefully, and so on. Details can be found in Callen et al. (forthcoming).

Our results are summarized in Figs. 19.3 through 19.6.

The effect of smartphone monitoring on the rate of inspections. Notes: This figure reports unconditional average treatment effects of the “Monitoring the Monitors” program on the rate of health clinic inspections. The data come from primary unannounced surveys after the treatment was launched (survey waves 2 and 3). The dependent variable is the average inspection rate across clinics within a month prior to the survey. Whiskers depict 95% confidence intervals, calculated using standard errors clustered at the district level. See Table 1 in Callen et al. (forthcoming) for additional details

The effect of smartphone monitoring on doctor attendance. Notes: This figure reports estimated intention-to-treat and treatment-on-the-treated (TOT) effects of the “Monitoring the Monitors” program on the doctor attendance. Effects are estimated from OLS regressions in which the unit of observation is the clinic, and data come from primary unannounced surveys after the treatment was launched. The dependent variable is an indicator for whether a doctor was present at the clinic during an announced visit. All models include randomization block fixed effects. DinD refers to a difference-in-difference specification. IV refers to a TOT specification that estimates the effect of inspections on doctor attendance, instrumenting for inspections with treatment. Whiskers depict 95% confidence intervals, calculated using standard errors clustered at the district level. See Table 2 in Callen et al. (forthcoming) for additional details

The effect of flagging underperformance on the dashboard. Notes: This figure reports on the effect on subsequent doctor attendance of flagging on an online dashboard the fact that a clinic had three or more staff absent to a senior policymaker. Clinics were flagged in red on an online dashboard if three or more of the seven staff were absent in one or more health inspections of the clinic 11 to 25 days prior to an unannounced visit by our survey enumerators. The data sample limits to facility reports in which either two or three staff were absent (the threshold to trigger the underreporting red flag). In addition, the sample is limited to “Monitoring the Monitors” treatment districts due to the necessity of the web dashboard for flagging clinics. All underlying regressions include survey wave fixed effects. Whiskers depict 95% confidence intervals, calculated using standard errors clustered at clinic level. See Table 3 in Callen et al. (forthcoming) for additional details

Figure 19.3 shows the impact of Monitoring the Monitors on inspection rates across our sample facilities. We find that health clinics in treatment districts were 18.1% points more likely to be inspected in the previous month during the treatment period. This represents a 74% increase in inspection rates in treatment districts relative to control districts. Breaking this up into the two waves of post-treatment data collection, we find comparable effects, though there is evidence that the effect of treatment had attenuated by October 2012, a year after the introduction of the program. It is interesting to point out that Monitoring the Monitors still did not achieve anywhere near-perfect health inspector performance. This represents the reality that there are many factors, not just a lack of accurate and actionable data, affecting health worker performance.

We should keep in mind that apps and dashboards are agnostic to political economy realities and that they cannot solve every problem. They might even exacerbate some problems. They are at best thought of as one part of a larger solution toward ensuring public sector absenteeism, or other governance failures, is not a problem in a particular setting. Development economists who choose to tackle issues one app at a time despite larger realities might think of themselves as a plumber engaged in fixing one leak at a time (Duflo, 2017).

Figure 19.4 shows the subsequent impact of Monitoring the Monitors on doctor attendance at BHUs (an explicit goal of the program). We find mixed results here that are highly dependent on our decisions about empirical specification. Conservatively, it seems the program did not have an impact on doctor attendance, on average. That is not to say that it didn’t have an impact in some areas and not others. And, in fact, our flagging results do suggest large impacts when data was made actionable.

Figure 19.5 shows these heterogeneous impacts between BHUs that were flagged as underperforming on the dashboard (those that were likely to draw the attention of very busy senior health officials) and those that were not flagged, comparing facilities just above and below the flagging threshold to ensure the BHUs were otherwise very similar. We find that doctor attendance subsequent to flagging on the dashboard increases by 17.7% points or about 75%. Conversations with government partners suggest that the most likely driver of this effect is verbal reprimands from senior health officials to doctors in charge of clinics.

For our Monitoring the Monitors system to have an impact on doctor attendance, data needed to be made both accurate and actionable. In this case, making data actionable meant making our online dashboard skimmable by high-level, quite busy senior health officials. We did this by drawing particular attention with red highlights to the lowest performing health inspectors and doctors for senior health officials to quickly sanction.

Finally, Fig. 19.6 breaks down the impact of Monitoring the Monitors by two different dimensions than whether a facility was flagged on the dashboard. First, a growing literature documents the role of individuals (as opposed to institutions) in ensuring (or not) the level of public service delivery across the developing world, summarized in Finan et al. (2017). We examine whether personality characteristics of the health workers in our study predict their response to monitoring and to information. To do this, we measured personality characteristics—the Big Five Personality Index and the Perry Public Service Motivation IndexFootnote 5—of all of the doctors in our sample clinics and the universe of health inspectors and senior health officials in Punjab. In Callen et al. (2015), we explore this dimension of heterogeneity in great detail. As an example of the role of personality characteristics in this setting, we present heterogeneity of our flagging results in Fig. 19.6, Panel A. We find that personality characteristics systematically predict responses by senior health officials to our dashboard experiment, as measured by future doctor attendance in flagged facilities: a one standard deviation increase in the Big Five Personality Index of senior bureaucrats increases the effect of flagging on the likelihood that doctor is present at the clinic during a subsequent unannounced visit by 28% points. We see a similar though smaller differential effects of flagging in the case of Public Service Motivation. Of course, these results are merely predictive as we did not randomize personality traits.

Flagging effects by senior policymaker personality and by political competition. Notes: Panel A reports average doctor attendance in clinics 11 to 25 days after the clinic was flagged or not on the dashboard as well as for flagged facilities in districts with a senior health official (EDO) with a Big Five index one standard deviation or higher above the mean. The Big Five index is a z-score average across five Big Five personality traits, elicited through surveys of senior health officials. Panel B also reports average subsequent doctor attendance for flagged facilities in districts with low, medium, and high political competition based on the most recent election. Notes for Fig. 19.5 provide additional details about flagging. Appendix Tables A12 and A13 in Callen et al. (forthcoming) provide additional details about the personality and political competition measures

When seeking to evaluate a program such as Monitoring the Monitors, it is crucial to consider the fact that impacts of the program will likely differ across time, across space, and across individuals. If you stop to develop hypotheses about likely dimensions of heterogeneity from the start (by talking to those who know the context), you will have a chance to test for differential impacts and potentially adapt your program to them before long.

Second, we explore whether measures of political competition predict flagging effects. The bureaucrats we worked with to create the program felt strongly that the program would break down when politicians interfered with senior health officials’ attempts to sanction their subordinates. Indeed, in our surveys, senior health officials report that politicians routinely interfere in this way.Footnote 6 In Callen et al. (2016), we match each clinic in our sample to a provincial assembly constituency and examine in detail the extent to which these political moderators affect the efficacy of the Monitoring the Monitors program. As an example, we find that the treatment effect of flagging on doctor attendance varies by the degree of competitiveness in the previous election. Fig. 19.6, Panel B, presents the results. We find that while flagging increases subsequent attendance by 35.9% points in the most politically competitive third of constituencies, flagging has no apparent effect in the least competitive third. In addition, flagging works better on doctors who do not report a direct connection with a local politician. Indeed, the point estimates, though noisy, suggest the program may have negatively affected attendance of connected doctors.

Taken together, these results drive home that the effectiveness of ICT-based programs such as Monitoring the Monitors very much depends on the individuals making use of the program as well as the political environment in which the program is implemented. Similar findings have been documented in many settings, including by Kentaro Toyama (see Chap. 4). These results also drive home the importance of the Development Engineering framework—the fact that despite the technology is more or less universal, local context is paramount to the effectiveness of potential interventions.

3.4 Adaptation

Perhaps the primary goal of the evaluation of Monitoring the Monitors was to determine the extent to which it should be adapted into a permanent, province-wide policy. The results above suggest the program could be quite effective, but only in certain circumstances. To determine whether the effects were worth the cost, we would have liked to conduct a thorough cost-effectiveness analysis as part of our evaluation. This was not easy, however, since increased inspections or doctor attendance was not the benefits we were ultimately interested in. The ultimate goal was to increase health outcomes for Punjab’s rural poor, outcomes that were too costly for us to measure well in this setting. As a result, we had to rely on one fact about our ICT-based intervention to make a recommendation about continuing the policy or not—it was very cheap to implement. The Monitoring the Monitors program cost 17,800 USD to set up and 510 USD per month to operate.Footnote 7 While the results of the program are mixed, given this low cost, we would expect it to pass a cost-effectiveness test.

Thanks to the excitement of our Health Department partners about this project, we had the opportunity to present the results from our experiment and our conclusions at one of Punjab’s Chief Minister’s (the province’s highest level bureaucrat) monthly health stock-taking meetings. One slide and 1 minute of presenting led to a nod by the Chief Minister. The government of Punjab then scaled the program up to cover the entire province. The hand-off from our team to the government included several adaptations. First, the government rebranded our system to be called HealthWatch, both for design reasons and also so that the government could take credit for developing a new system. Second, the Health Department had to learn how to manage the system. As an example, when we first handed off the system, it crashed for several months, while the Department worked out a process to pay server, airtime, and phone repair bills. Our full-time staff member also spent a great amount of time meeting with those in the Health Department put in charge of HealthWatch to ensure they had the ability to train new health inspectors and to troubleshoot problems with the system.

It is important to understand the goals of politicians and bureaucrats and how they may differ from those of development economists and/or engineers. While academics often care about academic journal publications as a way to impact their discipline (and gain credit toward promotion), bureaucrats may place a much higher weight on photo opportunities as a way to ensure they receive credit toward their own career advancement.

HealthWatch remains in place today, and it is largely the same as first designed. It is unusual for policies and programs to preserve for so long in Punjab as political tides have regularly shifted. We see HealthWatch’s persistence as testament to the strength of the initial Development Engineering collaboration. If any one of the groups involved had attempted to design, implement, and evaluate the program by themselves, it would likely have been unsuccessful. By coming together, we were able to innovate, iterate, evaluate, and adapt our way to a sustainable, impactful program.

The hundreds of similar apps and dashboards that have followed HealthWatch in Punjab can also be considered further adaptations. Some of these adaptations have literally been cut-and-paste jobs. While the photo ops and political payoffs to such apps were high, our observation is that such quick adaptations were much less successful than cases when the TPI or PITB teams repeated the entire process that we followed, including the initial design stage. This is in keeping with best practices in Development Engineering (Chap. 3). We have also observed many online dashboards that failed to take the lesson from our flagging results in making data expedient. Bureaucrats have told us when it takes them too long to browse an online dashboard, they tend to delegate to assistants to create paper reports of what is found on the dashboard. This is a clunky and inefficient process at best.

One final anecdote about adaptation—in a recent trip to Punjab, I met with a government vaccinator. When I asked him about the app he was charged with using to keep track of his performance, he pulled out his phone and showed me not one, not two, but three different apps he was required to open, fill out, and monitor for the same set of activities (on top of registers that are still filled out and kept collecting dust in a closet at the BHU). Because it is so easy to create new apps, PITB and the Health Department have taken to doing so rather than fixing and/or adapting old apps. But the bureaucracy is not as nimble and often still relies on old apps for some time, creating redundancies.

4 Lessons Learned

An investment in developing ICT-based solutions to public sector management problems by Punjab and others like it has driven a revolution in the amount of data that can quickly and cheaply be accessed for policy decisions. This trend is only likely to accelerate with the rise of remote sensing, digital trace (e.g., cell phone call and mobile money transaction records), smartphones, and other research innovations. A key lesson from this exercise is that, appropriately channeled, these data streams can improve policy outcomes.

Other lessons are highlighted in the text boxes above:

-

The Development Engineering focus of bringing together development economists and engineers holds when working to make changes within a government bureaucracy, but there is another group that must also be involved from the beginning—government bureaucrats themselves.

-

It is particularly important to build this political buy-in from the start of a new project. In our case, we ensured buy-in through partnering with individuals with a deep understanding of political realities and through identifying champions within the government at each step.

-

Relatedly, it is important to understand the goals of politicians and bureaucrats and how they may differ from those of the rest of the team. While everyone may agree that health outcomes are paramount, bureaucrats may place a much higher weight on photo opportunities as a way to ensure they receive credit toward their own career advancement. As an academic, it is important to be reminded that many don’t care one bit about an economics journal publication.

-

Relatedly, it is important to understand that apps and dashboards are agnostic to political economy realities and that they cannot solve every problem. They might even exacerbate some problems. They are at best thought of as one part of a larger solution toward ensuring public sector absenteeism is not a problem in a particular setting.

-

For our Monitoring the Monitors system to have an impact on doctor attendance, data needed to be made both accurate and actionable. In this case, making data actionable meant making our online dashboard skimmable and drawing particular attention to the lowest performing health inspectors and doctors for senior health officials to quickly sanction.

-

Finally, when seeking to evaluate a program such as Monitoring the Monitors, it is crucial to consider the fact that impacts of the program will likely differ across time, across space, and across individuals. If you stop to develop hypotheses about likely dimensions of heterogeneity from the start (by talking to those who know the context), you will have a chance to test for differential impacts and potentially adapt your program to them before long.

Discussion Questions

-

1.

The success of Monitoring the Monitors was in part due to building off an existing system of data collection. What if there had been no data collected in the first place as is often the case in these settings?

-

2.

We make the point that it may be important to allow specific politicians and bureaucrats to claim credit for a new app. But we have also seen in Pakistan that apps associated too much with one particular individual or party are quickly removed with political turnover. How can a project strike the balance between political expediency and long-term sustainability?

-

3.

Why bother partnering with governments to create monitoring systems in the first place? We could have created a crowdsourced data collection system outside of the government such as a yelp.com or angieslist.com. Indeed, in follow-up work to this project, co-authors and I did this for government veterinarians to great success (Hasanain et al., 2020). The case study in this book on Protecting Electoral Integrity is another example of a political intervention from the outside. When might it be better to work within the bureaucracy rather than from outside?

-

4.

Relatedly, this case has been about improving the flow of information on health service delivery within the bureaucracy and ultimately the performance of frontline health workers in Punjab. Health services could improve dramatically but still not translate to improved health outcomes for poor Punjabis for many reasons, such as a lack of trust in the government. How could you imagine improving the Monitoring the Monitors system, or coupling it with other interventions, to ensure end-goal improvements in health?

-

5.

As more and more systems such as Monitoring the Monitors are maintained across the developing world, the amount of data available to understand public service delivery outcomes, shortcomings, and the political economy reasons behind such has been growing rapidly. If you suddenly had access to all of PITB’s data, how could you use it to an effect?

-

6.

Imagine you were the Secretary of Health for Punjab and you learned that personality characteristics of bureaucrats and local political competition are pivotal to whether data is used to improve public sector performance. How could you make use of this information to improve health outcomes in your province?

Notes

- 1.

We thank Asim Fayaz in addition to Zubair Bhatti for envisioning and designing the smartphone monitoring program.

- 2.

The data include staff attendance, availability of medicine, patient visits, vaccines provided, cleanliness, and so on.

- 3.

See Fig. 19.1, Panel B, for the red flagging. Note this arbitrary threshold was not known to anyone outside of the research team.

- 4.

Note 35 of Punjab’s 36 districts were in our experimental sample. Khanewal was left out of our sample for the main RCT because it had already received the system during our pilot.

- 5.

Developed by psychologists in the 1980s, the Five-Factor Model, or Big Five personality traits, is now one of the most widely used personality taxonomies in the field. We measure the Big Five traits using a 60-question survey developed specifically in Urdu and validated for use in Pakistan by the National Institute of Psychology at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad. Each of the 60 questions offers the respondent a statement such as “I see myself as someone who does a thorough job” and asks them to agree or disagree with the statement on a five-point Likert scale (disagree strongly, disagree a little, neutral, agree a little, or agree strongly). In addition to measuring Big Five traits separately as the mean response to 12 questions (where disagree strongly is assigned a 1, disagree a little a 2, etc.), all traits are normalized into z-scores and averaged to form a single Big Five index. The Big Five personality traits are agreeableness, emotional stability, extroversion, conscientiousness, and openness. The Perry Public Service Motivation (PSM) battery is designed to measure intrinsic motivation for public service. Also developed in the 1980s, it comprises a total of 40 questions measuring 6 traits—attraction to policymaking, commitment to policymaking, social justice, civic duty, compassion, and self-sacrifice. We similarly combine these traits into one index. See John et al. (2008) for the Big Five measure and Perry and Wise (1990) for the Perry Public Service Motivation measure. See Callen et al. (2015) for more information on these surveys and indices.

- 6.

Based on interviews with all senior health officials in Punjab, we find that 44% report a politician interfering in their decision to sanction an underperforming employee during the previous year.

- 7.

The setup costs included 4470 USD to develop the app and 13,330 USD for smartphones.

References

Akhtari, M., Moreira, D., & Trucco, L. (2017). Political turnover, bureaucratic turnover, and the quality of public services. Working paper.

Banerjee, A., & Duo, E. (2006). Addressing absence. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 117–132.

Banerjee, Abhijit V., Esther Duo, and Rachel Glennerster, “Putting a band-aid on a corpse: Incentives for nurses in the Indian public health care system,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 04-05 2008, 6 (2–3), 487–500.

Callen, M., Gulzar, S., Hasanain, A., Khan, M. Y., & Rezaee, A. (2015). Personalities and public sector performance: Evidence from a health experiment in Pakistan (No. w21180). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Callen, M., Gulzar, S., Hasanain, S. A., & Khan, Y. (2016). The political economy of public sector absence: Experimental evidence from Pakistan (No. w22340). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Callen, M., Gulzar, S., & Rezaee, A. (2020). Can political alignment be costly? The Journal of Politics, 82(2), 612–626.

Callen, M., Gulzar, S., Hasanain, A., Khan, M. Y., & Rezaee, A. (forthcoming). Data and policy decisions: Experimental evidence from Pakistan. Journal of Development Economics.

Chaudhury, N., Hammer, J., Kremer, M., Muralidharan, K., & Rogers, F. H. (2006). Missing in action: Teacher and health worker absence in developing countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 91–116.

Dal Bó, E., Finan, F., & Rossi, M. A. (2013). Strengthening state capabilities: The role of financial incentives in the call to public service. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(3), 1169–1218.

Dal Bó, E., Finan, F., Li, N. Y., & Schechter, L. (2018). Government decentralization under changing state capacity: Experimental evidence from Paraguay (No. w24879). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dhaliwal, I., & Hanna, R. (2017). Deal with the devil: The successes and limitations of bureaucratic reform in India. Journal of Development Economics.

Duflo, E. (2017). The economist as plumber. American Economic Review, 107(5), 1–26.

Duflo, E., Hanna, R., & Ryan, S. P. (2012). Incentives work: Getting teachers to come to school. American Economic Review, 102(4), 1241–1278.

Finan, F., Olken, B. A., & Pande, R. (2017). The personnel economics of the developing state. In Handbook of economic field experiments (Vol. 2, pp. 467–514). North-Holland.

Hartson, R., & Pyla, P. (2019). Chapter 13 – Bottom-up versus top-down design. In The UX book (2nd ed., pp. 279–291). Morgan Kaufmann.

Hasanain, A., Khan, Y., & Rezaee, A., (2020). No bulls: Asymmetric information in the market for artificial insemination in Pakistan. Working paper.

John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In Handbook of personality: Theory and research. The Guilford Press. chapter 4.

Muralidharan, K., Das, J., Holla, A., & Mohpal, A. (2017). The fiscal cost of weak governance: Evidence from teacher absence in India. Journal of Public Economics, 145, 116–135.

Olken, B. A., & Pande, R. (2012). Corruption in developing countries. Annu. Rev. Econ., 4(1), 479–509.

Perry, J. L., & Wise, L. R. (1990). The motivational bases of public service. Public Administration Review, 367–373.

Rasul, I., Rogger, D., & Williams, M. J. (2018). Management and bureaucratic effectiveness: Evidence from the ghanaian civil service. The World Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rezaee, A. (2023). Monitoring the Monitors in Punjab, Pakistan. In: Madon, T., Gadgil, A.J., Anderson, R., Casaburi, L., Lee, K., Rezaee, A. (eds) Introduction to Development Engineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86065-3_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86065-3_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86064-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86065-3

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)