Abstract

Economic development can be driven by large, high-performing firms that provide safe, dignified jobs with living wages. The garment manufacturing industry is a large, economically important sector concentrated in low- and middle-income countries; however, it has been characterized by persistent neglect of workers’ concerns and working conditions. This case study explores whether digital communication platforms, combined with improvements in management, can empower garment factory workers to voice their concerns and have their grievances addressed. We describe a series of randomized experiments testing the effectiveness of different grievance reporting solutions, finding that access to an anonymous complaint service improves worker satisfaction and reduces absenteeism. However, these simple solutions do not adequately address issues around management trust, accountability, and quality. An ongoing experiment explores whether grievance reporting technology, combined with team-based performance incentives for management, can further improve outcomes for workers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Global value chains

- Readymade garments

- Worker voice

- Worker wellbeing

- Grievance redressal

- Environmental social and governance policy

- Randomized controlled trial

- Managerial quality

- Human resources

1 Development Challenge

Across the globe, the apparel industry operates through a vast value chain of both formal and informal workers. This includes farmers that grow cotton, factories that turn fabrics into finished garments, and retail stores that sell these garments to consumers. While retail stores are found in many different parts of the world, most production and manufacturing processes are concentrated in low-income countries. This establishes a certain degree of separation between the retailer and manufacturer and even more between the consumer and the frontline worker.

This disconnect, even if unintentional, can lead to business practices that do not internalize the well-being of workers, and the consequences of this disconnect can be drastic. An extreme example is the Rana Plaza tragedy in 2013, in which over 1000 workers died in a commercial building collapse in Bangladesh, caused largely by persistent neglect of working conditions and disregard for workers’ concerns around building safety.

This case study describes how technology can be used to increase connection and engagement among stakeholders on the factory floor. The solutions we describe hold the potential to increase transparency and accountability for vulnerable workers across South Asia’s garment industry. In the status quo, relationships between workers and their supervisors are rife with frictions, owing to production pressures, gender dynamics, low wages, weak work motivation, low self-esteem, and feelings of unbelonging (particularly for migrant workers). While the relationship between managers and workers – and the extent to which workers feel valued – is a key determinant of firm performance (Adhvaryu et al., 2019; Ashraf & Bandiera, 2018; Bandiera et al., 2009; Hoffman & Tadelis, 2018), these issues are too easily deprioritized by business owners, who often fail to perceive their role in firms’ profitability and long-term survival.

The development challenge of creating high-performing firms that can retain their workers – while providing quality jobs to low-income women – is central to economic growth. We address this challenge through technology that enables responsive and supportive interpersonal relationships among workers and supervisors. Our approach, like many innovations described in this textbook, will combine a software platform coupled with a set of novel iteratively designed organizational management strategies. The result is a solution that is highly adapted across developing country contexts – and one that can achieve impact at scale.

1.1 Establishing Connection: Workers in the Garment Industry

The garment manufacturing industry in many low-income country contexts is highly labor-intensive. It spans both the formal and informal sectors of the economy. Production for multinational retail brands in almost all cases happens in the formal setting where firms hire their employees through contracts and often provide workers with basic benefits such as earned leave and government-mandated (in India) health insurance coverage.

In India alone, the textile and apparel industry employs over 45 million individuals directly, making it the second largest sector in terms of employment after agriculture. The industry has been an integral part of the Indian economy since the seventeenth century, reaching a size of $140 billion in 2018. While COVID has dampened its growth, along with India’s economy as a whole, according to data released by the Confederation of Indian Textile Industry (CITI), the recovery for the domestic market is expected to be quite steep after the pandemic. The domestic market alone is estimated to reach USD 120 billion by 2024.The sector contributes 2.3% to India’s GDP, 7% of the country’s manufacturing production, and 13% of the country’s export earnings.

Protections for Formal Sector Workers in India

In the formal setup of the apparel industry, workers are employed in a setting that requires compliance with both legal regulations and retailer standards for

worker safety. Most workers are hired not on a short-term contract basis, but as full-time employees with workplace benefits such as retirement plans and employee health services. While short-term contracts and informal work do form a part of the industry, this case study focuses on formal workers.

In India, wages for frontline workers are benchmarked to government minimum wage policy, which is largely determined at the state level. The minimum wage consists of two parts – a “basic” portion and a “dearness allowance,” which is intended to allow for cost of living adjustments. The dearness allowance is adjusted every year for inflation, while adjustments to the basic wage level are made roughly every 5 years by the Government of India and commonly result in larger increases than the more frequent inflation adjustments.

Wages are fixed; however, workers are entitled to receive additional compensation if they work overtime. Collective bargaining is allowed, and salaries are negotiated according to company policies and local labor laws. There are several trade unions working for garment factory workers, for example, the Karnataka Garment Workers Union (KOOGU) in the southern state of Karnataka.

Our research team has worked for the past decade with Shahi Exports Pvt. Ltd., India’s largest apparel export house. Shahi operates close to 60 large garment factories in India, employing nearly 120,000 workers. Here, we describe the day-to-day work conditions for Shahi employees.

Frontline workers typically earn minimum wage, which in India is USD 105–135 per month. Salaries are deposited to workers’ bank accounts around the seventh day of every month, usually without delays in disbursement. Working hours and holidays are in accord with national labor laws: work shifts are 9–10 hours long, including a lunch break for 30–45 minutes (depending on the factory). The job is 6 days a week, with a day off on Sundays. Approximately 80% of the total workforce are migrants from rural India, and they send remittances of up to USD 40–55 per month on average to family members in their villages, leaving little opportunity for personal savings.

The majority of the garment manufacturing workforce comprises young female workers who stay on the job for an average of 1 year. Based on data analyzed from our partner firm, almost 50% of migrant workers drop out of the workforce within the first 6 months after joining. The industry’s direct and indirect costs of turnover are high, especially in India. Direct costs are incurred by the continuous need to hire and train new cohorts of workers; indirect costs include regularly disrupted production, reduced productivity due to high absenteeism, and low worker morale.

A typical migrant worker comes to the manufacturing area from a rural district in or outside of their residing state. They often face difficulty in acclimatizing to new language, culture, food, co-workers, and cohabitants – all while being separated from their families and social networks back home. In this unusually high-pressure environment, greater exercise of worker voice could improve well-being and sustain young women’s labor market participation.

In fact, larger garment manufacturing firms that contract with international buyers actually do invest in employee well-being and development. For example, the industry has scaled soft-skills training among workers, and well-being measures have become an integral part of management practice. Some firms also provide medical facilities, child care, and welfare schemes for workers. However, a majority of small garment factories, especially those producing for domestic buyers (or subcontracting for medium and large firms), lack transparency and accountability with regard to working conditions and employment contracts.

Facilities provided by the firm discussed in this case study include free child care in every unit with full-time caretakers, support staff, and nutritious free food; medical center in every unit, equipped with free medication, ambulance, and first-aid services; bank accounts for every employee and secure ATMs on site; support in applying for relevant government benefits; merit-based scholarships for employees’ children; human resource team at all units trained in basic counseling skills including behavior change, working with families, and group counseling; specialized counseling cells in 15 units, with professional counselors; and regular employee engagement programs, cultural events, and festival celebrations.

1.2 Attrition, Voice, and Worker Well-Being

Despite recent improvements in employee benefits, there are significant issues facing Indian garment workers and firms. International buyers expect manufacturers to complete regular social audits, conducted by third-party organizations, yet ironically, this process discourages factory management from keeping records of reported grievances. It also disincentivizes managers from taking strict action on complaints, for fear of unfavorable audit reports (which harm the factory’s business). Operating in a high-pressure manufacturing environment means that worker concerns are overlooked, particularly when taking action compromises production.

Most Shahi workers – about 80% – are women working as frontline machine operators (see Table 13.1). Supervisory roles remain male-dominated. This systemic gender imbalance leads to persistent power asymmetry. In addition, most entry-level workers come from low-income and disadvantaged backgrounds, exacerbating their lack of agency and voice. They have few alternative job opportunities (see Box 13.2) and are therefore hesitant to report legitimate issues for fear of retaliation, which in the extreme can lead to job loss.

Anecdotally, we find that systematic gender imbalance, coupled with an environment of pressure and fear, manifests in the form of shouting, abuse, and harassment on the factory floor. These issues often go unreported and unresolved. Predictably, worker absenteeism and attrition in the garment industry are remarkably high, each averaging between 8% and 10% every month at our partner firm.

Box 13.2: Indian Garment Workers Have Few Outside Options

In an Outside Employment Opportunities Survey conducted at 12 factories of Shahi Exports, we surveyed more than 2300 workers about their wage expectations and about outside job opportunities. The primary outside option was another garment factory job (listed by 37% of workers); for most workers (55%), there is no outside option.

1.3 A Lab for Good Business

Albert Hirschman’s seminal work – Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970) – posits that worker voice and exit, or attrition, are intimately related. Voice is defined as follows:

Any attempt at all to change, rather than to escape from, an objectionable state of affairs, whether through individual or collective petition to the management directly in charge, through appeal to a higher authority with the intention of forcing a change in management, or through various types of actions and protests, including those that are meant to mobilize public opinion.

In this case study, we explore how technology can be used to establish a connection between factory management and workers, in the pursuit of long-term worker well-being. Can technology, combined with novel managerial improvements, empower workers to voice their concerns, grievances, and suggestions? Answering these questions requires us to define worker voice and identify how it can be enabled. We must also explore how to build responsive management practices, how to sustain buy-in for worker voice among factory stakeholders, and how to instill bilateral trust in a method for employer-employee communication.

There are multiple existing means of amplifying workers’ voice in our context – ranging from a worker helpline and suggestion boxes to HR outreach and unionization. Although these mechanisms are at times valuable to workers, they are not often associated with trust; transparency; and, importantly, anonymity. The lack of a reliable, transparent, and anonymous mechanism for enabling voice leaves workers feeling unheard and neglected, leading to attrition. On the other hand, managers in this context lose touch with the pulse of their factories, which in the long run allows minor issues to snowball into larger, more systemic problems.

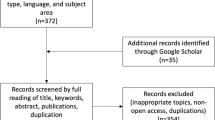

These observations and questions started us on a journey to develop technological solutions informed by human-centered design to promote voice among garment workers with a buy-in from the management. In the first leg of this journey, we evaluated the impact of an employee satisfaction survey, an elementary form of worker voice, on worker satisfaction and attrition. In a second experiment, we leveraged a digital SMS-based worker grievance redressal platform to automate the process. Learning from these efforts and analyzing other worker voice management tools available in the market, we documented how existing technologies fail to fully address needs in the Indian and wider South Asian garment manufacturing context. Finally, we designed a novel, lower-cost solution that leverages digital technology to enable worker voice coupled with managerial incentive programs to promote buy-in from factory staff.

Our resulting worker communication solution, branded as Inache, enables workers to communicate their suggestions and grievances via SMS or voice call, and mobilizes managers to listen and help via system-level incentives. We are currently evaluating the impact of this solution on management outcomes, worker satisfaction, and ultimately worker attrition and productivity.

This journey has also spurred the creation of a nonprofit organization, called Good Business Lab (GBL), which is registered in the United States and India. GBL continues to design, evaluate, and proliferate new workplace technologies and programs aimed at a myriad of persistent workplace issues. GBL also produces insights about the adoption, effectiveness, and paths to scale of these innovations. This chapter describes the evidence generated by GBL for the case of worker voice, as well as documents the multistaged process we follow when engaging in user-centered software design. The journey is far from complete, but as you read, we hope you see the potential impact of this deliberate and innovative approach.

2 Context for the Innovation

2.1 Existing Mechanisms for Worker Voice

The stakeholders that influence worker voice the most are the manufacturers that employ workers and the brands that source from these manufacturers. Typically, corporate brands mandate third-party “audit” of manufacturing factories for compliance with social, environmental, health, and occupational safety requirements. Providing an avenue for workers to voice their concerns, unfortunately, doesn’t take priority in this list. In the rare instance that it does, the requirement is limited to having suggestion boxes on the factory floor, an age-old traditional practice sans a robust proof of concept in the current context. We envision providing such avenues to voice concerns, beyond compliance. However, an unwelcome outcome of the auditing culture has been the general fear of transparency among factories, which gravely affects their willingness to adopt worker voice measures.

To better understand the context, we first undertook a design audit. This involved understanding the organization’s sociocultural fabric and the prevalent norms and rituals – both explicit and implicit. We looked at existing mechanisms to report grievances or suggestions, or ask questions, that a worker had access to, at work. We found that there were several communication channels in place at Shahi (see Table 13.2), and we gathered data on these channels for 40+ factories.

We also studied existing processes and organizational hierarchies to understand factory dynamics. This was done by undertaking focus group discussions with top management leaders, human resources (HR) offices, and production staff members and conducting semi-structured interviews with more than 30 workers, representing different personas (e.g., migrants and locals, married and unmarried, novices and experienced, different job functions). Moreover, we made observations on the factory floor through short ethnographic studies.

We discovered shortcomings with the mechanisms outlined in Table 13.2, including a lack of a formal go-to process, accountability, and transparency in grievance registration. Often, issues raised by workers through direct communication with HR staff were not recorded anywhere. In addition, turnaround time for response varied – from a few hours for direct communication with HR on the shop floor to several months for suggestion boxes and worker committee meetings. Besides suggestion boxes, it was impossible to maintain anonymity through any other mechanisms. This restricted workers from sharing sensitive grievances, like cases related to sexual harassment, verbal abuse, and bullying.

While helplines seemed to be an effective method for registering cases, many workers opted to call after office hours (sometimes at 10 PM or 11 PM, a practice discouraged by firms). Finally, while announcements and handbooks were effective in disseminating information to a mass audience, carrying the handbook and paying attention to announcements during working hours were a pain point, from workers’ perspective. Like suggestion boxes, they also failed to support two-way communication. Help desks were effective in large factories with ample staff (personnel) but ended up being futile in smaller factories with limited staff who felt burdened with excess responsibilities.

2.2 Modeling the Factory Environment

To further build an understanding of people’s interaction with internal factory systems and how they together enable and impact worker voice, we created a model of the factory’s environment. We modeled the “macro” environment, focusing on Shahi’s organizational structure, and the “micro” environment, focusing on the worker’s universe of experiences.

Macro-environment

First, we explored how factory management perceived the value and threat of enabling worker voice. We mapped stakeholders according to their incentives, motivations, and commitment to worker voice. By studying the administrative records produced by stakeholders, we discovered that the factory HR and organizational development (OD) teams were working in tandem to manage grievances. We were able to formulate the roles and responsibilities of each unit, resulting in an organizational structure detailed in Fig. 13.1.

Each factory’s HR team works as an interface between the workers and the management. The HR team is responsible for employment-related procedures, such as salary, attendance, and onboarding workers. The organizational development (OD) team is responsible for implementing worker well-being programs on the ground, for example, maintaining hostel facilities (room and board) for migrant workers, running rural training centers and upskilling programs, and implementing other social compliance programs in the factories. The core team for grievance management in the factory comprises representatives from the HR and OD departments.

After interviewing Shahi’s staff, we were able to map interest in worker voice tools and trace various stakeholders’ levels of influence within the factory. This exercise allowed us to identify “paths of least resistance,” i.e., easiest ways to align stakeholders’ interests with our reforms to management practice.

Microenvironment

To understand the worker’s perspective, we first mapped all of the actors a worker interacts with (see Fig. 13.2), including supervisors, doctors, security guards, hostel wardens, and management staff. We also mapped the nature of workers’ relationship (positive, negative, or neutral) with each stakeholder. In any manufacturing setting, the workplace hierarchy is rigid, and it influences and drives stakeholders in different ways. We tried to reinterpret the hierarchy, incorporating the frequency with which workers interact with each stakeholder. We identified two important loops that exist in this ecosystem: (1) conflict loop and (2) peace loop. The conflict loop (highlighted in red) consists of workers, line supervisors, and other production staff. There exist predictable reasons for conflict, for example, low efficiency, the production pressure of meeting targets, inferior production quality, and skewed gender ratio (most of the workers are female, while their supervisors/managers are men). On the other hand, the peace loop (highlighted in green) consists of workers, HR executives, OD representatives, and medical/healthcare staff. Workers tend to reach out to one of these stakeholders for help or assistance, including mustering emotional support in a conflict or distress situation.

The rest of the factory’s stakeholders don’t interact directly with the workers very often and can be categorized as a neutral group. Naturally, on the shop floor, there is a balancing act between the conflict loop and peace loop.

Apart from the internal stakeholders, there are key external partners – like NGOs, trade unions, government agencies, and retailers – that impact workers in various ways. NGOs and trade unions usually have strong local connections with workers, nurtured over a sustained period of time. They have a reputation of caring deeply about workers’ interests. This lends them credibility, not only among workers but also suppliers and retailers. Government agencies and departments inform state- and national-level policy which affects workers’ day-to-day lives (e.g., how much they earn, regulating factory working conditions such as mandating the requirement of a child care center in factories in India). They have far-reaching networks to undertake widespread information dissemination. Retailers or brands that do business with the supplier often leverage their influence to demand various business practices and measures from suppliers, which directly impact workers, for example, requiring third-party social audits and mandating training programs.

We dug deeper to study a day in a worker’s life – to understand their high and low points – through in-depth interviews with approximately 30+ workers. We used empathy maps, a method used to understand users from what they say, how they feel throughout a day, and how they respond to stressful situations (see Fig. 13.3). This process surfaced the cognitive load imposed by financial strain, especially from instances of delayed wage payments. Such stress, coupled with day-to-day issues, has a tendency to pile up and become a cause of great distress for a worker. We also learned that in this population, very few workers owned a smartphone (approximately 45%). In fact, most workers owned and used feature phones, and only half were formally educated. Of those with formal education, most completed high school only. These observations would impact our tool development significantly.

3 Innovate, Evaluate, and Scale

3.1 Experiment No. 1: A Study of Worker Voice

Firms like Shahi revise their wages frequently. They can choose to raise wages by more than is required by minimum wage, although this is rare. In general, workers face substantial uncertainty about the size of annual wage increases, with unpredictable government and firm decision-making. Anecdotal evidence suggests that worker dissatisfaction is especially high after annual firm-wide wage increases – a fact that may be explained, in part, by the disappointment brought about by wage-related uncertainty.

In our first voice experiment, we investigate how this disappointment might lead to higher quit rates. The firm-level wage hike in this case took effect in April 2016, the same year when the basic component of the minimum wage was revised by the government, which takes effect once every 5 years.

Through a randomized controlled trial, we tested the impact of voice on worker satisfaction. Employee feedback channels are an important form of voice, with both intrinsic and instrumental value. The intrinsic value comes from the ability and opportunity to express one’s opinion about the workplace or workplace practices. The instrumental value is derived from the changes in the workplace resulting from feedback.

We wanted to test whether feedback operates primarily through the intrinsic channel, by providing workers an option to voice their (dis)satisfaction. So, we deployed a simple employee satisfaction survey in the months immediately following the 2016 wage hike.

We selected a sample of 2000 workers, spanning 12 factories, to participate in the study. Approximately half were randomly selected to receive the survey (treatment group), and the other half made up the control group. The survey was anonymized and recorded (1) worker satisfaction with the job, supervisor, wage, and workplace environment and (2) opinions about supervisor quality (e.g., whether mistakes are held against workers, whether it is difficult to ask others for help, whether supervisors encourage learning, and whether workers can trust their supervisors to advocate for them, listen to them, and help solve their problems). For all 12 factories, we also obtained routine administrative data collected by the firm. These included retention rates and personnel data including gender, education, hometown, department, and job type.

Our findings were compelling: many workers used the survey to express dissatisfaction with various aspects of their jobs. As shown in Fig. 13.4, over 20% of workers agreed or strongly agreed with the first two statements: that mistakes were held against them and that asking for help was difficult. Smaller proportions (between 6 and 16%) provided negative evaluations of their supervisor, indicating their supervisors were not encouraging, not someone they could trust, or indifferent about helping solve problems. Combining responses, over 50% of the sample responded negatively to at least one of the six statements.

Reviewing workers’ satisfaction levels, we also gained interesting insights. Though average satisfaction with the job, supervisor, and workplace environment was quite high (over half reported being extremely satisfied), satisfaction with wage levels were much lower. More than half were either somewhat or extremely dissatisfied.

We learned that workers’ expectations were substantially higher than the realized wage hike: they expected a hike that was roughly three times the size of the actual increase. On average, workers expected to earn about USD 17 (16% of total salary) more per month than their realized wages.

Further analysis, combining administrative data on retention, revealed that the effects of the voice intervention were strongest among the most disappointed. Individuals who were disappointed by the wage hike were more likely to quit, but the voice intervention was particularly able to lower quit rates among them. At the average level of wage disappointment (USD 17), those who received the voice intervention were 19% less likely to quit than the control group. For those who were not disappointed at all, the intervention had no statistically significant effect. This set of results (see Fig. 13.5) suggests that the survey voice intervention worked primarily by mitigating disappointment.

3.2 Experiment No. 2: An Off-the-Shelf Software Solution

Encouraging results from the first experiment led us to a partnership with the Children’s Place, a clothing company, to test an existing worker engagement technology platform, called WOVO by Labor Solutions. Through interviews with various stakeholders, we learned that worker voice was undermined by the negative repercussions of raising complaints and the weak accountability for complaint resolution by management. These trends demotivated workers. In addition, existing grievance mechanisms at Shahi Exports (such as suggestion boxes and worker committees) either lacked anonymity or offered no mechanism for ensuring feedback to workers on the status of complaints. WOVO provided both anonymity and accountability.

The platform is built as an SMS-based worker grievance redressal tool, which 1) allows workers to anonymously submit messages (questions, grievances, or suggestions) via SMS (or the WOVO smartphone application) and 2) provides management with a dashboard to respond to manage and gather data about such communication. Our experiment was again designed as a randomized trial, randomizing 7,500 workers in two Shahi factories into either treatment or control. The treatment group was formally registered on the WOVO platform and received user training. The control group had access to the tool and could submit grievances. However, they were neither formally registered on the platform nor did they receive user training.

This study was designed to minimize the threat of spillovers between treatment and control groups. Manufacturing in the garment industry is organized in assembly lines, consisting of 50–70 workers arranged in sequence. Workers are often shuffled between lines. Together, these conditions would have created resentment if some workers were provided with access to a service like WOVO, and others had the service withheld (and only learned about it indirectly). To address this, we sent the treatment group private reminders via SMS, encouraging them to use the tool. No reminders were sent to the control group. This drove variation in tool usage between treatment and control group and helped estimate impact.

To study the impact of WOVO on business and social outcomes, we collected survey data and analyzed administrative records. Enumerator-led surveys were used to capture self-reported measures of worker well-being. More than 2,600 workers were randomly selected for survey follow-up, across treatment and control groups. The survey modules captured worker demographics, satisfaction level, mental health challenges, types of grievances and their redressal, and phone availability and usage. We did two rounds of surveying: at baseline, before the start of the intervention, and at end line, 7 months after the start of the WOVO program. Administrative data included measures of worker productivity, retention, and absenteeism.

In the first experiment, every study participant got an opportunity to answer the survey, which can be interpreted as 100% utilization; in the second experiment, the utilization rate for the technology was just 4.69%. Nevertheless, the results from the second experiment show reduction in absenteeism and attrition across the study population. Absenteeism was reduced by 5% in the treatment group, on a base monthly absenteeism rate of 9.6% in the control group (see Table 13.1). We find that the attrition was 6–10% lower in the treatment group compared to the control group, though these results are not precisely estimated (they are only significant at 10% level for one of the specifications). We interpret this as the impact of access to the tool, irrespective of use. This suggests that the impact of the tool is largely delivered by having the option (i.e., access to feedback) rather than by actual grievance redressal.

During the evaluation period, a total of 354 cases were registered in two factories, representing a ninefold increase in utilization compared with the suggestion boxes posted in factories (which had a utilization rate of 0.52% in the same period). Treatment group workers used the SMS tool about four times more compared to control group workers.

Worker surveys recorded significantly higher trust in the tool among the treatment group. Among treated workers, 84% were aware of the tool, and 92% of all cases registered through the tool were from this group. In comparison, only 55% of workers in the control group were aware of the tool, and only 8% of all cases received were sent by this group. User training and (SMS) reminders administered to the treatment group were able to strengthen trust in the tool by 2%, driving a fourfold increase in utilization.

A summary of the different types of cases registered on WOVO during the study is shown in Table 13.3. The data have been aggregated from WOVO’s raw output and cleaned to remove any test cases by Labor Solutions and Shahi. The greatest number of cases was about provident funds and banking, which are considered to be questions rather than grievances and are not usually considered to be urgent. This suggests that workers leveraged the tool to share routine issues. However, some of these issues require workers to physically visit HR and are out of the purview of HR’s control, e.g., receiving checkbooks or linking mobile numbers to their bank accounts. Nevertheless, WOVO is a useful way to record and track these issues to build a collective case for action (Table 13.4).

GBL invested heavily in qualitative data collection in this study. In a series of interactions with HR managers in the two factories, the team captured rich details on the experience of implementing and using WOVO. Fifteen HR team members were involved in this study; they found the dashboard relatively easy to use and were comfortable using SMS to communicate with workers, ranking it at 4 on a scale of 1–5 (5 being easiest). One-third of the HR staff felt that the type of complaints was different than they were used to, suggesting that workers might be using WOVO to report issues that they didn’t report earlier. Around one-third felt that the total number of complaints through offline mechanisms (like suggestion boxes) had also increased, while 55% felt no change in the number of complaints they had to resolve. More than half felt an increase in their workload due to the tool, since it involved cases that could have been resolved more efficiently if the worker came to speak with them directly (e.g., workers using the tool to enquire about their provident fund may not have provided enough details, like employee codes, in the SMS; this created a communication lag of several days, which delayed processing; when workers drop by the HR office, these issues can be resolved within minutes).

In terms of interpersonal relations within the HR team, 26% felt that relations with their superiors improved, mainly due to transparency of the process. However, 13% felt that due to the expectation of resolving grievances quickly, relations worsened. Over half felt that the tool brought about a positive change in the HR culture, one-third felt that work culture remained the same, and 6% felt it had deteriorated the culture. They felt an increase in the need to actively solve grievances and experienced a better connection with the workers.

With respect to utilization of the service, we realized that restricting communication to only SMS service, as permissible on the WOVO platform, was suboptimal, given the limited (digital) literacy of the workforce. In our baseline survey, we found that only 45% of workers owned smartphones, and only 54% had completed high school. Most workers owned and used feature phones. Strictly, SMS-based communication further affected each step of the user journey. For example, workers use Roman and regional language script depending upon the configuration of their feature phones. As per tech specifications, 1 SMS = 150 Roman alphabets = 90 regional language alphabets. Thus, each grievance could take up to 2–3 SMS, and each SMS could cost 0.5–1 INR. The costs can double quickly if back and forth is needed to resolve a complaint, discouraging workers from reporting sufficiently or reporting at all.

The consensus among managers was that existing job roles of floor managers needed to be leveraged to troubleshoot and increase the speed of the redressal process. For example, if a manager is responsible for handling canteen-related complaints, then that manager needs to be involved in the resolution process for related complaints. This decentralized troubleshooting would enable smoother and quicker grievance redressal and seemed preferable than having a single centralized “super administrator” for a factory.

Usage climbed once workers developed trust in the service. Historically, traditional grievance management systems together brought in 400–500 cases in 3–4 months across all 60+ factories. With WOVO, across just two factories, the increase in registered cases was sizable, with over 300 cases lodged in 7 months. In collaboration with ex-labor officers and legal experts, GBL designed and delivered capacity-building workshops to the management, in order to resolve and manage the increased caseload efficiently and effectively.

Managers felt that the tool brought workers closer to the management, yet they underscored the need for an incentive system to encourage managers to execute the tool properly, including taking action on incoming grievances. To this end, they suggested introducing nonmonetary incentives, alongside the tool.

3.3 Experiment No. 3: A Custom Solution

After two (impactful) experiments with our research team and with intensifying dialogue about worker engagement, Shahi became committed to the idea of transparent, digital worker management communications. However, the implementation of WOVO highlighted key areas where the product fell short of Shahi’s needs, including incompatibility with voice call features and the high per-worker cost of subscription to the software platform. With Shahi’s scale (employing more than 100,000 workers), a subscription service would be a large recurring cost for the business and likely unsustainable. Thus, while there was buy-in from management to implement digital tools, it made sense for Shahi to develop a custom software solution for its 60 factories, tailored to the realities of the Indian garment industry. Shahi asked our design team to develop a worker voice solution from the ground up.

We undertook several qualitative methods to approach the design and functionality of the tool and its implementation strategy. The first step in this process was to understand user behavior, for both workers and managers. We dug deeper into Shahi’s macro-environment to map stakeholders’ incentives, motivations, and commitment to worker voice. We looked at benefits and limitations of the existing mechanisms a worker has access to, to report grievances or suggestions or ask questions at work. We used design thinking methods to learn about the problems workers face at the workplace and understand what holds them back from sharing their grievances. We mapped a day in a worker’s life, especially the highs and lows in a typical day, conducted in in-depth one-on-one and group interviews; tried to gauge how they feel through empathy maps; and assess how they respond to stressful situations (described in detail under Sect. 2).

To provide access to more workers and in turn drive utilization, there was consensus to build a voice call feature, along with messaging feature, to report grievances. There were, however, two options to operationalize it. First, through interactive voice response (IVR) by staffing a call center, centrally or in an individual factory, that can receive and respond to grievance reporters (workers) in real time. Having a person at the other end to record grievances would ensure a better experience for workers and clear reporting. A central call center would be less costly and efficient than a factory call center, but a factory call center would be preferred with regard to language, context, and access to sensitive data.

The second option was to have separate phone lines for different factories through which each grievance is recorded as voicemail which will be transcribed by a designated staff member during office hours. With this option, workers will still be able to send queries 24×7, but management would only be able to respond during business hours.

We decided to go with the second option because, if IVR was leveraged, a worker would be instructed by a computer-generated audio to register their complaint under the right category and subcategory; for example, press 1 to register a complaint regarding the Canteen, and press 2 to select subcategory. Given that we have eight case categories and 25+ subcategories, from a behavioral perspective, we deemed this could create frustration among workers who are incidentally in a distressed state when they call. In addition to that, the attrition rate among production workers stands at 8–10% per month, so technically, after a year, there is a new cohort of workers on the shop floor. After leaving the factory, most workers are supposed to receive their provident fundFootnote 1 (PF) and other savings, implying that a huge number of cases that a factory receives are related to PF, gratuity, etc., and these cases are most efficiently handled by direct factory representatives. Moreover, workers frequently change their phone numbers making it harder to track their complaints. Thus, the decision to provide a separate phone number (option B) to each factory would provide a single point of (familiar) contact in the factory to each worker and would facilitate an understanding of the pattern of such cases in each factory. This choice facilitated accurate mapping and tracking of factory-specific cases, allowed us to design a pertinent performance incentive model for HR (covered presently), and led to devising a decentralized grievance management, which meant that individual factory management would be responsible for managing complaints received from its facility, in effect empowering and encouraging management in the respective factories.

Keeping in mind the low worker literacy, including digital literacy, and minority ownership of smartphones among workers, we realized that the tool needed to be accessible outside of an Android or iOS ecosystem. Multiple regional languages are spoken across different states in India. For example, in Karnataka, 58% of the workers speak Kannada, 15% speak Hindi, 9% speak Oriya, 5% speak Tamil, and 8% speak Telugu. This meant that the tool needed to be compatible with all local languages spoken by workers in a factory.

To improve uptake and buy-in from factory managers, we worked with them to design the dashboard for our tool. We leveraged their familiarity with online platforms such as Facebook and G Suite to build a familiar and easier dashboard user experience. For example, the user interface is inspired from the habits of the software user on social media platforms, e.g., uploading a document in the evidence section and ability to comment.

Software or digital tools are revered for bringing transparency and accountability in the reporting process; however, an important factor in the success of any grievance management system is building trust through timely case resolution. To facilitate this, we made sure that grievance handlers are notified, via email, as soon as a new case is received on the portal. To bolster accountability and action, regular performance review reports are generated and shared with factory heads, overseeing grievance redressal. This ensures that cases are resolved within a stipulated time and workers get regular updates on the status of their complaints.

To further tackle concerns regarding timely resolution and accountability among managers, we designed performance-based incentives for grievance handlers, an idea that was suggested by the HR itself in the qualitative findings from our second experiment. The incentives were nonmonetary in nature because (a) there are multiple programs that run in these factories at any given time, now and in the future, and providing monetary incentives for one particular program might affect expectations of future programs as well, and (b) we wanted to develop a sustainable model that can be easily replicated in other factories. In fact, literature supports the idea of nonmonetary incentives as being effective in increasing performance among employees as discussed by Sonawane (2008) and Sorauren (2000).

Factory representatives shared that recognition and acknowledgment of their efforts by peers, workers, and senior management were a credible motivator. Suggested nonmonetary incentives were achievement certificates, free dinner for family, a recognition email by factory heads, etc.

Finally, we came up with a nonmonetary individual performance review system, which was, however, ceded for team incentives that the management found to work better as it was a team effort (Bandiera et al., 2009; Hamilton, 2003). Moreover, healthy team dynamics was favorable to remove the problem of free ridership and ensure within motivation rather than it being enforced on anyone by their superiors.

Another critical element to build trust in the process was to ensure that the quality of grievance redressal was up to the mark. To this effect, we introduced certain parameters like tone of conversations with the workers and quality of evidence uploaded on the tool. This reduced subjectivity in quality testing and enabled quality checkers to decide whether the case was resolved in a satisfactory manner or not. If not, they had the option to reopen that case, which would subsequently affect factory’s performance incentives. For example, if the number of cases reopened for a particular factory in a month exceeds 10% of total cases, the factory loses out on incentives for that month.

All these shared insights from the design exercise, along with the learnings from the prior experiments, guided the development of our homegrown worker voice solution, Inache (Fig. 13.7).

Inache is a two-way communication tool for workers to anonymously communicate grievances and suggestions via SMS or call to the management. Incoming grievances are managed on the Inache dashboard by a management representative group in a factory, called the grievance handling team or the resolution team. This team is made up of case reporter (CR), case manager (CM), and case troubleshooter (CT). CR is responsible for transcribing and interpreting the voice note or SMS received on the dashboard; this process generates a case incidence report (CIR). Once a CIR is prepared, the case is transferred to the CM who then assigns the case to a CT, well positioned to resolve the grievance (Fig. 13.8).

To ensure timely resolution and accountability among managers, we have designed team performance–based incentives. Workers and managers are given user training and related information on Inache during induction sessions preceding its rollout. We have set parameters in place to test the quality of grievance redressal. In fact, the software automatically generates performance reports in real time; it also alerts if any predefined tolerance levels of quality are breached.

3.4 Limitations and Future Developments of Inache

Currently, the software (HR dashboard) is only supported on the web and optimized for a desktop computer. Most users like case managers and troubleshooters, however, spend the bulk of their time on the shop floor, preventing them from engaging with the tool when they are not in front of their computers. Hence, there is a need for a mobile optimized version, which simultaneously calls for looking into data security for when the user is not in factory premises or the handheld device is not in the user’s possession.

Further iterations could include an artificial intelligence-based chatbot, which is capable of understanding different accents and of resolving simple, day-to-day grievances, like how many number of leaves are pending for a worker.

Having interactive kiosks for workers in the factory can drive engagement, providing a friendly touch point for workers, since they are familiar with ATM kiosks. These kiosks can be placed near medical facilities, HR offices, canteens, etc. While having kiosks in the premises takes away from the perception of complete anonymity, we believe that workers will be willing to use them to register those grievances, which do not jeopardize their safety, for example, banking- and salary-related cases, which cannot be solved without details of the worker, and cases related to canteen, maintenance, etc. Furthermore, having kiosks in the premises can serve as a reminder for the existence of Inache and can signal management’s commitment to worker voice. Having said that, we will work toward designing best practices, placement of the kiosks, and user interaction to provide maximum anonymity.

We piloted Inache in three factories for 4 months before the final rollout, in which we tracked (a) number of cases registered daily; (b) average time taken for the case to travel from one team member to another, i.e., from case reporter (CR), to case manager (CM), to case troubleshooter (CT); (c) average time taken to respond to the worker; and (d) average time taken to resolve the issue and close the case in the dashboard.

The decentralized grievance management required 4–10 people to be a part of the resolution team in a factory. Faced with paucity of manpower, we decided to roll out the main intervention in a phased manner. The first phase involved those factories where sufficient staff existed to handle the tool rollout and where no new hires would be necessary. The second phase involved the remaining factories where new hires would be needed.

Real-time feedback from the users – case reporter (CR), case manager (CM), and case troubleshooter (CT) – in pilot factories helped strategize the composition of grievance handling teams in each factory, depending on its size (number of workers) and design user (CR, CM, CT) training modules. To select the respective grievance handling teams, we created a core committee of senior members from the OD team, allocating each one of them a cluster of factories. This committee was then responsible for nominating suitable candidates from each factory to work on case resolution and giving them user training.

Hackathon

During phase two rollout, we organized a 2-day hackathon with all the stakeholders involved in the implementation of the tool to highlight the issues they were facing and discuss potential solutions. The goal of this exercise was to learn about their day-to-day usage of the tool and identify the need to refine features and develop a standard operating protocol for the users. We learned the following:

-

Workers were testing out the tool by sending in greetings like “hi,” “hello,” “hey,” and “good morning.” This made it difficult for grievance handlers to interpret it or decide if they needed to respond. Not responding could breed distrust among workers.

-

While using the voice note feature to send in grievances, some workers misunderstood the feature to be a customer support-type service and kept waiting for someone to assist them on the other end.

These issues were overcome by giving live demos to around 35,000 workers and explicitly mentioning that the voice note feature was simply another way of sending a message, not a customer support service.

To measure the social and economic impacts of our technical innovation (Inache) and the implementation strategy, we designed a randomized controlled trial. This experiment spans 42 factories which will be divided into the following groups: (1) pure control group: this cluster of factories maintains the status quo, i.e., they do not get the tool, user training, or performance incentives for the managers; (2) grievance tool–only group: this treatment group gets access to the tool and user training for workers; and (3) grievance tool and incentives group: this treatment group gets the whole suite of services, i.e., tool, user training, and performance incentives for the managers. The intervention is at the factory level, in which each worker in a factory gets access to the treatment/control assigned to that factory.

To measure worker well-being outcomes, we will survey randomly selected 36 workers from each factory on themes, such as loyalty toward the company, feedback on their supervisors, workplace satisfaction, trust on redressal mechanisms, and availability of outside job options. To measure business outcomes, administrative data on productivity, attrition, and absenteeism will be collected and tracked.

Challenges with Worker Surveys

Our worker well-being outcomes are primarily informed by one-on-one surveys with workers. In prior experiments, we have found that the majority of responses by workers have been tipped toward a positive/favorable scale. To understand what might be leading up to this, we piloted various versions of the survey on the field – ranging options from five-point Likert scale to three-point Likert scale and from human face emojis to WhatsApp emojis – to elicit honest responses. Out of these piloted versions, we have found the three-point scale WhatsApp emojis to work the best:

Fig. a

The physical survey environment also played a major role in this decision – most surveys are conducted inside the factory, albeit in a separate room away from their supervisors and fellow workers, and we found that it was easier for workers to point to the appropriate emotion rather than saying the option out loud, especially if they had an unfavorable opinion about their workplace, wages, supervisors, etc. Additionally, we kept the questionnaire short (about 15–20 min) to make sure we minimize survey fatigue among workers and surveyors.

We trained surveyors in this new style of questioning by using sample questions/scenarios so that the surveyors knew how to present various options to the worker.

The experiment is still underway at the time of preparation of this chapter. Inache has completed 7 months in the treatment factories, and while we cannot talk about its impact on workers and business right now, as of October 2020, the cumulative utilization rate (total cases/total workers*100) is at 3.19%, and more than 2000 total cases have been received from a total of over 60,000 workers.

At this stage, it is useful to bring the reader’s attention to the lesser absolute number of the utilization rate in this experiment compared to the second experiment (utilization rate of 4.69%). While the present number is smaller, it is not necessarily indicative of lesser impact. Firstly, the context of the two experiments is vastly different; the second experiment was situated in the factories in a northern Indian state, while the current one is situated in the southern states, implying innumerable differences in the types of issues faced at the workplace, gender and social norms and language and ethnicity, among others. Next, until early February, only phase one factories, i.e., a total of 14 factories and 38,000 workers, had access to the tool, so the utilization rate takes the denominator 38,000. As shown in the graph, between the start and early February, the utilization rate went up at first with the access to a better tool but later came down as one-time or irregular issues were resolved satisfactorily. Post February, the tool was rolled out in phase two factories also, and the denominator for calculating the utilization rate took the value of 65,000 (all workers). The second wave of drop in utilization rates around March–April was seen due to a COVID-induced nationwide lockdown, and since then, however, the utilization has been increasing.

Fig. b

The pandemic has certainly heightened worker anxieties by introducing numerous uncertainties, and it poses a big challenge for our work. It might impact the outcomes of our study both directly (attrition due to reverse migration) and indirectly (anxious workers with low productivities). Even barring COVID, we need to investigate how to justifiably calculate the impact of the tool – which questions to pose, which metrics to track, etc. We need to probe how to interpret the utilization numbers in terms of tool effectiveness and which matrix to use for measuring the effectiveness.

The theory of change suggests that deploying an anonymous grievance redressal tool will encourage more workers to submit suggestions, queries, and complaints. Assuming Shahi continuously monitors the implementation and managers’ incentives are well aligned, higher usage by workers could drive responsiveness and redressal by managers, thereby increasing workplace satisfaction among workers. Moreover, the results from the earlier experiments suggest favorable business impact of voice, like reduced attrition (Adhvaryu et al., 2019) and reduction in absenteeism (Boroff & Lewin, 1997). If proven, this project has the potential to provide a positive return on investments for Shahi and will be a testament for adoption in wider industries as well.

4 Lessons Learned

It is valuable for businesses to provide its workers an opportunity to voice, and technology can make this possible by bringing transparency, anonymity, and speed. We witnessed this firsthand when comparing the analogue heavy-handed “employee satisfaction survey” from the first experiment to a digital solution employed in the latter experiments.

During the second experiment, we realized that without contextual understanding, it is challenging to choose an appropriate technology suitable for workers in the low-income setting. In addition to that, scaling existing worker voice solutions in the market was not feasible because of high subscription fees or the technology not best suited to our context. So, we decided to develop the solution in-house. Given the scale of Shahi, employing upward of 100,000 workers in India, the costs of developing its own solution seem justifiable. But we couldn’t have ruled out the existing solutions or undertaken a successful innovative feat if we had not engaged in rigorous, early-stage experimentation.

This endeavor led us to ask important questions, which a solution must answer to be able to fulfill the needs of the workers and the business. What’s in it for them? Value proposition for each stakeholder is different and needs to be prepared and communicated aptly. Our bottom-up approach to development, which touched stakeholders from all levels, yielded a sense of ownership among them, playing an important, mostly favorable, role in case resolution and Inache’s sustained use. We observed the constraints workers face and how their reporting behavior changes in the advent of worker voice technology, and we carefully studied the role of the employer, specifically HR, in influencing this behavior. In the process, we also realized that simply developing a technical solution would not adequately address the more fundamental issues around trust, accountability, quality, and incentives. Therefore, our offering extends to other processes of grievance management than just reporting, recording, and tracking architecture, with, namely, team-based performance incentives for the management and quality control benchmarks.

Gender

The garment industry in countries like India and Bangladesh faces a particular conundrum – even though the majority of the workforce it employs is women, one rarely sees women in higher managerial positions. This trend is a consequence of prevailing gender norms and patriarchal inertia in such regions. Most of the women start and end up as frontline tailors. This disproportionate gender representation at managerial levels affects a factory’s culture – it dampens career aspirations for women and often perpetuates a culture of discrimination in the industry. In such a gendered environment, the role of a communication tool like Inache is to give voice to these women workers. The ability to express themselves, air out their grievances, and hold their supervisors accountable is an effort to address the challenges that larger structural hierarchies pose. Inache, as a worker voice communication tool, becomes an enabler for workers to access systems that are designed to provide aid and support them.

Pivots

Two-way communication and anonymity are the biggest incentives for workers to use worker voice technologies as an alternative to traditional grievance redressal mechanisms like suggestion boxes. There exist several worker voice technological tools; one such tool, WOVO, was evaluated by GBL. This evaluation established the necessity and importance of worker voice interventions in a factory setting. However, the evaluation also highlighted the limitations such technology poses because it was not developed keeping a factory setting in mind. The evaluation brought forth the challenge of limited penetration of technological literacy among the workers. In our baseline survey, we found that only 45% of workers owned a smartphone and 54% of workers had a high school diploma. Another limitation of such tools is that their expense is often not sustainable for a company of Shahi’s size and capacity. The only way to move forward and inculcate the use of worker voice technologies within factory settings is to design a tool, keeping the factory ecosystem in mind. To this end, a voice call feature was included for workers who did not feel comfortable sending SMSs. Additionally, the low-level technological design of Inache meant that it could be used on basic feature phones as well.

A Day in the Life: Stories from Two Garment Factory Workers

Financial strain is often felt more by those under the pressure of time . Devi (name changed to preserve anonymity) called Inache helpline number with one such grievance over her provident fund (PF) loan. She recounts in disbelief how fast she received a confirmation message replete with a case number to identify her issue, sans any lag. For workers like Devi, getting used to procedural delays is almost a survival tactic, but its absence, she candidly shares, brought solace, long before the issue was resolved. Within 2 days of registering her grievance, she received a message asking her to share further details. Soon after, she was requested by the HR department to meet the accounts department who resolved all her queries on the pending PF Loan. Paperwork followed, and within a week, her need, urgent at the time, was resolved on priority.

Day-to-day issues, though minor, can pile up and become a cause of great distress. Sheila (name changed to preserve anonymity) shares how she requested for an extra trolley in the dispatch department through the Inache helpline number. The HR department followed up the next day, understood her requirements, and made the necessary arrangements within a few hours. Sheila was elated with the timely resolution – it made her work easier, increased her trust and reliability in the system, and improved her appreciation for the employer.

Changing Technology and Political Landscape

The mobile technology landscape in India is under rapid transformation today. While some changes affect us favorably, others could necessitate overhaul of our service offerings. Hereunder, a few key macro-level developments are mentioned that are currently underway. It remains to be seen how they will affect the development of our new marketable versions:

-

In India, the telecom market is a red ocean, where different players try to outcompete with each other through price. Every month, telecom operators come up with new data and voice call plans. This is especially attractive to low-income populations that are highly price-sensitive, thus switching from one operator to another in a short span of time. This is a major issue in maintaining a stable worker master data, which maintains workers’ phone numbers that are registered in the Inache platform. When a worker instead chooses to use a new, unregistered phone number to file a complaint, it could create confusion about the authenticity of the cases. We tend to receive many cases from unregistered phone numbers. To overcome this, we try to frequently update the worker master data. We also try to keep workers informed about the importance of maintaining the same phone numbers for longer periods during training, and we even do short refresher training frequently to this effect.

-

Today, prices of feature phones and smartphones are comparable. Google has introduced low-cost Android Go-powered smartphones for emerging markets like India. Despite this, smartphone adoption rate among women remains low in India because the decision to buy (or not buy) a smartphone still rests with the head, primarily husband or father, of the family who perceive it as an item of leisure. Low smartphone penetration prevents us from leveraging mobile applications, which could be instrumental in creating a more engaging platform for workers. If during the RCT, which is underway, a majority of Shahi’s workforce switches to owning a smartphone, we will look into developing a mobile app for Inache.

-

Recent developments in the telecom industry in India, for example, the rise of Jio and merger of Idea-Vodafone, have affected the quality of phone services in general. Telecom is moving from 2G/3G to 4G, while the adoption rate of 4G phones is really low among our targeted population. This means that most workers are using 2G/3G phones with teleservices that are 4G phone compatible. This adversely affects the SMS delivery rate, with approximately 70% success. While there is not much we are able to do to tackle this right now, we are looking into other network providers, which have better success rates.

-

The Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) regulates the telecommunications sector in India. According to which, an enterprise is not permitted to receive and send an SMS from the same phone number. This means that the phone number, which the worker uses to report grievances, cannot be used by the factory to contact the worker. Instead, the factory has to use a different phone number to respond, which we eventually did, and this can lead to confusion and apprehension among workers. We try to inform workers of this peculiarity, via demonstrations, during the training sessions.

Discussion Questions

-

1.

Why does the problem of trusted communication mechanisms on factory floors still exist? What other solutions or mechanisms could accentuate Inache’s intended outcomes?

-

2.

What are the pros and cons of decentralized grievance management mechanism?

-

3.

Suggest some innovative ideas to utilize technology in low tech literacy contexts.

-

4.

Discuss monetary vs nonmonetary incentives for case managers.

-

5.

Discuss additional hypotheses/treatment arms which can be tested in a similar setting.

-

6.

Can you draw any parallels between enabling voice on the factory floor and enabling voice in your own university/work setting? What has/has not worked for you?

-

7.

In the system of factory communication, can you identify negative and positive loops that either curb or enable worker voice?

-

8.

Beyond business returns highlighted in this case study, can you identify some inherent moral reasons for enabling worker voice?

-

9.

What could be a better approach to introduce digital tools to this population (workers and managers)?

-

10.

Can you imagine any spillover effects on other areas, not already mentioned, of using Inache in this setting?

Notes

- 1.

Provident fund (PF) is an investment fund contributed to by employees, employers, and (sometimes) the state, out of which a lump sum is provided to each employee on retirement. Many workers leave their jobs after 5 years of service, at which point they are entitled to PF and gratuity benefits. Recent guidelines by the Government of India suggest linking of bank and PF account number to Aadhar Card, PAN Card, and mobile phone number. Sometimes, this process proves to be a pain point for workers. Hence, we consider issues related to PF and other schemes as major severity cases.

References

Adhvaryu, A., Nyshadham, A., & Tamayo, J. A. (2019). Managerial quality and productivity dynamics. No. w25852. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ashraf, N., & Bandiera, O. (2018). Social incentives in organizations. Annual Review of Economics, 10, 439–463.

Bandiera, O., Barankay, I., & Rasul, I. (2009). Social connections and incentives in the workplace: Evidence from personnel data. Econometrica, 77(4), 1047–1094.

Hoffman, M., & Tadelis, S. (2018). People management skills, employee attrition, and manager rewards: An empirical analysis. No. w24360. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Expectations, Wage Hikes, and Worker Voice: Evidence from a Field Experiment-Achyuta Adhvaryu, Teresa Molina, Anant Nyshadham (2019). https://www.nber.org/papers/w25866.pdf

Boroff, K., & Lewin, D. (1997). Loyalty, voice, and intent to exit a union firm: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 51(1), 50–63.

Sonawane, P. (2008). Non-monetary rewards: Employee choices & organizational practices. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 44(2), 256–271.

Sorauren, I. (2000). Non-monetary incentives: Do people work only for money? Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(4), 925–944.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Adhvaryu, A. et al. (2023). Amplifying Worker Voice with Technology and Organizational Incentives. In: Madon, T., Gadgil, A.J., Anderson, R., Casaburi, L., Lee, K., Rezaee, A. (eds) Introduction to Development Engineering. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86065-3_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86065-3_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86064-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86065-3

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)