Abstract

South Africa has one of the highest rates of youth unemployment and under-employment around the world, despite having a relatively large formal sector. This is driven, in part, by frictions in labor markets, including lack of information about job applicants’ skills, limited access to job training, and employers’ reliance on referrals through professional networks for hiring. This case study explores whether the online platform LinkedIn can be used to improve the employment outcomes of disadvantaged youth in South Africa. Researchers worked with an NGO, the Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, to develop a training for young workseekers in the use of LinkedIn for job search, applications, and networking for referrals. This intervention was randomized across 30 cohorts of youth, with more than 1600 students enrolled in the study. The research team worked with LinkedIn engineers to access data generated by the platform. The evaluation finds that participants exposed to the LinkedIn training (the “treated” participants) were 10% more likely than the control group to find immediate employment, an effect that persisted for at least a year after job readiness training.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Labor supply

- Labor demand

- Human capital

- Unemployment

- Job search

- Firm employment decisions

- Human development

- Online platforms

- Job readiness training

- Digital professional networks

- Youth employment

1 Development Challenge

In developing countries, the system of paid labor is characterized by a duality of informal and formal jobs. Work in the formal sector is tied to employers that are registered with the government and pay taxes. In contrast, work in the largely unregulated informal sector often involves self-employment or employment with family-owned enterprises. For example, small-scale street vendors, taxi drivers, and freelancers are typically part of the informal economy. Although wages tend to be higher and less volatile in the formal sector, the informal sector comprises 60% of all nonagricultural employment in most countries in the Middle East, North Africa, Latin America, Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa (ILO, 2018; Kingdon & Knight, 2001). Relative to other developing countries, South Africa has a large formal sector and a high rate of unemployment (Statistics South Africa, 2019).Footnote 1 This case study examines the application of existing technology to mitigate barriers between young South African workseekers and formal employment opportunities with government-registered enterprises.

In the first quarter of 2019, approximately 28% of South Africans were unemployed (Statistics SA, 2019). South Africa’s high aggregate unemployment is due to a combination of factors, including spatial segregation between workers and firms, labor regulations, a weak education system, racial discrimination due to the legacy of apartheid, and restrictions on informal enterprises (Banerjee et al., 2008). The spatial mismatch between where jobs are located and where workseekers live increases the time and monetary cost of submitting applications in person. These costs are high enough to impede the job search process of some workseekers (Kerr, 2017). Employment regulations in South Africa are unusually difficult to navigate, making legal disputes in hiring commonplace (Magruder, 2010; Rankin & Roberts, 2011). As a result, employers are often reluctant to hire someone without referrals or significant work experience. And South African schools assess student achievement inaccurately and inconsistently, which limits employers’ ability to use educational qualifications to differentiate between job candidates (Lam et al., 2011; Taylor et al., 2011).

South African unemployment by age and gender

Note: This figure is reproduced from page 4 of Mosomi and Wittenberg (2020). Mosomi and Wittenberg generated the figure using data from Post-Apartheid Labour Market Surveys (PALMS)

In this context, transitions into formal employment have been particularly difficult for young workseekers. South Africa currently has one of the highest rates of youth unemployment in the world, with more than 55% of South Africans aged 15–24 years not in employment, education, or training (Statistics SA, 2019). This is twice the unemployment rate of adults aged 25–64 in the same time period. Figure 12.1 shows that the youth-adult unemployment gap has been high and relatively stable for many years (Mosomi & Wittenberg, 2020). Furthermore, large numbers of young people in South Africa – particularly young men – have stopped searching for work altogether, likely due to discouragement resulting from persistent high unemployment.

Although youth unemployment is particularly stark in South Africa, young people in many parts of the world contend with high rates of unemployment, underemployment, and unstable employment (ILO, 2017). More than 70 million people between the ages of 15 and 24 are unemployed worldwide, representing a youth unemployment rate three times the adult unemployment rate (ILO, 2017). Young workseekers tend to have less formal education and on-the-job training than adults, which could suggest to prospective employers that they are less qualified. Youth with limited prior work experience may also be disadvantaged by their lack of references from past employers and the small size of their professional networks. As outlined in Fig. 12.2, these “frictions” that interfere with the hiring process could explain the disproportionately negative employment and earnings outcomes of young people.

Past research has established that pervasive youth unemployment has wide-ranging and long-lasting implications for out-of-work young people and for the countries where they live. Long unemployment spells in youth increase the probability of unemployment into adulthood and may have lasting effects on a range of other schooling and economic outcomes (Schmillen & Umkehrer, 2017; Mroz & Savage, 2006; Bell & Blanchflower, 2011). Research out of Europe suggests that, in the absence of early policy interventions, even short periods of high youth unemployment may become a regular feature of a country’s economy (Caporale & Gil-Alana, 2014). Entrenched youth unemployment is associated with economic instability, crime, and political unrest in many countries (Fougere et al., 2009; Okafor, 2011; Ajaegbu, 2012).

This case study describes how researchers adapted an existing technology to target the disconnect between young workseekers and employers in South Africa. While young people in South Africa experience particularly high rates of unemployment, they also demonstrate relatively high levels of digital proficiency (Pew Research Center, 2018), suggesting they may constitute a demographic likely to benefit from technological solutions to formal sector employment challenges. Researchers taught groups of young workseekers to use the world’s largest online professional networking platform, LinkedIn. In principle, there are many reasons why an online networking tool such as LinkedIn could increase employment in South Africa. The South African workforce ranks among the highest and most diversified digital skills of any developing country, and digital proficiency continues to improve with Internet infrastructure improvements (Choi et al., 2020). Workseekers can use the online platform to acquire information about job openings, to apply for jobs, or to elicit referrals from other users. At the same time, employers can use the platform to acquire information about applicants or to post job openings. Results of the evaluation suggest that training young workseekers to use LinkedIn speeds up their transition into formal employment.

Addressing the youth unemployment crisis is imperative to South Africa’s continued development as an economic leader in sub-Saharan Africa. Today, the nonprofit, private, and public sectors in South Africa each play a role in the removal of barriers to youth employment. The public sector has led the way, devoting myriad resources to aiding workers and employers in the job search process. Shortly after becoming a democracy in 1994, the Government of South Africa developed a multipronged strategy for improving young workseekers’ access to jobs, focusing on improving formal education and expanding vocational training opportunities, creating public employment programs, and funding job placement programs. Especially since the mid-2000s, skills and training programs have proliferated in a variety of forms throughout the country. One of the most high-profile initiatives targeted at employers is the Employment Tax Initiative (ETI), a wage subsidy launched by the South African government in 2014 that effectively reduces the cost of hiring young South African workseekers. Despite evidence that many of these interventions have had some success (e.g., Ebrahim et al., 2017), levels of youth unemployment remain high, which has spurred the growth of private and nonprofit solutions. This case study suggests an important role for software development in tackling the challenge of youth unemployment.

2 Project Formation

This case study details how an international team of researchers from Duke University and RTI International, in partnership with a local nonprofit organization and a leading professional networking service, set out to tackle the problem of youth unemployment in South Africa. Between 2015 and 2019, the project team adapted an existing technological solution to job search barriers, introduced the innovation to young South African workseekers, and conducted an evaluation to assess the effectiveness of the innovation. Specifically, the team studied whether the online digital professional networking platform, LinkedIn, could be used to improve the employment outcomes of young, economically disadvantaged workseekers in South Africa. The evaluation was a randomized control trial (RCT) that randomly assigned some job training cohorts to receive training on LinkedIn platform use. Wheeler et al. (2019) detail the results of the evaluation.Footnote 2 This section of the case study describes how the research team devised the study with several practical factors in mind, including the existence of a reliable implementation partner and high levels of digital connectivity in the South African population.

2.1 Tailoring a Solution to the Local Context

LinkedIn is a social media site built to facilitate professional networking and development. Users of the site create public profiles containing information about their skills, qualifications, and employment experience. Profiles may also include endorsements written by former supervisors or colleagues. Workseekers and prospective employers engage with LinkedIn in several ways that may help connect workseekers to jobs. To name a few, workseekers can use LinkedIn to learn about job openings, to form virtual professional networks by adding other users as connections, and to submit job applications costlessly online. Employers can use LinkedIn to advertise job openings and to screen applicants based on information contained in their LinkedIn profiles. Survey data suggest that both workers and firms commonly use LinkedIn to find jobs (Collmus et al., 2016). Hiring managers reportedly use LinkedIn at both the recruitment stage and the interview stage to fill in information gaps about workseekers (Caers & Castelyns, 2010; Roulin & Levashina, 2018). Other types of digital networking have been proven effective in connecting local employers, mostly in high-income contexts, to nonlocal contract workers, mostly in low-income contexts (Agrawal et al., 2015). But research into the effectiveness of digital technologies as employment solutions remains thin. The study conducted by the research team is the first to experimentally evaluate the employment effects of training workseekers to join and use an online professional networking platform.

More than 75% of LinkedIn users come from outside the United States, including more than 7 million users based in South Africa (LinkedIn, 2020). South Africa is LinkedIn’s largest market in Africa. But only approximately 20% of LinkedIn users in South Africa are between 18 and 24, reportedly due to the perception that professional networking platforms are geared toward workers with more experience (Barbarasa et al., 2017). The underrepresentation of the South African youth population on the platform may represent an opportunity for growth. Once they sign up to join LinkedIn, young people in low- and middle-income countries like South Africa engage with the platform more actively and add connections faster than their older counterparts. LinkedIn is widely used by South African firms as well.Footnote 3 Although LinkedIn may be particularly relevant for high-skilled positions in the labor market, firms in South Africa also actively use LinkedIn to recruit workseekers for the types of entry-level positions that most economically disadvantaged youth would occupy. Approximately 50% of positions advertised in South Africa are entry level.

Relative to other developing countries – especially other countries in sub-Saharan Africa – digital connectivity in South Africa is high. More than 50% of South Africans own a mobile device that can connect to the Internet and applications, and nearly 60% of the population is able to access the Internet by any means (Pew Research Center, 2018). Smartphone ownership among South Africans aged 18–29 is at least ten percentage points higher than the overall mean in South Africa. With the caveat that Internet access is not uniform across the entire South African youth population (Oyedemi, 2015), these statistics suggest that there may be scope to expand the use of digital professional networking platforms like LinkedIn within the population of unemployed South African youths.Footnote 4 At baseline, 89% of the participants in this case study reported having an account on at least one of the following social media platforms: Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, or Mxit.

2.2 Identifying a Local Partner

The Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator (Harambee) is perhaps one of the most well-known nonprofit organizations focused on helping young people find jobs in South Africa. Harambee provides job training and matching services to thousands of economically disadvantaged young workseekers in South Africa every year, and their organization continues to grow. As of 2018, they also operate in Kigali, Rwanda. Harambee offers several different training programs ranging in duration from 3 days to 8 weeks. The programs are designed to help workseekers acquire the skills needed to be successful in jobs in financial services, sales, logistics, and operations. At the end of some of the training programs for high performers, Harambee also arranges interviews between workseekers and prospective employers belonging to the network of firms Harambee has built over the years.Footnote 5 In its first 9 years of operation, more than 700,000 workseekers completed Harambee’s training programs, materializing into more than 160,000 jobs and work experiences with more than 500 employers.

Harambee admits workseekers aged 18–29 from low-income households with little to no work experience. Only a small minority possesses more than a high school education. The research team identified LinkedIn as a possible tool to overcome the specific set of constraints facing the workseekers participating in Harambee’s job training programs. For many of the reasons listed in the introduction, traditional job search strategies are often unsuccessful for this sample of workseekers. The young people eligible for Harambee’s services tend to be those who lack professional referrals, know relatively little about specific job vacancies, and struggle to afford job application costs and fees. Harambee job training participants belong to a demographic that may be particularly likely to see returns to nontraditional job search strategies. Among the top 20 firms with a history of interviewing and hiring Harambee workseekers, at least 12 had active job postings on LinkedIn for positions that require only high school education at the time of the intervention. Firms using LinkedIn to recruit for entry-level positions report high demand for many of the skills Harambee seeks to hone during their training programs, including sales, marketing, and soft skills (Barbarasa et al., 2017).

Participants in the research study included 1,638 Harambee “candidates” enrolled in 30 of Harambee’s “bridging programs” across South Africa. The research team was able to involve Harambee candidates in the study due to a long-standing partnership between Harambee and several of the scholars on the research team. Investments in relationships with implementation partners or government agencies are often important inputs into the research process. In this case, the success of the research project hinged on the opportunity to partner with Harambee. The research team capitalized on Harambee’s job readiness training model as well as on their experience with research.

Harambee attributes its success in large part to its reliance on research. The organization administers a series of longitudinal surveys to the workseekers who go through their training program, both at the start of the program, when the trainees are “candidates,” and years after the completion of the program, when they are “graduates.” With a data store of millions of psychometric and non-psychometric assessments as well as longer-term employment outcomes, Harambee draws on rich analytics to make adjustments to their training programs over time. In addition, Harambee has a history of partnering with researchers from academic institutions to evaluate the efficacy of various employment interventions. Due to past involvement in large-scale randomized experiments, Harambee possesses a great deal of institutional knowledge about how to conduct rigorous experimental research. With Harambee as a partner, the intervention would be led on the ground by those with an understanding of important elements of the research design. For instance, Harambee training managers understood the need to keep control and treatment cohorts uninformed of their treatment status, also known as blinding, to mitigate bias that may result from participants behaving differently or reporting their outcomes differently based on knowledge of being treated.

Perspectives on the Researcher-Implementation Partner Relationship

Patrick Shaw and Laurel Wheeler: “Developing a good relationship with implementation partners is essential. Without the perspective and experience of researchers in the project space, the study is limited to second-hand expertise. Edwin Lehoahoa, a Harambee manager in public/private partnerships and burgeoning South African researcher, was particularly integral to the success of the research project. Edwin helped lead the implementation of the study and provided invaluable insights at several stages of the project. Case in point, we consulted with Edwin on a weekly basis during the writing process for this case study.”

Edwin Lehoahoa: “Our journey towards making professional social networks more widely accessible and engaging depends on not only our ability to design them to attract the younger generation but our ability to break the data cost barrier. Being an organization that is demand-led, when Harambee was afforded the opportunity to learn about the linkages that platforms in general can create between workseekers and opportunity holders, we were thrilled. Especially the idea of learning how LinkedIn, a platform traditionally used as a networking platform by professionals and highly experienced individuals can be evolved in order to attract and link more marginalised entry level work seekers with opportunities that are less formal and require lower experience and qualification levels. Data is our biggest asset at Harambee and this study afforded us the ability to use some of the outcomes to shape our journey towards becoming a platform organization that promotes inclusion and drives social change at scale.”

Best practices for conducting research in developing countries point to the importance of relying on the knowledge and experience of local implementation partners. The most productive relationships are built on the foundation of mutual respect for the other party’s expertise.

To select the sample for the study, the research team relied on Harambee’s existing process of recruiting and vetting workseekers. Harambee provided their administrative data on workseeker characteristics, including the data from cognitive and noncognitive assessments administered during the onboarding process. After sample recruitment, Harambee’s 6- to 8-week job training programs for high-performing workseekers, known within the organization as “bridging programs,” constituted the perfect environment within which to randomly introduce a curriculum based on LinkedIn.

For the most part, the incentives of the research team aligned with the incentives of the organization. From Harambee’s perspective, the intervention would be low cost and potentially high reward. Time spent on the intervention would displace only 4 hours of the standard 6- to 8-week job training programs. Recruitment, screening, and other activities off of which the research study piggybacked were already taking place, thereby representing zero additional cost. The organization’s familiarity with research and randomized experimentation also minimized the cost of educating the job readiness trainers responsible for implementation. At the same time, Harambee was invested in learning the outcome of the research. As an organization devoted to understanding the youth unemployment crisis in South Africa, the results of the research could be invaluable in terms of the design of future training programs or in terms of advocacy work between Harambee and the government and private sectors.

2.3 Defining and Refining the Problem Boundary

The research team cemented their interest in studying digital networking technologies as solutions to youth unemployment when they answered a call for proposals issued by LinkedIn’s social impact sector. Before finalizing the research design, however, researchers iterated through multiple sets of research questions in the early phases of the project. The original proposal focused on the power of networking technology to elevate workseeker expectations and aspirations. The underlying theory was that young workseekers may hold inaccurate and pessimistic beliefs about their interconnectedness to prospective employers and other workers. The research team hypothesized that providing young workseekers with a visual mapping of their professional connections would improve their employment outcomes.

Ultimately, the set of research questions addressed by the intervention did not include questions related to data visualization. In practice, the research evolved largely with the team’s understanding of data availability. For reasons discussed in subsequent sections, LinkedIn did not provide the research team with access to all the data collected and maintained by their organization. While LinkedIn shared coarse measures of user network size, they did not share detailed data on the connections themselves. For example, the provided data would indicate that workseeker A had N LinkedIn connections 6 months after the Harambee training program, but not that workseeker A connected to workseeker B on date T. The lack of granularity in the networks data forced researchers to redefine the problem boundary. In addition to information about the number and type of network connections, LinkedIn shared data on account opening, profile completion, and search activity such as how often participants used LinkedIn to view and apply for jobs. These measures enabled the research team to assess whether introducing young workseekers to LinkedIn increases the probability of opening an account (the extensive margin) and increases account usage (the intensive margin).

Data limitations also precluded researchers from conducting an in-depth exploration into the ways in which employers engage with LinkedIn in hiring. Job search is a two-way street. Just as workseekers may use the platform to collect information about job openings and prospective employers, employers may use the platform to collect information about job candidates. LinkedIn provided data on the number of times a study participant’s LinkedIn profile was viewed in the final month of the Harambee training program; however, LinkedIn did not provide detailed data linking employer views to candidate profiles. To help contextualize and interpret the results of the evaluation and to fill in the gaps created by data availability, the research team administered a short end-of-evaluation survey to hiring managers affiliated with employers that regularly partner with Harambee.Footnote 6

The final problem boundary was also shaped by the backgrounds and incentives of the research team, made up of a combination of economists, education researchers, and data scientists. The consensus view was that the research design should allow for measurement of LinkedIn usage as well as short- and long-run employment outcomes. But the mix of researchers generated interest in a variety of causal mechanisms, ranging from economic channels (e.g., screening and signaling) to behavioral channels (e.g., aspirations and educational engagement). In other words, researchers were interested not only in evaluating whether the intervention improved employment outcomes but also in understanding why. As part of the brainstorming stage of the research design, the team sketched a simple theory of change graphic outlining some of the hypothesized channels through which LinkedIn could affect employment outcomes. That sketch, which is reproduced in Fig. 12.3, guided the research design by helping researchers identify a set of measurable outcomes that may be related to LinkedIn use.

The original theory of change groups mechanisms into five categories: labor market information, networks, signaling/screening, psychosocial change, and educational change. In terms of the labor market information channel, LinkedIn could provide workseekers with information about job vacancies. It could also act as a centralized database of industries and employers, improving workseekers’ understanding of how their particular skills and qualifications match up to opportunities. Establishing or expanding a professional network allows workseekers to connect with individuals in the workforce who may have information about available job opportunities. Professional networks may also prove to be important sources of referrals. LinkedIn could provide workseekers with improved technology to signal their ability to prospective employers who would then use this information to screen prospective hires. Traditional signals may be particularly weak for young people with limited work experience and educational attainment. Finally, LinkedIn use signaling may be responsible for different types of behavioral change, including educational investment and psychosocial change. In terms of educational investment, LinkedIn usage could either increase workseeker enthusiasm for the job readiness training program and increase their effort or lead to discouragement and decrease effort. In terms of self-beliefs, LinkedIn may alter a workseeker’s perception of his/her fit for certain jobs through exposure to role models, among other things. Through these mechanisms, LinkedIn may ultimately impact both the propensity to be employed and the quality of the match between the young person and a particular job.

At the start of the study, the research team was broadly interested in how workseekers and employers alike could utilize digital networking to overcome frictions in the job search process. The initial belief was that digital networking presents young workseekers with an opportunity to gain job search skills and learn about suitable job opportunities; it presents prospective employers with an opportunity to search online for suitable workers. By the time the research design was finalized, the focus had narrowed to a set of testable hypotheses shaped by the local context, the partnerships with Harambee and LinkedIn, data availability, and the composition of the research team.

3 Innovate, Implement, Iterate, Evaluate, and Adapt

3.1 Innovation

The act of finding a job has evolved vastly with the rise of technology. Throughout the mid-to-late twentieth century, the standard job search strategy involved handing out resumes in person or placing or answering print job ads. Respondents to the 1967 Current Population Survey (CPS) administered in the United States could select from five job search categories: checking with a public employment agency, checking with a private employment agency, checking with an employer directly, checking with friends or relatives, or placing or answering ads. In the early 1990s, “checking with the employer directly” was the modal search strategy, and “checking with private employment agencies” was the most successful (Bortnick & Ports, 1992).

As Internet access expanded, listings about open positions previously posted in the classified sections of local newspapers began to move online (e.g., CareerBuilder.com, Monster.com). This worked both ways, as workseekers were increasingly able to post resumes and have employers do the searching. By 1998, 15% of workseekers in the United States were using the Internet to search for jobs (Kuhn & Skuterud, 2000). As the online market became flooded with resumes, referrals and professional networking became increasingly important.Footnote 7 LinkedIn was founded in 2002 as a platform that could simultaneously provide information about job openings, serve as a form of professional credentialing, and expand job search networks. Since then, demand for online platforms such as LinkedIn has continued to grow with the proliferation of smartphone usage.

LinkedIn has become a staple in many parts of the world, particularly in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. But LinkedIn tends to have lower visibility among workseekers and employers searching within developing countries. In some regions of the developing world, more localized platforms serve a function similar to LinkedIn. For example, Rozee.pk provides digital professional networking services in Pakistan (https://www.rozee.pk/), Babajob in India (http://www.babajob.com/), Silatech in the Middle East and North Africa (https://silatech.org/), and Shortlist in Africa and India (https://www.shortlist.net/). LinkedIn therefore exists within an ecosystem of online networking platforms that cropped up in response to the evolution of job search strategies.

This research project involved three innovations based on the existing LinkedIn technology. First, promoting the use of LinkedIn within the South African market is an innovation in application. Survey evidence from OECD countries shows that workseekers use LinkedIn to learn about prospective employers (Sharone, 2017). In addition, firms in OECD countries report that they collect information about job applicants from online media (Stamper, 2010; Shepherd, 2013; Kluemper et al., 2016). But there existed little research into how workseekers and firms use LinkedIn in the South African context.

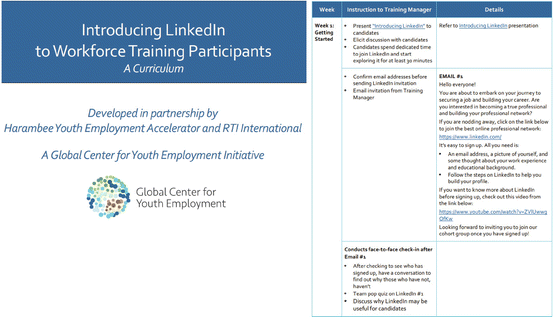

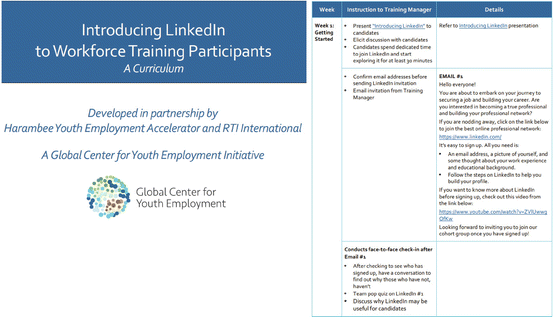

Second, the research team collaborated with LinkedIn and Harambee to develop a curriculum that would provide real access to this technology – not just getting users online and connected, but training them on how digital networking could help them gain employment. After co-developing the curriculum with a member of the Harambee staff, the team disseminated the LinkedIn training curriculum to Harambee job readiness trainers and taught them how to properly implement the LinkedIn training. The curriculum entailed a 1-hour presentation in the first week of the job training program plus additional coaching and discussion sessions in later weeks that covered building successful profiles, joining networks for targeted occupations, and on-platform searching for openings and companies. The curriculum is available in the paper’s supplementary materials from the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.Footnote 8 An example of the curriculum appears in the appendix.

The third innovation was to encourage the use of LinkedIn within an existing local learning environment. The rationale was that introducing the technology within an active job readiness training program with proven success would not only serve to augment digital literacy but also ensure sustainability. Other features contributing to sustainability of the technology include the stability of LinkedIn and the low cost of the intervention.Footnote 9

3.2 Design and Implementation

Before introducing the LinkedIn training curriculum to Harambee workseekers, the research team spent approximately one year designing the intervention. As depicted in Fig. 12.4, this was the first phase of many that would take place between 2015 and 2019. The evaluation was designed as a randomized control trial, relying on randomized treatment assignment to expose the causal relationship between LinkedIn and employment outcomes.

Researchers exploited much of Harambee’s preexisting infrastructure to streamline sample selection. As part of their regular process, Harambee recruits and screens workseekers and administers cognitive and noncognitive assessments during onboarding. These activities provided the sampling frame and data on population characteristics. Prior to randomization, the research team conducted a series of power calculations to determine how many workseekers would need to be included in the experiment. Using information about the average size of Harambee’s job readiness training programs, as well as other information about design features and parameter estimates from South African survey data, researchers decided to include 30 training cohorts in the study. To illustrate this process, a power calculation exercise appears at the end of this chapter. Next, researchers conducted pairwise randomization of Harambee’s next 30 job readiness training cohorts across its South Africa locations, effectively creating matched treatment-control pairs by location. All of these design decisions were logged and registered in the American Economic Association’s Randomized Control Trial (RCT) Registry before implementation.

In the second phase of the project, the research team gathered in South Africa to run a pilot study of the feasibility of the research design. As part of the pilot activities, the team devoted substantial time to writing and revising the survey instruments. Focus group interviews with Harambee job readiness training program participants helped refine survey questions and tailor the LinkedIn training curriculum to the sample population. Another outcome of the pilot was the development of a short informational session directed at job readiness trainers to improve their understanding about the experimental nature of the intervention.

Approximately one month after the pilot study, the main intervention kicked off with the start of a job readiness training cohort in Johannesburg assigned to the control group. Two days later, the second study cohort began their training in Cape Town. Scaling up from the pilot study was relatively seamless, in large part thanks to Harambee. Researchers positioned the intervention directly within Harambee’s existing training programs and used a portion of the job readiness training time to administer both the LinkedIn training and the baseline and endline surveys. AllHarambee training centers provide workseekers with access to computers that they otherwise may not have. Without free Internet access, some workseekers may have been unwilling or unable to sign up for and use LinkedIn. In addition, administering the surveys during the Harambee training program ensured high response rates without the need to offer cash incentives for completing surveys. This costless survey administration is in contrast to the 6-month and 12-month follow-up surveys, which were costly in terms of hiring the third-party professional survey firm as well as in terms of the airtime incentives provided to study participants to increase response rates.

Because Duke and RTI researchers were based in different parts of the world, Harambee played an important role in overseeing the day-to-day execution of the intervention. Harambee’s job readiness trainers administered the LinkedIn treatment. Each cohort was led by one job readiness trainer responsible for overseeing the entirety of the training for the 6–8-week program. Although some training cohorts included in the study did overlap temporally and geographically, participants of different training cohorts were kept largely separate, minimizing the opportunity for treatment spillovers. Trainers were familiarized with the LinkedIn training curriculum prior to the start of the intervention, but they were not notified of their cohort’s treatment status until the first day of each program. Study participants would never be made aware of their treatment status, and the only difference between control and treatment training programs would be the addition of the LinkedIn training curriculum in the treatment cohorts.

Between 2016 and 2018, while control and treatment training programs took place across Johannesburg, Pretoria, Cape Town, and Durban, the research team focused their energy on data collection, cleaning, and storage. The last training program included in the study concluded in early 2018, but data collection efforts did not conclude until one year later. The impact evaluation ultimately consisted of a sample of 1,638 workseekers from 30 different training programs across four South African locations. The project produced a longitudinal dataset that followed workseekers from the start of their training at Harambee to 12 months after the completion of their training program.

3.3 Implementation Challenges and Iterations

The partnership with Harambee enhanced implementation efficiency. Nonetheless, the intervention was not spared the occasional implementation challenge. The challenges can be grouped into three broad categories: treatment administration, survey administration, and general data collection and cleaning.

-

(a)

Treatment Administration

The intervention experienced several unanticipated lengthy delays between training programs. Harambee’s job readiness training programs included in the study had scheduled start dates ranging from May of 2016 to November of 2017. Many of these programs overlapped with holiday seasons, which impacted enrollment and survey response rates. At times, four different programs would start in a 3-week span, and then no program would start for months at a time. Toward the end of the study, the programs were delayed significantly due to lack of enrollment. The research team expected to complete the intervention by mid-2017 but in reality did not finish until early 2018.Footnote 10

In addition, a few technological glitches interfered with treatment administration at the individual level. During the LinkedIn training, some users were inadvertently locked out of their LinkedIn accounts. This issue, which affected five study cohorts, was resolved with assistance from LinkedIn. A robustness check treating the affected cohorts as “non-compliant” shows that the lockout issues did not meaningfully change the results of the study. The cause of the issue was never identified.

The research design ceded much of the control over implementation to the trainers responsible for running Harambee’s job readiness training programs. Early in the intervention, the research team learned the importance of instilling within these trainers a sense of accountability for the LinkedIn component of the training. One of the early training cohorts assigned to the treatment group did not receive the LinkedIn training because the trainer responsible for that cohort neglected to administer the curriculum. The research team was not able to oversee the implementation in person, and because the cohort was not based out of the main offices in Johannesburg, the research partners at Harambee were also unable to observe. Although the research team had built a strong relationship with Harambee as an organization, they had not at the onset built buy-in with each of the trainers nor implemented a trainer feedback system.

For the majority of the job readiness cohorts included in the intervention, implementation challenges were minimal. The research team informally received feedback from Harambee regarding points of confusion or difficulty for both the implementers and the workseekers. For example, an implementer from Johannesburg opined that “some of (the workseekers) hadn’t spent a lot of time on the platform because they were intimidated by the platform layout,” likely because they “didn’t know where to find things or where to begin.” The team addressed these concerns with updates to the LinkedIn training. As expected, implementer comfort with the curriculum progressed naturally throughout the study. The team also developed a short educational session for trainers, and Harambee further socialized them to the expectations of the project through one-on-one outreach. This alleviated many of the initial struggles for the program trainers.

-

(b)

Survey Administration

Survey implementation at scale is a large coordination effort. The study had a baseline survey administered in the first week of the program, an endline survey administered in the last week, and 6- and 12-month follow-up surveys administered after the end of the training. Researchers sought to collect data from each study participant to maximize the representativeness of survey responses, but some amount of nonresponse was unavoidable. The baseline survey missed study participants who were absent on the day of the survey or who enrolled late in the job readiness training program, the endline survey missed some participants who found employment before the end of the program or who left the program for other reasons, and the follow-up surveys missed participants who were not reachable by the survey firm after the training program, often due to changing phone numbers. Nonresponse was under 1% for the end-of-program employment measures, 32% in the 6-month surveys, and 40% in the 12-month surveys. Wheeler et al. (2022) show that nonresponse does not differ by treatment status and is only weakly related to the baseline characteristics of study participants.

Survey administration presented additional challenges that proved costly, from either a time or pecuniary standpoint. The research team invested countless hours in cleaning survey data. The web-based baseline and endline surveys required respondents to enter their own identifying information in open text questions. The identifying information, which facilitated the merging of data from different sources, often did not match across surveys due to data entry errors. To resolve the mismatches, selected members of the research team collected and cross-referenced multiple identifying pieces of information, including the respondents’ Harambee identification number, full name, date of birth, location, gender, and email address.Footnote 11 These data required an immense amount of cleaning. Furthermore, in some instances, study participants started the baseline survey, got kicked offline or inadvertently closed the window, and then started a new survey. Although rare, these responses showed up on the back end, forcing the research team to sift through duplicate responses as a regular part of the data cleaning process. The research team also invested time in coaching trainers on how to facilitate the web-based baseline and endline surveys. The research team explained when and how trainers could offer assistance without biasing responses. Finally, loss of power interrupted a few of the web-based surveys. Although not an unusual occurrence in South Africa, these power outages necessitated the readministration of some of the web-based surveys.

The follow-up survey administration proved extraordinarily costly from both a time and pecuniary standpoint. Because a companion study found low rates of response to both web- and SMS-based surveys in the same setting (Lau et al. 2018), the research team hired a professional survey firm to administer the follow-up surveys by telephone, which had a large impact on the budget. To maximize response rates, the survey firm called participants up to 30 times until successfully contacting them, which was both time-consuming and expensive. The call center averaged nine calls per respondent in the 6-month follow-up with 14% of respondents requiring 20 or more call attempts. Participants were even more difficult to reach at the 12-month follow-up, when the survey firm averaged twelve call attempts per respondent, with 24.5% of respondents requiring 20 or more call attempts. The final cost of the follow-up survey effort was US$93,000, which amounts to approximately US$30 per study participant per follow-up survey or US$44 per completed survey.

-

(c)

Other Data Collection and Cleaning

Data collection and cleaning challenges measured larger than any other implementation challenge. In addition to the baseline, endline, and follow-up surveys administered specifically for this research project, the evaluation relied on LinkedIn data and Harambee administrative and performance data. The data provided by these third-party sources presented standard challenges of data availability and data quality. At the research design phase, researchers did not know with certainty which measures would be provided by various sources, so some of the planned analysis was not feasible. In addition, the Harambee in-training performance measures that were prespecified as outcomes of interest in reality contained too many missing values to include in analysis.

Sourcing timely LinkedIn data proved to be one challenge to data collection. Delays were due in part to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which was introduced in the middle of the study. For a short period of time, LinkedIn paused data sharing as the organization ensured compliance with the new regulations. Researchers addressed this issue statistically to account for the possibility of both of time-varying data collection effects as well as time-invariant geography effects. LinkedIn data collection presented another challenge in the form of missing data. The data shared with researchers contained missing values for a small number of study participants who had LinkedIn accounts and should have been included in the dataset. The research team investigated the problem by manually cross-referencing the names of the study participants with the names and work experiences of LinkedIn users. According to LinkedIn, these active accounts were not found by automated scraping procedures due to the existence of different emails, misspellings or typing errors, or variations on given names.

Data issues persisted throughout the study, so it was necessary to iterate data collection methods as the study progressed to ensure data reliability and validity. The product of the data collection efforts was a large panel dataset that combined microdata from more than ten different sources and tracked study participants from the start of the intervention to 12 months post intervention. The final dataset contained web-based and phone-based survey data, LinkedIn data, and Harambee administrative data. Simply connecting all of these pieces was difficult, and the result required extensive cleaning.

A final set of data challenges arose as a byproduct of inter-institution collaboration. Different institutions impose different standards for data storage. In accordance with Internal Review Board (IRB) standards at different institutions, the research team kept two datasets: one containing identifying information and a random identifier for each subject and an anonymized dataset containing the random identifier plus all substantive information from the surveys. The two datasets were stored separately and hosted on a cloud-based storage service that can be encrypted. No identifiable individual-level data was shared with Harambee or any other organization. In compliance with data sharing agreements between RTI and LinkedIn, no LinkedIn data was given to Duke researchers or stored on Duke servers.

3.4 Evaluation

The evaluation compared the experiences of study participants exposed to the LinkedIn training (the “treated” participants) to the experiences of study participants not exposed (the “control” participants). The research team discovered that, at the end of Harambee’s job readiness training program, treated participants were 10% more likely to find immediate employment than control participants. Higher levels of employment persisted for at least 12 months following the intervention. Furthermore, treatment-control differences in employment appear to be driven by treatment-control differences in LinkedIn use. The research team found that exposure to the LinkedIn training increased the probability that a participant had an active LinkedIn account and also increased the intensity with which the participant engaged with LinkedIn. The results suggest that, at least in this specific context, training young workseekers to use LinkedIn speeds up their transition into employment.

Because the intervention was designed to be a solution to the challenge of youth unemployment in South Africa, researchers identified short-run and long-run employment as the primary outcomes of interest. Harambee provided a measure of short-run employment, a binary indicator of whether the study participant was employed immediately out of the job readiness training program. The research team administered surveys to collect data on longer-run employment 6 and 12 months post training. In addition to the binary employment information, the surveys solicited information about the quality of the worker-job match, measured by job retention, promotion, and permanency. In practice, researchers found little evidence of treatment impacting match quality.

Treatment-control differences in current employment suggest that something about the intervention was responsible for improving employment outcomes. In order to attribute those differences to LinkedIn use, the team analyzed whether and how study participants engaged with the LinkedIn platform. Extensive margin measures of LinkedIn use – such as whether study participants opened an account during the intervention – were examined alongside intensive margin measures of LinkedIn use, such as profile completion, number of profiles viewed, number and types of connections made, and number of job applications submitted through the platform. LinkedIn provided these measures at three points in time, roughly corresponding to the end of the training program and 6 and 12 months post training. LinkedIn designed their own tools for tracking user behavior and sent the research team the usage variables they had already constructed. In addition to using LinkedIn-constructed measures, researchers employed statistical techniques to devise alternative measures of LinkedIn usage. For instance, researchers used the first principal component of a set of intensive and extensive margin measures to reflect an aggregate measure of LinkedIn use. The research team found evidence of compliance with treatment, based on the majority of these measures. The LinkedIn treatment increased LinkedIn use both by encouraging study participants to open accounts and by increasing the intensity with which they engaged with their accounts.

Researchers designed the evaluation to include a host of other measures that would be used to shed light on the role of the hypothesized mechanisms laid out in the original theory of change (see Fig. 12.3). In terms of information provision, researchers found that treatment significantly increased the number of profiles viewed and the number of jobs viewed on the LinkedIn platform, suggesting that study participants may have used the platform to acquire information. The average number of profile and job views was nevertheless quite low. LinkedIn provided researchers with a measure of the number of articles read on the platform, but the vast majority of participants read zero articles.

In terms of network formation, LinkedIn provided the research team with four different variables describing a study participant’s professional network on the platform: number of connections, number of connections with a bachelor’s degree, number of connections in a managerial position, and the average power of connections.Footnote 12 Treatment had a positive impact on all network measures. LinkedIn measures did not include information about the ways in which participants interacted with their connections or about the identities of the network connections.

Treated participants were significantly more likely to have complete LinkedIn profiles, suggesting a role for the signaling of workseeker ability. Although the research design did not provide researchers with the opportunity to observe the ways in which employers used and interpreted LinkedIn profiles, several measured changes are consistent with the signaling/screening channel. First, researchers observe that the treatment employment rate rises by the end of the job readiness program, suggesting a quick mechanism like LinkedIn profiles helping workseekers pass employer screening. Second, treatment almost triples the number of times a workseeker’s profile is viewed by other LinkedIn users in the month of program completion. This may reflect prospective employers viewing profiles during hiring. However, limited information from the short firm survey conducted ex post suggests that this mechanism likely was not important in determining the results. None of the hiring managers who responded to the survey reported that they viewed LinkedIn profiles during hiring.

Finally, to measure change in educational investment, researchers collected self-reported measures of interest in the job training program and studied job readiness trainer reports describing things like participant energy and intellectual curiosity. Treatment did not have an impact on these measures. To test the psychosocial channel, researchers included in their survey instruments questions about study participants’ expectations and aspirations. Similarly, treatment had almost no impact on these measures. Although researchers only measured a subset of the possible types of self-belief, they found no evidence to suggest that the LinkedIn training impacted employment through its impact on behavioral change.

The research was not designed to test mechanisms directly but rather to provide suggestive evidence on the channels through which the LinkedIn training may affect the main outcome of interest: employment. The evaluation shows that LinkedIn training was responsible for increasing post-program employment from 70% among control participants to 77% among treated participants. This 10% increase is comparable to the average effect of other active labor market interventions targeted toward long-term unemployed workseekers (Card et al., 2017). While recognizing that this intervention took place within a unique context, a case may be made for adopting similar technologies to solve youth unemployment challenges in other countries. This is particularly true in light of the high benefit-to-cost ratio associated with the intervention. The research team calculated that the cost of the intervention totaled approximately US$48 per study participant.Footnote 13 That is relative to the treatment-induced increase in earnings of approximately US$417 over the course of 1 year. Cost-benefit calculations are given by the exercise at the end of the chapter.

3.5 Adaptation

Based on the benefit-to-cost ratio alone, a case may be made for exploring the use of LinkedIn training in other countries. High youth unemployment is an issue that affects many developing countries, in particular countries in the Middle East and North Africa. But there are a few unique features of the study context that may limit generalizability. First, the study participants were disadvantaged but high achieving, suggesting higher-than-average technological familiarity for their demographic. Second, South Africa has high rates of LinkedIn use by workseekers and employers. Without a strong LinkedIn presence in a country, take-up would be low. Third, this case study describes an intervention that takes place within an existing job readiness training program. In the absence of an organization like Harambee, it is unclear whether the LinkedIn curriculum would be effective.

Scaling up from this intervention more broadly even throughout South Africa requires some consideration of the obstacles to digital networking. Platform accessibility and inclusivity are imperative for widespread take-up of digital networking tools. More than nine in ten Harambee workseekers use Internet-enabled phones (though not necessarily smartphones), but South Africa has some of the highest data costs in the Southern African Development Community. Thus, lowering costs through subsidies or incentives or expanding free public Internet access would be a big step in scaling. An additional option, which Facebook has recently tested, provides a stripped down application version available at little to no data cost and allows youth from marginalized communities and those without smartphones to engage with the network. This also provides an opportunity for marginalized young people to have a voice in the development of these types of innovations.

Another aspect of scalability pertains to the quality of other operators in the employment ecosystem. Harambee has found success in its workflow model, but the organization cannot reach every individual that needs training and support. The structure of the LinkedIn intervention can be easily replicated in a similar “facilitating” environment and in other sectors. Existing vocational training and job readiness programs across sub-Saharan Africa do not necessarily simulate Harambee’s environment.

4 Lessons Learned

Five years after devising a research question about whether LinkedIn could increase youth employment in South Africa, the research team has produced the first experimental evidence that training participants in a job readiness training program to use an online professional networking platform improves employment outcomes. The LinkedIn training curriculum increased immediate employment by 10%, an effect that persisted for at least a year after job readiness training. The research team estimates that higher rates of employment among participants who received the LinkedIn training were largely driven by enhanced LinkedIn use.

Given the fairly distinct characteristics of the study population and employment context, these findings suggest several potential avenues for future research. Are there specific aspects of digital networking that drive the employment results? Can these tools be scaled or used at all outside of the job readiness environment? Would digital networking be as effective in a different country or with a different population of workseekers?

Even if the findings of the evaluation apply only to the employment conditions of a specific population, the lessons learned from the research project are wide reaching, including lessons about policy design, lessons about study implementation, and lessons about future technology design. Policy recommendations are rather straightforward, such as reducing data costs and encouraging the use of digital networking platforms in vocational and other job training programs. These insights into policy design have already informed Harambee’s advocacy with the government and private sectors. The results of the research study have strengthened Harambee’s call for a reduction in data costs to enable young people to access digital professional platforms.

In terms of study implementation, the research project underscored the importance of investing in redundant backup strategies to account for losses in Internet or power, such as laptops or tablets that can be used offline for training content delivery and survey data collection. In addition, for researchers working with a remote implementation partner, careful monitoring for fidelity of implementation, at least toward the beginning of the study, may alleviate some of the issues this research team experienced in delivering the intervention.

Finally, for future developers of digital job platforms, this research suggests a need for strategies to generate greater take-up. For populations that are economically disadvantaged, digital platform developers can design applications with low data demands. For populations that are not technology savvy, digital platform developers can build supportive curricula and training materials into their platforms, to help users onboard and interact with the platform in a deeper way.

Notes

- 1.

According to Statistics South Africa (2019), the informal sector comprises only 20% of total nonagricultural employment in South Africa.

- 2.

Since the time of writing, the paper has been published in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. It can be located using the following citation: Wheeler et al. (2022). LinkedIn(to) Job Opportunities: Experimental Evidence from Job Readiness Training. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14(2), 101–25.

- 3.

There were more than 250,000 active job postings on the LinkedIn platform at the end of the intervention.

- 4.

A study of students at a South African university found that students were online for 16 hours of the day (Uys et al., 2012). Only a small minority of the participants in the case study have a college degree, suggesting that the samples are not entirely comparable. Income inequality is one factor that seems to determine inequality in Internet access. Individuals living in rural South African communities may be significantly less likely to have and use a smartphone than those in urban areas (Dalvit et al., 2014).

- 5.

Although workseekers eligible for Harambee’s services tend to face less promising job prospects than the average South African workseeker, the individuals invited to join the “bridging programs” are those receiving the highest scores on the cognitive, communication, and numeracy assessments administered by Harambee.

- 6.

The survey elicited responses from the human resources staff at three large firms that jointly employ 20% of the study participants. None of the hiring managers reported using LinkedIn in hiring.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

Cost-benefit calculations are given by the exercise at the end of the chapter.

- 10.

In analysis, researchers control for timing to minimize the impact of delays and seasonality on estimates of treatment effects.

- 11.

The Duke researchers did not have IRB permission to access the identifying information of the study participants. RTI researchers collected those data and anonymized the data before sharing with Duke researchers.

- 12.

The average power of connections is calculated by LinkedIn based on the number of connections as well as the education and skills of connections. It is a measure of network quality that is constructed by LinkedIn.

- 13.

The estimated cost is US$48 using purchasing power parity adjustments but US$21 at the nominal exchange rate.

- 14.

Note that these parameters and calculations are based on the design factors specific to the study at hand. They differ across studies based on differences in terms of the number of treatment arms, the level of randomization, the degree of compliance, etc. For more information, Duflo, Gennerster, and Kremer (2007) provide an excellent treatment on the principles of power calculations.

- 15.

Note that it’s best to use a range of estimates. Point estimates are given here for the sake of clarity.

References

Agrawal, A., Horton, J., Lacetera, N., & Lyons, E. (2015). Digitization and the contract labor market: A research agenda. In A. Goldfarb, S. Greenstein, & C. Tucker (Eds.), Economic analysis of the digital economy (pp. 219–250). University of Chicago Press.

Ajaegbu, O. O. (2012). Rising youth unemployment and violent crime in Nigeria. American Journal of Social Issues & Humanities, 2(5), 315–321.

Banerjee, A., et al. (2008). Why has unemployment risen in the new South Africa? The Economics of Transition, 16(4), 715–740.

Barbarasa, E., Barrett, J., & Goldin, N. (2017). Skills gap or signaling gap?: insights from LinkedIn in emerging markets of Brazil, India, Indonesia, and South Africa Solutions for Youth Employment, Washington D.C. LinkedIn.

Bell, D. N. F., & Blanchflower, D. G. (2011). Youth unemployment in Europe and the United States. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5873, April 2011

Bortnick, S. M., & Ports, M. H. (1992). Job search methods and results: Tracking the unemployed, 1991. Monthly Labor Review, 115(12), 29.

Caers, R., & Castelyns, V. (2010). LinkedIn and Facebook in Belgium: The influences and biases of social network sites in recruitment and selection procedures. Social Science Computer Review, 29(4), 437–448.

Caporale, G. M., & Gil-Alana, L. (2014). Youth unemployment in Europe: Persistence and macroeconomic determinants. Comparative Economic Studies, 56, 581–591.

Card, D., Kluve, J., & Weber, A. (2017). What works? A meta analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations. Journal of the European Economic Association, 16, 894–931.

Choi J, Dutz M A, Usman Z (2020) The future of work in Africa: Harnessing the potential of digital technologies for all.. The World Bank Group

Collmus, A. B., Armstrong, M. B., & Landers, R. N. (2016). Game-thinking within social media to recruit and select job candidates. Social media in employee selection and recruitment: Theory, practice, and current challenges, 103–124.

Dalvit, L., Kromberg, S., Miya, M. (2014). The data divide in a South African rural community: A survey of mobile phone use in Keiskammahoek. Proceedings of the e-Skills for Knowledge Production and Innovation Conference 2014, Cape Town, South Africa: 87-100

Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., Kremer, M. (2007). Using randomization in development economics research: A toolkit. CEPR Discussion Paper No. 6059

Ebrahim, A., Leibbrandt, M., Ranchhod, V. (2017). The effects of the Employment Tax Incentive on South African employment. WIDER Working Paper 2017/5

Fougere, D., Kramarz, F., & Pouget, J. (2009). Youth unemployment and crime in France. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(5), 909–938.

International Labour Organization. (2017). Global employment trends for youth 2017: Paths to a better working future. International Labour Office.

International Labour Organization. (2018). Women and men in the informal economy: A statistical picture. International Labour Office.

Kerr, A. (2017). Tax(i)ing the poor? Commuting costs in South African cities. South African Journal of Economics, 85, 321–340.

Kingdon, G., Knight, J. (2001). Why high open unemployment and small informal sector in South Africa? Centre for the Study of African Economies, Economics Department, University of Oxford.

Kluemper, D., Mitra, A., & Wang, S. (2016). Social media use in HRM. In Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 153–207). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Kuhn, P., Mansour, H. (2011). Is Internet job search still ineffective? IZA Discussion Paper No. 5955

Kuhn, P., & Skuterud, M. (2000). Job search methods: Internet versus traditional. Monthly Labor Review, 3, 3–11.

Kuhn, P., & Skuterud, M. (2004). Internet job search and unemployment durations. American Economic Review, 94(1), 218–232.

Lam, D., Ardington, C., & Leibbrandt, M. (2011). Schooling as a lottery: Racial differences in school advancement in urban South Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 95, 121–136.

Lau, C. Q., Johnson, E., Amaya, A., LeBaron, P., & Sanders, H. (2018). High stakes, low resources: what mode(s) should youth employment training programs use to track alumni? Evidence from South Africa. Journal of International Development, 30(7), 1166–1185.

LinkedIn. (2020). The LinkedIn register. https://news.linkedin.com/about-us#1. Accessed 12 August 2020

Magruder, J. (2010). Intergenerational networks, unemployment, and persistent inequality. South Africa American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2, 62–85.

Mosomi, J., & Wittenberg, M. (2020). The labor market in South Africa, 2000–2017. IZA World of Labor, 2020, 475.

Mroz, T., & Savage, T. H. (2006). The long-term effects of youth unemployment. Journal of Human Resources, XLI(2), 259–293.

Okafor, E. E. (2011). Youth unemployment and implications for stability of democracy in Nigeria. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 13(1).

Oyedemi, T. (2015). Participation, citizenship and internet use among South African youth. Telematics and Informatics, 32(1), 11–22.

Pew Research Center. (2018). Internet connectivity seen as having positive impact on life in sub-Saharan Africa

Rankin, N., & Roberts, G. (2011). Youth unemployment, firm size and reservation wages in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics, 79, 128–145.

Roulin, N., & Levashina, J. (2018). LinkedIn as a new selection method: Psychometric properties and assessment approach. Personnel Psychology, 72(2), 187–211.

Schmillen, A., & Umkehrer, M. (2017). The scars of youth: Effects of early-career unemployment on future unemployment experience. International Labour Review, 156(3-4), 465–494.

Sharone, O. (2017). LinkedIn or LinkedOut? How social networking sites are reshaping the labor market. In Emerging conceptions of work, management, and the labor market. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Shepherd, B. (2013). Social recruiting: Referrals. Workforce Management, 5(18).

Stamper, C. (2010). Common mistakes companies make using social media tools in recruiting efforts. CMA Management, 12, 13–22.

Statistics South Africa. (2019). Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS), 1st quarter 2019. Statistics South Africa.

Taylor, S., Van Der Berg, S., Reddy, V., Janse Van Rensburg, D. (2011). How well do South African schools convert grade 8 achievement into matric outcomes? Tech. Rep. 13/11, Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers

Uys, W., et al. (2012). Smartphone application usage amongst students at a South African university. IST-Africa 2012 Conference Proceedings: 1–11

Wheeler, L.E., et al. (2019). LinkedIn(to) job opportunities: Experimental evidence from job readiness training. University of Alberta Working Paper No. 2019-14

Wheeler, L.E., et al. (2022). LinkedIn(to) Job Opportunities: Experimental Evidence from Job Readiness Training. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14(2), 101–25.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

-

(i)

LinkedIn Training Curriculum

This image depicts the first part of the LinkedIn training curriculum administered by job readiness training managers. The full curriculum is accessible with the published version of the paper from the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics sited at https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20200025.

-

(ii)

Power Calculation Exercise

For most randomized evaluations, power calculations are an important step in the research design. Researchers design their experiments such that they are powered to detect post-intervention differences between control and treated participants. The power of the research design is the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis that treatment does not change outcomes when the null hypothesis is in reality false. One concern is that, if effect sizes are small, researchers may be underpowered to detect them and will fail to reject the null hypothesis when in reality the intervention was responsible for small changes in outcomes.

At the beginning of the intervention, researchers must consider trade-offs between the sample size they’ll use in their study and the minimum effect size they want to be able to detect, known as the minimum detectable effect size (MDE). As they increase the sample size, they decrease the MDE. In other words, with more data, the researchers are able to detect increasingly small responses to treatment. In reality, time and resources are limited, and the study sample cannot include the entire population of interest. This is where power calculations come into play.

Let’s illustrate the basic principles of power calculations by setting the parameters and calculating the minimum detectable effect size.Footnote 14 The relationship between the MDE and the design parameters is given by Eqs. (12.1) and (12.2), with the parameters defined below:

The relevant parameters include the following:

-

1.

Test size critical value ( t α/2 ): The value of this parameter is obtained from a standard t distribution. The researcher selects a significance level α and uses a t-table to identify the critical value associated with a two-sided test:

-

(a)

Assume: The level of statistical significance you aim to achieve is 5%

-

(b)

Question: What is the value of t α/2?

-

(c)

Solution: t α/2 = 1.96.

-

(a)

-

2.

Test power critical value ( t (1 − κ) ): The value of this parameter is also given by a t-table based on the level of power specified by the researcher:

-

(a)

Given: Researchers are typically satisfied with power of 80%.

-

(b)

Question: What is the value of t (1 − κ)?

-

(c)

Solution: t (1 − κ) = 0.84.

-

(a)

-

3.

Number of clusters ( J ): This study involved randomization of training groups rather than individuals, and treatment was administered at the group level. The number of clusters reflects the number of training groups. The researcher will solve for the number of clusters needed to obtain a large enough sample size for a given MDE:

-

(a)

Question: Does the MDE increase or decrease as the number of clusters increases?

-

(b)

Solution: The MDE decreases as the number of clusters increases, corresponding to an improvement in the study’s power.

-

(a)

-

4.

Number of units within each cluster ( n ): The number of units within each cluster reflects the expected number of individuals within each training group:

-

(a)

Assume: The number of units within each cluster is identical

-

(b)

Question: Does the MDE increase or decrease as the number of units within each cluster increases?

-

(c)

Solution: The MDE decreases. Again, increasing the overall sample size improves the power of the study (decreases the MDE).

-

5.

Intracluster correlation coefficient ( ρ ): This parameter accounts for the correlation of outcomes within groups. The intracluster correlation coefficient is the share of variance explained by within group variance. Estimates of ρ could come from pilot data or from national surveys of representative samples:

-

(a)

Given: Based on data on the baseline characteristics of the first few groups in the study, researchers estimate ρ =0.0165.Footnote 15

-

(b)

Tip: For any nonzero ρ, increasing J improves precision more than increasing n.

-

(a)

-

6.

Fraction treated ( P ): As part of the research design, the researcher determines the fraction of the sample that receives treatment. Unless the treatment is expensive, it is generally optimal to treat half the sample because P =0.5 minimizes the MDE:

-

(a)

Given: P =0.5.

-

(a)

-

7.

Number of posttreatment measures ( M ): Some outcomes are measured at multiple points in time after the intervention. This parameter is determined by the research design:

-

(a)

Given: The researchers plan to measure the outcome of interest at 6 months and 12 months post-intervention, so M = 2.

-

(b)

Question: How does the number of posttreatment measures affect the power of the study?

-

(c)

Solution: The number of posttreatment measures factors into the residual variation. Increasing M decreases residual variation, which increases the power of the study.

-

(a)

-

8.

Intertemporal correlation coefficient ( τ ): This parameter accounts for the correlation of outcomes over time. It is the share of the variance explained by variance over time. This parameter only becomes important if outcomes are measured at multiple points in time. Estimates of τ often come from longitudinal surveys of representative samples:

-

(a)

Given: Based on multiple waves of data from that National Income Dynamics Study, researchers estimate that τ = 0.312.

-

(a)

-

9.

Residual variation ( σ 2 ): This parameter is calculated based on the values of τ and M in a relationship given by Eq. (12.2):

-

(a)

Question: What is the value of σ 2 based on the information given in this example?

-

(b)

Solution: σ 2 = 0.656.

-

(c)

Question: Does the MDE increase or decrease with σ 2?

-

(d)

Solution: The MDE increases with σ 2, indicating that decreasing the residual variation improves the study’s power.

-

(a)

-

Putting it all together:

-

Question (1): Given the above parameter values, what is the minimum detectable effect size associated with 30 groups of 70 participants per group?

-

Question (2): Interpret this.

-

Question (3): How do you think researchers would determine if that’s an acceptable MDE for the study?

-

Solution (1): 0.1447.

-

Solution (2): Given the above parameter values, a sample of 2,100 study participants evenly divided into 30 groups would allow researchers to reject the null hypothesis with statistical certainty only if the treatment effect is greater than 0.1447.

-