Abstract

This contribution examines the evolution of public support for the euro since its introduction as a virtual currency in 1999, using a unique set of data not available for any other currency. We focus on the role of economic factors in determining the popularity of the euro. We find that a majority of citizens support the euro in each individual member country of the euro area (EA). The economic crisis in the EA provoked by the Great Recession led to a slight decline in public support, but the recent economic recovery has strengthened that support, which is now approaching historically high levels after two decades of existence. A similar, but less pronounced upturn in trust in the ECB can also be detected during the recovery. Our econometric work demonstrates that unemployment is a key driver of support behind the euro. Given these developments, we discuss whether the large and persistent majority support enjoyed by the euro equips the currency to weather populist challenges during its third decade.

Originally published in: Juan Castañeda, Alessandro Roselli and Geoffrey Wood (eds.). The Economics of Monetary Unions. Past Experiences and the Eurozone. Routledge, New York, NY, 2020, pp. 141–155.

The authors gratefully acknowledge constructive comments received from participants at the conference ‘The Economics of Monetary Unions: Past Experience and the Eurozone’ at the University Buckingham, and from Fredrik N.G. Andersson, David Laidler, Felicitas Nowak-Lehmann D, Thomas Straubhaar and Joakim Westerlund.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Key words

1 Introduction

The euro, the common European currency adopted in 1999, is now entering its third decade. The euro is unique in at least two ways. First, a large number of independent countries, EU member states, have handed over responsibility for their monetary policy to an independent central bank, the European Central Bank (ECB), while maintaining domestic control over fiscal policy. Second, the euro, to the best of our knowledge, is the only currency for which we have a long and consistent time series showing public support for the currency and public trust in the central bank that supplies the currency. No such opinion poll data exist for the dollar, the pound, or any other currency for that matter. This unique data set enables us to conduct innovative studies of the determinants of support for a currency actively in circulation.

The purpose of this contribution is to examine how the European public has viewed the euro throughout its first two decades. It also examines how trust in the ECB and in national governments has evolved among the EU member states within the euro area (EA) and those outside. We stress that we are looking at support for the euro and its governance from the perspective of the public as revealed in public opinion polls, which is not the typical approach adopted by economists. The latter tend to study currencies via other analytical methods, such as the optimum currency area (OCA) approach developed by Robert Mundell (1961) or the process of divergence and convergence within a monetary union. Our approach should be viewed as a complementary strategy to these more conventional ways.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the role of public support for the sustainability of a common currency within a monetary union. Section 3 summarises previous empirical findings. Section 4 describes the Eurobarometer data used in this study. Section 5 offers a descriptive summary of the measures used to quantify popular support and trust. Section 6 presents our macro-econometric findings. Section 7 explains the divergence in support for the euro and trust in the ECB. Section 8 offers an outlook on the future of the euro area. Section 9 concludes.

2 The Role of Public Support for the Euro

The literature on monetary unions and monetary unification identifies public support for a common currency as a key determinant of its long-term prospects for survival.

First, the literature on the history of monetary unions suggests that these entities depend on public support for their legitimacy and viability. As long as the common currency enjoys sufficient support, policymakers are able to make adjustments and adequately confront the challenges posed by political, economic, and financial disturbances and crises (Bordo & Jonung, 2000, 2003). According to Bordo and Jonung, the standard OCA criteria are too static to use as a means of evaluating the performance of a monetary union. They stress that ultimately it is the presence of strong political will that holds a monetary union together. An established political bond between European policymakers and their publics/voters guarantees flexible solutions to emerging challenges (Bordo & Jonung, 2003). Strong public support for the common currency may thus act as a shield deflecting the critical rhetoric voiced by populist parties on both the right and the left.

Second, the literature on the political economy of monetary unions based on the OCA approach highlights the concept of commonality of destiny. Echoing the literature on the history of monetary unions, Baldwin and Wyplosz (2019) argue that it is foremost this political OCA criterion that accounts for the survival of the euro. The sense of a shared common destiny helps policymakers to find solutions in difficult times. Such a feeling is of key importance for reconciling the conflicting interests of the EA governments, which represent a significant source of the recent crisis in the EA (Frieden & Walter, 2017).

Third, political scientists stress that public support for the euro is crucial for any potential move towards deeper supranational governance (Banducci et al., 2003). In general, broad public support for the euro is viewed as a necessary pre-condition before European citizens will entertain a further transfer of power from national to European institutions (Kaltenthaler & Anderson, 2001). The political science literature concludes that public support is central to the political legitimacy and thus sustainability of the euro as well (Deroose et al., 2007; Verdun, 2016).

Public support alone, however, is not sufficient in itself to ensure the long-term survival of the euro. Trust on the part of the public in the institutions responsible for governing the euro is also crucial in this context. For this reason, we look at two measures of trust: trust in the ECB and trust in the national government.

3 Earlier Studies

Empirical studies analysing public support for the euro can roughly be clustered into one of the four groups:

-

1.

Studies of public support for a common currency in the years before the introduction of the euro, that is from 1990 until 1999, e.g. Kaltenthaler and Anderson (2001) and Banducci et al. (2003);

-

2.

Analyses of public support for the euro in the pre-crisis period from 1999 to 2008, such as Banducci et al. (2009) and Deroose et al. (2007);

-

3.

Contributions dealing with the crisis phase from 2008 to 2013, including Hobolt and Leblond (2014), Hobolt and Wratil (2015), and Roth et al. (2016); and

-

4.

Recent papers focusing on the impact of the recovery from the crisis from 2013 onwards, for example Roth et al. (2019).

What can we learn from this body of empirical work? For the sake of brevity, we focus on papers published since the introduction of the euro in 1999.

Looking at descriptive statistics, we find mixed evidence concerning majority support for the euro in the individual countries of the EA. Although Roth et al. (2016) show majority support for the euro since its establishment in 1999 in each individual country, Guiso et al. (2016) and Stiglitz (2016) claim that only a minority of citizens supported the currency in Italy and Germany. A study by Roth et al. (2019) argues that this discrepancy is due to the fact that Guiso et al. (2016) and Stiglitz (2016) use opinion poll data, which do not stem from data produced by the Eurobarometer surveys. The latter, to date, are the sole authoritative source of data for measuring public support for the euro across countries and over time.

An examination of the macro-evidence adduced in the literature reveals that the impact of unemployment and inflation on public support for the euro is a controversial question. While Hobolt and Leblond (2014) find no significant relationship between unemployment and net support for the euro, Roth et al. (2016, 2019) establish a weak negative relationship during the crisis but a stronger impact during the post-crisis recovery.

A similarly controversial finding applies to the effect of inflation on public support. While Banducci et al. (2003) and Hobolt and Leblond (2014) rule out a significant relationship between inflation and net support for the euro in pre-crisis and crisis years, Roth et al. (2016, 2019), who rely on an econometric analysis for 1999–2017, find a strong negative coefficient between an increase in inflation and a decline in net support for the euro before and during the crisis. This effect dissipates during the economic recovery.

Micro-data give support to the findings based on macro-data. Analysing a micro-dataset with 474,712 observations over the time period 1999–2017 for an EA19 country sample, Roth et al. (2019) find that perceptions of inflation and unemployment yield negative coefficients, whereas perceptions of the economic situation yield a positive coefficient. The findings concerning socioeconomic variables, such as gender, education, and employment status in the pre-crisis period, are similar to the results previously reported by Banducci et al. (2009). The latter find a stable pattern for education, employment, and legal status when comparing the pre-crisis period with the crisis-recovery period. In addition, Roth et al. (2019) detect a halving of the negative female coefficient and report a complete reversal in opinion among the oldest age group (65+) when comparing the pre-crisis with the crisis-recovery period. They conclude that the largest effect on public support for the euro is related to education.

Concerning public support for the euro and trust in the ECB, some first results have been published by Roth (2015), who highlights the contrasting evolution of public support for the euro and trust in the ECB. In addition, Roth et al. (2016) compare the effect of the unemployment crisis on public support for the euro with the effect on trust in the ECB. Here an increase in unemployment is roughly four times more negatively associated with trust in the ECB than in public support for the euro.

To sum up, research on the determinants of support for the euro is evolving. We would expect this to be the case as the new currency is only 20 years old. In addition, the euro area has recently experienced a major crisis and is still in recovery.

4 Eurobarometer Data

Our measures of public support for the euro are based upon the biannual Standard Eurobarometer (EB) surveys (European Commission, 2018) from March–April 1999 (EB51) to November 2018 (EB90). These surveys ask a representative group of respondents the following question: ‘What is your opinion on each of the following statements? Please tell me for each statement, whether you are for it or against it. A European economic and monetary union with one single currency, the euro’. Respondents can then choose between ‘For’, ‘Against’, ‘Don’t Know’ or (since Eurobarometer 90) ‘Spontaneous Refusal’.

Measures for trust in the ECB are based on responses to the following question: ‘Please tell me if you tend to trust or tend not to trust these European institutions. The European Central Bank’. Respondents can then choose between ‘Tend to trust’, ‘Tend not to trust’ or ‘Don’t Know’.

Measures for trust in the national government are based on responses to the following question: ‘I would like to ask you a question about how much trust you have in certain media and institutions. For each of the following media and institutions, please tell me if you tend to trust it or tend not to trust it. The National Government’. Respondents can then choose between ‘Tend to trust’, ‘Tend not to trust’ or ‘Don’t Know’.

Net public support measures are constructed as the number of ‘For’ responses minus ‘Against’ responses, according to the expression: Net support = (For – Against)/(For + Against + Don’t Know). Net trust measures are constructed as the number of ‘Tend to trust’ responses minus ‘Tend not to trust’ responses, according to the expression: Net trust = (Trust – Tend not to trust)/(Trust + Tend not to trust + Don’t Know).

5 Descriptive Results

This section describes how support and trust have evolved since the start of the euro as a virtual currency in 1999. We focus first on the whole euro area, then move to individual euro area members and finally to the non-euro area members of the EU. In addition, we account for major differences in the pattern of support for the euro and of trust in the ECB following the crisis that started in 2008.

5.1 Support and Trust in the Euro Area

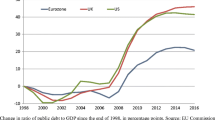

Figure 1.1 plots public support for the euro and trust in the institution that carries out monetary policy in the euro area – the European Central Bank – and trust in the national governments across the 19 member countries in the euro area as well as the unemployment rate in the euro area. We can draw four central findings from the patterns shown.

Unemployment and net support for the euro and net trust in the ECB and in the national government, average EA19, 1999–2018

Notes: The left-hand y-axis plots unemployment ranging from 7.3% to 12.1%. The right-hand y-axis displays net support/trust in percentage. Since the figure depicts net support/trust, all values above 0 indicate that a majority of the respondents support the euro and trust the ECB. The dashed lines distinguish the physical introduction of the euro in January 2002, the start of the financial crisis in September 2008 and the start of the recovery at the end of 2013. The averages for EA19 are weighted by population.

Source: Standard Eurobarometer data 51–90.

First, we see that a large majority supported the euro (>30%) during the first two decades of its existence. Second, while a large majority trusted the ECB before the 2008 crisis, only a minority of citizens expressed trust in their national government. Third, while the large majority of support for the euro was only slightly dented by the sharp increase in unemployment during the crisis years of 2008–2013, trust in the ECB and in national governments was strongly negatively affected by the crisis, with the ECB losing the trust of a majority of citizens surveyed and the national governments entering the territory of large mistrust (<−50%).

Fourth, and finally, the recent recovery in the EA has led to a clear rise in support for the euro from November 2013 onwards, reaching the average value of 55% in 11/2018, and thus nearly reaching the peak value of 56% from March to May 2003. The economic recovery also led to a recovery in trust in the national government to a level higher than in the pre-crisis period and a recovery of trust in the ECB. The latter has nearly re-established a majority level of trust, but one not high enough to make up for the decline during the crisis (see Table 1.A1 in this contribution Appendix).

5.2 Support and Trust among Individual Euro Countries

Let us now turn to the data for each member state. What do we learn from the disaggregated pattern? Figure 1.2 displays the pattern in each member state of the EA19, split into an EA12 country sample in Fig. 1.2a and the EA7 countries in Fig. 1.2b, which joined the EA after 2001 (for a figure showing all 19 individual members, including the unemployment rate, see Fig. 1.A1 in this contribution Appendix).

We identify three striking results. First, with the exception of Greece and Finland in the pre-crisis time and Cyprus in the time of crisis, a majority of citizens express support for the euro in each individual EA economy. Second, while there is only a slight decline in support for the euro during the crisis, we detect pronounced losses in trust in the ECB and national governments, particularly in the periphery countries of the EA, namely Spain, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and Cyprus (see also Table 1.A1 in this contribution’s Appendix). Third and finally, during the recovery, a pronounced increase in public support for the euro is apparent in almost all countries. A strong recovery in trust in the ECB as well as in the national government is also registered in some periphery countries. The loss in trust has been more than restored in two countries, namely Portugal and Ireland, but this has not happened in Spain and Greece.

5.3 Support and Trust outside the Euro Area

How did public support for the euro and trust in the European Central Bank and the national government evolve outside the member countries of the euro area? Figure 1.3 reveals four patterns worth noting.

First, public support for the euro is substantially lower outside the EA than inside, particularly in the United Kingdom, Sweden, the Czech Republic, and Denmark. The case of Denmark is interesting, given that the country has de facto tied its currency to the euro since the start of the common currency. Second, support for the euro declined in a pronounced manner following the euro crisis in all non-euro member states. Third, we detect a recovery in support since November 2013, particularly in the United Kingdom. The euro currently enjoys a fairly high level of support – compared to its time-series pattern – although it is still negative. Fourth, in the three older EU member states, Sweden, Denmark and the United Kingdom, trust in the ECB and in the national government is higher than support for the euro. In the new member states, trust in the national government is significantly lower than trust in the ECB and support for the euro.

6 Econometric Results

We now turn to some econometric evidence. To analyse the channels that influence public support for the euro and trust in its governance, we adopt a model specification used by Roth et al. (2016, 2019). We estimate support for the euro and trust in the ECB as a function of unemployment, inflation, growth in real GDP per capita, and control variables deemed of potential importance in explaining the within the variation of support. Our baseline model (1.1) reads:

where Support/Trustit is the net support for the euro and net trust in the ECB for country i during period t. Unemploymentit, Inflationit, Growthit, and Zit are, respectively, unemployment, inflation, growth of GDP per capita and control variables deemed of potential importance lumped together in Z,Footnote 1,Footnote 2αi represents a country-specific constant term (fixed effect), and wit is the error term.

We estimate Eq. (1.1) by means of DOLS (dynamic ordinary least squares),Footnote 3 a method that permits full control for endogeneity of the regressors. To correct for autocorrelation,Footnote 4 we apply FGLS (Feasible General Least Squares) procedure.Footnote 5 Both applications lead to the following Eq. (1.2), representing our FE-DFGLS (Fixed Effect Dynamic Feasible General Least Squares) approach – for a detailed explanation of the FE-DFGLS approach, see Roth et al. (2016, 2019):

with αi being the country fixed effect and Δ indicating that the variables are in first differences. Applying DFGLS, Unemployment, Inflation and Growth turn exogenous and the coefficients β1, χ1, δ1 and ϕ1 follow a t-distribution. This property permits us to derive statistical inferences on the causal impact of unemployment, inflation, and growth. The asterisk (*) indicates that the variables have been transformed and that the error term uit fulfils the requirements of the classical linear regression model.

Table 1.1 shows the econometric results for Eq. (1.2) within our EA19 country sample. Analysing the full period from March–April 1999 to November 2018, we detect unemployment to be a significant factor behind public support for the euro, trust in the ECB and trust in the national government (regressions 1, 4, and 7 in Table 1.1).

A 1%-point increase in unemployment is associated with a decline in net support by 1.3 percentage points. The effect is threefold in trust in the ECB and in national governments, with an estimated coefficient of −4.2 and −4.6, respectively.

Analysing the pre-crisis sample (regressions 2, 5 and 8 in Table 1.1), we find unemployment to be insignificantly related to public support for the euro and to trust in the ECB and only slightly significantly related to trust in the national government. However, we find a highly significant and strong effect of inflation on public support for the euro (−14.9). Studying periods of crisis and recovery (regressions 3, 6 and 9 in Table 1.1), it is clear that the negative unemployment coefficient from the full sample is driven by the crisis-recovery period. We detect a highly significant and negative coefficient between unemployment and net support for the euro (−2.1) and net trust in the ECB and the national government (−3.4 and respectively −3.7) during the crisis.

To untangle the effects of the crisis-recovery, Table 1.2 splits the crisis-recovery period into a crisis phase 2008–2013 and a recovery phase 2013–2018. When analyzing the crisis period 2008–2013 (regressions 2, 5 and 8 in Table 1.2), we find that whereas the unemployment increase in times of crisis slightly dented public support for the euro (–0.8), it had a six-fold impact on trust in the ECB (–5.3) and a four-fold impact on trust in the national government (–3.5).

In analysing the recovery period (regressions 3, 6 and 9 in Table 1.2), we detect a four times larger coefficient for public support for the euro (−3.6) compared to the crisis period, which indicates a rising effect during the recovery in which a 1 %-point decline in unemployment leads to an increase of 3.6 percentage points of public support. The unemployment decline during the recovery more than fully makes up for the decline during the crisis. The same pattern holds for trust in national governments. The compensation effect (−4.1) during recovery is larger than the losses during the crisis (−3.5). It was only in analyzing trust in the ECB that we found a different pattern. The pronounced loss in trust during the crisis due to the sharp rise in unemployment (−5.3) has only partially been restored during the recovery (−2.2).

To sum up the econometric work, the rate of unemployment emerges as a key factor determining support for the euro and trust in the ECB and in national governments.

7 Explaining the Divergence in Support for the Euro and Trust in the ECB

Our descriptive and econometric findings highlight an intriguing difference in EA citizens’ public support for the euro and their trust in the ECB. Before the crisis, the two sets of time series were stable and strongly correlated at a relatively high level (see Fig. 1.1). This pattern changed during the crisis (2008–2013), which brought about a sharp fall in trust in the ECB, while support for the euro declined only slightly. During the recovery (2013–2018), when unemployment started to decline, support for the euro began to rise. Although the same holds for trust in the ECB, the recovery was far more modest. In 2018, the gap between the two series remains much larger than during the pre-crisis period.

How can we explain this difference over time? We suggest that the public makes a distinction between the role of the euro as the currency per se and the role of the ECB as the central bank that supplies the currency and frames monetary policy.

When asked about the euro, the public most likely considers how well the euro performs the standard micro-functions of money, traditionally expressed as that of a medium of exchange, a store of value and a unit of account. The euro has served the public well on all three accounts, particularly as a source of stable purchasing power. Inflation in the euro area has been low and fairly constant since the introduction of the euro, in sharp contrast with the inflationary history of several euro-area members.

This stability is a likely factor behind the support for the euro as a currency even during the crisis years of 2008–2013. Indeed, this line of reasoning is confirmed by our econometric findings, which depict a strong negative relationship between inflation and public support for the euro during the crisis period.

When asked about trust in the ECB, the respondents turn their attention from the micro-issues related to the euro as the money they use in daily business and commerce to the macro-problems related to monetary policy, interest rates, unemployment, and crisis management. Most likely, they hold the ECB responsible for the state of the macroeconomy, or at least jointly with other actors such as national governments, as reflected in the decline in trust in the ECB in parallel with the fall in trust in national governments during the euro crisis. During this crisis, the ECB is associated with the flow of negative macroeconomic news, such as the crisis management by countries like Greece, as a member of the troika, and the rise in unemployment due to the austerity programs launched in several euro-countries in response to the crisis.

In addition, the crisis provoked strong criticism of the ECB, which was not present during the first decade of the euro, when its launch was commonly regarded as a success. And again, our interpretation is confirmed by our econometric findings, which depict a six-fold stronger negative impact from unemployment on trust in the ECB compared to public support for the euro during the crisis period.

In short, the ECB is judged as a policymaker, whereas the euro, as a currency, is regarded as falling outside the immediate policy sphere. When its policies are viewed as being insufficient, as reflected in failing outcomes and rising unemployment, public trust in the ECB declines. When the economy of the euro area starts to improve, trust in the ECB is eventually restored.

Still, the euro crisis has left a scar on the trust invested in the ECB. The level of trust has not recovered to the level it obtained before the crisis. The gap between support for the euro and trust in the ECB suggests that it will take a long time for trust in the ECB to reach pre-crisis levels.

8 Why Is Popular Support of the Euro So Important? Two Recent Cases

We have argued that popular support of the common currency is crucial for its sustainability. Here we illustrate this argument by discussing two recent cases.

First, we suggest that the case of Italy in 2018 demonstrates how public support for the euro is crucial for the long-term survival of the common currency, in particular, if there is a loss of trust in the ECB and in the national government. After more than a decade of economic distress, higher than EA-average unemployment and lower than EA-average trust in the national government, a coalition government of major populist parties was formed in May 2018. The new coalition government intended to nominate a finance minister known to be critical of the euro. Such a nomination would have damaged cooperation among EU policymakers. The Italian president ultimately prevented the nomination.

The most likely explanation for his action is found in the fact that a majority of Italian citizens have supported the euro for over three decades, since the first plans of monetary unification were floated in 1990. Similarly, a referendum on the euro, initially considered by the populist government, was not held due to the popularity of the common currency.

In short, attempts by the Italian populist coalition government to dismantle EA cooperation were effectively countered by the popularity of the euro, serving in this way as a shield against populism. Most likely, this effect will persist in the near to medium future as well. In our opinion, a similar story has played out in France. The populist party of Marie Le Pen has dropped or at least moderated its criticism of the euro.

Second, the decision by the ECB to become the lender of last resort in the government bond market of the EA in 2012 was facilitated by the popularity of the euro. It took the ECB four years after the start of the crisis in 2008 to assume this role, but the announcement by the president of the ECB in July 2012 to ‘do whatever it takes’ swiftly resolved the sovereign debt crisis in the EA. The quantitative easing (QE) programme implemented from 2015 to 2018 also contributed to the EA’s recovery from the euro crisis. Given the loss of majority trust in the ECB during the crisis, we speculate that the large public support for the euro granted the ECB political legitimacy to secure its independence against growing criticism of its actions.

9 Conclusions

In our analysis of Eurobarometer data for the first two decades of the euro’s existence, from 1999 to 2018, we find that a majority of respondents have supported the euro in each member country of the euro area. Although the crisis in the EA led to a slight decline in public support, the recovery since 2013 has triggered an upturn in support. As the euro turns 20, the currency enjoys historically high levels of support among the citizens of the EA. A similar, although less pronounced, rise in trust in the ECB can be detected.

Looking ahead, we argue that the high esteem with which the euro is presently held by a persistent majority of citizens makes it well-equipped to weather the challenges it will surely face in its third decade. Our results suggest that keeping unemployment and inflation at bay, particularly the former, will be important for sustaining public support for the common currency and public trust in the ECB. Ultimately, euro-area citizens assess the euro and the ECB based on their economies’ performance. This reality impresses upon policymakers the need to design measures that succeed in enhancing growth and employment in the member states and thereby foster support for the common currency and trust in the ECB.

Notes

- 1.

The components of Z could potentially be macroeconomic or socio-political control variables. However, given the cointegrating relationship between support for the euro and our macroeconomic variables (see Tables 1.A3 and 1.A4 in this contribution’s Appendix), we can be confident that these Z variables do not cause bias in the coefficients of unemployment, inflation, and growth.

- 2.

Data on inflation (the change in the harmonized index of consumer prices), seasonally adjusted unemployment rates, as well as seasonally and calendar adjusted data on GDP per capita are taken from Eurostat. A summary of the data utilized can be found in Table 1.A2. The matching methodology between our macroeconomic variables and public support for the euro and trust in the ECB follows the approach of Roth et al. (2016, 2019).

- 3.

A prerequisite for using DOLS is that the variables entering the model are non-stationary and that all the series are in a long-run relationship (cointegrated). In our case, all series are integrated of order 1, i.e. they are I(1) (and thus non-stationary); non-stationarity of inflation and growth of GDP per capita is due to non-stationarity (non-constancy) of the variance of these series and they are cointegrated. The panel unit root tests and Kao’s residual cointegration test are displayed in Tables 1.A3 and 1.A4 in this contribution’s Appendix.

- 4.

We found first-order autocorrelation to be present.

- 5.

FGLS (in the ready-to-use EViews commands) is not compatible with time-fixed effects. It picks up shocks and omitted variables in the period of study. In addition, it has been found that running the regression with time-fixed effects (without applying FGLS) does not tackle the problem of autocorrelation of the error term.

References

Baldwin, R. E., & Wyplosz, C. (2019). The economics of European integration. McGraw-Hill.

Banducci, S. A., Karp, J. A., & Loedel, P. H. (2003). The euro, economic interests and multi-level governance: Examining support for the common currency. European Journal of Political Research, 42(5), 685–703.

Banducci, S. A., Karp, J. A., & Loedel, P. H. (2009). Economic interests and public support for the euro. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(4), 564–581.

Bordo, M. D., & Jonung, L. (2000). Lessons for EMU from the history of monetary unions, with an introduction by Robert Mundell, IEA readings 50. Institute for Economic Affairs, London.

Bordo, M. D., & Jonung, L. (2003). The future of EMU: What does the history of monetary unions tell us? In F. Capie & G. Woods (Eds.), Monetary Unions: Theory, History, Public Choice (pp. 42–69). Routledge.

Deroose, S., Hodson, D., & Kuhlmann, J. (2007). The legitimation of EMU: Lessons from the early years of the euro. Review of International Political Economy, 14(5), 800–819.

European Commission (2018). Standard Eurobarometer nos. 51–90. European Commission.

Frieden, J., & Walter, S. (2017). Understanding the political economy of the eurozone crisis. Annual Review of Political Science, 20, 371–390.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2016). Monnet’s error? Economic Policy, 31(86), 247–297.

Hobolt, S. B., & Leblond, P. (2014). Economic insecurity and public support for the euro: Before and during the financial crisis. In N. Bermeo & L. M. Bartels (Eds.), Mass politics in tough times (pp. 128–147). Oxford University Press.

Hobolt, S. B., & Wratil, C. (2015). Public opinion and the crisis: The dynamics of support for the euro. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2), 238–256.

Kaltenthaler, K., & Anderson, C. (2001). Europeans and their money: Explaining public support for the common European currency. European Journal of Political Research, 40(2), 139–170.

Mundell, R. (1961). A theory of optimum currency areas. American Economic Review, 54(4), 657–665.

Roth, F. (2015). Political economy of EMU: Rebuilding systemic trust in the euro area in times of crisis. DG ECFIN’s European economy discussion paper 16.

Roth, F., Baake, E., Jonung, L., & Nowak-Lehmann D., F. (2019). Revisiting public support for the euro: Accounting for the crisis and the economic recovery, 1999–2017. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(6), 1262–1273.

Roth, F., Jonung, L., & Nowak-Lehmann D., F. (2016). Crisis and public support for the euro, 1990–2014. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(4), 944–960.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2016). The euro. Penguin Books.

Verdun, A. (2016). Economic and monetary union. In M. Cini & N. Borragan (Eds.), European Union Politics (pp. 295–307). Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Roth, F., Jonung, L. (2022). Public Support for the Euro and Trust in the ECB: The First Two Decades of the Common Currency. In: Public Support for the Euro. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86024-0_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86024-0_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86023-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86024-0

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)