Abstract

In this chapter, I tell the story of the waxing and waning of the status of the traditional birth attendant (TBA) in global maternal health policy from the launch of the Safe Motherhood Initiative in 1987 to the present. Once promoted as part of the solution to reducing maternal mortality, the training and integration of TBAs into formal healthcare systems in the global south was deemed a failure and side-lined in the late 1990s in favour of ‘a skilled attendant at every birth’. This shift in policy has been one of the core debates in the history of the global maternal health movement and TBAs continue to be regarded with deep ambivalence by many health providers, researchers and policymakers at the national and global levels. In this chapter, I take a critical global heath perspective that scrutinises the knowledge, policy and practice of global health in order to make visible the broader social, cultural and political context of its making. In this chapter, I offer a series of critiques of global maternal health policy regarding TBAs: one, that the evidence cited to underpin the policy shift was weak and inconclusive; two, that the original TBA component itself was flawed; three, that the political and economic context of the first decade of the SMI was not taken into account to explain the failure of TBAs to reduce maternal mortality; and four, that the reorganisation of the Safe Motherhood movement at the global level demanded a new humanitarian logic that had no room for the figure of the traditional birth attendant. I close the chapter by looking at the return of TBAs in global level policy, which, I argue, is bolstered by a growing evidence base, and also by the trends towards ‘self-care’ and point-of-use technologies in global health.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- traditional birth attendants

- Safe Motherhood Initiative

- maternal health

- global health policy

- critical global health

- self-care initiative

A Midwife by Any Other Name

In 2002, the International Confederation of Midwives met for their triennial Congress in Vienna. I attended as a medical anthropologist visiting a field site: mingling with participants, listening to research presentations, learning about how the profession was organised in different countries and hearing about the pleasures and challenges midwives faced in their everyday work. At a panel one afternoon, an Australian midwife gave a paper critical of what was at the time the relatively new World Health Organization (WHO) ‘skilled attendant’ policy. The WHO had officially abandoned the training of Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) as a component of its maternal health policy and turned instead to the goal of ensuring a skilled attendant at every birth. The presentation had the feel of an exposé and murmurs began to ripple throughout the auditorium. During the discussion period, a heated debate broke out. Some midwives hailed the beginning of the end of community-level traditional birth attendants who they saw as ineffective (at best) and dangerous (at worst). Others decried the new policy as an act of selling out ‘their sisters’ in other parts of the world. Some midwives spoke positively of their experiences training TBAs as part of their work on Safe Motherhood projects while others had come away from such experiences quite unconvinced. An anthropologist in the room weighed in, suggesting the word TBA itself was problematic. ‘It’s become pejorative’ she said. ‘If a woman attends another woman in childbirth, she is a midwife’. Canadian, American and New Zealand midwives stood out in their defence of TBAs and their criticism of the official withdrawal of support for them at the level of global policy. Their perspective made sense given the grassroots origins of midwifery as a social movement in these jurisdictions where midwives had often trained by apprenticeship, practiced outside the formal healthcare system and had struggled to become recognised as legal and legitimate. Talk soon turned to the role of the International Confederation of Midwives on the issue. ‘I would like to see the ICM embrace this workforce as sisters’, stated one American midwife present. But the Ghanaian midwife who was moderating the session shook her head and closed the session, saying ‘TBAs should be eventually replaced entirely by midwives, even though midwives must try to work with them now out of necessity’.

The next day, an ad hoc group calling itself the Committee to Promote Inclusiveness was struck and a meeting planned with the intention of pressing the ICM to develop a position statement on the TBA question. The ICM was in a difficult position. Midwives’ professional standing was dependent on an exclusionary definition that had been developed with the WHO and the Federation International de Gynecologues et Obstetriciens (FIGO) (ICM, 2005). To acknowledge TBAs as their near equivalents was fundamentally at odds with the concept and parameters of a health profession. It was also argued at meetings I attended that such a move would jeopardise the standing of midwifery in the eyes of other health professions and the relatively recent place of the ICM at the table in policy decisions regarding major global maternal health initiatives. Not long after the Vienna Congress, the ICM did make its position clear. In 2004 the ICM signed a joint statement with the WHO and FIGO called ‘Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant’. The statement defines a skilled attendant as ‘an accredited health professional – such as a midwife, doctor or nurse – who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns’ (2004, p. 1). In this document, TBA training appears in a shaded box as a ‘lesson learnt’. The TBA experiment at the level of global maternal health policy appeared to be well and truly finished.

Introduction

In this chapter, I tell the story of the waxing and waning of the status of the traditional birth attendant in global maternal health policy from the launch of the Safe Motherhood Initiative in 1987 to the present. Once promoted as part of the solution to reducing maternal mortality, the training and integration of TBAs into formal healthcare systems in the global south was deemed a failure and side-lined in the late 1990s in favour of ‘ensuring a skilled attendant at every birth’ (Starrs, 1997, p. 28). And yet as the opening vignette reveals, the shift in policy was a matter of some debate. In fact, the TBA question – whether and how to effectively engage TBAs in the effort to reduce maternal mortality globally – has been one of the core policy debates in the history of the global maternal health movement and TBAs continue to be regarded with deep ambivalence by many researchers and policymakers at the national and global levels, not to mention front-line healthcare providers (Campbell et al., 2016; Prata et al., 2011). In the wake of the policy shift, TBAs did not go away, though the programmes to train and support them often did. Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and national health systems focused their efforts elsewhere as funding dried up for such projects and research. And so began an era of policy retreat with regard to TBAs at the global level, which continues in large part today. In major statements and position papers, the training and formal integration of TBAs in the past appears as a policy that did not produce results, advisable only as a stopgap measure or last resort (Starrs, 1997; WHO, 2005). Yet TBAs continue to practice and participate in maternal health projects in many countries with varying degrees of inclusion within formal healthcare systems. In contrast some national-level health ministries have taken strong stances, veering towards outright bans in national level rhetoric, if not in formal policy (Murigi & Ford, 2010; Whitaker, 2012; Rudrum, 2016; Haruna et al., 2019).Footnote 1 Thus, the policy retreat at the global level mixed with a diversity of local realities has contributed to widespread policy and practical ambivalence and tension amongst health policy researchers, practitioners and advocates who make up the global maternal health community.

I approach the topic of the TBA question in global maternal health policy from a critical global heath perspective, that is, from a perspective that scrutinises the knowledge, policy and practice of global health with the goal of making visible the broader social, cultural and political context of its making. Joao Biehl’s (2007) notion of the ‘policy space’ captures the complexity of the shifting assemblages of actors and non-neutral interests out of which policymaking emerges: political ideologies, moral investments, professional interests, scientific cultures and new technologies as well as market forces and trade agreements that structure and constrain the flow of money, people, ideas and goods. Critical global health scholarship shares much in common with the health policy and systems research (HPSR) agenda defined by Sheikh and colleagues (Sheikh et al., 2011) in terms of its attention to wider influences and micro processes that shape the multiple levels of policy decisions and practices and sees them as non-neutral (see also Biehl, 2007; Gilson, 2012; Walt et al., 2004). In contrast to HPSR researchers who set out to study policy, anthropologists tend to bump into policy in the field while doing other things; in my case, it was while tracking the emergence of midwifery as a profession on the global stage. Also, anthropologists tend to focus on the local context initially and track policy upwards to its national or global level origins. Amongst the shared goals and perspectives of these critical approaches to the study of global health policy, however, is that knowledge produced by looking critically at the making and practice of policy ought to inform the policymaking process itself.

In this chapter, I focus on four key critiques of the TBA policy shift that illuminate both the limitations of the original TBA intervention that contributed to the shift and broader social, scientific and political context of its making, including: one, that the evidence cited to underpin the policy shift was weak and inconclusive; two, that the original TBA component itself was flawed in its failure to account for cultural specificity; three, that the political and economic context of the first decade of the Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) that constrained its implementation was not taken into account; and four, that the reorganisation of the Safe Motherhood movement at the global level demanded a new humanitarian logic that had no room for the figure of the traditional birth attendant. I present these critiques not only as backdrop for the TBA debates but as a way to illuminate the forces that shape the complex policy space of global maternal health policy.

Some scholars have begun to call for ‘the return of the traditional birth attendant’ as a partner in the effort to improve maternal health globally (Lane & Garrod, 2016). Meanwhile, a growing number of NGOs are re-engaging TBA-like community health actors as important players in the deployment of new technologies and drugs for maternal health alongside nurses, midwives or physicians or in some cases on their own. In the final section of this chapter, I track the TBA question to the present, observing that the once polarising figure of the TBA has been re-engaged by a set of trends in global health more broadly, including the push for new technological innovations, the rise of evidence-based medicine and advocacy, and the new self-care agenda of the WHO.

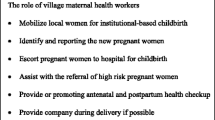

The Traditional Birth Attendant: A Global Health Invention

As early as 1975 the TBA was defined in WHO guidelines as ‘a person (usually a woman) who assists the mother at birth, and who initially acquired her skills delivering babies by herself, or by working with other TBAs’ (Verderese & Turnbull, 1975, p. 18). UNICEF and other UN agencies, and national ministries of health had been training TBAs for decades and several international and regional technical consultations had been undertaken by the WHO in the 1970s to explore the potential of traditional birth attendants as resources in the domain of maternal health, as a way to extend the reach of limited health services in developing countries (Mangay Maglacas & Simons, 1986; WHO, 1979; WHO, 1985).

The launch of the Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) by the World Health Organization, the World Bank and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in 1987 formalised and extended the training and integration of TBAs throughout the Global South as a component of a larger package of activities including greater access to family planning, the upgrading of perinatal services to approximate western biomedical standards (especially in the area of emergency obstetric care) and making improvements in the scope and quality of education for midwives and TBAs (Starrs, 1987; WHO, 1994). The Safe Motherhood Declaration challenged all nations of the world to halve their maternal mortality figures by the year 2000. The TBA component of the SMI was in keeping with the comprehensive Primary Health Care (PHC) vision of Alma Ata, which had sought to decentralise healthcare services in part by recognising the importance of local knowledge and valorising the participation of local practitioners – including traditional medical practitioners and birth attendants (WHO, 1978). As the practical guidelines for implementing Safe Motherhood programming – a document called the Mother Baby Package – stated, ‘[i]n countries were TBAs attend a large proportion of home deliveries, training courses can be effective in upgrading their knowledge. Training of TBAs should be seen as a way of bridging the gap until all women and children have access to acceptable, professional health services’ (WHO, 1994, p. 15).

Commentaries, reports and discussion papers throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s take a measured but positive approach to TBAs as part of the SMI. A World Bank discussion paper, for example, situates TBAs as potentially effective with training and liaison (1993 p. 15) and goes on to list the tasks and skills envisioned for them: being trained to conduct uncomplicated deliveries, reduce infections, detect complications of pregnancy and make referrals to skilled providers in the formal healthcare system when necessary. Over the next decade, thousands of women throughout the Global South – some with experience attending births and some without – were identified, trained and deployed as TBAs. They were meant to be linked to healthcare facilities and receive collaboration and support from local higher-level healthcare providers.

In 1997, top international reproductive health policymakers, researchers and stakeholders met in Colombo, Sri Lanka for a Technical Consultation on the SMI. After a decade of policy implementation, maternal mortality rates in most impoverished countries remained unchanged. The technical consultation report, The Safe Motherhood Agenda: Priorities for the Next Decade (Starrs, 1997) reflected on the first ten years of the SMI and specified 10 priorities for the next decade of policy development and intervention. Amongst them the priority to ‘Ensure skilled attendance at delivery’ was identified as the ‘single most critical intervention’ for safe motherhood (Starrs, 1997, p. 28). As defined in this document, ‘A skilled birth attendant can be a midwife, a nurse with additional midwifery education, or a physician with appropriate training and experience, but does not include traditional birth attendants’ (Starrs, 1997, p. 29; See also, WHO, 1985). The report from the SMI summarised the scant evidence that existed and concluded that TBAs were ‘proven’ to be ‘not effective’ in reducing rates of maternal mortality and that training them was a waste of resources (Starrs, 1997, p. 30). Some responsibility was placed on the TBA component of the original SMI as one of the weak links in the overall programme due to their illiteracy and lack of uptake of scientific knowledge. Historical evidence that improvements in MMR were only realised in other nations with the advent of comprehensive primary healthcare services with professional providers – including emergency obstetric care – was also brought to bear on the decision (Loudon, 1992; de Brouwere et al., 1998).Footnote 2

More nuanced versions of the evidence later emerged. Bergstrom and Goodburn (2001) reported on a small range of studies which showed the limitations of what TBAs could do in constrained circumstances as well as how they could be part of successful comprehensive approaches. They also noted the near impossibility of correlating TBA inclusion or exclusion to mortality outcomes given the absence of vital registration systems in most countries at that time. They concluded that TBAs, while still the main caregivers for vast numbers of women, should be given low priority. Likewise, van Lerberghe and De Brouwere, in their analysis of the existing literature, while sympathetic to some of their ‘other merits’ ultimately discredit TBAs on three counts: their ‘resistance (or inability) to change’, ‘their lack of credibility in the eyes of the health professionals’ and ‘the de facto impossibility to organise effective and affordable supervision’ (2000, p. 19). A close look at this statement reveals that all three points have not to do with TBAs but with health providers’ attitudes and health systems’ weaknesses. Their conclusions nevertheless align with the official position of the technical consultation report.

A new initiative was subsequently launched called ‘Making Pregnancy Safer’ which explicitly marginalised the TBA component of the SMI in favour of the goal of ensuring a ‘skilled attendant at every birth’ (WHO, 2004) employing a definition, like the one offered above, which excludes TBAs (Safe Motherhood Interagency Group, 2002). The new initiative also promoted birth in health facilities rather than in the community. In the years following the shift, the narrative of disappointment, failure and lessons learnt on the TBA component of the SMI solidified in both global health policy documents and the research literature on TBAs.Footnote 3 For example, in a shaded box entitled ‘Traditional birth attendants: another disappointment’ in the 2005 World Health Report, the authors look back on the TBA component of the SMI with these words: ‘The strategy is now increasingly seen as a failure. It will have taken more than 20 years to realise this and the money spent would perhaps in the end have been better used to train professional midwives’ (WHO, 2005, p. 70; see also Adegoke & van den Broek, 2009).

Critical Perspectives on the TBA Policy Shift

As the opening vignette from the ICM reveals, the official end of policy support for the TBA component of the SMI was a matter of deep ambivalence for professional midwives. It continued to be a question for further discussion and debate in the scientific community as well. Anthropologists, midwife-scholars and global health researchers have all been involved in aspects of the debate, four key themes of which I present below: one, that the evidence cited to underpin the policy shift was weak and inconclusive; two, that the original TBA component itself was flawed in its failure to account for cultural specificity; three, that the political and economic context of the first decade of the SMI was not taken into account to explain the failure of TBAs to reduce maternal mortality; and four, that the reorganisation of the Safe Motherhood movement at the global level demanded a new humanitarian logic that had no room for the figure of the ‘traditional’ birth attendant.

A Question of Evidence

As I described in the previous section, in the report of the technical meeting held in Colombo, Sri Lanka in 1997 to evaluate the first decade of the SMI, it was argued that the withdrawal of support for TBA training was based on evidence that TBAs had been ineffective in reducing maternal mortality as measured by the lack of reduction in the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) over the previous ten years (Starrs, 1997; see also Starrs, 2006). Yet research on the effectiveness of training TBAs at that time was quite limited. Studies were varied in focus, and collectively the message they delivered was mixed and inconclusive.

Some scholars reviewing this evidence responded directly to the question of evidence upon which the policy shift was said to be based. For example, midwife scholar Sue Kruske and anthropologist Lesley Barclay published a paper not long after the ICM Congress arguing that the new policy was misguided: first, they argued that a focus on a single indicator – the MMR – was a gross reduction of the idea of effectiveness. Second, they noted that by narrowly focussing on the ‘obstetric skills’ in the new skilled birth attendant (SBA) definition (which TBAs did not possess) the policy ignored other skills and expertise that they did possess – social and cultural skills, in their words – which they argued did contribute to the less reductionist goal of improving maternal health care (Kruske & Barclay, 2004).

Echoing this observation about the narrowness of the goal, nursing and public health scholar Lynn Sibley and colleagues published a series of summaries and systematic reviews of the evidence concerning TBAs in the early 2000s that added nuance to the understanding of their roles and potential in maternal and child health. A 2004 meta-analysis of studies looked not at whether TBA training reduced maternal mortality per se, but as ‘a behaviour change strategy to increase women’s use of [antenatal care] services provided by skilled health professionals’ (Sibley et al., 2004, p. 298). Despite noting variations in how TBAs were trained in the studies they looked at, the authors found significant positive associations between trained TBAs and antenatal care (ANC) attendance, concluding that ‘TBAs could play an important role in influencing women’s ANC attendance in settings where TBAs are respected, active, and where their activities extend beyond birthing services to include health promotion in the community at large’ (2004, p. 303). Sibley & Sipe’s 2006 study on the effectiveness of TBA training demonstrated that it was associated with ‘moderate to large improvements in behaviours relating to selected intrapartum and postnatal care practices and small but significant decreases in perinatal mortality’ (2006, p. 474). They concluded with the argument that TBA training in settings where women do not have access to properly staffed or stocked facilities is an ethical imperative. Other research showed the promise of TBAs as conduits for health promotion (Eades et al., 1993) and referrals (O’Rourke, 1995).

As existing evidence on TBA participation in the SMI was reviewed and synthesised and new studies emerged, a scientific narrative began to emerge that countered the narrative of disappointment, failure and lessons learnt. It called for research that could illuminate the work of TBAs, the content of their training programmes and their relationships with the formal healthcare system with more nuance and specificity. It proposed different questions that looked at how TBAs could increase the use of ANC with skilled providers, for example, rather than trying to demonstrate a direct correlation between TBAs and the reduction of maternal mortality ratios.

In addition to the call for generating new evidence there was a call for a change in perspective. As Sibley, Sipe and Koblinsky wrote: ‘There is an urgent need to improve capacity for evaluation and research on the effect of TBA training programs and other factors that influence women’s use of ANC’ (2004, p. 298). It was, in effect, a call for turning the lens back onto science and policymakers themselves for their failure to understand the roles TBAs played and might play in locally variable maternal healthcare landscapes. Kidney et al. similarly concluded that community-level strategies had yet to be properly evaluated and recommended further study on how interventions involving TBAs actually work in a range of specific contexts (2009, p. 8). The discussion sections of several such studies are careful to refer to the original vision of TBA training and integration within the SMI: that TBAs had been meant to work as points of articulation between communities and a functioning healthcare system – including emergency obstetric care – extending its reach rather than as primary care practitioners responsible for the reduction of the national MMR. This scientific counter narrative, formed in the wake of the policy shift, was that it was lack of appropriate evidence that had doomed the TBA component of the SMI.

The fulfilment of this research agenda to look more closely at the work of TBAs in their local contexts in order to build a robust, context-specific evidence base was soon overshadowed, however, by two powerful, inter-related trends in the broader global health research field. First was the rise of evidence-based medicine (EBM), that is, the use of systematically derived clinical evidence to guide clinical practice and the concomitant rise of evidence-based policy-making (EBPM) to guide the selection and implementation of interventions and their evaluation. Second was the demand for more and better metrics to describe and compare in quantitative terms the scope of various global health problems and the interventions used to address them. Both trends were sector wide and had the effect of shifting research focus back towards the evaluation of targeted interventions rather than comprehensive analyses and strengthening of health systems which was roundly acknowledged as the key to ensuring safe motherhood (Storeng, 2010). ‘Playing the numbers game’ was a calculated advocacy strategy within the global maternal health community to reframe the problem of maternal mortality and its solutions in ways that would appeal to political decision makers and funders (Storeng & Béhague, 2014). Better quantitative data made the sheer magnitude of the problem of maternal mortality globally – and disparities between nations – into numbers that were hard to ignore. Maternal mortality ratios and related indicators could also be deployed as a tool of accountability against governments (Adams, 2016; Wendland, 2016). The EBM paradigm already had caché in University-based research cultures and the lack of an evidence basis for much of obstetrics in high-income nations prior to this time added to the pressure to demonstrate the evidence basis for interventions into maternal health in global health settings (Campbell & Graham, 2006; Storeng, 2010). By taking up EBM and endorsing the pursuit of better metrics, the global maternal health advocacy community was able to legitimise and secure the profile of the cause on the global stage. In 2000 the reduction of maternal mortality was named as one of the Millennium Development Goals – but that same context, as Storeng and Béhague (2014) have argued lead to the ‘technocratic narrowing’ of the SMI in terms of the means by which the goal would be accomplished, tending strongly towards quick fixes and vertical interventions rather than comprehensive health systems improvements into which TBA-like providers might fit and where their contributions might be evaluated through research.

Flaws in the Original TBA Intervention

Anthropologists had another critique of the policy shift: they argued that TBAs had not been properly understood in the first place and therefore were not deployed in ways that were appropriate or useful. As the TBA experiment under the auspices of the SMI unfolded, anthropologists researching midwifery and childbirth around the world were in the position to contribute evidence about the roles TBAs were already playing in various settings and what roles they could be expected to play in improving maternal health and reducing suffering and death. On the one hand, anthropologists had documented a vast range of practices and practitioners of birth – and yet they also tended to be in support of the idea of a category of person resembling the TBA. Variously called traditional midwives, parteras, matrones, community midwives, apprentice-trained midwives and many other local names, anthropologists generally sought to illuminate their contributions to maternal and infant health as well as social well-being (Cosminsky, 1977; Jordan, 1989; Laderman, 1983; Sargent, 1989).

Anthropologists were also in a position to contribute descriptive evidence about TBA training programmes and related interventions. Even before the launch of the SMI, Brigitte Jordan, for example, had described ineffective and inappropriate methods used in the training of Maya midwives in the Yucatan: didactic rather than hands-on learning, lack of cultural sensitivity by trainers towards parteras and no follow-up (1978). As the SMI got underway a decade later such critiques continued to surface. Carol MacCormack (1989) described how the SMI guidelines for identifying women to be trained as TBAs did not consider factors of ethnicity, caste, language, religion or kinship – which can often figure more significantly than training in the choice of a birth attendant. In my own work I have described the ill-fit between the scope of practice for TBAs imagined by global policy and local realities in Malawi where TBAs were assumed to be in the best position not only to catch babies but also to give prenatal care and contraceptive advice when in fact these tasks were neither traditional nor – in the case of dispensing contraceptive advice – appropriate to their scope of practice. Consequently, they refused to carry them out (MacDonald, 2017). Additionally, scholars noted that government ministries and NGOs often favoured training programmes for TBAs more for economic and political reasons than out of regard for traditional knowledge (Viisainen, 1992) and because trainings could be counted to demonstrate SMI activity regardless of the quality of the training or any outcomes it produced (AbouZahr, 2003). Thus, trainings were implemented in a ‘selective’ rather than ‘comprehensive’ way.

Some anthropologists called into question the very notion of a TBA. Stacy Leigh Pigg (1997), for example, noted that in Nepal there was no local equivalent of the TBA; the women who came forward to receive training under SMI programmes had no special clinical experience or expertise with childbirth; rather, they attended births as ritual specialists, while the maternal kin of the birthing women handled the labour and delivery. TBAs in Nepal, Pigg argues, had to be ‘invented’ to fit SMI activities and ultimately functioned in service of the development paradigm rather than in the lives of women and newborns. Denise Roth Allen observed something similar in Tanzania in Sukuma communities, in which many women gave birth with female relatives or alone and there was no distinct tradition of midwifery. By her reckoning one third of women trained as TBAs by a local SMI project that she studied in the 1990s had never attended a birth before. It is no wonder, she concludes, that local women perceived the newly designated TBAs as risks rather than assets and that the entire scheme failed to produce the results policymakers and programme planners had hoped for (1994, p. 115).

This body of anthropological research speaks to flaws in the original SMI policy and its implementation rather than the failure of TBAs to learn or practice in helpful ways. In sum, anthropological knowledge indicated the variability of birth culture and birth attendants around the world and thus the imperative of policies that could grapple with the particulars of a setting rather than the imposition (however well-intentioned) of an ideal model. What I call the ‘universal TBA’ (MacDonald, 2017) is an example of Olivier de Sardan et al.’s ‘traveling model … developed by international experts and introduced in an almost identical format across numerous countries to improve some aspect of maternal health systems in low-and middle-income countries’ (2016, p. 71). When confronted with actual contexts in which these standardised models are supposed to function, their argument continues, it results in ‘drifts, distortions, dismemberments and bypasses’ (2016, p. 71). The universal TBA, I suggest, also assumes a universal ‘third world woman' (Mohanty, 1991) whom we are to assume prefers the TBA for reasons of culture and tradition, rather than as a rational assessment of risks presented by inexperienced and poorly trained birth attendants, on the one hand, and treacherous and costly trips to potentially understocked and understaffed health facilities, on the other.

The irony is that the SMI had tried to acknowledge and incorporate local systems of birth attendance rather than stamp them out. But the local imagined by the SMI was paradoxically too general; the TBA was imagined as a universal type. Not only did the focus on the universal characteristics of traditional birth attendants problematically essentialise roles for both childbearing women and birth attendants in diverse cultural settings, but the invention and implementation of the universal TBA had more insidious consequences as well. Women’s inability or unwillingness to conform to roles designated for them by SMI policy was construed as their inability or unwillingness to modernise. A consequence of this traveling model not working to plan was that blame was cast not on the model itself, but on those who were meant to model it. Thus, TBAs came to be seen as obstacles to development – as vestiges of underdevelopment – for their failure to take on these new roles designated for them by SMI policy. In global health the notion of tradition as a ‘cultural barrier’ to change has often functioned as a stand-in for the decision-making processes of real people in constrained circumstances when their decisions do not resemble a biomedical itinerary. Anthropologist Didier Fassin (2012, p. 172) calls such explanations in humanitarian and development settings ‘culturalist’ arguments in which social facts are decontextualised and represented as timeless cultural traits – a way of thinking that bears resemblance to colonial ideas about racialised others as unmodern. Such ‘static models’ of culture also travel throughout health development thinking and policy.

The Global Political and Economic Context of the Safe Motherhood Initiative

The Safe Motherhood Initiative and the activities that it set in motion all took place in steadily worsening economic times, including Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) imposed by the World Bank starting in the 1980s that limited the proportion of government spending on health in already debt-ridden nations (Chorev, 2013; Kim et al., 2002; Keshavjee, 2014). This context, in combination with the ascendency of a neoliberal ideology (which I discuss below), undermined the implementation of a comprehensive PHC model and promoted a model of selective primary health care. The result was the promotion of TBA training, without simultaneously developing professionalised midwifery and strengthening health systems to deliver emergency obstetric care. This meant that health infrastructures that were inadequate before the SMI were still inadequate or worse – understaffed, under resourced, without emergency transport or services (Clark, 2016). How could TBAs be expected to ‘succeed’ in such conditions? The introduction of user fees for primary care services, including maternity care, stemming from the Bamako Initiative may also have encouraged women to continue to seek care from TBAs in the community rather than from trained providers in the formal healthcare system, and to delay referrals (Dzakpasu et al., 2014).

To the extent that politics and economics were understood as factors in the lack of progress in the reduction of the MMR during the first decade of the SMI, it was not in terms of structural violence – Paul Farmer’s adaptation of Johan Galtung’s term which links the deeply historical and politically created worldwide system of inequality and exploitation to real effects on health today in that it structures basic access to food, clean water and health care (Farmer, 2004; Galtung, 1969; Keshavjee, 2014). Rather, the role of politics was understood in terms of the narrower and more tractable idea of ‘political will’ to acknowledge the problem of maternal mortality and to prioritise and direct resources to it. Lack of political will certainly was a problem for the Safe Motherhood Initiative during the first decade of its existence (Horton, 2010) and efforts in this area have paid off as the profile of the issue has risen significantly and policy and funding commitments by world leaders and major philanthropic organisations have been greatly scaled up (MacDonald, 2019; Shiffman & Smith, 2007; McDougall, 2016; Storeng, 2010). Thus, the problem of political will was (and has been) more successfully tackled than the problem of politics writ large and historically deep. But without a view (and critical analysis) of the bigger picture it was much easier to conclude that TBAs were simply unable or unwilling to fulfil the roles set out for them by the SMI.

The first decade of the SMI also coincided with the HIV/AIDS pandemic across the global south. Because HIV-infected pregnant women are at increased risk of dying during pregnancy and the postpartum period (Calvert & Ronsmans, 2013; Lathrop et al., 2014), the pandemic took a direct toll on the MMR in many countries. Moreover, caring for HIV/AIDS-affected family members exhausted domestic finances and care networks within families and communities making them less able to direct care and resources to maternal health. The tremendous burden of HIV/AIDS that fell on already weak healthcare systems in turn hampered the care of pregnant and labouring women.

Despite the impact of these forces within communities and on nations struggling to reduce maternal mortality, they did not figure in the dominant narrative of the first decade of the SMI in general, nor on how the TBA component specifically had fared. For example, Barbara Kwast, a Dutch midwife and research scientist in the Maternal and Child Health unit of the WHO in the 1980s and 1990s (1993) mentions briefly the burden of the HIV epidemic on midwives as workers in her keynote address to the 1993 meeting of the ICM in Vancouver but does not address the direct or indirect impact of HIV/AIDS on the lives and deaths of pregnant women. The link between safe motherhood and HIV was sometimes noted (Starrs, 2006) and later commentators chided the global maternal health community for the lack of attention to this relationship (Mataka, 2007), but it did not figure prominently in the analysis of the SMI.

A New Humanitarian Logic with no Room for the Figure of the Traditional Birth Attendant

In the late 1990s, the Safe Motherhood movement underwent an internal reorganisation resulting in a new advocacy coalition and new set of donor partnerships including private corporations, bilateral aid organisations, universities and philanthropic foundations. Known as the Partnership for Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health, this new coalition was an expansion of the Inter Agency Group that had been in place since the launch of the SMI in 1987. The new Partnership diluted the authority of UN agencies, shifting some power to the private sector and made non-profit organisations responsive to a new set of expectations around evidence, programming and evaluation (McDougall, 2016; Storeng & Béhague, 2016). I have already spoken about the shift to the EBM paradigm in global health. In this section, I address how the rise in influence of private sector players through partnerships contributed to a distinct reframing of the problem of maternal mortality and its solutions in what may be described as ‘neoliberal terms’, that is, when the benefits of health and health care are understood in economic terms such that the goal of health is to enable citizens to optimise human productivity and economic development (Chorev, 2013). In the maternal health sector, the neoliberal turn in global health manifested in what I have called elsewhere the ‘economization of maternal survival’ (MacDonald, 2019, p. 266). Under this frame, the effort, time and money to address the problem of maternal mortality were argued as worthwhile not in terms of a moral response to human tragedy so much as an investment in the economic potential of women as individuals to contribute to their families, communities and nations (see also Murphy, 2017). Closely related to arguments about the importance of maternal health for economic development was the use of economic cost-effectiveness evidence to show that safe motherhood interventions were a good “global health buy” (Storeng & Behague, 2014, p. 10). As AbouZahr has commented in her review of the history of the SMI, to gain traction at the global level advocates had to tell ‘a story of progress’ (2001, p. 407). Traditional birth attendants, by their very name, were out of place in this reframing of maternal health as something that would be achieved by the modernisation of social policy and law and the transformation of women’s subjectivity. Indeed, they were a barrier to appeals for wider engagement that investing in maternal health was an investment in the future.

Lori McDougall (2016) has observed how the global maternal health community began to cohere around this new shared policy agenda in the early 2000s, manifestly visible in the tag line for the most influential women’s health and rights organisation in the world, Women Deliver: ‘Invest in Girls and Women. It pays’. Realising the need to appeal to political and policy leaders and private donors in new ways, the global maternal health community was strategic in taking up this ‘neoliberal turn’ in which individual and collective health would be achieved through economic growth rather than direct government interventions in social, health or education.

Just prior to this reconfiguration into the Partnership, the Inter-Agency Group had undergone another change which also impacted its stance on the TBA question. In 1999 the IAG had expanded to include for the first time two professional associations: the International Confederation of Midwives and the International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist (FIGO); representatives from both associations had been present at the Technical Consultation in Colombo in 1997 when the policy shift had been made. The vignette with which I opened this chapter reveals the tensions within midwifery as an internationalising profession at this time which played out in the TBA debate. On the one hand, midwives were relative latecomers to the global policy table; despite the fact that they comprise the vast majority of skilled maternity care providers in the world, the midwifery profession had not up to this point been a major global policy player (Varney et al., 2004; MacDonald, 2005). Nor had their skills been recognised as essential to the reduction of maternal mortality in the policy documents of the 1970s and 1980s (Kruske & Barclay, 2004). The struggle for professional legitimacy on the global stage and at the highest level of global policy – a thoroughly biomedical space (Chorev, 2013) – lay in tension with the critique of medicalised childbirth by midwives in many jurisdictions, but especially Canada, the US and New Zealand where midwives had mounted campaigns for direct entry into the profession and advocated the safety of home birth and other non-interventionist approaches which mainstream medicine tended to oppose (Bourgeault, 2006; MacDonald, 2007). This was the landscape of the debate about the inclusiveness of the term midwifery which broke out at the ICM in Vienna in 2002, when some midwives present insisted that all women who attend births are midwives and in contrast to the ICM and national midwifery associations positions which aligned with the high level policy making process and the skilled attendant policy. These changes to the make-up and priorities of the global maternal health advocacy coalitions are part of the broader context of the TBA policy shift.

Conclusion: The Return of the Traditional Birth Attendant?

Recently there have been calls for the ‘return of the traditional birth attendant’ in global maternal health, on the grounds that it makes practical and pragmatic sense not only as a last resort or stopgap measure when there is no trained or accessible personnel but also as a permanent feature of maternal health systems (Lane & Garrod, 2016; see also Byrne & Morgan, 2011; Prata et al., 2011). TBA-like providers are being re-positioned by such calls as part of the solution rather than as part of the problem and the range of tasks and roles (re)imagined for them is multiplying. Part of this conversation is being driven by research. The volume and disciplinary diversity of research on TBAs in terms of questions, methods and theoretical perspectives indicates that the evidence to evaluate the work of TBAs as part of health systems has been gaining traction over the last two decades even as TBAs were officially out of favour (See also Blanchard et al., 2019). Byrne and Morgan (2011), for example, have shown through a systematic review of the evidence that appropriate integration of traditional birth attendants within formal health systems as partners to skilled providers actually increases the use of skilled attendance rather than the other way around, as has often been asserted. Miller and Smith (2017) reviewed models by which TBAs can be partnered with skilled providers and attention be paid to local implementation factors required to ensure their success. TBAs did not disappear from communities with the policy shift to the skilled attendant, nor did research about them. Calls for their ‘return’ speak, in part, to the meaningful, evidence-based reintegration of TBAs into policy at the highest levels.

A key example of this policy return is the 2012 WHO guidelines on optimising health worker roles to improve access to key maternal and newborn health interventions. Known as the OptimizeMNH, these guidelines endeavour to tackle the issues of the global health worker crisis that are hampering improvements in rates of skilled attendance at births globally (WHO, 2012). Drawing on evidence that demonstrates their appropriate and effective utilisation of a number of skills normally reserved for higher level ‘skilled’ providers, such as the administration of misoprostol at births in the community for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage, the authors conclude that trained TBAs ‘can play an important role in improving maternal and newborn health’ (WHO, 2012, p. 9; see also Colvin, 2021).

Does the growing evidence base, and the authority it lends high level guidelines such as the OptimizeMNH, signal the end of policy ambivalence regarding TBAs? Yes and no. TBA bans remain in place in many jurisdictions, and the problems that have long plagued the potentially helpful work of TBAs – lack of meaningful training and integration, lack of respect, lack of remuneration – remain. But perhaps it is fair to say that global level maternal health policy on TBAs is no longer in retreat; it appears that the conversation is changing. For example, the OptimizeMNH guidelines contain a number of noteworthy recommendations and rationales, some of which relate to the critiques I have presented in this chapter. First, the OptimizeMNH document imagines the participation of TBAs not as a stopgap measure until the healthcare worker shortage can be rectified and health facilities everywhere can be adequately staffed and stocked. Rather it recommends changes in the distribution of biomedical authority in a way that makes room for the permanent inclusion of community level health workers who specialise in pregnancy and birth care or accompaniment – whether they are called TBAs or not – to perform an expanding number of skills that can improve and even save the lives of women in pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum. Second, we see in this document the language of equity in access to health care – an idea that was present in the original SMI that envisioned TBAs as providers who would extend and enable access to maternity care to underserved populations while maintaining safety (2012, p. 2). This idea has been held aloft in some significant corners of the scholarly debate about TBAs where the support and expansion of their roles has been described as an ‘ethical imperative’ in the absence of other options, and even in the presence of other options (Prata et al., 2011; Lane & Garrod, 2016).

It is also noteworthy that many of the skills being shifted to TBAs in these recommendations are enabled by another significant trend in global health: the new mandate for simple, high-impact and low-cost solutions that can function well in low resource settings. What anthropologist Tom Scott-Smith calls the ‘innovation movement’ (2016) in global health has given rise to many point-of-use technologies in reproductive and maternal health specifically, including portable hand-held ultrasound machines, anti-shock garments, cell phone apps to track antenatal care or screen for high blood pressure, and prefilled, single-use syringes for the delivery of long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) as well as new protocols that allow for the use of pharmaceuticals such as misoprostol by community-level providers. These developments are notable for the way that they push the normative boundaries of authoritative knowledge and practice in biomedicine – and go hand in hand with the task shifting policies brought by the WHO (2008, 2014, 2015a, b). The case of misoprostol use by community level providers is a prime example of how point of use biomedical technologies can support task shifting (MacDonald, 2020). Another example is the growing use of cell phones by TBAs within local maternal health projects which research is beginning to show can improve antenatal attendance and referrals (Martinez et al., 2018), strengthen healthcare systems (Labrique et al., 2020) and enhance the mutual respect between TBAs and skilled providers (MacDonald & Diallo, 2019) – the lack of which Miller and Smith (2017) identify as an implementation barrier. The role of new technologies is also evident in the new WHO ‘self-care’ agenda for sexual and reproductive health and rights – launched in June 2019 – which also involves a decentring of the facility and professional health provider as the sole locus of clinical care (WHO, 2019) and the promotion of more evidence-based interventions that can be utilised by community-level providers and women themselves. There is a certain irony that high-tech innovations have been catalysts for the re-engagement of TBA-like providers in the goal of improving maternal health, when in the past it was the perception of their inability or refusal to modernise that helped push them so low on the policy agenda. It is important to note, however, that despite the techno optimism involved in this trend, the balance between safe care and ‘self-care’ in maternal health will have to be carefully worked out. Relatedly, careful attention to the concomitant scale-up of, and the inter-relationships between, community and facility-based MNCH services is also needed (see McCoy et al., 2010, p. 91).

The policy space of global maternal health in which the TBA is being reimagined and deployed as an asset to global maternal health has been informed and animated by an array of shifting players, evidence and ideas as well as innovations in biomedical and communications technology. Many challenges remain. For example, even as estimates from the WHO suggest that community health workers (CHWs) in maternal health roles fulfil 17 trillion dollars’ worth of healthcare service a year, these workers are usually unpaid and often undervalued (Punjabi, 2019; see also Unnithan, 2021). Significant improvements in the delivery of maternal health care still needed in so many locales will not be realised by the return of the TBA, in any form, alone without health systems strengthening, a true reckoning with local context, greater understanding of and respect for women’s choices of care giver and place of birth, and equity in access to quality maternal health care everywhere.

Notes

- 1.

Sierra Leone, Ghana and Malawi are all jurisdictions in which TBA practice has been banned. In Uganda, the strong anti-TBA stance of the government emphasised in public speeches and documents has not been formally implemented, but the perception of a ban and news reporting around it has been the source of confusion and fear amongst TBAs, birthing women and healthcare providers (Rudrum, 2016).

- 2.

For a nuanced discussion of the uses of historical evidence in SMI advocacy, see Behague and Storeng, 2013.

- 3.

References

AbouZahr, C. (2001). Cautious champions: International agency efforts to get safe motherhood onto the Agenda. Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy, 17, 387–414.

AbouZahr, C. (2003). Safe motherhood a brief history of the global movement 1947–2002. British Medical Bulletin, 67, 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldg014

Adams, V. (Ed.) (2016). Metrics. What counts in global health. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Adegoke, A., & van den Broek, N. (2009). Skilled birth attendance-lessons learnt. BJOG, 116(Suppl. 1), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1009.02336.x

Allen, D. R. (1994). Managing motherhood managing risk. Fertility and danger in West Central Tanzania. University of Michigan Press.

Béhague, D., & Storeng, K. (2013). Pragmatic politics and epistemological diversity: The contested and authoritative uses of historical evidence in the Safe Motherhood Initiative. Evidence and Policy, 9(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1009.02336.x

Beihl, J. (2007). Will to live. AIDS therapies and the politics of survival. Princeton University Press.

Bergstrom, S., & Goodburn, E. (2001). The role of traditional birth attendants in the reduction of maternal mortality. In V. De Brouwere & W. Van Lerberghe (Eds.), Safe Motherhood Strategies, A Review of the Evidence (Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy, 17) (pp. 77–96). ITG Press.

Blanchard, A. K., Prost, A., & Houweling, T. A. J. (2019). Effects of community health worker interventions on socioeconomic inequities in maternal and newborn health in low-income and middle-income countries: A mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Global Health, 4, e001308. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001308

Bourgeault, I. L. (2006). Push! The struggle for Midwifery in Ontario. McGill-Queens University Press.

Byrne, A., & Morgan, A. (2011). How the integration of traditional birth attendants with formal health systems can increase skilled attendance. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 115, 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001308

Calvert, C., & Ronsmans, C. (2013). The contribution of HIV to pregnancy-related mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS, 27(10), 1631–1639. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAS.0B013e32835fd940

Campbell, O., & Graham, W. (2006). Strategies for reducing maternal mortality. Getting on with what works. Lancet, 368, 1284–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/50140-6736(06)69381-1

Campbell, O. M. R., Calvert, C., Testa, A. et al. (2016). The scale, scope, coverage, and capability of childbirth care. Lancet, 388(10056), 2193–2208.

Chorev, N. (2013). Restructuring neoliberalism at the World Health Organization. Review of International Political Economy, 20(4), 627–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2012.690774

Clark, J. (2016). The global push for institutional childbirths—In unhygienic facilities. BMJ, 352, i1473. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1473

Colvin, C. J. (2021). Making space for qualitative evidence in global maternal and child health policy-making. In L. J. Wallace, M. E. MacDonald, & K. T. Storeng (Eds.), Anthropologies of global maternal and reproductive health. Springer.

Cosminsky, S. (1977). Childbirth and Midwifery on a Guatemalan Finca. Medical Anthropology, 6(3), 69–04. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.1977.9965825

De Brouwere, V., Tonglet, R., & van Lerberghe, W. (1998). Strategies for reducing maternal mortality in developing countries: What can we learn from the history of the industrialized West? Trop Med Int Health, 3, 771–782. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00310.x

Dzakpasu, S., Powell-Jackson, T., & Campbell, O. M. R. (2014). Impact of user fees on maternal health service utilization and related health outcomes: A systematic review. Health Policy and Planning, 29(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czs142

Eades, C. A., Brace, C., Osei, L., & LaGuiardia, K. D. (1993). Traditional birth and maternal mortality in Ghana. Social Science and Medicine, 36, 1503–1507. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90392-H

Farmer, P. (2004). An anthropology of structural violence. Current Anthropology, 45(3), 305–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/382250

Fassin, D. (2012). Humanitarian Reason. A moral history of the present. University of California Press.

Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, peace, and peace research. Journal of Peace Research, 6, 167–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336900600301

Gilson, L. (Ed.). (2012). Health policy and systems research. A methodology reader. The World Health Organization.

Haruna, U., Kansanga, M. M., & Galaa, S. (2019). Examining the unresolved conundrum of Traditional Birth Attendants’ involvement in maternal and child health care delivery in Ghana. Health Care for Women International, 40(12), 1336–1354.

Horton, R. (2010). Maternal mortality: Surprise, hope, and urgent action. The Lancet, 375, 1581–1852. https://doi.org/10.1016/50140-6736(10)60547-8

International Confederation of Midwives. (2005). International definition of the midwife. International Confederation of Midwives.

Jordan, B. (1989). Cosmopolitan obstetrics: Some notes on the training of traditional midwives. Social Science and Medicine, 28(9), 925–937. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90317-1

Keshavjee, S. (2014). Blind Spot. How Neoliberalism infiltrated global health. University of California Press.

Kidney, E., et al. (2009). Systematic review of effect of community-level interventions to reduce maternal mortality. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 9, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-9-2

Kim, J. K., Gershman, J., Irwin, A., & Millen, J. V. (Eds.). (2002). Dying for growth. Global inequality and the health of the poor. Common Courage Press.

Kruske, S., & Barclay, L. (2004). Effect of shifting policies on traditional birth attendant training. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 49(4), 306–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/jmwh.2004.01.005

Kwast, B. (1993). Safe Motherhood – The first decade. Address to the International Confederation of Midwives Congress. Midwifery, 9, 105–123.

Labrique, A., Agarwal, S., Tamrat, T. et al. (2020). WHO Digital Health Guidelines: A milestone for global health. NPJ Digital Medicine, 3, 120. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-020-00330-2

Laderman, C. (1983). Wives and Midwives. University of California Press.

Lane, K., & Garrod, J. (2016). The return of the traditional birth attendant. Journal of Global Health, 6(2), 020302. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.06.020302

Lathrop, E., Jamieson, D., & Daniel, I. (2014). HIV and maternal mortality. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 127(2), 213–215. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.06.020302

Loudon, I. (1992). Death in childbirth: An international study of maternal care and maternal mortality, 1800–1950. Clarendon Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198229971.001.0001

MacCormack, C. (1989). Status and training of traditional Midwives. Social Science and Medicine, 28(9), 941–943. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(89)90322-5

MacDonald, M. (2005). Midwifery on the International stage: The Role of the International Confederation of Midwives in International Reproductive Health Initiatives. The International Workshop on Comparative Research on the Professions. McMaster University, April 29–30.

MacDonald, M. (2007). At work in the field of birth: Midwifery narratives of nature, tradition and home. Vanderbilt University Press.

MacDonald, M. (2017). Why ethnography matters in global health. Journal of Global Health, 7(2), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.07.020302

MacDonald, M. (2019). The Image World of Maternal Mortality: Visual economies of hope and aspiration in global campaigns to reduce maternal mortality. Humanity: A Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development, 10(2), 263–285. https://doi.org/10.1353/hum.2019.0013

MacDonald, M. (2020). Misoprostol: The life story of a life-saving drug. Science, Technology & Human Values. (1–26). https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243920916781

MacDonald, M., & Diallo, G. S. (2019). Socio cultural contextual factors of an health application to improve maternal health in Senegal. BMC Reproductive Health, 16, 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0800-z2017

Mangay Maglacas, A., & Simons (Eds.). (1986). The potential of the traditional birth attendant (WHO Offset publication no. 95). World Health Organization.

Martinez, B., et al. (2018). MHealth intervention to improve the continuum of maternal and perinatal care in rural Guatemala: A pragmatic, randomized controlled feasibility trial. Reproductive Health, 15, 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0554-z

Mataka, E. (2007). Maternal Health and HIV: Bridging the gap. The Lancet, 370(9595), 1290–1291. https://doi.org/10.1016/50140-6736(07)61552-9

McCoy, D., et al. (2010). Maternal, neonatal and child health interventions and services: Moving from knowledge of what works to systems that deliver. International Health, 2, 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inhe.2010.03.005

McDougall, L. (2016). Discourse, ideas and power in global health policy networks: Political attention for maternal and child health in the Millennium Development goals era. Globalization and Health, 12, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0157-9

Miller, T., & Smith, H. (2017). Establishing partnership with traditional birth attendants for improved maternal and newborn health: A review of factors influencing implementation. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17, 365.

Mohanty, C. T. (1991). Under Western eyes. Feminist scholarship and colonial discourse. In A. Russo & L. Torres (Eds.), Third World Women and the politics of Feminism (pp. 51–80). Indiana University Press.

Murigi, S., & Ford, L. (2010). Should Uganda ban traditional birth attendants? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/katine/katine-chronicles-blog/2010/mar/30/traditional-birth-attendants-ban. Accessed 29 Apr 2019.

Murphy, M. (2017). The Economization of Life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

O’Rourke, K. (1995). The effect of hospital staff training on management of obstetrical patients referred by traditional birth attendants. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 48(Suppl), S95–S102. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7292(95)02324

Olivier de Sardan, J. P., Diarra, A., & Moha, M. (2016). Travelling models and the challenge of pragmatic contexts and practical norms: The case of maternal health. Health Research Policy and Systems, 15(Suppl 1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-017-0213-9

Pigg, S. L. (1997). Authority in translation: Finding, knowing and naming traditional birth attendants in Nepal. In R. Davis-Floyd & C. Sargent (Eds.), Childbirth and authoritative knowledge (pp. 233–262). University of California Press.

Prata, N., Passano, P., Rowen, T., Bell, S., Walsh, J., & Potts, M. (2011). Where there are (Few) skilled birth attendants. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 29(2), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.3329/jhpn.v29i2.7812

Punjabi, R. (2019). Why governments should be paying community health workers. Time, (Oct 24).

Rudrum, S. (2016). TBAs in rural Northern Uganda: Policy, practice and ethics. Health Care for Women International, 37(2), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2015.1020539

Safe Motherhood Interagency Group. (2002). Skilled care during childbirth. Family Care International.

Sargent, C. (1989). Maternity, medicine, and power: Reproductive decisions in Urban Benin. University of California Press.

Scott-Smith, T. (2016). Humanitarian neophilia: The ‘innovation turn’ and its implications. Third World Quarterly, 37(12), 2229–2251. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2016.1176856

Sheikh, K., Gilson, L., Agyepong, I. A., Hanson, K., Ssengooba, F., & Bennett, S. (2011). Building the field of health policy and systems research: Framing the questions. PLoS Med, 8(8), e1001073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001073

Shiffman, J., & Smith, S. (2007). Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: A framework and case study of maternal mortality. The Lancet, 370, 1370–1379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61579-7

Sibley, L., & Sipe, T. A. (2006). Transition to skilled birth attendance: Is there a future role for trained traditional birth attendants? Journal of Health Population and Nutrition, 24(4), 472–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.009

Sibley, L., Sipe, T. A., & Koblinsky, M. (2004). Does traditional birth attendant training improve referral for women with obstetric complications? A review of the evidence. Social Science and Medicine, 59(8), 1757–1768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.009

Starrs, A. (1987). Preventing the tragedy of maternal deaths. A report on the international safe motherhood conference. World Bank, World Health Organization and United Nations Population Fund.

Starrs, A. (1997). The safe motherhood action Agenda: Priorities for the next decade. Family Care International and the Inter-Agency Group for Safe Motherhood.

Starrs, A. (2006). Safe motherhood initiative: 20 years and counting. Lancet, 368, 1130–1132. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69385-9

Storeng, K. (2010). Safe Motherhood: The making of a global health initiative. PhD Thesis London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Storeng, K., & Béhague, D. (2014). ‘Playing the numbers game.’ Evidence based advocacy and the technocratic narrowing of the safe motherhood initiative. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 28(2), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/maw.12072

Storeng, K., & Béhague, D. (2016). “Lives in the balance”: The politics of integration in the partnership for maternal, newborn and child health. Health Policy and Planning, 31, 992–1000. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czw023

Unnithan, M. (2021). Conflicted reproductive governance: The co-existence of rights-based approaches and Coercion in India’s family planning policies. In L. J. Wallace, M. E. MacDonald, & K. T. Storeng (Eds.), Anthropologies of global maternal and reproductive health. Springer.

Van Lerberghe, W., & De Brouwere, V. (2000). Of blind alleys and things that have worked: History’s lessons on reducing maternal mortality. Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy, 17, 7–34.

Varney, H., Kriebs, J. M., & Gegor, C. L. (Eds.) (2004). Varney’s Midwifery. Fourth Edition. Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Verderese, M., & Turnbull, L. (1975). The traditional birth attendant in maternal and child health and family planning: A guide to her training and utilization. World Health Organization.

Viisainen, K. (1992). Nicaraguan Midwives: The integration of indigenous practitioners into official health care. University of Helsinki Institute of Development Studies.

Walt, G., Lush, L., & Ogden, J. (2004). International organisations in transfer of infectious diseases: Iterative loops of adoption, adaptation, and marketing. Governance: International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, 17(2), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1110/j.1468-0491.2004.00243.x

Wendland, C. (2016). Estimating Death. A close reading of maternal mortality metrics in Malawi. In V. Adams (Ed.) Metrics. What counts in global health (p. 57–81). Duke University Press.

Whitaker, K. (2012). Is Sierra Leone right to ban traditional birth attendants? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2012/jan/17/traditional-birth-attendants-sierra-leone). Accessed 29 Apr 2019.

World Health Organization. (1978). Alma Ata Declaration. WHO.

World Health Organization. (1979). Traditional birth attendants: A field guide to their training, evaluation and articulation with health services (WHO offset publication 44). WHO.

World Health Organization. (1985). Report of the consultation on approaches for policy development for traditional health practitioners, including traditional birth attendants. WHO.

World Health Organization. (1994). Mother-baby package. Implementing safe motherhood in countries, a practical guide (Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Program. Division of Family Health). WHO.

World Health Organization. (2004). Making pregnancy safer: The critical role of the skilled attendant. A joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. WHO.

World Health Organization. (2005). The World Health Report: Making every mother and every child count. WHO.

World Health Organization. (2008). Task Shifting. Rational redistribution of task among health workforce teams. Global Recommendations and Guidelines. WHO.

World Health Organization. (2012). WHO Recommendations – Optimize MNH: Optimizing health worker roles for maternal and newborn health interventions through task shifting. WHO. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/77764/1/9789241504843_eng.pdf. Accessed 25 May 2015

World Health Organization. (2014). Using auxiliary nurse midwives to improve access to key maternal newborn health interventions. WHO.

World Health Organization. (2015a). WHO recommendation on partnership with traditional birth attendants (TBAs). WHO.

World Health Organization. (2015b). WHO recommendations on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health. WHO. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304983/. Accessed 20 Apr 2017.

World Health Organization. (2019). Self-Care Agenda, launching June 24 2019. https://www.bmj.com/selfcare-srhr. Accessed 7 June 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

MacDonald, M.E. (2022). The Place of Traditional Birth Attendants in Global Maternal Health: Policy Retreat, Ambivalence and Return. In: Wallace, L.J., MacDonald, M.E., Storeng, K.T. (eds) Anthropologies of Global Maternal and Reproductive Health. Global Maternal and Child Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84514-8_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84514-8_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-84513-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-84514-8

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)