Abstract

The adoption of the Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111) marked ILO’s first endorsement to universal non-discrimination and an early equal opportunity approach at work. Albeit considered to be premised upon “a traditional, formal-equality and formal-workplace vision of antidiscrimination law,” the convention marked a genuine new strand in international standard-setting in the Post-World War II and Philadelphia Declaration time. However, due to the implicit formal vision, it is assumed that ratification was more attractive and more feasible for countries of the Global North first. Following, this behavior diffused through colonial ties time-varying toward the Global South. Whether this assumption holds will also be studied regarding the moderating effects of networks of culture, trade, and regional proximity.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Anti-discrimination

- ILO (International Labour Organization)

- Philadelphia Declaration

- Labor law

- Diffusion

- Culture

- Trade

- Spatial proximity

Introduction

This chapter is a product of the research conducted in the Collaborative Research Center 1342 “Global Dynamics of Social Policy” at the University of Bremen. The center is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—project number 374666841—SFB 1342.

Labor law, especially in its origins as an initially domestic domain, developed in the context of, and in exchange and reaction to, developments in economic markets that required labor to produce their respective goods. These disputes did not always include the discernment that related negotiation processes should be or had to be embedded in a social–political framework. Labor law initially developed as individual law, which provided a contractual definition of rights and obligations within the framework of subordination between employee and employer. A collectivized understanding of the common interests and problems was a much later phenomenon and culminated in the emergence of collective labor law. It is no coincidence that the advent and heyday of collective labor law coincided with the nation-state-centered welfare state of the Golden Age of the 1960s and 1970s. It formed one of the dimensions of democratic self-determination based on national citizenship, which became a pillar in the interplay with the expansion of social welfare, of normative legitimacy, and of factual acceptance of democratic processes (Hurrelmann et al. 2007). Until today, the normative foundation and justification of either expansion and democratic legitimacy are the subject of constant renegotiation and renewal. However, these processes became increasingly decentralized and so power shifted to the international sphere—with a mixed summary to date in terms of advocacy, implementation, and effectiveness.

While the original idea of labor law was primarily the protection against economic disadvantages, impairments, and health hazards, it developed into a regulation of working life as a whole, mainly through the increasing involvement of collective actors and interest groups. In this process, the mutual integration with the prevailing social-political ideas began. In its historical development, labor law has thus not only experienced a horizontal differentiation but also a vertical one (Arthurs 2011, 21–22; Davidov 2011). Moreover, areas of regulation were now no longer only negotiated between national legislators (horizontal), but increasingly relocated to transnational and global contexts between states and under the organizational umbrella of international organizations (vertical).

Even if upheavals are on the horizon, the International Labour Organization (ILO) is still considered the central international organization for internationally agreed labor standards (Ebert 2015, 135; Helfer 2019) which must be implemented nationally. Its 102-year regulatory history has produced international labor standards that provide a comprehensive basis and framework for social policies. Their normative nature is not without controversy and has raised the question of the cultural foundations, assumptions, and (regional) ideas on which they are based, for whom they are easier or more difficult to implement and comply with, and what function they thus have in international concertation. On the contrary, it has been argued that over the last decades the ILO were not in a monopolistic position anymore (Chen 2021) on labor standard-setting, since a growing body of these standards has been nested into transnational labor standards such as free trade agreements, investment arrangements, policy documents of international financial institutions, and social missions of multinational corporations.

These remarks are based on the assumption that prior to these recent developments, the ILO was the sovereign body in the field of international labor standards. And while territoriality as a fundamental principle of labor law is widely uncontested (Mundlak 2009), developments in the context of globalization have raised new regulatory needs and demands, resulting in concepts such as ex- or deterritorialized forms of labor law. One of the consequences has been the increased international concertation and the massive expansion of labor regulation at the international and global levels.Footnote 1

The Discrimination (Employment and Occupation) Convention, 1958 (No. 111) (from now on referred to as C111) is particularly interesting in this context. The adoption of C111 marked the ILO’s first legally binding endorsement of nondiscrimination and an early equal opportunity approach at work. Although considered to be premised upon “a traditional, formal-equality and formal-workplace vision of antidiscrimination law” (Sheppard 2015, 249), the convention marked a genuine new strand in international standard-setting in the post-World War II and Philadelphia Declaration time. As a classic regulatory instrument, it was elevated to the status of a core labor standard in 1998 in the course of the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. These standards are not only subject to the usual ratification and national implementation procedures. Core labor standards apply universally to all members by virtue of their ILO membership. As a classic regulatory instrument at the international level, C111 thus retains the principle of territoriality (since the content of the regulations must be implemented nationally), while as a universal standard within the framework of the Declaration it becomes normatively valid in a deterritorializing manner.

The aim of this article is to first examine in principle if network specificities have influenced the ratification of C111. Like the other authors, I draw on the global network data that is used throughout this edited volume. These networks depict cultural similarity, colonial legacies, trade, and geographic proximity. Furthermore, the diffusion of international labor standards can have a homogenizing effect on national forms of labor regulation. However, there is also the question of the influence of already existing similarities between ratifying states. I will refer to this in a broader sense as, second, the influence of the national legal homogeneity in light of the territoriality of labor law. To map these national characteristics, I utilize a new national equality index that measures the de jure implementation status of national equality legislation. Further, the legal origin of a member, and the duration of membership in the ILO are considered.

While the general portfolio and history of ILO standards are now well studied, theory-based statistical analysis of their ratification history and diffusion along national characteristics are rare. To the author’s knowledge, studying the ratifications of an ILO convention as interaction processes in a network is both a novelty and the methodological aim of this chapter. I thereby contribute to the existing body of literature on the diffusion and ratification of ILO labor standards by adding a large-scale quantitative assessment through network analysis.

The chapter is structured as follows: In section “State of the Art: Transnational Antidiscrimination Law as a Tool to Provide Spaces and Vehicles to Challenge Domestic Labor Law’s Exclusion?”, I situate C111 in the field of transnational antidiscrimination law and in its interaction with national law. In section “Theorizing Transnational Diffusion Processes of International Labor Standards”, I discuss the state of the art in diffusion research of international labor rights, while in section “Data and Methods”, I present the underlying data construction and analysis methodology. Section “Results” presents the results of the network analysis and section “Conclusion” concludes the chapter.

State of the Art: Transnational Antidiscrimination Law as a Tool to Provide Spaces and Vehicles to Challenge Domestic Labor Law’s Exclusion?

The ILO’s standard-setting function has produced a vast number of international labor standards. In essence, transnational labor law (TLL), according to Blackett and Trebilcock (2015, 4):

has emerged to problematize and resist the direction of social regulation under globalization. Recognizing globalization’s asymmetries, and identifying spaces for action, TLL operates within, between and beyond states to construct counter-hegemonic alternatives. The field critically encompasses actions beyond the state, to take into account the actions of transnational enterprises, labour federations, civil society and other actors. Moreover, TLL does not stop where national labour law begins: the two are deeply intertwined and challenge each other. TLL is a form of multilevel governance, including the international, the regional, the national, and the shop floor: its ability to address challenges of economic interdependency is similarly enmeshed with its ability to acknowledge and deal with complexity, diversity and asymmetries across time and space—amongst states, across uneven regional development, amongst vastly differently empowered institutions and actors. TLL holds no monopoly on either the rise of legal centrism through the prevalence of “rule of law” doctrines, or the expansion of pluralist, reflexive new governance methods. Its distinctiveness lies in its capacity to be counter-hegemonic and promote social justice.

Blackett and Trebilcock emphasize further that “law’s normative character is indeterminate and must be the basis of continuous struggle for social justice, that is at the core of TLL’s emergence” (Blackett and Trebilcock 2015, 4). Indetermination and its inherent struggle are thus the basis and the result of the world society’s negotiation and agreement to develop the desired legal regulations, to endow them with binding force, and to implement them. As commonplace as it may sound at first, TLLs themselves are not a product of chance, nor is their dissemination (Chau et al. 2001; Baccini and Koenig-Archibugi 2014).

Universalization and the idea of equality were already conceived and named as fundamental and desirable in both the ILO Constitution of 1919 and in its Declaration of Philadelphia of 1944. However, they were only given concrete legal expression in two instruments in the post-war period: C100, with a clear reference to gender equality (“equal pay for work of equal value”) and C111 (Hepple 2009, 129).

C111’s core message is a universal idea of equal treatment and equal opportunities in employment and education, free from discriminatory practices based on race, color, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction, or social origin. Although the convention directly referred to the globally universalizing aims of the Declaration of Philadelphia in its preamble, it retained, however, a Global North and formal employment-prone loophole in allowing that “other special measures designed to meet the particular requirements of persons who, for reasons such as sex, age, disablement, family responsibilities or social or cultural status, are generally recognized to require special protection or assistance, shall not be deemed to be discrimination” (Art. 5. Para. 2). Even though the introduction of C100 and C111 made great steps toward the de jure acceptance and regularization of women’s work in particular (which had not been a matter of course until then), there was still no regulatory idea for the diverse forms that women’s work brought with it. This was and still is especially true for informal and nonstandard forms of employment (NSFE), even though they represented the dominant labor practice in the Global South. There was also a lack of framing regulatory ideas for the equitable distribution of care work between the genders and accompanying public support structures. Although C111 created the basis for a future holistic social policy concept, major questions of adequate, concrete implementation and embedding remained unanswered. It should also be noted that Afro-Asian countries used the process around the adoption of C111 to make the hitherto still existent differences in regulatory practices of the colonial labor regime between regular, mainly European workers and indigenous laborers more visible and to also condemn the colonial powers (Maul et al. 2019, 239). This was another result of the segmented regulatory world of work along the lines of unequal working conditions for women and men, as well as between colonial and noncolonial labor law regimes, which were also a corollary of ILO norm-setting at the time of C111’s creation.

In 1998, C111 entered the canon of the core labor standards. The elimination of discrimination with respect to employment and occupation (and within that C111) became one of the four constitutional principles as outlined in the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work of 1998. This altered its status. It is a core principle of the ILO Constitution that members may adopt and ratify conventions freely and without coercion. In turn, the core labor standards were chosen because they embody rights that are considered fundamental in the ILO Constitution. Consequently, regardless of ratification and level of development, ILO members are constitutionally obliged to respect and promote them.Footnote 2

As opposed to traditional labor law, which tries to focus on countering vertical inequality, C111 tackles horizontal inequality as part of antidiscrimination law (Sheppard 2015, 257):

Anti-discrimination law was historically limited to remedying horizontal inequality linked to group-based exclusions and disadvantages based on discrete grounds, such as race, national or ethnic origin, sex, disability, sexual orientation or religion. In contrast, labor laws primarily concerned with remedying social inequality and poverty based on the vertical inequalities between workers and employers. Labor law, with its focus on collective bargaining and employment standards in the formal labor market, too often excluded the concerns of marginalized workers who also tend to be members of the social groups traditionally protected by anti-discrimination law.

By virtue of its conception, C111 had the potential to be a tool “to provide spaces and vehicles” to counter domestic labor law’s exclusions.

Figure 8.1 shows the development of ratifications of C111 over time. Compared to the other diffusion processes in this volume, the ratifications of C111 are a more recent phenomenon. The Convention was adopted in 1958 and finally entered into force in 1960. The largest wave of ratifications took place between 1960 and 1980. This coincided with decolonization and the new or re-entry of numerous former, mainly African, colonies into the ILO, which also explains the large proportion of ratifications by countries in the Global South. Between 1981 and 2000, more sovereign members of the former Soviet Union and new members, especially from Asia, ratified. The third wave included mainly Central African and South Pacific countries, but also China. To date, 12 ILO members have not ratified the Convention.Footnote 3 Nevertheless, C111 is one of the best-ratified conventions in the ILO’s regulatory portfolio.

With its regulatory scope, C111 paved the way for the UN’s third generation of human rights: the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) were adopted in 1965 and 1979, respectively. It is often discussed to what extent the UN human rights conventions—to the detriment of the ILO’s C111—became necessary as “true” universal antidiscrimination instruments for strongly overlapping areas of regulation, since this convention, despite its universalist claim, primarily addressed workers in formal employment.

Theorizing Transnational Diffusion Processes of International Labor Standards

The transnational diffusion of international labor standards has so far been surprisingly undertheorized. This is probably due to the predominantly qualitative-comparative empirical share of mostly country studies on the interplay of ILO standards and national legal developments. To the author’s knowledge, no theorizing meta-studies have been done so far—probably because the academic debate on international labor standards is a complex interdisciplinary undertaking. It operates on the verge of organizational theory at the edge of international relations, organizational sociology, and political science as well as legal (history) approaches.

The interlinkage of the ILO’s internal governance structures with its resulting standard-setting processes has so far been studied quantitative-comparatively and predominantly in the framework of power dependence theory (Landelius 1965), neofunctionalism (Haas 1962, 2008 [1964]), and rational choice (Boockmann 2001).

Extended borrowings can be made from approaches in the field of norm diffusion within international organizations (Park 2006) and transnational idea and policy diffusion (Gilardi 2013). Although a specialized field, theoretical approaches of the legal scholarship related to the interaction of the different levels of labor law (Davidov 2011) and the interaction of the different implementation systems of international labor standards (Leary 1982) have been elaborated for much longer and in greater depth, making them relevant as well.

The International Relations scholarship has contributed largely through constructivist insights (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998). Park (2006) builds on their previous work and links an organizational identity that goes beyond former rationalist nation-state interests and the influence of intraorganizational norms that define appropriate behavior of actors within the international system and can thus explain norm diffusion success or failure. Her argument is hence that “the norms IOs espouse are the result not only of state power but of their socialization by non-state actors, and more specifically, by transnational advocacy networks” (Park 2006, 353). A more recent strand of post-functionalist research explains the structure of the policy portfolio of international organizations as a contingent functional and social outcome of the ongoing social negotiation processes of actors bargaining about the organizations’ internal governance in light of a common social structural framework (Hooghe et al. 2019). The strength of both approaches resides in explaining the approval of seemingly counterintuitive policy decisions by members. This is the case, for example, when members ratify conventions that initially appear to be disadvantageous for them in terms of their status quo.

According to Gilardi (2013, 454), there exists a scholarly consensus that diffusion can be defined as a consequence of interdependence. He refers more specifically to the work of Simmons, Dobbin, and Garrett who declared that “[i]nternational policy diffusion occurs when government policy decisions in a given country are systematically conditioned by prior policy choices made in other countries” (Gilardi 2013, 454). In line with Elkins and Simmons’ work, he adds that “the definition emphasizes diffusion as a process, as opposed to an outcome” and concludes that because of this, “diffusion is not equivalent to convergence. A significant increase in policy similarity across countries – a common definition of convergence […] – can, but need not, follow from diffusion. Even if it does, convergence characterizes the outcome of the process, but not the nature of the process itself” (Gilardi 2013, 454).

In drawing on his earlier work with Braun, he states that the underlying diffusion mechanisms are “systematic sets of statements that provide a plausible account of how policy choices in one country are systematically conditioned by prior policy choices made in other countries” (Gilardi 2013, 460). Furthermore, Gilardi subsumes that the scholarly consensus is that most mechanisms can be grouped into four broad categories, which the other authors of this book have also referred to: coercion, competition, learning, and emulation.

Coercion is the imposition of a policy by powerful international organizations or countries; competition means that countries influence one another because they try to attract economic resources; learning means that the experience of other countries can supply useful information on the likely consequences of a policy; and emulation means that the normative and socially constructed characteristics of policies matter more than their objective consequences. (Gilardi 2013, 461)

The diffusion processes examined below are understood and analyzed in terms of emulation. Finnemore and Sikkink (1998) have argued that norm diffusion processes involve the mechanism of emulation. This occurs in a three-step process: norm emergence, norm cascade, and norm internalization. In the first phase of norm emergence, new rules of appropriate behavior are brought to the tableau by norm entrepreneurs and with the help of internal support of the organization. It takes a critical mass of states, about one-third of the potential adopters according to Finnemore and Sikkink (1998, 901), who have been successfully convinced to recognize the new norm and to advance the dynamic toward the stage of norm cascade. In this second phase, norms are promoted in a socialization process by rewarding conformity and punishing noncompliance. In this phase, the reaction of the international community to their behavior is increasingly important to the member states. This can have a sensitive influence on their domestic legitimation and power. With the establishment and consolidation of this influence from the second phase, the process of norm integration has entered its final phase: the internalization stage. The norms are then so profoundly accepted that they are now taken for granted as the only possible type of accepted behavior. Gilardi has added another interesting outcome of this process which Finnemore and Sikkink themselves only indirectly address, which is that the burden of proof shifts over time:

In the early stages, it is the actors who wish to introduce women’s suffrage, smoking bans, or any other policy who need to demonstrate that these policies are needed, appropriate, and politically feasible. As the norm dynamic unfolds, the burden shifts to actors who do not want the policy to be introduced, who need to work harder to make their case than those who support it. Because norm dynamics lead to a change in dominant norms, once the new norm has taken over or is about to do so (around the tipping point in the “norm cascade”), the new rules become orthodox and the old heterodox, which shifts the balance of power between proponents and opponents. In other words, late in the process it is opponents, and no longer proponents, who need to engage in ‘norm contestation’. (Gilardi 2013, 467–468)

As was shown in the previous section, the evolution of C111 itself as well as the importance it was ascribed over time in the norm portfolio of the ILO is a perfect example of the three-stage emulation process of norm diffusion as presented by Finnemore and Sikkink.

Data and Methods

I attempt to explain the development of the ratifications of the ILO’s C111 by using a discrete time logistic regression with network effects of networks of geographical distances, global trade, cultural spheres, and colonial legacies as well as by the mediating influences of covariates. The latter reflects national specifics such as the legal origin and degree of integration into the intraorganizational context through the duration of membership in the ILO. The specificity of the dependent variable ratification of the C111 requires methodological adjustments to the original diffusion model as outlined in Chapter 1. These adaptations are succinctly sketched out below. Nevertheless, the analysis follows in essence the methodology detailed in Chapter 1 and thus contributes comparable findings to those of my colleagues from the other social policy fields in this volume on the global diffusion of international labor rights.

The assumed diffusion mechanism of contagion, according to which the probability of encountering to meet an “infected” and thus of “infecting” oneself increases over time as a result of increasing contact between subjects, also makes sense in principle for the study of ratification diffusion within international organizations. However, in comparison to the study of intergovernmental diffusion processes, this means an additional level of interaction (see Fig. 8.2), with its own intervening possibilities of contagion which must be methodologically considered and taken into account. On the one hand, a merely limited subgroup of all states that are together members of the organization (here the ILO) meet and can only infect each other within this framework. This is because ratifications of ILO conventions are only possible for and therefore restricted to ILO members. On the other hand, members of an organization are also members of the “world sample” of all existing and interacting states, thus in the original sense of the conceptualization of the networks used here according to Chapter 1. Organization members are not decoupled from world events outside the organization, but at the same time additionally determined by intra-organizational contagion processes. This means, for example, that colonialist influences can be given additional weight, as they can exert an effect both outside and inside the organization. Trade relations can also amplify existing extraorganizational imbalances within the organization. This is particularly the case when hegemonic extra-organizational inequality structures find a renewed reflection in the intraorganizational ones. However, these organizational structures also have the potential, at least in principle, to counter external hegemonic structures with alternatives through intraorganizational organization.

Conceptualizing this is not without risk of getting lost in the complexity of the processes that affect decision-making and opinion formation within organizations. For this reason, the covariates proposed here cover the three possible intervening levels with reference to individual member states only. They are not intended to control for individual country involvement in intraorganizational decision-making processes, which could also boost or mitigate ratification aspirations. In order to test for the influence of national characteristics, the legal origin and a newly created national de jure equality index were taken into account. To check on a generalized level for mediating influences of organizational membership, the duration of membership in the ILO was considered. Aspirations toward a respective regulation norm, which could motivate states to ratify conventions faster, are only taken into account insofar as the duration of membership can be understood as a proxy for a basic acceptance of the general organizational idea behind the ILO itself.

The original country sample of the networks presented by Mossig et al. (2021, in this volume) also has consequences for the sample of ILO members examined here. Of the 164 countries in the original risk set, three have never been members of the ILO: Bhutan, South Sudan, and Taiwan. They are therefore excluded in principle from the risk set, resulting in a total of 161 countries. The period covered spans from 1880 to 2010, meaning ratifications that took place after 2010 are not taken into account. This does not affect a lot of ratifications, thus the data is right censored. Another restriction of the networks weighs more heavily: the exclusion of states with less than 500,000 inhabitants from the networks. Especially in the last decades of ILO membership development, it is precisely and predominantly these states that have become new members. These members are therefore also not part of the risk set in the study presented here. Since this mainly concerns island states, the findings here are not relevant for them and there remains a residual risk that their influence is systematically underestimated. Further studies are needed on this. A total of 112 ILO members are thus included in the analysis.

C111 comes with a twofold determined temporality of its own compared to the other diffusion processes in this volume. The convention was adopted by the International Labour Conference in 1958 and entered into force in 1960, after the first two mandatory ratifications were registered. The analysis presented here therefore essentially refers to the period from 1958 to 2010. Furthermore, the time intervals with which time dependency as a result of unobserved heterogeneity in the piecewise constant step function is to be controlled were therefore adapted. Although they are oriented toward intraorganizationally important epochs, these are often connected with extra-organizational events. Table 8.1 gives an overview of the main ILO milestones and (UN) historical turning points relevant for the chosen periods which were taken into account for the analysis. The selection is based on the assumption that both key ILO declarations on the core issues of the Convention and relevant UN global political developments had an influence on the ratifications in the designated periods.

The data on the national ratification dates of C111 was taken from the new History of ILO Instruments Database (HILODB, Hahs 2021a), which will be published soon. A convention creates legal obligations qua ratification for the ratifying member. According to Article 19, 5(d) of the ILO Constitution, these are to “take such action as may be necessary to make effective the provisions” of a ratified Convention. This applies to both de jure and de facto implementation and transfer into national practice—such as court decisions, arbitration awards, or collective agreements alongside national laws.

The membership duration of the countries considered was calculated on the basis of data provided by the International Labour Organization (2020). It measures the duration of a country’s membership in the ILO at time t and is consequently a relative measure of the maturity of membership. I follow the results of Boockmann (2001) and assume that older, more “experienced” members are more susceptible to rapid self-induced ratification, while “younger” members become infected later after several contacts with those already infected.

I also control for the legal origin of a member country. La Porta et al. (2008, 287) classified countries’ legal systems based on the assumption that law and legal systems became transmitted as “bits of information” through channels such as trade, conquest, colonization, missionary work, migration, etc., from one country to another. Typically, legal transplantation took place between a few mother countries and the rest of the world. Drawing on the ongoing discussion in the legal scholarship, they distinguish between two main legal traditions (common law and civil law) and fine-tune their analysis to also cover subtraditions within civil law (French, German, socialist, and Scandinavian). According to Ahlering and Deakin (2005, 881–882), the influence of legal origin on the labor market is indirect:

[…] it is mediated through the practice of regulation, or ‘regulatory style.’ If a system has adopted a particular regulatory approach in one area, it is more likely to do so in another. In addition, the marginal cost of adopting the laws of the parent system are lower than attempting to begin anew with new methods and procedures. Thus ‘path dependence in the legal and regulatory styles emerges as an efficient adaptation to the previously transplanted legal infrastructure’ (Botero et al. 2004: 1346). Although no reference is made here to the concept of institutional complementarities, the same basic idea seems to be at work.

Chau et al. (2001, 129–130) subsume that the legal origin of a country can have an influence on the natural labor standard “(i) directly via the ideological bias it imposes on the relative importance of the state vis-à-vis the individual, and (ii) indirectly via its influence on the performance of government to protect the rights of individuals and government efficiency.” Therefore, institutional factors, which in turn are determined by the legal tradition of a country, could delay ratifications, even though one could have expected it based on the economic constitution of a country. It is not possible to address the full range of criticisms of the transferability of legal origin to labor rights within the scope of this chapter. As a representative example, Ahlering and Deakin’s (2005, 900–901) critique weighs particularly heavily, pointing to the sometimes large historical overlaps of regulatory logics in labor law and criticizing allegedly clear ideational path dependencies. It is largely on the basis of this critique that I have chosen to examine the relevance of legal origins for equality regulation.

Finally, the national equality index maps the annually averaged de jure strength value of national antidiscrimination law equivalent to the different dimensions of the ILO’sinternational antidiscrimination convention C111. It is calculated from six indicators of the WoL datasetFootnote 4 (Dingeldey et al. 2021), which quantify the dimensions of antidiscrimination considered in the C111. The values vary between 1 (“legally guaranteed”) and 0 (“no such guarantee exist”), with downward gradations indicating limited guarantees, weaker recommendations, or the non-inclusion and non-regulation of subareas of the antidiscrimination idea according to C111.

To sum up, the lack of available global diffusion data so far has severely limited the empirical and theoretical development of diffusion network effects as well as the development of a more profound understanding of contagion mechanisms in the field of transnational norm diffusion. Despite all its limitations, the analysis presented here is the most comprehensive to date with regard to the influence of networks on the ratification of an ILO convention (here: C111).

Results

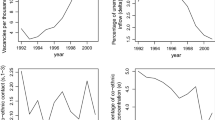

Figure 8.3 shows the development of the share of ratifiers per year and the cumulative ratifiers. Overall, a continuous and balanced increase can be seen. It is also clear that half of the ratifiers had already ratified by 1973. Visible increases occur once again in the early 1990s and from 1998 onwards. The critical mass of one-third of all ratifiers, i.e., the critical tipping point for the start of the norm cascade phase according to Finnemore and Sikkink (see section “Theorizing Transnational Diffusion Processes of International Labor Standards”), was reached within the first six years after the adoption of the convention. Since the number of ratifiers subsequently increases at an almost constant rate, no special effect can be observed here—at least descriptively—of the norm cascade phase which then theoretically follows and which rewards compliance and sanctions deviation. Attention should be drawn to the huge increase around 1960, lifting the share of ratifiers to 0.2. Since there was a large increase in membership in 1960, especially from former African colonies, this can be interpreted as an indicator that the underlying regulatory agenda of the convention was in the interest of both the new and the old members. I have pointed out before that through blaming, shaming, and condemnation, the process of drafting and adopting C111 was also used by hitherto still existing colonies to draw attention to the fact that, to their detriment, there existed a “colonial labor code” in parallel to the regular canon of ILO standards, the latter of which applied to other workers but excluded them.

The leaps around 1990 and 1998 then point to the two remaining phases. The second phase, the norm cascade phase, got a push in the early 1990s after a long period of continuous growth. As Table 8.1 shows several key elements such as declarations, world conferences on women, and the establishment of UN human rights conventions communicated the contents and ideas of the C111 to the world as a global social consensus and thus strengthened and promoted them.

Ratification was no longer only possible in principle nor solely the idea of a norm entrepreneur elite; instead, it became socially desirable in the structure of the international organization and increasingly binding by means of soft law. The internalization stage was reached at the latest by 1998, when the C111 was elevated to the status of a core labor convention and thus considered fundamentally binding in its regulatory idea for all ILO members, even without individual ratification. Antidiscrimination can now be regarded as something that is “taken for granted.” Moreover, what Gilardi called the reversal of the burden of justification has occurred: states must now officially justify why they do not adequately implement antidiscrimination rights.

A look at the share of ratifications of members classified according to the World Bank income categories in Table 8.2 also provides interesting insights. Boockmann’s (2001) econometric analysis of the duration between non-ratification and ratification of conventions hinged primarily on the implied costs of implementation for nonindustrialized countries. In industrialized countries, on the other hand, the preferences of central governmental actors were more decisive for the duration of ratification. But the cost argument cannot be easily accepted for C111.

The majority of low-income countries belong to the early ratifiers or the early majority. Surprisingly, almost half of the ILO’s high-income members (46.81%) are Laggards, Late Majority, or Non-Adopters. Vosko (2010) has comprehensively reviewed the long road that has been taken in the departure from the standard Western-oriented male-breadwinner employment relationship. It can only be assumed at this point that these effects are also reflected in the ratification behavior of the mainly Western-dominated high-income countries. Further research on this is needed elsewhere.

Table 8.3 shows the result of the discrete-time logistic hazard estimations in hazard ratios. Ratios larger than 1 can be interpreted as a positive relationship, while estimations between 0 and 1 indicate a negative relationship. The hazard ratios for the networks represent the odds of a member country ratifying C111 given the exposure through the network in question to countries that had already ratified C111. All models were calculated twice: Model 1 and Model 2 cover all 161 countries in the network sample for which data on legal origin and the national equality index were available. Models 3 and 4 refer to the smaller risk set of ILO members for which the same data were available. Thus, pure network effects could be examined (Models 1 and 2) and their significance compared with the results of the pure ILO sample (Models 3 and 4).

The assumptions from the descriptive observation with regard to the temporal development of ratifications are basically confirmed. Considering all baseline hazard rates together, there is an overall indication of a decreasing rate over time because these rates become smaller across time periods. But as interpreting time effects in these models is unusual, we will not go further into this. It is interesting, however, that a look at the other control variables shows that neither GDP per capita nor the democratization index is significant in any of the models. They do not play a relevant role in the diffusion process of the ratifications of C111. The fact that the cultural spheres network is not significant either fits the assumption that the convention was universally ratified by the most diverse member states. Overall, none of the networks examined have a significant influence across all models. Even the positively significant influence by the colonial legacies network on exposure becomes insignificant as soon as national covariates such as legal origin or the national equality index are included.Footnote 5 Only the spatial proximity network has a very high positive effect, which unexpectedly becomes insignificant when we restrict the network to only include ILO members for which data on national implementation of equality rights were also available. This is another strong piece of evidence that mainly national characteristics of the member countries explain the ratification behavior. Further, Mossig et al. (2021, in this volume) have already pointed out that geography should not be considered directly as a stand-alone effect but always in combination with other linked indicators. Only when either duration membership in the ILO, legal origin, the national equality index, or all national covariates together are taken into account (Models 2 and 4) does the exposure through the proximity network acquire its significant positive and strong influence. At the same time, the analysis of the national covariates is very insightful. For example, the country-specific national equality index is not significantly positive in the models when accounting for legal origin. The surprising result is that the national de jure status of national equality laws is not relevant for the exposure for ratification of C111. In principle, this speaks for the universal character of the convention, which should motivate countries to support the ideas of C111 through ratification, regardless of the level of development and implementation of equivalent standards at the national level. However, it contradicts the common narrative that countries ratify conventions primarily when the implementation costs for them are particularly low because they would not have to make major changes or adaptations to national laws, for example.

The strong effect of legal origins is unexpected. The reference category for the values shown were countries with German legal origins. Only a few countries in total belong to the Socialist legal origin and all of them in the sample have not ratified the convention, which explains the massive significant negative value for them. It is thus a methodological effect. The significant negative value for countries with UK/Common Law legal origin stands out in particular but is not significant. In contrast, the positively significant values for French and Scandinavian legal origin, both renowned homelands of early equality efforts and institutionalization, are unsurprising. It should also be remembered at this point that de jure data formed the basis of the analysis. These are and were not always congruent with the de facto situation. The probability of C111 compared to the probability of members with German legal origin is thus particularly high in countries with French legal origin and Scandinavian legal origin.

The duration membership in ILO shows a relatively small negative effect (close to 1). This indicates that if members do not adopt shortly after entry into ILO the chances of ratifying the convention later are reduced. Another explanation could be that older members are slower in ratifying—which was shown already in Table 8.2. This could therefore be a consequence of the norm cascade phase or even the internalization stage according to Finnemore and Sikkink: newer members need to prove themselves and since it has become part of the global norm to ratify C111, newer members never have a chance to NOT ratify.

The results update and confirm previous research. Chau et al. (2001) did not find any significant peer effects on the probability of ratification for C111. Nevertheless, they also identified the legal system as a relevant factor in the likelihood of ratification. While they considered this to be the only factor, the present analysis now shows that regional proximity and the duration of ILO membership are also relevant for the probability of ratification. Schmitt et al. (2015) reported strong empirical support for the existence of regional diffusion processes in relation to social protection and the introduction of social security programs. The probability that a country introduced a social security program increased if another country in the same geographical region had already adopted such a scheme. At the same time, they found a clear influence of ILO membership on adoption. Third, colonial dummies indicated clear effects that colonial heritage was important for consolidation. These last two effects cannot be confirmed for the probability of adopting the C111 antidiscrimination convention. Membership even has delaying effects on the ratification. And effects of colonial legacy network are not robust and significant across models to exert consolidating effects.

While for Chau the probability of ratification increases with time, this observation cannot be confirmed by the different networks. On the contrary, the controlled time periods showed a negative effect. The low impact of network effects further confirms Sheppard’s (2015) legal analysis and assessment that C111 was open enough for countries at different stages of their membership to ratify national levels of antidiscrimination standards.

Conclusion

This paper tested the influence of four networks on the diffusion of ratifications of C111 of the ILO. It was found that, with the exception of the geographical proximity network, the networks examined here do not play a significant role as a pipeline for diffusion. At the same time, the significance of the geographical proximity network can only be meaningfully interpreted in conjunction with other, in this case national, factors. The already weak influence of the colonial network also vanishes as soon as the national legal origin of the countries is included in the model. Despite legal origin, however, there is a proximity effect of the networks for which diffusion processes could be demonstrated, though the mechanism of this cannot be shown here. Further in-depth research is needed at this point.

The influence of ILO membership slows down the effect of ratification more than it supports it. Surprisingly, the influence of the national de jure status of antidiscrimination rights is completely irrelevant. This supports a decoupling of transnational and national regulation in the field of antidiscrimination rights and should be further investigated in terms of the de-territorialization of labor law. Referring to the question posed in the title of my contribution, this could indicate an initial but cautious “Yes, possibly from Geneva to the world.” To this end, it will also be relevant to quantitatively analyze the interaction of C111 and the UN human rights conventions ICERD and CEDAW—although the descriptive analysis for the two relevant periods after adoption indicates little remarkable increase in ILO C111 ratifications. Further analysis should also take into account spillover effects of the EU key directives in gender equality and nondiscrimination. This concerns questions of learning processes, for example between institutions with overlapping membership.

Overall, it must also be noted that domestic factors are mainly relevant for the likelihood of ratifying C111. However, diffusion mechanisms other than these are also conceivable, which could be revealed by, for example, further inclusion of states with populations below 500,000 inhabitants and expansion through historically deep data across all different networks.

Further work on the topic should for example consider the interaction effects of colonial legacy and legal origin in transnational antidiscrimination law. The strong negative effect of common law legal origin on the likelihood of ratification needs to be addressed in more depth. Similarly, it would be worthwhile to theorize the additional pipeline of IO membership alluded to in the article and then methodologically incorporate it into the model, for example, in the form of the UN, the ILO and the EU as networks in their own right. This would also come closest to the claim of examining diffusion not only in the form of convergence but also as a process of interaction.

Notes

- 1.

For a concise overview of the expansion of ILOinternational labour standards after World War II, see Hahs (2021b).

- 2.

The status of the Core Labour Standards also means a higher annual reporting cycle for each country that has not ratified one or more core conventions. For a comprehensive discussion of the systemic effect of the core labour standards on the ILO’s international labour rights regime, see Alston (2004) and the reply of Langille (2005).

- 3.

These are: Brunei Darussalam, Cook Islands, Japan, Malaysia, Marshall Islands, Myanmar, Oman, Palau, Singapore, Tonga, Tuvalu, United States of America (International Labour Organization2021).

- 4.

The indicators used are: e01 (“The law provides for equal opportunities for men and women in terms of access to employment”), e02 (“The law provides for regulation of positive discrimination [affirmative action/special measures] in order to overcome labour discrimination of women”), e03 (“The law provides for equal opportunities concerning ethnicity/race in terms of access to employment”), e04 (“The law provides for regulation of positive discrimination [affirmative action/special measures] in order to overcome labour discrimination of groups disadvantaged in terms of ethnic/racial backgrounds”), e06 (“The law provides for equal opportunities for men and women in terms of working conditions”), and e07 (“The law provides for equal opportunities in terms of working conditions concerning ethnicity/race”).

- 5.

In addition, all calculations were also checked with a non-normalized colony network. Here, the value for the proximity network becomes slightly larger, but overall no significant differences can be found based on the different modeling of the colony network. The non-normalized regression results are in the Appendix.

Literature

Ahlering, Beth A., and Simon Deakin. 2005. Labour Regulation, Corporate Governance and Legal Origin: A Case of Institutional Complementarity? University of Cambridge Centre for Business Research Working Paper No. 312, ECGI—Law Working Paper No. 72/2006. Brussels: ECGI.

Alston, Philip. 2004. “‘Core Labour Standards’ and the Transformation of the International Labour Rights Regime.” European Journal of International Law 15 (3): 457–521.

Arthurs, Harry. 2011. “Labour Law After Labour.” In The Idea of Labour Law, edited by Brian Langille and Guy Davidov, 13–29. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Baccini, Leonardo, and Mathias Koenig-Archibugi. 2014. “Why Do States Commit to International Labor Standards? Interdependent Ratification of Core ILO Conventions, 1948–2009.” World Politics 66 (3): 446–490.

Blackett, Adelle, and Anne Trebilcock. 2015. “Conceptualizing Transnational Labour Law.” In Research Handbook on Transnational Labour Law, edited by Adelle Blackett and Anne Trebilcock, 3–31. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Boockmann, Bernhard. 2001. “The Ratification of ILO Conventions: A Hazard Rate Analysis.” Economics and Politics 13 (3): 281–309.

Chau, Nancy H., Ravi Kanbur, Ann Harrison, and Peter Morici. 2001. “The Adoption of International Labor Standards Conventions: Who, When, and Why?” Brookings Trade Forum, 113–156.

Chen, Yifeng. 2021. “Proliferation of Transnational Labour Standards: The Role of the ILO.” In International Labour Organization and Global Social Governance, edited by Tarja Halonen and Ulla Liukkunen, 97–121. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Davidov, Guy. 2011. “Re-matching Labour Laws with Their Purpose.” In The Idea of Labour Law, edited by Brian Langille and Guy Davidov, 79–189. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dingeldey, Irene, Heiner Fechner, Jean-Yves Gerlitz, Jenny Hahs, and Ulrich Mückenberger. 2021. “Worlds of Labour: Introducing the Standard-Setting, Privileging and Equalising Typology as a Measure of Legal Segmentation in Labour Law.” Industrial Law Journal, dwab016.https://doi.org/10.1093/indlaw/dwab016.

Ebert, Franz Christian. 2015. “International Financial Institutions’ Approaches to Labour Law: The Case of the International Monetary Fund.” In Research Handbook on Transnational Labour Law, edited by Adelle Blackett and Anne Trebilcock, 124–137. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Finnemore, Martha, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change.” International Organization 52 (4): 887–917.

Gilardi, Fabrizio. 2013. “Transnational Diffusion: Norms, Ideas, and Policies.” In Handbook of International Relations, edited by Walter Carlsnaes, Thomas Risse, and Beth Simmons, 453–477. London: Sage.

Haas, Ernst B. 1962. “System and Process in the International Labor Organization: A Statistical Afterthought.” World Politics 14 (2): 322–352.

Haas, Ernst B. 2008 [1964]. Beyond the Nation-State: Functionalism and International Organization. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Hahs, Jenny. 2021a. Codebook of History of ILO Instruments Database (HILODB). SFB 1342 Technical Paper Series. Bremen: SFB1342.

Hahs, Jenny. 2021b. “The ILO beyond Philadelphia.” In International Impacts of Social Policy: Short Histories in a Global Perspective, edited by Frank Nullmeier, Delia González de Reufels, and Herbert Obinger. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Helfer, Laurence R. 2019. “The ILO at 100: Institutional Innovation in an Era of Populism.” AJIL Unbound 113: 396–401.

Hepple, Bob. 2009. “Equality at Work.” In The Transformation of Labour Law in Europe:A Comparative Study of 15 Countries, 1945–2004, edited by Bob A. Hepple and Bruno Veneziani, 129–164. Oxford: Hart.

Hooghe, Liesbet, Tobias Lenz, and Gary Marks. 2019. A Theory of International Organization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hurrelmann, Achim, Stephan Leibfried, Kerstin Martens, and Peter Mayer. 2007. “The Golden-Age Nation State and Its Transformation: A Framework for Analysis.” In Transforming the Golden-Age Nation State, edited by Achim Hurrelmann Hurrelmann, Stephan Leibfried, Kerstin Martens, and Peter Mayer, 1–23. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

International Labour Organization. 2009. Women’s Empowerment: 90 Years of ILO Action! Last accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.ilo.org/gender/Events/Campaign2008-2009/WCMS_104905/lang--en/index.htm.

International Labour Organization. 2020. NORMLEX. Information System on International Labour Standards. Country Profiles. Last accessed May 6, 2020. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11003:0.

International Labour Organization. 2021. NORMLEX. Ratifications of ILO conventions: Ratifications by Convention. Last accessed February 14, 2021. http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/de/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:11300:::NO:11300:P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:312256.

International Labour Organization. 03.02.2021. Timeline (Century Project—ILO’s History Project). Last accessed March 8, 2021. https://www.ilo.org/century/history/timelines/lang--en/index.htm.

La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. 2008. “The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins.” Journal of Economic Literature 46 (2): 285–332.

Landelius, Torsten. 1965. Workers, Employers and Governments: A Comparative Study of Delegations and Groups at the International Labour Conference 1919–1964. Stockholm.

Langille, Brian A. 2005. “Core Labour Rights—The True Story (Reply to Alston).” European Journal of International Law 16 (3): 409–437.

Leary, Virginia A. 1982. International Labour Conventions and National Law: the Effectiveness of the Automatic Incorporation of Treaties in National Legal Systems. The Hague: Nijhoff.

Maul, Daniel Roger, Luca Puddu, and Hakeem Ibikunle Tijani. 2019. “The International Labour Organization.” In General Labour History of Africa. Workers, Employers and Governments, 20th–21st Centuries, edited by Stefano Bellucci and Andreas Eckert, 223–264. Suffolk: Boydell & Brewer.

Mossig, Ivo, Michael Windzio, Fabian Besche-Truthe, and Helen Seitzer. 2021. “Networks of Global Social Policy Diffusion: The Effects of Culture, Economy, Colonial Legacies, and Geographic Proximity.” In Networks and Geographies of Global Social Policy Diffusion: Culture, Economy and Colonial Legacies, edited by Michael Windzio, Ivo Mossig, Fabian Besche-Truthe, and Helen Seitzer, introductory chapter of this volume. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mundlak, Guy. 2009. “De-territorializing Labor Law.” Law & Ethics of Human Rights 3 (2): 189–222.

Park, Susan. 2006. “Theorizing Norm Diffusion Within International Organizations.” International Politics 43 (3): 342–361.

Rogers, Everett M. 2003 [1962]. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

Schmitt, Carina, Hanna Lierse, Herbert Obinger, and Laura Seelkopf. 2015. “The Global Emergence of Social Protection: Explaining Social Security Legislation 1820–2013.” Politics and Society 43 (4): 503–524.

Sheppard, Colleen. 2015. “Inclusive Equality and New Approaches to Discrimination in Transnational Labour Law.” In Research Handbook on Transnational Labour Law, edited by Adelle Blackett and Anne Trebilcock, 247–259. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Vosko, Leah F. 2010. Managing the Margins: Gender, Citizenship, and the International Regulation of Precarious Employment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hahs, J. (2022). From Geneva to the World? Global Network Diffusion of Antidiscrimination Legislation in Employment and Occupation: The ILO’s C111. In: Windzio, M., Mossig, I., Besche-Truthe, F., Seitzer, H. (eds) Networks and Geographies of Global Social Policy Diffusion. Global Dynamics of Social Policy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83403-6_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83403-6_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-83402-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-83403-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)