Abstract

As of March 2020, educational institutions across Turkey were closed, and distance learning was introduced as an early precaution to halt the spread of the coronavirus. The shift was especially hard for K-12 school students, parents, and teachers, and it required collaboration between universities and schools more than ever. This chapter presents the systematic academic and psychological support provided by the Faculty of Educational Science of Bahçeşehir University, Turkey. Based on a needs analysis, faculty instructors offered online training and seminars to K-12 teachers mainly on digital literacy and integration of technology to courses, and to students and parents on topics such as anxiety, stress, and resilience. The support of faculty members to both public and private schools throughout Turkey has been proved to be of great importance in navigating through the pandemic, and especially in areas with low bandwidth and connectivity. One of the most important issues realized during the pandemic was the need for robust and continuous university-K-12 relationships to ensure continuity of teaching and learning in hard times.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

18.1 Introduction

After the first case of the COVID-19 was confirmed on March 11, educational institutions across Turkey were closed and distance learning was introduced as an early precaution to halt the spread of the virus. Shortly after schools were shut down, around 19 million K-12 students and one million teachers shifted to online education. Students at public schools received school lessons online and on TV through the Turkish Education Information Network (EBA) and public broadcaster TRT EBA, while those at private schools followed courses on the online platforms offered by their schools.

As of March 16, 2020, education at all universities was suspended as well, and universities determined their opportunities and capacity for distance education. A road map for distance education at universities was created by a delegation of concerned university experts. This road map focused on five primary topics: curriculum, infrastructure, human resources, content, and implementation. Bahçeşehir University (BAU) was one of the universities where decisions made about these topics were put into practice very rapidly and effectively due to the existing infrastructure and highly competent instructors. The instructors were used to giving online courses and were provided with ongoing training and support for such education.

BAU is a foundation (nonprofit and private) university that was established in 1998 with six campuses spread around Istanbul. The educational opportunities range from certificate programs offered on topics addressing the needs of people in various sectors to undergraduate and postgraduate degree programs in nine faculties with over 1350 lecturers and around 25,480 registered students, 4133 of whom are international students. BAU also offers cooperative education programs with 2330 CO-OP Brand Collaborations and 175 CO-OP Branded Courses, which are strongly supported by the business world.

The University is part of the BAU Global Education Network, as well as two chains of K-12 schools with around 180,000 students and 21,000 teachers in approximately 280 campuses all around Turkey. These schools, especially those in Istanbul, are in close contact with the Faculty of Educational Sciences. Within the “University within School” program, courses are linked to practice mainly through these K-12 schools under the supervision of the university supervisors and schoolteachers. In addition, collaboration with the Faculty of Education addresses the academic and psychosocial needs of the schools, covering a variety of subjects ranging from teacher training to curriculum development.

While distance education started rapidly in all departments of the university, the board of the university also discussed methods for supporting elementary and secondary schools during this unusual and challenging time. On the one hand, the government was trying to safeguard people from infection through a combination of confinement and mitigation strategies. There were ongoing lockdowns, particularly for people aged above 65 and below 20, and these disrupted the psychological life of not only people in these age groups but also that of the public. The serious threat the global pandemic posed to the psychological well-being of individuals along with its obvious health-related impact was felt increasingly in every layer of society. On the other hand, the shift to online education was a serious challenge; courses at the K-12 level that were designed for face-to-face education had to be transferred to online education. Neither students nor teachers and parents were ready for such a rapid shift.

As coronavirus hit the campuses, BAU, like other universities in Turkey and all over the world, set some priorities to respond to the quickly evolving situation: (1) maintaining health and safety of students, staff, and the community, (2) maximizing student learning and thriving, and (3) supporting staff. Educational reports came first from China and then from parts of Europe, along with formal and informal meetings of Turkish university members with the stakeholders of educational institutions. All reflected the fear, anxiety, and restlessness of the tri-pillars of the education system: students, teachers, and parents who were trying strategies to cope with the situation they were in. Thus, the university made the right decision by emphasizing that the health, safety, and well-being of every individual came first and that instructors had to operate with an understanding of the complexities in students’ home lives as well as mental, emotional, and physical strains their communities were facing. This message was explicitly shared by the board on a regular basis.

The Department of Psychological Counseling and Guidance (PCGD) in the Faculty of Educational Sciences took the lead in addressing the urgent needs regarding anxiety, fear, and loss of resilience by providing psychosocial support services, and frequently sharing information via television programs and online seminars first with the stakeholders of the university and then with the whole public. These programs, individual, and group, sessions helped students overcome the trauma the isolation might have caused them and their families. They were also much appreciated by the international students in particular, as well as those who had to return to their hometowns because of the closures. Feedback collected from the participants was very positive. Many said, “I learned what it means dealing with the unknown,” “Talking with a professional about the pandemic and the situation we are in made me feel relieved,” and “I was having so many bad scenarios in my mind especially when I was alone. Though they are not gone totally, I feel much better.” The experiences with the university members and students enabled the Faculty members to be better prepared to give support to K-12.

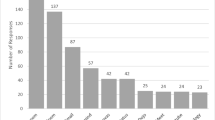

18.2 Initial Steps: Needs Analysis

At the beginning of April 2020, a comprehensive study was conducted by the Faculty of Educational Sciences to investigate the opinions of all stakeholders regarding distance education in general and the education provided in their institutions. The aim was to navigate the process of distance education and determine whether any support was needed to maintain the continuity and quality of the education provided. The Faculty hoped to address not only education at the time of the current school closure but also the possibility of future stoppages over the coming months due to potential recurring outbreaks. Research findings would help teachers and school leaders make informed decisions. The study was conducted at the beginning of April. Likert-type statements and open-ended questions were sent to schools in all regions through Google Docs. In only 5 days, 4435 primary school students, 9536 secondary school and high school students, 5661 teachers of 18 different subjects, and 25,436 parents responded to the surveys. Analyses of the data revealed that the schools did their best to maximize student learning and thriving. Delivering quality instruction, though it was clearly a challenge in current circumstances, was achieved to a great extent in the eyes of all stakeholders. With the help of technologically advanced systems and teachers with high digital literacy and competence in technology integration, the schools were able to offer synchronous and asynchronous online learning to students. Psychosocial support was offered to students and parents through school counseling departments, and the analyses of the data (open-ended questions completed by parents and teachers as well as talks with the heads of participating schools and many state schools) revealed the need for seminars and trainings on several issues for psychosocial and academic support. Thus, the data analyses showed that more collaboration and support on specific areas was needed, and that support was provided to schools in BAU Global Education Network as well as public schools all over Turkey.

18.2.1 Psychosocial Support

One of the main areas of need identified was resilience, defined as the ability to adapt when faced with stressors such as trauma, tragedy, threats, family and relationship problems, or serious health problems. The uncertainty the pandemic brought was challenging and worrying for everyone, yet it affected everyone differently. Psychological resilience was very important during the pandemic period. Heads of the K-12 schools asked BAU faculty members to inform teachers, students, and parents about the importance of psychological resilience during the pandemic period and guidance on how to improve their own psychological resilience. Similar requests came from Istanbul Provincial Health Directorate & Coronavirus Online Support Program (KORDEP) Working Group Volunteer Orientation and Training Programs. Many seminars on this issue were offered through social media live-broadcast, such as “Psychological resilience in children and adolescents in pandemic days,” “Psychoeducation and psychological first aid in pandemics,” “Protective role of resilience,” and “Training to explore our psychological resilience,” some of which reached around 3000 people. Because of the magnitude of the task, the instructors at the department collaborated with MA and PhD students, supervising the counseling the students provided in individual and group sessions, which was offered on a volunteer basis. Through Instagram accounts, sessions were offered on “Family resilience in pandemic days,” “The well-being of parents during the days of the pandemic,” and “Facilitating communication with children during pandemic days.” This ongoing project has reached around 4500 people so far.

Parent seminars focused on how parents should talk with students—especially young ones—about the pandemic, how to answer their questions, and how to balance personal and work life during the pandemic. In other seminars, topics such as the characteristics of stress, effects of misinformation on stress, and the importance of social relations/friendship were addressed.

Another issue that was of great importance to all stakeholders was anxiety: individuals felt helpless because they could not plan, predict, and control the events and situations in their lives (Barlow, 2000). The psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on children and college students were investigated (Hong et al., 2020; Radesky, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Both studies indicated that the COVID-19 death count showed a direct negative impact on general sleep quality, leading to stress and anxiety. Studies with adults who were living in different countries also showed high levels of anxiety and stress (Chakraborty & Chatterjee, 2020; Li et al., 2020; Madani et al., 2020; Mazza et al., 2020; Uvais et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). In addition, the scores for positive emotions and life satisfaction decreased (Li et al., 2020; Satici et al., 2020). A number of interactive online seminars were prepared jointly by the faculty members and K-12 Psychological Counseling and Guidance office, covering topics such as “Anxiety management between parent and child in coronavirus period.” Approximately 4500 people were reached with this seminar.

Another issue that led to anxiety among students and parents was the postponement of exams. In Turkey, many exams were postponed due to coronavirus. The university entrance exam, which has the highest expected attendance of 2,500,000 students, is just one example. There were some changes in the duration of the exam and the scoring, coupled with safety precautions expected from every single student and teacher. The exam anxiety experienced by the students increased dramatically not only because of the changes and additional procedures but also because of the lockdowns they had to obey. Thus, several seminars were carried out on this subject and all parties (students, teachers, and parents) were informed about strategies for decreasing anxiety and the importance of motivation. Many individual and group sessions were held for these purposes.

One strategy for dealing with the uncertainty and anxiety brought by the pandemic is to stay in the moment. The effectiveness of mindfulness practices on stress has been demonstrated in secondary school students, adolescents, and adult groups (Anand & Sharma, 2014; Baer et al., 2012; Carmody & Baer, 2008; Chandrasekara, 2018; Nyklícek & Kuijpers, 2008; Snippe et al., 2017). During the pandemic, many training and interviews were requested from our faculty to relieve the stress and anxiety of the stakeholders. Training included, “Mindfulness practices for children,” “Mindful parents and mindful children,” and “How can we use mindfulness skills when trying to normalize in the midst of this crisis?” Mindfulness seminars, which are regularly provided by the faculty within the “University within School” model, were given online to relieve the stress of the participants.

18.2.2 Academic Support

In addition to seminars on affective issues, the Faculty regularly informed parents about the importance of balanced screen time for children and how to spend the time they were all at home most effectively. Parents were facing a dilemma: on the one hand, they thought their children were spending too much time in front of screens, on the other hand, they wanted them to follow the online courses and not miss anything. Parents were given some tips to find out whether their children are actually conducting academic work or just “consuming.”

Furthermore, although teachers were provided with technology support by their own schools, faculty assistance was requested on strategies for redesigning education for online learning and ways of enriching synchronous and asynchronous lessons. The English Language Teaching Department held an online training, “Computer Technologies and Web 2.0 Tools during the Period of Distance Education,” for teachers working at state schools with the collaboration of the Ministry of Education (MoNE), and approximately 500 participants attended the training. The training addressed issues such as how to implement and use computer technologies effectively during the period of distance education and the preparation of course materials using Web 2.0 tools.

A very important finding of the study was that it underlined the importance of self-regulation in distance education. Self-regulated learning is a self-controlled process in which the learner manages their cognitive activities, emotions, motivation, and behavior to support the learning process (Zimmerman & Schunk, 2001). It was highly predictable that children who do not possess self-regulated learning skills, which includes setting goals, creating and implementing plans, and evaluating this process, were having difficulties in online learning environments. Online learning environments are different from those school settings in which learning activities are organized by teachers. Online learning provides the learners with the freedom to plan their own time, place, and learning activities. However, the effective use of this flexibility is directly related to the self-regulation skills of the learner (Barnard-Brak et al., 2010; Broadbent & Poon, 2015). Trainings were organized for both teachers and parents about self-regulation skills for achievement in online learning. The purpose of the teacher trainings was to explain the importance of self-regulated learning skills and to inform teachers on how to use online tools to develop learners’ self-regulation skills. In-class activities and home assignments intended to boost students’ self-regulation skills in online education were also shared with the teachers. The purpose of the parent training was to inform parents about what self-regulation skills are, why they are important, and what parents can do to support the development of these skills in their children. Parents were told that education might persist in the system in the form of several online classes, so they needed to understand the importance of students’ ability to regulate their own learning for their success.

As can be seen, all departments of the Faculty of Educational Sciences were involved in the initiatives to support K-12 schools, but the PCGD had the largest workload. All the seminars and trainings were done on a volunteer basis, as the mission of BAU includes supporting the community, fulfilling their needs while maintaining close contact with all sectors in the community, and preparing graduates according to community needs and demands. As for the Faculty of Educational Sciences, the collaboration between departments and K-12 schools has been of utmost importance both in terms of preparing teacher candidates and offering support to K-12 education and well-being.

Creating partnerships between universities and K-12 schools has always been essential for BAU. Researchers, instructors, and administrators have sought ways to boost student achievement by sharing expertise. However, it is more than an instructional relationship based on a one-way flow of information from the university to the schools. As exemplified before, the model “University within School” is based on the idea that partnerships develop in response to the needs identified by practicing teachers for their specific classrooms, curricula, and educational contexts. Accordingly, all the seminars by the instructors and all the practices by the university have been conducted to address the concerns and needs of collaborating schools. Theory and practice play an important role in determining the nature of educational research and teaching practice in teacher education programs. Thanks to practices in collaboration with K-12 schools, BAU could acknowledge the importance of theory in educational research and practice in teacher education and also ascertain the influence that theory has on practice in teacher education. We believe that strong and long-term partnerships between university faculty and K-12 schools are required and must be supported by grounding teacher education more strongly within practical contexts.

All initiatives are supported by the Innovative Education Development Research Center of BAU, which is an education, development, and quality center established for the purpose of determining, implementing, and improving the quality standards of schools. This center ensures that education standards that can be measured and supervised are established in schools. This center has organized most of the seminars, especially those provided to public schools.

18.3 Conclusion

The large-scale outbreak of the COVID-19 Pandemic has forced schools to suspend campus learning and switch to online learning practices. The shift imposed new challenges for institutions in implementing effective, engaging, and inclusive education. Our goal was to contribute to the development and improvement of the learners, teachers, and parents who are at the heart of the sudden change. Focusing on the changing roles of online teachers, we purposefully designed our practices according to the unique characteristics and needs of our target groups. To promote the development of effective online teaching practices and online learning processes, we supported them in a variety of ways, such as virtual seminars, online training programs, online discussions, and one-to-one support. Reflection and question and answer sessions were done after many of the seminars, which provided invaluable information about how to design future seminars and training to meet the needs and wants of stakeholders.

Looking back, we can identify several positive aspects of the initiatives taken. University and school collaboration, though not a new endeavor, became much stronger. In the research we conducted, K-12 teachers indicated that during this period they developed professionally. Through our collaborative endeavors, we could guide them in their design and teaching of online courses during that delicate time. We propose that the dynamics of online teaching are contextual and dependent upon various factors including the institutional resources, students’ goals, etc. To be able to promote the development of effective online courses, engaging learning environments, and a range of skills in teaching online, we designed our trainings and collaborations to be consistent with unique learning environments. Since the focus of professional development for online pedagogy suddenly shifted from integrating technology, in traditional teaching practices, to teaching through synchronous and asynchronous online tools, we attempted to extend the teaching and learning processes in online contexts by combining theory and practice at just the right time.

On the other hand, moving into online education posed difficulties not only for teachers but also for us. These challenges included workload issues, isolation problems, and differences in the educational contexts of teachers. The instructors at the Faculty had their own teaching workloads and were affected by the pandemic as well. Moreover, K-12 teachers were not competent at the same level with technological devices and synchronous/asynchronous learning environments. Building trust and sustainable inquiry during seminars, activities, etc. at the time of outbreak inevitably brought difficulties that had to be handled.

One of the most important issues COVID-19 has taught us is that it would be hard to sustain life—education, home life, family relations—without the collaboration and mutual support of institutions. The university and K-12 collaboration is an excellent example of this. BAU has done much to reach out to students, parents, and teachers in both private and public schools, and the initiatives will go on as they did before the times of the pandemic.

Measures of social distancing and quarantine did curtail the spread of the pathogen to a great extent, and we hope to mitigate the likely detrimental psychological effects through our collaborative endeavors.

References

Anand, U., & Sharma, M. P. (2014). Effectiveness of a mindfulness-based stress reduction program on stress and well-being in adolescents in a school setting. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(1), 17–22.

Baer, R. A., Carmody, J., & Hunsinger, M. (2012). Weekly change in mindfulness and perceived stress in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(7), 755.

Barlow, D. H. (2000). Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. American Psychologist, 55, 1247–1263.

Barnard-Brak, L., Paton, V. O., & Lan, W. Y. (2010). Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 11(1), 61–80.

Broadbent, J., & Poon, W. L. (2015). Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 1–13.

Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33.

Chakraborty, K., & Chatterjee, M. (2020). Psychological impact of Covid-19 pandemic on general population in West Bengal: A cross-sectional study. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(3), 266–272.

Chandrasekara, W. S. P. (2018). The effects of mindfulness based stress reduction intervention on depression, stress, mindfulness and life satisfaction in secondary school students in Sri Lankan. International Journal of Information, Business and Management, 10(4), 69–80.

Hong, Y. L., Cao, H., Leung, D. Y. P., & Mak, Y. W. (2020). The psychological impacts of a Covid-19 outbreak on college students in China: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 3933.

Li, S., Wang, Y., Xue, J., Zhao, N., & Zhu, T. (2020). The impact of Covid-19 epidemic declaration on psychological consequences: A study on active weibo users. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2032.

Madani, A., Boutebal, S. E., & Bryant, C. R. (2020). The psychological impact of confinement linked to the coronavirus epidemic Covid-19 in Algeria. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3604.

Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., & Roma, P. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among italian people during the Covid-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3165.

Nyklícek, I., & Kuijpers, K. F. (2008). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention on psychological well-being and quality of life: Is increased mindfulness indeed the mechanism? Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 35(3), 331–340.

Radesky, J. (2020). Supporting children’s mental health during Covid-19 school closures. NEJM Journal Watch Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine.

Satici, B., Gocet-Tekin, E., Deniz, M. E., & Satici, S. A. (2020). Adaptation of the fear of Covid-19 scale: Its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction., 8, 1–9.

Snippe, E., Dziak, J. J., Lanza, S. T., Nyklíček, I., & Wichers, M. (2017). The shape of change in perceived stress, negative affect, and stress sensitivity during mindfulness-based stress reduction. Mindfulness, 8(3), 728–736.

Uvais, N., Nalakath, M., Shihabudheen, P., Hafi, N. A., Rasmina, V., & Salman, C. (2020). Psychological distress during Covid-19 among malayalam-speaking indian expats in the middle east. Indian Journal of Public Health, 64(6), 249–250.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (Covid-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729.

Zhang, Y., Zhang, H., Ma, X., & Qian, D. (2020). Mental health problems during the Covid-19 pandemics and the mitigation effects of exercise: A longitudinal study of college students in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3722.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2001). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives. Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Atay, D. (2022). University-K-12 Collaboration During the Pandemic: The Case of Turkey. In: Reimers, F.M., Marmolejo, F.J. (eds) University and School Collaborations during a Pandemic. Knowledge Studies in Higher Education, vol 8. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82159-3_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82159-3_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-82158-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-82159-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)