Abstract

Management of haematology-oncology patients has historically been largely inpatient-based. With advances in the understanding of disease and improvements in supportive care, patients are increasingly being managed in the outpatient setting. This is especially evident in autologous stem cell transplantation, which is now routinely done as an outpatient procedure at various centres. As clinicians gain more experience in novel therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy and bispecific T cell engager (BiTE) therapy, these may potentially be administered in the outpatient setting in the near future with the adoption of a risk-stratified approach. Such a paradigm shift in the practice of haematology-oncology is inevitable and has been driven by several factors, including pressure from the institution/hospital to avoid unnecessary hospital admissions and for optimal use of inpatient resources to be more cost-effective and efficient. With favourable local regulations and funding, outpatient cancer care can be economically beneficial. The success of an outpatient cancer center is heavily dependent on planning the facility to be equipped with the appropriate infrastructure, together with the trained medical and supportive personnel in place. This, coupled with the utilization of emerging technology such as telemedicine, has the potential to revolutionize cancer care delivery in the outpatient setting.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Haematology and oncology departments have historically required inpatient ward beds for a large number of their treatments. There are many reasons for this, including the administration of complex and lengthy intravenous regimens and significant treatment-related toxicities such as emetogenicity, mucositis and infections. Over the last 20 years, however, there has been a move for selected patients to be managed in the outpatient setting, for both chemotherapy regimens and hematopoietic stem cell transplants (HSCTs). This has been done both during treatment and in the monitoring period following immediately afterwards. The outpatient environment ranges from the oncology office, outpatient hospital department, accommodation-based treatment facilities including hotels, to even the patients’ own homes.

This change has mostly been driven by several factors:

-

1.

Increasing pressure on the capacity of inpatient facilities and rationalization of inpatient beds

-

2.

Avoidance of unnecessary hospitalization

-

3.

Improvement in cost-efficiency

-

4.

Improvement of patient experience [1]

Several other additional factors have aided in the transition of cancer care to the outpatient setting. The availability of mobile infusion devices for chemotherapy, good supportive care and medications, as well as the development of targeted cancer therapies are just a few. In the United States, the push towards outpatient care was also aided by non-medical factors such as regulatory and economic ones – the Medicare Prescription Drug Improvement and Modernization Act of 2003 changing the calculus of infusion therapy reimbursements.

Outpatient care in haematology-oncology centres provide many benefits, including:

-

1.

Reducing the inpatient clinical load and alleviating pressure on constrained healthcare resources in order to optimize care delivery to high-acuity patients.

-

2.

Giving patients freedom from the hospital environment, providing families time together and allowing a degree of normality to remain. The ability to stay out of a hospital setting in a smaller, more comforting and familiar environment is often linked with higher patient satisfaction [2]. In addition, it also allows patients and caregivers to take back some control and become active members of the treatment team.

-

3.

Survivorship programs – transitioning to primary care providers so oncologists can spend more time with newly diagnosed patients

-

4.

Cost-effectiveness: Ambulatory care is recognized as a cost-saving initiative. Savings can be found in bed days [3] and staffing expenditure. A study at University College London Hospital [1] estimated that nurse staffing for their ambulatory care service cost approximately a third of that of the inpatient equivalent. It is important to emphasize that the amount of cost efficacy is heavily dependent on local regulations and reimbursement policies.

A multidisciplinary approach is crucial to the successful delivery of outpatient haematology and oncology care. A team of clinicians, pharmacists and nurses are just a few of many different disciplines crucial to the smooth running of an outpatient service. Ancillary services can also be offered in an outpatient setting, including nutrition and dietetics, physical therapy, psychological care as well as transitory services. Efforts should be made at planning level to coordinate seamless care in the ambulatory setting, focusing on synergy, access, synchronization and patient satisfaction.

Clinicians

Clinicians are crucial in identifying patients that may be appropriate for outpatient cancer care, as well as leveraging on their therapeutic relationship with the patient to encourage and educate them [4]. The primary oncologist plays a key role in coordinating and utilizing the various services that are available at each unique center.

Cancer is a complex condition that requires close cooperation with not just the primary oncologist, but several other disciplines as well. These typically include surgical specialties, radiation oncologists, infectious disease physicians and cardiologists. It is increasingly recognized that cancer patients have unique needs and disease profiles. With patients surviving longer and receiving increased numbers of lines of treatment, the types of complications experienced are also increasing. The role of multi-specialty clinics involving clinicians from various specialties is gaining in popularity as it can reduce the number of clinic visits a patient requires and also harmonizes care between the various disciplines.

Nursing and the Role of Advanced Practice Providers and Nurse Coordinators

It is impossible to overstate the role of nursing in an ambulatory cancer center. Oncology nurses are key to successful oncology care as they spend the most time with patients, playing the role of caregiver, educator, advocate and care coordinator. With the projected increase in oncology patient encounters expected to outpace that of anticipated resources, the ASCO Workforce Advisory Group has recommended improved integration of advanced practice providers (APPs) into the oncology workforce [5].

APPs can make significant contributions throughout a patient’s journey with cancer – from detection and diagnosis, through treatment, survivorship, surveillance and even end-of-life care [6]. Training to become a Nurse Practitioner (NP) helps develop the individual’s scientific foundation, leadership, quality improvement competencies, practice inquiry skills, technology and information literacy, policy competencies, health delivery system competencies, ethics competencies and independent practice competencies [7].

Besides the role of APPs , nurses also play an important role in their function as oncology nurse coordinators. As mentioned previously, cancer care is often complex and involves several moving parts that are centred around the patient. Key elements of a nurse coordinator’s role involve emotional support, guidance to patients, and coordination of the multifaceted aspects of the patient’s care [8].

Pharmacists, Drug Administration and Preparation

Pharmacists are essential to the running of any cancer center. Their role encompasses checking of prescriptions, drug preparation, and patient education. They play a major role in ensuring safe, effective and cost-effective drug therapy [9].

The availability of ambulatory delivery devices and hydration pumps is one of the key factors facilitating the move of so much inpatient clinical care to the ambulatory setting. These have enabled the ambulatory delivery of drugs such as ifosfamide and post-hydration for methotrexate regimens that were previously only administered on inpatient wards. The use of infusion pumps has enabled the ambulatory administration of regimens containing chemotherapy drugs typically given by continuous infusion (e.g. cisplatin in ESHAP) on an intermittent schedule (e.g. twice daily dosing), or those requiring continuous hydration fluid (e.g. ifosfamide or high-dose methotrexate-containing regimens). Several drugs previously administered intravenously were converted to oral administration to further facilitate outpatient administration. Specific examples include oral folinic acid and sodium bicarbonate for high-dose methotrexate regimens and oral mesna for oxazophosphorine-containing regimens, as well as antiemetics.

Optimal routes of outpatient drug administration need to be constantly evaluated to reduce chair times and ease of administration. Increasingly, several therapies are released in oral formulations, or may be able to be administered subcutaneously (e.g. CD20 monoclonal antibodies Rituximab for treatment of B cell lymphoma) rather than through prolonged intravenous infusions. This helps in optimizing chair usage and time spent for the patient.

Strategies that have been utilized to minimize wastage of chemotherapy drugs include

-

1.

Prepacked medications

-

2.

Dose banding

-

3.

Same day chemotherapy

Many drugs either use a flat dose or have traditionally been based on calculations of the patient’s body surface area (BSA). The use of BSA or other weight-based calculations for dosing of chemotherapy drugs have been controversial and may not be correlated with efficacy or toxicity. The advantages of dose banding and pre-packaging for more commonly used chemotherapy medications with longer drug stability can greatly reduce the time and manpower needed in the cancer center pharmacy to prepare them. A list of chemotherapy drugs that can be pre-packaged should be available in each outpatient pharmacy and referenced in the planning and organization of the centre’s processes [10].

Supportive Care for Chemotherapy or HSCT-Related Complications

Delivery of good supportive care for haematology-oncology patients and stem cell transplant recipients is vital in ambulatory care. Nursing and medical staff running ambulatory care centres must be equipped with the knowledge and experience in the management of chemotherapy complication. Improved antiemetic regimens now allow patients to avoid nausea and vomiting that require admission for intravenous hydration and antiemetics. Outpatient monitoring following chemotherapy during the neutropenic phase has been shown to be safe for many regimens, including for highly intensive protocols such as consolidation chemotherapy for acute leukaemias. HSCTs have also been given in either a mixed inpatient–outpatient setting, or entirely outpatient. The largest series of autografts reported have been Melphalan autografts for myeloma [11] and BEAM (Carmustine, Etoposide, Cytarabine and Melphalan) autografts for lymphoma [12], although many others have performed HSCT with reduced intensity conditioning or non-myeloablative regimens in outpatient settings as well [13].

Transfusion of blood products is also a common therapy that is administered in outpatient centres. An on-site blood transfusion service is most desirable for this purpose, although in the absence of one, this service can still be offered in collaboration with the blood transfusion service in closest proximity provided the appropriate safety and quality assurance measures are put in place.

Ancillary and Community Services

It is beneficial to an outpatient cancer center to provide ancillary services, although this will be dependent on the needs of the patient population each center serves. These services include physical therapy, nutrition and dietetics, and psychological services, amongst many others. A significant proportion of cancer patients can be malnourished and physically deconditioned from their illness [14], and can benefit greatly from having on-site services that address these needs. It is also estimated that about 32% of cancer patients are diagnosed with at least one mental disorder [15], supporting the need for psycho-oncology services.

In addition to on-site services, partnerships with local primary care providers and the setting up of satellite centres can also be explored. As an example , patients who require routine blood transfusions may be able to have this administered in a primary care or satellite center closer in proximity to their place of residence, rather than at the main cancer center. The same goes for procedures such as the flushing of lines , as well as blood tests. Medication delivery services could be explored for stable patients who do not require frequent physician reviews as this will also allow patients to maintain a normal life outside without spending too much time in a crowded clinic.

Planning for Outpatient Chemotherapy and Drug Delivery

Various models of delivering outpatient chemotherapy have been explored. The optimal model harmonizing physician appointments, blood tests, nursing services and chemotherapy administration needs to be unique to every center and the community it serves. For example, patients treated at a cancer center located in a busy urban community with well-connected infrastructure and transport will have different needs compared to those being treated in a regional center that may be more suitable for stable patients on maintenance therapies and do not require higher levels of nursing care.

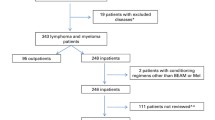

The organization of an outpatient chemotherapy center does not only involve the administration of the chemotherapy drug, but also the process – involving consultations, blood tests and drug preparation, and the resources – both human and technical. An example of a patient pathway for a chemotherapy session is illustrated in Fig. 4.1. However, it is important to note that not every patient follows the same pathway – for example, some patients require blood tests prior to chemotherapy while some do not. Liang et al. (2015) [16] have described three categories: (i) OC – Oncologist appointment and Chemotherapy, (ii) O – Oncologist appointment only, (iii) C – Chemotherapy only. Further refinement has been suggested by Lame et al. (2016) [10] by the addition of a further distinction – whether the patient requires blood tests, B – resulting in six categories of OC, BOC, O, BO, C, BC. Resources then need to be allocated to these categories, including but not limited to, nurses, phlebotomists, pharmacists, examination rooms and chemotherapy suites.

Patient pathway for outpatient chemotherapy with patient categories and resources. (Lamé et al. [10])

The backbone of outpatient chemotherapy administration is largely similar across most centres, although variations in its organization are common and unique to each center. Lame et al. (2016) [10] has outlined options for organizational variants in outpatient chemotherapy pertaining to the chronological order various aspects of the chemotherapy process is performed (Table 4.1) [10]. Whichever model a center chooses to adopt, it is imperative that the focus remains on maximizing resources and minimizing wastage, while optimizing patient care and enhancing the patient experience.

For example, Lau et al. (2014) [17] showed that patients preferred chemotherapy on the same day as their oncology outpatient appointments. However, not all chemotherapy regimens can be administered as such due to factors such as drug preparation time, or duration of administration. Soh et al. (2015) [18] attempted to circumvent this through pre-packaging of chemotherapy to improve patient waiting times for chemotherapy. However, experience in the Netherlands Cancer Institute shows up to 10% of patients with blood tests, and 5% of those without, were eventually deemed unfit for treatment [19]. The potential for drug wastage and accompanying financial costs for such a strategy cannot be underestimated, further emphasizing the need to strike a fine balance between resource planning and patient experience.

It is important for centres to continuously collect data and regularly review organizational policies. Lean healthcare practices should be encouraged, and advances in technology should be evaluated to further this aim [20]. As an example, mathematical modelling can improve scheduling [16], and the use of technology like radio frequency identification (RFID) can optimize chair use and the number of patients served [21].

Economical Advantages of Outpatient Care

The financial benefits of running an outpatient cancer center is heavily dependent on local regulations and funding. The benefits and shortfalls will be heterogenous across many states and countries so local regulations need to be carefully examined and approached appropriately. If possible, cooperation with local public officials should be sought to make outpatient care an attractive option for all the other non-financial benefits outlined in this chapter.

Clinical Trials

Great advances have been made in haematology-oncology in the past few decades, and increased understanding of the immunology and biology of cancer has led to the development of many therapeutics. Clinical trials are important in assessing the safety and efficacy of any treatment and form a cornerstone of cancer care. Consideration should be given to the setting up of an outpatient clinical trial center that is geared for the running of phase 1 or phase 2 trials. These services can aid with the recruitment of patients and monitoring of parameters such as pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies. They can either form part of the outpatient clinic, or set up as an independent unit, depending on the size of the center.

Telemedicine

Telemedicine utilizes telecommunication technology to deliver healthcare services, including consults and education. It is also a tool that allows for multidisciplinary discussion, including telepathology. Communities that benefit the most from the utilization of telemedicine are those in areas physically distant from the center in which they normally receive care. Telemedicine has been tested in multiple areas of medicine (not limited to oncological care) and has demonstrated high levels of satisfaction in both patients and physicians [22]. Several studies have also demonstrated improved cost efficacy with telemedicine [23]. Telemedicine can be used to complement traditional methods of patient care, from expanding access to specialist support, to education and patient support [24].

It should be stressed that telemedicine is not just using mobile apps like FaceTime™ or Zoom™ to engage with a patient, even if patients may request for consults to be conducted in this manner for the sake of convenience. It is imperative that whichever telemedicine platform is utilized (whether a program developed in-house or a commercial one), due care is taken to protect patient and data confidentiality and security. Telemedicine services can be approached in two main ways – synchronous or asynchronous formats. The former involves real-time engagement between the patient and his physician utilizing interactive video technology. The latter involves a “store-forward” approach where clinical data elements such as imaging, lab results, and video recordings can be stored to be interpreted at a later time [22]. Measures need to be put in place for a successful telemedicine service in order to achieve patient outcomes and satisfaction that is at least equivalent to in-person consultation.

Apart from conducting consultations with patients, telemedicine can be utilized in other ways to augment the patient care experience, for both patients and healthcare providers alike. The increased development of wearables that can aid in remote monitoring of patients’ vital signs may allow patients to be monitored at home for signs and symptoms of treatment-related complications such as fever [24]. Patient examination , with the exception of palpation, can also be performed with the right training and tools. Wound care, symptom management and even palliative care can also be administered using portable technology that can increase patient access to these services [22].

Telepathology is also an emerging technology that allows pathologists to remotely view microscopic images without being physically coupled to a microscope. The most discernible benefit thus far appears to be the accessibility to trained cytopathologists who are involved in rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) of tissue obtained from minimally invasive procedures where the tissue sufficiency is integral to accurate diagnosis. Traditionally, pathologists or cytotechnologists are required to be on-site where the procedures are being performed. This can tie up valuable manpower for an extended period of time especially if it is a particular challenging case. The use of synchronous, real-time telepathology services will enable more procedurists to have access to ROSE and improve the diagnostic yield of tissue obtained [22].

It is extremely important that the local regulations and infrastructure are supportive of telemedicine alternatives. Before embarking on a telemedicine program , centres should craft their program aiming to maximize the quality of patient care whilst minimizing the risks of liability for healthcare programs. Considerations include:

-

1.

Adequate training of the healthcare team and patient

-

2.

Indemnity/insurance coverage for telemedicine

-

3.

Whether the quality of information acquired during the teleconsult is adequate to formulate a diagnosis or treatment plan

-

4.

Potential limitations to assessment of the patient, such as

-

(a)

Inability of the medical team to perform a physical examination

-

(b)

Lack of visual and other cues compared to an in-person consultation

-

(c)

Technological limitations (e.g. transmission delay, potential for data breach) [25]

-

(a)

Limitations that are relevant to the treatment of the patient should be openly disclosed and discussed so that patients understand the risks before agreeing to receiving care through telemedicine. Should care providers feel that adequate assessment of the patient via telemedicine is not possible, they should always recommend that the patient be seen in person at a clinic or Emergency Department [25].

As with any consult, adequate documentation and patient privacy remain of utmost importance and should not be neglected. The healthcare team should also be aware that such consults can also be easily recorded by patients even if in-program recording functions are turned off. Regardless of an individual’s view on such surreptitious recordings, healthcare providers should be cognizant of the fact that these can be used as admissible evidence in future civil claims or disciplinary proceedings. It is prudent that the healthcare team continues to conduct themselves professionally on the assumption that every encounter is being recorded [25].

Technology has the potential to improve the patient experience and free up healthcare manpower to better optimize patient care. This can herald better multidisciplinary patient care, cost savings, increased patient access to treatment , clinical trials and education. With the appropriate focus on physician training, reimbursement and infrastructure development while addressing deficits inherent in the digital divide, telemedicine can be a powerful in the future of outpatient cancer care [23].

Outpatient Cancer Care in a Pandemic

The COVID19 Pandemic that began in early 2020 greatly impacted healthcare worldwide, not just cancer care. Apart from the obvious strain on healthcare resources, it has also had a significant impact on global economies and international travel. The COVID19 pandemic is not the first such disaster the world has faced, and will not be the last.

Considerations for cancer care that need to be undertaken in a pandemic are unique and aimed at addressing the negative effects it has on cancer treatment and research. Cancer patients and HSCT recipients are an especially vulnerable population who are at higher risks of complications from any pandemic illness and should take extra safety precautions. A retrospective analysis of 355 patients who died of COVID19 in Italy showed that 20% had active cancer [26]. Healthcare resource scarcity due to the influx of non-cancer patients into the healthcare system also disrupts the routine treatment of cancer and HSCT [27]. Serious and disruptive effects are also wrought upon the conduct of haematology and oncology clinical trials with reduction in recruitment, and delay in drug development timelines [28].

It is imperative during such pandemics that healthcare teams address the following issues:

-

1.

Which specific populations are most at risk

-

2.

Decisions for initiation or continuation of treatment, with careful balancing of risk/benefit

-

3.

Cancer patient prioritization by anticipated outcomes [28]

Specific to the COVID19 pandemic , measures undertaken in the outpatient setting include:

-

1.

Follow-up appointments by phone or telemedicine where possible

-

2.

Prioritize oral or subcutaneous routes of drug delivery over infusional routes

-

3.

Perform blood tests out of hospital

-

4.

Home delivery of medications and administration of infusional medications at home if possible

-

5.

Critical triaging of second opinions [28]

-

6.

Cryopreservation of donor stem cells or arranging alternative sources (e.g. cord blood) for HSCT

While every pandemic and wide-scale disaster will present its own unique challenges, it is important for haematology and oncology units to be as well prepared as possible for such eventualities through the gleaning of knowledge from prior experiences. The COVID19 pandemic of 2020 has shown how disastrous and deadly the lack of preparation can be for any healthcare system, cancer care notwithstanding.

References

Sive J, Ardeshna KM, Cheesman S, le Grange F, Morris S, Nicholas C, Peggs K, Statham P, Goldstone AH. Hotel-based ambulatory care for complex cancer patients: a review of the University College London Hospital experience. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(12):2397–404.

Joo E-H, Rha S-Y, Ahn JB, Kang H-Y. Economic and patient-reported outcomes of outpatient home-based versus inpatient hospital-based chemotherapy for patients with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2010;19(7):971–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0917-7.

Reid RM, Baran A, Friedberg JW, Phillips GL 2nd, Liesveld JL, Becker MW, Wedow L, Barr PM, Milner LA. Outpatient administration of BEAM conditioning prior to autologous stem cell transplantation for lymphoma is safe, feasible, and cost-effective. Cancer Med. 2016;5(11):3059–67.

Prip A, Møller KA, Nielsen DL, Jarden M, Olsen M-H, Danielsen AK. The patient–healthcare professional relationship and communication in the oncology outpatient setting. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(5):E11–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000533.

Towle EL, Barr TR, Hanley A, Kosty M, Williams S, Goldstein MA. Results of the ASCO study of collaborative practice arrangements. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(5):278–82. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2011.000385.

Reynolds RB, McCoy K. The role of Advanced Practice Providers in interdisciplinary oncology care in the United States. Chin Clin Oncol. 2016;5(3):44. https://doi.org/10.21037/cco.2016.05.01.

Williamson TS. The shift of oncology inpatient care to outpatient care: the challenge of retaining expert oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(2):186–9. https://doi.org/10.1188/08.CJON.186-189.

Monas L, Toren O, Uziely B, Chinitz D. The oncology nurse coordinator: role perceptions of staff members and nurse coordinators. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2017;6(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-017-0186-8.

Thoma J, Zelkó R, Hankó B. The need for community pharmacists in oncology outpatient care: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2016;38(4):855–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-016-0297-2.

Lamé G, Jouini O, Stal-Le Cardinal J. Outpatient chemotherapy planning: a literature review with insights from a case study. IIE Trans Healthc Syst Eng. 2016;6(3):127–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/19488300.2016.1189469.

Jagannath S, Vesole DH, Zhang M, et al. Feasibility and cost effectiveness of outpatient autotransplants in multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;20:445–50.

Seropian S, Nadkarni R, Jillella AP, et al. Neutropenic infections in 100 patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or Hodgkin’s disease treated with high-dose BEAM chemotherapy and peripheral blood progenitor cell transplant: out-patient treatment is a viable option. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;23:599–605.

McSweeney PA, Niederwieser D, Shizuru JA, Sandmaier BM, Molina AJ, Maloney DG, Chauncey TR, Gooley TA, Hegenbart U, Nash RA, Radich J, Wagner JL, Minor S, Appelbaum FR, Bensinger WI, Bryant E, Flowers ME, Georges GE, Grumet FC, Kiem HP, Torok-Storb B, Yu C, Blume KG, Storb RF. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in older patients with hematologic malignancies: replacing high-dose cytotoxic therapy with graft-versus-tumor effects. Blood. 2001;97(11):3390–400.

Trujillo EB, Claghorn K, Dixon SW, Hill EB, Braun A, Lipinski E, et al. Inadequate nutrition coverage in outpatient cancer centers: results of a national survey. J Oncol. 2019;2019(5):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7462940.

Mehnert A, Brahler E, Faller H, Harter M, Keller M, Schulz H, et al. Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(31):3540–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.0086. PMID: 25287821.

Liang B, Turkcan A, Ceyhan ME, Stuart K. Improvement of chemotherapy patient flow and scheduling in an outpatient oncology clinic. Int J Prod Res. 2015;53(24):7177–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2014.988891.

Lau PKH, Watson MJ, Hasani A. Patients prefer chemotherapy on the same day as their medical oncology outpatient appointment. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10(6):e380–4. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2014.001545.

Soh TIP, Tan YS, Hairom Z, Ibrahim M, Yao Y, Wong YP, et al. Improving wait times for elective chemotherapy through pre-preparation: a quality-improvement project at the National University Cancer Institute of Singapore. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(1):e89–94. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2014.000356.

Masselink IHJ, van der Mijden TLC, Litvak N, Vanberkel PT. Preparation of chemotherapy drugs: planning policy for reduced waiting times. Omega, Elsevier. 2012;40(2):181–7.

Coelho SM, Pinto CF, Calado RD, Silva MB. Process improvement in a cancer outpatient chemotherapy unit using lean healthcare. In: IFAC proceedings volumes, vol. 46. IFAC; 2015. p. 241–6. https://doi.org/10.3182/20130911-3-BR-3021.00047.

Lai L. Waiting time at National Cancer Centre reduced with RFID system. The Straits Times. 2013. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/waiting-time-at-national-cancer-centre-reduced-with-rfid-system.

Sirintrapun SJ, Lopez AM. Telemedicine in cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2018;38:540–5. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_200141.

Yunus F, Gray S, Fox KC, Allen JW, Sachdev J, Merkel M, et al. The impact of telemedicine in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15_suppl):e20508. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2009.27.15_suppl.e20508.

Wolfgang K. Telemedicine expands oncology care options. Oncol Times. 2019;41(8):13,19. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.COT.0000557852.06846.47.

En Ying K, Wei Munn M, Tee C, Hsu Hsien T. Covid-19 and issues facing the healthcare community: how can telemedicine help? April 23, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from https://www.allenandgledhill.com/sg/perspectives/articles/14781/sgkh-covid-19-and-issues-facing-the-healthcare-community-how-can-telemedicine-help.

Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4683.

Saini KS, de Las Heras B, de Castro J, Venkitaraman R, Poelman M, Srinivasan G, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer treatment and research. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(6):e432–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30123-X.

van de Haar J, Hoes LR, Coles CE, et al. Caring for patients with cancer in the COVID-19 era. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):665–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0874-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wu, I.Q., Lim, F.L.W.I., Koh, L.P. (2022). Outpatient Care. In: Aljurf, M., Majhail, N.S., Koh, M.B., Kharfan-Dabaja, M.A., Chao, N.J. (eds) The Comprehensive Cancer Center. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82052-7_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82052-7_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-82051-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-82052-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)