Abstract

The Philippine’s National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) aims primarily to build the adaptive capacity of local communities and increase the resilience of natural ecosystems to climate change to promote climate-risk resilience. Climate change is expected to have far-reaching impacts on the structure, ecological conditions, and functions of various ecosystems, diminishing their capacity to support people and communities. Thus, it is important to anticipate the conditions of a socio-ecological system considering climate change, and to maintain its integrity through adaptation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The Philippine’s National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP) aims primarily to build the adaptive capacity of local communities and increase the resilience of natural ecosystems to climate change to promote climate-risk resilience. Climate change is expected to have far-reaching impacts on the structure, ecological conditions, and functions of various ecosystems, diminishing their capacity to support people and communities. Thus, it is important to anticipate the conditions of a socio-ecological system considering climate change, and to maintain its integrity through adaptation.

The watershed approach, which uses the watershed as a planning unit and exemplifies a coordinated environmental management that focuses on public and private sector efforts (US EPA 2008), ensures a holistic method of managing ecosystems. Designing strategies to sustainably use and manage the resources in the watershed in view of changes in climate constitute an important step towards moderating the potential impacts of climate change and taking advantage of the opportunities that climate change presents. This also contributes towards building the resilience of the people and various ecosystems in the watershed.

In the Philippines, watershed areas are under the administration of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) and management is under the control of respective local government units (LGU). Nevertheless, watershed management entails collective action or a public involvement to influence collective action. This means different stakeholders, particularly in communities, mobilizing themselves for this common cause, or a public entity acting as a champion to pursue a common goal.

This paper presents the processes and lessons learned in developing a participatory climate change framework in two watersheds in the Philippines, namely Baroro Watershed and Saug Watershed. In the end, the project came up with a protocol on participatory climate change adaptation using watershed approach to enhance resilience of communities and ecosystems.

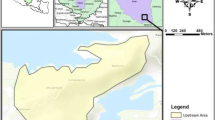

The Baroro Watershed is located in the northeastern part of the province of La Union and encompasses the municipalities of San Gabriel, San Juan, Bagulin, Bacnotan and Santol, and the city of San Fernando. It comprises a total of 19,486 hectares. The watershed is the main source of water for both irrigation and domestic purposes in all of the municipalities and city, except for Bagulin and Santol. Agriculture is the main source of income in the watershed.

The Saug Watershed, on the other hand, is located in the provinces of Davao del Norte and Compostela Valley. The watershed comprises the municipalities of Asuncion, Kapalong, New Corella and San Isidro and the city of Tagum in Davao del Norte, and the municipalities of Laak, Mawab, Monkayo, Montevista and Nabunturan in Compostela Valley. It has a total land area of 99,866 hectares, 60% of which is occupied by Davao del Norte and 40% by Compostela Valley. The watershed is an economically important catchment that hosts the agricultural production in the two provinces and supplies these areas with water, particularly the low-lying municipalities. Figure 2.1 shows the location of the two watersheds.

2 Planning for Resilience: An Integrated Approach

The complexity of the climate change problem demands an approach that would tackle its dynamic, multi-sectoral, multi-scalar and highly variable impacts. The risks and uncertainties associated with it also takes planning beyond the traditional ‘predict and act’ framework (Institute for Social and Environmental Transition-International (ISET) 2013), and strives for a system that is prepared for any disturbance or sudden change. Hence, national strategic plans for climate change and disasters envision resilience as the ultimate goal of all actions and efforts in response to these phenomena.

In 2013, ISET designed a Climate Resilience Framework (CRF) as part of measures intended to build resilience (Fig. 2.2). The framework emphasized that building resilience needs to occur in the context of a socio-ecological system so as to ensure that the dynamic interactions of different system elements and their feedbacks are considered. The CRF is a collaborative planning process based on understanding the vulnerability of the core components of a system – agents, institutions, and systems (left loop in Fig. 2.2) and strategic planning for climate change that highlights the resilient characteristics of each system component (right loop in Fig. 2.2), guided by an iterative learning approach that considers both local and scientific knowledge.

Capturing the concepts and principles of the ISET framework for building resilience, and considering also that managing climate and disaster-related risks benefit from an integrated approach rather than “separately managing individual types of risk or risk in particular locations” (IPCC 2012), a watershed approach was selected as the project framework for enhancing the resilience of communities and ecosystems in these project sites.

Using the watershed as a framework for planning not only provides a holistic approach that recognizes the linked social and ecological systems in a geographic unit, as well as its multifunctionality. This approach also benefits from “sound management techniques based on strong science and data” (US EPA 2008). From a mere hydrologic boundary from whence the concept was coined, it evolved to incorporate human use and economic values giving rise to Integrated Watershed Resource Management, which then expanded into a governance framework as encapsulated in the “watershed approach” (Cohen and Davidson 2011). US EPA (2008) defined watershed approach as an “environmental management that focuses public and private sector efforts to address the highest priority problems within hydrologically-defined geographic areas, taking into consideration both ground and surface water flow”.

The use of the watershed approach also benefits other aspects of watershed management, such as streamflow regulation, conservation of soil resources, enhancement of soil infiltration capacity, soil erosion minimization, optimum production of goods and services, eradication of upland poverty, and environmental stabilization (Cruz 1999), that contribute to improving the integrity of various ecosystems and strengthen their natural resilience to climate change and disasters.

3 Adaptation as a Process

Adaptation is defined as the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects. In human systems, it is the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate stimuli and its effects in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial benefits. In natural systems, it is the process of adjustment to actual climate and its effects; human intervention may facilitate adjustment to expected climate (IPCC 2014a).

Adaptation is implemented at various scales and levels, and its implementation differs depending on the context, such as resources, values and needs. Hence, the focus on adaptation as a process is important. However, current approaches to climate change adaptation prioritizes its technological and sectoral aspects, and little discussion is available on how it is practiced, as well as the impacts of adaptation strategies implemented (O’Brien and Hochachka 2010; IPCC 2014b).

Treating adaptation as a process, the project documented the steps it undertook to develop a protocol for participatory climate change adaptation. Following the principle that “all responses to climate change rely on information about risk and vulnerability” (IPCC 2012), the project conducted biophysical, socioeconomic, institutional, vulnerability and risk assessments that aimed to determine the current situation in the Baroro and Saug watersheds. The assessments relied on participatory rural appraisal techniques: spatial (fragmentation) analysis, water and greenhouse gas modeling; collection of secondary data for the watersheds’ biophysical characteristics; household surveys; and in-depth interviews of municipal/city officers.

Consistent with the watershed approach, communities living across the different gradients of the watershed (upstream, midstream and downstream) were selected as samples, particularly for the participatory rural appraisal techniques and household surveys. A key strategy of the project was to harvest the local knowledge of the communities and municipal officers through a historical situational analysis of the watershed. This narrative focused on the changes in specific ecosystem services: freshwater production; soil productivity; food, fiber and raw materials; maintenance and biodiversity; cultural services; and micro-climate. The process, together with other participatory techniques, served as an eye-opener to the communities on the challenges currently faced by the watershed, its impacts on them, and the acknowledgement that climate change could bring greater danger to their already fragile ecosystems.

Through several workshops and seminars, the results of the above activities were presented to the communities and the different watershed stakeholders. These venues served as sites for integration of local and scientific knowledge, as the project team also explained the biophysical and socioeconomic assessments based on the data gathered and computer modeling, and the leaders (mayors) in the municipalities and cities within the watershed shared their current programs and projects which concern the watershed.

Based on these assessments, both Baroro and Saug watersheds were found to be approaching critical ecological limit based on the significant degrees of fragmentation from 1988 to 2015, notably from agriculture and urban expansion. Both watersheds were also found to be highly at risk to flooding, which is aggravated by siltation of the river systems, and the Saug Watershed is also facing serious erosion problems. Institutions were also found to have limited knowledge on climate change and even the use of the watershed as a planning unit, hence the lack of coordination with other municipalities in implementing environment and disaster-related strategies. Such lack of coordination has the potential to result in conflicts among the municipal/city leaders.

With the knowledge of the current situation of the watersheds, a visioning exercise was performed among the various stakeholders to ascertain the desired situation that they would like to achieve for the watershed in the future. Strategies that would also lead to the attainment of the desired future were also identified in a workshop environment. These stakeholders crafted their visions and encapsulated their strategies in a ‘brand name’ that represents the values and opinions of the communities and stakeholders for the watershed.

After working with the community and the municipal government in the watersheds, the project team sought an audience with the members of the Provincial Councils in each of the watersheds. All of the findings on the status and condition of the watershed, including the ways forward that were desired by the communities and municipalities to attain the vision they crafted, were also presented. This activity, particularly in the case of Baroro Watershed, persuaded the provincial government to unite and mend the differences among the municipal/city leaders and act as one for the benefit of the integrity of the watershed and the local communities that depend on it. A Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) and Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) were also signed by the leaders in both Baroro and Saug watersheds, respectively, to institutionalize their commitment and support for the action plans and to promote resilience in the watershed in the face of environmental degradation and climate change. A seed fund was even earmarked for these activities in the Baroro Watershed by the Provincial Council.

The legal frameworks, as represented by the MOA and MOU, provided the basis for the different stakeholders at the community and municipal levels, including other relevant agencies, to craft an action plan for climate change adaptation. This details the strategies, potential sources of funds, responsible groups or stakeholders, and the timeline for implementation. A monitoring and evaluation system was developed to ensure that the objectives of the plans are satisfied, leading to the attainment of the vision for the watershed. Pilot communities were also identified to implement the plan, and it is expected that this would ripple to the other communities as their impacts become visible, finally leading to the scaling up of the approach.

4 Demystifying Participation

Developing an adaptation plan to be led and piloted by the communities is not an easy feat. Nevertheless, giving them the capacity for such task is an indispensable aspect of adaptation as communities are at the forefront of impacts, and therefore, of the actions to mitigate climate change.

Community participation, similar to adaptation, is also a process. It refers to the process in which individuals and communities engage in decisions about things that affect their lives (Burns et al. 2004). Community-based adaptation to climate change is characterized by the following (Dodman and Soltesova 2012):

-

Based on the premise that local communities have skills, experience, knowledge and networks to undertake locally appropriate activities to increase resilience;

-

Recognizes limits to/failure of planned, ‘top down’ approaches to adaptation;

-

Generates adaptation strategies through participatory processes involving local stakeholders—recognizes the need to include vulnerable people in decisions; and

-

Builds on existing cultural norms and addresses local development issues that underlie vulnerability.

Guided by the above principles, the project explored what it takes to have successful community participation in environmental or development projects. In a workshop environment, stakeholders, including community members, were asked to share projects that exemplified successful participatory approaches. Concepts that emerged from their narratives were highlighted and synthesized to form guidelines for participation that the project could implement.

In the Baroro Watershed, the concepts related to participation that emerged from the narratives included: different actors; participation of enablers (i.e., the LGU as represented by the mayor) and the influencers (selected community members who will first join the project); identification of different organizations that could provide support; knowledge enhancement that leads to the realization and acceptance of the problem; and integration of livelihoods. All of these were summed up into four principles: (1) setting up a framework to guide participatory action; (2) sustainable action through enabling policies and institutional arrangement; (3) capacity building and communication planning; and (4) innovative financing. Similar concepts emerged during the discussion with communities and stakeholders in the Saug Watershed, but with an emphasis on incentives and livelihoods.

The framework for participatory action represents who would champion the cause and the availability of willing community members who could demonstrate how the project operates, as well as the benefits that could be obtained from it. This framework emphasizes that community-based adaptation is not just a private act, but more often than not, a public, influence-based collective action. Enabling policies and institutional arrangements guarantee the permanence of the initiative, as well as the support across different levels of governance (i.e., provincial, city/municipal, barangay/community). This is where the dialogues with the Provincial Council and their seal of commitment as represented by MOA/MOU were instrumental. Hence, both bottom-up and top-down approaches were necessary to lend legitimacy and unanimity for a community-based project.

Integral to adaptation planning is the change in knowledge and values of the communities through awareness raising and capacity building. This enhances the adaptive capacity of the communities through better understanding of these phenomena affecting them. Their involvement in each level of the participation process also empowered them and made their voices heard in planning. Lastly, innovative financing, which should also consider the livelihood of residents and other incentives, represent the primary tangible benefits that makes participation more worthwhile for the communities.

All of the above should be encapsulated in a “brand” that the communities can rally behind, that represents the values that they can relate to, and the vision that they aspire to for the watershed. In the Baroro Watershed, they labeled the participatory climate change adaptation as “Ipon Ti Baroro Watershed”. This brand represents a fish that is endemic to the Baroro River with the same name, and which is an ecological indicator of the river ecosystem. Further, “ipon” also stands for unity (“pagtitipon” in Tagalog), and also connotes saving for the future. Meanwhile, the “branding” coined for Saug Watershed was the acronym SAUG, which stands for “sustainable approaches for unlimited goods and godly services”.

5 A Protocol for Participatory Climate Change Adaptation Using Watershed Approach

Based on the above activities, a protocol was developed that summarized the steps and achievements for enhancing participation in climate change adaptation using a watershed approach. It depicts, through the title, the framework used in the process (i.e., the watershed approach), the adaptation planning steps (Steps 1–7), and the cross-cutting principles on participation and capacity enhancement followed in its implementation (Fig. 2.3).

5.1 Biophysical and Socio-economic Assessment

This step was guided by a systems approach, i.e., the watershed approach, that was used to analyze the different biophysical (climate, land use, soil and geology, water, biodiversity) and socio-economic (population, livelihood, policies and institutions) components of the watershed, and how these affect ecosystem services in the watershed. The process relied on several assessment methodologies, such as, carbon stocks assessment, water modeling, fragmentation analysis, household surveys, historical situational analysis and key informant interviews. The design of methodology for this step is not limited to the above examples, but would depend on the goals of the adaptation project, particularly the ecosystem functions and services that require strengthening.

5.2 Participatory Risk and Institutional Capacity Assessment

Participatory risk assessment involved the identification of hazards and their probability of occurrence, impacts, and the effectiveness of current adaptation strategies. It is an investigative method that employs a variety of participatory tools to engage local stakeholders in their own climate change-risk and vulnerability diagnosis. The institutional capacity assessment, on the other hand, guided by the elements of resilient institutions in the ISET framework, determined the access rights and entitlements, information flows, application of new knowledge, decision-making processes, as well as the capacity to anticipate risk, capacity to respond, and capacity to recover and change, of the different institutions in the watershed.

Included under this step is the participatory scenario development, which explored the future with the communities and other stakeholders in a creative and policy-relevant way. Given the current risks and impacts of climate-related events, the results of climate, water, and carbon stock modeling were presented, and this provided planners with a glimpse of what they should consider when developing planning frameworks.

5.3 Visioning

A vision represents the future that the stakeholders would like to achieve for themselves and the watershed. In a workshop environment, participants were asked to discuss how they wanted to see the watershed in the future and to write these visions on metacards (one item per metacard). All metacards were collected and similar responses were grouped. The top responses were placed together and used to create a vision statement, which was further refined by the participants until they reached a consensus.

The vision statements developed for the Baroro and Saug watersheds are as follows:

-

Baroro Watershed – We envision the Baroro Watershed to be a sustainable and climate-resilient source of water, capable of providing a sufficient livelihood, and an ecotourism destination in La Union.

-

Saug Watershed – A well-managed, climate-resilient Saug watershed sustaining multiple uses of goods and services for its constituents through science-based approaches and local participation.

5.4 Strategy Building

Strategy building refers to the actual strategies formulated by different stakeholders to respond to issues and problems identified in the assessment, considering future climate change and progress towards achieving the vision that they aspire to achieve. Strategies were identified per sector or ecosystem, and, considering the watershed gradient (upstream, mid-stream and downstream), were consolidated for consistency.

5.5 Action Planning

Action planning, following the legal framework emanating from the provincial government, entailed the detailed community-based adaptation planning for the different pilot communities. At this stage, commitment was already secured from different stakeholders, particularly the communities, to effectively implement the proposed action plan. Potential sources of funds are also identified. In the case of Baroro Watershed, part of the MOA stipulated seed funding for this initiative.

Some important strategies identified for the pilot communities were reforestation using native species, organic farming, regulation of harmful agricultural inputs, fish pen regulation, alternative livelihood creation, and solid waste management. This action plan is encapsulated in a “brand” that represents the overall values and objectives of the initiative.

5.6 Implementation (Piloting and Scaling Up)

Implementation included setting up of a pilot barangay or community for each watershed site to implement the participatory climate change adaptation. It requires the recognition and assistance of the LGU to ensure that the barangay has a legal identity, availability of resources, and to secure guarantees for the continuity. An organization structure and specific work plan were laid out, including the Monitoring and Evaluation System, to guide the implementation of the adaptation project. This part, however, was not covered by the project. Nevertheless, mechanisms were installed to regularly assess the status/progress of the community-based adaptation, as well as plans for potential scaling up.

5.7 Monitoring and Evaluation

Indicators for monitoring and evaluating the participatory community-based adaptation were developed from parameters measured before the project. This would then be compared to the future status of the watershed following implementation of the project. The indicators included: stream discharge, meteorological (rainfall and temperature), soil moisture, water use efficiency, biodiversity and ecosystems, water balance, and socioeconomic characteristics. Scale-appropriate indicators for the communities were also developed, and this would also be implemented using participatory approaches.

6 Lessons Learned

The project succeeded in formulating a protocol for participatory community-based adaptation using a watershed approach. This protocol contained the critical know-how in climate change adaptation and watershed management, particularly in improving the integrity of the ecosystems and ensuring the continuity of the goods and services that they provide for the welfare of the people.

The following are the lessons learned in the process of formulating the protocol:

-

Continuing ecosystems degradation increases communities’ risks and vulnerability to climate-induced hazards and disasters and undermines their resiliency.

-

Recognizing the different scales of adaptation through the watershed approach (communities, municipal, and provincial levels) should consider each group’s role —i.e., the context of their adaptation (values, resources, and needs).

-

A participatory framework, such as that described above, is important for catalyzing collective action among stakeholders to enhance climate change adaptation.

-

Solutions-based analysis that incorporates local knowledge will empower the community to be more mindful, prepared and proactive in addressing the potential negative impacts of climate change acting on their person, their livelihood and the environment.

-

Recognizing the roles of communities in watershed management positively affects their status and stimulates their creativity in crafting adaptation strategies that are effective and bring about rehabilitation.

-

Local stakeholders need recognition and assistance from LGUs, national agencies and other organizations to enable them to perform as effective watershed stewards.

-

Local communities are willing to participate in implementing adaptation strategies that will conserve watersheds as well as their livelihoods.

-

Lastly, community-based adaptation in the context of participatory watershed management cannot operate solely at the local level; it needs to be effectively linked to the higher scales of governance in order to enhance the resilience of communities and ecosystems.

References

Burns D, Heywood F, Taylor M, Wilde P, Wilson M (2004) Making community participation meaningful: a handbook for development and assessment. The Policy Press, Bristol. Retrieved from URL: https://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/default/files/jrf/migrated/files/jr163-community-participation-development.pdf

Cohen A, Davidson S (2011) The watershed approach: challenges, antecedents, and the transition from technical too to governance unit. Water Altern 4(1): 1–14. Retrieved from URL: http://www.water-alternatives.org/index.php/allabs/123-a4-1-1/file

Cruz RVO (1999) Integrated land use planning and sustainable watershed management. J Philippine Dev, Number 47 26(1) First Semester 1999. Retrieved from URL: https://dirp3.pids.gov.ph/ris/pjd/pidsjpd99-1land.pdf

Dodman D, Soltesova K (2012) Community-based adaptation in urban areas: potential and limits. Paper presented during the Third Global Forum on Urban Resilience and Adaptation. Session D1: Mitigating and adapting from the bottom up: community-based solutions. Retrieved from URL: https://www.slurc.org/uploads/1/0/9/7/109761391/dodman_-_cba_potential_and_limits.pdf

Institute for Social and Environmental Transition (ISET) – International (2013) Climate resilience framework: putting resilience into practice. ISET-International, Boulder, 22 p

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2012) Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation. In: Field CB, Barros V, Stocker TF, Qin D, Dokken DJ, Ebi KL, Mastrandrea MD, Mach KJ, Plattner G-K, Allen SK, Tignor M, Midgley PM (eds) A special report of working groups I and II of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK/New York, NY, p 582

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014a) Annex II: Glossary. Climate change 2014. Mach KJ, Planton S, von Stechow C (eds) Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [Core Writing Team, RK Pachauri and LA Meyer (eds)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, pp 117–130

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2014b) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability–summary for policymakers. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Billir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genva RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracket S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL (eds) World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 34. pp

O’Brien K, Hochachka G (2010) Integral adaptation to climate change. J Integral Theory Pract 5(1):89–102

PROVIA (2013) PROVIA guidance on assessing vulnerability, impacts and adaptation to climate change. Consultation Document, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, 198 p

United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) (2008) Watershed approach framework. https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/watershed-approach-framework.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pulhin, J.M. et al. (2022). Participatory Climate Change Adaptation Using Watershed Approach: Processes and Lessons from the Philippines. In: Ito, T., Tamura, M., Kotera, A., Ishikawa-Ishiwata, Y. (eds) Interlocal Adaptations to Climate Change in East and Southeast Asia. SpringerBriefs in Climate Studies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81207-2_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81207-2_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-81206-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-81207-2

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)