Abstract

Biodiversity does not adhere to political boundaries. Globally, more than 50% of all terrestrial species have a range that crosses an international border. This includes more than 50% of all mammals, 25% of all amphibians and almost 70% of all birds. Of the threatened species, over 20% had a transboundary range (Mason et al., 2020). Covering a total area of more than 1.5 million km2 in six Central African countries (Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo and Democratic Republic of Congo), the so-called Congo Basin forests are the second largest tropical forest in the world after the Amazon Basin. They form the most diverse assemblage of plants and animals in Africa, and are home to some 10,000 species of plants, 1,000 birds, 700 fish and 400 mammals, including many iconic species such as forest elephants, lowland gorillas and chimpanzees. Currently, almost 15% of the total forest area of the Congo Basin has protected area status. The management of these protected areas is now based on a new paradigm: the landscape conservation approach. Twelve landscapes have been identified as priorities in the Congo Basin because of their relative taxonomic importance, overall integrity, and the resilience of the ecological processes they represent. Among these landscapes, the TRIDOM (Trinational Dja-Odzala-Minkébé) (Cameroon, Congo and Gabon) and TNS (Trinational Sangha) (Cameroon, Congo and Central African Republic) stand out as hosting the majority of the last remaining forest elephants, lowland gorillas and chimpanzees in Central Africa. The presence of four of the eight natural World Heritage sites in the Congo Basin forests testifies to the exceptional importance of these two contiguous transboundary landscapes. This article will review the evolution of regional cooperation for the conservation of biodiversity in the Congo Basin forests by providing feedback on actions carried out in the TRIDOM and TNS landscapes.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Biodiversity does not adhere to political boundaries. Globally, more than 50% of all terrestrial species have a range that crosses an international border. This includes more than 50% of all mammals, 25% of all amphibians and almost 70% of all birds. Of the threatened species, over 20% had a transboundary range (Mason et al., 2020). Covering a total area of more than 1.5 million km2 in six Central African countries (Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Central African Republic, Republic of Congo and Democratic Republic of Congo), the so-called Congo Basin forests are the second largest tropical forest in the world after the Amazon Basin. They form the most diverse assemblage of plants and animals in Africa, and are home to some 10,000 species of plants, 1,000 birds, 700 fish and 400 mammals, including many iconic species such as forest elephants, lowland gorillas and chimpanzees. Currently, almost 15% of the total forest area of the Congo Basin has protected area status. The management of these protected areas is now based on a new paradigm: the landscape conservation approach. Twelve landscapes have been identified as priorities in the Congo Basin because of their relative taxonomic importance, overall integrity, and the resilience of the ecological processes they represent. Among these landscapes, the TRIDOM (Trinational Dja-Odzala-Minkébé) (Cameroon, Congo and Gabon) and TNS (Trinational Sangha) (Cameroon, Congo and Central African Republic) stand out as hosting the majority of the last remaining forest elephants, lowland gorillas and chimpanzees in Central Africa. The presence of fourFootnote 1 of the eightFootnote 2 natural World Heritage sites in the Congo Basin forests testifies to the exceptional importance of these two contiguous transboundary landscapes. This article will review the evolution of regional cooperation for the conservation of biodiversity in the Congo Basin forests by providing feedback on actions carried out in the TRIDOM and TNS landscapes.

Regional cooperation for the conservation of biodiversity in the Congo Basin Forests

The first biodiversity conservation actions in Central Africa began during the colonial period, at the beginning of the twentieth century. These actions were based on the strategy of resting sites in the face of potentially abusive exploitation of large fauna or timber. The first national parks were created in the 1920s and the number increased after the Second World War. It was mainly in the 1960s and 1970s that some countries strengthened their network of protected areas. From the second half of the 1980s and following the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, initiatives were set up to respond to the challenges of the degradation of protected areas in Central Africa and the difficulties of justifying conservation actions to countries wishing to pursue a development strategy centred on the exploitation of natural resources. It was in this context that the ‘Conservation and Rational Use of Central African Forest Ecosystems’ (ECOFAC) Programme and the Central African Regional Programme for the Environment (CARPE) were initiated in 1992 and 1995 respectively by the European Union and USAID. The regional cooperation process was strengthened by the Conference on Dense and Humid Forest Ecosystems of Central Africa (CEFDHAC) in 1996, and then by the first summit of Central African Heads of State on the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Tropical Forests in Yaoundé (Yaoundé Declaration) in 1999.

Since the 2000s, regional dynamics have been strengthened, particularly from an institutional and functional point of view. In response to the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 54/214 of February 2000, which called on the international community to support the implementation of the Yaoundé Declaration, regional cooperation was consolidated with the establishment of the Central African Forest Commission (COMIFAC) and the Congo Basin Forest Partnership (CBFP). COMIFAC has thus become the regional institution responsible for guiding and harmonizing forestry and environmental policies for the conservation and sustainable management of the region’s forest ecosystems.Footnote 3 Launched at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002, the CBFP aims to coordinate the initiatives of the various partners in order to improve the coherence and effectiveness of their programmes and policies for the sustainable development of forest ecosystems.Footnote 4

The strengthening of the institutional and functional framework put in place enabled many donors to intensify their financial support and international conservation NGOs, such as the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF), African Parks (AP), the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) to establish themselves in the region through various programmes and projects at national and regional level. It was in this context that the UNESCO World Heritage Centre and its partners launched the Central Africa World Heritage Forest Initiative (CAWHFI) to promote a transboundary network of protected areas and new World Heritage sites in the region.

The rise of the landscape approach for conservation in the Congo Basin

The forests of Central Africa are an exceptional natural heritage and home to a significant part of the world’s biodiversity. However, while species diversity is high in these forests, their abundance is decreasing (de Wasseige et al., 2015). The current conservation system, based on limited coverage of the forest area by protected areas and variable protection capacities, is not effective in ensuring long-term protection of all species and ecosystems. This has led to a shift in conservation strategies in recent years with the emphasis on the landscape approach to conservation.

This landscape approach aims to plan and undertake integrated conservation and land management actions at a scale that encompasses entire ecosystems and takes into account the interests of stakeholders such as local communities and the private sector (logging, mining and agro-industrial concessions on the periphery of protected areas). This facilitates more effective conservation, rational and sustainable use of natural resources, and greater social and economic involvement of communities. For conservation, the landscape approach helps to ensure the integrity and connectivity of protected areas and their peripheral zones. The strategy is to manage the impact of human activities on ecosystems in such a way as to maintain genetic flows and biological processes, thus preventing habitat fragmentation and protected areas from becoming isolated pockets of biodiversity.

The landscape concept is a central axis of the COMIFAC strategic plan. Twelve landscapes covering an area of almost 700,000 km2 are prioritized by COMIFAC (Figure 1) because of their relative taxonomic importance, overall integrity and resilience to ecological processes:Footnote 5

-

Monte Alen-Mont de Cristal (Gabon, Equatorial Guinea),

-

Gamba-Mayumba-Conkouati (Congo, Gabon),

-

Lope-Chaillu-Louesse (Congo, Gabon),

-

Dja-Odzala-Minkebe (TRIDOM) (Cameroon, Congo, Gabon),

-

Trinational de la Sangha (TNS) (Cameroon, Congo and Central African Republic),

-

Leconi-Bateke-Lefini (Congo, Gabon),

-

Lac Tele-Lac Tumba (Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo),

-

Salonga-Lukenie-Sankuru (Democratic Republic of Congo),

-

Maringa-Lopori-Wamba (Democratic Republic of Congo),

-

Maiko-Tayna-Kahuzi-Biega (Democratic Republic of Congo),

-

Ituri-Epulu-Aru (Democratic Republic of Congo),

-

Virunga (Democratic Republic of Congo).

Since some of the ecological landscapes straddle international borders, transboundary collaboration is an important element in promoting coordinated actions. Among the 12 COMIFAC priority landscapes, TNS and TRIDOM are recognized by international agreements signed in 2000Footnote 6 and 2005,Footnote 7 which encourage cooperation between the countries concerned for environmental monitoring and law enforcement.

The Greater TRIDOM-TNS: A cross-border landscape under increasing pressure

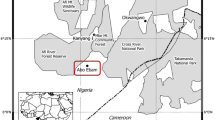

The Greater TRIDOM-TNS landscape covers a vast expanse of over 250,000 km2 of almost continuous tropical rainforest that straddles the borders of four countries (Cameroon, Congo, Gabon, and Central African Republic). Covering about 15% of Central Africa’s forests, this nearly intact transboundary forest landscape comprises two sub-landscapes: the TRIDOM, which covers more than 178,000 km2 in Cameroon, Congo and Gabon, and the TNS, which covers more than 40,000 km2 in Cameroon, Congo and the Central African Republic. Given that the habitat linking them is virtually contiguous and the socio-economic context is similar (i.e. logging and mining concessions on the periphery of the protected areas), the so-called Greater TRIDOM-TNS also encompasses the Lopé National Park in Gabon, a mixed World Heritage site (both natural and cultural), as well as the Lac Tele Community Reserve in Congo (an important area of swamp forest recognized as a Ramsar site).

The Greater TRIDOM-TNS offers a good representation of the fauna and flora of the Congo Basin, and is notable for hosting the majority of the last remaining forest elephants, lowland gorillas and chimpanzees in Central Africa. The Greater TRIDOM-TNS covers 17 protected areas including 6 in Cameroon, 5 in Congo, 4 in Gabon and 2 in the Central African Republic (Figure 2). It has four sites on the World Heritage List, three sites on World Heritage Tentative Lists,Footnote 8 two UNESCO-recognized biosphere reserves and seven Ramsar sites (Table 1), and testifies the importance and exceptional biodiversity of this landscape. Some of these protected areas may even have multiple international designations.

Although about a quarter of the Greater TRIDOM-TNS area has protected area status, pressures and threats on the periphery and in the inter-zones linking them are increasing. Indeed, almost all the forest between the protected areas is under the control of extractive industries (forestry, mining and agro-industry) (Figures 3 and 4). Other threats, such as infrastructure development (roads, dams, etc.), poaching and unsustainable natural resource extraction have intensified in recent decades, leading to higher rates of deforestation and increased habitat fragmentation (Figure 5). Transboundary cooperation is therefore a crucial element in addressing these growing pressures in a coordinated and concerted manner.

Towards a transboundary network of protected areas and new World Heritage sites in the Greater TRIDOM-TNS

The Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (World Heritage Convention) adopted by the UNESCO General Conference in 1972 has as its main mission the identification and protection of sites of ‘Outstanding Universal Value’ (OUV) to humanity. The World Heritage Convention has become one of the most robust international instruments for recognizing the world’s most outstanding natural places, characterized by their biodiversity, ecosystems, geology or remarkable natural phenomena.

Launched in 2002 by UNESCO’s World Heritage Centre, the Central Africa World Heritage Forest Initiative (CAWHFI) aims to promote the importance of the natural heritage of the Congo Basin, to improve the geographical representation of World Heritage sites in this region, and to support the establishment of a transboundary network of protected areas based on the World Heritage Convention (UNESCO, 2010).

At the time of the launch of CAWHFI, with the exception of the Dja Faunal Reserve in Cameroon, all World Heritage sites in the Congo Basin forests were in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Building on the strengthening of the institutional and functional framework in the Greater TRIDOM-TNS in the early 2000s, CAWHFI was able to provide technical support to the authorities of the countries concerned in the preparation of new nomination dossiers. This effort led to the inscription of three outstanding sites on the World Heritage List:

-

the Ecosystem and Relict Cultural Landscape of Lopé-Okanda in Gabon in 2007: the first mixed site (nature/culture) in Central Africa;

-

the Sangha Tri-National (TNS) in Cameroon, Congo, Central African Republic in 2012: the first natural tripartite transboundary site; and

-

the Ivindo National Park in Gabon.

CAWHFI also supported the preparation of nomination dossiers for the Odzala-Kokoua (Congo) national park that was officially submitted in 2021. This dossier is currently undergoing technical evaluation by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), an independent advisory body designated by the World Heritage Convention. If this site is inscribed, the Greater TRIDOM-TNS will have five World Heritage sites, covering about 15% of its area and 50% of the protected areas in the landscape.

The inscription of a site on the World Heritage List is not an end in itself. The state of conservation of properties is regularly reviewed by the various monitoring mechanisms of the World Heritage Convention. To this end, site managers and local authorities work continuously with the technical support of the World Heritage Centre to ensure the management, monitoring and preservation of these properties. Between 2016 and 2020, European Union funding of €5 million has enabled CAWHFI to strengthen the management of a transboundary network of protected areas and World Heritage sites in the Greater TRIDOM-TNS through the multiplication of anti-poaching patrol efforts (more than 3,500 patrols and 300,000 km covered), the use of innovative technologies (SMART, trap cameras, drones and remote sensing, etc.) and the training of more than 350 eco-guards. CAWHFI’s support has also improved site management through the rehabilitation of infrastructure, the promotion of eco-tourism, the involvement and training of local communities (over 1,000 people) and the updating/production of wildlife inventories (e.g. elephants, gorillas and chimpanzees). All these field actions have facilitated the exchange of experiences between managers of different protected areas (Figure 6) as well as decision-making at the landscape level. For example, CAWHFI supported the process that led to an agreement in principle for the integration of an ecological corridor into the TRIDOM land-use planning and sustainable development schemes in Cameroon.

Perspectives for strengthening cross-border cooperation in the Greater TRIDOM-TNS

The strengthening of the institutional and functional framework put in place in Central Africa in the early 2000s has allowed many donors to increase their financial support and international conservation NGOs to establish themselves in the region on a sustainable basis through various programmes and projects at national and regional levels. The landscape approach to conserving the biodiversity of the Congo Basin forests has fostered regional cooperation and enabled the integration of other stakeholders, such as local communities and the private sector, into decision-making processes. The emergence of a transboundary network of protected areas and new World Heritage sites in the Greater TRIDOM-TNS based on the World Heritage Convention can therefore be used as a lever to strengthen forest governance in the landscape. Despite these significant advances, forest governance in the Congo Basin countries is still weak. Coordination between institutions on land and forest governance issues is insufficient and there is a crucial need to harmonize sectoral policies at national level to strengthen transboundary cooperation. Thus, the consolidation of partnerships with the private sector, the certification process in favour of sustainable forest management (FSC), and the promotion of integrated and sustainable planning tools (environmental and social impact studies, land use planning, etc.) remain encouraging vectors for good forest management at national level.

Notes

- 1.

Dja Faunal Reserve (Cameroon), Sangha Trinational (Cameroon, Congo, Central African Republic), Ecosystem and Relict Cultural Landscape of Lopé-Okanda (Gabon), Ivindo National Park (Gabon).

- 2.

Dja Faunal Reserve (Cameroon), Sangha Trinational (Cameroon, Congo, Central African Republic), Ecosystem and Relict Cultural Landscape of Lopé-Okanda (Gabon), Ivindo National Park (Gabon), Virunga National Park, Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Salong National Park, Okapi Wildlife Reserve (Democratic Republic of Congo).

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

Inventory of properties which each State Party intends to nominate for inscription on the World Heritage List.

References

de Wasseige, C., Tadoum, M., Eba’a Atyi, R. and Doumenge, C. (eds). 2015. Les forêts du Bassin du Congo – Forêts et changements climatiques. Retrieved from: https://www.observatoire-comifac.net/publications/edf/2015

Mason, N., Ward, M., Watson, J. E. M., Venter, O. and Runting, R. K. 2020. Global opportunities and challenges for transboundary conservation. Nature Ecology and Evolution, Vol. 4, pp. 694–701.

UNESCO. 2010. Patrimoine mondial dans le bassin du Congo. Paris, UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-628-2.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the UNESCO, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the UNESCO, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

Any dispute related to the use of the works of the UNESCO that cannot be settled amicably shall be submitted to arbitration pursuant to the UNCITRAL rules. The use of the UNESCO's name for any purpose other than for attribution, and the use of the UNESCO's logo, shall be subject to a separate written license agreement between the UNESCO and the user and is not authorized as part of this CC-IGO license. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the license.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 UNESCO

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Resende, T.C., Meikengang, A.G. (2023). Regional cooperation for the conservation of biodiversity in the Congo Basin forests: Feedback on actions carried out in the TRIDOM-TNS landscapes. In: Houehounha, D., Moukala, E. (eds) Managing Transnational UNESCO World Heritage sites in Africa. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80910-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80910-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-80909-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-80910-2

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)