Abstract

What are the patterns in media coverage in Swiss energy policy-making, and to what extent do the media influence voters’ decisions at the ballot? In a first step, this chapter provides a comparative investigation of media coverage in the run-up to three recent energy-related referenda (2015 initiative “Energy tax instead of VAT”; 2016 nuclear phase-out initiative; 2017 referendum on the federal Energy Strategy 2050), with 31 other referenda between 2014 and 2018 as a benchmark. Based on a content analysis of articles published in 21 Swiss newspapers, our analysis demonstrates that the three energy-policy referenda are characterized by patterns similar to non-energy votes but also have distinct features. In a second step, we specifically focus on the 2016 nuclear phase-out initiative, which was characterized by balanced newspaper reporting, and explain voting behavior by linking data on media coverage and individual-level data from a panel survey (n = 1014). The analysis relies on “linkage analysis”, a method that takes media contents as quasi-experimental stimuli to explain individual-level outcomes. We find that the failure of the phase-out initiative can be partly explained by exposure to newspaper coverage: one in four left-wing voters who had initially been in favor of the popular initiative but were exposed to strongly negative coverage about it during the “hot” campaign phase changed their initial voting intention. The analysis also suggests that the media coverage may have helped center/right-wing voters to learn about their preferred party’s position so as to align their vote choice with their political predisposition.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Direct democracy is an important component of Switzerland’s political DNA. On average, Swiss citizens were called to vote on eight federal ballot propositions per year since the beginning of the century. In international comparison, there is no country in which direct democratic votes are held as frequently as in Switzerland. While energy topics had been absent from the voting agenda for more than a decade, a number of direct democratic votes with important implications for the country’s energy system have been held at the federal level since 2015. In this chapter, we discuss two interrelated questions with respect to these direct democratic votes: First, what are the patterns of media coverage of energy topics in the run-up to direct democratic votes? And second, to what extent does media reporting influence citizens’ vote decision?

Media coverage about referendum campaignsFootnote 1 has received increasing scholarly attention not only in Switzerland but also internationally. So far, most analyses fall into two camps, focusing either on the media as a “mirror” of society or as a “molder” of society. On the one hand, scholars analyze media coverage as a dependent variable, asking which factors actually shape the news. On the other hand, scholars use media coverage as an independent variable to examine possible effects on decision-making. In this vein, linkage studies often examine whether frames and arguments salient in media coverage can be linked to citizens’ decision-making. Scholars also use the overall intensity and tonality of media coverage in order to explain voting behavior. Encompassing analyses, however, which examine the dual role of the media both as a dependent and independent variable are rare, with the study led by Hanspeter Kriesi being the most notable exception.Footnote 2 In this chapter, we try to address this shortcoming by showing how media coverage about three energy-related proposals can be explained and by illuminating how media coverage about one energy policy-related proposal, the nuclear phase-out initiative, affected voting behavior.

The chapter is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we first provide some context by reviewing research on media coverage in referendum campaigns. Next, we empirically investigate how three recent energy-related direct democratic votes were covered by the media, also in comparison with other direct democratic votes. Sect. 3 starts by deriving several theoretical expectations regarding the influence of media coverage on voting behavior, before using the case of the nuclear phase-out initiative (2016) to investigate these expectations empirically. The chapter concludes by discussing implications for Swiss energy governance and further research.

2 Media Coverage in Referendum Campaigns

2.1 Research on Media Coverage About Swiss Referenda

An important strand of research on the role of media in direct democracy focuses on media coverage as a dependent variable, evaluating the quality of media coverageFootnote 3 and asking which factors shape news reporting. When it comes to explaining actual media coverage, most data comes from the Swiss case. This is not surprising because the Swiss case offers excellent conditions for comparative analyses. This stream of research argues that media coverage largely reflects power structures in society and actual campaign activities, which is why media do not cover all votes, actors or arguments with the same intensity and tonality. Hence, media often quote political actors who hold important positions and have official roles in the campaigns (e.g., referendum committees), and they often report on actors’ campaign activities such as press conferences.Footnote 4 In a comparative analysis, Linards Udris and colleagues found that the amount of media attention to a referendum in the “hot” phase of the campaign cannot be explained with the “real” degree of contestation (e.g., inner-party conflicts), the status of the challengers or the temporal proximity of the vote in parliament or at the polls (both opinion polls and final results).Footnote 5 Instead, media attention is higher if at least one of the following conditions is present: a) media attention was already high in an earlier phase, b) the referendum is about “identity politics” or the cultural dimension of political conflicts (e.g., the initiative against “mass immigration”) rather than socio-economic issues, c) the challengers use populist rhetoric, or d) political advertising expenditures are high, which evidently favors political actors from the right, since they normally have a relatively large campaign budget.Footnote 6 Matthias Gerth and colleagues also argue that issue characteristics matter: familiar and uncomplex issues (e.g., asylum policy) trigger more attention than unfamiliar, complex issues (e.g., tax reform).Footnote 7

At the same time, media do not merely follow political agendas but also shape news coverage according to their own logics. This is illustrated by the considerable differences in media attention among media types, for instance between tabloid and quality media, with the former investing fewer resources and producing fewer articles than the latter. These differences can be explained with different structural features of these media types and thus different organizational routines and logics.Footnote 8 Furthermore, ownership structures shape news coverage; media with close ties to political parties or milieus tend to take a political stance in their reporting, including on referenda.Footnote 9 Finally, with the ongoing commercialization of the media, media tend to frame politics, including referendum campaigns, as a “horse race” between political actors, stressing contestation and tactics instead of issue substance.Footnote 10 These findings point to certain deficits in the quality of media coverage. In sum, however, the empirical literature paints a rather positive picture of Swiss media coverage. Initiatives and referenda are considered “routine and ritualized business” for Swiss media and most votes are covered in a more or less substantial and objective way.Footnote 11

Within the growing literature on referendum coverage in Swiss media, energy-related referenda, however, have not played a role recently. Scholars are either concerned with general patterns across policy issuesFootnote 12 or have empirically investigated other policy fields such as social policyFootnote 13 or migration, traffic, and foreign policy.Footnote 14 The few available recent studies on Swiss energy policy do not focus on referendum debates in news media but on TwitterFootnote 15 or focus on media coverage not about a specific referendum campaign but on the aftermath of the Fukushima accident in general.Footnote 16

This dearth of research is unfortunate because in recent years, the number of energy-related votes at the national level has increased. Since 2015, Swiss citizens have voted on three different energy-related proposals (see Table 1): the popular initiative “Energy tax instead of VAT” by the Green Liberal Party (GLP) in March 2015 (henceforth “GLP initiative”), the popular initiative on a nuclear phase-out (“Atomausstiegsinitiative”) by the Green Party (GP) in November 2016 and the referendum on the national Energy Strategy 2050 in May 2017 (henceforth “ES2050”).Footnote 17 After a break of more than a decade—energy-related referenda peaked between 2000 and 2003—these recent votes have brought energy policy back on the voting agenda. While two popular initiatives attempted to challenge the status quo by advocating for more renewable energies, the referendum against the federal Energy Strategy 2050 tried to keep the status quo by blocking an encompassing move away from nuclear energy and fossil fuels toward renewable energies. Is the growing importance of energy policy and the according conflict also reflected in media coverage? Knowing that public votes are, by and large, “routine business” for Swiss media, we expect the media, of course, to devote their attention also to these energy-related proposals. But how much and in which way is an open question which we investigate in Sect. 2.2.

2.2 Media Coverage of Recent Energy-Related Referenda

In order to determine and contextualize media attention to public votes and tonality towards these votes, we rely on data from the “Abstimmungsmonitor”, a project at fög—Forschungszentrum Öffentlichkeit und Gesellschaft (University of Zurich), which has examined news coverage about national public votes in Switzerland since 2013. Data from the “Abstimmungsmonitor” (monitor on public votes, henceforth “monitor”) has been used for case studiesFootnote 18 and comparative analyses.Footnote 19 Short reports on each voting day are publicly available on the website of the research center.Footnote 20

In order to rely on the same media sample and time frame for each public vote, the monitor data is based on a standardized data collection approach. The entire sample now consists of news coverage about 34 different public votes between 2014 and 2018 published in 21 different news outlets during 11 weeks in the run-up to the vote (starting 12 weeks before voting day until 1 week before voting day). The sample yields 9951 news articles in total, 1046 of which relate to the three energy-related referenda. The newspaper sample covers a broad spectrum in terms of regional diversity, including 15 outlets from German-speaking Switzerland and 6 from French-speaking Switzerland, and in terms of media types, ranging from low-quality tabloid and commuter papers to more mid-market regional papers (e.g., Südostschweiz) to high-quality papers (e.g., Neue Zürcher Zeitung), and including daily papers, Sunday papers and one weekly magazine.Footnote 21

Apart from the number of articles (a proxy for media attention), the monitor data includes information on tonality, which is measured at the article level. Each article is assigned a type of tonality, with “positive” indicating an article primarily conveying a message of support for the proposal, for instance an editorial or a report describing the press conference of the proponents; “negative” conveying rejection; and “ambivalent” including rather balanced (or ambivalent) messages. Next, an aggregated tonality score is constructed at the newspaper level by subtracting the number of negative articles from the number of positive ones, dividing the result by the overall number of articles (including articles with ambivalent tonality) and multiplying by 100. Hence, the aggregated tonality score is bounded between −100 and 100. In addition, for each article, the data includes up to three actors (individual or collective actors) with a statement on the proposal, including the stance an actor takes (positive, negative, ambivalent). In the data analysis, for each collective actor (e.g., SVP) or actor type (e.g., experts), a score that displays the overall acceptance towards the proposal is shown. This actor-level score is calculated in the same way as the article-level tonality score discussed above.

We now present the results from our comparative analysis of media coverage. First, we focus on media attention and tonality; second, we shed light on differences among media outlets; and third, we highlight actor constellations in the three energy-related referenda.

Table 2 shows the amount of media attention and the tonality towards the three recent energy-related proposals in comparison with 31 other votes. We display initiatives (Volksinitiativen) and referenda in the narrow sense (Referenden against federal proposals) separately, since they have different institutional characteristics (initiatives are initiated bottom-up, federal proposals top-down) and different tonality directions—support for challengers takes a positive tonality in the case of initiatives but a negative tonality in the case of federal proposals. The three referenda share common features, but they differ in terms of attention and tonality. The data shows relatively low media attention to the GLP initiative in 2015, while both the nuclear phase-out initiative in 2016 and the energy referendum ES2050 in 2017 triggered much more media coverage than other votes.

We argue that the following factors help explain these differences in media attention.Footnote 22 Political advertising expenditures, which usually correlate with overall media attention, were below average in the run-up to the GLP initiative and above average in the other two cases, with the number of political ads as a possible proxy.Footnote 23 Furthermore, only the two referenda with high media attention included debates on nuclear energy, while the GLP initiative focused more on renewable energy and on financial policy in general. This difference in issue characteristics is important, since nuclear energy has been found to be extensively and intensively covered by the media, especially after the accident at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.Footnote 24 In this sense, in gauging the newsworthiness of an issue in the “hot” phase, journalists use previous media attention as a yardstick.Footnote 25 We can also argue that the GLP initiative constituted a more technical and unfamiliar issue; hence it was less attractive and more difficult for the media to cover. The nuclear phase-out initiative and ES2050, on the other hand, with their focus on nuclear energy (in the case of the phase-out initiative including a date to end electricity generation based on nuclear energy) represented a more familiar and concrete issue.

As regards tonality, media coverage is, on average, negative towards initiatives and positive towards federal proposals (see Table 2). Given that federal proposals have, on average, good chances to withstand a referendum, while the majority of popular initiatives is rejected, this supports the finding that media typically reflect the majority view of political actors and the final voting result. However, the three energy proposals fit this pattern to different extents. Media coverage about the GLP initiative was indeed typical of media coverage about initiatives, even though criticism in this case was even more pronounced. (In this light, the very low approval rate at the polls is not surprising.) In comparison, the nuclear phase-out initiative found more support and less criticism in media coverage than expected. Unlike other initiatives, tonality towards the nuclear phase-out was ambivalent, i.e., the numbers of articles supportive and critical of the initiative were about equal. The Green Party as a challenger of the status quo thus managed to stimulate a salient and multifaceted debate, with their proposal finding more support in the media than average initiatives. Finally, on average, the media portrayed the ES2050 only in a slightly positive light compared to other federal proposals. Hence, the federal energy strategy was a hotly debated and controversial issue in the media, a finding that is mirrored by the diversity of views about the implementation of the ES2050 among stakeholders of the Swiss energy system, as documented by a stakeholder survey conducted within the work package “Energy Governance” of SCCER-CREST.Footnote 26

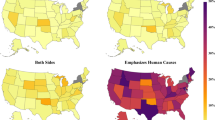

At the same time, media coverage differed considerably among newspapers (see Fig. 1). This is not surprising, since each newspaper is embedded in a different context, reflecting both the specific political climate in cantons and regions and, above all, specific ownership and production structures. For the data analysis, we combined the three energy-related proposals, as positive tonality in all cases ultimately means support for more “green” policies and renewable energies. Through this comparison, large differences among newspapers become clear. Weltwoche (−64), Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ; −31) and its sister paper NZZ am Sonntag (−35) and Basler Zeitung (−32) had the most negative tonality scores, while Le Matin (+32) and its sister paper Le Matin Dimanche (+19) and Blick (+25) displayed the most positive tonality scores. The positive tonality apparent in newspapers from Suisse romande (e.g., Le Matin, Le Matin Dimanche, Tribune de Genève) seems to reflect a political climate more favorable to renewable energies, as is also attested in the final voting results. As concerns negative tonality, ownership structures might indeed be another explanatory factor. Weltwoche and Basler Zeitung (at that time) were owned by political actors from the SVP, and NZZ is owned by shareholders who are obliged to be either members of the FDP or have a “liberal” (“freisinnig-demokratisch” in German, in the sense of conservative liberalism) worldview. Both SVP and FDP were more or less critical of renewable energy policies and of phasing out nuclear energy. In media coverage, journalists then seemed to align with the official or long-standing political stance of their newspapers, which is in line with earlier findings.Footnote 27

Apart from media-specific factors, the overall support or rejection reflected in the tonality is a specific result of actor constellations and political conflict. This is illustrated by the media attention that was given to different actors (Table 3) and actors’ acceptance of proposals (based on their statements; Table 4). With respect to the latter, +100 means that all statements of an actor are positive (indicating support), −100 means that all statements of an actor are negative (indicating rejection), and 0 means that either the actor uses ambivalent messages or there are various competing factions within a collective actor (e.g., within a political party). Table 3 (media attention) and Table 4 (acceptance) show that each referendum followed a specific pattern. The overall negative tonality towards the GLP initiative was also reflected in the actor constellation. Apart from the GLP, this initiative received some support only from the Green Party (6%; +75), while almost all other actor groups were quoted with primarily negative messages.

In contrast, the nuclear phase-out initiative and ES2050 proposal were much more contested, albeit with different conflict constellations. The nuclear phase-out received support not only from the Green Party but also from the GLP, the Social Democrats and parts of civil society and experts. Notably, when media used comments and their own evaluations, there was a balance between support and rejection—unlike in the case of the GLP initiative. In terms of media attention, the Green Party was highly visible (14%; +99), as were its opponents representing incumbent business interests such as those from the nuclear sector (“economy”, 15%; −79) and the center-right parties including SVP, FDP and CVP (collective media attention: 16%). In sum, this media portrayal followed a rather “classic” energy- and environment-related conflict in the economic left-right dimension, with some support by the media themselves.Footnote 28

Media coverage about ES2050 shows that the majority of actors used favorable messages, but two large parties, which were also the parties with the highest media attention, were either highly critical (SVP: 13%; −85) or internally divided (FDP: 10%; −20). Support from economic actors, which gained much media coverage, remained limited (12%; only +16), again pointing at competing positions and conflict among economic organizations. In addition, parts of civil society were somewhat skeptical towards ES2050 (−9), as were the media themselves (−10), especially right-wing leaning media from German-speaking Switzerland (cf. above). In sum, media portrayal of ES2050 did not follow a “classic” economic left-right conflict but rather showed internal conflict among the center-right and the economy.

Finally, when it comes to actual dynamics in media coverage about referenda in general, the overall campaign period is usually relatively short. The “hot” phase typically begins around 6 to 4 weeks before voting day and intensifies until a climax is reached around three to 1 week(s) before voting day. Dynamics in media reporting are usually linked to dynamics in campaign activities and to the timing of voters’ decision-making. For instance, many citizens send out their ballots by mail during the “hot” campaign phase.Footnote 29 During this peak period, media publish more than three to four times as many articles per week compared to two or more months before the vote. At the same time, media coverage typically does not intensify any longer, the closer the voting day gets.

Broadly speaking, votes on energy policy are no exception to this rule. However, some interesting deviations can be observed (see Fig. 2). First, both ES2050 and the nuclear phase-out initiative showed an unusually marked increase in media attention even in the second week before voting day, while media coverage on the GLP initiative began to stagnate earlier on. Second, media attention to ES2050 started rather early, also because parliamentary debates on related issues (in particular hydropower) that were taking place at the same time were discursively linked to the ongoing referendum campaign. In this sense, the “hot” phase of the ES2050 lasted longer than on average, while the nuclear phase-out initiative showed the most intense, i.e., most “condensed” media coverage.

To conclude, media coverage about all three proposals reflected the actor constellations and foreshadowed the final voting result. Hence, the two initiatives were portrayed less favorably than the federal proposal. However, the GLP initiative found much less media attention and was rejected even more strongly than is typically the case for popular initiatives (both at the ballot and as measured through the tonality index), while the nuclear phase-out initiative, in contrast to other initiatives, was characterized by a balanced amount of supportive and critical newspaper articles. As the high level of media attention indicates, both the nuclear phase-out initiative and the ES2050 were heavily contested, and the latter triggered more criticism than the average federal proposal. The strong contestation was at the time also underlined by survey results indicating a close race between proponents and opponents a few weeks before the vote. But the nature of contestation differed between the cases. The ES2050 media coverage pointed at internal conflicts within the FDP and among economic actors, i.e., disagreements within political and economic elites. Media coverage about the nuclear phase-out initiative, on the other hand, reflected well-known conflict constellations with two antagonistic camps, i.e., between left-wing actors in favor of an expedited nuclear phase-out and economic and right-wing actors (plus the Federal Council) campaigning unitedly against such a measure.

3 The Role of Media Coverage in Explaining the Result of the Nuclear Phase-Out Vote

While Sect. 2 has provided insights into media coverage of energy-related referenda as a dependent variable, we now focus on media coverage as an independent variable. Based on a linkage approach, we test to what extent the tonality of media coverage affects citizens’ decision-making and voting behavior. We do this by studying the case of the 2016 nuclear phase-out initiative. We selected this case because it allows, we believe, even better testing of several effects known from the literature on electoral choice. As shown above, media attention to the nuclear phase-out initiative was relatively high; thus, citizens were potentially confronted with a lot of information. This was also true for the ES2050, but not for the GLP initiative. Information on the nuclear phase-out initiative conveyed an almost “perfectly” ambivalent tonality in terms of support and rejection, while the ES2050 was characterized by a slightly positive aggregated tonality and the GLP initiative by a clearly negative one. Therefore, at the individual level, we assume to detect a lot of variation with respect to exposure to different kinds of tonality regarding the phase-out proposal. Moreover, unlike the media debate on the ES2050, the debate surrounding the nuclear phase-out initiative conveyed clear actor and conflict constellations well-known from partisan politics. In sum, citizens potentially received much information—“new” information regarding the (surprisingly) ambivalent tonality but also “old” information regarding the well-known actor constellation. We examine this configuration in light of the literature on campaign effects.

3.1 Campaign Effects

As noted by McCombs and Shaw almost half a century ago, “the pledges, promises, and rhetoric encapsulated in news stories, columns, and editorials constitute much of the information upon which a voting decision has to be made.”Footnote 30 Despite the changes in the relevance of communication channels and media systems that have occurred since then, the news media still play a major role as a transmission belt in today’s democracies in general and in helping citizens to form vote choices in particular.Footnote 31 For Switzerland’s direct democratic system, it has been shown that voters rely strongly on the media (especially newspapers) as a source of information to form their voting preferences.Footnote 32

What kinds of effects can be expected to be brought about by media coverage in the run-up to a direct democratic vote? Research on campaign effects often draws on the classical work of Lazarsfeld and colleagues.Footnote 33 Accordingly, an electoral campaign may have three distinct effects. First, it can lead to a reinforcement of voters’ initial intentions; that is, voters have already formed certain intentions at the outset of a campaign and these become reinforced over the course of the latter. Second, voters may have no voting intentions at the beginning of a campaign, but the latter activates their latent political predispositions and thereby helps them to take a vote choice—a mechanism called activation or crystallization. As a third possibility, a campaign may induce voters to rethink their original voting intention, leading to a conversion in the sense that they take a choice that is different from their original voting intention. As Kriesi and SciariniFootnote 34 pointed out, a campaign may bring about a fourth effect: voters who have a specific voting intention at the outset of a campaign may finally refrain from casting a vote. This fourth campaign effect may be called demobilization.

When it comes to media effects, our baseline expectation is that exposure to positive coverage—i.e., news coverage favorable about the ballot proposition—increases the probability of voting in favor of it vis-à-vis casting a “no”-vote (hypothesis 1).

Positive coverage should reinforce the voting intentions of voters who already had favorable intentions before, especially by reinforcing known arguments in favor of the proposal and potentially providing new ones. For voters with initially negative voting intentions, one may expect positive coverage to lead to a persuasion effect. However, this view ignores voters’ political predispositions including their partisan orientation, which can be expected to condition the effects of exposure to media coverage. Referendum campaigns not only help voters to gain issue-specific knowledge but also to learn about the positions political parties take on a ballot proposition.Footnote 35 Many voters use information about a party’s stance on a political issue as shortcuts in forming their own preferences,Footnote 36 and the relevance of this partisan heuristic has also been demonstrated in the context of Swiss direct democratic votes.Footnote 37 In sum, in the context of the nuclear phase-out initiative, which was characterized by the long-standing ideological divide between (nuclear-skeptic) left-wing and (nuclear-friendly) right-wing parties,Footnote 38 we therefore expect exposure to positive media coverage about the phase-out proposal to reinforce positive voting intentions among left-party voters (hypothesis 2). For right-party voters with positive voting intentions, on the other hand, exposure to positive coverage may resonate with their prior intentions, but as the campaign advances, these voters are likely to become aware of the inconsistency between their political predisposition and their voting intention. This ambivalence can be expected to dampen any reinforcement effect.

As a mirror image to the second hypothesis, we expect exposure to negative coverage about the proposal to reinforce negative voting intentions among right-party voters (hypothesis 3). Again, we do not expect such an effect for left-party voters with initially negative voting intentions, due to the ambivalence that arises between growing awareness of one’s preferred party’s position and the original voting intention.

Based on our hypotheses, the subsequent analyses focus specifically on reinforcement effects. While we will also explore conversion and demobilization effects, our data are not suited to investigate activation effects, as will be further explained below.

3.2 Empirical Analysis of Media Effects in the Nuclear Phase-Out Vote

To examine media effects on voting behavior, we combine data from a panel survey with a content analysis of newspaper articles from the monitor database described above. We thus rely on “linkage analysis”, an approach pioneered by Arthur H. Miller and colleagues in the 1970s that uses media content as a quasi-experimental stimulus to explain individual-level variables.Footnote 39 The idea behind the method is to link media content data with survey data after having matched survey respondents with the media they actually consume. Linkage analysis is suited to identify effects of media content on individual-level variables in real-world settings, but it might be prone to underestimating the true size of effects.Footnote 40 The approach is the state-of-the-art method in media effects research and has been applied extensively in studies of the impact of news consumption on political behavior.Footnote 41 In Sect. 3.2.1 we describe our survey data, which captures the outcome of interest (voting behavior) as well as several focal explanatory and control variables. Sect. 3.2.2 presents the media content data, and Sect. 3.2.3 presents the results of our regression analyses. We discuss the results in Sect. 3.3.

3.2.1 The Survey: Sampling Strategy and Relevant Variables

To gather data on individuals’ voting behavior in the 2016 nuclear phase-out vote and other variables of interest, we fielded a panel survey with Swiss voters. The study participants were drawn from an online consumer panel operated by the Swiss market research agency Intervista. Participants were part of an entirely actively recruited pool, which included nearly 70,000 registered individuals in 2016.Footnote 42 We employed stratified random sampling with proportionate allocation to approximate a sample that demographically represents the Swiss voting population. The population was stratified by gender, age, education, partisan orientation and region, covering the German- and French-speaking parts of Switzerland.Footnote 43 Respondents were surveyed based on computer-assisted web interviews. The pre-vote questionnaire (t0, n = 1216) was administered right at the outset of the “hot” campaign phase (October 10–19, 2016). The post-vote survey (t1, n = 1014) started 1 h after the polling stations had closed (November 27) and ended 4 days later (December 1). The drop-out rate between the waves was 16.6%.Footnote 44

3.2.1.1 Dependent Variable

Our dependent variable captures voting behavior in the popular vote on the nuclear phase-out initiative in 2016. At t1, we asked whether respondents had participated in the vote and, if they had, whether they had voted in favor or not. The dependent variable finally consists of three categories: voting in favor, voting against, and abstention.

3.2.1.2 Explanatory and Control Variables

In order to investigate the possible effects of newspaper coverage on voting behavior, the pre-vote survey included an item for measuring respondents’ newspaper consumption. Respondents were given a list of 30 Swiss newspapers and asked to indicate which ones they consulted regularly to find out about political and economic issues. Respondents could choose as many papers as they wanted. These individual-level data were later on linked to data covering the tonality of newspaper reporting about the phase-out initiative (see Sect. 3.2.2).

In the post-vote survey, respondents were asked about the sources of information they had used to inform themselves about the phase-out initiative (see Fig. 4). Here, they could select among a number of sources, which also included the official governmental information booklet (Bundesbüchlein). To investigate the role government messaging might have played in shaping voting behavior, we use a dummy variable measuring whether voters had read the booklet or not.

Voters also receive advice from their social environment, e.g., through discussions with friends and family members.Footnote 45 To measure the intensity of respondents’ exposure to these sources of information, the post-vote survey included an item asking respondents to indicate the frequency with which they had discussed the popular initiative with other people around them. For eight categories,Footnote 46 respondents indicated whether they had discussed the initiative “never” (coded as 0), “rarely” (1), “sometimes” (2) or “often” (3). These data were aggregated to an additive index of exposure to social voting cues.

To assess partisan orientation, respondents were asked to indicate (at t0) which political party best represented their political views. Based on this information, we generated a variable capturing whether respondents leaned towards one of the parties supporting the initiative, a party without a clear stance, or one of the parties rejecting it. Information on stable sociodemographic variables including respondents’ gender, age, education, and place of residence were also collected at t0. Based on the latter, we generated two dummy variables. The first, “Danger Zone”, captures whether the place of residence is within a radius of 20 kilometers from one of the country’s nuclear reactors. This radius corresponds to the legally defined “danger zone”, in which a serious nuclear incident can pose a threat to the population, for which protective measures are required.Footnote 47 The second, “Language Region”, captures whether respondents live in the French- or German-speaking part of Switzerland. Finally, our analyses control for initial (t0) voting intentions and the strength of these. At t0, respondents were asked to indicate, on a 5-point scale, whether they intended to certainly (coded as 1) or rather (2) vote in favor of the initiative, had not formed a voting intention yet (3), or intended to rather (4) or certainly (5) vote against the initiative. We generated a dummy variable “Initial voting intention” to differentiate between voters intending to vote in favor and voters intending to vote against. We generated a second dummy variable “Strength of initial voting intention”, distinguishing between voters with “weak” intentions in favor or against the initiative at t0(corresponding to “2” and “4” on the 5-point scale) and voters with “strong intentions” (“1” and “5”).

3.2.2 Newspaper Data: Sample, Coding and Index Construction

In order to investigate the effects of newspaper coverage on voting behavior, the individual-level behavioral data on media consumption described in Sect. 3.2.1 were merged with data on newspaper coverage about the initiative. In general, for the latter, we relied on the newspaper-level tonality scores described in Sect. 2.2. However, our sample of newspapers used here deviates slightly from the monitor sample described in Sect. 2.2. First, the Sunday newspapers SonntagsBlick and Le Matin Dimanche were not included because they were not covered by the survey. Second, L’Hebdo was included in the linkage analysis, but was not used for the comparative analysis in Sect. 2.2 (including data between 2014 and 2018), since L’Hebdo ceased to exist in 2017. This leaves us with a sample of 10 subscription newspapers, 5 tabloid and free newspapers, and 5 Sunday newspapers. 6 of these newspapers appear in French and 14 in German.

Moreover, given that the implementation of the first survey wave was not finalized before October 20, 2016, our linkage analysis only used tonality data based on the 268 articles that were published between October 20 and November 20, 2016 (see Table 5). That way, we made sure to relate the mechanisms of reinforcement, conversion and demobilization to the newspaper coverage that happened precisely between the two survey waves. Our analysis thereby covers almost the entire “hot” phase of the referendum campaign (see Fig. 2).

Table 5 shows the numbers of articles with a positive, neutral/ambivalent or negative tonality with regard to the nuclear phase-out initiative used for the linkage analysis. The proportion of articles classified as positive (58, or 21.6%) was slightly higher than the proportion of articles classified as negative (52, or 19.4%) during the period of observation. The majority of articles (158, or 59%) was coded as neutral or ambivalent. Similar to the procedure described in Sect. 2.2, we computed tonality scores at the level of individual newspapers. These ranged from −33.3 (20 minutes) to +83.3 (L’Hebdo). To account for variations in the frequency with which different newspapers reported about the nuclear phase-out initiative, we multiplied the tonality scores by the number of articles about the nuclear phase-out initiative per publication day. The resulting normalized tonality score ranges from −18.5 (Luzerner Zeitung) to 18.5 (L’Hebdo). Next, for each respondent, we added the newspaper-level tonality scores for those newspapers that (s)he had indicated to use regularly to find out about political and economic issues. The distribution of the resulting (z-transformed) individual-level index of exposure to newspaper coverage about the nuclear phase-out initiative is shown in Fig. 3.

3.2.3 Data Analysis and Results

3.2.3.1 Frequencies: Relevance of Information Sources

In Switzerland, newspapers are perceived as (highly) important mass media channels. In a study on three referendum campaigns, newspapers were found to be among the three most important information sources, together with television and the governmental information booklet;Footnote 48 this pattern is confirmed by the regularly conducted VOTO (formerly VOX) analyses.Footnote 49 In our sample, 75% of respondents indicated that they used newspapers to inform themselves about the nuclear phase-out initiative, followed by the voting booklet published by the Federal Council (51%) and way ahead of further media like radio, television and internet sources (see Fig. 4). This underscores the importance of newspapers as a source of information in the run-up to the referendum.Footnote 50

3.2.3.2 From Initial Voting Intentions to Voting Behavior

Figure 5 indicates the extent to which initial voting intentions (t0) were in line with actual voting behavior (t1), differentiating between voters leaning towards the left-wing parties supportive of the popular initiative (a) and voters leaning towards the center-right parties that rejected the phase-out proposal (b). As Fig. 5 illustrates, there was considerable movement in voters’ preferences on both sides of the political spectrum. While 85% of left-wing voters in our sample had expressed an intention to vote in favor of the popular initiative right before the “hot” campaign phase, only 68% finally voted in favor, with the remainder either voting against (20%) or not casting a vote at all (12%).

Initial voting intentions and actual voting behavior of (a) voters leaning towards a left-wing party (including SP, Green and GLP) and (b) voters leaning towards a center-right or right-wing party (including CVP, FDP, BDP and SVP). Bar width is proportional to the size of the respective voter segment

A different pattern can be observed for voters of the parties that rejected the initiative. While there was almost a balance between supporters (46%) and opponents (52%) of the initiative at t0, only one in four right-wing voters finally voted “yes”. Half of the voters who defected from their initial support did not participate and the other half voted against. On aggregate, the majority of voters participating in both survey waves (60.5%) had expressed an intention to vote in favor of the initiative at t0, but only 45.7% of participating voters finally supported it at the ballot (compared with 45.8% in the electorate).Footnote 51 These patterns beg the question how the observed opinion swings on both sides may be explained and, in particular, what role media coverage of the phase-out initiative might have played in bringing about not only the erosion of the relatively strong cohesion of the political left between t0 and t1 but also the consolidation of the “no-camp” within the political right.

3.2.3.3 Regression Analysis

To analyze voting behavior, we start with a multinomial logistic regression analysis. This classification method is a generalization of logistic regression that can be applied if the dependent variable is categorically distributed. The dependent variable of our multinomial logit model consists of three categories corresponding to voting in favor of the phase-out initiative, voting against, and abstention. Table 6 contains the regression coefficients for the three contrasts: voting in favor versus against, voting in favor versus abstention, and voting against versus abstention. The coefficients of the third column are simply the result of subtracting the coefficients of the first column from those of the second.

The coefficients provide first clues with respect to the impact of the independent variables on voting behavior. Regarding the focal explanatory variable—exposure to newspaper coverage regarding the popular initiative—the results do not unambiguously support our first hypothesis. Contrary to what we had expected, exposure to increasingly positive tonality did not increase the probability to cast a “yes”-vote, at least in the contrast with voting “against” (first column). However, as can be seen from the coefficients in the second and third column, higher exposure to positive tonality led to a higher probability of casting a vote at all. While this finding seems counterintuitive in the case of rejecting the proposal, we conclude that positive coverage about the phase-out initiative generally had a mobilizing effect. Table 6 conveys some more interesting results. With respect to the government booklet, taking note of this publication had a mobilization effect, given that it significantly increased the probability to cast either a yes- or no-vote. Reading the booklet also significantly increased the probability of voting against, compared to voting in favor, which is hardly surprising given that the booklet advocated strongly against the popular initiative. With respect to partisan orientation, our model confirms that right-wing voters were significantly more likely to vote against the initiative. Moreover, both higher exposure to social voting cues and higher age operated in favor of participating in the vote but do not help explaining voting behavior as such. Finally, both the intention to vote in favor at t0 and the strength of the initial intention were significantly (and strongly) related to approval of the initiative at t1, while only the intention to reject the initiative (but not the strength of it) helps explain the mobilization of “no”-voters.

However, the results contained in Table 6 do not illuminate the ways in which the tonality of media reporting may have driven the three mechanisms introduced above. Therefore, in the next step, we computed predicted probabilities for different values of exposure to media coverage. We differentiated between voter segments corresponding to the mechanisms of reinforcement, demobilization and conversion in the following way:

-

Voters who were in favor of the initiative throughout (i.e., at t0 and t1): Reinforcement of support (n = 379)

-

Voters who intended to vote in favor of the initiative at t0 but did not vote: Demobilization of support (n = 77)

-

Voters who changed their preference from support (t0) to rejection (t1): Conversion of support (n = 148)

-

Voters who rejected the initiative at t0 and t1: Reinforcement of rejection (n = 324)

-

Voters who rejected the initiative at t0 but either did not vote (demobilization) or changed their preference to support at t1(conversion; n = 56).

We pooled demobilization and conversion for initial opponents because these two subgroups would become too small for meaningful quantitative analyses if included separately in our models. The remaining 30 voters who participated in both survey waves either had no preference at t0 or refused to indicate/did not remember their voting behavior at t1. As only three (nine) voters who had no initial voting intention finally supported (rejected) the phase-out proposal t1, we did not investigate potential activation effects.

Figure 6 shows predicted reinforcement, conversion, and demobilization effects for different values of the tonality index. For the computation of predicted probabilities, we converted the tonality index into five categories based on the quintiles of the distribution shown in Fig. 3: respondents exposed to strongly (1) or moderately (2) negative tonality about the phase-out initiative, respondents exposed to ambivalent tonality (3), and respondents exposed to moderately (4) or strongly (5) positive tonality. In line with our expectation (hypothesis 2), the probability of casting a “yes”-vote increased for left-party voters who intended to vote in favor at t0(n = 306), as we move from very negative (0.76) to very positive (0.95) tonality. Conversely, both the probability of demobilization (0.12 to 0.03) and conversion (0.12 to 0.02) significantly decreased, the more positive the newspaper coverage about the initiative became. Hence, positive media reporting played a significant role in fostering left-party voters’ initial voting intentions, and very negative reporting resulted in abstention or rejection of the initiative for a quarter of supporters of the political left who had initially intended to vote in favor. Looking at center/right-party voters with an initial intention to cast a “yes”-vote (n = 285), the pattern is different. Here, positive tonality did not lead to a reinforcement of initial intentions. Higher exposure to positive coverage even seems to have led to higher conversion rates (from 0.35 to 0.46), but the coefficients did not differ significantly from each other. Similar to voters of the left, tonality of newspaper reporting influenced the extent to which demobilization played a role: as we pass from a very negative (0.14) to a very positive (0.02) tonality, the probability to abstain from the vote significantly decreased. With respect to the groups of voters who opposed the proposal at t0(the lower panels in Fig. 6), little effects of newspaper coverage can be detected. For both supporters of left parties (n = 48) and of center/right parties (n = 326) with initial intentions to reject the initiative, exposure to an increasingly negative tonality tended to reinforce initial intentions, but none of these effects were statistically significant. We therefore reject hypothesis 3. While positive tonality tended to encourage demobilization or conversion for both groups of voters, these effects were also not statistically significant.

3.3 Discussion

Our analysis of voting behavior in the popular initiative on the nuclear phase-out yields three main results. With respect to reinforcement of initial voting intentions, we found a media effect for citizens leaning towards a party of the political left, but not for citizens leaning towards a party that opposed the proposal. For the latter, the tonality of newspaper reporting did not substantially influence whether they stuck to their original voting intentions or not, although exposure to very positive tonality was associated with somewhat weaker reinforcement among right-party voters with initial intentions to vote against the proposal. The cohesion of the political left, on the other hand, proved to be contingent on the tonality of newspaper coverage. While exposure to a (very) positive tonality towards the initiative engendered strong reinforcement of initial intentions, a (very) negative tonality was associated with significantly weaker reinforcement, with one in four left-wing voters who were exposed to strongly negative coverage during the “hot” campaign phase changing their initial voting intention. These voters either abstained from the vote or voted against. As we have shown elsewhere, an emphasis on the benefits of nuclear power (especially its better climate performance vis-à-vis imported coal power, which opponents of the initiative portrayed as the main alternative) may have caused many voters to rethink their initial preference.Footnote 52 Notwithstanding the deep partisan divide over nuclear power, which has recently been corroborated in a conjoint experiment by Dermont,Footnote 53 this finding suggests that the fundamental rejection of nuclear power is a less important part of the political DNA of the left than one may have assumed.

Second, in terms of demobilization, our multinomial logit model showed that exposure to positive tonality had a mobilizing effect. To put this finding into perspective, it needs to be highlighted that other variables including information sources such as the government booklet and social voting cues operated in favor of voter participation as well. What we deem worth to be emphasized, however, is that the more negative the tonality of media coverage about the initiative became, the less likely voters with an initial intention to cast a “yes”-vote were to participate in the vote. Given the rather low number of non-voters in our sample, future research should more closely investigate the role of media coverage in influencing turnout in the context of popular votes on energy topics and beyond.

Third, with respect to conversion, we found a significant effect of our exposure index for left-party voters but not for center- and right-wing voters. Nevertheless, as we showed in Fig. 5, many of the latter had initially supported the initiative but “defected” in the course of the campaign, voting in line with their preferred parties. Interestingly, they did this even when being exposed to newspaper coverage that was quite supportive of the initiative. Hence, while the tonality of newspaper coverage as such did not lead to conversion, it would be premature to conclude that the consolidation of the political right was independent of media coverage. As our regression analysis shows, partisan orientation was significantly related to voting behavior. This suggests that, for those voters, newspaper coverage in general may have helped them to learn about parties’ positions on the proposal, leading to an alignment of their voting intentions and general political predispositions.Footnote 54

To put the interpretation of results into context, two methodological issues should be noted. First, as is typically the case in applications of linkage analysis, the detected effects are very likely to represent lower-bound estimates of the true effects.Footnote 55 Given the high intensity of the campaign, the nuclear phase-out case can be seen as a most-likely case for identifying media effects in a referendum campaign,Footnote 56 which should have worked in favor of detecting any media effects at all. The fact that the effects are likely to be biased downwards is due to measurement limitations both in terms of media content analysis and media use. As a remedy, future studies on the role of media in citizens’ decision-making should consider using more fine-grained (beyond tonality scores at the article level) and encompassing (in terms of included media) measurements of media content. With respect to media use, recent work has proposed a range of sophisticated data collection techniques that may be more reliable than the self-reported media use queries used in this study.Footnote 57 Second, one may wonder whether voters’ decision to consume specific news media is an endogenous companion of socio-demographic characteristics and, most importantly, partisan orientation. To check for this possibility, we conducted a series of robustness analyses, including regressing the tonality index on the set of variables used in our main regression models as well as examining the average political leaning of readers of various newspapers. The main result of these analyses is that only geography, i.e., voters’ place of residence, is significantly related with consumption of specific newspapers. With respect to the partisan orientation of newspapers’ readership, we see differences for some newspapers, but these are overall quite small.

4 Conclusion

This chapter took a two-step approach. First, it investigated patterns of media coverage surrounding referendum campaigns in Swiss energy policy-making. Second, it asked to what extent the media have an effect on voters’ decisions at the ballot. As regards media coverage, we saw that media attention and tonality towards three recent energy policy votes followed some typical patterns in referendum coverage but also showed proposal-specific features. Compared to typical patterns, the media paid considerably more attention to the nuclear phase-out initiative and the Energy Strategy 2050, while much less attention was given to the initiative by the Green Liberals. In line with the finding that the media tend to reflect the political constellation surrounding a given proposal, tonality towards the Energy Strategy, a federal proposal, was indeed more positive than tonality towards the initiatives brought forward by challengers of the status quo. Interestingly, however, tonality towards the nuclear phase-out initiative was less negative than is typically the case for popular initiatives, leading to balanced coverage of the proposal. Apart from tonality, our findings highlighted different actor constellations. Through a combination of indicators (attention, tonality, actors), we came to the conclusion that media coverage of the nuclear phase-out initiative constituted a salient and politically well-known debate, boiling down to a left-right conflict typical of previous debates in the energy domain.

Following recent suggestions to study how voters’ acceptance of energy policies is formed by media coverage during political campaignsFootnote 58 and to combine media content analysis with survey research to examine the nexus between news media reporting and individual preference formation on nuclear power,Footnote 59 the second part of the chapter linked data on newspaper coverage of the phase-out initiative with a panel study. Using media content as a quasi-experimental stimulus allowed us to investigate the extent to which exposure to newspaper reporting had a bearing on changes in voting intentions among different groups of voters. Indeed, our analysis identified specific media effects regarding reinforcement and conversion of voting intentions and with respect to mobilization. While these effects were moderated by partisan orientation, they did not always play out as expected. Above all, for the important group of right-leaning voters who had initially supported the initiative but casted a “no”-vote, their vote choices were not contingent on their exposure to tonality as conveyed by newspapers. We concluded that media coverage affected voting behavior not only through its tonality (as for left-wing voters) but presumably through its volume (amount of media attention) and the cues on party positions, which future studies should more closely attend to. Again, we believe that these effects were issue- and proposal-dependent, given that popular initiatives usually receive a lot of support in their early stages but lose support as the campaigns go on. In this light, it would be interesting to examine media effects in the run-up to the vote on the Energy Strategy 2050, a much more “confusing” proposal from the perspective of citizens, as the center-right was itself divided. In general, combining manual content analysis of news articles provided by the monitor data with a panel survey in the context of a typical popular vote in Switzerland is a methodological innovation that should be taken up and refined in future research to even better understand the mechanisms through which media coverage helps voters to shape their vote choices on energy topics and beyond. Such an approach may also provide valuable insights into the dynamics of opinion formation in the context of local infrastructure siting decisions, most importantly perhaps in the context of wind turbine installations, where social acceptance risks and their roots need to be better understood and carefully managed in order to fulfill the goals of the ES2050.Footnote 60

Notes

- 1.

Throughout the text, we use the term “referenda” to refer to three distinct instruments of Swiss direct democracy: “popular initiatives” (popular votes launched by citizens to enact a constitutional amendment), “optional referenda” (popular votes to challenge a bill adopted by parliament) and “mandatory referenda” (popular votes on bills which by law have to be put on the ballot in any case).

- 2.

Kriesi (2012).

- 3.

- 4.

Hänggli (2012).

- 5.

- 6.

Hermann (2012).

- 7.

Gerth et al. (2012).

- 8.

Rademacher et al. (2012).

- 9.

- 10.

Hänggli (2012).

- 11.

Kriesi (2012), p. 232.

- 12.

For instance, Udris et al. (2018).

- 13.

Marquis et al. (2011).

- 14.

Marcinkowski and Donk (2012).

- 15.

Arlt et al. (2019) on the nuclear phase-out initiative.

- 16.

- 17.

The popular initiative on a “Green Economy” in the broader field of environmental policy also included some energy-related aspects. It was rejected in 2016.

- 18.

For instance, Udris et al. (2020).

- 19.

For instance, Udris (2016).

- 20.

- 21.

The 21 examined news outlets are listed alphabetically: 20 minuten; 20 minutes; 24-Heures; Aargauer Zeitung; Basler Zeitung; Berner Zeitung; Blick; Blick am Abend; Die Südostschweiz; Le Matin; Le Matin Dimanche; Le Temps; (Neue) Luzerner Zeitung; Neue Zürcher Zeitung; NZZ am Sonntag; Schweiz am Wochenende/am Sonntag; SonntagsBlick; SonntagsZeitung; Tages-Anzeiger; Tribune de Genève; Weltwoche.

- 22.

See Udris et al. (2018).

- 23.

Heidelberger (2017).

- 24.

Kristiansen (2017).

- 25.

Udris et al. (2018).

- 26.

See Duygan et al. (2021).

- 27.

- 28.

This is also supported by an analysis of the Statistical Office of the Canton of Zurich, available at https://statistik.zh.ch. Based on aggregate data on municipalities and voting results in these municipalities, Moser (2018), p. 3, finds that the vote can be explained much more on the economic dimension than on the cultural dimension.

- 29.

See Milic et al. (2014), p. 290 et seq. One reason is that this is exactly the period when citizens receive their voting material, which consists of the official ballots and accompanying official brochures on the content of the votes. There is evidence suggesting that many citizens cast their vote by postal ballot right after they receive the voting material.

- 30.

McCombs and Shaw (1972), p. 176.

- 31.

- 32.

- 33.

Lazarsfeld et al. (1944).

- 34.

Kriesi and Sciarini (2004).

- 35.

Selb et al. (2009).

- 36.

- 37.

Kriesi (2005).

- 38.

Dermont and Kammermann (2020).

- 39.

Miller et al. (1979).

- 40.

Scharkow and Bachl (2017).

- 41.

- 42.

While opt-in panels consist of a self-selected sample of volunteers, Intervista’s actively recruited panel comes close to a probability sample of the Swiss voting population. See https://www.intervista.ch/en/panel.

- 43.

The Italian-speaking region of Switzerland, in which only 6.1% of Swiss voters reside, was not covered by the survey.

- 44.

More information on the survey data can be found in Rinscheid and Wüstenhagen (2018).

- 45.

Bonfadelli and Friemel (2012).

- 46.

The categories are: spouse/partner; own children; own parents; other relatives; friends; neighbors; workmates; acquaintances from clubs, associations or congregations.

- 47.

Art. 3 para. 1 let. b Emergency Protection Ordinance (Verordnung über den Notfallschutz in der Umgebung von Kernanlagen, Notfallschutzverordnung, NSFV, SR 732.33).

- 48.

Bonfadelli and Friemel (2012), p. 174.

- 49.

See Milic et al. (2014), p. 299.

- 50.

See also the contribution by Schaffer and Levis (2021) in this volume, which underscores the particularly prominent role of newspapers in shaping public opinion compared with other news media.

- 51.

Our survey overestimates voter turnout (88.6% vs. 45.3% in reality). Such turnout gaps are a phenomenon typical of post-election studies, and the magnitude of the gap in our data is similar or slightly higher than turnout gaps documented in panel studies in the context of other Swiss referenda (Hänggli et al. 2012). The reasons are threefold: besides overrepresentation of politically interested citizens in political surveys and vote misreporting (Selb and Munzert 2013), politically active citizens are more likely to participate in a multi-wave survey (Sciarini and Kriesi 2003). One implication is that the numbers representing “voting behavior” in Fig. 5 are not representative of the entire electorate.

- 52.

Rinscheid and Wüstenhagen (2018).

- 53.

Dermont (2019).

- 54.

On this argument, see Selb et al. (2009).

- 55.

Scharkow and Bachl (2017).

- 56.

Sciarini and Tresch (2011).

- 57.

For an overview, see De Vreese and Neijens (2016).

- 58.

Carattini et al. (2017).

- 59.

- 60.

See Ebers Broughel and Wüstenhagen (2021).

References

Arceneaux K (2008) Can partisan cues diminish democratic accountability? Polit Behav 30:139–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-007-9044-7

Arlt D, Rauchfleisch A, Schäfer MS (2019) Between fragmentation and dialogue. Twitter communities and political debate about the Swiss “Nuclear Withdrawal Initiative”. Environ Commun 13:440–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1430600

Bonfadelli H, Friemel TN (2012) Learning and knowledge in political campaigns. In: Kriesi H (ed) Political communication in direct democratic campaigns. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, pp 168–187

Carattini S, Baranzini A, Thalmann P, Varone F, Vöhringer F (2017) Green taxes in a post-Paris world: are millions of nays inevitable? Environ Resour Econ 68:97–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-017-0133-8

De Vreese CH, Neijens P (2016) Measuring media exposure in a changing communications environment. Commun Methods Meas 10:69–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2016.1150441

De Vreese CH, Boukes M, Schuck A, Vliegenthart R, Bos L, Lelkes Y (2017) Linking survey and media content data: opportunities, considerations, and pitfalls. Commun Methods Meas 11:221–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2017.1380175

Dekavalla M (2016) Framing referendum campaigns: the 2014 Scottish independence referendum in the press. Media Cult Soc 38(6):793–810. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715620929

Dermont C (2019) Environmental decision-making: the influence of policy information. Env Polit 28:544–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1480258

Dermont C, Kammermann L (2020) Political candidates and the energy issue: nuclear power position and electoral success. Rev Policy Res:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12374

Duygan M, Kachi A, Oeri F, Oliveira TD, Rinscheid A (2021) Energy policymaking in Switzerland. In: Hettich P, Kachi A (eds) Swiss energy governance. Springer, New York

Ebers Broughel A, Wüstenhagen R (2021) The influence of policy risk on Swiss wind power investment. In: Hettich P, Kachi A (eds) Swiss energy governance. Springer, New York

Ettinger P, Imhof P (2014) Qualität der Medienberichterstattung zur Minarett-Initiative. In: Scholten H, Kamps K (eds) Abstimmungskampagnen. Springer VS, Wiesbaden, pp 357–369

Fazekas Z, Larsen EG (2016) Media content and political behavior in observational research: a critical assessment. Br J Polit Sci 46:195–204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000712341500006X

fög – Forschungsinstitut Öffentlichkeit und Gesellschaft / UZH (2019) Jahrbuch Qualität der Medien 2019: Schweiz – Suisse – Svizzera, Jubiläumsausgabe. Schwabe, Basel

Gerth MA, Dahinden U, Siegert G (2012) Coverage of the campaigns in the media. In: Kriesi H (ed) Political communication in direct democratic campaigns. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, pp 108–124

Hänggli R (2012) Key factors in frame building: how strategic political actors shape news media coverage. Am Behav Sci 56:300–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211426327

Hänggli R, Schemer C, Rademacher P (2012) Design of the study: an integrated approach. In: Kriesi H (ed) Political communication in direct democratic campaigns. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, pp. 39–53

Heidelberger A (2017) APS-Inserateanalyse der eidgenössischen Abstimmung vom 21. Mai 2017. Année Politique Suisse, Institut für Politikwissenschaft, University of Bern. Available at https://anneepolitique.swiss

Hermann M (2012) Das politische Profil des Geldes: Wahl- und Abstimmungswerbung in der Schweiz. Forschungsstelle sotomo am Geographischen Institut UZH, Zurich

Jandura O, Udris L (2019) Parteigänger oder neutrale Berichterstatter? Die Berichterstattung in Schweizer Printmedien vor den eidgenössischen Abstimmungstagen. MIP – Mitteilungen des Instituts für Deutsches und Internationales Parteienrecht und Parteienforschung 25:111–120

Kepplinger HM, Lemke R (2016) Instrumentalizing Fukushima: comparing media coverage of Fukushima in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland. Polit Commun 33:351–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1022240

Kriesi H (2005) Direct democratic choice: the Swiss experience. Lexington Books, Lanham

Kriesi H (2012) Conclusion. In: Kriesi H (ed) Political communication in direct democratic campaigns. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, pp 225–240

Kriesi H, Sciarini P (2004) The impact of issue preferences on voting choices in the Swiss Federal Elections, 1999. Br J Polit Sci 34:725–759. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123404000269

Kristiansen S (2017) Media and risk: a phase model elucidating media attention to nuclear energy risk. NEU - Nachhaltigkeits-, Energie- und Umweltkommunikation, vol 5. Universitätsverlag Illmenau, Illmenau

Kristiansen S, Bonfadelli H, Kovic M (2016) Risk perception of nuclear energy after Fukushima: stability and change in public opinion in Switzerland. Int J Public Opin Res 28:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edw021

Kübler D, Kriesi H (2017) Debate how globalisation and mediatisation challenge our democracies. Swiss Polit Sci Rev 23:231–245. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12265

Lazarsfeld PF, Berelson B, Gaudet H (1944) The People’s choice. How the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign. Columbia University Press, New York

Marcinkowski F, Donk A (2012) The deliberative quality of referendum coverage in direct democracy. Javn - Public J Eur Inst Commun Cult 19:93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2012.11009098

Marquis L, Schaub HP, Gerber M (2011) The fairness of media coverage in question: an analysis of referendum campaigns on welfare state issues in Switzerland. Swiss Polit Sci Rev 17:128–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1662-6370.2011.02015.x

McCombs ME, Shaw DL (1972) The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opin Q 36:176–187

Milic T, Rousselot B, Vatter A (2014) Handbuch der Abstimmungsforschung. Verlag Neue Zürcher Zeitung, Zurich

Miller AH, Goldenberg EN, Erbring L (1979) Type-set politics: impact of newspapers on public confidence. Am Polit Sci Rev 73:67–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/1954731

Moser P (2018) Die Abstimmungen vom 10.6.2018 - eine Kurzanalyse. Zurich. Available at https://statistik.zh.ch

Nicholson SP (2012) Polarizing cues. Am J Pol Sci 56:52–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00541.x

Rademacher P, Gerth MA, Siegert G (2012) Coverage of the campaigns in the media. In: Kriesi H (ed) Political communication in direct democratic campaigns. Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills, Basingstoke, pp 93–107

Renwick A, Lamb M (2013) The quality of referendum debate: the UK’s electoral system referendum in the print media. Elect Stud 32:294–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.10.013

Rinscheid A (2020) Business power in noisy politics: an exploration based on discourse network analysis and survey data. Polit Gov 8(2). https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i2.2580

Rinscheid A, Wüstenhagen R (2018) Divesting, fast and slow: affective and cognitive drivers of fading voter support for a nuclear phase-out. Ecol Econ 152:51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.05.015

Schaffer L, Levis A (2021) Public discourses on (sectoral) energy policy in Switzerland. In: Hettich P, Kachi A (eds) Swiss energy governance. Springer, New York

Scharkow M, Bachl M (2017) How measurement error in content analysis and self-reported media use leads to minimal media effect findings in linkage analyses: a simulation study. Polit Commun 34:323–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2016.1235640

Sciarini P, Kriesi H (2003) Opinion stability and change during an electoral campaign. Int J Public Opin Res 15:431–453

Sciarini P, Tresch A (2011) Campaign effects in direct-democratic votes in Switzerland. Journal of Elections. Public Opin Parties 21(3):333–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2011.588334

Selb P, Munzert S (2013) Voter overrepresentation, vote misreporting and turnout bias in postelection surveys. Elect Stud 32:186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.11.004

Selb P, Kriesi H, Hänggli R, Marr M (2009) Partisan choices in a direct-democratic campaign. Eur Polit Sci Rev 1:155–172. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577390900006X

Tresch A (2008) Öffentlichkeit und Sprachenvielfalt. Medienvermittelte Kommunikation zur Europapolitik in der Deutsch- und Westschweiz. Nomos, Baden-Baden

Udris L, Eisenegger M, Schneider J (2016) News coverage about direct-democratic campaigns in a period of structural crisis. J Inf Policy 6:68–104. https://doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.6.2016.0068

Udris L, Eisenegger M, Schneider J (2018) Medienresonanz von Abstimmungsvorlagen im Vergleich. In: Kübler D (ed) Medien und direkte Demokratie. Schulthess, Zurich, pp 65–88

Udris L, Eisenegger M, Vogler D, Häuptli A, Schwaiger L (2020, in print) Reporting when the current media system is at stake. Explaining news coverage about the initiative on the abolishment of public service broadcasting in Switzerland. In: Tandoc EC, Jenkins J, Thomas RJ, Westlund O (eds) Critical incidents in journalism: pivotal moments reshaping journalism around the world. Routledge, New York

Wettstein M, Wirth W (2017) Media effects: how media influence voters. Swiss Polit Sci Rev 23:262–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12263

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rinscheid, A., Udris, L. (2022). Referendum Campaigns in Swiss Energy Policy. In: Hettich, P., Kachi, A. (eds) Swiss Energy Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80787-0_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80787-0_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-80786-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-80787-0

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)