Abstract

Person-centred care (PCC) is an increasing international priority and a shift in health systems orientation and development. Innovative models are required across Europe to prototype healthcare based on health promotion and PCC to improve healthcare quality and costs containment. Regardless of the type of intervention, investments will be required, and it will be essential to demonstrate the value created, comparing consequences and the associated costs. Independent of PCC intervention, we must consider different decision levels and stakeholders in the process. This work aims to focus on a broader perspective of health governance on PCC implementations, considering the need and importance of measurement systems (outcomes and costs) to support and evaluate innovative health service delivery models. It is necessary to have a global view of the entire system considering, from a health governance perspective, the different decision-making levels, the multiple stakeholders and the alignment of their interests. Value-Based Healthcare (VBHC), Value for Money (VfM) and economic evaluation provide concepts, methodologies, and tools that can be used to compare costs and consequences evaluating their impact on society. We need accurate outcomes and costs measurement systems and evaluation tools that can be incorporated in an organizational environment supporting organizational learning and interaction in exchanging knowledge and experience about implementation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Health governance

- Measurement systems

- Person-centred care frameworks

- Value for money

- Economic evaluation

- Value-based healthcare

- Costs

- Outcomes

1 Introduction

Ensuring that healthcare is person-centred is an increasing international priority and a shift in orientation in health systems and its development. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has promoted and supported this approach in its global strategy for people-centred and integrated health services, and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), also confirmed their strong support in these efforts [58]. This aim implies that services are organized around people needs and expectations to make them more socially relevant and responsive while producing better outcomes [87, 88]. Besides the active involvement of the different stakeholders, it also empowers people to have a more active role in their health with broader benefits to individuals and their families, health professionals, communities, and health systems [89].

There is evidence that Person-centred care (PCC) improves health outcomes, maintains health care quality, and helps cost containment [46]. It is also a breeding field for innovation [21, 37, 38, 60] that can improve coordination and access to health care and services [10, 75] and other effects to the whole system. According to Louw et al. [48], PCC practice brings with it a broad number of benefits for the patient (higher satisfaction, improved health and quality of care, additional preventive care, better functional performance, and increased engagement), for the healthcare system (better adherence to treatment, recommendations and follow-up visits, increased Efficiency of care, reduction of the number of hospitalizations and shorter hospital stays), and the clinician (more satisfaction, better time management, and fewer complaints from patients).

The development of specific frameworks to capture the PCC essence and healthcare processes and outcomes has been extended to both generic and field-specific care delivery approaches. In a critical review of literature related to PPC, Phelan et al. [63] identified several frameworks, some in specific fields—like dementia, older person services, and acute care settings [22, 30]—and other developed as generic frameworks—like the Santana et al. [72] framework based on Donabedian model for healthcare improvement, and the Person-centred Practice Framework [50,51,52] with the broadest applicability and which has been most extensively adopted. The frameworks cited in the review present examples used in different countries and that could be used as a roadmap for PCC implementation. However, all of these frameworks have strengths and limitations, and offer variable utility for healthcare practice.

Innovative models are required across Europe to prototype healthcare based on health promotion and PCC, including Health Labs development to improve healthcare quality and costs containment [46]. Nevertheless, in the context of managing constrained healthcare budgets while safeguarding equity, access and choice, governments face the challenge to strategically manage scarce resources by investing in interventions that provide the best health outcomes [7, 47, 57, 80]. Regardless of the type of intervention, investments will be required, and as such, it will be essential to demonstrate the value created, comparing consequences and the associated costs. Independent of the type of PCC intervention, sponsors, policymakers, and managers require evaluations that prove that the additional health care resources needed to make the procedure, service, or program available to those who could benefit from it are justified.

Value-Based HealthCare [64, 66], Value for Money [29, 78] and economic evaluation [19, 31] all provide concepts, methodologies and tools to look at costs and consequences. They also, reinforce accountability assuring that taxpayers’ and sponsors’ money is spent wisely and that the stakeholder’s interests are safeguarded [29, 41, 78, 80]. To use the different instruments provided from these approaches in PCC settings, a robust measurement approach is needed. Silva [77] mentioned that such an approach helps to understand the extent to which care is person-centred and helps to differentiate worthwhile initiatives. The investment in measures that help to assess whether health systems deliver what matters to people, and not only how much they cost, is being recognized as a meaningful action to reorient health systems to become more people-centred [58]. This approach is also extensible for the costs side. According to Kaplan et al. [43], the currently existing cost systems in healthcare rely on inaccurate and arbitrary cost allocations and provide little transparency to guide first-line care providers attempts to understand and change the proper drivers of their costs.

Based on the issues mentioned, this chapter aims to focus on a broader perspective of health governance on PCC implementations, considering the need and importance of measurement systems (outcomes and costs) to support and evaluate new innovative models of health service delivery.

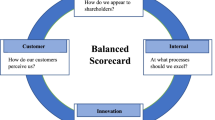

We start by introducing the concept of health governance and its different decision levels, using the Santana et al. [72] framework based on Donabedian model for healthcare improvement, and the VfM framework proposed by ICAI [41]. Taking these frameworks together, in our opinion, allows a global perspective of implementation, costs and consequences from a health governance point of view that can be applied at different levels of decision-making.

Next, we will look to the components of value according to Porter [64], measuring health outcomes that matter to patients and the cost of delivering the outcomes. Using several references, we will consider the importance of metrics on PCC, different types of person outcomes, and sources of measures, instruments and indicators that can be used to this end. Finally, we focus on the involved costs, namely different types and the difficulties in obtaining them, and possible solutions to get them in a more accurate way. We finish with a small real-life example of the application of a measurement framework, highlighting advantages and drawbacks.

2 Person-Centred Care Governance, Frameworks for Implementation and Value?

Health governance is defined as the actions and means adopted by society to organize itself to promote and protect its population’s health [17]. This approach devotes special attention to strengthening the capacity to formulate policies, develop good governance systems, set priorities at various levels, strengthen and broaden partnerships for health, and implement evaluation and monitoring [86]. Health governance encompasses different decision-making levels with distinct characteristics, each with its separate group of decision-makers, and interacting with each other in complex patterns. There are usually national government decisions determining the basic structure, organization and finance models of the entire health care system and the health organizations within it. Considering the different characteristics of health systems and countries’ various administrative autonomy levels for some policy decisions, the regional or local governments could also be involved. There is also decision-making at the overall institutional level of healthcare organizations. At a more micro level, it focuses on the day-to-day operational management of staff and services inside the health organizations.

The WHO [89] global strategy on integrated people-centred health services proposes five interdependent strategic directions: empowering and engaging people, strengthening governance and accountability, reorienting the model of care to more efficient and effective health care services, coordinating services around the needs of people at every level of care, enabling environment that brings together the different stakeholders to undertake the transformational change needed. This strategy means that a governance approach should be adopted to implement this global strategy at different levels. Although PCC must be implemented at the micro-level by care providers, PCC is also implemented at the meso (e.g., organizational) and macro (e.g., policy, organization and finance) service delivery levels of health systems.

One interesting framework that considers these different levels of implementation is proposed by Santana et al. [72]. The authors present a conceptual framework to guide systems and organizations in PCC provision and evaluation and health care quality improvement in general. This framework is based on the Donabedian [18] model domains of structure, process and outcome. It also encompasses different action levels (healthcare systems—organizations; patients—healthcare providers; patient—healthcare providers—healthcare systems) and identifies several constructs. Those elements are represented in Fig. 7.1 as domains, levels and constructs.

There is a strong emphasis on the structure because it provides the context, the decisions that shape the context, of care delivery. Seven constructs compose the structure: creating a PCC culture, developing and implementing educational and training programs to health workers, given support to workforce committed with PCC, providing a supportive environment, the development and integration of supporting health information technologies, and creating structures to measure and monitor and PCC. The process includes constructs related to communication, human and respectful care, engaging patients in their care, and integrating care. The outcome dimension focus on access to care (timely access to care, care availability, and financial burden) and several patient outcomes (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures—PROMs, Patient-Reported Experiences—PREMs, and Patient-Reported Adverse Outcomes—PRAOs).

The outcomes dimension proposed by Santana et al. [72] on the patient outcomes does not include a more recent source identified as data is patient-reported information (PRI) proposed by Baldwin et al. [6] that reinforce the patient perspective. For this reason, we included this category in the framework presented in Fig. 7.1.Footnote 1

The Santana et al. [72] framework is an interesting roadmap, starting in structural pre-requisite and ending in outcomes, guiding systems and organizations in PCC solutions, evaluating and health care quality improvement combining evidence, guidelines, and best practice from existing frameworks implementation case studies. However, despite mentioning costs from different perspectives (costs related to access, cost reduction, costs with transport and medication, etc.) it does not guide how to deal with this component and relate it to the consequences. This framework can be extended if we introduce value-based healthcare (VBHC), value for money (VfM), and economic evaluation throughout the cycle since they provide concepts, methodologies, and tools to look at costs and consequences evaluating their impact.

Porter [64] presented VBHC as a healthcare delivery model in which providers are paid based on patient health outcomes. The value is calculated by measuring health outcomes that matter to patients against the cost of delivering the outcomes [64, 66], considering the full cycle of care for a particular medical condition. Several countries have embraced this agenda [54], with varying types of implementation [79, 82], and their principles guide the quest for high-quality health care for acceptable costs in health systems [36]. Although no country has fully implemented the VBHC agenda, it seems apparent that different theoretical framework elements function better in some healthcare systems than others [54]. Some critics nevertheless present doubts about the VBHC guide claims about being the appropriate way forward, supported by the existence of multiple understandings of what value for patients means [55, 61] and little availability of evidence related to VBHC effectiveness [45]. Groenewoud et al. [36] reinforce these points of view and argue that a single-minded focus on VBHC may cause serious infringements on medical ethical principles.

Recently, the European Institute of Innovation & Technology (EIT) Health published a handbook on how to adopt VBHC initiatives (EIT [20] that propose an implementation model entitled the VBHC Implementation Matrix, which defines five key dimensions critical to most VBHC initiatives: recording (measuring processes and outcomes through a scorecard and data platform), comparing (benchmarking teams through internal and external reports), rewarding (investing resources and creating outcome-based incentives), improving (organizing improvement cycles through collective learning),and partnering (aligning internal forces and forging collaborations with external partners). Focusing on one specific condition is an essential first step to maximising the implementation success, followed by a clear identification of resources needed and related outcomes. There is a need to look at the entire cycle, starting on the primary inputs and finishing on the resulting impact.

VfM is about obtaining the maximum benefit with the resources available. One proposed framework to VfM, proposed by the Department for International Development (DFID’s) [41], is also included in Fig. 7.1. Their components are the input (staff, raw materials, capital), the process (the methods by which inputs are used), the outputs (what was delivery directly by agents), the outcome (what was achieved as a result), and the impact (long-term transformative change). The framework also compounds the four E’s and cost-effectiveness [29, 40]: Economy is about minimizing the cost of inputs while considering quality, Efficiency focuses on achieving the best rate of conversion of inputs into outputs, again taking into mind quality, Effectiveness relates to achieving the best possible result for the level of investment (not neglecting equity), Equity is about ensuring that benefits are distributed fairly. As we can see, these objectives may be conflicting, and care must be taken to prevent optimization conflicts. Cost-effectiveness emphasizes the ultimate impact of the policy, program or project relative to the inputs invested. VfM is a key factor to consider when planning policies, programmes and projects and when taking any decisions involving the use of public resources.

Several methods can be used to assess VfM [29]: Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CE analysis), Cost-Utility Analysis (CU analysis), Cost–Benefit Analysis (CB analysis), Social Return on Investment (SROI), Rank correlation of cost vs impact, and Basic Efficiency Resource Analysis (BER analysis). Some of these methods are common to generic economic evaluation. The primary purpose of economic evaluation is to inform decisions, so it deals with both inputs and outputs (costs and consequences) of alternative courses of action and is concerned with choices. The main types of economic evaluation studies are cost analysis (without identification or measurement of consequences), cost-effectiveness analysis, cost-utility analysis, and cost–benefit analysis [19].

Figure 7.1 combines the Santana et al. [72] framework for implementing PCC with the VfM framework for different assessment types considering all the value cycle from inputs to impact. This model thus allows a broad governance perspective of implementing PCC at various decision-making levels (macro, meso and micro). It also reinforces the importance of value from measuring health outcomes that matter to patients against the cost of delivering the outcomes. Finally, focus on the importance of obtaining the maximum benefit with the resources available proving to the different stakeholders (citizens, founders, policymakers, and managers) that the additional health care resources needed to make the procedure, service, or program available to those who could benefit from it are justified. It is essential to mention that this broad perspective of governance should be guided by the principles of good governance commonly identified in the literature, namely strategic vision, responsiveness, effectiveness and efficiency, accountability, transparency, equity and the rule of law [42, 84, 86]. The accountability of decision-makers (in government, the private sector and civil society organizations) to the public and stakeholders, and the transparency of processes, institutions and information, directly accessible to those concerned with them, and providing enough information to understand and monitor, are two core fundamental principles.

Any evaluation framework must also consider that the measurement system embraces two functions. The first is the act of the measurement itself, in other words, a technical activity consisting of “the assignment of numbers to observations” [14]. The second is the psychological effect the numbers exert on the employees who are responsible for the measured activities. Thus, measurement systems could be understood as “psycho-technical systems” [28].

Looking at the measurement system from the perspective of PCC implementation and functioning, medical organizations achieve their goals, when it delivers medical services better satisfying patients’ needs with greater efficiency and effectiveness than by “usual care”. Here the term effectiveness refers to the extent to which patients’ requirements are met, while efficiency is a measure of how economically the provider or healthcare system resources are utilized when providing a given level of patients well-being. To achieve the above goals, organizations have to influence employees in such a way that they will work according to the PCC framework. Although, organizations will provide appropriate training and resources they have to implement a measurement system to control whether established goals are achieved.

Generally, two elements can be measured, either directly the results of human work (e.g. how many gears were made by the miller during the working day) or human behavior (e.g. compliance of the procedure performed by the doctor with medical guidelines) [59]. Which element should be measured depends on the characteristics of the work performed. If the measurement of work performance can be precise and the task can be programmed, that is, there are no significant deviations during the work process, that means, the tasks are routine, then the measurement could be conducted based on an assessment of behavior or the final result of the work. On the other hand, when tasks become less programmable, that means, more stochastic, many non-standard situations may arise that require autonomous decisions based on many variables. In such a case, only the final result of the performed task can be used as the measurement strategy. For example, the car showroom owner is not interested in what actions the salesforce took and what techniques they use. What matters is how many cars they sold and at what price.

If the measurement of results is ambiguous, and the tasks are programmable, then the only available measurement strategy is the evaluation of behavior. For example, receptionists in a hospital. They have strictly defined routine tasks to perform, and the results of their work depend little on their actions, but on how many patients appear on a given day. However, what is important is their behavior, which means, whether they are not leaving their workplace, are polite, helpful and know the applicable procedures. It is important to state that behaviour is just one piece in the measurement puzzle because to have better organizations/systems we also need good decisions and information search and processing.

The problem appears, when both the measurement of results is ambiguous and the tasks are complex and non-programmable, then the measurement is rather impossible. In this case, employees’ behavior could be influenced through the implementation of social mechanisms, such as goal alignment, selection and socialization of employees. For example, the work of a team of surgeons in a trauma centre. In this action, the necessary behavior cannot be determined in advance, since it is not known what injuries the patient will suffer from. It is also impossible to determine how many patients a day they have to operate.

3 The Components of Value on PCC Implementations—Metrics, Outcomes and Costs

We need robust outcomes measurement approaches and costs determination to use the different instruments provided from VBHC, VfM and economic evaluation in PCC settings. Continually improving value requires better tools to assess both costs and benefits in health care [53]. These measurement systems are essential not only for decision support at different levels (macro, meso and micro), for evaluation (and inform decisions), and for management. From a management perspective, what is not measured cannot be managed or improved and, consequently, linking cost to process improvements or outcomes is difficult [65]. Using metrics to measure PCC can help drive the changes needed to improve the quality of healthcare that is person-centred [69].

Several authors recognize the difficulties associated with metrics and measures on PCC outcomes. Silva [77], states that there are many tools available to measure PCC, but no agreement about which tools most worthwhile and that currently there are no standardized mechanisms to measure and monitor PCC at a healthcare system level. In the same line, Pendrill [62] argues that there is no “silver bullet” or best measures covering all aspects of PCC. From a metrological point of view, there is a need to go beyond the traditional physical, chemical and biological quantities of clinical biomarkers to develop reference standards for novel kinds of quantities related to patient activity, participation and social well-being. Santana et al. [69] also point out that international efforts are being made towards the PCC model, but there are no standard mechanisms at a healthcare system level to measure and monitor PCC. The main conclusion is that a measuring instrument can be the best in one context and not so good in another, and there is a continuous need to ensure that quality indicators (often called psychometric indicators) are the most appropriate for the specific case.

There are several examples of international efforts to develop standard mechanisms. The OECD [58] recognizes as a meaningful action to reorient health systems to become more people-centred the need for investment in measures that help to assess whether health systems deliver what matters to people, and not only how much they cost. To fill in this gap, this international organization received a mandate from Health Ministers, to launch the Patient-Reported Indicators Surveys (PaRIS) initiative in 2017, to benchmark outcomes that matter most to patients (EIT [20]. Several other organizations, like the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM), the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT), and the Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement (COSMIN), The Health Foundation, and the Person-Centred Care Team also work on this field.Footnote 2

Metrics and measurement

The purpose of the measurement system is to influence human behavior to achieve organizational goals. The exploration of the literature suggests that there are four modes through which the act of measuring can influence people’s behavior at work [27, 28]. The first mode refers to the goals setting and their measures of achievement. In this mode, the measurement system serves as a criterion operationally defining the goals and standards of behavior or levels of targets (results) that should be achieved. In the context of PCC, this can relate to the establishment of targets of outcome or standards of behavior concerning the three genetic routines: initiating a partnership, shared decision-making; and safeguarding the partnership by documenting the person’s narrative and the jointly agreed care plan. The establishment of standards and targets simplifies the reality and, in this way, may have robust psychological effects. In other words, these standards and targets may provide a model of an appropriate set of variables to which actions should be adjusted and therefore focuses employees’ efforts and helps to organize thoughts and directions of analyzes.

The second mode is to mobilize managers and employees to systematic planning. Regular measurement of employees’ activity according to simplified criteria (predefined indicators or standards), catalyzes to increase both managers and employees planning efforts to achieve these predefined indicators or standards. Flamholtz [27] claims that measurement forces managers to think systematically about human resources value. They must anticipate future requirements for the workforce and their needs for training and development concerning the targets and standards they must accomplish. Additionally, managers have to assess the value of these tasks and standards to the organization’s success. In these circumstances, the numbers produced may not be as significant as the measurement process itself. This may suggest that measuring subjective constructs such as human resource value or compliance with PCC routines may not be a critical limitation. Although the measured numbers may be uncertain, the measurement process may strengthen systematic planning [27]. In this mode, the informative function of the measurement system may be regarded as a form of ex-post control as it allows the results achieved to be compared with the plan. On the other hand, when the measurement is used to indicate the expected level of achievement, it performs a planning-like function, influencing the behavior of employees while pursuing the assumed goals, therefore it can be considered an ex-ante control.

The third mode of the measurement system is to influence the perception of employees. The measurement system creates a set of information that serves as input and that generates alternatives for decision making and problem-solving. Therefore, decision and behavioral alternatives could be limited to the set of information generated by the measurement system.

The fourth mode of the measurement system affects both the direction and magnitude of the motivation. The presence or absence of performance measurements in a particular area affects employees’ behavior. Employees focus their efforts on areas where results or behavior is measured and ignore areas that are not being measured or rewarded. Measurement serves as a motivational function when information gathered about specific activities is used to evaluate an individual or group’s contribution and determine rewards [27, 32].

Information about achieved targets or the extent to the adherence to standards may also serve as a control mechanism. It can control employee behavior in an organization in two ways: directional and motivational. In the first, feedback information guides behavior by providing the information necessary for corrective action. In the second, it motivates behavior by serving as a promise of future benefits. In other words, the recipient of such feedback may use this information for corrective action, may interpret it as a reward or punishment, or may interpret it as a promise of future reward or punishment. This informative feedback function seems most appropriate in the context of a control system of employees. Extant studies suggest that the impact of feedback on results is positive when information is frequent, from a reliable source, timely, comprehensible, task-relevant, and specific [28].

Health outcomes that matter to patients

Several authors identify different types of outcome measures and tools that can be used in PCC settings. From a VfM and economic evaluation perspective, Gold et al. [31], Sorenson et al. [80], and Drummond et al. [19] identify clinical outcomes, quality of life measures, and generic health gain measures like Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), the Disability-Adjusted Life-Year (DALY), SF-36, EQ5D, and SF6D. The ECHOs model (Economic, Clinical, and Humanistic Outcomes) focus on economic outcomes and their interrelationships with the clinical and humanistic outcomes [13]. Other studies identify tools that can be applied to different actors and dimensions [46, 77] and quality indicators that can be used to measure PCC [67,68,69]. The explored framework from Santana et al. [71], presented in the previous section, considers as outcomes PROMs, PREMs, and PRAOs. We extended that framework by considering PRIs. Table 7.1 presents several sources of health outcomes, tools and instruments that can be used to evaluate PCC implementations.

Clinical outcomes are the most common health outcome category to be considered in clinical trials and observational studies. Some economic evaluations use these outcomes to measure health gain [19]. The humanistic outcomes are based on the patient perspective (e.g. reported scales that indicate pain level, degree of functioning) and include health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and the range of measures collectively described as patient-reported outcomes (PROs).

PROMs, are information provided by the patient about their symptoms, quality of life, adherence, or overall satisfaction [49, 85]. Data is collected by generic and disease-specific validated tools related to the quality of life (e.g. EQ-5D, AqoL), symptoms (e.g. NPRS for pain, FSS for fatigue), distress (e.g. K10 or PHQ2 for depression, GAD7 for anxiety), functional ability (e.g. WHODAS 2.0, ODI), self-reported health status (e.g. SF-36), or self-efficacy (e.g. GSE). Those tools collect patient ratings about several outcomes (health status, health-related quality of life, symptoms, functioning, satisfaction with care, or treatment satisfaction) or reports about their health behaviours, including adherence and well-being habits.

PREMs are tools and instruments that report patient satisfaction scores with health service [85] that are often used to capture health care’s overall patient experience. They are often used on the broader population and in non-specific settings such as an outpatient department, emergency services, or inpatient services. They are a reliable measure of how well health organizations can provide good quality service from a patient perspective on several dimensions: waiting time, access and ability to navigate services, involvement in decision-making, knowledge of the care plan and pathways, quality of communication, support to manage a long-term condition, or if they would recommend the service to family and friends.

PRAOs are related to adverse events and adverse outcomes [8]. The adverse events may be caused by all the aspects of care, including ameliorable adverse events (injuries whose severity could have been substantially reduced if different actions or procedures had been performed or followed) and preventable adverse events (injuries that could have been potentially avoided). The adverse outcome is any suboptimal outcome experienced by the patient, including a new or worsening symptom, an unexpected visit to a health facility, or death that can be identified by medical record review, discharge summaries, or through a patient interview. If the adverse outcome is captured latter, it is defined as PRAO. According to Barbara et al. [8], PRAO is any adverse outcome reported directly by the patient without interpretation of anyone else. Knowing patients’ perspectives and their relatives about quality and safety have become a priority, helping to build care processes centred on their users and improve clinical teams and organizations [56]. So, the perspective of PRAOs goes beyond the boundaries of health organizations and can be used in several fields like to improve the predictive accuracy of clinicians [9] or evaluate discharge communication for preventing death or hospital readmission [70].

PRIs are a more recent categorization of data proposed by Baldwin et al. [6] that upgrades the PRO tool reinforcing the patient’s perspective. This categorization considers the growing importance of social networks and how patients publish and receive communications easily and quickly. Social media has been used increasingly and more frequently by diverse stakeholders, including patients, to find information about diseases and treatments, and o to give support to patients and their caregivers. Schlesinger et al. [73] identified four forms of PRIs that can be used to improve clinical practice: patient-reported outcomes measuring self-assessed physical and mental well-being, surveys of patient experience with clinicians and staff, narrative accounts describing encounters with clinicians in patients own words; complaints/grievances signalling patients distress when treatment or outcomes fall short of expectations.

Lastly, it is essential to mention that from the previous section’s perspective, where we combine two frameworks, PCC implementation and value for money, that the different measures, tools, instruments and indicators can be used from different forms considering levels of decision-making, stakeholders and categories. For instance, Silva [77], from the UK’s Health Foundation, reviewed measurement tools targeted to different actors (carers, patients, professionals) and categories (carer experience, communication, dignity/empathy, engagement, patient experience, person-centred care, self-management support, and shared decision-making). From a quality perspective, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the MSI Foundation identified person-centred quality indicators related to structure, process, and outcomes [68, 69]. Using program theories (PTs), Lloyd et al. [46] identified seven different types of evidence-based PTs that could shape health laboratories’ design to implement PCC. It is possible to identify various qualitative and quantitative measures for the measurement/assessment that could be applied to diverse stakeholders and categories.

Costs of delivering the outcomes

Like outcomes, costs and their determination are crucial for VBHC, VfM and economic evaluation. In their first approaches to VBHC, Porter and Kaplan [65] claim that there is a complete lack of understanding of how much costs deliver patient care, and how these costs compare with achieved outcomes. According to them, poor cost systems have disastrous consequences, due to the difficulty of linking cost to process improvements or outcomes, leading to huge cross-subsidies across services with distortions in the supply and efficiency of care, and supplying wrong signals to providers, not rewarding adequately the effective and efficient ones, while providing inefficient ones little incentive to improve.

The accurate cost measurement in health care is a challenging issue. From a management accounting perspective, according to Young [90], healthcare organizations and health systems face various financial challenges related to economic pressures, health care reforms, and care demand that require an understanding of the costs associated with care delivery. The main forces that affect costs are demographic changes, with more ageing people, different spending patterns for older people, increasing morbidity in the nonelderly people, mainly related to cancer and heart disease, and the healthcare market’s complexity. These forces can be addressed by combining case mix and volume, resources per case, cost per resource unit, and fixed costs.

Porter and Kaplan (2011) also wrestle with the complexity of health care delivery, since treatment involves many various types of resources (human resources, equipment, technology, space and supplies) with different capabilities and costs. From admission to discharge, the patient pathway is diverse and depends on the initial medical conditions. The existence of non-standardized procedures (different procedures, drugs, devices, tests, and equipment for the same medical process) and the highly fragmented world of healthcare delivery, with different providers interventions, also contributes to this complexity.

According to Kaplan et al. [43], existing cost systems in healthcare rely on inaccurate and arbitrary cost allocation, while providing little transparency to guide first-line care providers in attempts to understand and change the proper drivers of their costs. They also argue that these systems prevent clinician-driven cost reduction and process improvement initiatives, proposing time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC) as one tool with significant potential to fill this gap. However, its application to healthcare has been limited. Some of the main advantages and disadvantages of the TDABC identified in the literature are presented in Table 7.2.

From a direct economic evaluation perspective, some considerations must be taken into account. Gold et al. [31] identifies costs related to changes: in the use of healthcare resources, in the use of non-healthcare resources, in informal caregiver time and in patient time (for treatment). By its turn, Drummond et al. [19], identifies health sector costs, other sector costs, patient/family costs, and productivity losses. Table 7.3 presents the different types of costs identified by those authors.

In a general way, authors identify categories of direct costs, indirect costs and intangible costs. Direct costs associated with providing the health service (fixed, variable, and non-medical expenses) are the easiest to calculate. Indirect costs related to decreased productivity due to the patient and his family’s disease or treatment are difficult to compute. Intangible costs (such as anxiety, pain or suffering with an illness) are extremely difficult or even impossible to determine.

The various perspectives presented here focus on the difficulty in determining the costs associated with healthcare interventions. If we adopt a VBHC perspective, we must considerer the full cycle of care for a particular medical condition [64, 66]. The VBHC definition applies to the entire care pathway, from primary care to tertiary care, including post-hospital care of patients affected by single and multiple conditions. From this perspective, implementing costs measurement should be relatively straightforward for patients affected by only one condition. However, it will be much more complicated for patients affected by multiple conditions and a problem to organizations with various type of services and a higher level of complexity requiring substantial investments in more accurate cost systems.

4 The Person-Centred Care Approach to Family Caregivers Needs Assessment and Support in Community Care

It should be noticed that the effective use of assessment and measurement tools depends on the application domain and their peculiarities. We will now show an application of an assessment tool (CSNAT) created to support community care for palliative care.

Community nurses play an essential role in providing palliative care for the patients, family and friends who support them at home. A unique role of providing community care to terminally ill persons mostly for several years have family members, friends, and/or neighbours. Those persons are in literature known as family caregivers or carers. Family caregivers or carers are the persons who operate home-based care with very complex medical and therapeutic tasks which are unpaid and have not formal training to provide those services. They act like an “arm extension” for providing care to terminally ill persons in the healthcare system.

Many factors hinder the proper identification and assessment of family caregiving support’s need to facilitate access to appropriate resources. Assessment of family caregivers supports needs usually have an ad hoc manner, informal and undocumented without comprehensive consideration needs and family carer problems. Caregivers usually focused on the needs and issues of patients. Home-based family caregiving terminal ill patients can significantly impact emotional, social, and physical cost caregivers and increase their mortality [5, 33, 74, 81]. Studies have shown that only early identification and better carers’ experience leads to better health outcomes in the longer-term, leading to reduced caregivers’ morbidity and mortality [2, 26, 34].

The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) is an evidence-based tool for the comprehensive assessment of carers’ needs, in a systematic way instead of an ad hoc manner [25]. This support tool for family carersFootnote 3 validated in UK CSNAT was developed to use in palliative care and adopts a screening format. The tool has a screening format structured around 14 broad support domains [25]. These domains fall into two distinct groupings, including: (1) those to enable a family carer to care at home,and (2) enable more direct support for themselves in a caring role (Table 7.4) [25]. The tool is practical brief from one side. From the other side, it is comprehensive, allowing the family to carer to identify priority domains that need further support, which can be discussed with providers (community nurse). Caregivers support cares in their primary role of caring, and their support needs will be identified by care providers.

The CSNAT is a five-step (Table 7.5) approach in person-centred care and care-led. For the appropriate use and implementation of this tool, changes must be made in existing practice, and practitioners need to shift their role from practitioner-led to practitioner-facilitated.

Benefits of the CSNAT approach

The CSNAT was used in numerous research studies and these showed benefits for practitioners and carers. The CSNAT’s was trialled in several studies in Western Australia [1, 2, 4] achieving overall positive practitioners feedback on using the CSNAT. Similar results have been obtained in a study that aims to assess the feasibility and relevance of CSNAT for home-based care at family caregivers of people with motor neurone disease (MND) [3]. This study was conducted in Perth (Western Australia). The family caregivers and advisers found that CSNAT approach is relevant and acceptable for the patient with MND in home-based care. This study also confirmed previous studies that used CSNAT approach about the comprehensive and formalized compared to standard practice. It was the first example of applying the CSNSAT approach in MND settings, which was different from the approach developed in the United Kingdom, and from the further trials in Australia in home-based palliative care settings. These caregivers identified and addressed three of five priorities to support, mainly priorities related to direct carer support such as knowing what to expect in the future, dealing with feelings and worries and having time for themself. In this study, for the caregivers, high priority was expressed for the knowledge of whom to contact if he/she feels concerned and needs care equipment.

A stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial was conducted in Australia, which aimed to investigate the impact of using the CSNAT on family caregivers’ outcomes such as strain, distress and mental and physical health, and describing investigation strategies [1]. This study showed that the mean (0.08) reduction in caregiver strain in the intervention group compared to the control group increased by 0.09 after adjusting for covariates. Means difference between an investigation and compared groups related to distress were not statistically significant. There was a small difference in secondary outcome (mental and physical wellbeing), but those differences were not statistically significant among groups. In both groups showed an increase in caregivers workload assisting with daily activities of daily living, but this increase was smaller and was not statistically significant. In the implementation strategy, caregivers put on the top four support needs, such as knowing what can expect in the future, having time for themselves in the day, dealing with their feelings and worries, and understanding the relatives’ illness.

A trial with family caregivers of older people discharged home from the hospital showed that family caregivers in the intervention group were significantly more prepared to provide care and reported reduced carer strain and distress than family caregivers in the control group [83].

Barriers and facilitates in implementing of the CSNAT approach

Implementation of CSNAT represents a challenge for the practitioners. Implementing it can block due to various barriers: practitioners’ beliefs and attitudes, lack of knowledge or training, and lack of time or resources [39]. The barrier can also be the number of practitioners ready to adopt the implementation of the new tool. According to the evidence, the number of adopters grows with a high proportion of internal facilitators among the staff members [16]. Training and giving the authority to the internal team facilitator is also an essential factor in the implementation process’s success, as is recognizing the crucial role of carers in providing home-based care for terminally ill patients, which also need to be enabled and supported by the clinical, managers, educators, and policymakers. In terms of health system governance, another barrier is the lack of visibility of this full-time work in society and the usual lack of recognition by the government initiatives and policies. Recommendations regarding the CSNAT approach suggested that the tool should form the basis of carer needs assessment, rather than an add-on to current practice [11].

5 Conclusion

When dealing with PCC interventions, it is necessary to have a global view of the entire system considering, from a health governance perspective, the different levels of decision making, the multiple stakeholders and the alignment of their interests. As mentioned before, although PCC innovations are implemented at the micro-level by care providers, they also are implemented at the organizational level (meso) and at a higher level (macro) by structural decisions that affect the shape of the entire health system. We also need to evaluate the impact of these innovative models on the whole society. VBHC, VfM and economic evaluation provide concepts, methodologies, and tools that can be used to compare costs and consequences evaluating their impact. Still, we need accurate outcomes and costs measurement systems.

The effectiveness of the measurement system’s influence on the behaviour compliant with the PCC routines may depend mainly on the adequacy and reliability of the information generated by the measurement system. In this context, adequacy of a measurement system refers to the extent to which the measurement process leads to the employees’ behavior supporting the PCC routines. While reliability refers to the extent to which the behaviours formed by the measurement process are consistently repeated. That means, that in many circumstances regardless of other factors, the measurement process motivates employees to follow the PCC approach.

As an important facilitator for practitioners in implantation, an evaluation tool should provide education on evidence-based knowledge, and be incorporated in an organizational environment which supports organizational learning and interaction in exchanging knowledge and experience about implantation.

Notes

- 1.

The concepts of PROMs, PREMs, PRAOs and PRIs will be expanded in the next section.

- 2.

A more detailed table will be presented in the topic “Health outcomes that matter to patients”. While the table contains specific examples for some areas, like rheumatology, other examples exist for other clinical specialties.

- 3.

This tool is oriented to family carers. In the field of informal care, the carer is not always a patient’s relative, however we kept the tool’s nomenclature.

References

Aoun, S., Deas, K., Toye, C., Ewing, G., Grande, G., Stajduhar, K.: Supporting family caregivers to identify their own needs in end-of-life care: qualitative findings from a stepped wedge cluster trial. Palliat. Med. 29, 508–517 (2015)

Aoun, S., Toye, C., Deas, K., Howting, D., Ewing, G., Grande, G., Stajduhar, K.: Enabling a family caregiver-led assessment of support needs in home-based palliative care: potential translation into practice. Palliat. Med. 29, 929–938 (2015)

Aoun, S.M., Deas, K., Kristjanson, L.J., Kissane, D.W.: Identifying and addressing the support needs of family caregivers of people with motor neurone disease using the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool. Palliat. Support. Care 15, 32–43 (2017)

Aoun, S.M., Grande, G., Howting, D., Deas, K., Toye, C., Troeung, L., Stajduhar, K., Ewing, G.: The impact of the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) in community palliative care using a stepped wedge cluster trial. PLoS One 10, e0123012 (2015)

Aoun, S.M., Kristjanson, L.J., Currow, D.C., Hudson, P.L.: Caregiving for the terminally ill: at what cost? Palliat. Med. 19, 551–555 (2005)

Baldwin, M., Spong, A., Doward, L., Gnanasakthy, A.: Patient-reported outcomes, patient-reported information. Patient 4, 11–17 (2011)

Banke-Thomas, A., Nieuwenhuis, S., Ologun, A., Mortimore, G., Mpakateni, M.: Embedding value-for-money in practice: a case study of a health pooled fund programme implemented in conflict-affected South Sudan. Eval. Program Plann. 77, 101725 (2019)

Barbara, O., Jose, S.M., Jayna, H.-L., Ward, F., Maeve, O.B., Deborah, W., Wrochelle, O., Ghali, W.A., Forster, A.J.: A framework to assess patient-reported adverse outcomes arising during hospitalization. BMC Health Serv. Res. 16, 357 (2016)

Basch, E., Bennett, A., Pietanza, M.C.: Use of patient-reported outcomes to improve the predictive accuracy of clinician-reported adverse events. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 103, 1808–1810 (2011)

Bhattacharyya, O., Blumenthal, D., Stoddard, R., Mansell, L., Mossman, K., Schneider, E.C.: Redesigning care: adapting new improvement methods to achieve person-centred care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 28, 242–248 (2019)

Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool.: The CSNAT Approach: a person-centred process of carer assessment and support in palliative and end of life care (2016). Available from: http://csnat.org/files/2015/10/161111_The-CSNAT-Approach_general-use.pdf

Chen, A., Sabharwal, S., Akhtar, K., Makaram, N., Gupte, C.M.: Time-driven activity based costing of total knee replacement surgery at a London teaching hospital. Knee 22, 640–645 (2015)

Cheng, Y., Raisch, D.W., Borrego, M.E., Gupchup, G.V.: Economic, clinical, and humanistic outcomes (ECHOs) of pharmaceutical care services for minority patients: a literature review. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 9, 311–329 (2013)

Cohen, B.P.: Developing Sociological Knowledge: Theory and Method. Wadsworth Publishing Company (1989)

Crott, R., Lawson, G., Nollevaux, M.-C., Castiaux, A., Krug, B.: Comprehensive cost analysis of sentinel node biopsy in solid head and neck tumors using a time-driven activity-based costing approach. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 273, 2621–2628 (2016)

Diffin, J., Ewing, G., Harvey, G., Grande, G.: The Influence of context and practitioner attitudes on implementation of person-centered assessment and support for family carers within palliative care. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 15, 377–385 (2018)

Dodgson, R., Lee, K., Drager, N.: Gobal Health Governance: A Conceptual Review. Dept of Health & Development World Health Organization, Centre on Global Change & Health London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (2002)

Donabedian, A.: The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA 260, 1743–1748 (1988)

Drummond, M.F., Sculpher, M.J., Claxton, K., Stoddart, G.L., Torrance, G.W.: Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. Oxford University Press (2015)

EIT Health: Implementing Value-Based Health Care in Europe: Handbook for Pioneers (2020)

Ekman, I., Busse, R., Hoof, C.V., Klink, A., Kremer, J.A., Miraldo, M., Olauson, A., Rosen-Zvi, M., Smith, P., Swedberg, K., Törnell, J.: Healthcare innovations and improvements in a financially constrained environment - Strategy Plan and R&D Roadmap (WE Care Consortium). WE Care Consortium (2016)

Ekman, I., Wolf, A., Olsson, L.-E., Taft, C., Dudas, K., Schaufelberger, M., Swedberg, K.: Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: the PCC-HF study. Eur. Heart J. 33, 1112–1119 (2012)

El Alaoui, S., Lindefors, N.: Combining time-driven activity-based costing with clinical outcome in cost-effectiveness analysis to measure value in treatment of depression. PLoS One 11, e0165389 (2016)

Ewing, G., Austin, L., Diffin, J., Grande, G.: Developing a person-centred approach to carer assessment and support. Br. J. Community Nurs. 20, 580–584 (2015)

Ewing, G., Brundle, C., Payne, S., Grande, G.: The Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for use in palliative and end-of-life care at home: a validation study. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 46, 395–405 (2013)

Ferrario, S.R., Cardillo, V., Vicario, F., Balzarini, E., Zotti, A.M.: Advanced cancer at home: caregiving and bereavement. Palliat. Med. 18, 129–136 (2004)

Flamholtz, E.G.: Toward a psycho‐technical systems paradigm of organizational measurement. Decis. Sci. 10, 71–84 (1979)

Flamholtz, E.G., Das, T.K., Tsui, A.S.: Toward an integrative framework of organizational control. Acc. Organ. Soc. 10, 35–50 (1985)

Fleming, F.: Evaluation methods for assessing Value for Money (2013). Available from: http://betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/Evaluating%20methods%20for%20assessing%20VfM%20-%20Farida%20Fleming.pdf

Fors, A., Taft, C., Ulin, K., Ekman, I.: Person-centred care improves self-efficacy to control symptoms after acute coronary syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 15, 186–194 (2015)

Gold, M.R., Siegel, J.E., Russell, L.B., Weinstein, M.C., Russell, L.B.: Cost-effectiveness in Health and Medicine. Oxford University Press (1996)

Goncharuk, A.G., Lewandowski, R., Cirella, G.T.: Motivators for medical staff with a high gap in healthcare efficiency: comparative research from Poland and Ukraine. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage. 35, 1314–1334 (2020)

Grande, G., Stajduhar, K., Aoun, S., Toye, C., Funk, L., Addington-Hall, J., Payne, S., Todd, C.: Supporting lay carers in end of life care: current gaps and future priorities. Palliat. Med. 23, 339–344 (2009)

Grande, G.E., Farquhar, M.C., Barclay, S.I.G., Todd, C.J.: Caregiver bereavement outcome: relationship with hospice at home, satisfaction with care, and home death. J. Palliat. Care 20, 69–77 (2004)

Gregório, J., Russo, G., Lapão, L.V.: Pharmaceutical services cost analysis using time-driven activity-based costing: a contribution to improve community pharmacies’ management. Res. Social Adm. Pharm. 12, 475–485 (2016)

Groenewoud, A.S., Westert, G.P., Kremer, J.A.M.: Value based competition in health care’s ethical drawbacks and the need for a values-driven approach. BMC Health Serv. Res. 19, 256 (2019)

Health Innovation Network: What is person-centred care and why is it important? (2014)

Hernandez, S.E., Conrad, D.A., Marcus-Smith, M.S., Reed, P., Watts, C.: Patient-centered innovation in health care organizations: a conceptual framework and case study application. Health Care Manage. Rev. 38, 166–175 (2013)

Horseman, Z., Milton, L., Finucane, A.: Barriers and facilitators to implementing the Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool in a community palliative care setting. Br. J. Community Nurs. 24, 284–290 (2019)

ICAI: ICAI’s Approach to Effectiveness and Value for Money. Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI) (2011)

ICAI: DFID’s approach to value for money in programme and portfolio management: a performance review (2018)

Institute on Governance: Governance Basis - What is governance? Available from: https://iog.ca/what-is-governance/ (2021). Accessed 2021–02–10 2005

Kaplan, R.S., Witkowski, M., Abbott, M., Guzman, A.B., Higgins, L.D., Meara, J.G., Padden, E., Shah, A.S., Waters, P., Weidemeier, M., Wertheimer, S., Feeley, T.W.: Using time-driven activity-based costing to identify value improvement opportunities in healthcare. J. Healthcare Manage. 59, 399–412 (2014)

Keel, G., Savage, C., Rafiq, M., Mazzocato, P.: Time-driven activity-based costing in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Health Policy 121, 755–763 (2017)

Larsson, S., Lawyer, P.: Improving Health Care Value: The Case for Disease Registries. The Boston Consulting Group (2011)

Lloyd, H.M., Ekman, I., Rogers, H.L., Raposo, V., Melo, P., Marinkovic, V.D., Buttigieg, S.C., Srulovici, E., Lewandowski, R.A., Britten, N.: Supporting innovative person-centred care in financially constrained environments: the WE CARE exploratory health laboratory evaluation strategy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3050 (2020)

Lorenzoni, L., Murtin, F., Springare, L.-S., Auraaen, A., Daniel, F.: Which policies increase value for money in health care? (2018)

Louw, J.M., Marcus, T.S., Hugo, J.F.: How to measure person-centred practice-An analysis of reviews of the literature. Afr. J. Primary Health Care Family Med. 12, 1–8 (2020)

Mackinnon III, G.E.: Understanding Health Outcomes and Pharmacoeconomics. Jones & Bartlett Publishers (2011)

McCormack, B., McCance, T.: Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 56, 472–479 (2006)

Mccormack, B., Mccance, T.: Person-centred nursing: theory and practice. Wiley –Blackwell (2010)

McCormack, B., McCance, T.: Person-centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons (2016)

McGinnis, J.M., Olsen, L., Yong, P.L.: Value in Health Care: Accounting for Cost, Quality, Safety, Outcomes, and Innovation: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press (2010)

Mjåset, C., Ikram, U., Nagra, N.S., Feeley, T.W.: Value-Based Health Care in Four Different Health Care Systems. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery, 1 (2020)

Nilsson, K., Bååthe, F., Andersson, A.E., Wikström, E., Sandoff, M.: Experiences from implementing value-based healthcare at a Swedish University Hospital - an longitudinal interview study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 17, 169–169 (2017)

O’Hara, J.K., Reynolds, C., Moore, S., Armitage, G., Sheard, L., Marsh, C., Watt, I., Wright, J., Lawton, R.: What can patients tell us about the quality and safety of hospital care? Findings from a UK multicentre survey study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 27, 673 (2018)

OECD: Health Care Systems: Getting More Value for Money. Author Paris, France (2010)

OECD: Ministerial Statement - The Next Generation of Health Reforms: Ministerial Statement. OECD (2017)

Ouchi, W.G.: A Conceptual framework for the design of organizational control mechanisms. Manage. Sci. 25, 833–848 (1979)

Peek, C., Higgins, I., Milson-Hawke, S., McMillan, M., Harper, D.: Towards innovation: the development of a person-centred model of care for older people in acute care. Contemp. Nurse 26, 164–176 (2007)

Pendleton, R.: We won’t get value-based health care until we agree on what “value” means. Harvard Bus. Rev. 2, 2–5 (2018)

Pendrill, L.R.: Assuring measurement quality in person-centred healthcare. Meas. Sci. Technol. 29, 034003 (2018)

Phelan, A., Mccormack, B., Dewing, J., Brown, D., Cardiff, S., Cook, N.F., Dickson, C., Kmetec, S., Lorber, M., Magowan, R.: Review of developments in person-centred healthcare. Int. Pract. Dev. J. (2020)

Porter, M.E.: What is value in health care?. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 2477–2481 (2010)

Porter, M.E., Kaplan, R.S.: How to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harvard Bus. Rev. 4, 47–64 (2011)

Porter, M.E., Kaplan, R.S.: How to pay for health care. Harvard Bus. Rev. 94, 88–100 (2016)

Santana, M.-J., Ahmed, S., Lorenzetti, D., Jolley, R.J., Manalili, K., Zelinsky, S., Quan, H., Lu, M.: Measuring patient-centred system performance: a scoping review of patient-centred care quality indicators. BMJ Open 9, e023596 (2019)

Santana, M.-J., Manalili, K., Ahmed, S., Zelinsky, S., Quan, H., Sawatzky, R.: Person-centred Care Quality Indicators (2019). Available from: https://www.personcentredcareteam.com/s/PC-QIs_Monograph_Santana-et-al-2019.pdf

Santana, M.-J., Manalili, K., Zelinsky, S., Brien, S., Gibbons, E., King, J., Frank, L., Wallström, S., Fairie, P., Leeb, K., Quan, H., Sawatzky, R.: Improving the quality of person-centred healthcare from the patient perspective: development of person-centred quality indicators. BMJ Open 10, e037323 (2020)

Santana, M.J., Holroyd-Leduc, J., Southern, D.A., Flemons, W.W., O’Beirne, M., Hill, M.D., Forster, A.J., White, D.E., Ghali, W.A.: A randomised controlled trial assessing the efficacy of an electronic discharge communication tool for preventing death or hospital readmission. BMJ Qual. Saf. 26, 993 (2017)

Santana, M.J., Manalili, K., Jolley, R.J., Zelinsky, S., Quan, H., Lu, M.: How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expectations 21, 429–440 (2018)

Santana, M.J., Manalili, K., Jolley, R.J., Zelinsky, S., Quan, H., Lu, M.: How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expectations 21, 429–440 (2018)

Schlesinger, M., Grob, R., Shaller, D.: Using patient-reported information to improve clinical practice. Health Serv. Res. 50(Suppl 2), 2116–2154 (2015)

Schulz, R., Beach, S.R.: Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 282, 2215–2219 (1999)

Sharma, T., Bamford, M., Dodman, D.: Person-centred care: an overview of reviews. Contemp. Nurse 51, 107–120 (2015)

Siguenza-Guzman, L., Auquilla, A., van den Abbeele, A., Cattrysse, D.: Using time-driven activity-based costing to identify best practices in academic libraries. J. Acad. Librariansh. 42, 232–246 (2016)

Silva, D.D.: Helping Measure Person-Centred Care - A Review of Evidence About Commonly Used Approaches and Tools Used to Help Measure Person-Centred Care. The Health Foundation (2014)

Smith, P.C.: Measuring Value for Money in Healthcare: Concepts and Tools. The Health Foundation, London (2009)

Soderland, N., Kent, J., Lawyer, P., Larsson, S.: Progress Towards Value-Based Health Care. Lessons from 12 Countries. The Boston Consulting Group. Inc. (2012)

Sorenson, C., Drummond, M., Kanavos, P.: Ensuring Value for Money in Health Care: The Role of Health Technology Assessment in the European Union. WHO Regional Office Europe (2008)

Stajduhar, K.I., Funk, L., Toye, C., Grande, G.E., Aoun, S., Todd, C.J.: Part 1: home-based family caregiving at the end of life: a comprehensive review of published quantitative research (1998–2008). Palliat. Med. 24, 573–593 (2010)

The Economist Intelligence Unit: Value-based Healthcare: A Global Assessment Findings and Methodology (2016)

Toye, C., Parsons, R., Slatyer, S., Aoun, S.M., Moorin, R., Osseiran-Moisson, R., Hill, K.D.: Outcomes for family carers of a nurse-delivered hospital discharge intervention for older people (the Further Enabling Care at Home Program): Single blind randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 64, 32–41 (2016)

UNDP: Reconceptualising Governance. New York: Management Development and Governance Division Bureau for Policy and Programme Support - United Nations Development Programme (1997)

Verma, R.: Overview: What are PROMs and PREMs. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation (2016)

WHO: Good Governance for Health. Equity Initiative Paper No 14. Geneva: Department of Health Systems, World Health Organization (1998)

WHO: People at the Centre of Health care: Harmonizing Mind and Body, People and Systems. WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Manila (2007)

WHO: Primary Health Care Now More Than Ever. World Health Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization (2008)

WHO: WHO Global Strategy on People-centred and Integrated Health Services (2015)

Young, D.W.: Management Accounting in Health Care Organizations. Jossey-Bass (2014)

Yu, Y.R., Abbas, P.I., Smith, C.M., Carberry, K.E., Ren, H., Patel, B., Nuchtern, J.G., Lopez, M.E.: Time-driven activity-based costing to identify opportunities for cost reduction in pediatric appendectomy. J. Pediatr. Surg. 51, 1962–1966 (2016)

Acknowledgements

This publication is based upon work from COST Action “European Net-work for cost containment and improved quality of health care-CostCares” (CA15222), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology)

COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) is a funding agency for research and innovation networks. Our Actions help connect research initiatives across Europe and enable scientists to grow their ideas by sharing them with their peers. This boosts their research, career and innovation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Raposo, V., Antonić, D., Nova, A.C., Lewandowski, R.A., Melo, P. (2022). An Overview of Measurement Systems and Practices in Healthcare Systems Applied to Person-Centred Care Interventions. In: Kriksciuniene, D., Sakalauskas, V. (eds) Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Person-Centered Healthcare. Intelligent Systems Reference Library, vol 205. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79353-1_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-79353-1_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-79352-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-79353-1

eBook Packages: Intelligent Technologies and RoboticsIntelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)