Abstract

The stone industry plays an important economic role in Italy as well as worldwide, and its products are part of the construction sector for hard coverings. The relevance of these products led the European Commission to develop specific criteria for natural stone within the Ecolabel scheme for hard coverings. In order to provide environmental information and to establish and maintain their comparability, the eco-labelling schemes recognized the life cycle assessment (LCA) as a scientific method to be employed when describing the environmental performance of the products. In its current form, the European Ecolabel scheme only considers environmental impacts and overlooks significant social impacts, especially for the category of stakeholders most affected during the extraction and manufacturing phases: workers. The main purpose of this study is to define a set of social criteria to be added to the revised version of the European Ecolabel with reference to issues concerning natural stone covering products. In particular, according to the updated guidelines for the social life cycle assessment by UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative (2019), we have identified that the “health and safety” impact category as it relates to workers during the extraction and manufacturing phases of the products must be considered a priority. The results provide a set of criteria for the S-LCA inventory which should be added to the Ecolabel guidelines when assessing the natural stone covering sector. Integration of the social sphere with the results obtained from the LCA study would provide reliable and more complete information on the sustainability of the natural stone product.

This represents a first step towards the inclusion of similar criteria for other covering products.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The stone industry plays an important economic role in Italy and worldwide. In fact, the stone and marble industry is a sector that in certain geographical areas contributes to the local production and employment capacity.

In the global trade of natural stone (marble, granite, stone, travertine) in 2015, Italy ranked second worldwide (13.5%) after China, which holds the largest market share with 35.8% (Japan and other countries in the region are among its most important partners) (Table 1) [1, 2]. Italy, with its production areas covering highly specialized activities and extracted rock types, still plays a strategic role in the production and exportation of stone materials. In 2018, marble, travertine and alabaster products achieved high exports of around 402,685 tonnes [3, 4].

Natural stone is widely employed in the building and construction sector, in particular as a wall cladding material due to its attractiveness, durability and versatility [5].

Nevertheless, this sector has a negative impact on the environment and society as a result of the large amount of waste generated by extraction and processing (30–50% of the extracted gross quantity) [6], dust pollution linked to the extraction process and water pollution caused by cutting processes [7].

By the twentieth century, the location of mining sites had shifted from developed to developing countries, with two important consequences: firstly, the provision of less expensive raw materials from non-European Union countries led Europe to rely more on imports; secondly, the environmental and social impacts shifted to countries that are major producers where attention to sustainability issues is lacking, making sustainability assessment necessary.

The interest in social and ethical issues raised by a product along its life cycle is increasing, particularly in sectors such as raw material extraction and mining where there are potentially high health and safety risks for workers.

As far as natural stone is concerned, the Italian ornamental stone industry is one of the main producers worldwide.

In Italy, in 2015 alone, approximately 5.3 million tonnes of ornamental stone were produced; the regions with the highest number of quarries (20 or more) are Tuscany, Lombardy, Apulia and Veneto [8]. The quarries of Carrara in Tuscany, for example, provide most of the marble used in Italy and Europe for sculpture and other ornamental work, along with a large number of blocks, which are sent in raw or finished form to all parts of the world [9].

Given the importance of this sector, the social impact issue cannot be ignored. Data from the Italian National Institute for the Prevention of Accidents at Work (INAIL) [10] shows that the number of accidents and occupational diseases in the “Quarrying of ornamental and building stone, limestone, gypsum, chalk and slate (NACE 08.11) sector” is not insignificant.

Starting with statistical data collected on accidents at work in this sector from the INAIL database, this study aims to highlight the integration of social aspects of sustainability regarding natural stone within the Ecolabel scheme (ISO 14024:2018) into the current revision of the criteria for the Ecolabels of hard floor coverings (Commission Decision 2009/607/EC).

The main goal of this study is to identify the social hotspots and social impacts that should be added as assessment criteria in the revised Ecolabel scheme for natural stone coverings.

In order to achieve the above-mentioned aim, this study is divided into three parts:

-

(1)

Background of the social criteria considered in official documents, in literature and in the existing Ecolabel schemes (e.g. European Ecoflower) with particular attention to stone and hard surfacing and the field limitations of this study

-

(2)

Identification of the weaknesses of the natural stone sector as regards health risks and injuries to workers during quarrying and manufacturing processes, based on a review of the literature on work medicine and a survey of the statistical data relating to workers’ health – taking the database developed by the Italian National Institute for the Prevention of Accidents at Work (INAIL) as a reference and based on an investigation of the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB), which provides social risk data at sector and country level, focusing on the global risk to health and safety in both stone quarrying and manufacturing processes

-

(3)

Proposal of a set of criteria for S-LCA inventory for natural stone coverings

The social indicator set developed can serve both as a proposal for the Ecolabel criteria revision with a view to social considerations and as a guide on how to determine the sustainability performance of the hard coverings. Furthermore, a list of challenges and benefits for social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) implementation can be identified and presented to support the current revision of the Guidelines on Social Life Cycle Assessment [11].

2 Aims of the Study and Assumptions

The main reference in the social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) is represented by two important guidelines: those developed by UNEP [11] which define the S-LCA as a complementary method of life cycle assessment (ISO 14040, 2006) and the Handbook for Product Social Impact Assessment [12], which was developed over 3 years of work by the Roundtable for Product Social Metrics. Both methodologies – the second derived from the first – identify the main stakeholder groups: workers, users/consumers and local communities. For each of them, a set of impact categories and its relative indictors was proposed. According to the UNEP guidelines, few case studies can be identified, and one of the first concerns natural stone products [13, 14].

The literature review conducted some years ago by Hosseinijou et al. [15] on the integration of social aspects into a life cycle format for building materials counts nine papers as the most remarkable: O’Brien et al. (1996), Schmidt et al. (2004), Dreyer et al. (2006), Hunkeler (2006), Norris (2006), Weidema (2006), Reitinger et al. (2011), and Lagarde and Macombe (2013) and Jørgensen et al. (2008), which reviewed most of the current S-LCA literature.

Based on an overview of the social aspects identified in 12 major S-LCA sources of the literature, and in accordance with the social impact categories proposed in the UNEP guidelines, Siebert A. et al. [16] in a recent study applicable to wood-based production systems in Germany identified a set of 15 social aspects. Of these 15 aspects identified, it was estimated that the most used indicators in the 12 case studies are discrimination/equal opportunities, fair salary/wages, health conditions/health and safety, freedom of association and collective bargaining (Fig. 1).

Set of social aspects applied in S-LCA case studies identified by [12]

Social impacts in the mining sector appear to have been discussed for over 10 years. Mancini et al. [17, 18] deal with this type of problem by combining the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB), a global database that eases the data collection burden in S-LCA studies [19], with the social impacts in the mining sector documented in 12 references (9 scientific papers and 4 reports from international organizations). The SHDB, following the UNEP S-LCA guidelines, indicates the social risk of the main countries and sectors in the world. Not all the data from impact subcategories is contained in the SHDB, but there is enough to provide a good overview. The study divides the social impacts into positive and negative and checks which impacts are included in the Social Hotspots Database. Therefore, as a first step of the research, taking into account all the impacts considered, we selected only the negative ones dealt with by both multiple sources of literature and the SHDB, and specifically “negative health and safety impacts on workers” and “environmental impacts affecting social conditions and health”.

The Global Ecolabelling Network (GEN), established in 1995, is a non-profit association of Type I Ecolabel organizations and has members in several countries. To improve, promote and develop the Ecolabels of products and services globally and to enhance mutual trust and recognition among various reputable Type I Ecolabelling programmes in accordance with ISO 14024, the GENIUS framework was developed which, in addition to verifying that each programme “abides by ISO 14024 principles and is robust and trustworthy, the process can inspire your employees around a shared societal goal” (The Global Ecolabelling Network, 2017).

An analysis focused on the ecolabelling programme for hard coverings within GEN showed that a very small percentage of schemes evaluate the social issues and adopt social indicators related to the health and safety of workers.

One of the most pertinent Ecolabel schemes in this sense is Australia’s Good Environmental Choice Australia (GECA) for hard surfacing, which with the introduction of Section 10 on “social and legal requirements” includes criteria linked to aspects such as equal opportunities and the safety and protection of workers.

In light of the above and in accordance with the stakeholder categories and subcategories suggested by UNEP “Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products”, this study focuses on workers’ health and safety: “negative health and safety impacts on workers”.

3 Weaknesses of Natural Stone Sector

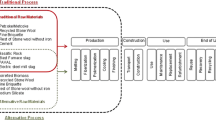

The natural stone extraction, transportation and manufacturing sector produces relevant environmental, social and economic impacts internally, locally and globally.

Guidelines for the safety of human health in the extraction industries were developed by the European Commission in Directive 2006/21/EC together with measures and procedures to reduce any adverse effects on the environment (in particular water, air, soil, fauna, flora and the landscape) within waste management.

References in literature show that non-European stone quarrying processes release elements into the environment such as dust, sludge or other industrial waste that may be toxic and constitute a health risk to humans: substances that are hazardous to the cardiorespiratory system, physical fitness and the body as measured at stone quarries [20, 21], pulmonary problems [22], skin dermatoses [23] and ocular health hazards [24], and in general the health of employees and their productivity and efficiency [25].

An analysis of occupational accidents in the mining sector in Spain, based on data from the Spanish Ministry of Employment and Social Safety between 2005 and 2015, shows that the most typical accidents are body movement involving physical effort or overexertion and, in underground mines, fractures, slips, falls or collapse. Moreover, it highlights that the lack of safety education and training is one of the most influential factors leading to mining injuries [26].

The INAIL database on reported work-related injuries in the quarrying of ornamental and building stone sector in Italy shows a fairly stable trend. In particular, this data shows that in the last 4 years, accidents at work have decreased by about 10%, while professional illnesses have increased by approx. 6% (Fig. 2).

Numbers of professional illnesses reported and accidents at work in the extraction of ornamental stone sector from 2015 to 2019 in Italy (elaborated by the authors from [10])

A more detailed analysis of the professional diseases classified according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, version 2010 (ICD-10), indicates that the four main burdens of disease are respectively diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99), diseases of the ear and mastoid process (H60-H95), disorders of the circulatory system (I00-I99) and diseases of the respiratory system (J00-J99). Specifically, Fig. 3 shows the number of workers with the diseases recorded from 2015 to 2019 and the average for each of the four main illness types.

Number of workers with the diseases classified according to ICD-10 from 2015 to 2019 in Italy (elaborated by the authors from [10])

4 Outcomes

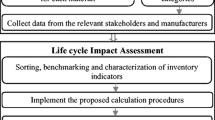

This study, which aimed to identify a set of social criteria to be added to the revised version of the European Ecolabel for natural stone covering products, has identified critical issues related to the social dimension through the following steps.

Starting with the screening of the five main stakeholder category groups (workers/employees, local community, society, consumers and value chain actors) to be considered in the social impact assessment in accordance with the UNEP guidelines (2009) and the revised version (2020) [11], we identified the priority of taking into account the health and safety aspects of workers who seem to be the most affected due to the intrinsic risks of the activities they perform during the extraction and manufacturing phases and their exposure to dust.

An initial review of work medicine literature relating to the issues arising in the natural stone industry was carried out, and we identified some recurrent and emerging diseases in addition to discomfort arising from occupational accidents and injuries.

Subsequently, we reviewed the social criteria already used in the flower scheme for products other than natural stone, and the results obtained from surveys on LCA studies filled in by companies in the natural stone sector.

We collected and analysed statistical data relating to workers’ health and injuries in the natural stone industry, limiting our study to Italian data. This survey showed that the principal issues are linked to the effect of the dust released into the workers’ environment during stone quarrying processes or within stone manufacturing phases, sludge production or other industrial waste processes workers come in contact with.

Finally, in order to highlight social hotspots in the mineral stone sector, we explored the SHDB in line with the outcomes highlighted by the last survey on the global risk to health and safety in both stone quarrying and manufacturing processes, and evaluated the risk levels related to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to airborne particulates in the workplace.

In conclusion, considering the results produced by this investigation from both work medicine literature and a survey of statistical data from the National Institute for the Prevention of Accidents at Work (INAIL), the main impacts are due to:

-

Dust emission with consequences for pulmonary and cardiorespiratory functions, as well as dermatologic and ocular diseases

-

The risk of accidents at work

-

The risk of accidents at work caused by contact with water and sludge which may be harmful to human health

In addition to these aspects, the outcomes from the INAIL statistics database show that the major cause of accidents is movements in the workplace that can result in muscular problems (Fig. 3).

On the basis of these observations, it is important to define and integrate social criteria related to workers’ health and safety in the natural stone coverings industry, to be added to the Ecolabel of these products. This would provide reliable and more complete information on their sustainable performance, as a first step towards the inclusion of similar criteria for other covering products.

5 Conclusion and Recommendations

These studies reveal the strong association between the environmental and social dimensions of the manufacturing processes. While the environmental dimension has been broached by voluntary methods to certify and label environmental performances, such as the Type 1 label (Ecolabel), social aspects were left out. Furthermore, no consideration was given to the fact that data and indicators to estimate local environmental impacts can also support the assessment of the social impacts related to health and safety. It should be noted that national regulations on the health and safety of workers are in place, but they are not included in product labelling.

The study we conducted shows that Type I Ecolabel statements should contain a more complete assessment and documentation of product sustainability. Our suggestion is that the inclusion of social criteria in the Ecolabel scheme is clearly necessary to avoid an incomplete assessment of the impact of the natural stone manufacturing process.

This work can be considered a first step in the process of identifying a set of social criteria related to the workers’ stakeholder category. The limitations of the study lie in the fact that we only analysed one of the important stakeholders closely involved in the social issue.

Therefore, future work should broaden the field of analysis for this proposal and investigation, first and foremost to the impacts of subcategories on “local communities”.

References

Montani, C. (2016). XXVII World marble and stones report 2016. Aldus Casa di Edizioni in Carrara.

U.S. Geological Survey, Mineral Commodity Summaries 2019. (2019). U.S. Geological Survey, 200 p. https://doi.org/10.3133/70202434.

https://stonenews.eu/italys-natural-stone-products-exports-2018/

Ferreira, C., Silva, A., de Brito, J., Dias, I. S., & Flores-Colen, I. (2021). Definition of a condition-based model for natural stone claddings. Journal of Building Engineering, 33, 101643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101643

Marras, G., Bortolussi, A., Peretti, R., & Careddu, N. (2017). Characterization methodology for re-using marble slurry in industrial applications. Energy Procedia, 125, 656–665.

Abu Hanieh, A., AbdElall, S., & Hasan, A. (2014). Sustainable development of stone and marble sector in Palestine. Journal of Cleaner Production, 84, 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.10.045

Zanchini E., e Nanni G. (2017). Legambiente – Rapporto cave, GF pubblicità – Grafiche Faioli.

Primavori, P. (2015). Carrara marble: A nomination for ‘Global Heritage Stone Resource’ from Italy. Geological Society London Special Publications, 407(1), 137–154.

https://bancadaticsa.inail.it/bancadaticsa/login.asp (Accessed 01.08.2019).

UNEP, Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations 2020. Benoît Norris, C., Traverso, M., Neugebauer, S., Ekener, E., Schaubroeck, T., Russo Garrido, S., Berger, M., Valdivia, S., Lehmann, A., Finkbeiner, M., Arcese, G. (eds.). United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2020

Fontes, J. et al. Handbook of product social impact assessment version 3.0, 2016. https://product-social-imocat-assessment.com (Accessed 02.08.2019).

UNEP/SETAC Life Cycle Initiative. (2011). Towards a life cycle sustainability assessment-making informed choices on products. Paris: United Nations Environment Programme.

Finkbeiner, M., Schau, E. M., Lehmann, A., & Traverso, M. (2010). Towards life cycle sustainability assessment. Sustainability, 2, 3309–3322. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/2/10/3309/pdf

Hosseinijou, S., Mansour, S., & Shirazi, M. (2014). Social life cycle assessment for material selection: A case study of building materials. International Journal Life Cycle Assessment, 19, 620–645.

Siebert, A., Bezama, A., O’Keeffe, S., & Thrän, D. (2018). Social life cycle assessment: In pursuit of a framework for assessing wood-based products from bioeconomy regions in Germany. The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment, 23(3), 651–662.

Mancini, L., Eynard, U., Eisfeldt, F., Ciroth, A., Blengini, G., & Pennington, D. (2018). Social assessment of raw materials supply chains. A life-cycle-based analysis, JRC Technical report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Mancini, L., & Sala, S.(2018). Social impact assessment in the mining sector: Review and comparison of indicators frameworks. Resource Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2018.02.002.

Benoit-Norris, C., Cavan, D. A., & Norris, G. (2012). Identifying social impacts in product supply chains: Overview and application of the social hotspot database. Sustainability, 4, 1946–1965. http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/4/9/1946/pdf

Swami, A., Chopra, V. P., & Maliket, S. L. (2009). Occupational health hazards in stone quarry workers: A multivariate approach. Journal of Human Ecology, 5(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/09709274.1994.11907078

Olusegun, O., Adeniyi, A., & Adeola, G. T. (2009). Impact of granite quarrying on the health of workers and nearby residents in Abeokuta Ogun State, Nigeria. Ethiopian Journal of Environmental Studies and Management, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.4314/ejesm.v2i1.43497

Nwibo, A. N., Ugwuja, E. I., Nwambeke, N. O., Emelumadu OF, & Ogbonnaya, L. U. (2012). Pulmonary problems among quarry workers of stone crushing industrial site at Umuoghara, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. International Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine, 3(4), 178–185.

Ugbogu, O. C., Ohakwe, J., & Foltescu, V. (2009). Occurrence of respiratory and skin problems among manual stone-quarrying workers. Mera: African Journal of Respiratory Medicine, 23–26.

Ezisi, C. N., Eze, B. I., Okoye, O., & Arinze, O. (2017). Correlates of stone quarry workers’ awareness of work-related ocular health hazards and utilization of protective eye devices: Findings in Southeastern Nigeria. Indian Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine, 21(2), 51–55. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijoem.IJOEM_171_16

Oginyi, R. C. N. (2010). Occupational health hazards among quarry employees in ebonyi state, Nigeria: Sources and health implications. International Journal of Development and Management Review (INJODEMAR), 5(1).

Sanmiquel, L., Bascompta, M., Rossell, J. M., Anticoi, H. F., & Guash, E. (2018). Analysis of occupational accidents in underground and surface mining in Spain using data mining techniques. International Journal of Environmentel Research Public Health, 15(3), 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030462

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Palumbo, E., Traverso, M. (2022). Social Life Cycle Indicators Towards a Sustainability Label of a Natural Stone for Coverings. In: Klos, Z.S., Kalkowska, J., Kasprzak, J. (eds) Towards a Sustainable Future - Life Cycle Management. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77127-0_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77127-0_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-77126-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-77127-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)