Abstract

Large-scale shantytown renovation initiated in 2005 has completely changed the living environment of lower-income residents in Chinese cities. It has also brought about great changes in the make-up of urban communities. Over 100 million people now live in newly renovated former shantytowns, creating a new type of community across China's cities and towns. This chapter summarises the evolutionary phases in this process, outlining the characteristics and the different models involved. It then uses research from field investigations into four models of shantytown reconstruction to consider changes in social mobility and levels of segregation within the reconstructed communities. It also establishes the more holistic features of these new communities as a model for future development and greater social integration. The process draws on the shared heritage—the ‘roots and souls’—of earlier communities and reshapes ‘shantytown removal’ in a more socially integrated way for the future development of Chinese urban society.

This paper is the phased achievement of the 2016 Key Project of the National Fund of Social Science “Research on Renovation of Large-scale Shantytowns and New Type of Community Construction” (Approval No.: 16ASH002.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Urban development follows a historically constant rhythm of rise and fall. Cities do not simply grow but also shrink and decline. Contemporary urban regression is mainly due to rapid changes in industrial structure. For instance, the economy of a rising industrial or mining city may suddenly decline as resources are exhausted, leading to structural and social decline. Faced with ‘Resource Curse,’Footnote 1 the process of urban development changes from one of peripheral growth into a standard development model that aims to improve the efficiency of urban interior space. The urban renovation strategy then shifts focus from revitalisation, improvement and micro-updating to the concurrent regeneration of older areas alongside the introduction of large, new development projects. Meanwhile, contemporary ideological trends that emphasise continuity with the traditional context, such as inclusive and sustainable development, encourage a more comprehensive approach. This includes both social innovation and economic renovation and takes community as the essential foundational factor. The contemporary approach to urban regeneration involves remodelling the quality of life, and re-establishing and re-constructing positive community relations. The renovation of China’s shantytowns is a successful example of contemporary urban regeneration in practice.

Most existing studies on urban renovation in China consider ancient big cities, such as old Beijing and the ‘three-olds’ (old towns, old factories and old villages) in Guangdong. Few studies cover shantytown renovation. From the perspective of traditional approaches to urban regeneration, the renovation of shantytowns is a lesser form of urban regeneration. Chinese urbanisation has grown at an unprecedented rate and scale since the 1970s. As the process continued into the present century, China began to optimise and upgrade the stock of urban buildings. This process has not only changed the urban architectural scene but also directly influenced social structures. The renovation of shantytowns has also dramatically changed urban communities. The typical classifications for Chinese communities were traditional: those connected with organisations, those consisting of commercial, residential houses, and those with a combination of organisationally run and commercial residential houses. These classifications correspond to the shift from a communist collectivist system to a market economy, with consequent changes in geo-social structures (Community Informatization Research Centre, Institute of Sociology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 2014; Li Guoqing, 2007). It represents a substantial and significant shift. When the shantytown renovation project nears completion in 2020, over a hundred million people will live in some 54 million newly renovated shantytown houses, accounting for about 10% of China’s total population. These newly renovated sites will undoubtedly form new communities within Chinese towns and cities.

Urban life is becoming more individualised on a global level, with enhanced administrative infrastructures developing to support this transition. In the case of the refurbishment of Chinese shantytowns, the government and residents made high demands for community sustainability and services. An emphasis on the role of the communities themselves in slum regeneration developed only gradually worldwide. Such communities were generally seen as passive social groups with limited active functions. UN-Habitat, in the 2003 report The Challenge of Slums: Global Report on Human Settlements noted a change in attitude towards the involvement of ‘folk society’ and rural dwellers in the improvement of living standards and the promotion of the democratisation process (UN-Habitat 2003, 190). The report emphasised that, collective management is also an important feature for the redevelopment of lower-income settlements at the broader, societal level. A series of working groups and organisations are typically established to realise such collective endeavours effectively. These could include everything from water supply and other utilities to health services, education, health services, security and crime control. Voluntary and non-profit making groups and associations are also an effective way to mobilise and empower women in the decision-making process.

In China, the government both coordinates and strongly promotes shantytown community engagement in the redevelopment of former shantytowns. The government provides residents with comprehensive social security through a two-way process of community engagement. Meanwhile, government agencies actively cultivate the ‘self-service’ capacity of community organisations to empower them to make their own decisions in post-shantytown renovation. These communities largely consist of low-income earners, unlike those living in collective or in commercial, residential properties. Residents are consequently faced with the important task of developing their quality of life. The community becomes a crucial ‘reciprocal platform’ for two-way engagement with the administrative authorities. Not only does the community cooperate with the administration to provide social security services, but also helps to shape and diversify the services they receive.

Various studies chart the transition from a communist collective system to more communal or grass-roots systems within a market economy (Sun Liping 2003) as the process unfolded, the responsibility for managing the social life of residential ‘units’ transferred to the communities themselves (Yipeng et al. 2014). The second phase involved the transition from ‘community management’ to ‘community governance’. At its heart was the empowerment of the public to participate in community affairs. Stakeholders were mobilised to form co-operative and mutual forms of governance and thereby invigorate social vitality (Qiang and Ying 2015). Hitherto, investigations into community structures were always derived from studies on system transition, social governance and organisational development. They lacked the awareness of problems with community structures as the standard, and lacked studies showing how to realise sustainable community development. As a result, they failed to develop a ‘discourse’ system centred on the community itself.

The social science disciplines have yet to fully explore and discuss these transitions. There is a dearth of studies of the preliminary stages of such developments and there is a need to clarify the relevant background information and knowledge required. To encourage this process, this chapter first briefly outlines the spatial–temporal characteristics of shantytown renovation. We then consider four types of shantytown to chart their formation, their separation from mainstream urban society, and various mechanisms for their renovation, development and integration as new forms of urban community. According to varied and complex historical processes and context, the four types of shantytowns shaped community characteristics in different ways. Strategies for spatial management and social governance and their impact on communities varied during the process of shantytown renovation. Nevertheless, the four shantytown models share many features in common. They are characterised by a drastic renovation of social and industrial infrastructures against a background of a shared tradition in the ‘communist collective system.’ There have been dramatic changes in both their original physical layout and structures as well as the geo-political structures of Chinese society during the era of market reform. The rich and complex process of historical development that affects these newly renovated shantytowns can be encapsulated into a single conceptual framework where lower-income settlements are transformed into new forms of urban community. The chapter concludes by comparing the varying abilities of these four types of community to establish a shared economic base and common consciousness. What is required is a transformation of the heart and soul of these shantytowns to integrate more fully with the future development of mainstream urban society. An understanding of this process will inform the emergence of new lower-income communities and settlements in China.

2 Phases and Features of Shantytown Renovation

Large-scale shantytown renovation in China started in Liaoning Province in 2005. As urban redevelopment gathered pace, shantytown renovations were initially undertaken as humanitarian projects to improve the living conditions of lower-income groups. With changes in domestic and foreign policies, it became a new engine to boost economic growth and promote urban regeneration. The process offered benefits across social, economic and urban developments.

2.1 Three Phases of Shantytown Renovation

Launch and exploration phase (2005–2008)

The process began with the regeneration of state-owned industrial and mining enterprises in Liaoning Province. Shantytowns developed as a result of insolvency and industrial decline across state-owned enterprises following restructuring in 1993 (Xiangfei and Chunyan 2010, 5:58). Under the previous communist collective system workers lived in accommodation connected to the industries that employed them. As state-owned enterprises closed, communities lost both vital services and geographical cohesion, the support structures they needed in daily life. This resulted in a breakdown in community cohesion and a deterioration in health and public order.

In early 2005, Liaoning Provincial Party Committee launched centralised and continuous regeneration projects throughout the province. These arose both in response to internal demand for urban development and direct government intervention to address social issues. The Party adopted a ‘five in one’ mechanism comprising party committee leadership, government promotion, social participation, enterprise support and community autonomy. By 2009 some 760,000 properties were undergoing continuous redevelopment, providing a model for state-owned industrial and mining shantytowns.

Transition from local to national policy (2008–2012)

The global financial crisis from September 2008 had a serious impact on Chinese exports. Economic growth declined sharply after a period of rapid and sustained growth. In response, the Chinese government introduced ten measures to expand domestic demand and promote economic growth. The first was to accelerate the construction of government-subsidised housing projects. In December 2009, five ministries, including the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development issued Instruction on Promoting Shantytown Renovation of Urban and State-owned Industrial and Mining Enterprises. This marked the formal launch of shantytown renovation projects nationwide. The relocation of shantytown residents comprised monetary and in-kind compensation, chosen voluntarily by each household, increased tax policy support, and reduced operating charges to reduce the renovation costs. In December 2009, the Datong Shantytown Renovation Work Conference extended the regeneration projects to state-owned forestry and reclamation areas.

In this period, a total of 12.6 million shanty dwellings were renovated nationwide. The government invested a total of RMB 150 billion, which has promoted investment and increases in household disposable income, and improved housing conditions among the preliminary results.Footnote 2

Comprehensive extension of shantytown renovation (2013–2017)

In 2013, the new Chinese government proposed the objective of renovating another 10 million houses across four categories of shantytowns in cities, state-owned industrial and mining areas, forestry areas and agricultural reclamation areas. In 2014, the central government established the ‘Three One-Hundred Million People’ policy, which included renovating urban shantytowns and villages in cities of around 100 million inhabitants. The regeneration of shantytowns became the strategic pillar of a new approach to urbanisation. To realise this aim, the regeneration of shantytowns must be fully accelerated. For this purpose, in 2015, the State Council launched an initiative to renovate some 18 million dwellings, including dilapidated houses and run-down urban areas between 2015 and 2017.Footnote 3

In February 2016, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued Several Opinions on Further Enhancing Construction and Management of Urban Planning. This confirmed that shantytown and housing improvements were the primary goals in enhancing urban public services. The three-year campaign of shantytown renovation should remain a core priority and be carried out fully as possible. According to this policy, in May 2017, the central government introduced a new three-year plan to renovate another 15 million shanty dwellings from 2018 to 2020 to complete the regeneration within that time scale.

2.2 Four Types of Shantytown Renovation

The National New Urbanization Plan (2014–2020) issued in 2014 divided shantytown renovation into four types: renovation of urban shantytowns and of state-owned industrial and mining shantytowns, renovation of state-owned forest-area shantytowns and renovation of dwellings in state-owned reclamation areas. The first mainly involved the inclusion of both shantytowns and ‘urban villages’ in the regeneration process. The second involved communities within the railway, steel, non-ferrous and gold industries. In the third category, eligible communities in forestry areas were included in the local urban housing security system alongside those from state-owned properties. Equally, in the fourth category, non-state-owned farms and properties were also uniformly included in the regeneration schemes.

2.3 Main Achievements in Shantytown Renovation

From 2005 to the end of 2014, a total of 20.8 million shanty dwellings were renovated in China.Footnote 4 During the six years from 2015 to 2020, the phase of the ‘Three One-Hundred Million People’ policy, some 33 million houses will be constructed. On the calculation that there are 3.02 people per household in China,Footnote 5 these could accommodate about 100 million people. When examining the achievements of this remarkable regeneration from the perspective of urban sociology, it becomes readily apparent that these newly renovated areas form a new category of the Chinese urban community. The full impact and value of this aspect of urban regeneration warrant further study.

3 Shantytowns Separation from Mainstream Society

Despite varying conditions and characteristics, there are striking similarities in the way Chinese shantytown communities developed within the four categories identified. The process involved different factors to those that affected the rise of slum areas in other countries. The study of social mobility explores dynamic trends in social stratification according to changes in social status. There are two important indices in the analysis of social mobility. The first is the rate of upward mobility. The rate of structural mobility depends on differences in class distribution caused by changes in industrial conditions. Such mobility is not a matter of personal choice but a ‘passive mobility’. It is something that happens to people without their involvement or consent. Secondly, there is a ‘circular mobility’ rate, social mobility achieved through self-effort such as education and career advancement.

In 1992, Deng Xiaoping’s South Inspection Speech brought China into a new round of political and economic reforms, leading to a period of rapid economic development. In 1993, the Third Plenary Session of the 14th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China decided to adopt the market economy system. Reforms of state-owned enterprises went beyond the adjustment of management structures. It extended deeply into the revision of property rights and joint-stock system reforms entered the mainstream. Many state-owned industrial, mining, forestry, reclamation and agricultural enterprises went bankrupt through industrial depression, serious operational losses and a failure to adopt market mechanisms. The result was a continuous deterioration of living conditions in shantytowns through industrial and systemic failure. Shantytown dwellers were left behind as rapid industrial and economic development took place across mainstream urban society. People living in these areas were excluded from the process of modernisation and urbanisation and lost the capacity to join the mainstream trajectory of Chinese urban life.

3.1 Industrial and Mining Shantytowns

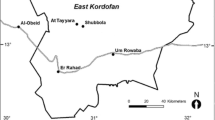

The social status of industrial and mining workers underwent dramatic fluctuations both before and after the renovation of shantytowns. Liaoning Province provided China’s older industrial base. Figure 7.1 shows the location of shantytowns connected with state-owned enterprises within the province. Cities developed around state-run industries such as coal mining, rather than natural population growth on a mercantile model. As coal reserves were exhausted from the 1980s, economic depression and decline followed.

Following the economic reforms from 1993 onwards, former industrial dormitory areas became run-down shantytowns. Control of both the enterprises and their associated worker accommodation transferred to the local government level. Over the course of time, this led to the spread of large areas of self-built and maintained properties. Very unusually, most shantytown residents in Liaoning Province had permanent urban residence certificates, unlike migrants from rural areas. Workers who had once been employed in large collective or state-owned enterprises lost social status during the industrial and economic reforms. An example is the community in Beihou, Fushun City. In 2004, there were more than 1,600 households, including over 400 farming households. The total population was over 4,800, more than 1,200 of the farmers. Over 800 people lived in individual units, more than 1,680 lived in collectively owned units and over 20 in individual households. As can be seen from Table 7.1, the highest proportion of workers—47.5%—lived in the large collectively owned units.

Social mobility for shantytown residents tended to be downward. Mining was the most prestigious occupation in the old industrial base of Liaoning Province, with extensive growth and development in state-run extraction enterprises. There were up to 120,000 workers in Benxi Mining Bureau in 1988. Mining was the core industry in ‘The City of Coal and Iron’. Underground workers enjoyed special privileges such as exclusive access to wine and meat coupons. The mining industry entered recession, reserves were exhausted, there were financial losses in successive years, and mining became the primary focus for industrial reform. The government undertook management buy-outs, and awarded compensation of nearly RMB 10,000 to each miner to enable them to leave the industry and re-enter wider society. The social and economic status of former miners declined rapidly. They went from respected workers in state-owned enterprises to poor shantytown dwellers. Their social and economic status dropped from bourgeois to that of the proletarian poor.

The economic decline led to community collapse. Before the industrial reforms of the 1990s, employers’ logistics department provided services and social security functions. Social relationships in these neighbourhoods reflected the relatively high status and prestige of the workers themselves. There were high levels of social cohesion and order. With economic decline, municipal authorities took responsibility for former work-unit communities. They became defined by geographical location rather than links with particular industries and the support infrastructure these provided. Municipal governments were unable to cope with large-scale industrial reform and community organisations were paralysed by the size and rapidity of these changes.

As a culture of poverty developed, social security systems deteriorated. Unemployment led to serious social security problems across shantytowns. Without steady and reliable sources of income, many residents turned to crime. The older collective system's social cohesion and regulatory frameworks broke down, leading to a rise in anti-social behaviour. In addition, levels of educational attainment in shantytown were comparatively low, mainly only up to primary and junior high school levels. Low educational and cultural aspirations contributed to social problems.

Table 7.2 shows that, Shenyang had an exceptionally high level of residents educated to senior middle school level, some 70%. In the other five cities most people had only attended junior middle school and primary school. A poor educational background restricted the employment opportunities and economic capacity of shantytown residents.

3.2 Slum-Dwellings in Reclamation Areas

China’s state-run farms form a gigantic socio-economic system with four million employees, a population of twelve million and over 47,000 km2 of arable land. It comprises the country’s base for commercial grain production and strategic food reserves. In 1957 in response to a call for the development of mountainous areas, land-reclamation projects were established in Jiangxi Province (see Fig. 7.2). Over 50,000 cadres drawn from Communist Party and government organisations, demobilised troops and educated youths from Shanghai and Yangzhou travelled to the deserted beaches and remote mountains far away from cities and major transport links. Jiangxi Province had a large number of designated reclamation areas. They covered a total area of 16,000 m2, and consisted of reclamation farms, companies, enterprises, schools and managed villages, with some 163 independent accounting units. The location of these reclamation areas and the slums that developed around them can be seen in Fig. 7.2. By the end of 2016, the total population in the Province’s state-owned reclamation areas was 1.3 million in some 383,000 households.Footnote 6 The population was divided into four categories: land-reclamation workers, their families, non-manual workers, and villagers in settlements attached to land-reclamation farms.

With China’s economic reforms, industrial, commercial, architectural and service enterprises developed rapidly, with their total output value exceeding agriculture. Many former farm workers subsequently found employment in other industries. There has been a gradual decline in state-run agricultural and land-reclamation schemes since the 1990s, as their economic planning and operational management systems proved inflexible. Financial debts and the adverse social impact were felt heavily across this sector. By 2009, the asset-liability ratio reached 119%. There was low social security provision for workers and heavy burden on the state-run farms.

In 1994, state-owned farms reversed their policy of arranging employment for the children of employees. In November 2010, Jiangxi Province issued Instruction on Promoting Reform of State-owned Land-reclamation Enterprises in the Whole Province. The reforms involved job realignment, historic debt repayments, outsourcing social services, and more flexible ways of operating. An early retirement policy was introduced for those staff due to retire within five years. The farms disbursed living expenses and paid staff endowment and medical insurance every month until retirement. For those due to retire after five years, compensation payments were arranged based on their length of service. Their endowment and medical insurance were paid under the ‘One Compensation and Two Insurances’ scheme. Some agricultural workers returned to work the arable land as individual tenant farmers or labourers rather than state employees. Most chose to work in cities, while a few remained in farms as contractors and farm labourers. At present, there are a total of 317,000 employees in Jiangxi land-reclamation schemes, including those formerly employed under the old system. The total is made up of 100,000 primary-industry employees, 109,000 secondary and tertiary-industry employees and 108,000 retired workers.

There are three main causes for the gradual deterioration of housing stock within the state-run reclamation schemes. During the 1950s, the ‘Great Leap Forward’ period, priority was always placed on production, with quality of life a lesser concern. Farm workers and their families mainly lived in ‘army barracks’ and ‘tube-shaped apartments’ initially built with coal cinders, mud bricks and timber. Settlements were scattered in remote mountain areas with primitive facilities for water, electricity, gas and other services. Secondly, by the mid to late 1990s, the agricultural economy within these schemes began to decline. With lower financial resources, older houses fell into disrepair. Thirdly, the remote mountain and lake locations with infrequent transport and poor medical, health, cultural and education conditions, restricted opportunities to improve living accommodation. With no development of commercial, residential houses, living conditions lagged behind those of the surrounding villages.

3.3 Shantytowns in State-Owned Forestry Areas

Heilongjiang Forest Industry Group (HFIG) is one of the four big forestry organisations in China. It comprises four forest warden authorities and 40 forestry divisions. HFIG specialises in large-scale afforestation and forestry operation and management, and at the height of its output, its timber yield accounted for 33.5% of the national supply. It has produced a total of 519 million cubic metres of timber, accounting for 21% of the overall national output. HFIG has established social housing projects in small towns dotted across secluded areas of original virgin forest, see Fig. 7.3. These towns are designed to be ecologically sustainable and have advanced industrial and social systems.

Founder Forestry Bureau was founded in 1958 and was the first to reform shantytowns in forestry areas. It closely combined both physical and social regeneration, providing a blueprint for subsequent schemes nationwide. Heilongjiang Founder State-owned Key Forest-area Management Committee was founded in 2015. By the end of 2018, these forested areas had a total population of 59,298 across 25,476 households. There were 4,428 workers on the payroll, including 2,682 employed forestry operatives. Forestry areas were divided into two main categories: working and living space in the mountains and residential areas on the plains. There are ten mountain forest farms and Gaoleng Bureau comprises 22 departments, including public security and justice, culture, education and health, a tax bureau, water-power-heat supply and property management. The sub-district office was established in 1959, and sub-district cadres were all regular staff of the Forestry Bureau. The sub-district consisted of five communities and six neighbourhood committees, and its main mission was to organise workers’ families to contribute to food production and alleviate the shortage of vegetables and cereals. Forestry areas were supplied with economic, administrative, and social management services and were remarkable for self-management, autonomy, and community cohesion.

Before 1970 all forestry workers constructed their houses independently. The Forestry Bureau provided land, timber and other construction materials. Houses were mainly simple and crude with walls made of straw mixed with yellow mud held together by panels. From the 1970s, the Forestry Bureau began to supply brick-and-tile bungalows for the workers. The living area was generally 25 m2 for each household comprising two generations; and 30–35 m2 per household of three generations. As the population increased, people built new thatched extensions both in front and behind the main house and these soon deteriorated and many of the housing schemes became slums.

In 1984, the forestry authorities implemented housing ownership reform, and some staff purchased their public housing. In 1998, the Founder Forestry Bureau issued a one-off voluntary severance payment and some 4,000 employees accepted compensation and withdrew their membership. The economic status of forestry workers remained consistent with fiscal and industrial trends until the 1990s, when forested areas entered recession. There were two main factors, a lack of sustainable resources and an economic crisis brought on by excessive logging and over reliance on the single ‘wood economy.’ Profits declined, and incomes dropped below the national mean level. Following redundancy, many younger or active workers sought work elsewhere. In October 2000, the government launched the Natural Forest Protection Project. Key state-owned forestry areas reduced their timber yield greatly, and commercial logging of natural forests stopped completely in 2014. Safe-guarding China’s ecological security has become the priority. With a shift from plantation operations to forestry management and protection, the demand for employment was greatly reduced. The Founder Forestry Bureau relocated 3,000 surplus staff, and the number of registered employers reduced to 4,428, only 2,682 of them actively in service.Footnote 7 The income of these service staff grew slowly. In 2005, the Forestry Bureau implemented the second housing reform, whereby all publicly owned dwellings were sold to individual staff. Housing ownership and the relocation of workers were important factors in the formation of forestry shantytowns. The Forestry Bureau’s main source of income comes from national investment in the Natural Forest Protection Project. Consequently, the Bureau was no longer responsible for repairing public housing. The ability of workers to fund repairs weakened through unemployment, and housing settlements gradually deteriorated to become dilapidated shantytowns. Nevertheless, even before the sustained regeneration of shantytowns began, some former forestry employees were able to raise money to improve their living conditions. Those who increased their income from running their own enterprises took the lead to improve building standards and conditions. By the time of the formal launch of regeneration projects, the remaining residents faced economic hardship.

3.4 Urban Shantytowns: Examples from Beiliang, Baotou City

Beiliang is the common name for the Northern Plateau in the Donghe District of Inner Mongolia (see Fig. 7.4). The heritage of Baotou is rooted in Donghe with its cultural ‘heart and soul’ drawn from Beiliang. These locations are shown on Fig. 7.4. As the birthplace of ‘Zouxikou Culture’ from the late Qing Dynasty to the formation of the Republic of China, many Han people in Shanxi-Shaanxi area migrated to Baotou. The most famous of these were the mercantile and financier Qiao’s Family, who settled in Baotou during the reign of Emperor Qianlong to open up trade and access to Fushenggong from Qi County, Shanxi. They laid the foundation for the policy of ‘Fusheng First, Then Baotou’. Beiliang enjoyed a prosperous trade in furs and feathers, tobacco, tea and other enterprises, and formed ‘Nine Business Industries and Sixteen Handcraft Industries.’ The area became an important centre for commerce and trade in the Northwest by shipping goods along the Yellow River. For this reason, older, traditional dwellings in Beiliang combined both residential and commercial or workshop accommodation. They typify the characteristic traditional vernacular building style of old Baotou, and have extremely high cultural value.

In 1953, the state established large-scale steel enterprises drawing on mineral resources in Bayan Obo. The development of Baogang was identified as a national key project of the ‘First Five-year’ plan, and Baotou entered the era of heavy industrialisation as ‘Grassland Steel City.’ After Baogang became established, Baotou New City moved westward to Kundulun District and Qingshan District. Baotou Municipal Government moved out of Donghe District, along with all the employees involved in larger enterprises. Those left in Beiliang were employed in small and medium-sized enterprises supporting Baogang. Many settlements in Beiliang degenerated into shantytowns following the development of a market economy in the 1980s. Due to technical weakness and low market awareness, the local enterprises gradually lost competitiveness. During the economic reforms across regional state-owned enterprises in the 1990s, the previously prosperous Bayantala Street in Donghe District declined and many residents were unemployed or faced redundancy. The Beiliang area had a weak municipal infrastructure, with no heating, sewer pipe network and gas facilities or even fire-fighting services. Old and dilapidated earth and timber dwellings accounted for above 90% of the housing stock. Living conditions were primitive. The impact of the severe earthquake that hit Baotou in 1996—at 5.3 on the Richter Scale—reduced already run-down areas to the largest urban shantytowns in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

Beiliang shantytowns covered 13 km2, with a population of 124,000 across 47,000 households. The residents mainly comprised people living on minimum incomes, retirees and vulnerable groups. The reforms of state or collectively owned enterprises in the 1990s resulted in high unemployment and an influx of poorer residents. Over 70% of the population in shantytowns had no regular income. The number of registered unemployed in Donghe District rose to 11,800, 70% of them living in Beiliang. Those on minimum income accounted for 18% of the city’s population. Within Donghe District, there were 30,100 people living at minimum income levels, accounting for nearly 50% of the population, with over 40% centred around Beiliang (Baoshan et al. 2015, 38). The population was also ageing; most young people left the region to find work, increasing the proportion of elderly people and retirees. Beiliang took on the characteristics of a migrant city, home to some seven minorities, including Mongol, Hui and Man. Alongside ethnic diversity came cultural and religious diversity. Five major religions co-existed, Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Catholicism and other forms of Christianity. The renovation of shantytowns had a direct impact on the stability of religious and ethnic relations.

4 Shantytown Renovation and the Remodelling of Communities

Strong central policies, inclusive local strategies and practice, have both consolidated China’s ability to implement the large-scale regeneration of shantytowns, making it become new forms of more integrated mainstream urban settlements. Government policies that emphasised joint ‘central/local’ action and local interventions, were the fundamental means to assure effective control of the regeneration process. More specifically, the policies replaced existing social and planning mechanisms with new forms of a community organisation that enabled residents to adapt to the market economy and establish new economic and social life forms. There were dramatic changes in community organisation, culture and governance. These changes were driven by requirements at both government and community level. Firstly, the state needed to reconstruct a community organisation to assist the government in providing social security and public services. Secondly, the residents of newly renovated shantytowns required a community platform to support economic and social life into the future. The high degree of overlap between ‘official’ and ‘private’ requirements in the public realm became a feature unique to the newly renovated shantytowns.

4.1 Shantytown Development of Community Organisations: Liaoning

Renovation of the living environment

Residents lived in apartment buildings following the regeneration of shantytown areas. The living environment was integrated with surrounding communities living in privately rented flats. The first of the major regeneration projects, the Modi Community in Fushun City, serves as a good example. By the end of 2009, after five years of construction, a total 106 apartment blocks replaced the original shanty dwellings, comprising a population of 16,300 people in 6,400 households. After renovation, the average housing area per household reached 53.8 m2, with a per capita living space of 18 m2. There were major environmental improvements. The introduction of central heating reduced emissions. Asphalt roads now extended to the entrances of housing settlements. Improved lighting and other infrastructure projects enhanced the environmental quality and two public squares became the focus for cultural and leisure activities.

The regeneration of community

The emergence of regenerated community structures is the highlight of shantytown renovation in Liaoning. The Civil Affairs Department formulated a community reconstruction plan before the physical works took place, based on a core working platform of community’s Party organisations. This was an innovative way organising public services in China at that time. Alongside the community’s Party Committee, it also established Community Neighbourhood Committee, Residents’ Congress and a Community Council. Benxi City established and further developed this community network model involving the alderman, community assistants, residents’ representatives, advocacy organisations, and volunteers to ensure smooth communication and service delivery channels.

These measures established good order and community cohesion. Following the renovation, the new community settlements varied in size from between 3,000 and 10,000 inhabitants across some 1,000 to 3,000 households,Footnote 8 far greater than those in the older ‘unit’ communities. The increase in scale required new measures for security and social management. The residents selected their floors and living areas independently following a fair distribution principle, as the newly formed community came from different shantytowns, and did not know each other. The newly renovated shantytowns were equipped with community police stations and officers according to national standards and security patrols. Crime prevention and emergency management were strengthened, and community security improved significantly.

Public service facilities were also enriched. Health services are one example. As the state-owned enterprises closed, the unemployed lost medical service assurance, and public health levels declined. Following the regeneration projects, each settlement had a community clinic and full-time medical workers. Changes in health service infrastructure have greatly improved the quality of life for the residents. After the move from shanty dwellings to more substantial buildings, the biggest change residents identified was the improvement in the image of their communities. They had become a mainstream urban community with a clean environment and modern facilities.

Increased levels of social mobility became the most significant effect of shantytown renovation. The inhabitants of the newly renovated shantytowns were mainly former employees of large state or collectively owned enterprises who had fallen into poverty during the reforms and the process of industrialisation and urbanisation. The regeneration of shantytowns supported redundant miners, reversed the decline in social status and brought them back into modern urban society.

4.2 Housing Regeneration and Community Reconstruction in Jiangxi

Shantytown renovation combines with new urbanisation

The renovation of housing stock in Jiangxi Province started in 2011, the first time any remedial work had taken place since the construction of large-scale barrack style accommodation in the 1950s. It began with the construction of 331,000 social affordable housing, including the renovation of 60,000 substandard dwellings in reclamation areas.Footnote 9 The project covered 157 land-reclamation units and involved 71 administrative districts in across the whole province.Footnote 10

The project focused on the renovation of run-down households within the managerial district of the reclamation areas, and gave priority to supporting the most vulnerable families, or those on the lowest levels of social security. To be eligible for renovation, houses had to be either:

-

over 40 years old with signs of serious deterioration;

-

constructed from mud and thatch;

-

identified by the provincial construction department;

-

deemed unsafe due to unqualified gas supply, lack of fire-fighting and other facilities, and pose serious potential safety hazards;

-

or part of residential areas where more than 50% of the housing stock was centrally owned or in disrepair.

The regeneration of these properties in Jiangxi was typical of similar renovation projects in state-owned housing across China. The project placed urban regeneration as an important part of a new approach to urbanisation. The basic philosophy was to group population density into open areas, localise industry onto industrial parks, and to modernise agriculture. A new tripartite pattern of community developed comprising modern open ‘parkland’ for residential and industrial areas, tourist attractions and new forms of urbanisation. By adopting this approach, people could be accommodated more strategically and new patterns of urbanisation encouraged. It combined urban regeneration with the construction of market towns with surrounding villages within easy reach. The larger villages were within 3 km of each market town with smaller hamlets only another 3 km further from the central market hub. The demolition process ensured that the inhabitants were moved closer to key tourist attractions, agricultural and industrial districts and industrial parks. There were 1.1 million people living in land-reclamation projects across Jiangxi Province, and through the urban regeneration project, a quarter of a million moved to the open countryside, some 30% of the total population. There was a total of 155 small towns in land-reclamation areas across Jiangxi, and the total urban area exceeded 450 km2. There is a large-scale urban population at 690,000, 62.1% of which live in towns, which is a proportion about 11% higher than the mean value of the whole province (Xinhua News Agency Jiangxi Branch 2013, 173).Footnote 11

By 2016, over a quarter of a million run-down properties were renovated and newly built houses covering an area of over 17 km2. Nearly 17 km2 of dilapidated housing had been cleared and over three quarters of a million people rehoused. The older barracks and adobe houses were all replaced with brick and concrete structures. In the Yunshan Group, for example, per capita, living space more than doubled from 20m2 to 45m2. In residential districts, improvements in piped drinking water introduced centralised sewage systems, clean energy and brought living standards to the same level as urban areas. With the improvement of employment, education and hospital conditions, peasant farming went from low-income physical labour to a respected and dignified career.

Rustic market town communities

As the predominant economic activity within the reclamation areas was farming, living standards and accommodation inevitably took on a primitive, rustic character. A key aim of the regeneration projects was to reinvigorate and revive rural life, respecting the rustic character but introducing modern facilities and infrastructure. An example can be given from Jiangxi Yunshan Group’s Fruit Forest Company. Displaced communities were resettled in new accommodation in Dayuan Village managed by Yongxiu County. Residential workers within the Yunshan Group’ were completely integrated with local villagers, and a community centre provided a shared leisure square with fitness equipment, basketball court, outdoor stage and a rural history museum. Following the agricultural reforms of the 1990s, most workers, except for a few in managerial posts, no longer relied on farms for employment, and travelled away to find work alongside local farmers. They would leave the elderly and children behind and return home only during holidays and festivals. Unlike the local farmers, the agricultural labourers came from other parts of China away from their native home towns. The newly renovated housing settlements were often not their only place of residence and internal migration gave the children of farm workers more employment choices.

4.3 Forest-Area Shantytown Renovation

Forest-area shantytown renovation

Heilongjiang Forest Industry Group and Founder Forestry Bureau were the first forestry areas to renovate shantytowns within their jurisdiction. The first phase of renovation ran from 2009 to 2011, with 900 new houses built. The second lasted from 2011 to 2015, with a total of four thousand new houses completed. Before 2012, these projects drew on supporting funds from provincial government. Later, there was a subsidy of RMB 300 per m2 from the state alongside funds raised within the enterprises themselves.Footnote 12 The third phase ran from 2015 to 2017, and except for funds released from the national budget, it completely relied on policy loans from state-run banks, and the annual interest burden was heavy.Footnote 13

Founder Forest Bureau received a total investment of RMB 1.13bn and renovated some 21,600 shantytowns, including, 10,762 newly built settlements within the areas under its jurisdiction. Some 464 settlements were established or refurbished within forestry plantations and this encouraged workers deep in the upland areas to migrate to settlements on lower ground. The result was the urbanisation of forest society as businesses and urban development spread to forestry areas. Maintenance and renovation projects involved mainly old, unfit or dangerous houses in plantation dormitories. A total of 10,390 units were refurbished with replacement windows, external-wall insulation and roof tile reinforcement.

Community development in forestry shantytowns

In 2005, against the background of a nationwide move to promote the construction of new urban communities, the forestry Neighbourhood Committee finished the process of community transformation. Community structures developed as the regeneration projects progressed, and the number of Neighbourhood Committees increased from six to ten. Each community had office space of around 500 m2, with a multi-purpose community service hall, charity supermarket, daycare room, the school for the children of residents, etc. The range of public services increased. Previously, these community services had been restricted to the most basic needs such as local Communist Party construction, family planning, civil affairs and re-employment training. A standard service system developed during the shantytown renovation process, drawing on the experience gained from projects in Ang'angxi District and Qiqihar City. The main difference between community organisations in forestry areas and those in cities was that the former had a vertical management structure. All 70 cadres for the sub-districts and five communities were employed by the Forestry Bureau, and under its direct management.

Newly renovated settlements in forestry areas were organised and managed individually rather than collectively. Each unitary settlement could make decisions on investment, development, and management, making full use of the renovation project and applying planning standards set by Harbin's provincial capital. This led to a high standard of construction across junior and senior middle schools and Forestry Bureau Hospitals in newly developed areas. Not only did the standard of facilities and equipment exceed that of surrounding cities and counties, but the winter heating service extended a month beyond that of adjacent areas. Distinct communities began to emerge with a shared destiny.

4.4 Shantytown Regeneration in Urban Areas

Physical renovation of urban shantytowns

In February 2013, the authorities in Beiliang began the process of acquiring, relocating and refurbishing shantytowns and temporary settlements across the region. The process involved three compulsory acquisition and relocation campaigns, known as the ‘100-day Problem Solving’, the ‘Spring Battle’ and ‘Autumn Battle.’ By October 2014, a total of 124,000 people across 47,000 households were rehoused in new properties or had their homes redeveloped. The total living space involved amounted to 4 km2 houses within an area of 13 km2. Two methods were adopted to manage the relocation of shantytown dwellers. The first combined monetary compensation with property-rights exchange, and some 14,000 residents from the 47,000 households received monetary payments. Another 15,000 were relocated through buy-back of commercial residential houses, with a monetary repayment rate of 61.7%.Footnote 14 The second measure combined relocation away from the shantytown areas, supplemented by in-situ renovation. To respect the customs of the predominantly Muslim Hui people’s in living close to places of worship and their taboos against the removal of tombs, relocation areas were chosen around the Grand Mosque.Footnote 15

By the end of 2015, 33,000 new or buy-back refurbished houses were completed and delivered, the relocated residents were all in place. The per capita living space for former inhabitants of Beiliang shantytowns more than doubled from 12 m2 to 26 m2. Among the 45,000 replacement houses were 20,000 self-owned dwellings with property rights. The area of these homes ranged from 75 m2 to 90 m2. A total of 25,000 economically affordable houses were provided with an area of between 50 m2 and 65 m2 as well as and lower-rent houses for those on low-incomes.Footnote 16

Community development in urban shantytowns

Drawing on experience from previous renovation projects, Baotou City planned to establish a relocation area of some 4.78 km2 near the city centre, in order to engage the interest of those moved from the shantytowns. Two large areas of newly built houses were built to the north and south of the catchment area consisting of five communes and 15 residential communities. Altogether, some 33,000 replacement houses were constructed. Each of the new communities comprised around 6,000 households with a population of between 3,000 and 10,000, far greater than that of other schemes. Each settlement was simultaneously equipped with six primary and secondary schools, eight pre-school nurseries, nine community service centres, two community health service centres and a large park square. The new living space environment aimed to satisfy the requirements of young people to in order to retain a population balance and ensure the longer sustainability of the communities.

Whereas the regeneration process in Beiliang prioritised people’s economic livelihood, the schemes in Baotou City encouraged the improvement of basic public services. The endowment insurance rate increased from 79% to 91.3%, and the medical insurance rate increased from 82 to 100%, achieving full coverage of the population. The schemes actively encouraged growth in public-welfare employment. When the programme was first launched in early 2013, the number of unemployed in Beiliang town stood at around 10,000, with another 8,000 added as the shantytowns were dismantled. By providing employment in property management, cleaning, ecological projects and social security roles, supporting vocational training schemes, total 9,277 people were redeployed with minimum salaries coming into line with the city’s ‘mainstream’ population.Footnote 17

5 Social Characteristics of Newly Renovated Shantytowns

The shantytown renovation projects, which started in 2005, will come to an end in 2020. What historical and theoretical perspectives and lessons can we apply from the process? In the first instance, the regeneration projects involved physical improvements, but this led to a deeper community and social development level. The process has completely transformed the living conditions of poorer urban communities. It brought lower-income residents living at the bottom of urban society back into China’s urbanisation process and achieved a balance between urban regeneration and social harmony.

By prioritising social and physical development, the Chinese experience can contribute to urban regeneration practice worldwide. These projects achieved a balance between centralised initiatives and local autonomy by re-constructing the social and community structures. They deployed a range of agencies from centralised authorities through local governments and the residents themselves. Together, they have completed the heavy tasks of shantytown reconstruction and the relocation of their inhabitants. New forms of settlement are becoming the most important platform for lower-income residents from the former shantytowns. This has helped them to achieve a higher residential status and reconstructed their economic and social life. Residual traces of shantytowns are gradually phased away as these new settlements integrate into modern urban life.

These new forms of urban community are of deep social significance, and provide strong and valuable lessons for urban regeneration practice worldwide.

5.1 Urban Regeneration as an Agent for Social Mobility

China’s shantytowns arose as the result of industrial and decline and the passing of older forms of state-controlled and collective systems of organisation. As China’s economy developed rapidly, shantytowns were left behind in the process of industrialisation and urbanisation. Before the economic reforms of the early 1990s, employees of state-run enterprises lived in industrial dormitories and enjoyed medium economic social status. As the planned economic system failed to keep pace with the rapid development of the market economy, their status declined, and their dormitory areas deteriorated.

The renovation of former shantytowns has transformed the image of these communities reduced the gap in living standards and layers of social division within urban areas. It has brought poorer populations back into mainstream urban society by a powerful policy of social redistribution. As a people-centred project, these programmes rebalanced the expectations and living standards of previously disenfranchised communities. As a form of ‘Urban Development’ practice, China’s urban regeneration programmes demonstrate a particular ‘socialist’ approach to the reconstitution of urban space. It is clearly a very different approach to the process of slum-clearance and ‘gentrification’ in both Western contexts and the somewhat scattered and piece-meal regeneration practices encountered in Latin American countries.

5.2 Reconfigured Living Space for Lower-Income Urban Dwellers

In the early phases of shantytown renovation, the focus was very much on enabling people to fully enjoy the fruits of China’s economic and social reforms. After 2008, the emphasis broadened to encompass a response to the global financial crisis. As well as tackling issues of social mobility and equality, the regeneration programmes provided a mechanism to boost consumption, expand investment and invigorate the management of land resources. With the introduction of the ‘three one-hundred-billion people’ policy in 2014, the mission was expanded again, and the regeneration programmes became a vehicle for new forms of urbanisation and environmental management. As a ‘development project’ these schemes sought to achieve a more harmonious relationship between humanity and the environment, balance the needs of the economy and society, and improve urban quality.

From the perspective of urban sociology, the distinctiveness of the Chinese experience lay in this multi-functional and multi-dimensional approach to driving economic development. In this important respect, it differed from Western forms of urban regeneration and gentrification, in that the shantytown residents were always the largest beneficiaries. The projects were inclusive and people-centred and did not create artificial separations between economic and social benefits nor create distinctions between the affected groups.

The success of China’s shantytown renovation demonstrated the possibility of improving the physical environment and integrating former residents into contemporary urban life. The biggest challenge facing the newly renovated or relocated settlements was how to transcend purely physical regeneration and achieve systematic and permanent reforms in community life.

5.3 Shantytown Regeneration as a Two-Way Process

The Chinese government always played a central co-ordinating role in the redevelopment of shantytowns. While local authorities prepared and implemented the programmes, the strategic steer came from national government policy. In 2009 the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development issued Instructions on Promoting Urban and State-owned Industrial and Mining Shantytown Renovation. This emphasised the need for strong public policy and welfare programmes alongside the physical refurbishment and placed organisation and guidance, funding and support firmly in the hands of government agencies. The redevelopment schemes resolved the housing problems of lower-income groups. Improving the quality of life and environment, enhanced the public perception of the Chinese Communist Party and central government. The programmes involved local people and empowered them to participate in developing solutions and creating greater social cohesion.Footnote 18

The process of ‘community transmission’ involved the government in a co-ordination role that proved key to the success of the regeneration programmes. The government’s initiative proved to be the major driver and was the decisive factor in the reconstruction process. Community structures and organisations provided synergies by conveying residents’ social security and other requirements to central government through advocacy networks. The particular features of shantytown community organisation meant that human and financial resources’ commitment was greater than those that applied to mainstream communities. For example, Liaoning Province’s newly renovated shantytowns received an injection of human and material resources for community governance, improved social services and facilities. These resources became the key mechanism for improving the quality of life for the local community. Within Beiliang New District, Baotou City has established mechanisms for community development under the direct management of district government at all levels. These systems comprise interdependent networks with the local Communist Party Committee as the central hub, service delivery organisations responsible for implementation and neighbourhood committees sharing responsibility for governance. With social groups fully participating in the process, this forms a symbiotic ‘circle’ to coordinate and deliver community services.

5.4 Community Infrastructure and Improved Services

The improvement of housing conditions and living environment was the first step in the regeneration process. Once residents moved into the newly built or refurbished properties, the next step was to ‘de-shanty town’ the emerging communities. The key challenge was to reduce the gap between the lower quality of life previously experienced by shantytown dwellers and the wider, strategic goal of integrating them into contemporary urban economic society.

The refurbishment and redevelopment schemes contributed to rising social mobility. Those who embraced the changes enthusiastically were faced with the fresh challenge of adapting to new urban and community life forms. Unlike their neighbours, residents of the newly redeveloped communities were originally employed in collective or state-owned enterprises. Consequently, they tended to have a single vocational skill and less capacity for re-employment in other industries. They lacked the social resources to cope with market competition. Most workers from heavy industrial or mining operations held lower-skilled, non-technical roles. Those from agricultural or forestry backgrounds worked in lower-skilled or semi-technical roles and consequently lacked employment prospects in other sectors. Workers living in urban shantytowns tended to be mostly self-employed or freelancers and so were in a comparatively strong position to adapt to the new market economy. Our field surveys found that the increasing age of industrial and mining workers in the newly redeveloped areas further increased their difficulties in finding alternative employment. The educational background of younger residents was improved, but they tended to move away, resulting in a predominantly ageing community with associated problems.

All these factors meant that former shantytown residents relied heavily on social and administrative services and mutual support networks within their community. Community structures and organisations assumed a far greater importance within the new or refurbished settlements than in other residential areas. A wider and more complex support network was required to manage the transition to new and improved living accommodation and meet the social, economic and cultural challenges of building new communities. These new communities had particular challenges and were a ‘special case’ in wider urban development. Their integration into contemporary urban life was the key challenge to overcome as China entered a new era of urbanisation.

6 Comparative Analysis of Community Reconstruction Projects

A common feature across China’s newly renovated shantytowns was the lack of access to economic and social resources. Most residents were self-employed having lost employment in state-owned enterprises. Their only option was to reconstruct their economic and social position in order to enter mainstream urban society by using what resources were available to them within their communities. Community development and capacity-building was an urgent need.

The future of these communities depended on a process of reconstruction and transformation. The historical legacy of older collective and communist collective systems forged uniquely distinctive communities. The erosion of these systems during China’s economic reforms affected the ability of these communities to organise and support themselves. It could be argued that the capacity for community development within the four categories of shantytowns described in this study varied with the extent of decay within their original social structures. The level of social deterioration determined the extent to which these communities were able to reconstruct themselves.

The most dynamic forms of community reconstruction occurred within urban shantytowns such as those around Beiliang, Baotou City. In this instance, regional state-owned and collective enterprises had become bankrupt during early economic reforms in the 1980s. Residents abandoned the thought patterns and behavioural models associated with a planned economic system, and adapted to the new market conditions. With no other sources of enterprise support, intervention from the urban government was substantial. Through a meticulously planned market and living environment, these communities have retained their young people and achieved a more balanced age profile.

In the case of settlements in agricultural and forestry areas, once the commercial and administrative functions were separated through the system reforms, state-owned enterprises survived as managers and custodians of state assets. They retained sufficient economic resources to support employment initiatives and entrepreneurship. The special co-operative relationship between state-owned enterprises, local government and the newly renovated shantytowns created favourable conditions for subsequent development.

Within state-run industrial and mining communities such as those in Liaoning Province, the picture was very different. The depletion of natural resources and the effects of systemic reform led to the complete disintegration of the original state-owned enterprises. Lacking other forms of support, the former mining and heavy industrial areas became the exclusive focus of efforts to renew and reinvigorate any semblance of community cohesion. The reform process began relatively early in Liaoning Province, with the result that many former shantytown residents were ageing and less economically active. Economic decline across local cities had weakened their capacity to support community reconstruction, and urban inclusion faced difficulties.

6.1 Mechanisms to Build the Capacity for Self-Development Across Urban Shantytowns

As already noted, the former shantytown areas around Beiliang had the strongest capacity for self-development. Their ability to reconstruct their social structures and community cohesion relied predominantly on the strong role of national urban integration initiatives (Dan 2018). To strengthen community services’ capacity, Baotou City implemented a model of direct district management in Beiliang New District. The existing three tiers of management—‘District/Sub-district/Local Community’ were replaced with a flatter and more direct ‘District/Community’ structure. Donghe District Government engaged with each community directly, in order to facilitate detailed community management, and respond to problems more quickly. National integration systems could effectively mobilise and direct cooperation between the main agencies within society. Premier Li Keqiang twice inspected the Beiliang communities and took a direct, personal involvement in the regeneration projects. He promoted the transition from communities that were simply surviving—‘worrying about living’—to communities that were ‘liveable and viable’, such intervention laid a solid foundation for subsequent self-development within these communities. Beiliang’s regeneration schemes received full support from China Development Bank, large-scale enterprises, social organisations and other agencies in financing, project development and social services. Tsinghua University and the China Urban Planning and Design Institute formulated a detailed regulatory plan of Beiliang’s clearance areas. This ensured that residents had access to the same educational, medical, environmental and cultural, public services or information resources as other residents across the whole city. Indeed, the level of facilities available began to exceed that of surrounding cities, and the social stigma associated with lower-income shantytown settlements was eliminated.

Forms of community self-governance emerged from the regeneration process. North 1st Community, the first to be directly managed by the government of Donghe District, is one example. It fully implemented Communist Party policy,Footnote 19 with over 15 full-time staff, plus public-welfare posts for college students and volunteers, a total of over 30 workers in all. They operated from a centre which occupied some 2,300 m2, which provided a ‘one-stop’ hub for 29 integrated services, including localised Communist Party branches, sub-district and civil affairs, social security and family planning, Every 300 households within the community were organised into a network of individual units, each with their own manager and sub-tiers within each residential block, forming three-levels of management. Beiliang New District had 28 social organisations, 38 co-constructed organisations, six residential voluntary organisations and five groups. These groups included meetings of residents’ representatives, a consultation committee and owners’ committee, and enterprises governed by the residential units, all of which worked together to build and develop the community. The settlements established and promoted their own community organisations to meet grass-roots requirements.

Finally, systems were established to empower communities to organise themselves. The focus was on raising awareness of working in partnership, capacity-building and helping communities adapt to the changes in their society. Beiliang’s ‘Zouxikou’ culture provided the model for these self-support mechanisms, an approach that developed as modern Shanxi and Shaanxi Han peoples conducted business in Baotou. It combined a strong sense of self-determination, endurance and the ability to negotiate and seek consensus or compromise with teamwork, a sense of neighbourly responsibility mutual assistance. Local cultural attributes of this kind were embodied and exemplified in the process of shantytown clearance. The regeneration schemes drew on the inherent sense of self-determination that characterises the culture of Beiliang, so that community spirit developed organically. The tradition of local community festivals continued, and extended the ability to forge and deepen personal relationships. With the new residential blocks as the core unit, the new settlements drew on traditional social roles such as ‘Peacemaker’ and ‘Old Uncle’ to mediate in neighbourhood disputes, and implemented forms of participatory community governance.

6.2 Sustainable Development in State-Owned Agricultural and Forestry Areas

Within the former state-run industrial and mining areas, the Government had no option but to intervene directly to reconstruct community organisations and provide social security services. In these areas, state-run enterprises survived the reforms, and provided the backbone structure and framework for later regeneration programmes. Newly renovated communities strove to establish alternative industries within the forestry areas alongside innovative forms of forest management. With the introduction of the Natural Forest Protection Project in 2000, ecological services provided by international management and protection agencies replaced timber production. Drawing on the rich natural and landscape resources of forested areas, tourism, conservation, the planting of indigenous species and forestry maintenance became the main alternative industries.

Forestry areas also had an intrinsic advantage when it came to promoting community cohesion. Forestry communities had developed around common goals and a sense of a shared future and so were willing to invest capital in local education training, medical health and house building. The emphasis on improving the welfare of employees meant that the level of public services was generally higher than those of surrounding counties. Forestry societies were built on strong personal relationships. Community cadres and service provision were run by Forestry Bureau staff and the combination of close geographical and working relationships ensured effective communication and the development of appropriate and carefully planned and targeted services. The state-run Forest Management Co., Ltd. managed substantial forestry resources, and became a regional hub for commerce, health, culture, education, retail and employment.

Two outstanding issues remain to be resolved in future redevelopment within state-run agricultural areas. Firstly, occupation levels within the renovated settlements remain low, due to the mobility of the workforce. Many residents travelled away to find work with children and the elderly forming the core of the community. There are still issues with low levels of supporting infrastructure, which cannot satisfy water, electricity, waste disposal and other requirements. Failures in water and power supply, and infrequent waste disposal, remain common problems. Furthermore, residents of the new communities were unaccustomed to the bill payment system of collective dwellings, and at present, recently refurbished dwellings rely heavily on maintenance carried out by small enterprises for the agricultural or forestry workforce.

The communities’ own self-support system proved equally important as the Government’s urban integration and management systems. The ability of these new settlements to support themselves depended on the capacity of each individual community. The strengthening and building of capacity for community governance and participation will both reduce the expense of property management and the ability of public services to meet basic living requirements.

6.3 Ageing Populations in State-Run Industrial and Mining Settlements

In 2005, Liaoning Province took the lead in the regeneration of shantytowns in state-owned industrial and mining areas, a process which has lasted 14 years. Before the first of the major co-ordinated schemes, the responsibility for shantytown renovation lay with local authorities. Time scales were tight since the houses had to be demolished, constructed and occupied within the current single fiscal year. Construction quality was low, often leading to subsequent maintenance and management problems. The biggest problem was low expenditure on maintenance, mainly due to the general ageing of the population. Workers made redundant in the 1990s entered old age ten years after the renovation schemes, and employment difficulties increased for those groups with lower skills and weak employment prospects. The continuing gap in living standards between former shantytown residents and other urban communities led many ‘second generation’ shantytowns dwellers to move away. This weakened these communities’ capacity to organise themselves when they still had a long way to go.

There were also problems shantytowns consolidation and sustainability. The level of poverty and lack of capacity meant that state support was still required. To ensure sustainable development into the future, capital support should be ensured by helping local communities establish maintenance funds. Combining central and local financial initiatives should be possible to sustain the operational capacity of these newly renovated settlements.

7 Conclusion

As urbanisation increases and societies become more individualised, people rely less on the public domain, and community cohesion tends to decline. Within China, however, particular factors encourage community reconstruction. Communities provided the essential platform for the transfer of systems and services from state-run enterprises during the economic reforms. With the rise of greater social mobility, the community played an important role in promoting social integration as an intermediate platform connecting the state and the individuals.

It must be emphasised that, following the transformation of the economic system, and the renewal of community structures, the renovation of shantytowns became a major force for community development. As the public domain between Government and individuals, the local community provided common living space and was the nearest approximation to the private domain. The living requirements of residents became the main driver for productivity within these communities. All communities and all societies require geographical links and associations to maintain and improve their quality of life and civilisation. A responsive approach to the needs of individual communities became the main theme and hall-mark of new forms of urban community within China. The community-centred approach of promoting social cohesion by transforming the subordinate status of communities was the outstanding feature of these social regeneration projects. Community needs were the central focus in each case.

We envisage that in future, the redevelopment of these communities will break the cycle of community administration → administrative dependence → insufficient capacity for self-management. Instead, greater levels of empowerment will resolve economic and social development problems at a local level. Communities faced three main challenges in the transition from shantytowns to new forms of urban settlement.

Firstly, they required a balanced population structure to remain sustainable, and scientific planning and regulation were required to achieve this. Baotou began its shantytown renovation eight years after Liaoning Province, and consequently, Beiliang had the advantage of learning from previous experience. There was a high standard of planning with improved living standards as the goal. There were greater public service resources available than in surrounding areas, enabling the schemes to meet the basic living, cultural and educational requirements. This encouraged younger people to stay within the community, avoided rapid ageing and ensured regional vitality. A balanced population structure relied on sound planning and design and also required constant improvements in living standards. The basic conditions to ensure a population balance included better living facilities, a more ‘fashionable’ environment, improved public services and sufficient employment and self-employment.

These newly regenerated settlements should remodel the ‘heart’ of the community at a grass-roots level. The foundation for this transformation involves the vigorous improvement of the employment and entrepreneurial environment, and reconstruction of living standards. Redundant workers urgently need retraining in areas such as tourism, catering, nursing, housekeeping, child-care, and other specialist occupational skills. They required venture capital support to overcome reliance on public-welfare employment and to enhance their employability in the open market. The communities themselves were not an economic entity or source of employment. To secure employment residents had to contact a range of government agencies, universities, scientific research institutions and forestry or agricultural enterprises. They also had to innovate and establish their own enterprises, and explore what local resources were, available.