Abstract

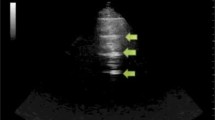

Lung ultrasound is a simple, bedside, non invasive surface imaging technique based on basic signs and simple pattern recognition, applicable almost in any conditions. Despite its simplicity, there is a number of advanced clinical applications which makes it particularly suitable and useful in critically ill patients on the intensive care unit (ICU). In particular the recognition, and analysis of, four fundamental lung ultrasound signs and their change in time, allow the clinician to monitor pulmonary congestion, pulmonary aeration, the haemodynamic state and pneumothorax size at the bedside, especially in these types of critically ill patients. Furthermore, a combination of lung ultrasound with the ultrasonographic study of other organs, mainly heart, vessels and abdomen, allows a more accurate diagnostic assessment in many clinical situations like major trauma, undifferentiated hypotension, cardiac arrest and acute respiratory failure.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Volpicelli G. Lung sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:165–71.

Volpicelli G, Lamorte A, Tullio M, et al. Point-of-care multiorgan ultrasonography for the evaluation of undifferentiated hypotension in the emergency department. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1290–8.

Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:749–57.

Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:577–91.

Lichtenstein DA, Lascols N, Meziere G, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of alveolar consolidation in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:276–81.

Lichtenstein D, Meziere G, Biderman P, et al. The “lung point”: an ultrasound sign specific to pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1434–40.

Volpicelli G. Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:224–32.

Agricola E, Bove T, Oppizzi M, et al. Ultrasound comet-tail images”: a marker of pulmonary edema: a comparative study with wedge pressure and extravascular lung water. Chest. 2005;127:1690–5.

Jambrik Z, Monti S, Coppola V, et al. Usefulness of ultrasound lung comets as a nonradiologic sign of extravascular lung water. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1265–70.

Volpicelli G, Caramello V, Cardinale L, et al. Bedside ultrasound of the lung for the monitoring of acute decompensated heart failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:585–91.

Gargani L. Lung ultrasound: a new tool for the cardiologist. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2011;9:6.

Picano E, Frassi F, Agricola E, et al. Ultrasound lung comets: a clinically useful sign of extravascular lung water. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2006;19:356–63.

Miglioranza MH, Gargani L, Sant’Anna RT, et al. Lung ultrasound for the evaluation of pulmonary congestion in outpatients: a comparison with clinical assessment, natriuretic peptides, and echocardiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:1141–51.

Mallamaci F, Benedetto FA, Tripepi R, et al. Detection of pulmonary congestion by chest ultrasound in dialysis patients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:586–94.

Noble VE, Murray AF, Capp R, et al. Ultrasound assessment for extravascular lung water in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Time Course for Resolution Chest. 2009;135:1433–9.

Soummer A, Perbet S, Brisson H, et al. Ultrasound assessment of lung aeration loss during a successful weaning trial predicts postextubation distress*. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2064–72.

Bouhemad B, Liu ZH, Arbelot C, et al. Ultrasound assessment of antibiotic-induced pulmonary reaeration in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:84–92.

Bouhemad B, Brisson H, Le-Guen M, et al. Bedside ultrasound assessment of positive end-expiratory pressure-induced lung recruitment. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:341–7.

Lichtenstein DA. BLUE-protocol and FALLS-protocol: two applications of lung ultrasound in the critically ill. Chest. 2015;147:1659–70.

Lichtenstein D. Fluid administration limited by lung sonography: the place of lung ultrasound in assessment of acute circulatory failure (the FALLS-protocol). Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6:155–62.

Lichtenstein DA, Meziere GA, Lagoueyte JF, et al. A-lines and B-lines: lung ultrasound as a bedside tool for predicting pulmonary artery occlusion pressure in the critically ill. Chest. 2009;136:1014–20.

Volpicelli G, Skurzak S, Boero E, et al. Lung ultrasound predicts well extravascular lung water but is of limited usefulness in the prediction of wedge pressure. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:320–7.

Picano E, Gargani L, Gheorghiade M. Why, when, and how to assess pulmonary congestion in heart failure: pathophysiological, clinical, and methodological implications. Heart Fail Rev. 2010;15:63–72.

Oveland NP, Lossius HM, Wemmelund K, et al. Using thoracic ultrasonography to accurately assess pneumothorax progression during positive pressure ventilation: a comparison with CT scanning. Chest. 2013;143:415–22.

Volpicelli G, Boero E, Sverzellati N, et al. Semi-quantification of pneumothorax volume by lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1460–7.

Kelly AM, Druda D. Comparison of size classification of primary spontaneous pneumothorax by three international guidelines: a case for international consensus? Respir Med. 2008;102:1830–2.

Galbois A, Ait-Oufella H, Baudel JL, et al. Pleural ultrasound compared with chest radiographic detection of pneumothorax resolution after drainage. Chest. 2010;138:648–55.

Kirkpatrick AW, Rizoli S, Ouellet JF, et al. Occult pneumothoraces in critical care: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial of pleural drainage for mechanically ventilated trauma patients with occult pneumothoraces. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:747–54; discussion 745–754.

Scalea TM, Rodriguez A, Chiu WC, et al. Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST): results from an international consensus conference. J Trauma. 1999;46:466–72.

Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Laupland KB, et al. Hand-held thoracic sonography for detecting post-traumatic pneumothoraces: the extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (EFAST). J Trauma. 2004;57:288–95.

Hosseini M, Ghelichkhani P, Baikpour M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography and radiography in detection of pulmonary contusion; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg (Tehran). 2015;3:127–36.

Soldati G, Testa A, Silva FR, et al. Chest ultrasonography in lung contusion. Chest. 2006;130:533–8.

Hyacinthe AC, Broux C, Francony G, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography in the acute assessment of common thoracic lesions after trauma. Chest. 2012;141:1177–83.

Leblanc D, Bouvet C, Degiovanni F, et al. Early lung ultrasonography predicts the occurrence of acute respiratory distress syndrome in blunt trauma patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1468–74.

Perera P, Mailhot T, Riley D, et al. The RUSH exam: rapid ultrasound in SHock in the evaluation of the critically lll. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:29–56, vii.

Hernandez C, Shuler K, Hannan H, et al. C.A.U.S.E.: cardiac arrest ultra-sound exam--a better approach to managing patients in primary non-arrhythmogenic cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2008;76:198–206.

Volpicelli G. Usefulness of emergency ultrasound in nontraumatic cardiac arrest. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:216–23.

Blaivas M, Fox JC. Outcome in cardiac arrest patients found to have cardiac standstill on the bedside emergency department echocardiogram. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:616–21.

Breitkreutz R, Price S, Steiger HV, et al. Focused echocardiographic evaluation in life support and peri-resuscitation of emergency patients: a prospective trial. Resuscitation. 2010;81:1527–33.

Lichtenstein DA. How can the use of lung ultrasound in cardiac arrest make ultrasound a holistic discipline. The example of the SESAME-protocol. Med Ultrason. 2014;16:252–5.

Lichtenstein DA, Meziere GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008;134:117–25.

Anderson KL, Jenq KY, Fields JM, et al. Diagnosing heart failure among acutely dyspneic patients with cardiac, inferior vena cava, and lung ultrasonography. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1208–14.

Kajimoto K, Madeen K, Nakayama T, et al. Rapid evaluation by lung-cardiac-inferior vena cava (LCI) integrated ultrasound for differentiating heart failure from pulmonary disease as the cause of acute dyspnea in the emergency setting. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:49.

Mantuani D, Frazee BW, Fahimi J, et al. Point-of-care multi-organ ultrasound improves diagnostic accuracy in adults presenting to the emergency department with acute dyspnea. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17:46–53.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Volpicelli, G., Schreiber, A., Boero, E. (2022). Advanced Lung Ultrasound. In: Walden, A., Campbell, A., Miller, A., Wise, M. (eds) Ultrasound in the Critically Ill. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71742-1_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71742-1_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-71740-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-71742-1

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)