Abstract

The main aim of the present chapter is to contribute to an elaboration of central issues and possibilities for developing a training programme to improve collaboration between the criminal justice system (CJS) and mental health services (MHS). A theoretical framework rooted in social innovation (SI) and communities of practice is used to reflect upon the gap between initial plans and real time practice and the learning that took place. Three episodes from the EU funded project named COLAB are presented and analysed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The main intention of the EU funded COLAB project (COLAB-H2020-MSCA-RISE-2016/734,536) was to introduce new ways of collaborating and innovating into the criminal justice system (CJS) context. This would be supported by interprofessional training in the field (Hean et al., 2015a). This need for interprofessional training is supported by The Lancet Commission (Frank et al., 2010) who stated that there is a necessity for a ‘global social movement of all stakeholders’ to promote ‘transformative professional education’ to improve health care (p. 3). To develop such education, academics and researchers need to interact and follow closely the needs of the field of practice. This was highlighted in the World Declaration on Higher Education for the Twenty-First Century: Vision and Action (UNESCO, 1998) which recommended higher education and research be available to most people and benefit society. In Norway, a main partner country in the COLAB consortium, authorities explicitly emphasise the strengthening of academic-practice research partnerships, i.e. that representatives from the field need to take part in all phases of a research process (Alstveit et al., 2017; Norwegian Research Council [NRC], 2012; White Paper no. 4 [2018–2019]). Based on this framework, the assumption is that partnership between academia and practice is necessary to improve services in health and welfare and services should be prepared/trained to work in this way. Such a partnership served as a starting point for the COLAB project. One of objectives of the COLAB project was to develop a training programme in collaborative practices. The aim was to improve collaboration competences and awareness and readiness for the innovation interventions described in Chapter 8. The target audience were frontline professionals working in criminal justice (CJS) and mental health services (MHS).

As will be illustrated in this chapter (and also Chapter 16 of this volume), it is not a given that the original plans for a project will work out as intended when implemented in practice. Although academics and frontline professionals may both have good intentions, they may also have very different views of the world. For example, academics may introduce what they regard as interesting collaboration models but these may not necessarily be models that are regarded by frontline professionals and users as relevant to their needs. Hence, there may be a gap between academics/researchers and frontline professionals in their different understandings of what is needed in the field. This gap may be much greater than expected and will be elaborated on in this chapter.

Aim of the Colab Project

The Change Laboratory Model (CLM) is basically an activity where participants from different systems and/or organisations are brought together to reflect on their working practices. The CLM has had great success as an intervention in a range of different contexts (see e.g. Engeström et al., 1996; Virkkunen & Newham, 2013). The CLM has potential in the CJS/MHS field (Hean et al., 2018), for professionals from across different contexts to explore each other’s perspectives and consequently reach new solutions for service delivery that is context-specific and user informed. A potential for innovation might arise during this collaboration process (see also Chapter 8 where the CLM is presented and elaborated).

In the COLAB project entitled Improving Collaborative Working Between Correctional and Mental Health Services (Hean, 2016), the aim was to validate that the Change Laboratory Model (CLM) was ready for implementation in CJS practice. As Hean (2016) argued in the proposal to the EU:

The Change Laboratory, highly successful internationally and in other clinical contexts, is a new idea in prison development, none as yet being applied to the challenges facing the MHS and CS. The wickedness, complexity and unpredictability of challenges facing interagency working in these secure environments means that piloting the CLM is premature and it must first be adapted to the MHS/CS context. (p. 2)

The COLAB project consists of several work-packages (WPs), and the present chapter focuses on one of these: the process of developing a training programme that would prepare professionals for their participation in interventions such as the CLM. Academics, together with a third-sector mentorship charity (non-academic partner), were responsible for designing a preliminary framework for training key skills in interprofessional collaboration for frontline professionals in the field. Various challenges arose during the collaboration which affected both the intentions of the project as a whole (EU proposal level) as well as the implementation of designing and carrying out the training programme (practice, real world level). Hence, contradictions between these levels occurred that played out in the collaborative efforts that took place and needed to be resolved.

Aim of This Chapter

The aim of this chapter is to contribute to an elaboration of central issues and possibilities involved in developing a training programme to improve collaboration in the intersection between the CJS and MHS. The main theme is to illustrate and discuss the gap between initial plans (proposal descriptions) and designing/planning the training programme in (real time) practice, as well as to reflect on the learning that took place in this process. The chapter provides a perspective on the issue of aligning academics’ and frontline professionals’ contributions, in terms of views, goals, roles and utility.

Theoretical Anchoring

The COLAB project deals with the partnership between academia and practitioners in the field with the object of improving collaborative dimensions of the work carried out by criminal justice system practitioners and those in mental health services. Two levels of interface are identified: (1) the EU proposal level, consisting of the intentions, objects, plans and deliverables constituting the structural framework of the original project proposal submitted and approved by the EU Commission and (2) the practice, real time level, involving the design and implementation of a training programme designed to improve the awareness and readiness for innovation and interventions among frontline professionals. In order to understand and analyse the two levels and the interplay between them, the concepts of community of practice and boundary practice (Wenger, 1998) are relevant. Interfaces connect different communities of practice, such as academia and those of CJS and MHS in our case, and the interactions between them may be regarded as a practice in itself, a boundary practice where learning takes place. According to Wenger (1998), such boundary practice may present sources of disagreement, misunderstandings and conflicts, but also opportunities for constructive collaboration and agreement, mutual knowledge development, and innovation and change. Several terms and concepts have been developed to nuance activities relevant to understanding the boundary crossing, such as boundary object and boundary work (Star & Greisemer, 1989; Wenger, 1998). In relation to the COLAB project, the training programme can be characterised as a boundary object connecting academics and frontline professionals, and the collaboration process that took place to design and implement the programme can be characterised as boundary work.

Social Innovation (SI), Interprofessional Learning and Collaborative Practice

Research partnerships between academia and the field of practice can also be understood as sites for innovation where new relationships for collaboration, different ways of knowledge production and designing/implementing change to improve services for the benefit of service users are created. The EU has launched social innovation (SI) as a strategy for designing new solutions to societal challenges (Bureau of European Policy Advisers, BEPA, 2011), which is particularly relevant for health and welfare services (Willumsen & Ødegård, 2015). A much-used definition of SI focuses upon how new ideas (products, services and models) meet social needs in the field and create new social relationships or collaborations (Murray et al., 2010; BEPA, 2011).

This means that SI has the potential to create solutions that can meet unmet social needs, within and across different welfare services. There may be innovations in the form of new products or services that help create social interaction, collaboration between people, and between people and organisations, services or businesses. In principle, SI contains the same components as other innovations (Bessant & Tidd, 2016), but the social aspect, creating social added value to deal with a social need, is not necessarily a prerequisite or consequence of all innovation. Hence, SI is regarded as relevant for the COLAB project as well as for the development of the training programme as the concept helps in understanding the complex and unpredictable collaborative interactions between academics and practice taking place to find new solutions to deficits in collaborative competences in frontline professionals working in CJS and MHS.

A literature review on innovation in health, education and welfare (Crepaldi et al., 2012) emphasises the relevance between innovation and collaboration. The authors characterise innovation in three dimensions: (1) the relational, with direct relationship between the user and the service provider, (2) the procedural, where innovation and dissemination is a continuous process and (3) the interactional, where generation and dissemination of innovation takes place within and between complex systems, contexts or areas of implementation. In other words, such innovations are characterised by being process-oriented and can include a variety of actors and their interactions at both macro and micro levels.

In exploring the relationship between SI and collaboration, it is relevant to distinguish between interprofessional learning and collaborative practice, although, in reality, learning and practice will intertwine. According to WHO (2010), ‘Interprofessional education occurs when two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes’ (p. 13). It is suggested by Ødegård (2006) that interprofessional collaboration may be perceived as a multilevel and multifaceted phenomenon. The wickedness of collaboration (Brown et al., 2010) may therefore be understood within this complexity. For example, some aspects of collaboration have to do with organisational factors such as ‘organisational culture’ and ‘organisational domain’. Group aspects, such as ‘communication between team members’ or ‘group leadership’, are also central in collaboration processes. Finally, everyone participating in collaboration processes will have their individual perceptions of what to expect of themselves and others. For example, some participants may be motivated to collaborate whereas others are not. This implies that when trying to establish collaborative practices, collaboration arrangements between frontline professionals on either side of the MHS/CJS fence have to take into account a range of perspectives that have to be reflected in the training programme.

Iversen and Johannessen (2020) suggest that there is a strong connection between interprofessional collaboration and innovation as interprofessional organisational practice is often an unclear practice where practitioners have to give up some of their usual practices to create a whole new collaborative situation. In this regard, interprofessional organisational practice becomes a new practice that emerges from ordinary and uniprofessional practices. To the extent that this occurs, such a practice will thus bear all the hallmarks of being an innovation practice (Iversen & Johannessen, 2020).

We can, therefore, recognise an innovative potential when professionals take part in collaborative processes creating a new situation, a boundary practice (Wenger, 1989) moving from their uniprofessional background into an interface with their interprofessional organisational practice. The training programme is regarded as a boundary object and boundary work has to be in progress. This includes collaborative and innovative processes, as well as mutual learning, all needed to complete the design and implementation of the training programme.

Co-Creating New Solutions

When designing and developing a training programme of interactions, the concept of co-creation can be applied in order to address the complex elements related to interactions, collaboration and innovation between academics and the people in the field. Co-creation is relatively new to the field, and there is no unified understanding of the concept (Røiseland & Lo, 2019). However, the concept can include relationships between public actors, civil third-sector representatives and the private sector. Collaborative governance, networking and partnership are central issues. Co-creation may function as a fruitful approach when alternatives related to service provision and problem solution are deemed necessary for improving organisational structures and services.

Bason (2010) emphasises two advantages with co-creation. One is diversity, whereby a wide range of ideas may emerge during co-creation processes, providing more opportunities to find good solutions. The other advantage is related to anchoring and execution. Both identification of problems and design of solutions and implementation will be more firmly rooted among individuals who actively participate in the design of proposals for new solutions. Under those circumstances, the opportunity to achieve positive change may become correspondingly greater. As Bason (2010) argues, ‘Co-creation can thus lead to radical solutions that overcome the silos, dogmas and groupthink that trap much of our current thinking, and can give us more and better outcomes at lower cost’ (p. 9).

According to Torfing et al. (2014), innovation processes are characterised by several phases: first, a problem identification phase, in which a problem is recognised and defined. In this phase and throughout the innovation process, those in the field, including both the users and service providers, can make a major and important contribution by explaining what the problem is and the ideas they have for solutions (Bason, 2010; Voorberg et al., 2015). Second, the development phase, consists of creative processes, where individuals try to think outside the box to find new ideas or possible solutions. During the third phase, the test phase, the best ideas will be tried out in practice and any adjustments can be made. Next is the fourth phase, the implementation phase: This phase identifies and selects the most suitable solution to be used. In this phase, relevant solutions risk not being prioritised. Finally, the selected idea/solution can be shared with others through upscaling and dissemination (the dissemination phase). The innovation process tends to be more circular in practice, which will be illustrated by our experiences.

Designing and Implementing the Training programme—An Illustration

In the COLAB, the training programme was considered an important outreach event of the project and was regarded as social innovation. Beneficiaries were to be professionals in mental health services, prison service professionals, service leaders, policy makers and training commissioners. Initially the training module (named WP3) was intended to raise awareness of the relevance and impact of collaborative and innovative practice, within and between services, and to offer international insights into reducing offender ill health. The content of the training was to be delivered as a workshop, once in Norway and once in the UK to non-academic partners and frontline professionals working in CJS and MHS regionally. The workshop was planned to be held at non-academic sites to promote access to a wider number of frontline staff.

In the development of the programme much of the contact between the academics (who had the lead in the development of the WP3) and frontline professionals had to occur during so-called secondments. Academics had secondments in the UK, with a third-sector mentorship charitable organisation. During the secondments, academics and frontline professionals had meetings to explore each other’s contexts, the potential for collaboration and what type of contributions were needed from collaborating partners to design and implement the training programme. For example, academics and professionals from practice discussed needs and opportunities to introduce collaboration/innovation training into the training of prison officers, on the one hand, and mentors on the other. In addition, the non-academic partners went on secondments for research experience in academic partner organisations to deepen their learning of research activities and knowledge development.

From Plans to Real Life—Illustrative Episodes

The COLAB proposal to EU contained several tasks and deliverables that also concerned the training programme. The deliverables, however, were plans that had to be discussed with the participants in the project—and especially the target group, professionals working in and outside the prison—to anchor ideas and discuss utility (cf. Bason, 2010; Torfing et al., 2014; Voorberg et al., 2015). The episodes below illustrate how different views played out in real life, and how ‘plans/intentions’ and ‘the practice reality’ became incompatible as contradictions arose during the co-creation process. According to the proposal, central tasks and deliverables for the training programme were the following:

-

To pilot the programme with a select group of frontline professionals in two national contexts.

-

To develop a framework, describing theory of Change Laboratory and other models of collaboration.

-

To organise and arrange training workshops to be delivered in the UK and Norway.

-

To evaluate the programme.

However, when operationalising these tasks and deliverables began, some obstacles and contradictions emerged. Some of these became apparent in a relatively quiet way, whereas others emerged abruptly and caused a major shift in the initial plans. Below we present some selected episodes to illustrate aspects of the collaboration and innovation processes taking place and how the differences between the academics and frontline professionals played out. These episodes show why there was a need to change the original plan. Academics appeared to perceive the EU application differently, including having an alternative understanding of ‘training’ than frontline professionals.

Episode 1: The COLAB Familiarisation Meeting: ‘Tell Them Who We Are’

The first meeting in the COLAB project, where all participants met, was hosted by one of the UK university Partners. Several members presented their future plans in the project, and participants discussed different options for realising the project’s aims. When a frontline professional from one of the COLAB practice partners was asked what the most important thing about the project was, seen from his point of view, he responded instantly: ‘Tell them who we are’. Elaborations on this statement led us to understand that frontline professionals did not necessarily know about each other, especially not the work being done by professionals across services.

Comment: This episode illustrates that frontline professionals do not seem to consider themselves as being part of a larger system of service providers, as other professionals from other services do not know much about them. They felt they were not on the service map. This might have had implications for the development of a training programme about collaboration.

Episode 2: ‘They Have Such Basic Needs’

During a meeting when the authors of this chapter were on secondment in the UK, a frontline professional made the following statement (referring to the service users): ‘They have such basic needs’. After some questions about this, we came to understand that some of the advanced collaboration ideas proposed in the COLAB application and strategic plan written by academic partners, were far off target when compared to the acute and immediate needs of the practice organisations with whom they were working. We were told that persons leaving prison, often after several years, have a whole range of basic problems that have to be dealt with, that they seldom have any money, lack housing, have no work, are in need for education and so forth. Many also have major health issues, physical and/or mental.

Comment: This episode illustrates the lack of alignment of goals between academics and frontline professionals. It seemed like academics also wanted the basic needs of the offenders to be addressed, but assumed that collaboration, as a process, was the way to achieve this end. Practitioners apparently were more interested in how that’s done; how offenders can function in daily life—focusing on the end point. The academics reflected on the professionals’ views and thought perhaps they weren’t so interested in collaboration after all because basic needs must be prioritised. The academics concluded that most of the practitioners were probably interested more in how they could manage risk and reduce reoffending, than in improving the abstract concept of collaboration.

Episode 3: ‘Forget Courses—People Do not Have Time’

Some months later, an academic and a frontline professional met while the professional was on secondment at one of the university COLAB partners. The academic asked if the secondee could maybe help with some input into the planned training programme that was going to take place—one workshop in Norway and one in the UK. The secondee looked at the academic for a few seconds and said: ‘Forget courses—people do not have time’. The academic was surprised, but also relieved. He was surprised because the secondee was so clear in her statement and relieved as he had been thinking a whole lot about how to design such a course in a realistic and useful manner and wondered about all the obstacles.

Comment: Through the deliverables presented in the EU application, the academics were committed to a ‘solution’ even before the project started. However, faced with the ‘reality’ described by the frontline professionals, the solution (training programme) was not an expedient option. In the professionals’ work situations, resources are scarce and trying to establish a training programme that almost nobody would be attending becomes irrelevant.

Discussion

The main aim of the present chapter has been to elaborate some issues and possibilities for developing a training programme to improve collaboration in the intersection between the CJS and MHS. As Hean et al. (2015a) argue, there is a lack of interprofessional training in the field of CJS and MHS. This calls for innovation, and particularly social innovation, which concerns new ideas that work to address pressing social needs (Murray et al., 2010; BEPA, 2011). This means that the innovation does not need to be a ‘product’, but rather new ways of organising services in the transition from prison back into society.

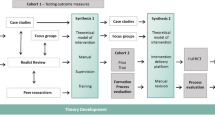

In general, innovation in the public and third sector should create values for the common good and add benefits to the community. Related to the development of the training programme, those aims require extensive dialogue with relevant partners and actors who would be allowed to participate and influence the various phases of the process (cf. Bason, 2010; Torfing et al., 2014; Voorberg et al., 2015). Hence, when developing a training programme, one has to take into consideration the unpredictable nature of such processes, which means that proposed measures might be changed. Based on the experiences during the collaboration and innovation process and in light of the theoretical framework introduced, we present an illustration (Fig. 17.1) that links different aspects of the process. The figure shows how the ‘training programme’ is connected to practice ‘needs’ and ‘perceived outcomes’.

A main theme of this chapter was to illustrate and discuss the gap between initial plans (proposal descriptions) and designing/planning a training programme in (real time) practice. The episodes above illustrate that the plans for training were challenged from the very start. The first episode (Tell them who we are) (see ‘1’ in Fig. 17.1) from the initial COLAB meeting does not explicitly illustrate this, but raises some interesting points on which to reflect:

The episode says something about the need for information exchange between professions and agencies in the CJS and MHS field, and between academics and professionals, about each other’s roles and functions. According to the frontline professional who brought this forward, it is not at all given that collaborating partners know about each other organisations and the services available for persons returning to society after imprisonment.

‘Tell them who we are’—seems quite easy, but how do we do it? Is mutual training across agencies the right way, as, for example, in workshops? How many frontline professionals do we reach by following the original plan for the training events? Could there be other learning activity options? The authors of this chapter think: Yes!!! The question really is whether generic training is the right approach to the needs in the field. Actually, training may be the wrong word completely. Maybe the academics tried to provide a solution to a problem that they knew little about. Retrospectively, should the academics’ tasks not have been to offer training programmes or other products, but rather to facilitate an exchange of knowledge and learning defined by the frontline professionals? In other words, the academics’ role should rather be to support change and not to provide predefined solutions. Such a change approach (see Chapter 8) would probably have opened up constructive dialogues and co-creation processes.

In Episode 2, They have such basic needs (see ‘2’ in Fig. 17.1), academics and frontline professionals may have perceived the needs of the CJS and MHS field very differently. Academics had, in the EU application, identified ‘collaboration’ as the target issue and wanted to introduce models that could potentially give positive outcomes for the different actors involved. Frontline professionals, on the other hand, were focused foremost on offenders’ basic needs, such as housing, food, clothing and getting an identity document. This was also highlighted in the vision of the volunteer organisation participating in COLAB and with the stated aim to build stronger, more integrated local communities by providing person-centred support for offenders or those who are at risk of offending, reducing reoffending and increasing life chances.

Episode 2 illustrates the boundary work that is going on in the mutual boundary practice in which academics and professionals are participating and the importance of them learning from each other (Wenger, 1989). The parties have to engage in dialogues, try to take different perspectives and sort out disagreements in order to create opportunities for development and change. In this regard, Episode 2 also illustrates that the academics’ focus had been mistaken. At a research level, academics can explore how collaboration between services will allow the basic needs of the offender to be more effectively addressed. The Voluntary organisation participating in COLAB is in fact a boundary crossing organisation in itself—in its remit and everyday practice. It aims to link offenders with various agencies and to improve collaboration in order to help offenders access services to meet their social needs. But what can we do to enhance this collaborative practice—when resources available to help offenders, at least in the UK, are very scarce? And how could these issues be approached in a training programme?

The third episode (see ‘3’ in Fig. 17.1)—Forget courses—people do not have time—is linked to the prior episode. Episode 3 was of major importance and represented a turning point for further development of ‘the training programme’. It became clear that an alternative to the suggested training programme had to be developed because frontline professionals unequivocally expressed that people would not have time to participate in a training workshop. Instead, the secondee suggested a ‘website of some sort’—as frontline professionals would easily access this when they had some minutes free from other duties. The idea of developing a website gave a more flexible solution and opportunities for all participants to contribute. The academics and frontline professionals had reached a more manageable solution as a result of their boundary work (Wenger, 1989). The first phase of the process of developing a training programme, developing the understanding of the challenges and defining central problems was difficult due to academics’ and frontline professionals’ different views and experiences. The academics felt obliged to follow the initial intentions set out in the EU proposal and the subsequent deliverables, whereas the practitioners were confident that these intentions would not work very well in practice.

The development of a website as a resolution to these challenges may be regarded as an innovation, a product innovation. Related to the phases of innovation processes and the involvement of users (Bason, 2010; Torfing et al., 2014; Voorberg et al., 2015) the change of direction of the initial ‘training programme’ is a good example of how participants influence collaborative and innovative processes of co-creating mutual efforts (Iversen & Johannessen, 2020; Willumsen & Ødegård, 2020). Based on this new starting point, the activity of the work package (WP3) moved into a development phase (Torfing et al., 2014), allowing for creative processes to find new ideas or possible solutions regarding design and content for the website. In order to involve most of the participants (project members in the COLAB project), they were all invited to contribute ideas to the website. Experts from one of the University´s IT Department were asked to join in the development of the website, and it was decided to construct a portal consisting of a menu including theoretical presentations, learning sections, podcasts (audio and video) and links to other relevant knowledge sources. The website is under construction and will be tested at the university college responsible for WP3. Later, after adjustments, the plan will be upscaled and fall to the permanent management by the host university of the COLAB project.

Social Innovation Through Collaboration and Co-Creation

Collaboration and co-creation are both central in our understanding of SI (see Fig. 17.1). SI simultaneously meets social needs and creates new social relationships or collaboration. In Fig. 17.1 this is illustrated in several ways. The ‘needs’ should be met, but as we have seen above, it is not a given how ‘needs’ are understood. Furthermore, SI both embeds and creates collaboration. Potentially, co-creation may take place in all relationships, and Hean et al. (2015a) refer to Bason (2010) and highlight four dimensions required for such development.

Consciousness

As illustrated by the episodes above, there is a need for different practice organisations, working with ex offenders, to inform each other, both as organisations and as professionals, about their various roles and responsibilities. This can be done in face-to-face courses, but there are other options as well. For example, as suggested by a frontline professional in Episode 3, an informative webpage could very well facilitate information exchange. Such creation however, raises many questions: Will each network configuration be different from organisation to organisation? If so, how do we help organisations map and connect with their social networks? How is the need for innovation or proactivity in the workforce encouraged through a webpage? And will a webpage actually provide useful knowledge for frontline professionals?

Capacity

It is suggested that the proposal for the training programme in the COLAB project somewhat overlooked the lack of capacity in some of the systems. Both Episode 2 and 3 demonstrate that it is more or less impossible for frontline professionals to engage in traditional training programmes—such as two two-day workshops. The reason is the serious lack of time practitioners in a clinical context have where there are calls for immediate action to help offenders receive basic services in the transition from prison back into society. There is no time for training, in the formal sense at least. It is possible that ‘learning’ rather than ‘training’ should have been the focus described in the original proposal. Learning at the individual and organisational levels is happening all the time. Still, as illustrated above in the Episodes 2 and 3, there is reason to argue that the development of a formal training programme and formal formative interventions is not the way forward because of lack of capacity. If this is the case, in what way can learning be supported? How do we achieve maximum learning with minimum resources as a prerequisite for a training programme?

Co-Creation

Ideally the idea of co-creation is relevant. But again, major lack of time and other resources will most likely limit co-creation processes taking place. It became very clear to us during our work in the COLAB project that some issues cannot be solved without basic discussions between participants to include diversity and obtain anchoring (Bason, 2010). How, for example, do different professionals, organisations and countries perceive ‘punishment and rehabilitation’? The answer to questions like this have massive implications for how collaborative practice unfolds and for what kind of knowledge development is needed in the interface between CJS and MHS. Basically, co-creation processes (as with learning) require a certain level of resources at the organisational level before co-creation can take place at the individual/relational level.

Courage

The last point concerns leadership. What is leadership in the field of CJS/MHS, and in contrast to that in academia, and what possibilities do leaders have to develop ‘bridges’ across sectors and professional domains? What kind of leadership is required to achieve the needed courage to develop these bridges? It seems quite clear that leaders in all systems (academia, CJS and MHS) will need to organise arenas for frontline professionals to meet and connect. Once in the same arena, these professionals could profit from developing a thorough understanding of collaboration as a phenomenon, by focusing on different aspects and levels of collaboration (cf. Ødegård, 2006).

Final Comments

A main idea with the COLAB project was to bring academia and the field of practice closer together, to build networks across ‘different worlds’. This is important as it is not a given that academics/researchers understand the needs of those working with offenders in the so-called real world like, as do the frontline professionals. A training programme was suggested (WP3) to bridge the interface and to foster interprofessional education to improve collaborative practice. However, as illustrated above, there appeared to be a divide on several levels, on a proposal level and on practice/real time level, as well as between the levels.

When writing proposals, researchers are required to describe and argue for their goals and deliverables, which means that in order to obtain their funding, they have to design concrete tasks and outcomes that are to be accomplished. The funding competition reinforces the effort to plan and anticipate solutions that give direction to the relevant research activities. Thus, when the researchers obtain funding and are carrying out their research, they feel obliged to comply with the accepted proposal in order to complete deliverables and obtain continuation funding. Such were the start-up conditions that directed what the focus and tasks were for the researchers who were responsible for the training programme (WP3). However, after examining the CJS/MHS interface and talking to different involved parties, the gap between the proposal and reality became obvious. Another aspect of the gap that became apparent is illumined in the theoretical framework of SI, collaboration and co-creation (Bason, 2010; Hean et al., 2015b) which emphasises that there are evolving, dynamic and unpredictable processes that cannot be foreseen. Given that a training programme should facilitate such processes, it is almost impossible to carry one out if you are trying to implement a predefined solution. There has to be opportunities for reconsideration. A third gap between theory and practice arises from the training versus reality of frontline practitioners’ preoccupation with offenders’ basic needs and access to services. Although the researchers were educated clinicians and were aware of offenders’ needs, they were primarily focused on delivering collaborative education and practice focused on how services could improve the practitioners’ collaborative work on a system level. They also felt obliged to fullfil the deliverable of a training programme outlined in their proposal.

As illustrated in this chapter, much boundary work took place (Wenger, 1998). Different views, goals and roles played out in dynamic interactions, and project participants arrived at an agreement to change the content of the deliverable. In particular, the question of the utility of the proposed training programme was intensely discussed, provoking a change. In retrospect, we can observe that a great deal of learning took place, such as learning about each other’s knowledge and views, about the interface and contexts of CJS/MHS, the various agencies responsible for offenders, learning about challenges regarding research and practice and the collaboration needed to improve services. We conclude that it takes courage and commitment to work out such boundary work, and it is important to be prepared for the challenge of this endeavour.

References

Alstveit, M., Willumsen, E., & Ødegård, A. (2017). Forskningssamarbeid mellom praksisfelt og akademia—en utforskning av dette samspillets rolle i kunnskapsutvikling. [Research collaboration between fields of practice and academia—An exploration of this interaction’s role in knowledge development]. In A. M. Støkken & E. Wilumsen (Eds.), Brukerstemmer, praksisforskning og innovasjon [User voices, practice research and innovation] (pp.149–167). Kristiansand: Portal Akademisk Forlag.

Bason, C. (2010). Leading public sector innovation: Co-creating for a better society. Policy Press.

Bessant, J., & Tidd, J. (2016). Innovation and entrepreneurship. Wiley.

Brown, V. A., Harris, J. A., & Russell, J. Y. (2010). Tackling wicked problems: Through the transdisciplinary imagination. Earthscan.

Bureau of European Policy Advisers (BEPA). (2011). Empowering people, driving change: SI in the European Union. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/librarydoc/empowering-people-driving-change-social-innovation-in-the-european-union. Accessed July 2020.

Crepaldi, C., De Rosa, E., & Pesce, F. (2012). Literature review on innovation in social services in Europe: Sectors of health, education and welfare services. INNOSERV Work Package, 1.

Engeström, Y., Virkkunen, J., Helle, M., Pihlaja, J., & Poikela, R. (1996). The change laboratory as a tool for transforming work. Lifelong Learning in Europe, 1(2), 10–17.

Frenk, J., et al. (2010). Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet, 376(9756), 1923–1958.

Hean, S. (2016). Improving collaborative working between correctional and mental health services. EU proposal, Proposal number: 734536, MSCA-RISE-2016, CO-LAB.

Hean, S., Staddon, S., Fenge, L., Clapper, A., Oxon, M. A., Heaslip, V., & Jack, E. (2015a). Improving collaborative practice to address offender mental health : Criminal justice and mental health service professionals’ attitudes toward interagency training, current training needs, and constraints. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education, 5, 1–17.

Hean, S., Willumsen, E., Ødegård, A., & Bjørkly, S. (2015b). Using social innovation as a theoretical framework to guide future thinking on facilitating collaboration between mental health and criminal justice services. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 14(4), 280–289.

Hean, S., Willumsen, E., & Ødegård, A. (2018). Making sense of interactions between mental health and criminal justice services: The utility of cultural historical activity systems theory. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 14(2), 124–141.

Iversen, H. P., & Johannessen, S. O. (2020). Et kompleksitetsteoretisk perspektiv på tverrprofesjonell organisasjonspraksis og innovasjonsprosesser [A complexity theoretical perspective on interprofessional organizational practices and innovation processes]. In E. Willumsen & A. Ødegård (Eds.), Samskaping [Co-creation] (pp. 247–259). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Murray, R. Caulier-Grice, J. and Mulgan, G. (2010) The open book of social innovation: London: Young Foundation. Accessed July 2020. Available at https://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/The-Open-Book-of-Social-Innovationg.pdf.

Norwegian Research Council (NRC). (2012). Innovasjon i offentlig sektor [Innovation in the public sector]. Oslo. NRC

Røiseland, A., & Lo, C. (2019). Samskaping—nyttig begrep for norske forskere og praktikere? [Co-creation—useful term for Norwegian researchers and practitioners?]. Norsk Statsvitenskapelig Tidsskrift, 35(1), 51–58.

Star, S. L., & Greisemer, J. R. (1989). Institutional ecology, `Translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s museum of vertebrate zoology. Social Studies of Science, 19(3), 1907–1939.

Torfing, J., Sørensen, E., & Aagaard, P. (2014). Samarbeidsdrevet innovasjon i praksis: en introduksjon [Collaborative innovation in practice: An introduction.]. In P. Aagaard, E. Sørensen, & J. Torfing (Eds.), Samarbejdsdrevet innovation i praksis. København: Jurist- og økonomforbundets forlag.

UNESCO. (1998). The world declaration on higher education for the twenty-first century: Vision and action. Paris: UNESCO. Accessed July 2020, Available at https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000141952.

Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J. J. M., & Tummers, L. G. (2015). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1333–1357.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Cambridge University Press.

White Paper no 4 (2018–2019). Langtidsplan for forskning og høyere utdanning 2019–2028. (Long-term plan for research and higher education 2019–2028). Oslo: Kunnskapsdepartementet/Ministry of Education and Research.

Willumsen, E., & Ødegård, A. (2015). Sosial innovasjon—fra politikk til tjenesteutvikling [Social innovation—from politics to service development]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Willumsen, E., & Ødegård, A. (2020). Samskaping [Co-creation]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

World Health Organisation (2010) Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. Geneva: WHO. Accessed July 2020. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70185/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf;jsessionid=6877DCD5E97EFE81E3B1C1399BCA73B3?sequence=1.

Ødegård, A. (2006, December 18). Exploring perceptions of interprofessional collaboration in child mental health care. International Journal of Integrated Care, 6. https://www.ijic.org/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ødegård, A., Willumsen, E. (2021). Developing a Training Programme for Collaborative Practices Between Criminal Justice and Mental Health Services: The Gap Between Intentions and Reality. In: Hean, S., Johnsen, B., Kajamaa, A., Kloetzer, L. (eds) Improving Interagency Collaboration, Innovation and Learning in Criminal Justice Systems. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70661-6_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-70661-6_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-70660-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-70661-6

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)