Abstract

Moving towards school improvement requires coming to understand what it means for a teacher to engage in ongoing learning and how a professional community can contribute to that end. This mixed methods study first classifies 48 primary schools into clusters, based on the strength of three professional learning community (PLC) characteristics. This results in four meaningful categories of PLCs at different developmental stages. During a one-year project, teacher logs about a school-specific innovation were then collected in four primary schools belonging to two extreme clusters. This analysis focuses on contrasting the collaboration and resulting learning outcomes of experienced teachers in these high and low PLC schools. The groups clearly differed in the type, contents, and profoundness of their collaboration throughout the school year. While the contents of teachers’ learning outcomes show both differences and similarities between high and low PLC schools, outcomes were more diverse in high PLC schools, nurturing optimism about the learning potential in PLCs. The study has implications for systematically supporting teacher learning through PLCs.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

10.1 Introduction

Given the major changes taking place in education over the past decades, professional development of teachers has become a necessity for teachers throughout their entire career (Richter, Kunter, Klusmann, Lüdtke, & Baumert, 2011). Historically, professional development activities of teachers were seen as attending planned and organized external professional development interventions, which generally assigned a passive role to teachers and was episodic, fragmented, and idiosyncratic (Hargreaves, 2000; Lieberman & Pointer Mace, 2008; Putnam & Borko, 2000). As such, these impediments and constraints limited the relevance of traditional professional development for real classroom practices (Kwakman, 2003).

Currently, many educational researchers argue that a key to strengthening teachers’ ongoing growth and ultimately students’ learning lies in creating professional learning communities (PLCs), where teachers share the responsibility for student learning, share practices, and engage in reflective enquiry (Sleegers, den Brok, Verbiest, Moolenaar, & Daly, 2013). Hence, this represents a shift towards ongoing and career-long professional development embedded in everyday activities (Eraut, 2004), where learning is no longer a purely individual activity but becomes a shared endeavour between teachers (Lieberman & Pointer Mace, 2008; Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, & Thomas, 2006). A significant body of research has attributed improvement gains, enhanced teacher capacity, and staff capacity at least in part to the formation of a PLC, thus demonstrating the relevance of teachers’ collegial relations as a factor in school improvement (Bryk, Camburn, & Louis, 1999; Darling-Hammond, Chung Wei, Alethea, Richardson, & Orphanos, 2009; McLaughlin & Talbert, 2001; Stoll et al., 2006; Tam, 2015; Vangrieken, Dochy, Raes, & Kyndt, 2015; Wang, 2015).

Previous studies on PLCs are rich in normative descriptions about what PLCs should look like (Vescio, Ross, & Adams, 2008). In reality, however, schools that function as strong PLCs and teachers that engage in profound collaboration with colleagues are few in number (Bolam et al., 2005; OECD, 2014). As such, it is not surprising that educationalists are keen to learn more about what characterizes schools in several developmental stages of PLCs and what teachers do differently in strong PLCs (Hipp, Huffman, Pankake, & Olivier, 2008; Vescio et al., 2008). Moreover, little is known about what teacher learning through collaboration in the everyday school context in PLCs looks like and which identifiable consequences collaboration can have for teachers’ cognition and practices (Borko, 2004; Tam, 2015; Vescio et al., 2008). This leads to three different methodological challenges: First, it is necessary to identify schools in different developmental stages of PLCs. Second, it is important to have rich descriptions of how teacher learning through collaboration in schools takes place. This is a complex process that includes mental, emotional, and behavioural changes. This necessitates a long-term observation of the process. Third, it is important to compare this process in schools at different stages of PLC in order to identify what makes the difference between these stages. To address these complex challenges, we designed a mixed method study. In the first place, it was important to identify what categories of schools, related to the developmental stages of PLCs, can be distinguished using the three core interpersonal PLC characteristics. Next, we selected four cases from contrasting types of PLC schools. A year-long study was set up to contrast the collaboration and resulting learning outcomes of experienced teachers in two high and two low PLC schools. Few studies in the field of PLCs have adopted a mixed methods approach (Sleegers et al., 2013), and studies about PLCs in primary education are lacking (Doppenberg, Bakx, & den Brok, 2012). This innovative mixed methods approach set in primary education wanted to explore, if the challenging methodological research goals were met and what the points of attention and pitfalls of this method were. In this respect, the study had both an empirical and a methodological aim.

10.1.1 PLC as a Context for Teacher Learning

In her seminal study about the conceptualization and measurement of the impact of professional development, Desimone (2009) argues that the core theory of action for professional development consists of four elements:

-

1.

Teachers experience effective professional development.

-

2.

This increases their knowledge and skills and/or changes their attitudes and beliefs.

-

3.

Teachers use these new skills, knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs to improve the contents of their instruction or pedagogical approach.

-

4.

These instructional changes foster increased student learning.

Many definitions of teacher learning and studies about the effects of professional development have confirmed that teacher change involves changes in cognition and in behaviour (Bakkenes, Vermunt, & Wubbels, 2010; Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002; van Veen, Zwart, Meirink, & Verloop, 2010; Zwart, Wubbels, Bergen, & Bolhuis, 2009). Many professional development programs follow an implicit causal chain and assume that significant changes in practice are likely to take place only after mental changes are present. However, this idea has been criticized and contested for quite some time by authors pointing out that a mental change does not necessarily have to result in a change of behaviour to be seen as learning, nor does a change in behaviour have to lead to mental changes (Meirink, Meijer, & Verloop, 2007; Zwart et al., 2009). As such, more interconnected models that adopt a cyclic or reciprocal approach have been presented (Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002; Desimone, 2009).

As for teacher behaviour as a learning outcome, teacher learning is strongly connected to professional goals that stimulate teachers to continuously seek improvement of their teaching practices (Kwakman, 2003). In this study, changes in teacher behaviour are thus described in terms of changes in teachers’ classroom teaching practices (e.g. changed contents of instruction, or changes in pedagogical approach). According to Bakkenes et al. (2010), it is important to also take into account teachers’ intentions for practices as learning outcomes, as these can be seen as precursors of change in actual practice. Regarding the mental aspect of learning outcomes, learning opportunities are expected to result in changes in teacher competence, seen as a complex combination of beliefs, knowledge, and attitudes (Deakin Crick, 2008; van Veen et al., 2010). For instance, Bakkenes et al. (2010) identified changes in knowledge and beliefs (new ideas and insights, confirmed ideas, awareness) and changes in emotions (negative emotions, positive emotions) in their research.

Studies acknowledge the difficulty of change, both in cognition and in behaviour (Bakkenes et al., 2010; McLaughlin & Talbert, 2001; Tam, 2015). Nevertheless, PLCs hold particular potential in this regard as documented by studies that link these collaborative learning opportunities to teacher change (Bakkenes et al., 2010; Hoekstra, Brekelmans, Beijaard, & Korthagen, 2009; Tam, 2015; Vescio et al., 2008). However, few authors focus on learning outcomes related to both cognition and behaviour in the same study.

Although a universally accepted definition of PLCs is lacking (Bolam et al., 2005; Stoll et al., 2006; Vescio et al., 2008), a common denominator can be identified: Collaborative work cultures are developed in PLCs, in which systematic collaboration, supportive interactions, and sharing of practices between stakeholders are frequent. These communities strive to stimulate teacher learning, with the ultimate goal of improving teaching to enhance student learning and school development (Bolam et al., 2005; Hord, 1997; Louis, Dretzke, & Wahlstrom, 2010; Sleegers et al., 2013; Vandenberghe & Kelchtermans, 2002).

Parallel to the diversity in definitions, studies about PLCs differ greatly with regard to the operationalization of the concept. However, several often-cited features of PLCs can be found, related to what Sleegers et al. (2013) identified as the interpersonal capacity of teachers. This interpersonal capacity encompasses cognitive and behavioural facets. Related to the cognitive dimension, many scholars point to a collective feeling of responsibility for student learning in PLCs (Bryk et al., 1999; Hord, 1997; Newmann, Marks, Louis, Kruse, & Gamoran, 1996; Stoll et al., 2006; Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008). Concerning the behavioural dimension, strong PLCs are characterized by reflective dialogues or in-depth consultations about educational matters, on the one hand, and deprivatized practice, on the other hand, through which teachers make their teaching public and share practices (Bryk et al., 1999; Hord, 1997; Louis & Marks, 1998; Stoll et al., 2006; Visscher & Witziers, 2004). Time and space are provided in successful PLCs for formal collaboration (i.e. collaboration that is regulated by administrators, often compulsory, implementation-oriented, fixed in time, and predictable) as well as informal collaboration (i.e. spontaneous, voluntary, and development-oriented interactions) (Hargreaves, 1994; Stoll et al., 2006). However, due to the conceptual fog surrounding the operationalization of the concept, empirical evidence documenting these essential PLC characteristics is lacking (Vescio et al., 2008).

While the idea behind PLCs receives broad support and many principals make strong efforts to promote collegial cultures in their schools, the TALIS 2013 study (OECD, 2014) showed that teachers still work in isolation from their colleagues for most of the time. Opportunities for developing practice based on discussions, examinations of practice, or observing each other’s practices remain limited. Teachers tend to share practices (Meirink, Imants, Meijer, & Verloop, 2010), but often through conversations that stay at the level of planning or talking about teaching (Kwakman, 2003) or through collaboration that lacks profound feedback among teachers (Svanbjörnsdóttir, Macdonald, & Frímannsson, 2016). Others have found that collaboration is often confined to solving problems that arise in the day-to-day practice (Scribner, 1999), while it is crucial in strong PLCs to also exchange and discuss teachers’ personal beliefs (Clement & Vandenberghe, 2000). It is necessary to distinguish between different forms and levels of collaboration as the benefits associated with it are not automatically achieved by any type of collaboration (Little, 1990). Studies highlight that collaboration between teachers should meet some standards in order to lead to profound teacher learning (Meirink et al., 2010). This is exemplified by the work of Hord (1986), who distinguished between two types of collaboration. On the one hand, she defined collaboration as actions in which two or more teachers agree to work together to make their private practices more successful but maintain autonomous and separate practices. On the other hand, teachers can work together while being involved in shared responsibility and authority for decision-making about common practices. These types are related to, respectively, the efficiency dimension of learning, where teachers mainly achieve greater abilities to perform certain tasks, and the innovative dimension, which results in innovative learning and requires the replacement of old routines and beliefs (Hammerness et al., 2005). While the former type of learning and collaboration is found in almost all schools, it is the latter type that characterizes practices in PLCs. As such, it is important to identify how collaboration in schools in diverse PLC development stages manifests. Studies that closely monitor interactions between teachers in primary education are lacking (Doppenberg et al., 2012).

10.1.2 The Study (Mixed Methods Design)

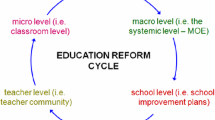

The above literature shows that our knowledge is still limited about the way a PLC can contribute to experienced primary school teachers’ changes in cognition and behaviour. A mixed methods research design is adopted in this study, in which we combine both qualitative and quantitative methods into a single study (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2009). This study is based on an explanatory sequential design (Greene, Caracilli, & Graham, 1989). We opted for this mixed methods design because of the different methodological challenges we faced. First, we wanted to identify different developmental stages of PLCs, in which primary schools can be situated (RQ1). For this challenge, we needed a substantial set of primary schools, in which quantitative data were collected. This quantitative method in a large sample of schools was necessary to identify different categories of PLCs based on the three interpersonal PLC characteristics: Collective responsibility, deprivatized practice, and reflective dialogue (Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008). A survey among the teaching staff of these schools provided the data for these characteristics. The aggregation of the data for each school enabled us to identify four meaningful and useful clusters that reflect different developmental stages of PLCs.

A second methodological challenge is to provide rich descriptions of teacher learning through collaboration on a long-term basis and to understand how this differs between different developmental stages of PLCs. To meet this challenge, the method of following-up on outliers or extreme cases is then used in the qualitative part of this study (Creswell, 2008). We compare the type and contents of the year-long collaboration of experienced teachers about a school-specific innovation in four schools in extreme clusters (high presence versus low presence of PLC characteristics; RQ2). We also compare how teachers in these four schools look back at the collaboration and how they assess the quality of the collaborative activities (RQ3). Furthermore, we investigate how PLCs can contribute to experienced teachers’ learning (RQ4), more particularly to cognitive and behavioural changes, thus deepening the general framework of learning outcomes of Bakkenes et al. (2010). We focus on experienced teachers as this allows us to gain insight into learning outcomes that go beyond merely mastering the basics of teaching (Richter et al., 2011). Using a longitudinal perspective through digital logs enables us to focus on differences between high and low PLC schools in the evolution of collaboration and learning outcomes throughout one school year. The choice of using digital logs as a qualitative method was inspired by the study of Bakkenes et al. (2010). In this study, digital logs were used to ask teachers to describe learning experiences over a period of one year. This procedure displayed several strengths: The provision of rich descriptions of teacher learning that enabled the researchers to differentiate between (different) experiences of teachers, an efficient way of collecting qualitative data with the same time-intervals from a relative large number of participants, the opportunity to collect similar information (similarly structured with different time-intervals) and comparable data across different schools, and the opportunity to collect longitudinal data over a one-year period.

The methods and results for the quantitative and qualitative research phase are discussed separately. The findings are interpreted jointly in the discussion.

10.2 Quantitative Phase

10.2.1 Methods

An online survey was completed by 714 Flemish (Belgian) primary school teachers from 48 schools. On average, 15 teachers per school completed the questionnaire, with a minimum of 3 teachers in each school. The mean school size was 21 teachers (range: 6–42 teachers) and 298 students (range: 100–582 students). As for the teachers, the sample included 86% female teachers, which is similar to the male-female division in Flemish primary schools. Teachers’ experience in the current school ranged from 1 to 38 years (M = 13 years), while the experience in education varied from 1 to 41 years (M = 16 years).

To measure the interpersonal PLC characteristics (Sleegers et al., 2013), we used three subscales of the ‘Professional Community Index’ (Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008): collective responsibility, deprivatized practice, and reflective dialogue (Vanblaere & Devos, 2016). A summary of the main characteristics of the scales can be found in Table 10.1.

As a first step in the analysis, aggregated mean scores for the three PLC characteristics were computed. The intraclass correlations of a one-way analysis of variance with a cut-off score of.60 (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) were used to determine that it was legitimate to speak of school characteristics (see ICC in Table 10.1). Then, a two-step clustering procedure was performed with SPSS22 to attain stable and interpretable clusters that have maximum interpretable discrimination between the different clusters (Gore, 2000). First, the three aggregated PLC characteristics were standardized and entered in a hierarchical cluster analysis, using Ward’s method on squared Euclidean distances, which minimizes within-cluster variance. Second, the cluster centres from the hierarchical cluster analysis were used as non-random starting points in an iterative k-means (non-hierarchical) clustering procedure. This process permitted the identification of relatively homogeneous and highly interpretable groups of schools in the sample, taking the three PLC characteristics into account.

10.2.2 Results

In the first step of the cluster analysis, the cluster division had to explain a sufficient amount of the variance in the three PLC characteristics. We estimated cluster solutions with two to four clusters and inspected the percentage of explained variance in each solution (Eta squared). As only the four-cluster solution explained more than 50% of the variance in all three variables, the other cluster solutions were not considered further. Step two of the process was applied to the four-cluster solution, which yielded four clearly distinct clusters with sufficient explained variance (collective responsibility (.68), deprivatized practice (.63), and reflective dialogue (.77)). Table 10.2 presents a detailed description of these clusters, including standardized means, standard deviations, and descriptions.

Cluster 1 consisted of only 4 schools (8.4%) of the research sample. These schools reported high scores in all three interpersonal PLC characteristics, including deprivatized practice. This separates them from the schools in cluster 2 (n = 11, 22.9%), in which the scores were high for collective responsibility and reflective dialogue, but only average for deprivatized practice. This implies that teachers rarely observe each other’s practices in cluster 2, while this occurs every now and then in the first cluster. Cluster 3 consisted of 22 schools (45.8%) scoring rather average on all three PLC characteristics. In these schools, teachers feel more or less collectively responsible for their students, engage in reflective dialogue every now and then, but rarely observe each other’s teaching practice. Cluster 4 was also represented by 11 schools (22.9%) and showed a low presence of PLC characteristics.

10.3 Qualitative Phase

10.3.1 Case Selection and Method

In this part of the study, a multiple case study design was adopted. A purposeful sampling of extreme cases was carried out (Miles & Huberman, 1994), involving schools from cluster 1 with a strong presence of all PLC characteristics (high PLC) and schools from cluster 4 with a low presence of all PLC characteristics (low PLC). These schools were contacted, and we inquired about plans to implement an innovation or change during the following school year with implications for teachers’ ideas, beliefs, and teaching practices. The final sample consists of four schools (two of high PLC and two of low PLC) that met this criterion and where teachers agreed to participate in the study.

The sample consists of 29 experienced teachers with at least five years of experience in education and three years of experience in the current school, based on Huberman’s (1989) classification. The only exception is school D, where a teacher with only two years of experience in the current school also participated, since this teacher played a central role in the ongoing innovation. In school A, B, and D, all experienced teachers took part in the study. In school C, however, six of the experienced teachers involved in the innovation were randomly selected by the principal. Table 10.3 presents some context information on the four selected schools.

Teachers in the participating schools were asked to complete digital logs at four time-points over the course of one school year, i.e. at the beginning of the school year and at the end of each of the three trimesters (December, April, and June). In total, we received 109 completed logs (response rates ≥90%, see Table 10.3). The first log was intended to provide the authors with more background information about the antecedents, implementation, and consequences of the innovation. The focus of this study was on the remaining three logs (n = 80), in which teachers were asked about their collaborative activities concerning the innovation during that trimester and the resulting learning outcomes. More specifically, teachers were first asked to list the different kinds of collaborative activities they had actively engaged in and to describe the nature and contents of these activities. Teachers had the option to fill in any type of activity while being provided with some examples (e.g. discussing the innovation at a staff meeting, jointly preparing and evaluating a lesson with regards to innovation, informal discussion with colleagues during break-time). They were also instructed to list activities separately, if the stakeholders differed. Teachers could list from one to ten different kinds of activities. For each activity they undertook, the teachers received brief, structured follow-up questions about the collaboration process. Each question had to be answered separately, prompting the teachers to provide additional information about the stakeholders in the described collaborative activity, who initiated it, where and when it took place, how frequently it occurred, and any constraints they experienced. Secondly, teachers were asked in each log to reflect upon what they had learned through this collaboration and to describe the contribution to their own classroom practices and their competence as a teacher. This was an open question, but teachers were nonetheless instructed to mention how each collaborative activity had contributed to these outcomes. Responses to this question varied from 10 to 394 words. In the final log, all teachers were asked to briefly discuss their general appreciation of the quality of their own collaboration over the past year. Responses to this question varied from two-worded expressions (e.g. ‘Great collaboration!’) to 233 words.

The logs were coded using within- and cross-case analysis (Miles & Huberman, 1994). The first round of data analysis examined each separate log, which was treated as a single case. Considerable time was spent on the process of reading and re-reading the logs, as they were submitted throughout the year, in order to assess the meaningfulness of the constructs, categories, and codes (Patton, 1990). If the log of a teacher was unclear, contributions of other teachers at the school were searched through for possible clarifications. Additional information from teachers was requested by e-mail or telephone, when needed, to ensure a correct interpretation.

A coding scheme was developed based on the theoretical framework and based on themes emerging from the data itself. The categories used to identify features of collaboration were: (1) type (discussions about practice, teaching together or sharing teaching practices, working on teaching materials, practical collaboration, and no collaboration), (2) structure (formal and informal), (3) stakeholders (the entire school team, a fixed sub-team, interactions between two or three teachers, and external stakeholders), and (4) duration (frequency and recurrence throughout the year). The reflections of the teachers on the collaboration at the end of the year were divided into positive or negative impressions based on indicators of appreciation in the language used. The coding framework used to categorize the outcomes of the collaboration: No learning outcome, changes in knowledge and beliefs (new ideas and insights, confirmed ideas, awareness), changes in practices (new practices, intentions for new practices, alignment), changes in emotions (negative emotions, positive emotions), and general impression of contribution. Each log was assessed with regard to the presence of these outcomes. Related to the coding of ‘new practices,’ it should be noted that logs were only coded as containing new practices when these changes were a consequence of the collaboration between teachers. Nevertheless, certain collaborative activities, in essence, also implied new classroom practices, even though they were not coded as such (e.g. co-teaching with coaches (HIGH B) and lesson observation and workshops (LOW D)). A second researcher, who was not familiar with the study or participating schools, was trained to grasp the meaning of the coding and coded 30% of the logs (n = 24). The intercoder-reliability was.89, which is in accordance with the standard of.80 of Miles and Huberman (1994).

Once all separate logs were coded, data from teachers within the same school were combined to provide an overview of the collaboration and learning outcomes at each school in the first, second, and third trimester. Similarly, teachers’ general appreciation of the quality of their own collaboration, as written down in the final log, was described for each participating school. This resulted in a school-specific report that summarized all findings for each school. As a member check the school-specific report was sent to the principal, accompanied by the request for discussing this report with their teachers and to provide us with feedback. This allowed principals and teachers to affirm that these summaries reflected the processes that occurred throughout the school year at their school. No alterations were requested, thus confirming the completeness and accuracy of the study. Next, the within-case analysis was extended by comparing the logs over time for each school. Fourth, a cross-case analysis was conducted, where the four schools were systematically compared with each other to generate overall findings that transcend individual cases and to identify similarities and differences between high and low PLC schools; Nvivo10 was used to organize our analysis.

10.3.2 Results

10.3.2.1 Collaboration Between Teachers

Our results indicate that collaboration was shaped in a very different way in the two schools selected from the cluster with a high presence of PLC characteristics (high PLC) and in the two schools from the cluster showing a low presence of PLC characteristics (low PLC). In the following paragraphs, the differences in the type of collaborative activities will be explained more in depth, with an explicit focus on the evolution of practices throughout the school year.

A first major difference between the high and low PLC schools lies in teachers making their teaching public by engaging in deprivatized practice, or working on teaching materials together in high PLC schools. However, the execution of these shared practices differed between both high schools. In HIGH B, several teachers were appointed as coaches, specifically for the implementation of the innovation. Each coach was paired with one or two teachers from adjacent grades, and they engaged in several structured cycles of collaboration. In the first and second trimester, coaches and teachers worked on lesson preparations together or in consultation, by frequently discussing the design, contents, and pedagogical approach of the lessons that were taught related to the innovation. These lessons were then taught through co-teaching or taught by one teacher and observed by the other. At the initiative of several teachers using the innovation in their daily practice, a sub-team of teachers in HIGH A developed classroom materials together throughout the school year. In addition, HIGH A was visited in the third trimester by a teacher from a school working with the same innovation as well as by a group of teachers interested in implementing the innovation in the future. Artefacts, classroom practices, information, and findings about the implementation of the innovation were shared with these external stakeholders. As such, these practices illustrate that deprivatized practice can occur both within schools and between schools. This is in contrast with the low PLC schools, where such practices were virtually non-existent, apart from a one-time lesson observation in LOW D between two teachers, with no real follow-up.

A second difference relates to practical collaboration between teachers. In the low PLC schools, it was common for teachers to engage in basic practical collaboration. This was especially the case throughout the school year in LOW C, where teachers from the same grade, for instance, visited the library together or assessed students’ reading level together with the special needs teacher. Remarkably, this is even the only type of collaboration that multiple teachers of LOW C mentioned in the third trimester of the school year. Several teachers in LOW D mainly had practical interactions at specific moments (e.g. at the end of the school year), or with external stakeholders (e.g. a volunteer, who taught weekly chess lessons in two classrooms).

Third, our results show that while teachers in both high and low PLC schools participated in discussions about how to incorporate the innovation in their daily practice, the extent of these conversations differed noticeably. Teachers in all schools described dialogues with specific partners (i.e. teachers of the same grade, adjacent grades, or coach) about general and practical matters. In low PLC schools, most interactions were limited to these fixed partnerships, and discussions about the innovation with the entire team at staff meetings were mentioned infrequently in the logs of teachers, indicating a low ascribed importance of these meetings. Structured sub-teams of teachers were largely absent in low PLC schools, with the exception of two working groups in LOW D. These working groups were launched at the end of the school year, met once, and were focused on practical arrangements and requests of teachers for the following school year. In contrast, in high PLC schools, conversations about day-to-day problems or questions involving the innovation were also frequently discussed spontaneously with colleagues in between lessons (or at lunch-time) with whoever was present. Teachers also systematically brought up that the innovation was discussed during staff meetings throughout the school year. Both high PLC schools had a structured sub-team of teachers (coaches in HIGH B, teachers using the innovation daily in HIGH A). Additionally, teachers in these schools exchanged experiences and expertise with teachers from other schools implementing a similar innovation and receiving external assistance, either on a structural regular basis (HIGH B) or in a one-time workshop (HIGH A).

Furthermore, most dialogues occurred in the low PLC schools in the first trimester, after which the frequency of conversations about the innovation diminished drastically. Contrarily, dialogues in high PLC schools were maintained across the school year.

The contents of dialogues usually remained at a superficial level in low PLC schools, as illustrated by teachers in LOW C, who stated that initial staff meetings were about making arrangements and expressing expectations regarding the innovation, while this evolved throughout the school year into reminders for teachers to implement the innovation.

However, teachers in the high PLC schools did engage in several kinds of profound and reflective dialogues. For instance, each coach in HIGH B completed a structured evaluation with their partner each time they had jointly prepared and taught a lesson. At the end of the school year, they reflected upon the implementation of the innovation and the link between the innovation and other teaching contents. Additionally, both sub-teams of teachers in the high PLC schools had several formal meetings each trimester as well as informal discussions during breaks or outside of school hours, aimed at monitoring and moving the innovation forward. Furthermore, staff meetings with the entire team were used as a way to facilitate planning, but most importantly to share teachers’ beliefs, opinions, and experiences.

In conclusion, the results show several substantial differences between the high and low PLC schools in their collaboration. While teachers in all schools engaged in day-to-day conversations about the implementation of the innovation, these dialogues were more sustained throughout the school year and more spread throughout the entire team in high PLC schools. Additional collaboration was also of a higher importance in high PLC schools compared to low PLC schools, involving activities, such as deprivatized practice, discussions with the entire team, developing teaching materials, and having profound conversations about beliefs and experiences. High PLC schools also undertook meaningful partnerships with external stakeholders, while low PLC schools regularly engaged in practical collaborations. With regard to the initiators of collaboration, high PLC schools appear to make good use of both structured formal collaboration and spontaneous informal collaboration, while the initiative of collaboration often remained with individual teachers in low PLC schools.

10.3.2.2 Learning Outcomes from the Collaboration

With regard to the final qualitative research question, teachers mentioned a wide range of outcomes when asked what they had learned through interacting with their colleagues. In total, ten different types of outcomes were distinguished in teachers’ logs. Table 10.4 provides an overview of the occurrence of the outcomes throughout the school year. The communalities and differences between the contents and the diversity of learning outcomes in high and low PLC schools are discussed and illustrated in the following paragraphs.

10.3.2.2.1 Content of the Outcomes

We first describe the outcomes that are marked as frequently mentioned in Table 10.4 (i.e. general impression of contribution, no outcome, new ideas, new practices, and changes in alignment), after which we move on to a brief discussion of the remaining outcomes (i.e. positive emotions, intentions for practices, awareness, negative emotions, and confirmed ideas).

Teachers from both high and low PLC schools mentioned that their collaboration somehow contributed to their professional growth. This positive impression is most consistent throughout the school year in the high PLC schools. However, not all teachers had the impression that the collaboration made meaningful contributions to their competence or practices, especially in low PLC schools. Logs from the second and third trimester in these low PLC schools show a lack of learning outcomes stemming from collaboration for a considerable group of teachers. Several teachers merely explained their collaborative activities again or mentioned what students had learned, but failed to provide evidence of their own learning outcomes.

Our results indicate that new ideas, insights, and tips as a learning outcome occur consistently in high and the low PLC schools throughout the school year, as only the logs of the third trimester in LOW D did not contain any new ideas. Here, we did not find any systematic differences between high and low PLC schools.

New practices, as a result of collaboration, were mentioned several times in the high PLC schools. In the low PLC schools, no profound changes were reported. New practices at a basic level were the most frequently mentioned outcome for LOW C in the first two trimesters, usually as a result of practical collaboration, which was strongly present at this school. Teachers in LOW D hardly mentioned new practices of any nature.

Furthermore, our results suggest differences between schools regarding the stakeholders in aligning practices between teachers. This type of outcome transcends the individual classroom practice of teachers and refers to classroom practices being geared to one another. However, these results should be interpreted with caution as changes in alignment occurred systematically in two schools only (HIGH A, and LOW D). In the high PLC school, teachers spoke of aligning practices for the whole school during the school year, for example: “It was a useful meeting to exchange experiences and to find common ground. Practices were geared to one another.” (Teacher, HIGH A). In LOW D, this practice was not spread throughout the school as most of the statements could be attributed to two teachers, who consistently mentioned aligning practices throughout the year. One teacher explained: “I got a clear image of what the testing period in grades 4 and 6 looks like. This allowed us to discuss the learning curve we want to implement: increasing difficulty level, what is expected in the next year,….” Only at the end of the school year, teachers mentioned aligning practices for the entire school in a one-off working group.

Although not mentioned frequently, it is noteworthy that positive emotions were only reported in the high PLC schools. Several teachers expressed throughout the year that they felt supported by their colleagues, coaches, or principal, and that they were glad that help from colleagues was available.

Finally, our results show that collaborative interactions between teachers only rarely lead to negative emotions (e.g. feelings of concern and doubt about the role as coach for the following years) or confirmed ideas, in both high and low PLC schools.

10.3.2.2.2 Diversity of the Outcomes

Looking at the diversity of reported outcomes in schools (see Table 10.4), teachers in the high PLC schools, on average, mentioned multiple of the outcomes described above as a result of collaboration during each trimester. Hence, teachers from high PLC schools have, in general, attained more varied learning outcomes per trimester than teachers in low PLC schools. Over the three trimesters, teachers in HIGH A, and HIGH B consistently mentioned multiple outcomes per trimester and thus combinations of learning outcomes. In HIGH B, the full range of outcomes was reached, as every outcome was mentioned by at least one teacher at some point in time during the school year.

However, outcomes were less diverse in low PLC schools. In general, these teachers did not describe any changes in their competence or practices, or indicated just one outcome (e.g. new practices, new ideas). This trend was present throughout the year in LOW C, while outcomes were more diverse in the first trimester in LOW D, but then diminished drastically in the second and third trimester.

10.4 Discussion and Conclusion

Combining quantitative and qualitative data in this study, allowed us to ‘dig deeper’ into the question of how PLCs function and contribute to teachers’ learning outcomes, resulting in generalizable findings as well as detailed and in-depth descriptions of key mechanisms in several schools that were followed throughout an entire school year. In particular, we quantitatively examined, which types of primary schools can be distinguished, based on the strength of three interpersonal PLC characteristics. This resulted in four meaningful categories of PLCs at different developmental stages. Subsequently, we qualitatively documented the collaboration and resulting learning outcomes of experienced teachers related to a school-specific innovation over the course of one school year at four schools at both ends of the spectrum (high PLC versus low PLC). Our analyses showed the following key findings:

The first research question was aimed at analysing into which categories primary schools could be classified based on the strength of three interpersonal PLC characteristics (collective responsibility, reflective dialogue, and deprivatized practice). Cluster analysis revealed four meaningful categories, reflecting different developmental stages: High presence of all characteristics (8.4% of schools); high reflective dialogue and collective responsibility, but average deprivatized practice (22.9%); average presence of all characteristics (45.8%); and low presence of all characteristics (22.9%). This confirms that there are considerable differences between schools in the extent to which they function as a PLC, with most schools in the stage of developing a PLC (Bolam et al., 2005). This classification is in line with previous categories found for Math departments in Dutch secondary schools that also identified a high PLC cluster, a low PLC cluster, a deprivatized practice cluster, and an average cluster (Lomos, Hofman, & Bosker, 2011).

With our second research question, we wanted to clarify what characteristics of collaboration differed throughout the school year in schools with a high and low presence of all PLC characteristics, when dealing with a school-specific innovation. In this regard, our results confirmed previous studies that point to the frequent occurrence of basic day-to-day discussions about problems and teaching (Meirink et al., 2010; Scribner, 1999). However, based on our knowledge, this study is one of the first ones to pinpoint differences between the high and low PLC schools in these lower levels of collaboration, such as storytelling and aid (Little, 1990). We add to the literature by concluding that teachers in low PLC schools talk about an innovation mainly at the start of the school year, albeit with varying frequencies. The occurrence of these dialogues strongly diminished throughout the school year at low PLC schools, while they were more common and sustained at the high PLC schools. In some cases, the contents of the dialogues can explain, why conversations were mostly limited to the first trimester (e.g. conversations about “students’ transition between grades, fieldtrips, planning of the year or tests, and communal year themes” in LOW D). Furthermore, dialogues at the low PLC schools occurred mostly with a fixed partner, whereas spontaneous conversations spread throughout the team were equally found at the high PLC schools. Hence, this suggests that characteristics that are mainly associated with higher order collaboration in successful PLCs (e.g. spontaneous and pervasive across time (Hargreaves, 1994)), are also present in ongoing basic interactions in high PLC schools. Additionally, only teachers at the low PLC schools mentioned practical collaboration with colleagues, for example, visiting a library together.

In contrast, collaboration at the high PLC schools went well beyond these day-to-day conversations or practical collaboration, as we expected based on research of, for instance, Bryk et al. (1999), Little (1990), and Bolam et al. (2005). In this regard, our study shows that deprivatized practice can occur with a variety of stakeholders, as teachers opened up their classroom doors and made their teaching public, either for teachers from their own school (HIGH B) or teachers from other schools (HIGH A). In relation to the latter, it is remarkable that both high PLC schools were strong in building partnerships with other schools and sharing their experiences as well as making use of external support. This is in line with the idea that external partnerships can help a PLC to flourish (Stoll et al., 2006). Teachers were also responsible for developing concrete materials, such as lesson plans, that could be used by the team, which increases the level of interdependence in the team according to Meirink et al. (2010).

Furthermore, spontaneous as well as regulated reflective dialogues in small groups occurred. These included in-depth spontaneous reflections with an intention of improving practices throughout the entire school. Moreover, the importance of staff meetings and sub-teams as collaborative settings (Doppenberg et al., 2012) was confirmed for the high PLC schools. In particular, staff meetings were much more meaningful at the high PLC schools compared to low PLC schools, as meetings took place throughout the school year and left room for discussing teachers’ beliefs, experiences, and suggestions. Clement and Vandenberghe (2000) and Achinstein (2002) previously pointed to the importance of discussing beliefs for continual growth and renewal in schools. A possible explanation for the finding that collaboration often does not go beyond practical problem-solving and avoids discussions about beliefs at low PLC schools can be found in the field of micro-politics. Collaboration that includes talk about values and deeply held beliefs, requires a safe environment of trust and respect, but also increases the risk of conflict and differences in opinion (Johnson, 2003). According to Achinstein (2002), it is important to balance maintaining strong personal ties, on the one hand, while sustaining a certain level of controversy and differences in opinion, on the other hand.

It is interesting that both high PLC schools proactively installed a structured sub-team of teachers, intended to steer and monitor the innovation. Regardless of whether such a team is put together for the innovation (HIGH B), or existed previously (HIGH A), we think that this contributed greatly to the overall quality and continuation of collaboration at these schools, as interactions were not merely left to the initiative of individual teachers. This complements the finding of Bakkenes et al. (2010) and Doppenberg et al. (2012), who suggested that organized learning environments are qualitatively better than informal environments.

The third research question covered differences in teachers’ appreciation of the general quality of their own collaboration. Remarkably, almost all teachers expressed a positive feeling about the collaboration, even in low PLC schools. This leads to an important methodological suggestion, namely that caution is required when dealing with teachers’ perceptions of the quality of collaboration as in indicator of actual collaboration, because this can be an over-estimation of reality. A more accurate picture can be obtained, for example, by inquiring about the type and frequency of collaboration.

The final research question dealt with the differences in learning outcomes between the high and low PLC schools. The most striking difference is located in the diversity of outcomes that teachers reported. - More specifically, learning outcomes were overall more diverse and numerous throughout the school year for the high PLC schools compared to the low PLC schools. The sharp drop in learning outcomes in one of the low PLC schools in the second trimester might be due to the decrease of dialogues throughout the year in the low PLC schools. In relation to the contents of the learning outcomes, our results add to the general learning outcomes framework of Bakkenes et al. (2010) by expanding it to learning outcomes resulting solely from collaboration and exploring the occurrence of the outcomes at high and low PLC schools. Unsurprisingly, not all collaboration resulted in learning outcomes, especially at the low PLC schools. However, the logs showed that both at the high and low PLC schools, collaboration frequently led to new ideas and insights, or a general impression that the collaboration had made a contribution. This is in line with the finding of Doppenberg et al. (2012), who noted that teachers often mention implicit or general learning outcomes. A possible explanation for this is that both outcomes are fairly easy to achieve and non-committal towards the future. Another possibility is that teachers mainly associate learning with changes in cognition or the general impression of having learned something; it is also imaginable that it was difficult for teachers to express what they had learned exactly, leading them to report a general impression. Nevertheless, new practices in line with the ongoing innovation also emerged. At the low PLC schools, new practices were limited, or mainly identified, as practical changes in classroom practices, or what Hammerness et al. (2005) referred to as ‘the efficiency dimension of learning.’ Only the collaboration at the high PLC schools seemed powerful enough to also provoke profound changes in practices or the innovative dimension of teacher learning (Hammerness et al., 2005). Additional intentions for practices were mainly identified at the end of the school year. Changes in emotions, confirmed ideas, changes in alignment, and awareness occurred rarely as learning outcomes. In conclusion, our results confirm that collaboration can result in powerful and diverse learning outcomes (Borko, 2004), but that this is not an automatic process for all collaboration (Little, 1990).

As with all research, there are some limitations to this study that cause us to be prudent about our findings. First, an explanatory sequential mixed methods design was used in this study. As such, our case studies were purposefully sampled based on available quantitative data. While this has many advantages, it implied that we had certain expectations regarding the collaboration in these schools beforehand, influencing our interpretation of the qualitative results. As such, we believe in the value of several precautions to limit this possible bias, as explained in the methods section (e.g. member check, the use of double-coding).

Second, the qualitative results are based on digital logs completed by teachers throughout the year. Individual perceptions were combined with the logs of other teachers from the school, when possible (e.g. for collaboration), and individual listings were seen as an indicator of the ascribed relevance of activities, but our study nevertheless relied heavily on self-report. Furthermore, some teachers did not provide detailed information about the nature of changes in practices or cognition resulting from the collaboration, especially at low PLC schools. As the logs were more elaborate at high PLC schools, this might have influenced our findings. In this regard, future research could add useful information by combining digital logs with interviews, or observations of collaboration and resulting changes to obtain more similar information from all teachers. Moreover, this study generally refrains from linking specific collaboration to certain outcomes, because not all teachers described their learning outcomes separately for each collaborative activity. Bearing in mind that it can be difficult for teachers to pinpoint what they have learned exactly, future research could address this gap.

Third, the case studies offer insight into experienced teachers’ collaboration and learning at four primary schools that were selected through extreme case sampling and have rather unique profiles. Furthermore, the high average in years of teaching experience at the school, combined with the fairly small school sizes, point to rather long-term relationships between the participating teachers, which likely played a role in our results. Additionally, some collaboration with beginning teachers was mentioned by experienced teachers, but we have not gathered complementary data from beginning teachers directly. Hence, it would be useful for further research to use larger samples of teachers in schools spread over the four clusters.

Fourth, the scope of this study was narrowed down to the interpersonal aspect of PLCs for the cluster analysis. Future studies could be directed at providing a broader picture, which takes elements of personal and organizational variables into account (Sleegers et al., 2013).

Despite these limitations, we think that our mixed method design offers several opportunities of future research in school improvement. A main advantage of our design is that it provides a method of identifying contrasting cases in interpersonal capacity and of better understanding why there is a difference in the interpersonal capacity between schools. An important challenge in school improvement research is the identification of different stages of school capacity. It is important to realize that schools differ in their key characteristics of what makes a school great. Our study provides a method to identify different stages in the interpersonal capacity of schools. A similar method can be used to identify different stages in other key characteristics of schools. The purposeful selection of cases provides another methodological opportunity of future school improvement research. By analyzing the data from a school perspective, the key characteristics of the study, collaboration and teacher learning, are placed in the context of the whole school. The school perspective shows how several elements are connected to each other and how their coherence results in an organizational configuration. It is precisely the specific connection between several elements that results in different forms of teacher learning at different schools. By using contrasting cases, it becomes obvious what eventually makes the difference between schools. It is more difficult to understand what really makes the difference in studies that only focus on high-performing schools. It is the comparison between high and low performing schools on specific characteristics that makes it clear, what aspects are fundamental for differences in school capacity.

Finally, we believe that our use of digital logs is an interesting method of future longitudinal research. A long-term approach provides an additional perspective to school improvement research. The analysis of how teachers perceive the evolution of school characteristics over a longer period of time, e.g. a whole school year as in our study, provides useful insights into how schools deal with innovation, how they integrate this innovation into their internal operations, and how this leads to more or fewer effects in the professional development of their teachers. We hope that these methodological reflections can be an inspiration for future school improvement research.

References

Achinstein, B. (2002). Conflict amid community: The micropolitics of teacher collaboration. Teacher College Record, 104(3), 421–455.

Bakkenes, I., Vermunt, J. D., & Wubbels, T. (2010). Teacher learning in the context of educational innovation: Learning activities and learning outcomes of experienced teachers. Learning and Instruction, 20(6), 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.09.001

Bolam, R., McMahon, A. J., Stoll, L., Thomas, S. M., Wallace, M., Greenwood, A. M., Hawkey, K., Ingram, M., Atkinson, A., & Smith, M. C. (2005). Creating and sustaining effective professional learning communities. DfES, GTCe, NCSL. https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/RR637-2.pdf

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: Mapping the terrain. Educational Researcher, 33(8), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033008003

Bryk, A. S., Camburn, E., & Louis, K. S. (1999). Professional community in Chicago elementary schools: Facilitating factors and organizational consequences. Educational Administration Quarterly, 35(5), 751–781. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X99355004

Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 947–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7

Clement, M., & Vandenberghe, R. (2000). Teachers’ professional development: A solitary or collegial (ad)venture? Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0742-051x(99)00051-7

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational research. Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Darling-Hammond, L., Chung Wei, R., Alethea, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession: A status report on teacher development in the United States and abroad. Stanford, CA: National Staff Development Council and The School Redesign Network.

Deakin Crick, R. (2008). Pedagogy for citizenship. In F. Oser & W. Veugelers (Eds.), Getting involved: Global citizenship development and sources of moral values (pp. 31–55). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense.

Desimone, L. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Towards better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/00131189X08331140

Doppenberg, J. J., Bakx, A. W. E. A., & den Brok, P. J. (2012). Collaborative teacher learning in different primary school settings. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 18(5), 547–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2012.709731

Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26(2), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/158037042000225245

Gore, P. A. (2000). Cluster analysis. In H. E. A. Tinsley & S. D. Brown (Eds.), Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling (pp. 297–321). San Diego, CA: Academic.

Greene, J. C., Caracilli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Towards a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J., Berliner, D. C., Cochran-Smith, M., McDonald, M., & Zeichner, K. (2005). How teachers learn and develop. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world (pp. 358–389). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hargreaves, A. (1994). Changing teachers, changing times: Teachers’ work and culture in the postmodern age. London, UK: Cassell.

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four ages of professionalism and professional learning. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 6(2), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/713698714

Hipp, K. K., Huffman, J. B., Pankake, A. M., & Olivier, D. F. (2008). Sustaining professional learning communities: Case studies. Journal of Educational Change, 9(2), 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-007-9060-8

Hoekstra, A., Brekelmans, M., Beijaard, D., & Korthagen, F. (2009). Experienced teachers’ informal learning: Learning activities and changes in behavior and cognition. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 663–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.12.007

Hord, S. M. (1986). A synthesis of research on organizational collaboration. Educational Leadership, 43(5), 22–26.

Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Huberman, M. (1989). On teachers’ careers: Once over lightly, with a broad brush. International Journal of Educational Research, 13(4), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-0355(89)90033-5

Johnson, B. (2003). Teacher collaboration: Good for some, not so good for others. Educational Studies, 29(4), 337–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569032000159651

Kwakman, K. (2003). Factors affecting teachers’ participation in professional learning activities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0742-051x(02)00101-4

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2009). A typology of mixed methods research designs. Quality & Quantity, 43(2), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

Lieberman, A., & Pointer Mace, D. H. (2008). Teacher learning: The key to educational reform. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(3), 226–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108317020

Little, J. W. (1990). The persistence of privacy - autonomy and initiative in teachers professional relations. Teachers College Record, 91(4), 509–536.

Lomos, C., Hofman, R. H., & Bosker, R. J. (2011). The relationship between departments as professional communities and student achievement in secondary schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 722–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.003

Louis, K. S., Dretzke, B., & Wahlstrom, K. (2010). How does leadership affect student achievement? Results from a national US survey. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 21(3), 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.486586

Louis, K. S., & Marks, H. M. (1998). Does professional community affect the classroom? Teachers’ work and student experience in restructuring schools. American Journal of Education, 106, 532–575.

McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2001). Professional communities and the work of high school teaching (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Meirink, J. A., Imants, J., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2010). Teacher learning and collaboration in innovative teams. Cambridge Journal of Education, 40(2), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2010.481256

Meirink, J. A., Meijer, P. C., & Verloop, N. (2007). A closer look at teachers’ individual learning in collaborative settings. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 13(2), 145–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600601152496

Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. London, UK: Sage.

Newmann, F. M., Marks, H. M., Louis, K. S., Kruse, S. D., & Gamoran, A. (1996). Authentic achievement: Restructuring schools for intellectual quality. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

OECD. (2014). TALIS 2013 results: An international perspective on teaching and learning. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Putnam, R. T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029001004

Richter, D., Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2011). Professional development across the teaching career: Teachers’ uptake of formal and informal learning opportunities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.07.008

Scribner, J. S. (1999). Professional development: Untangling the influence of work context on teacher learning. Educational Administration Quarterly, 35(2), 238–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X99352004

Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. 86, 420–428. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420.

Sleegers, P., den Brok, P., Verbiest, E., Moolenaar, N. M., & Daly, A. J. (2013). Towards conceptual clarity: A multidimensional, multilevel model of professional learning communities in Dutch elementary schools. The Elementary School Journal, 114(1), 118–137. https://doi.org/10.1086/671063

Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

Svanbjörnsdóttir, B. M., Macdonald, A., & Frímannsson, G. H. (2016). Teamwork in establishing a professional learning community in a new Icelandic school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 60(1), 90–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.996595

Tam, A. C. F. (2015). The role of a professional learning community in teacher change: A perspective from beliefs and practices. Teachers and Teaching, 21(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.928122

van Veen, K., Zwart, R. C., Meirink, J. A., & Verloop, N. (2010). Professionele ontwikkeling van leraren: Een reviewstudie naar effectieve kenmerken van professionaliseringsinterventies van leraren [Teachers’ professional development: A review study on effective characteristics of professional development initiatives for teachers]. Leiden, The Netherlands: ICLON.

Vanblaere, B., & Devos, G. (2016). Exploring the link between experienced teachers’ learning outcomes and individual and professional learning community characteristics. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 27(2), 205–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1064455

Vandenberghe, R., & Kelchtermans, G. (2002). Leraren die leren om professioneel te blijven leren: Kanttekeningen over context [Teachers learning to keep learning professionally: Reflections on context]. Pedagogische Studiën, 79, 339–351.

Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.04.002

Vescio, V., Ross, D., & Adams, A. (2008). A review of research on the impact of professional learning communities on teaching practice and student learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004

Visscher, A. J., & Witziers, B. (2004). Subject departments as professional communities? British Educational Research Journal, 30(6), 786–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192042000279503

Wahlstrom, K., & Louis, K. S. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: The roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 458–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08321502

Wang, T. (2015). Contrived collegiality versus genuine collegiality: Demystifying professional learning communities in Chinese schools. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(6), 908–930. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2014.952953

Zwart, R. C., Wubbels, T., Bergen, T., & Bolhuis, S. (2009). Which characteristics of a reciprocal peer coaching context affect teacher learning as perceived by teachers and their students? Journal of Teacher Education, 60(3), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109336968

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Vanblaere, B., Devos, G. (2021). Learning in Collaboration: Exploring Processes and Outcomes. In: Oude Groote Beverborg, A., Feldhoff, T., Maag Merki, K., Radisch, F. (eds) Concept and Design Developments in School Improvement Research. Accountability and Educational Improvement. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69345-9_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69345-9_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-69344-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-69345-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)