Abstract

This article analyses the self-rated health of German emigrants and remigrants compared to non-mobile Germans. Moreover, using a scale measuring self-assessed health changes, we are able to research the health dynamics immediately before and after the migration event. Data from the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS) as well as from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) that covers the general German population are used. In researching how self-selectivity of German migrants contributes to health differences, we use linear regression models to control for a series of relevant covariates. Our findings show a healthy migrant effect for German emigrants and remigrants compared to the German general population. This advantage diminishes after controlling for the covariates, but remains relevant in size and significance. Moreover, the health advantage increases with age at the time of migration. Furthermore, we find only weak evidence that migration has a negative effect on health. The analyses rather show that more than 50% of the migrants report that their health is the same as before the migration, around 30% report health improvements, and only a minor group report worsening health.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Migration studies are generally focused on the economic implications of international migration, for example for national labour markets (e.g. “brain drain”) or for individual occupational careers (Ette and Witte 2021; Witte and Guedes Auditor 2021). In addition to this perspective, more and more research is being conducted that gives insights into the non-economic consequences of migration, for instance for family lives (Baykara-Krumme et al. 2021) or life satisfaction (Hendricks 2015; Guedes Auditor and Erlinghagen 2021 in this volume). This chapter contributes to this second strand of research by investigating self-rated health, which refers to the physical and mental health situation of individuals (e.g. Simon et al. 2005), and measures aspects of their present quality of life. However, health is not only a consequence of international migration, but also a factor that may influence whether and possibly also why individuals move (e.g. van Dalen and Henkens 2013).

A close link between international migration and health has already been established. The so-called “healthy migrant paradox” states that migrants often show better health (e.g. in terms of self-rated health, mortality, Body Mass Index) compared to native-born individuals, also after controlling for socio-economic characteristics. This paradox has been established in investigations mainly focusing on persons that migrate from low-income to high-income countries (Fennelly 2007; Lu and Zhang 2016). Generally, it is explained by selective immigration or return migration (e.g. Constant 2017), with the former regularly being discussed as the more important factor (Jasso et al. 2004; Kennedy et al. 2015). While it is often assumed that better health at the time of migration can be ascertained for immigrants in the USA, Canada and Australia, the results for Europe are more heterogeneous (Huijts and Kraaykamp 2012; Markides and Rote 2019; Nielsen and Krasnik 2010). A closer look at the literature, however, reveals that this may depend on the origin and destination context as well as on migration motives (e.g. flight and displacement vs. economic reasons) (McKay et al. 2003; Rechel et al. 2013). Therefore, for certain groups of migrants some studies show no health advantages or even poorer health compared to the population in the receiving country (e.g. Constant et al. 2018; Jatrana et al. 2018). Furthermore, initial health advantages disappear over time, for example due to adopting a less healthy lifestyle (e.g. nutrition, less physical exercise) in the most developed countries, bad working conditions, discrimination, cultural differences, language barriers, and loss of social networks (Ahonen et al. 2007; Lassetter and Callister 2009; Lubbers and Gijsberts 2019). However, there are also studies reporting possible long-term health improvements by adopting a healthier life style (Hedlund et al. 2007; Guo et al. 2014) and short-term increases in self-rated health directly after the migration (Erlinghagen et al. 2009; Jasso et al. 2004).

Existing investigations studying the health status of migrants predominantly focus on migration from low-income countries, whereas analyses focusing on high-income countries are largely lacking in the literature. Studies dealing with this topic show that immigrants from Europe, the USA, Canada, the UK, and Australia report better health than people born in the destination or origin population (Huang et al. 2011; Kennedy et al. 2015), but immigrants from high-income countries living in Sweden report poorer health compared to Swedes (Lindström et al. 2001). Moreover, German emigrants and remigrants report better self-rated health than people permanently living in Germany and health seems to improve after migration (Erlinghagen 2011; Erlinghagen and Stegmann 2009; Engler et al. 2015). Finally, studies focusing on migration intentions of Europeans show no effect of health on short-term emigration intentions (migration within 1 year or the near future) but on long-term (within the next 5 years) intentions (van Dalen and Henkens 2007; Williams et al. 2017). Additionally, those emigrants with better health are more likely to translate their intention into actual migration behaviour (van Dalen and Henkens 2013).

This study investigates the self-rated health of German emigrants and remigrants using the first wave of the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS). First, these data enable the investigation of self-rated health in the context of an economically highly developed country. Second, the vast majority of existing studies compare migrants with the population in the destination country, regularly resulting in several methodological shortcomings. In line with the overall conceptual framework of the GERPS study (see Erlinghagen et al. 2021 on the DOM-approach), this paper compares self-rated health of migrants with that of the origin population. It combines the GERPS sample with data of the general (non-migrant) population living in Germany from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) and highlights one of the theoretical and methodological advantages of this new data infrastructure. Third, because the interviews took place shortly after emigration, potential bias on the average self-rated health of emigrants due to selective return migration to Germany is minimised. Fourth, little is known about the immediate effects of a migration event on health. By using a measure for the self-assessed changes in the health (present situation vs. situation before migration), we are also able to shed some light on this issue.

The following section deals with the theoretical background and Sect. 3 describes the data and methods. The empirical results are presented in Sect. 4. The chapter concludes with a summary and discussion of the central findings.

2 Theoretical Background

The healthy migrant effect generally refers to better health of migrants (e.g. Constant 2017; Lu and Zhang 2016). This is paradoxically also true for migrants from low-income countries who usually have lower socio-economic status than the population in the destination country. Indeed, there are at least two groups for comparisons with migrants: persons in the sending and in the receiving society, while the comparison with those living in the receiving country is the most common in the literature. In this paper, we compare German emigrants and remigrants with internationally non-mobile people living in Germany. Comparing migrants with non-migrants from the country of origin has the advantage that potential biases due to the differences in the average health level between the sending and receiving country can be excluded. Additionally, analysing the selectivity of migrants in this group is a more appropriate counterfactual (Kennedy et al. 2015; Razum 2009). Furthermore, we have to consider several mechanisms that contribute to the health of migrants: selection of those who emigrate and those who remigrate, effects of the migration event, and changes in health during the stay in the receiving country (Jasso 2013; Lu and Zhang 2016).

In our theoretical considerations we focus on two distinct groups (emigrants and remigrants) and address the underlying mechanisms that possibly lead to differences in self-rated health compared with Germans living in Germany.

2.1 German Emigrants

We first focus on the decision to emigrate, which is mostly driven by the motive to improve an existing (possibly dissatisfying) situation, for example due to job or family-related reasons, the desire to experience something new, or to increase the quality of life in general (Engler et al. 2015; Tabor et al. 2015; van Dalen and Henkens 2007). Migration, however, can involve complex decisions. It can be a lengthy process with different phases and negotiations with the partner and the family in which information about the requirements for the move and the destination country are gathered (De Jong 2000; Mincer 1978; Stark and Bloom 1985; Tabor et al. 2015). Despite this complex decision-making process the decision to move may be driven by the fact that subjectively perceived benefits of the move are greater than the costs–including monetary (e.g. income) as well as non-monetary (e.g. quality of life, health care, or social contacts) costs and benefits (Sjaastad 1962; Hoppe and Fujishiro 2015). If migration is mainly motivated by economic reasons (income, career opportunities), we can assume that young and highly educated individuals in particular migrate because the benefits of migration as well as the time in which the investment pays off is greater for these groups (Ette and Sauer 2010; Niefert et al. 2001; Uebelmesser 2006). Bringing health into this equation, Jasso et al. (2004) argue that health is positively related to income, because health increases one’s individual skill level and skill utilisation as stated in the human capital theory (Grossman 1972). Since human capital and health are positive correlated, this consequently leads to a selection of healthy labour migrants. From another perspective, the decision to migrate itself can be challenging because it binds resources, for example to search for information, to prepare the move, or for the negotiation process with partner and family. Thus personal traits like self-efficacy, which influence how individuals cope with situations, may play an important role (Hoppe and Fujishiro 2015; van Dalen and Henkens 2007). Moreover, the study by van Dalen and Henkens (2013) shows that healthier persons are more likely to transform their migration intentions into migration behaviour.

Against this background, the study by Kennedy et al. (2015) on emigrants from the USA, the UK, Canada, and Australia reveals positive health selection compared to the non-mobile counterparts living in the country of origin. Since German emigrants are positively selected regarding age and educational level (Ette and Sauer 2010; Erlinghagen and Stegmann 2009), the studies by Engler et al. (2015) and (Erlinghagen 2011) show better self-rated health of German migrants. This argumentation leads to the following hypothesis:

H1.1

German emigrants have better self-rated health compared to internationally non-mobile Germans.

Furthermore, age and health are negatively correlated (e.g. House et al. 1990). However, little is known about potential variations in the health selectivity of emigrants by age. Lu and Zhang (2016, p. 23) argue that older migrants are negatively selected on health because they emigrate to find better health care or to move closer to relatives who can take care of them.Footnote 1 However, since the quality of the German health care system is relatively high (Reibling et al. 2019) it is more appropriate to assume that individuals with poor health or health problems stay in Germany.Footnote 2 In keeping with this, the analysis by Hall (2016) suggests that retirement emigrants coming from the UK and living in Spain are fit and healthy. In sum, the selection effect might become stronger for older migrants because those who need medical assistance stay in Germany. This leads us to the next hypothesis:

H1.2

The health advantage of German emigrants compared with their non-migrant counterparts living in Germany becomes stronger with increasing age at migration.

If individuals decide to move, they are faced with impacts of the migration event itself and with the situation of living in another country. Migration is a challenging, major life event (Constant 2017; Friis et al. 1998) that often means visa stress, living separated from partner, family, and friends. It can also lead to unforeseen psychological and monetary costs. Therefore, we can assume that such burdens may lead to mental health issues (e.g. homesickness, loneliness, depression). Moreover, with increasing time after migration language barriers, cultural distance, discrimination, lack of social and emotional support, discrepancies of expectations and success, adopting an unhealthier lifestyle, or limited health care can reduce migrants’ health (Bhugra and Becker 2005; Delavari et al. 2013; Huijts and Kraaykamp 2012). Having social contacts in the destination country can mitigate negative effects (Finch and Vega 2003; Lubbers and Gijsberts 2019). In contrast, migration may also lead to health improvements due to higher quality of life and standard of living (e.g. income increases) (Lu and Zhang 2016). Against this background, existing studies often show long-term (over about 10 years) and slow reduction of the initial health advantage of migrants (Constant 2017; Lassetter and Callister 2009).

Furthermore, investigations that focus on short-term changes in health (after 1 year since migration) find that self-rated health in the year after migration increases (Erlinghagen et al. 2009; Jasso et al. 2004). This short-term health improvement may also be a return effect to the “normal” health level before migration, which was reduced because of the dissatisfying situation before migration as well as being exposed to different stressors during the decision-making process and the migration event.Footnote 3 Furthermore, personal traits that help to cope with the stressors in the migration situation may be another reason why the comparatively negative impact of the migration event is weak over a short period (Bhugra 2004; Kuo and Tsai 1986; van Dalen and Henkens 2007). German emigrants are also positively selected in their personal traits and happier than their German counterparts living in Germany (Engler et al. 2015; Erlinghagen 2011). Taken together, we can assume the following:

H2

German emigrants report mainly stable or slightly increasing health directly after migration.

2.2 German Remigrants

In migration research comparatively little is known about return migration (Salaff 2013). This makes it challenging to make assumptions about returnees’ health. Largely in line with economic hypotheses about the intensifying effect of return migration on the original self-selection of emigrants (Borjas and Bratsberg 1996), the so-called Salmon bias is a well-established assumption in the context of migration and health. It explains the healthy migrant paradox by referring to selective return migration of (relatively) ill immigrants to their home countries (Constant 2017). Evidence for negative selection is found, for example, for Turkish migrants remigrating from Germany and for Mexicans remigrating from the USA (Razum et al. 1998; Arenas et al. 2015). Additionally, as Ette and Sauer (2010) show, the age profile of German return migrants and emigrants largely matches, but there is a non-negligible group returning at retirement age. Therefore, we assume that a share of the return migrants may move because of their worsening health. However, that does not lead directly to the conclusion that remigrants have poorer health compared to people living in their country of origin. Return migrants may even have better health and move back to their home country due to (minor) health changes that need medical assistance (Hall 2016).

Beyond this, if emigration motives that are important for the remigration intention and decision are taken into account (Salaff 2013; Steiner 2019), we see that international students and highly educated individuals from Germany have an increased rate of remigration to their country of origin (Ette and Sauer 2010). Moreover, in the context of the human capital theory (Becker 1975) we can argue that studying as well as working abroad is an investment in human capital. Since the investment needs to pay off on the national labour market in the long run (Waibel et al. 2017), we can assume that those groups of return migrants are relatively young. Since–as argued above–education is positively correlated with health, another share of return migrants should show good health. Against this background and as tentative results from Engler et al. (2015) and Erlinghagen (2011) suggest, German remigrants have better health compared to non-migrants living in Germany, but their health compared to German emigrants is poorer.

H3

German remigrants have better self-rated health than non-mobile Germans, but poorer health than German emigrants.

In the following, we focus on health changes among remigrants around the time of the migration event. For those who migrate because of their need for medical care, we can assume health improvements or at least not further declining health if they are treated. On the contrary, there might be further health decline (reported) when more ailments are diagnosed (Steiner 2019). Further important motives for return migrants are to be closer to relatives and friends or being dissatisfied with their life abroad (Engler et al. 2015; Steiner 2019). The strains of living separately from close social contacts should disappear for those who remigrate and, consequently, health should improve. On the other hand, the decision to remigrate, the migration event itself (see above) as well as (short-term) re-adjustment problems after returning to the country of origin (e.g. Szkudlarek 2010) could lead to strains. However, since the most important reason to remigrate is social contacts, health improvements would make more sense. This leads us to the final hypothesis:

H4

German remigrants report mainly stable or slightly improving health directly after migration.

3 Data and Methods

The following analyses use data from the first wave of the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS) and the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) to compare emigrants and remigrants with non-mobile Germans (see Ette et al. 2021).Footnote 4 The samples are restricted to respondents aged between 20 and 70 due to the sample frame of the GERPS data.

Using GERPS and SOEP, we are able to differentiate three distinct groups that are important for the following analyses: emigrants, remigrants, and non-migrants. Emigrants refer to German citizens who deregistered from Germany between July 2017 and June 2018 stating that they moved abroad. In turn, remigrants registered in Germany during the same period stating that they previously lived abroad. The data were collected between November 2018 and February 2019. At this time, on average the emigrants had been abroad for 12.6 months and the remigrants returned on average 11.6 months previous.Footnote 5 The sub-sample of non-migrants was drawn from German citizens who were interviewed in 2017 in the context of the SOEP (irrespective of any stays abroad throughout their biography).

As dependent variable we employ the self-rated health of the respondents and the subjectively assessed changes in the health status. Self-rated health is a well-established single-item scale to measure the general health of a person. Studies show that self-rated health is a good predictor for mortality among adults (e.g. Burström and Fredlund 2001), it correlates with objective health (Wu et al. 2013), and captures both physical as well as mental health (Simon et al. 2005). In the GERPS and SOEP questionnaires the respondents were asked to rate their current health from 0, very good, 1, good, 2, satisfactory, 3, poor to 4, bad. For the analysis, we turned high into low values, and vice versa.

The second item focuses on self-assessed short-term changes in health during the context of international migration. To measure this, the respondents were asked on a single-item scale to compare their current personal health situation with that before they migrated on a scale reaching from 1, much better, 2, better, 3, about the same, 4, worse to 5, much worse. For the analysis, we recoded the item so that it ranges from −2, worse to 2, much better. Even though there is no direct measurement of health at the time before migration, the item offers the opportunity to study the dynamics of health around the time of the migration event.

As covariates, we include sex and age of the respondent. Regarding age, we use polynomials up to the fourth degree to represent non-linear relationships of age and health. Moreover, we consider the migration background, which measures whether a person is born abroad and migrated to Germany during his or her biography but holds German citizenship when the sample was drawn. Furthermore, we control for the socio-economic status of a person using the years of education. Additionally, we consider the present labour force status of the respondents, differentiating between employed, self-employed, unemployed, retired, not employed, and presently enrolled in education. We also take into account whether a migrant is an expatriate or not, based on the question: “Have you been sent by your employer?” We also account for the personality of the respondents considering the locus of control (internal and external) (Rotter 1966), which strongly correlates with other personal traits like self-efficacy or self-esteem (Judge et al. 2002). To operationalise how people believe that they can determine their own life course, we use four of the seven original items from Specht et al. (2013) (Kovaleva et al. 2012). The respondents were asked to rate on a 7-point scale (from 1, not at all to 7, absolutely) to what degree they personally agree with the following statements: “How my life goes depends on me.”, “One has to work hard in order to succeed.”, “I frequently have the experience that other people have a controlling influence over my life.”, and “What a person achieves in life is above all a question of fate or luck.” The first two items refer to internal locus of control, the latter two measure the external dimension. Finally, to account for the general level of development of recent (emigrants) and former (remigrants) host countries, which may explain variation in changes in self-rated health of the migrants, we use the human development index (HDI) (UNDP 2019).

In our analysis, we first investigate the health differences between our analytical groups (emigrants, remigrants, non-migrants) using descriptive statistics and linear regression models. To research how the self-selection of emigrants and remigrants contributes to the health differences, we control for demographic, socio-economic and psychological characteristics in the linear regression models. The dependent variable self-rated health can also be regarded as an ordinal response, therefore we performed robustness checks by employing ordered logit models (Long 2015), with similar results. In a second step, we analyse the self-assessed changes in health around the time of the migration event using ordered logit models.

4 Results

4.1 Current Health Status

Table 12.1 contains the means of all variables differentiated by our three analytical groups: emigrants, remigrants, and non-migrants. The results show that German emigrants and remigrants on average report better self-rated health, which is around 0.8 and 0.7 points better than that of non-migrants, respectively. In Fig. 12.1, the distribution of self-rated health is shown for each group. One can see that 41.4% of the emigrants and 36.1% of the remigrants rate their health as very good, while only 9.6% of non-mobile Germans do. Instead, non-migrants state much more often that their health is satisfactory, while this is true for only 14–15% of the migrants. The other categories are more similar distributed, but a higher percentage of the non-migrants (2.9%) state that their health is bad, in contrast to 0.4% of emigrants and 1.0% of the remigrants. Furthermore, Table 12.1 reveals that our samples consist to equal parts of women and men. Moreover, emigrants and remigrants have a migration background slightly more often and are around 10 years younger than non-migrants. German migrants show higher educational levels than non-migrants. Regarding labour force status, emigrants are less often unemployed or retired, but more often enrolled in education or not employed than non-migrants. For the remigrants we find that a lower percentage is employed or retired compared to non-migrants, while there is a higher share of unemployed, not employed, or persons in education. Furthermore, migrants and non-migrants express similar values regarding their internal locus of control. However, emigrants and remigrants feel that their life is controlled by external factors less often than non-mobile Germans.

In the next step, we conduct regression analyses to check the selectivity of demographic, socio-economic and psychological characteristics. Figure 12.2 shows the changes of the estimated health differences between migrants and non-migrants, when controlling for sets of covariates. Figure 12.3 shows the coefficients and standard errors of the full model (all values can be found in Table 12.2 in the appendix). Figure 12.2, model 1 shows that, on average, emigrants (B = 0.79, SE = 0.017, p ≤ 0.001) and remigrants (B = 0.67, SE = 0.014, p ≤ 0.001) rate their health significantly better than non-migrants. The migration status variable explains around 13% of the variance in health. From model 2 (Fig. 12.2), we can see that the effect diminishes when the sex of the respondent, age, and migration background are controlled. A more detailed analysis reveals that the health difference is reduced due to controlling for age differences (migrants are on average younger). In model 3 (Fig. 12.2), the educational level and the labour force status are additionally controlled. Here, detailed analysis reveals that emigrants and remigrants have greater values in self-rated health because they have higher educational levels. Additionally considering the psychological characteristics of the respondents in model 4 (Fig. 12.2) again diminishes the estimated health differences. The reason for this is that migrants have lower values for external locus of control. In sum, the health advantage of German emigrants and remigrants compared to non-migrants reduces by more than 50%, when demographic, socio-economic and psychological characteristics are controlled. However, it remains a health advantage for emigrants (B = 0.44, SE = 0.018, p ≤ 0.001) and remigrants (B = 0.38, SE = 0.016, p ≤ 0.001) that is relevant in size and significance (model 4, Figs. 12.2 and 12.3; Table 12.2).

Changes in the estimated health differences between emigrants, remigrants and non-migrants (ref. non-migrants). (Sources: GERPSw1, SOEP2017, N = 24,022, authors’ calculations). Notes: Model 1: migration status; Model 2: as model 1 + sex, age and migration background; Model 3: as model 2 + education and labour force status. Model 4: as model 3 + internal and external locus of control

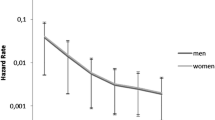

As mentioned, Fig. 12.3 displays the results from the full linear regression model for all covariates, which are mainly in line with the literature on self-rated health and not discussed in detail here. For example, a higher educational level increases self-rated health as well as higher values of internal locus of control. Increased values of external locus of control reduce self-rated health (Furnée et al. 2008; Mackenbach et al. 2002). However, how the health advantage of migrants compared to non-migrants varies with age is of special interest. Figure 12.4 shows the estimated means of self-rated health over age for the three analysed groups from a model that controls for migration status and four polynomials of age as well as interaction effects between both. For emigrants (Fig. 12.4a) these estimates show that self-rated health is around 0.3 points higher at the age of 20 compared to non-migrants. This health advantage peaks at the ages 50 and 60 where self-rated health is around 0.7 points higher. After the age of 60, differences become smaller. Note that the health difference is not significant at an age of 70, which may be a result of the small number of cases. Moreover, for remigrants (Fig. 12.4b) we find that the health advantage compared to non-migrants becomes greater over age continuously. The difference at age 20 is 0.2 and this advantage increases until the ages 60 and 70 to 0.7 and 0.8 points respectively.

4.2 Short-Term Changes in Health Around the Time of the Migration Event

Figure 12.5 shows the distribution of the self-assessed health changes around the time of the migration event. The vast majority of emigrants and remigrants report that their health is about the same as before migration. Interestingly, 34.3% of the emigrants and 29.7% of remigrants report health improvements compared to the situation before. However, remigrants (14.1%) report health declines more often than emigrants (8.8%). We conducted ordered logistic regression models to research the self-assessed health changes in detail (see Table 12.3 in the appendix). These models show that socio-demographic characteristics do not explain the reported health changes. The time since emigration or remigration also does not explain the self-assessed health changes. However, for remigrants with migration backgrounds, we find higher odds (B = 1.37, SE = 0.104, p ≤ 0.001) for reporting a health improvement compared to persons without a migration background. Furthermore, self-employed (B = 1.90, SE = 0.252, p ≤ 0.001) and retired (B = 2.16, SE = 0.581, p = 0.004) emigrants report improved health while expatriates (B = 0.51, SE = 0.064, p ≤ 0.001) are more likely to exhibit declining health. Psychological characteristics are also relevant for explaining health changes. Emigrants with higher values of internal locus of control show a higher probability (B = 1.10, SE = 0.041, p = 0.009) of reporting improved health, while those with greater external locus of control are more likely to report declines in health (B = 0.93, SE = 0.031, p = 0.041). Moreover, the destination country also seems to play an important role. Emigrants in countries with a higher human development index (HDI) are more likely to report increased health (B = 1.02, SE = 0.005, p = 0.001), while remigrants from countries with higher HDI have higher odds to report diminished health (B = 0.98, SE = 0.002, p ≤ 0.001), which also means that remigrants from countries with lower HDI report health increases.

5 Conclusion and Discussion

This study aimed to research the self-rated health and the self-assessed health changes of German emigrants and remigrants. For this, we used the first wave of the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS). Deploying this data enables us to address questions about the so-called healthy migrant effect in the context of migration from a high-income country, a topic that is largely absent from the literature (Markides and Rote 2019). Since interviews took place shortly after the migration event, the effect of selective return migration of ill persons (Salmon effect) is minimised and is not expected to bias the results. Additionally, the health of the individuals returning to Germany is also investigated. Moreover, by using the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) as sub-sample, we were able to compare German migrants with non-migrants in the origin country, which are more appropriate counterfactuals as the destination population (Jasso et al. 2004; Razum 2009). Finally, using an item that measures self-assessed health changes around the time of the migration event (comparison of the present situation with that before the migration) allows us to shed some light on the health dynamics during the international migration, a topic on which almost nothing is known.

Corresponding with our expectations, we find a healthy migrant effect for German emigrants (H1.1) and remigrants (H3) compared to non-migrants living in Germany. These findings are in line with other studies focusing on German migrants (Engler et al. 2015; Erlinghagen 2011). The analysis revealed that the health advantage of German migrants in contrast to non-migrants can be partly explained by their younger age, their higher education and their lower values of external locus of control. Therefore, as theoretically expected, the self-selectivity of German migrants partly accounts for their better self-rated health (Ette and Sauer 2010; Erlinghagen et al. 2009; Jasso et al. 2004). Interestingly, a considerable health advantage remains after controlling for relevant covariates. A reason for this might be that relevant factors were not observed or because health slightly increases around the time of the migration event. However, as the results of van Dalen and Henkens (2013) suggest, health seems to be important in terms of translating migration intentions into behaviour. Therefore, ceteris paribus, better health can make migration more likely.

Furthermore, our results show that the health advantage of emigrants and remigrants do not disappear with age (H1.2) as Lu and Zhang (2016) assume. In contrast, while the relationship for emigrants seems to be an inverted parabolic (the advantage first increases and then decreases), for remigrants a continuous increase in the health advantage can be found. This may be due to Germans being less likely to move to other countries to search for better health care because the quality of the German health system is already relatively high (Reibling et al. 2019). For the remigrants, we can assume that they initially are positively selected with regard to their health, but may move back to Germany in the case of (minor) declines in health (Hall 2016). Moreover, emigrants of younger ages have better self-rated health compared to remigrants, which supports the idea that a negatively selected group of migrants returns to their country of origin (Borjas and Bratsberg 1996). However, at higher ages remigrants tend to report greater values of self-rated health compared to emigrants.

The analyses of the health dynamics around the time of the migration event provide only weak evidence of a negative effect of migration on health. The analyses instead reveal that more than 50% report that their health did not change, while around 30% report health improvements. This result is in line with our theoretical expectations (H2 and H4) and existing findings (Erlinghagen et al. 2009; Jasso et al. 2004). Notably, expatriates are more likely to report declines in health after emigration. This finding is consistent with the literature documenting adjustment problems, especially in the period shortly after arrival, and poorer health in specific aspects (e.g. infectious diseases) among expatriates (Anderzén and Arnetz 1999; Foyle et al. 1998; Patel 2011). Moreover, the general level of development of the (former) destination country as well as personal traits also play a role in explaining health changes around migration (Bhugra 2004; McKay et al. 2003; van Dalen and Henkens 2007).

Several limitations of the study should be addressed here. First, our results should be interpreted carefully in terms of causality as all analyses are cross-sectional. Second, in the first wave of GERPS only the global self-rated health is available as measure of current health. However, as mentioned in our theoretical section and suggested by research on internal migration (Lu 2010; Nauman et al. 2015), migration may have different effects on mental and physical health. Third, we can only research short-term changes in global health using self-assessed retrospective ratings. In future research it would be interesting to see how self-rated health changes in the long-term, for example is there further improvement due to fitting in over time or does health decline after a brief “happiness effect”. Fourth, our results suggest that the health advantage of emigrants and remigrants varies with the destination context. Therefore, it may be fruitful to research this in more detail, for example by considering the spatial and cultural distance. Finally, future studies should examine if the health advantage of migrants differs with regard to different life course statuses and transitions.

Altogether, this study expands the existing literature by researching the health of emigrants and remigrants from a high-income country by comparing it with the health of the origin population. We also provide insights with regard to health changes around the time of the migration event. Furthermore, we demonstrated the possibilities of researching health in the context of international migration using the German Emigration and Remigration Panel Study (GERPS). Future investigations deploying this data will be able to research health changes of emigrants and remigrants prospectively over a period of at least 2 years (four panel waves). Moreover, it will be possible to differentiate between physical and mental health to shed even more light on the relationship between international migration and health.

Notes

- 1.

The results of van Diepen and Mulder (2009) for older Dutch internal migrants do not suggest that they move closer to relatives because of health problems.

- 2.

The results of Sander (2007) suggest such an effect for immigrants living in Germany.

- 3.

Evidence that this may be the case comes from two studies dealing with rural-to-urban migration, which show a positive selection of migrants regarding their physical health, but poorer mental health compared to those who stayed (Lu 2010; Nauman et al. 2015). Additionally, while there is almost no effect of migration on physical health, migrants show improvements in mental health over a period of three years up and above the level of rural non-migrants and remigrants.

- 4.

Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), v34, SOEP, 2019, doi: https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.v34

- 5.

Population registers are administrative data sources that do not perfectly match the actual life courses of the registered population. Therefore, GERPS also includes emigrants with substantially longer stays abroad as well as remigrants who returned before July 2017. For a more detailed discussion of this issue, see Chap. 2 in this volume. Because the time elapsed since the migration event potentially influences subjective health, we only consider those cases whose emigration or remigration took place at most 36 months before the date of the interview.

References

Ahonen, E. Q., Benavides, F. G., & Benach, J. (2007). Immigrant populations, work and health—a systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 33(2), 96–104.

Anderzén, I., & Arnetz, B. B. (1999). Psychophysiological reactions to international adjustment. Results from a controlled, longitudinal study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 68(2), 67–75.

Arenas, E., Goldman, N., Pebley, A. R., & Teruel, G. (2015). Return migration to mexico: Does health matter? Demography, 52(6), 1853–1868.

Baykara-Krumme, H., Erlinghagen, M., & Mansfeld, L. (2021). Disruption of family lives in the course of migration: ’Tied migrants’ and partnership breakup patterns among German (r)emigrants. In M. Erlinghagen, A. Ette, N. F. Schneider, & N. Witte (Eds.), The global lives of German migrants. Consequences of international migration across the life course. Cham: Springer.

Becker, G. S. (1975). Human capital. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bhugra, D. (2004). Migration and mental health. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109(4), 243–258.

Bhugra, D., & Becker, M. A. (2005). Migration, cultural bereavement and cultural identity. World Psychiatry, 4(1), 18–24.

Borjas, G. J., & Bratsberg, B. (1996). Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 78(1), 165–176.

Burström, B., & Fredlund, P. (2001). Self rated health: Is it as good a predictor of subsequent mortality among adults in lower as well as in higher social classes? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55, 836–840.

Constant, A. F. (2017). The healthy immigrant paradox and health convergence. ifo DICE Report, 15(3), 20–25.

Constant, A. F., García-Muñoz, T., Neuman, S., & Neuman, T. (2018). A "healthy immigrant effect" or a "sick immigrant effect"? Selection and policies matter. The European Journal of Health Economics, 19(1), 103–121.

De Jong, G. F. (2000). Expectations, gender, and norms in migration decision-making. Population Studies, 54(3), 307–319.

Delavari, M., Sønderlund, A. L., Swinburn, B., Mellor, D., & Renzaho, A. (2013). Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries—a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13, 458.

Engler, M., Erlinghagen, M., Ette, A., Sauer, L., Scheller, F., Schneider, J., & Schultz, C. (2015). International Mobil: Motive, Rahmenbedingungen und Folgen der Aus-und Rückwanderung deutscher Staatsbürger. Berlin

Erlinghagen, M., and Stegmann, T. (2009). Goodbye Germany – und dann? SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 193.

Erlinghagen, M. (2011). Kein schöner Land? Glück und Zufriedenheit deutscher Aus- und Rückwanderer. Comparative Population Studies—Zeitschrift für Bevölkerungswissenschaft, 36(4), 869–898.

Erlinghagen, M., Ette, A., Schneider, N. F., & Witte, N. (2021). Between origin and destination: German migrants and the individual consequences of their global lives. In M. Erlinghagen, A. Ette, N. F. Schneider, & N. Witte (Eds.), The global lives of German migrants. Consequences of international migration across the life course. Cham: Springer.

Erlinghagen, M., Stegmann, T., & Wagner, G. G. (2009). Deutschland ein Auswanderungsland? DIW Wochenbericht, 39(2009), 663–669.

Ette, A., Décieux, J. P., Erlinghagen, M., Auditor, J. G., Sander, N., Schneider, N. F., & Witte, N. (2021). Surveying across borders: The experiences of the German emigration and remigration panel study. In M. Erlinghagen, A. Ette, N. F. Schneider, & N. Witte (Eds.), The global lives of German migrants. Consequences of international migration across the life course. Cham: Springer.

Ette, A., & Sauer, L. (2010). Auswanderung aus Deutschland. Daten und Analysen zur internationalen Migration deutscher Staatsbürger. Wiesbaden: VS.

Ette, A., & Witte, N. (2021). Brain drain or brain circulation? Economic and non-economic factors driving the international migration of German citizens. In M. Erlinghagen, A. Ette, N. F. Schneider, & N. Witte (Eds.), The global lives of German migrants. Consequences of international migration across the life course. Cham: Springer.

Fennelly, K. (2007). The Healthy Migrant Phenomenon. In P. F. Walker & E. D. Barnett (Eds.), Immigrant medicine: A comprehensive reference for the care of refugees and immigrants (pp. 19–26). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier.

Finch, B. K., & Vega, W. A. (2003). Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health, 5(3), 109–117.

Foyle, M. F., Dominic Beer, M., & Watson, J. P. (1998). Expatriate mental health. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 97(4), 278–283.

Friis, R., Yngve, A., & Persson, V. (1998). Review of social epidemiologic research on migrants’ health: findings, methodological cautions, and theoretical perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine, 26(3), 173–180.

Furnée, C. A., Groot, W., & Brink, H. v. d. M. (2008). The health effects of education: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Public Health, 18(4), 417–421.

Grossman, M. (1972). The demand for health—A theoretical and empirical investigation. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Guedes Auditor, J., & Erlinghagen, M. (2021). The happy migrant? Emigration and its impact on social wellbeing. In M. Erlinghagen, A. Ette, N. F. Schneider, & N. Witte (Eds.), The global lives of german migrants. Consequences of international migration across the life course. Cham: Springer.

Guo, S., Lucas, R. M., Joshy, G., & Banks, E. (2014). Cardiovascular disease risk factor profiles of 263,356 Older Australians according to region of birth and acculturation, with a focus on migrants born in Asia. PLoS One, 10(2), e0115627.

Hall, K. (2016). Retirement migration and health: growing old in Spain. In F. Thomas (Ed.), Handbook of migration and health (pp. 402–418). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hedlund, E., Kaprio, J., Lange, A., Koskenvuo, M., Jartti, L., Rönnemaa, T., & Hammer, N. (2007). Migration and coronary heart disease: A study of Finnish twins living in Sweden and their co-twins residing in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 35(5), 468–474.

Hendricks, M. (2015). The happiness of international migrants: A review of research findings. Migration Studies, 3(3), 343–369.

Hoppe, A., & Fujishiro, K. (2015). Anticipated job benefits, career aspiration, and generalized self-efficacy as predictors for migration decision-making. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 47, 13–27.

House, J. S., Kessler, R. C., Regula Herzog, A., Mero, R. P., Kinney, A. M., & Breslow, M. J. (1990). Age, socioeconomic status, and health. The Milbank Memorial Fund, 68(3), 383–411.

Huang, C., Mehta, N. K., Elo, I. T., Cunningham, S. A., Stephenson, R., Williamson, D. F., & Venkat Narayan, K. M. (2011). Region of birth and disability among recent U.S. immigrants: Evidence from the 2000 census. Population Research and Policy Review, 30(3), 399–417.

Huijts, T., & Kraaykamp, G. (2012). Immigrants’ health in Europe: A cross-classified multilevel approach to examine origin country, destination country, and community effects. International Migration Review, 46(1), 101–137.

Jasso, G. (2013). Migration and health. In S. J. Gold & S. J. Nawyn (Eds.), The routledge international handbook of migration studies (pp. 366–379). Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge.

Jasso, G., Massey, D. S., Rosenzweig, M. R., & Smith, J. P. (2004). Immigrant health: Selectivity and acculturation. In N. B. Anderson, R. A. Bulatao, & B. Cohen (Eds.), Critical perspectives on racial and ethnic differences in health in late life (pp. 227–266). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Jatrana, S., Richardson, K., & Pasupuleti, S. S. R. (2018). Investigating the dynamics of migration and health in Australia: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Population, 34(4), 519–565.

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 693–710.

Kennedy, S., Kidd, M. P., McDonald, J. T., & Biddle, N. (2015). The healthy immigrant effect: Patterns and evidence from four countries. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 16(2), 317–332.

Kovaleva, A., Beierlein, C., Kemper, C. J., and Rammstedt, B. (2012). Eine Kurzskala zur Messung von Kontrollüberzeugung: Die Skala Internale-Externale- Kontrollüberzeugung-4 (IE-4). GESIS-Working Papers (19).

Kuo, W. H., & Tsai, Y.-M. (1986). Social networking, hardiness and immigrant’s mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 27(2), 133–149.

Lassetter, J. H., & Callister, L. C. (2009). The impact of migration on the health of voluntary migrants in Western Societies. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20(1), 93–104.

Lindström, M., Sundquist, J., & Östergren, P. O. (2001). Ethnic differences in self reported health in Malmö in southern Sweden. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 55, 97–103.

Long, S. J. (2015). Regression Models for Nominal and Ordinal Outcomes. In W. Henning Best & Christof (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of regression analysis and causal inference (pp. 173–204). Los Angeles: Sage.

Lu, Y. (2010). Rural-urban migration and health: Evidence from longitudinal data in Indonesia. Social Science & Medicine, 70(3), 412–419.

Lu, Y., & Zhang, A. T. (2016). The link between migration and health. In F. Thomas (Ed.), Handbook of migration and health (pp. 19–43). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Lubbers, M., & Gijsberts, M. (2019). Changes in self-rated health right after immigration: A panel study of economic, social, cultural, and emotional explanations of self-rated health among immigrants in the Netherlands. Frontiers in Sociology, 4.

Mackenbach, J. P., Simon, J. G., Looman, C. W. N., & Joung, I. M. A. (2002). Self-assessed health and mortality: could psychosocial factors explain the association? International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(6), 1162–1168.

Markides, K. S., & Rote, S. (2019). The healthy immigrant effect and aging in the United States and other Western Countries. Gerontologist, 59(2), 205–214.

McKay, L., Macintryre, S., & Ellaway, A. (2003). Migration and health: A review of the international literature. Occasional Paper. 12. MRC Social & Public Health Sciences Unit.

Mincer, J. (1978). Family migration decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 86(5), 749–773.

Nauman, E., VanLandingham, M., Anglewicz, P., Patthavanit, U., & Punpuing, S. (2015). Rural-to-urban migration and changes in health among young adults in Thailand. Demography, 52(1), 233–257.

Niefert, M., Ott, N., & Rust, K. (2001). Willingness of Germans to move abroad. In R. Friedmann, L. Knüppel, & Lütkepohl (Eds.), Econometric studies (pp. 317–333). Münster: LIT.

Nielsen, S. S., & Krasnik, A. (2010). Poorer self-perceived health among migrants and ethnic minorities versus the majority population in Europe: a systematic review. International Journal of Public Health, 55(5), 357–371.

Patel, D. (2011). Occupational travel. Occupational Medicine, 61(1), 6–18.

Razum, O. (2009). Migration, Mortalität und der Healthy-migrant-Effekt. In M. Richter & K. Hurrelmann (Eds.), Gesundheitliche Ungleicheit. Grundlagen, Probleme, Perspektiven (pp. 267–282). Wiesbaden: VS.

Razum, O., Hajo Zeeb, H. S. A., & Yilmaz, S. (1998). Low overall mortality of Turkish residents in Germany persists and extends into a second generation: merely a healthy migrant effect? Tropical Medicine and International Health, 3(4), 297–303.

Rechel, B., Mladovsky, P., Ingleby, D., Mackenbach, J. P., & McKee, M. (2013). Migration and health in an increasingly diverse Europe. The Lancet, 381(9873), 1235–1245.

Reibling, N., Ariaans, M., & Wendt, C. (2019). Worlds of healthcare: A healthcare system typology of OECDCountries. Health Policy, 123(7), 611–620.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28.

Salaff, J. W. (2013). Return migration. In S. J. Gold & S. J. Nawyn (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Migration Studies (pp. 460–468). Milton Park, Abingdon: Routledge.

Sander, M. (2007). Return Migration and the “healthy immigrant effect”. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research (60).

Simon, J. G., de Boer, J. B., Joung, I. M. A., Bosma, H., & Mackenbach, J. P. (2005). How is your health in general? A qualitative study on self-assessed health. European Journal of Public Health, 15(2), 200–208.

Sjaastad, L. A. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 80–93.

Specht, J., Egloff, B., & Schmukle, S. C. (2013). Everything under control? The effects of age, gender, and education on trajectories of perceived control in a nationally representative German sample. Developmental Psychology, 49(2), 353–364.

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The new economics of labor migration. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 173–178.

Steiner, I. (2019). Settlement or mobility? Immigrants’ remigration decision-making process in a high-income country setting. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 20(1), 223–245.

Szkudlarek, B. (2010). Reentry-A review of the literature. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(1), 1–21.

Tabor, A. S., Milfont, T. L., & Ward, C. (2015). International migration. Decision-making and destination selection among skilled migrants. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 9(1), 28–41.

Uebelmesser, S. (2006). To go or not to go: Emigration from Germany. German Economic Review, 7(2), 211–231.

UNDP (2019). Human Development Index and its components. http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/HDI, accessed 1 October 2020.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2007). Longing for the good life: Understanding emigration from a high-income country. Population and Development Review, 33(1), 37–65.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2013). Explaining emigration intentions and behaviour in the Netherlands, 2005-10. Population Studies, 67(2), 225–241.

van Diepen, A. M. L., & Mulder, C. H. (2009). Distance to family members and relocations of older adults. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 24(1), 31–46.

Waibel, S., Rüger, H., Ette, A., & Sauer, L. (2017). Career consequences of transnational educational mobility: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review, 20, 81–98.

Williams, A. M., Jephote, C., Janta, H., and Li, G. (2017). The migration intentions of young adults in Europe: A comparative, multi-level analysis. Population, Space and Place 24.

Witte, N., & Guedes Auditor, J. (2021). Affluent lives beyond the border? Individual wage change through migration. In M. Erlinghagen, A. Ette, N. F. Schneider, & N. Witte (Eds.), The global lives of German migrants. Consequences of international migration across the life course. Cham: Springer.

Wu, S., Wang, R., Zhao, Y., Ma, X., Wu, M., Yan, X., & He, J. (2013). The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: a population-based study. BMC Public Health, 13, 320.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Stawarz, N., Ette, A., Rüger, H. (2021). Healthy Migrants? Comparing Subjective Health of German Emigrants, Remigrants, and Non-Migrants. In: Erlinghagen, M., Ette, A., Schneider, N.F., Witte, N. (eds) The Global Lives of German Migrants. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67498-4_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67498-4_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-67497-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-67498-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)