Abstract

With loyalty programs increasingly used as a competitive method by hotel brands, this study investigates the relationship between program size/satisfaction and brand direct website performance. Analyzing a unique database of loyalty program statistics, traffic levels/sources and engagement metrics from the top 50 global hotel brands, we find that size matters, with larger programs performing better in terms of both traffic and engagement, suggesting that efforts by hotel brands to grow membership are appropriate. Similarly, program satisfaction positively impacts both traffic levels and engagement, suggesting that brands should also focus on ensuring that existing members are happy with program benefits and operations. These findings are consistent irrespective of brand level, suggesting that all types of hotel brands can profit from leveraging loyalty programs.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Facing a highly competitive environment with a product that consumers increasingly regard as a commodity, hotels have intensified marketing efforts to attract and retain customers [44]. Chief amongst these is an increased emphasis on customer loyalty programs [12]. To drive more bookings through direct, and in particular online direct, channels, hotel brands are currently growing program membership as well as better leverage the resulting contact, demographic and transactional data to reach out and develop more personalised relationships with customers [29].

There is no doubt that developing loyalty is beneficial. Direct links have been found between with hotel service performance [13] and perceived value of the firm’s offer [41]. Similarly, multiple studies have demonstrated the connection with financial performance [see, for example, 10, 18 and 28]. However, while these studies establish this link in the macro sense, they do not determine the mechanism through which these improvements occur. Certain commentators theorise that these financial benefits arise from driving higher proportions of direct bookings, thus avoiding online travel agent (OTA) commissions and reducing customer acquisition costs, thus increasing profitability [25]. However, at present there is little empirical evidence to support these assertions.

The objective, therefore, of this paper is to delve deeper and investigate the link between hotel loyalty programs and direct website performance. As loyalty is primarily a marketing issue, analysis is carried out at the brand level, utilising a unique database of performance metrics from the fifty largest global hotel companies. The impact of both program size and satisfaction is investigated, with stickiness (time spent on a website and number of pages viewed) used as a proxy for engagement, and both traffic levels and source used to explore effectiveness. This paper complements and extends existing studies by deepening our understand of how loyalty programs can positively impact hotel performance. In addition, from a practical perspective the study helps practitioners better understand the value of loyalty programs to help make better strategic decisions as to future developments. The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Firstly, the literature on hotel loyalty programs is explored. The strategic/financial importance of driving bookings through direct channels is then established, with the role of loyalty programs in achieving this discussed. Using a unique database of loyalty program and performance website metrics, the effect of program usage by the top 50 global hotel brands is empirically analysed. Implications for both academia and industry are then presented, as well as suggestions for extensions and further research.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Loyalty Programs

According to [18], loyalty programs first became popular at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was only in the 1980s that they began to diffuse into travel, as airlines and hotel companies introduced formalised schemes to enhance their relationships with customers. These initiatives were driven by a belief that loyal customers exhibit long-term commitment to the brand, leading to increased buying intention [5]; higher revenue per customer; a willingness to pay more for comparable products/services; and reduced vulnerability to substitution by alternative brands [35]. Loyal customers are also thought to be more likely to use lower-cost, and in particular direct, channels as well as to generate additional ancillary revenues during their stay. In addition, leveraging data from loyalty programs allows firms to reduce their reliance on wasteful mass marketing and concentrate on targeting more efficient customised messages to an already receptive audience [16]. As a result, many feel that building and maintaining an effective loyalty program is important, particularly in the highly competitive and increasingly commoditised hotel sector [44].

However, comprehensive empirical studies investigating the effects of loyalty programs on performance in the hotel sector has been relatively rare [39]. [18] investigated how programs affect revenue, occupancy rate and operating margin, revealing that investment yielded a modest but positive impact. Similarly [46] found that loyalty programs positively impacted revenues and occupancy, but only in high-end luxury hotels. Other studies [see, for example, 11 or 28] address the issue only indirectly, using aggregate loyalty measures that do not reliably reflect loyalty spend. A more recent study [12] found that loyalty expenses positively impacted RevPAR, ADR, occupancy and gross operating profit. In a follow up study [10], Hua demonstrates that this is moderated by e-commerce spend.

Loyalty programs, however, are not without their challenges, leading some to challenge their effectiveness [9, 23, 43]. For example, [40] point out that consumer benefits from hotel loyalty programs remain functional and are easily replicated by competitors, making any advantaged gained unsustainable. With programs largely undifferentiated, switching costs are low. In addition, travellers typically belong to multiple programs, further reducing the bond with the brand [47]. As they permeate throughout the sector, their overall benefit decreases, with the result that hotel loyalty programs have now become a commodity that is expected, but not necessarily valued, by customers, and which generates questionable returns for its sponsoring company.

Despite this, it’s clear that hotel brands believe that loyalty programs are important for competing in today’s marketplace [47]. Cumulatively over 1.1 billion Americans are members of hotel programs, with, in contrast to other sectors, membership levels growing quickly [3]. This may be because the barriers to membership has been dramatically reduced [47]. In an effort to compete, particularly with the powerful global online travel agencies, many hotel chains have launched what O’Connor [30] has dubbed ‘the loyalty wars’, placing increased emphasis on their loyalty program as a competitive method and automatically enrolling anyone making a reservation by offering substantial instant discounts for sign-up, in effect artificially inflating their membership numbers. Although in the short term this may bring some benefits, particularly in making the brand more attractive to real estate owners for franchise/management contract deals, in the longer term it is problematic as these new members compromise the integrity of the database, polluting it with subjects with little intention of subsequently interacting with the brand. Also, this strategy has implications in terms of running cost [6]. Administrative and technological costs increase proportionately with size [18], and brands must also make allowance for reward points as liabilities on balance sheets [47]. Thus, growing the database with less than optimal subjects has negative implications from both a strategic and financial perspective.

Given the increased emphasis hotel companies place on loyalty programs, combined with the aforementioned database quality issues, it’s clear that a deeper understanding of the mechanisms through which loyalty programs deliver their promised benefits is needed. In addition, since loyalty programs typically operate at the brand level, there is a need to shift the unit of analyses away from the hotel property level used in previous studies to the chain (brand) level. Prior research specifically identifies the need for further research on the mechanisms of how customer loyalty tools affect firm performance [14, 43]. We answer this call, attempting to bring clarity to how loyalty programs affect hotel performance by investigating their impact on driving business through direct distribution channels.

2.2 Online Distribution

Over the past decades, technology has become deeply ingrained in the hotel marketing, sales and distribution processes [2]. In particular Internet-based distribution has become a key feature of hotels, with customers increasingly searching for, and booking, their hotel stays through online (web and mobile) channels [31]. Due to the perishable nature of the hotel product, having the right mix of distribution channels is important in terms of maximise revenue opportunities [19]. As a result, most hotels use a dynamic portfolio of direct and indirect, and online and offline channels, to reach out to the customer in an effective and efficient manner [26].

However in recent years overall distribution costs have been rising due to the rising prominence of online intermediaries in the hotel distribution process [33]. OTAs provide consumers with a wide range of value-added services, including supplemental information on destinations [17], room rate, facility and amenity comparison facilities [22] as well as, in many cases, more attractive pricing [7]. As a result, their value proposition is highly attractive from a customer perspective, with the result that online penetration figures have shifted substantially towards the indirect OTA route [21]. From a financial perspective this has two major implications for hotels. Firstly, selling through OTAs necessitates either the payment of a commission or the provision of net rates at a substantial discount, decreasing the resulting net revenue [42]. Alternatively, hotels have to invest more marketing funds to compete with the OTAs for the customer, again driving up costs and reducing profitability. In both cases the presence of OTAs in the marketplace has a significant effect on the competitiveness of hotels over reliant on these channels [2].

Direct channels, in contrast, have lower transaction costs and also allow hotels to communicate with customers more efficiently [15]. [34] suggest strategies for encouraging customers to book directly, in particular through the hotel’s or brand’s direct website. One way of driving such bookings is by nurturing a direct relationship with customers through loyalty programs operations. [37] hold that it requires less effort and is less costly to retain current customers rather than trying to attract new ones. And in addition, rather than booking through third parties, loyal customers tend to book through direct channels and in particular the hotel’s direct web presence [12]. Thus, attempting to better leverage loyalty programs to decrease dependence on OTAs, thus driving higher proportions of higher-margin direct business and enhancing profitability, would appear to be an attractive strategy for hotels.

To facilitate this process, this study specifically examines two interrelated issues. Firstly, as discussed above, hotel brands use loyalty programs to enhance customers’ perceived value, brand image and trust, leading to enhanced customer engagement [14]. As a result, the traditional “consider -> evaluate -> buy -> enjoy -> advocate -> bond” purchase continuum is short-circuited, prompting loyal customers to skip earlier stages and move directly to “buy” [4]. This is particularly important in the hotel sector, which compete not only with each other but also with the powerful OTAs whose added value includes expediting consumer access to product choice and facilitating comparative evaluations. Thus, locking customers into an abridged customer journey is advantageous, reducing or eliminating the threat of substitution, resulting in higher direct sales [8].

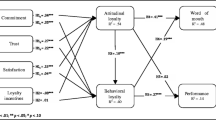

The brand’s direct website plays a key role in this strategy [26]. Since loyal customers tend to book through the brand’s direct web presence [43], we theorise that there is a relationship between loyalty program effectiveness and brand website performance. With a deeper connection to the brand, loyal customers tend to be more engaged, browse more information and spend longer on the brand website [38]. We operationalise loyalty program effectiveness using a membership satisfaction score but given the afore mentioned efforts to grow loyalty program membership numbers, examining whether program size affects website performance is also relevant. This is assessed in two ways: traffic (number of unique visitors arriving on the website per month) and the resulting engagement of this traffic [20]. This is operationalised as “stickiness’ - the site’s ability to retain visitors as measured by number of pages viewed by each visitor and time spend on the site [36]. Bounce rate, the percentage of visitors who view only a single page (regarded as a negative sign in terms of user satisfaction) was also investigated. Thus, we put forth the following hypothesis:

- H1a::

-

Consumer satisfaction with hotel loyalty programs positively influences brand website traffic.

- H1b::

-

Hotel loyalty program size positively influences brand website traffic.

- H2a::

-

Consumer satisfaction with hotel loyalty programs positively affects brand website engagement.

- H2b::

-

Hotel loyalty program size positively affects brand website engagement.

While absolute traffic levels are important, the source of this traffic is also relevant. If loyalty programs are effective, they should have a positive effect on how the website attracts visitors. With an established connection to the brand, program members should already be aware of the brand’s existence and more likely to navigate directly to its website. They also could arrive through brand marketing efforts that leverage the loyalty database to communicate with members, prompting them to reengage [43]. In contrast, transient customers, as they are less aware of the brand and do not receive promotional efforts, arrive through search, and in particular paid search, where the resulting transaction costs negate many of the benefits of capturing a direct booking [32]. Thus, we put forth the following hypothesis:

- H3a::

-

Consumer satisfaction with hotel loyalty programs positively influences traffic levels from direct sources.

- H3b::

-

Loyalty program size positively influences traffic levels from direct sources.

3 Research Methodology

Research on consumer behaviour is traditionally dominated by survey data, where intent, rather than actual behaviour, is measured [27]. However, with online channels, clickstream data, which measures actual interactions rather than declared intent or perceptions, can be used [20]. For this study, a unique dataset was assembled from secondary sources. A ranked list of the top 50 global hotel brands were obtained from Brand Finance [1]. Satisfaction scores with the loyalty programs of these brands was obtained from J.D. Power. Unique visitor, metrics traffic sources and other online measures for the direct brand websites for December 2019 were scraped from SimilarWeb.com in July 2020. Data on size (number of hotels and rooms respectively) was retrieved for 2019 from the Hotels 325 Report 2020 [45], while data on loyalty club membership levels was compiled from the 2019 annual reports of the respective hotel companies. As, in line with past studies [46], we expected more upmarket brands to perform better, following [24] we used Consumer Reports classification of hotel brands to create four categories; luxury (e.g. Ritz Carlton), upscale (e.g. Marriott), midscale (e.g. Hampton Inn), and budget (e.g. Ibis) and performed post-hoc analysis to investigate differences between groups.

4 Results

As can be seen from Table 1, the loyalty programs studied have a substantial number of members (mean = 83 million), with high variability (std dev of over 38 million). Satisfaction scores were more homogeneous, with a mean of 838/1000, and std dev of only 38, suggesting a high degree of satisfaction amongst customers with hotel loyalty programs. As reflects their status as the world’s largest chains, the brands studied were also substantial in size, with a mean number of rooms and properties of nearly 96,939 and 757 respectively. Websites attracted an average of almost 18 million monthly visitors, again with high variability with a standard deviation of over 15 million. The average visit time was over 6 min, with the typical visitor viewing just over four pages. Brand’s websites were not very successful at retaining visitors, with a mean bounce rate of over 45%. Search was the primary traffic source (mean = 45.53%), followed by direct navigation (32.21%). Other sources were more minor (10% or less), confirming the well establish power of brand in hotel distribution [32].

To examine the relationship between program size and stickiness, Pearson’s Correlations were calculated. As can be seen from Table 2, there is a strong and statistically significant relationship between number of members in a brand’s program and traffic to its website, lending support to Hypothesis 1b. Similarly, programs with higher number of members profited from deeper engagement, with visitors viewing more pages and bouncing less often. However, this advantage does not translate into time spend on the site, with the relationship between program size and visit length not significant. Given the variability in brand scale, it was though important to control for chain size, as presumably larger brands, with more significant global presence, should be able to attract more members. For that reason, the same analyses were performed using two calculated metrics – members per room and members per hotel – to neutralise the effect of chain size. As can be seen from Table 2, in both cases the relationships remained both positive and significant, although their degree was substantially weaker, suggesting that brand scale does have a substantial effect.

In terms of the program satisfaction, there is a strong and significant association with both average number of pages viewed and bounce rate (in this case negative, suggesting that programs with higher satisfaction rates result in lower levels of site abandonment), in both cases supporting H2a. The relationship with visit length, although significant, was less strong, but still adds support to H2a. Lastly, the relationship with traffic level, although positive and significant, was weaker, suggesting that program size may be more important than program satisfaction.

Given differing service levels among hotel brands and their potential effect on loyalty development, an important question was to investigate whether brand level (economy, midscale, upscale, luxury) affects traffic and stickiness. A one-way MANOVA revealed no statistically significant difference in the variables under investigation based on brand level, F (12, 111) = 1.84, p < .15 8; Wilk’s Λ = 0.683, suggesting that service levels have no significant effect on the relationship between loyalty program size/satisfaction and the selected elements of brand website performance.

Lastly, in terms of traffic sources, we found little evidence to support the theory that brands with larger and/or better loyalty programs drive larger proportions of their web traffic through direct navigation and/or direct marketing channels. As can be seen from Table 3, the relationship between program size and proportion of traffic driven directly is both non-significant and weak, causing us to reject hypothesis 3b. There is, however, some evidence that program size is associated with the proportion of traffic generated through both email and social media. These effects are, however, based on the absolute scale of the loyalty programs concerned, as statistical significance disappears when controlled by number of rooms/properties.

Program satisfaction has a similar effect, with the association with percentage of direct traffic both insignificant and weak (causing us to reject H3a), but the associations with both traffic from email and from social both tested significant, positive and moderately strong. In addition, the association between program satisfaction and traffic from both referrals and display advertising is significant and negative, providing evidence that better loyalty programs drive higher levels of direct traffic. As with stickiness, post-hoc analysis was carried out to establish whether brand level affected how the brand sites generated traffic. The resulting one-way MANOVA revealed no statistically significant difference, F (12, 111) = 1.616, p < .490; Wilk’s Λ = 0.57, suggesting that brand level no effect on overall findings.

5 Conclusion and Discussion

With loyalty programs having become a competitive necessity for any company wanting to work in travel, this study explores the impact of loyalty program size/satisfaction on the direct website performance of the world’s largest hotel brands using a unique dataset compiled from multiple secondary sources. Using a brand rather than a property perspective, the study extends and complements previous work [11, 12, 28], enhancing our understanding of how hotel loyalty programs positively affect hotel operations and performance.

The results demonstrate that, when it comes to hotel loyalty programs, size clearly matters. Analyses revealed a strong, statistically significant, relationship between number of members in a brand’s loyalty program and traffic to its website. When chain size is controlled, the relationship remains significant although decreasing in strength. In addition, there is a positive association between program size and both pages viewed and bounce rate. Overall bigger is better, with larger programs seeing concrete results in terms of both traffic levels and site engagement, suggesting that brands’ current efforts to grow membership by offering instant discounts may be appropriate. However, size is less important in terms of how visitors arrive on the site. Despite theoretical benefits, there is no significant relationship between program size and proportion of traffic arriving through direct navigation. Instead the most common traffic source is search, suggesting that hotel loyalty programs may not be generating true loyalty or recognition. That being said, the proportion of traffic from email and social media does associate with program size, suggesting that hotel brands may be leveraging economies of scale to reach out more successfully to members through direct marketing efforts.

In terms of loyalty program satisfaction, a significant and positive association was found with both traffic levels as well as all aspects of stickiness. Similarly, no relationship was found with proportion of direct traffic, although satisfaction did influence traffic driven through brand promotional channels (in particular social media and to a lesser degree email). Furthermore, there was a significant negative association with referrals and display advertising, adding evidence that brand-driven marketing activities, supported by data from the loyalty program, have a positive effect. These findings suggest that having a better program helps generate more, and more engage, traffic, implying that hotel brands should invest in ensuring members are happy with program operation and benefits. Finally, despite conjecture that loyalty programs work better at higher service levels, our study found no differences between the levels of brands included, suggesting, in contrast to prior studies, that loyalty program size and satisfaction have similar effects irrespective of brand level.

As with most research, the study suffers from several limitations. First, traffic, rather than bookings or booking value, was used as a key success metric due to the challenges of accessing such sensitive information. While not a full proxy, the relationship between traffic and resulting sales has been well documented and arguments can be made for its relevance. Nevertheless, future researchers could increase validity by gaining access to appropriate booking data. Second, the study was carried out at a single point in time and focused on the top 50 global hotel brands. Future researchers might consider adopting a more longitudinal approach and including a wider sample of hotel brands to increase the generalisability of the findings. Lastly, traffic sources are based on last touch attribution. In reality customers use multiple routes consecutive to arrive on a website. For example, they may see a social media post which caused them to search for the hotel brand before clicking on a paid link and visiting the site. As only the last point of contact is recorded, the relative importance of other traffic sources may be underreported. More sophisticated attribution models are now available and further studies could incorporate these into their analyses to develop a more comprehensive understanding of the issue.

References

Brand Finance (2019) Hotels 50 2019. https://brandfinance.com/knowledge-centre/reports/brand-finance-hotels-50-2019/

Buhalis D, Harwood T, Bogicevic V, Viglia G, Beldona S, Hofacker C (2019) Technological disruptions in services: lessons from tourism and hospitality. J Serv Manag 30(4):484–506

BusinessWire (2017) U.S. Customer Loyalty Program Memberships Reach Double Digit Growth at 3.8 Billion, 2017 COLLOQUY Loyalty Census Reports. BusinessWire

Edelman D (2010) Branding in the digital age: youʼre spending your money in all the wrong places. Harv Bus Rev 88(12):62–69

Evanschitzky H, Ramaseshan B, Woisetschläger DM, Richelsen V, Blut M, Backhaus C (2012) Consequences of customer loyalty to the loyalty program and to the company. J Acad Mark Sci 40(5):625–638

Ferguson R, Hlavinka K (2007) The COLLOQUY loyalty marketing census: sizing up the US loyalty industry. J Consum Mark 24:313–321

Gazzoli G, Kim W, Palakurthi R (2008) Online distribution strategies and competition: are the global hotel companies getting it right? Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 20:375–387

Han H, Hyun S (2012) An extension of the four-stage loyalty model: the critical role of positive switching barriers. J Travel Tour Mark 29:40–56

Hikkerova L (2011) The effectiveness of loyalty programs: an application in the hospitality industry. Int J Bus 16(2):150

Hua N, Hight S, Wei W, Ozturk AB, Zhao X, Nusair K, DeFranco A (2019) The power of e-commerce. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 31(4):1906–1923

Hua N, Morosan C, Defranco A (2015) The other side of technology adoption: examining the relationships between e-commerce expenses and hotel performance. Int J Hosp Manag 45:109–120

Hua N, Wei W, Defranco A, Wang D (2018) Do loyalty programs really matter for hotel operational and financial performance? Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 30:2195–2213

Kandampully J, Hu HH (2007) Do hoteliers need to manage image to retain loyal customers? Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 1:435–443

Kandampully J, Zhang T, Bilgihan A (2015) Customer loyalty: a review and future directions with a special focus on the hospitality industry. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 27(3):379–414

Kang B, Brewer KP, Baloglu S (2007) Profitability and survivability of hotel distribution channels. J Travel Tour Mark 22(1):37–50

Lau K, Lee K, Lam P, Ho Y (2001) Web-site marketing for the travel-and-tourism industry. Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 42(6):55–62

Law R, Leung K, Wong R (2004) The impact of the Internet on travel agencies. Int J Contem Hosp Manag 16(2):100–107

Lee JJ, Capella ML, Taylor CR, Luo M, Gabler CB (2014) The financial impact of loyalty programs in the hotel industry: a social exchange theory perspective. J Bus Res 67(10):2139–2146

Lei SN, Wang D (2019) The impact of distribution channels on budget hotel performance. Int J Hosp Manag 81:141–149

Leung R, Law R (2008) Analyzing a hotel website’s access paths. In: O’Connor P, Hopken W, Gretzel U (eds) Information and communication technologies in tourism 2008: proceedings of the international conference in Innsbruck, Austria. Springer, Vienna, pp 255–266

Martin-Fuentes E, Mellinas J (2018) Hotels that most rely on Booking.com – (OTAs) and hotel distribution channels. Tour Rev 73:465–479

Masiero L, Law R (2016) Comparing reservation channels for hotel rooms: a behavioral perspective. J Travel Tour Mark 33(1):1–13

Mattila A (2006) How affective commitment boosts guest loyalty. Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 47:174–181

Mattila A (2006) The impact of affective commitment and hotel type in influencing share of wallet. J Hosp Leis Mark 15:55–68

McCall M, Voorhees C (2009) Drivers of loyalty program success: an organizing framework & agenda. Cornell Hosp Q 51(1):35–52

Morosan C, Jeong M (2008) Users’ perceptions of two types of hotel reservation Web sites. Int J Hosp Manag 27(2):284–292

Nguyen DH, de Leeuw S, Dullaert WEH (2018) Consumer behaviour and order fulfilment in online retailing: a systematic review. Int J Manag Rev 20(2):255–276

O’Connor P (2008) E-mail marketing by international hotel chains: an industry-practices update. Cornell Hosp Q 49(1):42–52

O’Neill J, Hanson B, Mattila AS (2008) Relationship of sales and marketing expenses to hotel performance. Cornell Hosp Q 49(4):355–363

O’Connor P (2017) The great loyalty rate debate. https://www.phocuswire.com/The-great-loyalty-rate-debate. Accessed 3 Jan 2020

O’Connor P (2019) Online tourism and hospitality distribution: a perspective article. Tour Rev 75(1):290–293

O’Connor P (2020) Brandjacking: the effect of Google’s 2018 keyword bidding policy changes on hotel website visibility. In: Neidhardt J, Wörndl W (eds) Information and communication technologies in tourism: proceedings of the international conference in Surrey, United Kingdom, pp 243–254

O’Connor P, Frew A (2004) An evaluation methodology for hotel electronic channels of distribution. Int J Hosp Manag 23(2):179–189

O’Connor P, Piccoli G (2003) “Marketing hotels using global distribution systems” Revisited. Cornell Hosp Q 44(5):105–114

Oliver RL (1999) Whence consumer loyalty? J Mark 63:33–44

Plaza B (2011) Google analytics for measuring website performance. Tour Manag 32(3):477–481

Reichheld F, Sasser W (1990) Zero defections: quality comes to services. Harv Bus Rev 68(5):105–111

Roy S, Lassar W, Butaney G (2014) The mediating impact of stickiness and loyalty on word-of-mouth promotion of retail websites: a consumer perspective. Eur J Mark 48(9/10):1828–1849

Serra Cantallops A, Salvi F (2014) New consumer behavior: a review of research on eWOM. Int J Hosp Manag 36:41–51

Shoemaker S, Lewis RC (1999) Customer loyalty: the future of hospitality marketing. Int J Hosp Manag 18(4):345–370

Siu NY-M, Zhang TJ-F, Dong P, Kwan H-Y (2013) New service bonds and customer value in customer relationship management: the case of museum visitors. Tour Manag 36:293–303

Stangl B, Inversini A, Schegg R (2016) Hotels’ dependency on online intermediaries and their chosen distribution channel portfolios: three country insights. Int J Hosp Manag 52:87–96

Tanford S, Shoemaker S, Dinca A (2016) Back to the future: progress in hotel loyalty marketing. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 28:1937–1967

van Riel AC, Victorino L, Verma R, Plaschka G, Dev C (2005) Service innovation and customer choices in the hospitality industry. Manag Serv Qual 15(6):555–576

Weinstein J (2020) Hotels 325. Hotelsmag.com: 22–38

Xie LK, Chen C-C (2014) Hotel loyalty programs: how valuable is valuable enough? Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 26(1):107–129

Xiong L, King C, Hu C (2014) Where is the love?: Investigating multiple membership and hotel customer loyalty. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 26:572–592

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

O’Connor, P. (2021). Loyalty Programs and Direct Website Performance: An Empirical Analysis of Global Hotel Brands. In: Wörndl, W., Koo, C., Stienmetz, J.L. (eds) Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2021. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65785-7_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65785-7_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-65784-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-65785-7

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)