Abstract

In developing countries, where competing priorities often overwhelm capacity, the sweeping BEPS initiative can serve to motivate and justify the devotion of limited resources to the international tax field. It is hard to say whether all of the BEPS Actions are “suitable” for developing countries as their size, level of maturity, and many other factors that influence taxation vary drastically. An evaluation of domestic circumstances will help to determine the tax regime’s compatibility with the BEPS recommendations. This initiative represents a minimum level of commitment that is necessary to ascertain sustainable BEPS implementation. Certain attributes will influence the feasibility of this implementation such as the adaptability of the juridical system to enforce new regulations, the technological infrastructure, the capacity to process and protect mass information, efficient risk assessment procedures and analysis tools, and continual training and development workshops, among others. The BEPS project is still quite young; however, thanks to contributions from CIAT member countries, the BEPS Monitoring database was created. This can provide us with a general overview of how extensively each BEPS Action has been implemented in these countries so far.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Sustainable BEPS implementation

- Latin America and Caribbean tax systems

- Mutual agreement and compliance

- Close legislative gaps

- Observer’s position of developing countries

- Political alignment

- Harmonization and increase alignment of the tax regimes

- BEPS minimum standards

- Operational aspects of BEPS implementation

1 Introduction

This chapter attempts to analyze some of the potential implications that the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project could have on member countries of the Inter-American Centre of Tax Administrations (CIAT) in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region. This includes strategic considerations for deciding whether to implement BEPS; tactical aspects regarding the manner and extent to which the proposals could be implemented; and operational aspects relating to the current implementation. It is important to note that CIAT countries from this region present extensive differences in their size, context, tax regulations, and levels of experience. Information taken from CIAT’s Transfer Pricing Database shows us that some of the countries in the region have a limited treaty network with only one or two countries while others have over 30 treaties in force (CIATData 2016). Most LAC countries have transfer pricing legislations, albeit only a few countries have an extensive level of practice with them (CIATData 2018b). Some countries have efficient risk assessment tools that help them identify when to apply anti-abuse rules, while other countries are only beginning to introduce these rules (CIATData 2018a).

When the BEPS project first started in 2013, the OECD/G20 and the international tax community had many challenges ahead of them. The technical concepts dealt with in each of the action points had to be explained and understood clearly by authorities and technical officials, thereby building the momentum and support necessary to drive forward a discussion of these issues on an international scale. The Inclusive Framework (IF) on BEPS was created for interested countries to join the initiative and participate in the discussions under an “equal footing” criteria, with the goal of reaching a general consensus regarding proposed solutions (OECD 2019). Many of the BEPS objectives need adoption on a global scale to be most effective; this implies persuading the domestic political will of countries toward mutual agreement and compliance with the BEPS proposals. In this regard, the BEPS discussions have helped to attract the support and justification needed to pass tax reforms, close legislative gaps, and occasionally increase the disposition of available resources for the tax administrations. Moreover, it is necessary to recognize that in practical terms, developing countries acted as observers in this process. Nevertheless, it may be expected that the future influence of developing countries on BEPS will be proportional to the experience they have gained in their interactions with BEPS.

2 Strategic Aspects: Why Implement BEPS?

This section will attempt to identify how the BEPS proposals may fit into the tax vision of a developing country and the elements to be evaluated prior to or during its implementation. In order to assess the feasibility of BEPS, a country must first understand the issues in each BEPS Action: the objectives, the potential impact on tax compliance, and other expected results (including the potential impact on international relations). The decision to adopt BEPS proposals may be influenced by internal and external forces. Internally, the tax administration may wish to attain better results, increase the scope of the tax base, or reduce base eroding activities. Prior to BEPS, it may have been more difficult for countries to impose taxation on a corporation that creates value in their jurisdiction but does not declare it or provide fair remuneration for it; however, BEPS Actions 8–10 and the substance requirements in Actions 5 and 6 contain proposals that may help retain the value and corresponding taxable base generated in the country. For example, a new assessment mechanism allocates the value and control over intangible assets to the entities that perform the Development, Enhancement, Maintenance, Protection, and Exploitation (DEMPE) functions related to that intangible (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project 2015a). Externally, motivations to implement BEPS could stem from the wish to avoid international sanctions. For example, amending or derogating a “harmful tax regime” (as per the criteria of Action 5) could lead to the country’s name being removed from a blacklist. Similarly, from the point of view of the ministry of finance, the commercial impact of BEPS and its effect on foreign direct investments should be analyzed (e.g., the impact on the economy of implementing actions related to tax transparency or exchange of information).

If a country considers that the BEPS recommendations are feasible and could contribute to achieve the objectives of the tax administration, then decisions must be taken to outline the path toward their implementation. To ascertain the highest benefits, a certain level of international harmonization is required. For this, the government may want to consider joining the IF (although this could be an overwhelming commitment for a developing country as it requires a budget to cover the annual membership fee, the travel expenses associated with the country’s attendance at meetings and events, and the technical capacity to participate in the “international decision-making process”). The IF dictates that all countries must implement the “BEPS package” minimum standards, regardless of their individual characteristics (OECD 2019). However, not all countries have the ready capacity (or the interest) to implement some of the recommendations (e.g., a small country without transfer pricing legislation having to implement Action 13). From this domestic point of view, the mandatory element of the IF may be perceived by some as unreasonable. Nevertheless, international harmonization and increased alignment of the tax regimes are necessary to further progress, foment cooperation, and reduce loopholes found throughout the various tax systems.

A country’s political system will also influence their participation in the IF. For example, the commitments of a country’s leadership position may be debilitated by frequent changes in government. It follows that, when the current government commits to the IF and makes BEPS a part of their fiscal strategy, their efforts may be backtracked once a new political party is elected. This situation hasn’t happened yet at the political level in the LAC region. However, it has been observed at an operational or technical level (e.g., resources were allocated and then retracted; laws were repealed or stopped somewhere along the legislative process). A similar plight follows the opposing scenario; if the leadership role has been in the same hands for an extended period of time, ministers and high-ranking government officials may be resistant to foreign commitments or any changes in the tax code, consequently blocking the decision to join the IF and inhibiting the prospective implementation of BEPS.

One factor to keep in mind when joining the IF (or when unilaterally implementing BEPS) is the potential for disruption in key economic sectors. Taxpayers may be hesitant and resistant toward any measures that they perceive could violate their tax certainty. Furthermore, taxpayers in sectors that enjoy preferential tax treatment or benefit from tax incentive programs are likely to protest as there is a chance these could be dissolved under the BEPS proposals. A country should contemplate the potential resulting impact on these sectors when making their decisions. Furthermore, it is important for the administration to uphold neutrality and build trust in the eyes of the taxpayers. Maintaining clarity and strong communication can be an important tool to get everyone on board with the changes. Moreover, the tax administration may offer certain concessions such as the possibility to reveal assets or transactions, without punitive consequences, during the months prior to the BEPS proposals coming into effect (i.e., a grace period).

In summary, the advantages of implementing BEPS may include increased efficiency of the tax system, improving the country’s international reputation, association with a sweeping global initiative, and the opportunity to motivate political will and knowledge on issues which—in the LAC experience—countries have been generally apathetic toward. On the other hand, the barriers or challenges may include the allocation of scarce resources in the face of competing priorities and the feasibility to comply in due course with the stringent IF commitments, among others.

3 Tactical Aspects: How to Implement BEPS?

Once the strategic aspects have been analyzed, a country must decide on the tactical plans to achieve its successful and sustainable implementation. This analysis takes into account the country context and the available resources and infrastructure in place. In general, the main barriers that developing countries often experience include the lack of necessary information and technology, insufficient control processes and risk analysis tools, slow or inefficient juridical infrastructure and administrative processes, lack of expertise or trained officials for high-level technical functions, and others depending on individual country characteristics. Tactical considerations also include decisions on the technical aspects of BEPS: whether to sign the MLI, which treaties to list, what reservations to make, which optional clauses to choose within the minimum standards, and to what extent the elective action points will be implemented. These decisions require studies, research, discussions with domestic stakeholders, etc. to forecast the potential effects. Decisions regarding technical aspects may require an investment in human resources as those officials involved in the process should fully understand the issues dealt with in each of the BEPS Actions and how these will interact with the current tax legislations. If necessary, capacity building workshops or training events could be provided. Similarly, post-implementation, the country will need tax experts who understand and are able to sustain the objectives of the regulations in order to make and try cases relating to BEPS abuse. It is not enough for the rules to merely exist; there needs to be the tools and human capacity to process, understand, and enforce them. Otherwise, without the perception of consequences, taxpayer behaviors will remain unchanged.

Sustainability is key as implementation is only the first stage in the process; countries need to ensure subsequent capacity and political stability to enforce the changes. For the tax administrations of developing countries, where juridical and administrative resources may be lacking, technical assistance can play a fundamental part. The role of organizations such as CIAT is to coordinate and provide support for tax administrations, aiming to strengthen their ability to evaluate the strategic, tactical, and operational aspects surrounding BEPS. As a counterpart to the efforts provided by international organizations and donors, tax administrations should prioritize the infrastructure and personnel needed to generate an optimal environment that capitalizes on the benefits from this technical assistance. In this regard, the performance indicators of Action 11 are useful to follow up on the progress. Action 11 tries to overcome the difficulties that arise from a lack of information regarding corporate taxation by creating datasets and analytical tools to better monitor the economic impacts of tax avoidance and BEPS-related changes (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project 2015d). Thus, keeping authorities and peers informed on the progress of BEPS motivates its continual support. Going one step further, Action 11’s range of attributes could be expanded by including risk assessment indicators that allow tax administrations not just to monitor BEPS but also to identify risks for better applying the BEPS recommendations.

Choosing the specific Actions to be implemented will depend on the characteristics of the tax regime and the domestic political circumstances. Even those Actions which a country has not chosen to implement yet can serve to guide long-term objectives and shed light on future policies. A country may want to provide its taxpayers with clarification on the BEPS modifications with reference to the corresponding BEPS documents published by the OECD (e.g., “For further understanding of the documentation requirements see the OECD’s Action 13: 2015 Final Report”). However, it is advisable to make clear whether any future changes or updates to the referenced BEPS/OECD documents will assert influence on the interpretation of the legislation as this could lead to legal uncertainty.

3.1 The Minimum Standards

As previously mentioned, joining the IF or signing the MLI is a strategic option that requires adherence to the four BEPS minimum standards (encompassed in Actions 5, 6, 13, and 14). This section will analyze, in consecutive order, their potential implications.

The minimum standard of Action 5 requires the review of preferential tax regimes and the implementation of a transparency framework for tax rulings (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project 2015b). This relies on the country’s acquiescence toward the OECD criteria that deems a regime as “harmful.” This could cause major disruptions in the functioning of the tax systems for many LAC countries that use incentives and safe harbor regimes to attract foreign investment, entice voluntary compliance, and attempt to increase short-term collection. However, in the long term, these measures may prove beneficial as it has often been found that tax incentives result in unsustainable effects, many times losing the country more revenue than they bring in. These incentives can be especially unfavorable when dealing with sectors that have high exit barriers or with companies that need the natural resources in that specific location.

The minimum standard found in Action 6 includes the addition of an anti-abuse rule: the principal purpose test (PPT) and/or a limitation on benefits (LOB) rule depending whether it is simplified or detailed, as well as the inclusion of a paragraph in double tax treaties that defines the purpose of the treaty as being “for the evasion of double taxation without creating opportunities for non-taxation” (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project 2015e). In the LAC region, there may be less initial attention paid to this minimum standard as there are only a few countries that count on an expansive treaty network. As of 2016, the LAC CIAT member countries had an average of 20 treaties per country (CIATData 2016).Footnote 1

Regardless of their treaty network relevance, the concepts touched upon in Action 6 may be used to fortify domestic regulations (e.g., requiring taxpayers to meet substance-over-form, economic reality, or principle purpose tests). However, for a developing country where the tax administrations’ resources and expertise are limited, it could be difficult to apply and defend an anti-abuse rule, such as the PPT, especially when arguing against corporations with unlimited resources. Tax courts can look forward to gaining experience on this and other BEPS developments in the forthcoming years.

Arguably, one of the most adopted BEPS proposals is the Country-by-Country (CbC) report, the minimum standard of Action 13. The CbC allows information from multinational enterprises to be reported and exchanged through a standardized format (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project 2015f). The OECD further assists countries to implement this minimum standard by offering to join the CbC Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement (CbC MCAA) and other legislative proposals. For developing countries with a restricted information regimes or limited access to databases, this Action is especially useful to increase the administrations’ knowledge regarding taxpayer activities. As with any information regime, continual improvements are necessary to identifying the best procedures for evaluating the veracity of the information presented and avoiding undesired results in the risk assessment process.

The minimum standard of Action 14 consists of 21 elements dealing with preventing disputes, availability and access to mutual agreement procedures (MAP), resolution of MAP cases, and the implementation of MAP agreements (OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project 2015c). Although quite comprehensive, LAC countries may perceive its impact to be less consequential due to the lack of treaties and the general inexperience of MAP usage in the region (see Fig. 3.1).

Availability of map in the region as of 2018. 1) Uruguay is in the process of resolving their first mutual agreement procedure started in 2018. Source: CIATData (2019)

Hesitation to implement the Action 14 standard stems from the possibility for a country to lose a portion of its tax base as a result of the dispute resolution or arbitration. Further hesitation arises when contemplating the optional “mandatory arbitration clause” that requires a level of commitment and compromise in terms of sovereignty. This Action requires extensive training of MAP experts that can present and defend their arguments (especially when negotiating with more experienced countries). In order to comply with the main intention of objectivity, arbitration (mandatory or not) requires some minimum neutrality conditions that may be hard to achieve in the LAC context. Nevertheless, this Action is highly relevant in an arena where disputes are imminent in several cases.

4 Operational Aspects: What Is Happening with BEPS?

It follows that, once the BEPS proposals have been implemented, they must be enforced using adequate tools and processes. One of the biggest challenges is first to detect the BEPS risks and then to know how to manage it, applying the correct measure in a timely manner following its identification. As mentioned above, some countries have observed positive results from the use of concessions or tax benefits that motivate taxpayers to regularize their tax positions prior to applying BEPS measures or tax transparency rules. Another challenge involves maintaining fluidity and not overwhelming the judicial system in this new context where disputes are likely to arise. Thus, the elements found in Action 14 and/or other mechanisms for avoiding disputes are imperative.

Through domestic and international cooperation on tax matters, the administration can attain more information with which to prepare and defend their assessments. In this regard, CIAT has created a database on harmful tax planning, providing a forum for countries to share their experiences, specifically emphasizing how they were able to identify the taxpayers’ risky behavior and which tools where used to justify their contentions. As can be seen in the database, domestic rules similar to the general anti-avoidance rule seen in Action 6 give an option for countries to denunciate taxpayer behaviors (acting as a sort of “blanket clause”). The Availability of Public Information tool (DIP) is another CIAT product for tax administrations that facilitates the identification of public information, useful for verifying the taxpayers’ situation (through a database of withholding agents, real estate registry, company registry, etc.).Footnote 2

4.1 Findings from the CIAT BEPS Monitoring Initiative

The OECD/G20 have been consistent in their efforts to promulgate the BEPS proposals, and—based on the quantity of countries that have joined the IF—their efforts have paid off. Nevertheless, the project is only 6 years old which is a short amount of time for proposals to be presented, adopted, implemented, and applied. Thus, an analysis of the long-term effects that the BEPS project has on a developing country’s administrative and judicial processes is yet unavailable. In the LAC region, many countries find themselves in the stage of capacitating their administration and judicial system to better handle the issues in the newly adopted regulations. Moreover, a few of the countries have begun to report positive results pertaining to the exchange of information, the elimination of preferential regimes, and the fortification of their transfer pricing regimes.

To this extent, in 2018–2019 CIAT carried out a study relating to the adoption of BEPS Actions across its member countries. Representatives from the tax administrations of these countries indicated which of the recommendations from each Action had been implemented and whether they were “totally implemented” (including all of the recommendations found in the Action report) or if they were “partially implemented” (including only some of the recommendations). The detailed information as to which specific recommendations were implemented by each country is available in the resulting “BEPS Monitoring database” available at CIATData.Footnote 3 It must be noted that CIAT merely tallied the statements made by the tax administrations relating to their level of adoption of the BEPS recommendations. Therefore, CIAT does not pretend for this to be an official measure or review on the level of implementation such as that done by the IF.

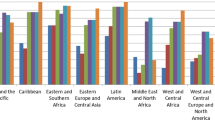

For the purposes of this chapter, we have extracted the information relating only to the CIAT member countries from the LAC region. Figure 3.2 shows the “popularity” of each Action as determined by their implementation.

It should be noted that the Actions which encompass the minimum standards (5, 6, 13, and 14) have an inherent bias that thrusts forward their implementation. The highest levels of total adoption are seen in Actions 5 and 13 (in which all of the recommendations were included as part of their implementation). Action 6 is shortly behind along with Actions 3 and 7 which, notably, are not minimum standards. The actions which have not been adopted to their full extent by any country are Actions 1, 2, 11, and 14. Moreover, the potential issues relating to Action 14 mentioned in the section above (i.e., the concession of sovereignty) could explain why there has not been a country that has totally adopted all of the recommendations related to this action.

In opposition, Fig. 3.3 shows the quantity of BEPS Actions implemented by each country without identifying which of the 15 Actions were implemented, only how many.

Those countries with a total level of implementation demonstrate a strong adherence toward the BEPS proposals. That being said, for a developing country, the attainment of even partial implementation shows strong commitment and potential (depending on the context). Through this disposition, it may be acceptable to disregard the difference between them, considering partial and total implementation together to enhance the visual accessibility of the information. Thus, the amalgamation provides us with the total quantity of Actions being implemented, as seen in Fig. 3.4.

Total number of BEPS actions adopted per country in 19 LAC CIAT member countries (without differentiating between partial and total implementation), as of June 2019. Ten CIAT member countries that did not report any level of BEPS implementation are missing from this graph. Source: Author elaboration using information from the CIAT Data BEPS Monitoring database, accessed on June 2019

Mexico has considered, at least partially, some of the recommendations from 14 Actions (93%), all except for Action 4. Furthermore, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Costa Rica have considered the recommendations suggested in ten of the Actions (67%), while Ecuador and Uruguay are closest behind with seven Actions (46%).

5 Opportunities to Improve BEPS Suitability in Developing Countries

As is the case with most innovative approaches, at the start of the OECD/G20 BEPS Project, it was impossible to predict the globally felt ripple effects that would result from this initiative. It is irrefutable that the BEPS project has provided substantial support for governments and tax administrations in the creation of new policies, promoting capacity building, enhancing international cooperation initiatives, and others. Although these BEPS issues are important, a developing country must weigh their various competing demands against their limited resources. For example, the administration may want to prioritize items necessary to control taxpayers such as a taxpayer registry, information systems, collection tools, a transfer pricing regime, and risk analysis tools, among others.

Many developing countries had only general knowledge or limited experience in these topics at the moment when the BEPS Action Plan was being discussed; therefore, their needs may have been underrepresented in this first stage. Nevertheless, all of the topics have an important impact for developed and developing countries whose focus is now on attaining the capacity to achieve effective implementation. For less developed countries, the more prescriptive or “simpler” measures could generate the biggest impact. It will be interesting to see the developments that BEPS continues to inspire as it provides a guided path for advancements in the international tax arena.

The OECD is actively taking measures to overcome any representational bias as countries continue to learn and share their experiences in the groups and international forums provided by them. We expect that, as their experience continues to grow, developing countries will gradually have more influence on the BEPS initiative. Bearing this in mind, the following observations (especially relating to developing country needs) are presented for the evolution and further integration of the BEPS project.

-

A stronger focus on Action 11 and complementary concepts that aim to sustain and enhance BEPS in the developing world. For example, by promulgating opportunities for capacity building and technical assistance with the aim to increase domestic expertise.

-

Continual training and development programs for all levels (e.g., authorities, tax officials, and those in the judiciary) to improve the decision-making process and the effective implementation of legislations pertaining to BEPS.

-

Evaluation of alternatives for the BEPS recommendations that are not feasible in small or low-income developing countries. For example, offering a more simplified approach for administrations who find it difficult to justify spending limited resources on the application of complex measures and costly information regimes.

-

A stronger focus on tools that help to increase the effective collection of tax payable. This could allow developing countries to reduce the quantity of tax that has become uncollectible due to the statute of limitations period running out or the onset of a tax holiday.

-

Further analysis is necessary in relation to the impact of tax exonerations or holidays that may be found to cause tax base erosion. For example, it could be that Country A does not impose taxation on Company A because they are being taxed on that income in Country B (thereby Country A is avoiding juridical double taxation). However, if Country B then decides to provide a concession to Company A, this could be seen by Country A as an erosion of their tax base.

-

A stronger focus on integrated risk management processes would assist tax administrations to determine which taxpayers have a higher risk of BEPS and put the corresponding measures in place to pre-emptively desist such behavior.

-

More research in Actions 8–10 regarding the financial industries. This information could assist countries in furthering their understanding of the potential abuses that may arise from the use of inflated remuneration rates for financing services; financing entities; in-house banks; and potential permanent establishment thresholds when a lending entity has a certain share of the national debts.

Notes

- 1.

For comparison, the European Union countries with the least number of treaties signed, Croatia, Malta, and Slovenia, had an average of 67 treaties in 2018 (Hearson 2018).

- 2.

Access to the database of harmful cases, as well as the DIP tool, is only available to officials of CIAT member country tax administrations.

- 3.

References

CIATData. (2016). Double taxation agreements DTA’s. Retrieved from data base on transfer pricing rules and practices in Latin American and Caribbean countries: https://ciatorg.sharepoint.com/sites/cds/_layouts/15/Doc.aspx?sourcedoc=%7Bd447a547-6d55-4cc1-9603-f9659d7d6f31%7D&action=default&slrid=0e2a5a9f-5049-a000-f817-25bf91bf2707&originalPath=aHR0cHM6Ly9jaWF0b3JnLnNoYXJlcG9pbnQuY29tLzp4Oi9zL2Nkcy9FVWVsUjlSVmJjR

CIATData. (2018a, April). Anti-abuse rules. Retrieved from data base on transfer pricing rules and practices in Latin American and Caribbean countries: https://ciatorg.sharepoint.com/:x:/s/cds/Ec1sSRrEGLxIs5Cxi-Zii3gBh110QfB2Rlo_XTRiQuAHhA?e=pqo1Iu

CIATData. (2018b, April). General aspects. Retrieved from data base on transfer pricing rules and practices in Latin American and Caribbean countries: https://ciatorg.sharepoint.com/:x:/s/cds/ET2u9Wm_Y95DjpyRNCAKRu8BkbEeCAwcAcFOoyp5aouQxg?e=X23CpE

CIATData. (2019). Transfer pricing in Latin America and the Caribbean: A general overview based on CIATData. https://biblioteca.ciat.org/opac/book/5689

Hearson, M. (2018). The European Union’s tax treaties with developing countries. Brussels: GUE/NGL.

OECD. (2019). About—OECD BEPS. Retrieved from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/about/#:&:text=The%20OECD%2FG20%20Inclusive%20Framework,needed%20to%20tackle%20tax%20avoidance

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2015a). Aligning transfer pricing outcomes with value creation, actions 8–10—2015. Final reports. Paris: OECD. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264241244

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2015b). Countering harmful tax practices more effectively, taking into account transparency and substance, action 5—2015. Final report. Paris: OECD.

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2015c). Making dispute resolution mechanisms more effective, action 14—2015. Final report. Paris: OECD.

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2015d). Measuring and monitoring BEPS, action 11—2015. Final report. Paris: OECD. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264241343-en

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2015e). Preventing the granting of treaty benefits in inappropriate circumstances, action 6—2015. Final report. Paris: OECD.

OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project. (2015f). Transfer pricing documentation and country-by-country reporting, action 13—2015. Final report. Paris: OECD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Arias Esteban, I.G., Calderoni, A. (2021). The Suitability of BEPS in Developing Countries (Emphasis on Latin America and the Caribbean). In: Mosquera Valderrama, I.J., Lesage, D., Lips, W. (eds) Taxation, International Cooperation and the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda. United Nations University Series on Regionalism, vol 19. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64857-2_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64857-2_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-64856-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-64857-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)