Abstract

This chapter explores opportunities provided by strategic urban planning to mainstream climate risk considerations into the development decisions of city governments. It does so by describing the ways in which the climate-related information co-produced within the Future Resilience of African Cities and Lands (FRACTAL) project was integrated into the preparation of the Lusaka City Council Strategic Plan 2017–21. The chapter concludes by presenting four lessons emerging from the efforts at integrating climate information into the strategic planning process in Lusaka, Zambia: Lesson (1) Trust and relationships are key to sharing data and information needed to build a compelling case for managing climate risks; Lesson (2) Enable a variety of stakeholders to engage with climate information; Lesson (3) There needs to be an enabling legal, policy and financing framework; Lesson (4) Prepare to meet resistance; skilled intermediaries and city exchange visits help.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Reducing the climate risks facing cities is now firmly on the international policy agenda. The specifics of how to do so have to be worked out for each city, both in terms of assessing the climate risks and building contextually suitable responses into urban strategies, plans, budgets and programmes of work. This is no easy task. Cities around the world are grappling with the complexities of how to shift from piecemeal sectoral and project specific assessments and interventions to integrated city-wide, and ultimately city-regional, climate resilient urban development strategies and programmes (UN-Habitat 2015; Lomba-Fernández et al. 2019).

One vehicle for integrating climate considerations into high-level city planning is the strategic urban development plan many city governments produce and revise every four or five years. These are plans that set the priorities for directing public spending and the work of public officials and administrators tasked with delivering on the promises made by local and national politicians (Gore 2015). The process of developing, reviewing and revising such plans is a complex combination of politics, technical inputs and engagements with communities of residents and other key city stakeholder groups. There are growing efforts to ensure that these urban planning processes integrate the best available scientific climate information in order to align them with international and national climate agendas to deliver on low carbon and climate resilience targets (Giordano et al. 2020).

This chapter presents the case of developing the 2017–21 Strategic Plan for the city of Lusaka in Zambia. It explores how climate risks are characterised and prioritised in the plan (as compared with the 2010–15 Strategic Plan) and unpacks the processes by which various sources and types of climate information were integrated into the development of the Lusaka Strategic Plan, partly supported by efforts at co-exploring, co-producing and distilling relevant climate information within the Future Resilience of African Cities and Lands (FRACTAL ) project (Chap. 2). The chapter offers a set of reflections on how climate information and climate risk considerations, including a range of future projections, can be progressively brought into such strategic urban planning processes, across the technical, political and stakeholder engagement aspects, all of which are required to achieve real traction.

Climate Vulnerabilities in Lusaka

Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia, has an estimated population of 2.5 million. With an annual population growth rate of 4.8% (2000–18), it is projected to grow to 4.3 million by 2030 (UN DESA 2018). Climate variability and change is partly contributing to Lusaka’s rapid growth, as poor agricultural productivity in Zambia’s rural areas is leading to rising urban migration (Thurlow et al. 2012).

Lusaka is characterised by dramatic contrasts between modernist formal areas and impoverished informal parts of the city, which are home to over half of Lusaka’s population (Chitonge and Mfune 2015). However, climate impacts experienced in Lusaka cut across this formal-informal divide, in the form of water shortages, power outages, flooding and disease outbreaks, especially cholera triggered by flooding and poor sanitation.

Most of Lusaka’s electricity comes from hydropower generation. Roughly 40% of the water supplied to Lusaka by the Lusaka Water and Sewerage Company (LWSC ) is sourced from the Kafue River, some 50 kilometres from the city, and the remaining 60% is extracted from groundwater (Simukonda et al. 2018). However, the LWSC is only able to supply roughly 52% of the water demand from Lusaka’s rapidly growing population and industry. The remaining 48% is drawn directly from groundwater by private individuals and companies (FRACTAL 2019).

For those living and working in formal areas, periods of drought pose the risk of both severe water shortages and power outages. Low river flows result in the hydropower supply being interrupted, which in turn means that groundwater cannot be pumped from boreholes, and surface water from the Kafue River cannot be pumped to the city. Water and electricity shortages and rationing disrupt enterprise activity in Lusaka across multiple sectors, forcing businesses to reduce production, representing major economic losses (Mwila et al. 2017; Gannon et al. 2018). During prolonged dry periods, water kiosks (i.e. standpipes where water is sold to those without connections) and shallow wells run dry, forcing many in informal areas to travel far in search of alternative sources, often associated with very poor-quality water, in turn, presenting serious health risks (FRACTAL 2017).

Flooding is a regular occurrence across many parts of the city, due to a combination of intense rainfall, poor drainage and blockages in the drainage network from a lack of waste management (FRACTAL 2017). Many of Lusaka’s informal settlements experience floods on an annual basis, causing destruction of property and water borne diseases. Frequent cholera outbreaks are strongly associated with the quantity of rainfall. It is estimated that 60% of Lusaka’s urban areas have no adequate sanitation (FRACTAL 2017). Owing to lack of sewer lines, pit latrines are the most common sanitation facilities in informal settlements. In 2017, a cholera outbreak initially controlled by aggressive interventions, including hyper-chlorination and oral vaccine distribution, resurged after heavy rains followed by widespread water shortages, resulting in many deaths in Lusaka (Sinyange et al. 2018). In areas of poor sanitation, flooding acts as an outbreak trigger and the risk spreads across the city.

Climate projections for the Lusaka region suggest that all parts of Lusaka and surrounding regions will become warmer than they used to be, posing risks to health, agriculture and water supply (FRACTAL 2018). By the 2040s, temperatures may become up to 3 °C higher on average than current conditions, with extremely hot days and widespread heat waves becoming much more frequent (Ibid). Long-term rainfall trends for the Lusaka city region could entail drier rainfall seasons becoming much more common, with a tendency towards more prolonged drought conditions. However, Lusaka will continue to experience wet rainfall seasons with the associated risk of large-scale flooding. Some projections suggest that localised heavy rainfall events might become more frequent and intense (Jack et al. 2020).

Strategic Urban Planning as a Means of Mainstreaming Climate Action in Cities

Internationally, strategic urban planning emerged within the public sector in the 1970s and 1980s in the US and Europe, aimed at creating a framework to guide decisions and the allocation of resources based on the relative strengths of a city and emerging national and international opportunities and threats (Bryson and Roering 1987). Strategic urban planning takes a broader view than traditional master planning with its focus on land use regulation and infrastructure requirements. The use of strategic planning in cities is expanding with the hope of guiding not only the decisions across all functions and levels of city government, but also seeks to shape the mission, priorities and practices of other organisations operating in and shaping the city. Newer versions of strategic urban planning place emphasis on inclusion, participation and collaboration as a means of growing consensus and support for change towards future visions of the city (Albrechts et al. 2017).

Within African cities, the uptake of strategic urban planning has been recent and is not yet widespread. The rise of strategic urban planning marks a shift in urban poverty and development interventions from the microscale of locations (i.e. site specific slum upgrading projects) to policy interventions aimed at the city-wide scale, based on a recognition that the need is to connect people to jobs and services wherever they are located (Robinson 2008). There is a difficult balancing act undertaken in these exercises between pushing economic growth imperatives and basic service delivery imperatives, particularly in cities where high levels of unemployment persist and many residents live in hazardous, informal conditions of settlement.

Tackling climate change at the city scale is being added to the sustainability imperative within the design and development of strategic urban plans (UN-Habitat 2015). Adapting cities to changing climate conditions requires prioritising interventions across the spatial extent of the city region and the full range of climate risks and vulnerabilities. Several scholars argue that urban planning is a key field for tackling climate change in cities because it is a domain that draws in and effects many actors shaping the city space, it deals with numerous types of critical infrastructures and it is inherently forward looking (Parnell 2015; Lomba-Fernández et al. 2019). The challenge is that urban development decisions are inherently political in nature, as land and space have contested value and competing uses. Early evidence highlights the limitations and constraints of planning as a vehicle for city-wide climate adaptation, partly because planners within local authorities are constrained in the extent to which they can coordinate between sectors and have limited expertise in dealing with climate data and information (Carter et al. 2015).

De Satgé and Watson (2018) argue that planning in cities of the Global South operates in contexts characterised by conflicting rationalities between states and markets driven by the logic of modernisation, control and profit, and poorer communities driven by the logic of survival. Strategic planning is only as effective as the convening power and authority of the city government to regulate land use, direct investments and monitor activities to enforce compliance. In African cities, like Lusaka, this convening power and authority is weak, hence the very high levels of informality. Planning in the context of African cities is a discipline and a profession plagued by a poor reputation, limited legitimacy and severe capacity constraints, but planning cannot be bypassed if climate change is to be systematically addressed in cities (Parnell 2015). To explore this further, we now turn to the case of strategic urban planning in Lusaka to investigate what it reveals about the potential value and limitations for integrating climate risk information and furthering urban climate adaptation.

Integrating Climate Information into the Strategic Planning Process in Lusaka

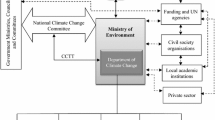

Lusaka still displays the colonial legacy of modernist planning inherited from the British town and country planning tradition; a functionalist, physical planning approach based on the zoning of physical space. This manifests as spatial segregation and the ongoing growth of informal settlements on the city’s periphery without adequate access to basic public services (Mulenga 2013). The Zambian government passed the Urban and Regional Planning Act in 2015 to reform the planning system towards being more inclusive and responsive to local development contexts. The Act requires all city planning authorities to produce strategic urban plans in the form of Integrated Development Plans. Prior to the passing of the Act, Lusaka City Council (LCC), with the support of various international donors, had already begun developing strategic plans with the first Strategic Plan for Lusaka City 1999–2004. This was replaced by the 2010–15 Strategic Plan. In 2016, this plan was reviewed and, in line with the decentralisation policy promoted by national government, a process of widespread community and stakeholder engagement was initiated to formulate a 2017–21 Strategic Plan for Lusaka. The review of the 2010–15 plan highlighted the importance of getting wide ownership of the Strategic Plan, from political and administrative leadership in local government, as well as public and private sector actors, to ensure implementation and measurable improvement in delivering public services to all communities.

The process of developing the new Strategic Plan coincided with the initiation of the FRACTAL programme, which had the aim of advancing the integration of scientific knowledge about regional climate patterns into city-regional decision-making to contribute towards resilient development pathways (see also http://www.fractal.org.za/lusaka/ and Chap. 2). The intersection of these two processes created opportunities for exploring climate-sensitive development issues facing Lusaka and how climate information might inform decisions being made about strategic priorities for local development. Table 7.1 provides a chronological account of the activities involved in integrating climate information into the development of Lusaka’s 2017–21 Strategic Plan.

The series of FRACTAL Learning Labs, City Dialogues, city exchange visits and training events described in Table 7.1 created engaging, collaborative spaces in which various stakeholders from government, civil society (including NGOs and community representatives) and the private sector came together with scientists to share knowledge and perspectives on urban development challenges and explore how some of these intersected with patterns of climate variability and change (Jack et al. 2020). A FRACTAL embedded researcher was employed for the duration of the project to work in two spaces, the University of Zambia (UNZA ) and the LCC, to ensure continued interaction between researchers and city officials. The embedded researcher played a key role in brokering the multi-stakeholder engagements and in sustaining interest and continued action on mainstreaming climate information in the Strategic Plan. Senior management staff and Councillors from LCC participated in city exchange visits to Durban and Windhoek to learn about how peer cities in the region are mainstreaming climate change in municipal policies and plans (Ndebele-Murisa et al. 2020). This was influential in mobilising high-level support for the integration of climate change concerns into Lusaka’s Strategic Plan.

Issues of water scarcity, groundwater exploitation, declining water quality linked to the lack of sanitation services and regular flooding became focal points for deliberation and knowledge co-production that fed into the Strategic Plan in several ways. Through the series of FRACTAL engagements, community representatives became confident in articulating the connections between the everyday challenges they were experiencing in their local area and broader processes of environmental and climate change playing out at the city-regional, national and global scales. Similarly, City Councillors deepened their understanding of the linkages between local livelihoods, health and safety concerns and environmental issues.

Through iterative FRACTAL-led efforts at unpacking and expanding a set of Climate Risk Narratives and developing thematic policy briefsFootnote 1 dealing with various water issues, community representatives, government decision-makers, planners and technical staff were arriving at new insights into the climate drivers and impacts of local development issues that they incorporated into their respective roles in contributing to the Strategic Plan. This is evidenced by the attention given to gathering information on weather and climate events, impacts and responses through community consultations in all 33 wards of Lusaka, and the inclusion of a climate change adaptation and mitigation strategy and program within the strategic priorities for the city, which was absent in the previous Strategic Plan. Further, the City formulated 12 local area plans for 12 wards to coordinate water security investments with a focus on informal settlements. These local area plans included explicit consideration of climate change implications for water security.

While the inclusion of climate adaptation and mitigation as a strategic priority marks an important step forward in Lusaka’s urban planning, the depth of integration and emphasis on managing climate risks should not be overestimated. Within the plan, there are signs of inconsistency and lingering confusion as to how identified climate risks translate into priority actions and relevant outcomes to be monitored. For example, the single indicator assigned to the climate change adaptation and mitigation programme is the number of trees planted. This does not tie into the water quality, quantity and equity concerns raised in relation to changing climate risks in the situational analysis section of the plan. But it marks the beginning of positioning climate change within the purview of urban development actors in Zambia, from the community level up to the Mayor. This work is continuing and being further deepened and expanded through the Lusaka Water Security Initiative (LuWSI), which as of 2019 is coordinated by the former FRACTAL embedded researcher, as well as the ongoing efforts of the wider FRACTAL network.

Lessons on Integrating Climate Risk into Urban Planning in African Cities

Based on the experience of working to integrate climate risk information into the Lusaka Strategic Plan 2017–21, four key lessons emerged that may be of use to planners, decision-makers and researchers in other cities grappling with how to mainstream climate into urban development strategies.

Lesson 1: Trust and Relationships Are Key to Sharing Data and Information Needed to Build a Compelling Case for Managing Climate Risks

Integrating climate risks and climate adaptation measures in urban planning requires having adequate data that show the costs of maintaining the status quo, as well as having data that show the benefits of planning for climate adaptation. Currently the data that exist are held by different agencies and departments in an uncoordinated and inaccessible manner, making integrated planning very difficult. The partnership between UNZA and LCC and the ways in which the FRACTAL Learning Labs and dialogues were convened and facilitated managed to overcome institutional barriers and brought relevant climate and development institutions together to share information and resources, and explore ways to build a climate resilient Lusaka. Contacts were exchanged among participants, formally and informally, and experiences shared that enabled increased collaboration on addressing climate change in Lusaka. Through iterative, highly collaborative engagements, stakeholders shared their institutionally held data and information, and this was key for the Strategic Plan formulation by the LCC. The FRACTAL and LuWSI network has continued to have high convening power among climate and development actors in Lusaka, building the relationships and trust needed to collaborate and share data. An information repository has been established with over 150 documents on water research, planning, water quality monitoring, land use and survey diagrams. Work is underway, convened by LuWSI, on a digital atlas and information management system that links different sources of information on climate, water, land use, planning and governance from key stakeholders in the water sector, with the aim of having various sources accessible in one place. However, there is still a long way to go to build a sustained culture of data sharing and collaboration among the local stakeholders.

Lesson 2: Enable a Variety of Stakeholders to Engage with Climate Information

Climate responses require an integrated and bottom up approach and therefore all responders from individuals to collective groups, institutions and other stakeholders need to be well informed and understand the linkages between impacts and climate drivers. Integration of climate risk and adaptation measures in urban planning should be discussed in locally relevant and meaningful terms, easily explained in local languages and in engaging formats, like graphics and stories, as was developed through the Climate Risk Narratives in FRACTAL. Climate risk is amplified by historical land use and planning inefficiencies and can easily be attributed to this. There is therefore a need to continuously disseminate information on climate conditions and potential impacts to various stakeholders and not only to decision-makers at City Council and Provincial government.

Lesson 3: There Needs to Be an Enabling Legal, Policy and Financing Framework

Integrating climate risk into urban planning is dependent on the type of legal and policy instruments available. For instance, the 2010–15 Strategic Plan was based on the Town and Country Planning Act that had very limited multi-stakeholder engagement. The 2017–21 Strategic Plan is guided by the decentralisation policy and the Urban and Regional Planning Act, which require that communities be represented and are involved in identifying risks and priorities, as well as part of the implementation of the plan. In the process of developing the Lusaka Strategic Plan, consultative meetings were held with communities, who proposed the types of solutions they would be able to undertake in response to the identified risks, including climate risks. Climate risk integration needs to align with existing national agendas, for example, the 7th National Development Plan and Zambia’s Vision 2030 in the case of Lusaka, as well as global and regional agreements, like the Durban Adaptation Charter. The need to meet certain criteria for funding also plays a key role in whether climate information is integrated or not.

Lesson 4: Prepare to Meet Resistance; Skilled Intermediaries and City Exchange Visits Help

There were some within the LCC, as well as in national government and other agencies, who felt that climate change and the use of climate information is not the mandate of the city government. There are many occasions when it is required to make a compelling and convincing case for why understanding and managing climate risks are integral to achieving the service delivery and urban development goals of the city government. Skilled intermediaries are needed to bring relevant climate research into the purview of planners and managers. These intermediaries not only need to be adequately knowledgeable but should have influence and be able to integrate alternative perspectives and new ideas into high-level decision-making spaces. They need to be able to navigate across the various layers of consultation and decision-making spaces with ease. Appointing someone with both a solid academic background and considerable experience working in government as the FRACTAL embedded researcher to work as an intermediary between the university and the City Council, proved central to the success of mainstreaming climate risks into the Lusaka strategic planning process. As was the diplomacy and strategic vision of the FRACTAL project leader in Lusaka.

It is necessary to get key high-level decision-makers on board and bought into the climate agenda in order to support the process and overcome barriers and stumbling blocks. The FRACTAL city exchange visits that saw senior managers and Councillors visiting other cities in the region that are further ahead in advancing a city climate agenda proved impactful in building high-level support. Ultimately, climate risks and measures to manage them must be identified through a clear and mutually agreed process, with the appropriate figureheads endorsing the approach as well as the resulting priorities, otherwise it will not translate into action.

In conclusion, these lessons will need to be taken forward within Lusaka, where the next challenge is to translate the Strategic Plan into an Integrated Development Plan that provides spatial specificity as to how the ambitions and priorities laid out in the Strategic Plan will be implemented. In parallel, strategies for addressing climate and water risks in high risk settlements are being pursued through the Lusaka Water Security Action and Investment Plan.

Notes

- 1.

The Climate Risk Narratives and the set of policy briefs can be accessed via: http://www.fractal.org.za/lusaka/

References

Albrechts, L., Balducci, A., & Hillier, J. (Eds.). (2017). Situated practices of strategic planning: An international perspective. London: Routledge.

Bryson, J. M., & Roering, W. D. (1987). Applying private-sector strategic planning in the public sector. Journal of the American Planning Association, 53(1), 9–22.

Carter, J. G., Cavan, G., Connelly, A., Guy, S., Handley, J., & Kazmierczak, A. (2015). Climate change and the city: Building capacity for urban adaptation. Progress in Planning, 95, 1–66.

Chitonge, H., & Mfune, O. (2015). The urban land question in Africa: The case of urban land conflicts in the city of Lusaka, 100 years after its founding. Habitat International, 48, 209–218.

De Satgé, R., & Watson, V. (2018). Urban planning in the global south: Conflicting rationalities in contested urban space. New York: Springer.

FRACTAL. (2017). Report: Lusaka learning lab 2. Retrieved from http://www.fractal.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Lusaka-Learning-Lab-2-July-2017_final-report_small.pdf

FRACTAL. (2018). Climate risk narratives and climate information for Lusaka: Lusaka climate training Session 7. Retrieved from http://www.fractal.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Climate-Training-Session-7-Lusaka.pdf

FRACTAL. (2019). Lusaka policy brief: Lusaka city faced with severe consequences of declining groundwater levels. Retrieved from http://www.fractal.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Policy-Brief-Lusaka-Groundwater-Levels-web-version.pdf

Gannon, K., Conway, D., Pardoe, J., Ndiyoi, M., Batisani, N., Odada, E., Olago, D., Opere, A., Kgosietsile, S., Nyambe, M., Omukuti, J., & Siderius, C. (2018). Business experience of floods and drought-related water and electricity supply disruption in three cities in sub-Saharan Africa during the 2015/2016 El Niño. Global Sustainability, 1, E14.

Giordano, R., Pilli-Sihvola, K., Pluchinotta, I., Matarrese, R., & Perrels, A. (2020). Urban adaptation to climate change: Climate services for supporting collaborative planning. Climate Services, 17, 100100.

Gore, C. (2015). Climate Change Adaptation and African cities: Understanding the impact of government and governance on future action. In C. Johnson, N. Toly, & H. Schroeder (Eds.), The urban climate challenge (pp. 215–234). London: Routledge.

Jack, C. D., Jones, R., Burgin, L., & Daron, J. (2020). Climate risk narratives: An iterative reflective process for co-producing and integrating climate knowledge. Climate Risk Management, 29, 100239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2020.100239.

Lomba-Fernández, C., Hernantes, J., & Labaka, L. (2019). Guide for climate-resilient cities: An urban critical infrastructures approach. Sustainability, 11, 4727.

Mulenga, C. L. (2013). Urban slums report: The case of Lusaka, Zambia. Retrieved from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/dpu-projects/Global_Report/pdfs/Lusaka.pdf

Mwila, A., Sinyenga, G., Buumba, S., Muyangwa, R., Mukelabai, N., Sikwanda, C., Chimbaka, B., Banda, G., Nkowani, C., & Bwalya, B. K. (2017). Impact of load shedding on small scale enterprises (Working Paper 1). Zambia: Energy Regulation Board.

Ndebele-Murisa, M. R., Mubaya, C. P., Pretorius, L., Mamombe, R., Iipinge, K., Nchito, W., Mfune, J. K., Siame, G., & Mwalukanga, B. (2020). City to city learning and knowledge exchange for climate resilience in Southern Africa. PLoS One, 15, e0227915.

Parnell, S. (2015). Fostering transformative climate adaptation and mitigation in the African City: Opportunities and constraints of urban planning. In S. Pauleit, A. Coly, S. Fohlmeister, P. Gasparini, G. Jørgensen, S. Kabisch, W. J. Kombe, S. Lindley, I. Simonis, & K. Yeshitela (Eds.), Urban vulnerability and climate change in Africa: A multidisciplinary approach (pp. 349–367). New York: Springer.

Robinson, J. (2008). Developing ordinary cities: City visioning processes in Durban and Johannesburg. Environment and Planning A, 40, 74–87.

Simukonda, K., Farmani, R., & Butler, D. (2018). Causes of intermittent water supply in Lusaka City, Zambia. Water Practice & Technology, 13(2), 335–345.

Sinyange, N., et al. (2018). Cholera epidemic – Lusaka, Zambia, October 2017–May 2018. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 67(19), 556–559. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6719a5

Thurlow, J., Zhu, T., & Diao, X. (2012). Current climate variability and future climate change: Estimated growth and poverty impacts for Zambia. Review of Development Economics, 16(3), 394–411.

UN-Habitat. (2015). Integrating climate change into city development strategies (CDS). Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Retrieved from https://unhabitat.org/integrating-climate-change-into-city-development-strategies

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), Population Division. (2018). The world’s cities in 2018: Data booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/417). Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/events/citiesday/assets/pdf/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Taylor, A., Siame, G., Mwalukanga, B. (2021). Integrating Climate Risks into Strategic Urban Planning in Lusaka, Zambia. In: Conway, D., Vincent, K. (eds) Climate Risk in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61160-6_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61160-6_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-61159-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-61160-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)